Reconsidering Pay Dispersion's Effect on the Performance of Interdependent Work

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:383.55 KB

- 文档页数:57

In todays society,gender discrimination remains a pervasive issue despite significant advancements in gender equality.This essay will explore the various forms of gender discrimination,its impact on individuals and society,and the steps that can be taken to combat this problem.Forms of Gender Discrimination1.Workplace Discrimination:Women are often paid less than men for the same work,a phenomenon known as the gender pay gap.Additionally,they may face barriers to promotion and leadership positions due to unconscious bias or overt prejudice.cational Bias:Girls may be discouraged from pursuing careers in STEM Science, Technology,Engineering,and Mathematics fields due to societal expectations and stereotypes that these are maledominated areas.3.Social Stereotypes:Traditional gender roles can limit the activities and interests of both boys and girls,with boys often being discouraged from expressing emotions or pursuing careers in caregiving,while girls are steered away from activities seen as aggressive or competitive.4.Media Representation:The media often perpetuates gender stereotypes through the portrayal of women as submissive or overly sexualized,and men as aggressive or unemotional.Impact of Gender Discrimination1.Mental Health:Gender discrimination can lead to feelings of inadequacy,low selfesteem,and depression among those affected.2.Economic Disparity:The gender pay gap contributes to economic inequality,affecting not only the individual but also the family unit and the broader economy.3.Social Inequality:Gender discrimination reinforces power imbalances and can lead toa lack of representation in decisionmaking roles,perpetuating a cycle of inequality.cational Disadvantages:When girls are discouraged from pursuing certain fields of study,it limits their future career opportunities and contributes to a skills gap in those industries.Combating Gender Discrimination1.Legislation:Implementing and enforcing laws that prohibit gender discrimination in the workplace and education can help create a more level playing field.cation and Awareness:Raising awareness about gender discrimination and educating people about its effects can change attitudes and behaviors.3.Promoting Equality in the Workplace:Companies can adopt policies that ensure equal pay and opportunities for all employees,regardless of gender.4.Challenging Stereotypes:Encouraging media and advertising to portray a more diverse and realistic representation of both genders can help to break down societal expectations.5.Support Networks:Creating support networks for those affected by gender discrimination can provide a platform for sharing experiences and advocating for change. In conclusion,gender discrimination is a complex issue that affects individuals and society as a whole.By recognizing and addressing its various forms,we can work towards a more equitable world where everyone has the opportunity to reach their full potential,regardless of their gender.。

APPENDIX DINTERNAL CONTROLAn important responsibility of management is the establishment and maintenance of the internal control structure. To provide reasonable assurance that a facility's objectives will be achieved, the internal control structure should be under ongoing supervision by management to determine that it is operating as intended and that it is modified as appropriate for changes in conditions.Formal DefinitionInternal control comprises the plan of an organization and all coordinate methods and measures adopted within a business to safeguard its assets, check the accuracy and reliabilityof its accounting data, promote operational efficiency, and encourage adherence to prescribed managerial policies.Characteristics of Internal ControlThe following are general characteristics of a satisfactory system of internal control:- A plan of organization which provides appropriate segregation of duties.-Personnel of a quality commensurate with responsibilities.-Sound practices to be followed in performance of duties and functions of each of the organizational departments.- A system of authorization and recordation procedures adequate to provide reasonable accounting control over assets, liabilities, revenues, and expenses.The above summary emphasizes both the organizational structure and the systems of procedures to be used in the organization. Within this framework, internal control can be divided into three types of controls: the control environment, the accounting system, and control procedures.Control EnvironmentThe control environment represents the collective effect of various factors on establishing, enhancing, or mitigating the effectiveness of specific policies and procedures. Such factors include the following:-Management's philosophy and operating style-The facility's organizational structure-The functioning of the board of directors and its committees, particularly the audit committeeAPPENDIX D-Methods of assigning authority and responsibility-Management's control methods for monitoring and following up on performance, including internal auditing-Personnel policies and practices-Various external influences that affect a facility's operations and practices, such as examinations by bank regulatory agenciesThe control environment reflects the overall attitude, awareness, and actions of the board of directors, management, owners, and others concerning the importance of control and its emphasis in the entity.Accounting SystemThe accounting systems consist of the methods and records established to identify, assemble, analyze, classify, record, and report a facility's transactions and to maintain accountability for the related assets and liabilities. An effective accounting system gives appropriate consideration to establishing methods and records that will---Identify and record all valid transactions.-Describe on a timely basis the transactions in sufficient detail to permit proper classification of transactions for financial reporting.-Measure the value of transactions in a manner that permits recording their proper monetary value in the financial statements.-Determine the time period in which transactions occurred to permit recording of transactions in the proper accounting period.-Present properly the transactions and related disclosures in the financialstatements.Control ProceduresControl procedures are those policies and procedures in addition to the control environment and accounting system that management has established to provide reasonable assurance that specific facility objectives will be achieved. Control procedures have variousAPPENDIX Dobjectives and are applied at various organizational and data processing levels. They may also be integrated into specific components of the control environment and the accounting system. Generally, they may be categorized as procedures that pertain to---Proper authorization of transactions and activities.-Segregation of duties that reduces the opportunities to allow any person to be in a position to both perpetrate and conceal errors or irregularities in the normal courseof his duties. Segregation of duties includes assigning different people theresponsibilities of authorizing transactions, recording transactions, and maintainingcustody of assets.-Design and use of adequate documents and records to help ensure the proper recording of transactions and events, such as monitoring the use of prenumberedshipping documents.-Adequate safeguards over access to and use of assets and records, such as secured facilities and authorization for access to computer programs and data files.-Independent checks on performance and proper valuation of recorded amounts, such as clerical checks, reconciliations, comparison of assets with recordedaccountability, computer-programmed controls, management review of reportsthat summarize the detail of account balances (for example, an aged trail balance ofaccounts receivable), and user review of computer-generated reports.Revenue and Accounts ReceivableProper accounting for revenues and the related accounts receivable is a matter of considerable importance since no long-term care facility can survive for long without adequate revenues. To assure adequate controls in this area the administrator should ensure that: -There are effective controls that all charges are billed and properly recorded on the accrual basis of accounting and properly classified by type of service rendered.-Revenues are based on pre-numbered charge slips, daily census and/or other effective controls.-Controls are in effect to assure the accuracy and completeness of medical records information.APPENDIX D-Rates are approved by management and comply with regulatory requirements, if applicable.-Patient billings are maintained on a current basis.-Units of service and statistics that affect revenue determination are properly recorded.-Accounts receivable detailed records are complete and reconciled to the control accounts.-Accounts receivables are reported at net realizable value.-To the extent practicable, there is an adequate segregation of duties among billings, accounts receivable, and cash functions.Segregation of duties is fundamental to good control procedures. Conflicting duties for control procedures are those that place any person in a position to perpetuate and to conceal errors or irregularities in the normal course of his or her work. Different people should be assigned the responsibility of authorizing transactions, recording transactions, and maintaining custody of assets. While complete absence of conflicting duties is ideal, it is not always attainable with the limited staff common in smaller long-term care facilities. In the event various duties cannot be adequately segregated, the administrator, or his or her designated representative without conflicting duties, should perform alternative reviews. Such alternative procedures could include a careful review of the monthly aged detail accounts receivable trial balance for unusual items, personal follow up on delinquent account balances, personal review of the reasons for and approval of bad debts, write-offs and other noncash credits to accounts receivable, test posting of credits to patient accounts from revenue and cash receipt journals and a review of the reconciliation of patient census records, charge tickets, and vendor invoices for contract services to the revenue journal.Cash ReceiptsCash is a necessity in business operations. Due to the large number of cash transactions and the susceptibility to misappropriation, the controls placed over the handling of cash play an important role in any system of internal control. To assure adequate controls over cash receipts the administrator should require that:-Receipts are deposited daily and intact.-Currency receipts are effectively controlled by registers, or if impractical, cash receipt slips. Such slips should be prenumbered and accounted for on a periodicbasis.-All checks received should promptly be endorsed for "deposit only" to the appropriate account.APPENDIX D-To the extent practicable, cash receiving is centralized to a person without authority to sign checks and not involved in reconciling bank accounts.-The administrator initiate bad debt write-offs or other noncash credits to accounts receivable, and submit write-offs to management for approval.-Bank reconciliations are performed on a monthly basis and approved bymanagement.If an adequate segregation of duties cannot be accomplished due to limited staff, the administrator can perform various reviews to compensate for the lack of segregation. The administrator can review the timeliness of bank deposits to assure cash is directly deposited for the institution's use. The administrator can reconcile bank accounts personally or carefully review the reconciliation and test cash receipts posting to patient accounts to assure proper application. Purchasing and Accounts PayableThe purchasing function creates obligations and the accounts payable function of a facility records the liabilities of the facility. To assure adequate controls the administrator should require: -Effective use and control of purchase orders by using prenumbered, sequential forms.-Procedures to assure purchases at competitive prices.-Effective review of vendor's invoices, pricing and extension and matching invoices with purchase orders and receiving reports.-To the extent practicable, there is adequate segregation of duties withinpurchasing, accounts payable and receiving functions.For a facility without the desired segregation of duties, the administrator should review all invoices of large dollar amounts and others on a test basis. It is also good policy to require signed receiving documents from various departments within the facility, acknowledging receipts of significant purchases of goods such as medical supplies, drugs and medications, and food.APPENDIX DCash DisbursementsThe need to control cash disbursements is just as great as the need to control receipts. To assure adequate controls over cash disbursements the administrator should require:-All disbursements of a material amount are to be made by check (minor cash disbursements may be made from a petty cash fund maintained on an imprestbasis).-Checks are to be prenumbered and serially controlled.-Checks are to be signed only if accompanied by supporting documents.Supporting documents should include evidence of receipt and approval.-Control totals of amounts should be maintained over the check at each processing point.-Perforating, stamping, or other procedures to be used to prevent reuse ofvouchers, particularly petty cash slips or other cash vouchers and voided checks.- A policy prohibiting checks being signed in blank.-Preparation of regular monthly bank reconciliations by an individual independent of all cash related functions.-The employees responsible for accounting records should be prohibited from having the authority to sign checks.-Different persons should prepare checks, reconcile bank accounts and have access to cash receipts.The administrator should perform alternative reviews when segregation of duties is not practical. The administrator should sign checks only with satisfactory documentation that the disbursement is proper. The administrator should also see that checks are mailed directly from his or her office by the check signer without returning to the person who maintains the cash disbursements and accounts payable records. Standard policies should prohibit preparation of checks made payable to "cash" and require periodic reconciliation of the petty cash balance.APPENDIX DPayrollSalaries and wages represent a major portion of a long-term care facility's operating expenses. Governmental agencies require the facility to maintain adequate payroll and personnel records. A sound system of internal control is necessary to produce these records accurately. The following procedures help to provide this control:-Written authorizations are on file for all employees; covering rates of pay, withholdings and deductions.-Accumulation of hours worked by department is based on mechanical or other independent sources.-Accounting distribution of payroll costs is on the basis of approved documentation prepared by the administrator or his or her authorized representative.-Control totals of amounts should be maintained at each processing point.-To the extent practicable, there is adequate segregation of duties between the maintenance of personnel files, the preparation of checks and journals, and thedistribution of payroll checks.To compensate for the lack of segregation of duties the administrator can maintain control of all blank payroll checks, review time cards prior to signing checks, reconcile the payroll bank account, review the payroll journal and personally authorize pay rate adjustments and payroll additions and deletions.InventoriesThe primary purpose of control of inventory is to physically safeguard the assets. This can effectively be done by the following procedures:-Centralized, orderly storage with limited and controlled access to supplies.-Assignment of responsible persons to receive, store, issue and control inventory.-Periodic physical counts of the inventory; at least annually, by persons other than the storekeepers.-Use of a planned and orderly system for purchase and issue of supplies designed to control optimum quantities of supplies on hand.APPENDIX D-Periodic review of inventory records and other data to determine if quantities on hand are excessive or if any supplies are obsolete or slow-moving.Property, plant, and equipmentInternal control over property, plant, and equipment is designed to safeguard the assets and provide accurate accounting records for management control, depreciation and salvage value calculations, and to make correct entries for retirements and disposals. The following guidelines will be helpful in establishing this control:-There is an effective system of authorization and approval with respect to capital expenditures.-Capitalization and depreciation policies are defined in writing.-There are detailed records of individual asset items which are balanced periodically with general ledger control accounts.-There are effective procedures regarding the authorization and accounting for disposals.-Donated property and equipment is reported at its fair market value on the date of donation.The administrator may wish to attach an identifying tag to each piece of departmental equipment to track the equipment locations.Internal Control ChecklistThe following checklist has been developed to allow administrators to review their existing system of internal control in a systematic manner to determine areas where improvement of procedures may strengthen controls. In considering changes in accounting controls, the administrator must evaluate the cost-benefit relationship of varying levels of control procedures and select the procedures which are appropriate in the circumstances. Also, it should be recognized that no checklist can contain all procedures that may be appropriate in all circumstances and, accordingly, the administrator should not limit his or her consideration to those items contained in the checklist. Section I of the checklist discusses accounting controls and Section II deals with general controls.CHECKLIST FOR REVIEW OF INTERNAL CONTROLSFOR LONG-TERM CARE FACILITIESAPPENDIX DI.ACCOUNTING CONTROLSRevenue and accounts receivableA..Patient revenue:1.Are services rendered only on order of physicians?2.Do procedures ensure that revenue is accrued as services are performed?3.Are all departmental personnel responsible for initiating charge slipsproperly instructed and currently advised of policy changes?4.Are there effective controls that all charge slips prepared are received andrecorded by the person recording revenue?5.Are all patient charges supported by proper authorizations for services?6.Are voided charge slips approved and retained and appropriately canceled?7.Is there a periodic review and comparison, on a test basis, of patient'smedical records to charges recorded? Is the extent of this procedureadequate for the circumstances?8.How are prices determined? Are prices which are not based on standardlists approved by a responsible official?9.Who prices and extends charge slips?10.Are prices and extensions checked by a second person? To what extent?11.Do controls ensure that deductions from revenue are recorded in theproper period and are properly classified and authorized?12.Is the authority to approve deductions from revenue separate from thecashiering and billing functions?CHECKLIST FOR REVIEW OF INTERNAL CONTROLSFOR LONG-TERM CARE FACILITIESAPPENDIX DB.Billing--consider:1.Are statements rendered at least monthly or at time of discharge or within afew days thereafter?2.Are statements rendered promptly with an estimate of the self-pay balanceprior to receipt of insurance payments?3.Are statements mailed monthly to all patients having account balances?4.Who is responsible for billings? Are billings current?C.Credit:1.Are preadmission deposits requested or payment terms arranged inadvance, or at least at time of admission?2.Does the admission procedure provide for obtaining necessary insuranceand other information for billing and credit use?3.Is there a current and effective review and follow-up on all accounts?4.Is reasonable use made of outside collection agencies?5.If nonprofit, are IRS and Hill-Burton charity requirements met?D.Accounts receivable--consider:1.Are accounts receivable ledgers balanced with the ledger monthly?2.Are aged listings prepared with sufficient frequency to meet the institution'sneeds? How often?3.Is the person posting accounts receivable properly instructed as to requiredapproval for noncash credits?4.Is a record maintained of accounts written off as uncollectible? Are thesefollowed up for recoveries and is there proper control over suchrecoveries?CHECKLIST FOR REVIEW OF INTERNAL CONTROLSFOR LONG-TERM CARE FACILITIESAPPENDIX DE.Patient statistics--consider:1.Is there a logical, organized system for accumulating patient statistics?2.Is the accumulation of patient statistics done simultaneously, or at leastcoordinated, with the accumulation and recording of revenue? If not, isthere a review and comparison made between the two?3.Are there effective controls, such as review and tests of accumulations by asecond person, to ensure the accuracy of statistics?F.Other revenue (operating and nonoperating):Are there adequate controls over the receipt of other (operating and nonoperating) revenues such as:a.Sales of, or income from securities, notes, savings?b.Rental income?c.Sale of surplus equipment, supplies, etc.?d.Cash sales of drugs, medical supplies, etc.?e.Vending machines?f.Sale of medical records?g.Periodic purchase rebates?h.Gifts, donations, grants, etc.?i.Revenue from educational programs?G.Cash Receipts:1.Are all receipts recorded promptly and deposited intact daily (or at otherfrequent, regular intervals)?CHECKLIST FOR REVIEW OF INTERNAL CONTROLSFOR LONG-TERM CARE FACILITIESAPPENDIX D2.Does the cashier prepare duplicate deposit tickets so that one can be signedby the bank and returned for comparison to the cash receipts record?3.Is the person receiving cash without authority to sign checks, withoutaccess to accounting records other than cash receipts (particularly patientledgers) and without access to or custody of negotiable assets?4.Is all cash which should be received, recorded as a receivable prior toreceipt, to the extent practicable?5.Are receipts in currency properly controlled, (i.e., through cash registers,vending machines, prenumbered locked receipt forms, etc.), and are thereadings on such registers, machines or locked receipts used as an effectivecontrol over cash which should be recorded and deposited?H.Purchasing and Accounts Payable:1.Are all purchases of material or services made by authorized personnel andare all commitments covered by purchase orders?2.Are competitive prices established?3.Who signs purchase orders and are there any limits above which additionalapproval is necessary?4.Is there adequate control over and accounting for purchases orders, (i.e.,pre-numbering, purchase order log, consecutive number assignment, etc.)?5.Does the accounting department match invoices with purchase orders andreceiving reports comparing quantities, prices, terms, etc., and are thesedocuments retained together as a voucher package?6.Are receiving reports attached to invoices?7.Are unmatched invoices, purchase orders or receiving reports which remainopen for some time investigated periodically?8.Are extensions on invoices and freight charges checked by the accountingdepartment?CHECKLIST FOR REVIEW OF INTERNAL CONTROLSFOR LONG-TERM CARE FACILITIESAPPENDIX D9.Is the account distribution assigned by a second person?10.Is there an auditor of disbursements who reviews each voucher to see thatproper procedures have been followed?11.Is the total of unpaid voucher items agreed to the related general ledgeraccount each month?12.Are debit balances followed up for prompt application against otherinvoices or for cash reimbursement?13.Is there a satisfactory procedure for cross-referencing checks to vouchers?14.Are the people working with accounts payable different from thoseworking on cash receipts and mailing of checks?15.Are accrual accounts maintained for all major items which are not paidpromptly or regularly?I.Cash Disbursements:1.Are checks controlled and accounted for with proper safeguards in effectover unused, returned, and voided checks?2.Is the drawing of checks to the order of "cash" or "bearer" prohibited?3.Do invoices, purchase orders and receiving reports accompany checks forthe check signer's review?4.Are perforating, stamping or other procedures effectively used to preventreuse of vouchers, particularly petty cash slips or other cash vouchers?5.Are check signers responsible officials or employees in all cases?6.Are two signatures required on checks (not essential in all cases whereother adequate controls are present)?7.Is there adequate control over signature plates, if used?CHECKLIST FOR REVIEW OF INTERNAL CONTROLSFOR LONG-TERM CARE FACILITIESAPPENDIX D8.Are checks mailed without allowing them to return to the person whoprepared the check or initiated the voucher (or check request)?9.Are all petty cash disbursements required to be reimbursed by check withadequate scrutiny at the time of reimbursement?10.Are petty cash slips required and written in ink to prevent alteration?11.Is a maximum amount, reasonable in the circumstances, fixed for paymentsin cash?12.Are all bank accounts required to be authorized by the Board of Directors,Governing Board or owners?13.Are bank accounts reconciled monthly by someone who does not preparechecks or have access to cash?14.Are the reconciliation procedures adequate?J.Payroll:1.Is there a personnel function separate from the payroll function whichmaintains complete personnel records including rate data?2.Are the procedures adequate to assure correct time reporting?3.Are labor distribution records independently computed and tabulated in amanner to provide a check of aggregate pay?4.Are accounting distributions for salaries and wages carefully made,checked by a second person, and approved by an accounting official?5.Are payroll computations independently checked?6.Does the person reconciling the payroll bank account examine paid checksfor dates, payees, cancellations and endorsements and does he or sheaccount for numerical sequence?7.Is there adequate control over unclaimed wages or old outstanding payrollchecks to prevent diversion?CHECKLIST FOR REVIEW OF INTERNAL CONTROLSFOR LONG-TERM CARE FACILITIESAPPENDIX D8.Are pay rate adjustments and personnel additions and deletionsappropriately authorized in writing?9.Are checks distributed by someone not involved in the authorization orpreparation of payroll information?K.Inventories:1.Are inventories stored in a systematic manner?2.Are they under the direct control of persons who are held responsible forquantities on hand?3.Are there controls over access to storage areas for persons without suchresponsibility?4.Is there a planned system for purchase and issue of supplies?5.Is there a regular review of inventory records and other data to determinequantities on hand which are slow-moving, excessive or obsolete?L.Property, Plant, and Equipment:1.Are administrative authorizations and approvals required to originate anexpenditure which will be chargeable to fixed assets and in this respect arepolicies adequate regarding minimum amounts capitalized, minimumamounts requiring approval at various levels, distinction between repairs,replacements, renewals, betterments, treatment of freight and othercollateral costs, etc.?2.Are work orders established to assist in the proper accounting for items tobe capitalized?3.Are supplemental authorizations required for excess expenditures?4.Are there detailed plant records showing the asset values for the individualitems of plant and equipment and dates placed in service?5.Are the detailed records integrated with the financial accounting system?CHECKLIST FOR REVIEW OF INTERNAL CONTROLSFOR LONG-TERM CARE FACILITIESAPPENDIX D6.Is the accuracy of these records independently checked by periodic,physical inspection?7.Are records kept of equipment on hand but not carried in the generalbooks, such as fully depreciated equipment still in use, obsolete equipmentand idle equipment?8.Is written authority required for fixed asset dispositions?9.Does the accounting department receive copies of such authorizations?10.Is the estimated salvage value shown on all retirement orders and followedup for subsequent cash receipts?11.Are periodic reports submitted showing obsolete equipment, equipmentneeding repairs, or equipment not in service for any other reason?12.Are procedures in effect to prevent depreciation of fully depreciated assets?13.Is gain or loss computed on all fixed asset dispositions?II.GENERAL CONTROLSanization:1.Is there an organization chart?2.Is the responsibility clear for the major revenue and expense centers?B.Planning:1.Is there an annual operating budget?2.How are rates established? Are rates based upon full costs?3.Are cash forecasts prepared routinely, if so how often and for what timeperiod?CHECKLIST FOR REVIEW OF INTERNAL CONTROLSFOR LONG-TERM CARE FACILITIESAPPENDIX D4.Is capital budgeting used? If yes, is it prepared for a period of at least threeyears?C Financial statements:1.Are complete statements prepared monthly?2.Are the statements constructed to correlate with responsibilities and aredepartmental reports prepared?3.Can the statements be directly prepared from the general ledger chart ofaccounts?4.Do they highlight important matters and show trends? Are graphs used?5.Are actual results compared to the budget?6.Are variances from budget analyzed and are they discussed withdepartmental heads?7.If actual results are compared to budget, to what are they compared?8.Are the interim financial statements prepared in a timely manner?9.Are the statements reasonably accurate (credibility)?10.Are year-end adjustments significant? Explain.11.Is there a need for information between statement dates?D.Data processing:1.Are the batch and edit controls generally adequate?2.Is there a good balance between electronic data processing and manualsystems?3.Are the computer programs adequately documented?4.Is file protection adequate?。

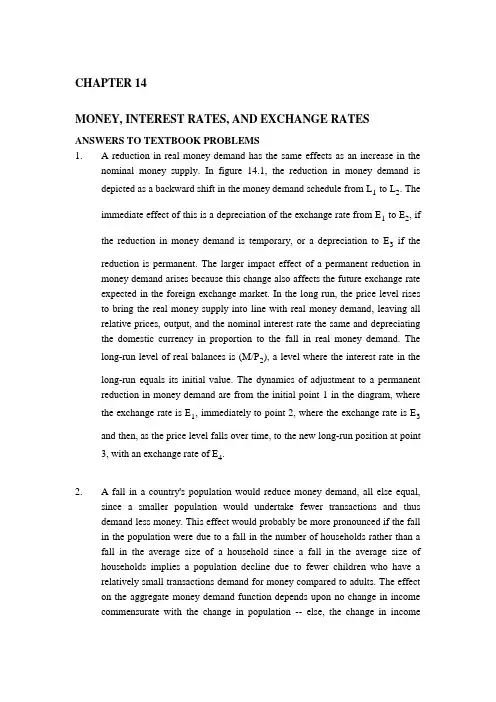

CHAPTER 14MONEY, INTEREST RATES, AND EXCHANGE RATESANSWERS TO TEXTBOOK PROBLEMS1. A reduction in real money demand has the same effects as an increase in thenominal money supply. In figure 14.1, the reduction in money demand isdepicted as a backward shift in the money demand schedule from L1 to L2. The immediate effect of this is a depreciation of the exchange rate from E1 to E2, if the reduction in money demand is temporary, or a depreciation to E3if thereduction is permanent. The larger impact effect of a permanent reduction in money demand arises because this change also affects the future exchange rate expected in the foreign exchange market. In the long run, the price level rises to bring the real money supply into line with real money demand, leaving all relative prices, output, and the nominal interest rate the same and depreciating the domestic currency in proportion to the fall in real money demand. The long-run level of real balances is (M/P2), a level where the interest rate in thelong-run equals its initial value. The dynamics of adjustment to a permanent reduction in money demand are from the initial point 1 in the diagram, where the exchange rate is E1, immediately to point 2, where the exchange rate is E3and then, as the price level falls over time, to the new long-run position at point 3, with an exchange rate of E4.2. A fall in a country's population would reduce money demand, all else equal,since a smaller population would undertake fewer transactions and thus demand less money. This effect would probably be more pronounced if the fall in the population were due to a fall in the number of households rather than a fall in the average size of a household since a fall in the average size of households implies a population decline due to fewer children who have a relatively small transactions demand for money compared to adults. The effect on the aggregate money demand function depends upon no change in income commensurate with the change in population -- else, the change in incomewould serve as a proxy for the change in population with no effect on the aggregate money demand function.R(M/P E 1E 4E 2E 3E(M/PFigure 14-13. Equation 14-4 is M s /P = L(R,Y). The velocity of money, V = Y/(M/P). Thus,when there is equilibrium in the money market such that money demand equals money supply, V = Y/L(R,Y). When R increases, L(R,Y) falls and thus velocity rises. When Y increases, L(R,Y) rises by a smaller amount (since the elasticity of aggregate money demand with respect to real output is less than one) and the fraction Y/L(R,Y) rises. Thus, velocity rises with either an increase in the interest rate or an increase in income. Since an increase in interest rates as well as an increase in income cause the exchange rate to appreciate, an increase in velocity is associated with an appreciation of the exchange rate.4. An increase in domestic real GNP increases the demand for money at anynominal interest rate. This is reflected in figure 14-2 as an outward shift in the money demand function from L 1 to L 2. The effect of this is to raise domestic interest rates from R 1 to R 2 and to cause an appreciation of the domestic currency from E 1 to E 2.5. Just as money simplifies economic calculations within a country, use of avehicle currency for international transactions reduces calculation costs. More importantly, the more currencies used in trade, the closer the trade becomes to barter, since someone who receives payment in a currency she does not need must then sell it for a currency she needs. This process is much less costly when there is a ready market in which any nonvehicle currency can be traded against the vehicle currency, which then fulfills the role of a generally accepted medium of exchange.REE 1E 2Figure 14-26. Currency reforms are often instituted in conjunction with other policies whichattempt to bring down the rate of inflation. There may be a psychological effect of introducing a new currency at the moment of an economic policy regime change, an effect that allows governments to begin with a "clean slate" and makes people reconsider their expectations concerning inflation. Experience shows, however, that such psychological effects cannot make a stabilization plan succeed if it is not backed up by concrete policies to reduce monetary growth.7. The interest rate at the beginning and at the end of this experiment are equal.The ratio of money to prices (the level of real balances) must be higher when full employment is restored than in the initial state where there isunemployment: the money-market equilibrium condition can be satisfied only with a higher level of real balances if GNP is higher. Thus, the price level rises, but by less than twice its original level. If the interest rate were initially below its long-run level, the final result will be one with higher GNP and higher interest rates. Here, the final level of real balances may be higher or lower than the initial level, and we cannot unambiguously state whether the price level has more than doubled, less than doubled, or exactly doubled.8. The 1984 - 1985 money supply growth rate was 12.4 percent in the UnitedStates (100%*(641.0 - 570.3)/570.3) and 334.8 percent in Brazil (100%*(106.1 - 24.4)/24.4). The inflation rate in the United States during this period was 3.5 percent and in Brazil the inflation rate was 222.6 percent. The change in real money balances in the United States was approximately 12.4% - 3.5% = 8.9%, while the change in real money balances in Brazil was approximately 334.8% - 222.6% = 112.2%. The small change in the U.S. price level relative to the change in its money supply as compared to Brazil may be due to greater short-run price stickiness in the United States; the change in the price level in the United States represents 28 percent of the change in the money supply ((3.5/12.4)*100%) while in Brazil this figure is 66 percent ((222.6/334.8) *100%). There are, however, large differences between the money supply growth and the growth of the price level in both countries, which casts doubt on the hypothesis of money neutrality in the short run for both countries.9. Velocity is defined as real income divided by real balances or, equivalently,nominal income divided by nominal money balances (V=P*Y/M). Velocity in Brazil in 1985 was 13.4 (1418/106.1) while velocity in the United States was6.3 (4010/641). These differences in velocity reflected the different costs ofholding cruzados compared to holding dollars. These different costs were due to the high inflation rate in Brazil which quickly eroded the value of idle cruzados, while the relatively low inflation rate in the United States had a much less deleterious effect on the value of dollars.RE(M 1E 3E 2E 1(M 2E 4Figure 14-310. If an increase in the money supply raises real output in the short run, then thefall in the interest rate will be reduced by an outward shift of the money demand curve caused by the temporarily higher transactions demand for money. In figure 14-3, the increase in the money supply line from (M 1/P) to (M 2/P) is coupled with a shift out in the money demand schedule from L 1 to L 2. The interest rate falls from its initial value of R 1 to R 2, rather than to the lower level R 3, because of the increase in output and the resulting outward shift in the money demand schedule. Because the interest rate does not fall as much when output rises, the exchange rate depreciates by less: from its initial value of E 1 to E 2, rather than to E 3, in the diagram. In both cases we see the exchange rate appreciate back some to E4 in the long run. The difference is the overshoot is much smaller if there is a temporary increase in Y. Note, the fact that the increase in Y is temporary means that we still move to the same IP curve, as LR prices will still shift the same amount when Y returns to normal and we still have the same size M increase in both cases. A permanent increase in Y would involve a smaller expected price increase and a smaller shift in the IP curve.Undershooting occurs if the new short-run exchange rate is initially below its new long-run level. This happens only if the interest rate rises when the money supply rises – that is if GDP goes up so much that R does not fall, but increases. This is unlikely because the reason we tend to think that an increase in M may boost output is because of the effect of lowering interest rates, so we generally don’t think that the Y response can be so great as to increase R.。

薪酬管理外文文献翻译The existence of an agency problem in a corporation due to the separation of ownership and control has been widely studied in literatures. This paper examines the effects of management compensation schemes on corporate investment decisions. This paper is significant because it helps to understand the relationship between them. This understandings allow the design of an optimal management compensation scheme to induce the manager to act towards the goals and best interests of the company. Grossman and Hart (1983) investigate the principal agency problem. Since the actions of the agent are unobservable and the first best course of actions can not be achieved, Grossman and Hart show that optimal management compensation scheme should be adopted to induce the manager to choose the second best course of actions. Besides management compensation schemes, other means to alleviate the agency problems are also explored. Fama and Jensen (1983) suggest two ways for reducing the agency problem: competitive market mechanisms and direct contractual provisions. Manne (1965) argues that a market mechanism such as the threat of a takeover provided by the market can be used for corporate control. "Ex-post settling up" by the managerial labour market can also discipline managers and induce them to pursue the interests of shareholders. Fama (1980) shows that if managerial labour markets function properly, and if the deviation of the firm's actual performancefrom stockholders' optimum is settled up in managers' compensation, then the agency cost will be fully borne by the agent (manager).The theoretical arguments of Jensen and Meckling (1976) and Haugen and Senbet (1981), and empirical evidence of Amihud andLev (1981), Walking and Long (1984), Agrawal and Mandelker (1985), andBenston (1985), among others, suggest that managers' holding of common stock and stock options have an important effect on managerial incentives. For example, Benston finds that changes in the value of managers' stock holdings are larger than their annual employment income. Agrawal and Mandelker find that executive security holdings have a role in reducing agency problems. This implies that the share holdings and stock options of the managers are likely to affect the corporate investment decisions. A typical management scheme consists of flat salary, bonus payment and stock options. However, the studies, so far, only provide links between the stock options and corporate investment decisions. There are few evidences that the compensation schemes may have impacts on thecorporate investment decisions. This paper aims to provide a theoretical framework to study the effects of management compensation schemes on the corporate investment decisions. Assuming that the compensation schemes consist of flat salary, bonus payment, and stock options, I first examine the effects of alternative compensation schemes on corporate investment decisions under all-equity financing. Secondly, I examine the issue in a setting where a firm relies on debt financing. Briefly speaking, the findings are consistent with Amihud and Lev's results.Managers who have high shareholdings and rewarded by intensive profit sharing ratio tend to underinvest.However, the underinvestment problem can be mitigated by increasing the financial leverage. The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section II presents the model. Section HI discusses the managerial incentives under all-equity financing. Section IV examines the managerial incentives under debt financing. Section V discusses the empirical implications and presents the conclusions of the study.I consider a three-date two-period model. At time t0, a firm is established and goes public. There are now two kinds of owners in the firm, namely, the controlling shareholder and the atomistic shareholders. The proceeds from initial public offering are invested in some risky assets which generate an intermediate earnings, I, at t,. At the beginning, the firm also decides its financial structure. A manager is also hired to operate the firm at this time. The manager is entitled to hold a fraction of the firm's common stocks and stock options, a (where0<a<l), at the beginning of the first period. At time t,, the firm receives intermediate earnings, denoted by I, from the initial asset. At the same time, a new project investment is available to the firm. For simplicity, the model assumes that the firm needs all the intermediate earnings, I, to invest in the new project. If the project is accepted at t,, it produces a stochastic earnings Y in t2, such that Y={I+X, I-X}, with Prob[Y=I+X] = p and Prob[Y=I-X] = 1-p, respectively. The probability, p, is a uniform density function with an interval rangedfrom 0 to 1. Initially, the model also assumes that the net earnings, X, is less than initial investment, I. This assumption is reasonable since most of the investment can not earn a more than 100% rate of return. Later, this assumption is relaxed to investigate the effect of the extraordinarily profitable investment on the results. For simplicity, It is also assumed that there is no time value for the money and no dividend will be paid before t2. If the project is rejected at t,, the intermediate earnings, I, will be kept in the firm and its value at t2 will be equal to I. Effects of Management Compensation Schemes on Corporate Investment Decision Overinvestment versus UnderinvestmentA risk neutral investor should invest in a new project if it generates a positiexpected payoff. If the payoff is normally or symmetrically distributed, tinvestor should invest whenever the probability of making a positive earninggreater than 0.5. The minimum level of probability for making an investment the neutral investor is known as the cut-off probability. The project will generzero expected payoff at a cut-off probability. If the investor invests only in tprojects with the cut-off probability greater than 0.5, then the investor tendsinvest in the less risky projects and this is known as the underinvestment. Ifinvestor invests the projects with a cut-off probability less than 0.5, then tinvestor tends to invest in more risky projects and this is known as thoverinvestment. In the paper, it is assumed that the atomistic shareholders risk neutral, the manager and controlling shareholder are risk averse.It has been argued that risk-reduction activities are considered as managerial perquisites in the context of the agency cost model. Managers tend to engage in these risk-reduction activities to decrease their largely undiversifiable "employment risk" (Amihud and Lev 1981). The finding in this paper is consistent with Amihud and Lev's empirical result. Managers tend to underinvest when they have higher shareholdings and larger profit sharing percentage. This result is independent of the level of debt financing. Although the paper can not predict themanager's action when he has a large profit sharing percentage and the profit cashflow has high variance (X > I), it shows that the manager with high shareholding will underinvest in the project. This is inconsistent with the best interests of the atomistic shareholders. However, the underinvestment problem can be mitigated by increasing the financial leverage.The results and findings in this paper provides several testable hypotheses forfuture research. If the managers underinvest in the projects, the company willunderperform in long run. Thus the earnings can be used as a proxy forunderinvestment, and a negative relationship between earningsandmanagement shareholdings, stock options or profit sharing ratiois expected.As theunderinvestment problem can be alleviated by increasing the financialleverage, a positiverelationship between earnings and financial leverage isexpected.在一个公司由于所有权和控制权的分离的代理问题存在的文献中得到了广泛的研究。

财政学双语重点(重中之重啊!)1.Unified budget: The document which itemizes(逐项列出)all the federal government’s expenditures(支出)and revenues (收入).统一预算:联邦政府在一种文件中将其支出逐项列出。

2.substitution effect: The tendency of an individual to consume more of one good andless of another because of a decrease in the price of the former relative to the latter.替代效应一个人因一种商品相对于另一种商品的价格降低而多消费前者,少消费后者的倾向。

3. income effect :The effect of a price change on the quantity demanded(需求量)due exclusively(唯一的)to the fact that the consumer’s income has changed.收入效应价格变化对需求量的影响完全是由于消费者的实际收入的变化所致。

4. Pareto efficient: An allocation of resources such that no person can be made better off without making another person worse off.帕累托效率一种资源配置状态,在该状态下,如果不使一个人的境况变差就不可能使另一个人的境况变好。

5. Pareto improvement: A reallocation of resources that makes at least one person better off without making anyone else worse off.帕累托改进资源的重新配置可在不使任何人的境况变差的前提下,至少使一个人的境况变好。

1、绝对优势(Absolute advantage)如果一个国家用一单位资源生产的某种产品比另一个国家多,那么,这个国家在这种产品的生产上与另一国相比就具有绝对优势。

2、逆向选择(Adverse choice)在此状况下,保险公司发现它们的客户中有太大的一部分来自高风险群体。

3、选择成本(Alternative cost)如果以最好的另一种方式使用的某种资源,它所能生产的价值就是选择成本,也可以称之为机会成本。

4、需求的弧弹性( Arc elasticity of demand)如果P1和Q1分别是价格和需求量的初始值,P2 和Q2 为第二组值,那么,弧弹性就等于-(Q1-Q2)(P1+P2)/(P1-P2)(Q1+Q2)5、非对称的信息(Asymmetric information)在某些市场中,每个参与者拥有的信息并不相同。

例如,在旧车市场上,有关旧车质量的信息,卖者通常要比潜在的买者知道得多。

6、平均成本(Average cost)平均成本是总成本除以产量。

也称为平均总成本。

7、平均固定成本( Average fixed cost)平均固定成本是总固定成本除以产量。

8、平均产品(Average product)平均产品是总产量除以投入品的数量。

9、平均可变成本(Average variable cost)平均可变成本是总可变成本除以产量。

10、投资的β(Beta)β度量的是与投资相联的不可分散的风险。

对于一种股票而言,它表示所有现行股票的收益发生变化时,一种股票的收益会如何敏感地变化。

11、债券收益(Bond yield)债券收益是债券所获得的利率。

12、收支平衡图(Break-even chart)收支平衡图表示一种产品所出售的总数量改变时总收益和总成本是如何变化的。

收支平衡点是为避免损失而必须卖出的最小数量。

13、预算线(Budget line)预算线表示消费者所能购买的商品X和商品Y的数量的全部组合。

现如今越来越多的大学生选择做兼职英语作文全文共3篇示例,供读者参考篇1These days, the phenomenon of university students taking on part-time English tutoring jobs is becoming increasingly prevalent. As a student myself, I can attest to the growing trend among my peers to seek out such opportunities. There are numerous factors contributing to this paradigm shift, ranging from financial considerations to personal growth and skill development. In this essay, I will delve into the multifaceted motivations behind this phenomenon and explore its implications for both students and the broader educational landscape.One of the primary drivers behind the surge in part-time English tutoring jobs among university students is undoubtedly the financial aspect. The ever-rising cost of higher education, coupled with the escalating expenses associated with living in urban areas, has placed a significant financial burden on many students and their families. Consequently, taking on a part-time job becomes a necessity rather than a choice for some students. English tutoring, in particular, presents an attractive option dueto the high demand for proficiency in the language, both domestically and globally.Moreover, the flexibility of English tutoring jobs allows students to strike a balance between their academic commitments and earning an income. Unlike traditionalpart-time jobs that require rigid schedules, tutoring can often be arranged around class schedules, providing students with the freedom to manage their time effectively. This flexibility is especially appealing to those juggling demanding coursework and extracurricular activities, enabling them to maintain their academic performance while supplementing their income.Beyond the financial incentives, however, engaging inpart-time English tutoring can also foster personal growth and skill development for university students. The act of teaching itself requires a deep understanding of the subject matter, as well as the ability to convey complex concepts in a clear and engaging manner. This process of breaking down information and presenting it in a comprehensible way can enhance the tutor's own grasp of the material, reinforcing their knowledge and communication skills.Furthermore, tutoring exposes students to a diverse range of learners, each with their unique learning styles, backgrounds,and challenges. Adapting to these varying needs and tailoring their teaching approach accordingly cultivates invaluable interpersonal skills, such as empathy, patience, and cultural sensitivity. These soft skills are not only beneficial in the context of tutoring but also invaluable in any professional setting, providing students with a competitive edge in the job market upon graduation.Additionally, the experience of tutoring can serve as a stepping stone for those considering careers in education or related fields. It offers a practical opportunity to explore teaching methodologies, classroom management techniques, and curriculum development. For aspiring educators, this hands-on exposure can be invaluable, allowing them to refine their skills and gain insights into the realities of the profession before committing to it fully.However, it is essential to acknowledge the potential challenges and drawbacks associated with juggling part-time work and academic responsibilities. Striking the right balance can be a delicate endeavor, and the pressure of managing multiple commitments can lead to stress and burnout if not approached with careful time management and self-care strategies.Moreover, the quality of tutoring services provided by students may vary, potentially leading to inconsistent learning experiences for the tutees. While many university students possess a strong command of the English language, they may lack formal training in teaching methodologies or experience in lesson planning, which could impact the effectiveness of their instruction.To address these concerns, it is crucial for universities and educational institutions to provide adequate support and resources to student tutors. This could include offering training programs, access to teaching materials, and mentorship from experienced educators. By equipping student tutors with the necessary tools and guidance, the quality of their services can be enhanced, ensuring a rewarding experience for both the tutors and their students.In conclusion, the growing trend of university students engaging in part-time English tutoring jobs is a multi-faceted phenomenon driven by a combination of financial pressures, personal growth opportunities, and career exploration. While this path presents numerous benefits, such as financial independence, skill development, and practical experience, italso comes with challenges that require careful navigation and institutional support.As the demand for English proficiency continues to rise globally, the role of student tutors in addressing this need becomes increasingly significant. By embracing this trend and fostering a supportive environment for student tutors, universities can not only provide valuable services to the community but also equip their students with invaluable experiences and skills that will serve them well beyond their academic years.篇2The Surge of the Student Side HustleAs a university student myself, I can't help but notice the increasing trend of my peers taking on part-time jobs or "side hustles" alongside their academic commitments. Gone are the days when a student's sole focus was on their studies. Nowadays, it seems like everyone is juggling multiple responsibilities, be it working at a cafe, tutoring, or running an online business. This phenomenon raises several questions: What's driving this shift? What are the pros and cons? And is it a sustainable way of life?The Root CausesThe primary driver behind this surge in student side hustles is undoubtedly financial pressure. With the ever-rising cost of living and tuition fees, many students find themselves struggling to make ends meet on a student budget alone. Taking on a part-time job becomes a necessity to cover expenses like rent, groceries, and textbooks. Even for those receiving financial aid or support from their families, the desire for supplemental income and a taste of financial independence is strong.Another factor fueling this trend is the changing perception of work-life balance among younger generations. Unlike previous cohorts who may have viewed work as separate from their personal lives, today's students often seek a more integrated approach. They crave experiences that align with their values, interests, and long-term career goals. A side hustle allows them to explore these avenues while still pursuing their academic degrees.The ProsOne of the most significant advantages of having a side hustle is the financial freedom it provides. With a steady stream of income, students can alleviate the burden of student loans, save for future endeavors, or simply enjoy a more comfortable lifestyle. Additionally, the skills and experiences gained throughthese part-time jobs can be invaluable in developing awell-rounded skillset and enhancing future employability.Soft skills like time management, communication, and problem-solving are honed through the juggling act of balancing studies and work. Furthermore, some side hustles, such as freelance writing or graphic design, directly align with students' academic pursuits, allowing them to apply their knowledge in practical settings and potentially kickstart their careers before graduation.The ConsWhile the benefits of side hustles are appealing, they come with their fair share of challenges. The most obvious one is the strain on a student's already limited time and energy resources. Balancing academics, extracurricular activities, social life, and a part-time job can quickly lead to burnout and compromised academic performance if not managed carefully.Moreover, some side hustles may not align with a student's long-term career goals, leading to a dispersion of focus and potential opportunity costs. There's also the risk of exploitation, as some employers may take advantage of students' desperation for income by offering unfair wages or working conditions.Finding the Sweet SpotDespite the potential drawbacks, the allure of side hustles remains strong for many students. The key lies in striking the right balance and making informed choices. Students should carefully evaluate the time commitment and workload of a potential side hustle, ensuring it doesn't impede their academic progress or mental well-being.Prioritizing time management and setting clear boundaries are crucial. Some students find success by dedicating specific blocks of time to their side hustles, treating them like scheduled classes or commitments. Others opt for more flexible arrangements, such as freelance work or online ventures that can be managed around their academic schedules.Additionally, students should strive to align their side hustles with their long-term career aspirations. If a job doesn't contribute to their skillset or professional development, it may be worth reconsidering. Conversely, opportunities that allow for practical experience or networking within their desired field can be invaluable investments.The Role of UniversitiesAs this trend continues to gain momentum, universities have a responsibility to adapt and support their students in navigating the side hustle landscape. Offering workshops on time management, entrepreneurship, and financial literacy could equip students with the tools they need to balance their commitments effectively.Furthermore, universities could explore partnerships with local businesses or organizations to facilitate part-time employment opportunities that align with students' academic programs and career goals. On-campus job fairs or internship programs tailored to students' interests could be valuable resources.Embracing the New NormAs a student myself, I can attest to the challenges and rewards of juggling a side hustle alongside my studies. While it's certainly not an easy feat, the experiences and skills gained have been invaluable. From learning to prioritize and manage my time effectively to developing a stronger work ethic and financial literacy, my side hustle has been a catalyst for personal growth.For many of us, side hustles are no longer just a temporary solution but a way of life that blurs the lines between work and academics. As we navigate this new reality, it's crucial to strike abalance, make informed choices, and leverage the resources available to us.The surge of student side hustles is a testament to the adaptability and entrepreneurial spirit of today's youth. With the right mindset and support systems in place, we can embrace this trend as an opportunity for personal and professional growth, paving the way for a generation of well-rounded, financially savvy, and experience-rich graduates.篇3More and More College Students Are Choosing to DoPart-Time JobsCollege life is meant to be a once-in-a-lifetime experience filled with new adventures, personal growth, and unforgettable memories. However, the harsh reality is that the cost of higher education has been skyrocketing, leaving many students struggling to make ends meet. As a result, an increasing number of college students are turning to part-time jobs to supplement their income and alleviate the financial burden.I can personally attest to the challenges of financing a college education. Coming from a middle-class family, the tuition fees, textbooks, housing, and other associated costsquickly added up, leaving me with a substantial financial burden. It was then that I realized the importance of finding a part-time job to help cover these expenses.At first, the prospect of balancing studies and work seemed daunting. I worried about the potential impact on my academic performance and social life. However, after careful consideration and speaking with friends who had successfully juggled both responsibilities, I decided to take the plunge and seek out a part-time job.The process of finding a suitable job was not without its challenges. I sifted through countless job postings, attended interviews, and eventually landed a position as a barista at a local coffee shop. While the work itself was demanding, with long hours on my feet and the need to multitask constantly, it taught me valuable lessons in time management, customer service, and the importance of a strong work ethic.As I settled into my new routine, I quickly discovered the benefits of having a part-time job. Firstly, the steady income provided me with a sense of financial independence and alleviated the burden on my parents, who had already sacrificed so much for my education. Secondly, the job allowed me to develop essential soft skills that would undoubtedly proveinvaluable in my future career. Working in a fast-paced environment taught me how to handle stress, communicate effectively, and work collaboratively with a diverse team.Moreover, the experience of holding a part-time job instilled in me a newfound appreciation for the value of hard work and the importance of budgeting. I became more mindful of my spending habits, learning to prioritize necessities over luxuries and seeking out ways to save money whenever possible.Despite the challenges of balancing work and studies, I found that having a part-time job actually improved my academic performance. The structure and discipline required to manage my time effectively spilled over into my studies, as I became more organized and efficient in my approach to coursework and assignments.Furthermore, the social aspect of working alongside fellow students and individuals from various backgrounds broadened my perspective and enriched my college experience. I formed lasting friendships with coworkers who shared similar struggles and aspirations, and we often supported one another through the inevitable ups and downs of student life.Of course, the experience was not without its drawbacks. There were times when the demands of work and studiescollided, causing stress and anxiety. Late-night study sessions and early morning shifts took their toll, and I found myself longing for more free time to engage in extracurricular activities or simply relax.However, these challenges only served to strengthen my resolve and taught me valuable lessons in prioritization and self-care. I learned to set boundaries, communicate my needs effectively, and seek support from friends, family, and campus resources when necessary.As I reflect on my college experience, I can say with certainty that taking on a part-time job was one of the best decisions I made. Not only did it provide me with financial stability, but it also equipped me with a diverse set of skills and experiences that have prepared me for the challenges of the professional world.Looking ahead, I know that the lessons I learned from balancing work and studies will continue to serve me well. The determination, resilience, and time management skills I honed during those years will undoubtedly be invaluable assets as I embark on my career journey.To my fellow students considering taking on a part-time job, I encourage you to embrace the challenge. While it may seem daunting at first, the rewards are immense. Not only will you gainfinancial independence and valuable work experience, but you will also develop essential life skills that will set you apart from your peers.However, it is crucial to strike a balance and prioritize your well-being. Seek out support from campus resources, communicate openly with your professors and employers, and remember to carve out time for self-care and leisure activities.In conclusion, the decision to take on a part-time job during college is a personal one that requires careful consideration of individual circumstances. However, for those willing to embrace the challenge, the rewards are numerous and far-reaching. Not only does it provide financial stability, but it also equips students with invaluable skills and experiences that will serve them well beyond their college years.。

分享返回分享首页»分享经济学专业英语词汇整理来源:金相彬S.K.的日志1、Ability-to-pay principle(of taxation)(税收的)支付能力原则按照纳税人支付能力确定纳税负担的原则。

纳税人支付能力依据其收人或财富来衡量。

这一原则并不说明某经济状况较好的人到底该比别人多负担多少。

2、Absolute advantage 绝对优势如果一个国家用一单位资源生产的某种产品比另一个国家多,那么,这个国家在这种产品的生产上与另一国相比就具有绝对优势。

3、Accelerator principle 加速原理解释产出率变动同方向地引致投资需求变动的理论。

4、Actual, cyclical, and structural budget 实际预算、周期预算和结构预算实际预算的赤字或盈余指的是某年份实际记录的赤字或盈余。

实际预算可划分成结构预算和周期预算。

结构预算假定经济在潜在产出水平上运行,并据此测算该经济条件下的政府税入、支出和赤字等指标。

周期预算基于所预测的商业周期(及其经济波动)对预算的影响。

5、Adaptive expectations 适应性预期见预期(expectations)。

6、Adjustable peg 可调整钉住一种(固定)汇率制度。

在该制度下,各国货币对其他货币保持一种固定的或曰"钉住的"汇率。

当某些基本因素发生变动、原先汇率失去合理依据的时候,这种汇率便不时地趋于凋整。

在1944-1971年期间,世界各主要货币都普遍实行这种制度,称为"布雷顿森林体系"。

7、Administered(or inflexible)prices 管理(或非浮动)价格特指某类价格的术语。

按照有关规定,这类价格在某一段时间内、在若干种交易中能够维持不变。

(见价格浮动 price flexibility)8、Adverse choice/selection 逆向选择一种市场不灵。

货币贬值影响英语作文The Impact of Currency Depreciation。

Currency depreciation refers to the decrease in the value of a country's currency in relation to other currencies. This can have a significant impact on acountry's economy, affecting everything from trade to inflation. In this essay, we will discuss the impact of currency depreciation on various aspects of the economy.One of the most immediate effects of currency depreciation is its impact on trade. When a country's currency depreciates, its exports become cheaper for foreign buyers, while imports become more expensive for domestic consumers. This can lead to an increase in exports and a decrease in imports, which can help to improve the country's trade balance. However, it can also lead to higher prices for imported goods, which can increase the cost of living for consumers.Currency depreciation can also have an impact on inflation. When a country's currency depreciates, the cost of imported goods and raw materials increases, which can lead to higher production costs for domestic producers. This can lead to an increase in the prices of goods and services, which can contribute to inflation. In addition, currency depreciation can also lead to higher prices for imported goods, which can further contribute to inflation.Currency depreciation can also have an impact on the financial markets. When a country's currency depreciates,it can lead to capital flight as investors move their money to countries with stronger currencies. This can lead to a decrease in the value of the country's currency, as well as a decrease in the value of its financial assets. In addition, currency depreciation can also lead to higher interest rates, as the central bank may raise interest rates in an attempt to stabilize the currency.In conclusion, currency depreciation can have a significant impact on a country's economy, affecting everything from trade to inflation. While it can lead to anincrease in exports and a decrease in imports, it can also lead to higher prices for imported goods and raw materials, which can contribute to inflation. In addition, it can also lead to capital flight and higher interest rates, which can further impact the country's economy. Therefore, it is important for policymakers to carefully consider the potential impact of currency depreciation and take appropriate measures to mitigate its effects.。

人民币贬值英语作文The Depreciation of Chinese Yuan。

In recent years, the depreciation of Chinese Yuan has become a hot topic in the global financial market. As the value of Chinese currency continues to drop, it has sparked concerns and debates about its impact on the global economy. In this essay, we will explore the reasons behind the depreciation of Chinese Yuan and its potential consequences.There are several factors contributing to the depreciation of Chinese Yuan. One of the main reasons isthe trade war between China and the United States. The escalating tariffs and trade tensions have put pressure on the Chinese economy, leading to a decrease in the value of its currency. Moreover, the slowing economic growth and the increasing debt burden have also played a role in the devaluation of Chinese Yuan. In addition, the People's Bank of China's decision to lower the daily reference rate forthe currency has further accelerated its depreciation.The depreciation of Chinese Yuan has raised concerns about its impact on the global economy. One of thepotential consequences is the negative effect on international trade. As Chinese goods become cheaper due to the devaluation of its currency, it may lead to a surge in exports and a decrease in imports, which could disrupt the balance of trade and cause trade tensions with other countries. Furthermore, the depreciation of Chinese Yuan could also trigger a currency war, as other countries may devalue their currencies in response, leading to a downward spiral of global currency values.Moreover, the depreciation of Chinese Yuan could have a significant impact on the global financial market. It may lead to capital outflows from China, as investors seek to protect their assets from the devaluation of its currency. This could lead to a tightening of global liquidity and an increase in market volatility. In addition, the depreciation of Chinese Yuan could also affect the value of other currencies, as it may lead to a revaluation of exchange rates and a reshuffling of global currencyreserves.In response to the depreciation of Chinese Yuan, the Chinese government has taken measures to stabilize its currency. It has intervened in the foreign exchange market to support the value of its currency and has implemented capital controls to prevent capital outflows. Moreover, the government has also pledged to pursue a more flexible exchange rate policy and to promote economic reforms to address the underlying issues contributing to the devaluation of Chinese Yuan.In conclusion, the depreciation of Chinese Yuan has raised concerns about its impact on the global economy. While it may lead to a surge in Chinese exports and a decrease in imports, it could also trigger a currency war and disrupt the global financial market. However, the Chinese government has taken measures to stabilize its currency and address the underlying issues contributing to its devaluation. It remains to be seen how the depreciation of Chinese Yuan will unfold and its potential consequences on the global economy.。

宏观经济学第十五章MEASUREING A NATION’S INCOME一国收入的衡量Microeconomics the study of how households and firms make decisions and how they interact in markets.微观经济学:研究家庭和企业如何做出决策,以及他们如何在市场上相互交易。

Macroeconomics the study of economy-wide phenomena,including inflation,unemployment,and economic growth宏观经济学:研究整体经济现象,包括通货膨胀、失业和经济增长.GDP is the market value of final goods and services produced within a country in a given period of time.国内生产总值GDP:给定时期的一个经济体内生产的所有最终产品和服务的市场价值Consumption is spending by households on goods and services, with the exception of purchased of new housing.消费:除了购买新住房,家庭用于物品与劳务的支出。

Investment is spending on capital equipment inventories, and structures, including household purchases of new housing。

投资:用于资本设备、存货和建筑物的支出,包括家庭用于购买新住房的支出.Government purchases are spending on goods and services by local, state, and federal government.政府支出:地方、州和联邦政府用于物品和与劳务的支出.Net export is spending on domestically produced goods by foreigners (exports) minus spending on foreign goods by domestic residents (imports)净出口:外国人对国内生产的物品的支出(出口)减国内居民对外国物品的支出(进口)。

职场上男女是否平等英语作文In today's workplace, we often talk about gender equality, but how real is it? From my observations, progress has been made, but challenges remain.I've seen women rise to leadership positions in various industries, proving their capabilities and earning respect. They bring a unique perspective and often excel in team-building and communication. But let's not forget, there are still glass ceilings that need to be broken.On the other hand, men are also facing changes. More and more companies are promoting flexible work hours and family-friendly policies, which benefits both genders. But sometimes, traditional expectations of men as breadwinners still linger.One thing I've noticed is the increasing focus on inclusivity and diversity. This isn't just about gender;it's about creating a workplace where everyone feels valuedand can contribute their best. And that's a good thing, right?Pay equity is another aspect where we still have workto do. Although laws and policies aim to ensure fair pay, unconscious biases can still creep in. But awareness is growing, and that's a step in the right direction.In conclusion, while we're not there yet, I believewe're moving towards a more equal workplace. It's a journey, and we all have a role to play in making it happen.。

利益受到损害的英语作文Title: The Consequences of Compromised Interests。

In our journey through life, we often find ourselves navigating a complex web of interests, both personal and collective. However, there are moments when these interests are compromised, leading to various repercussions. Today, we delve into the intricacies of such situations and explore the far-reaching effects of compromised interests.Firstly, it's imperative to understand what constitutes a compromised interest. Essentially, it occurs when the pursuit or protection of one's interests clashes with those of others, resulting in a loss or detriment to one or both parties involved. This can manifest in various spheres of life, be it in personal relationships, business dealings, or broader societal contexts.In personal relationships, compromised interests can sow seeds of discord and resentment. Consider a scenariowhere two individuals have differing aspirations or values. If one person consistently prioritizes their own goals over their partner's, it can lead to feelings of neglect and dissatisfaction. Over time, this imbalance can erode trust and intimacy, ultimately damaging the relationship irreparably.Similarly, in the realm of business and finance, compromised interests can have profound consequences. Take, for instance, a company embroiled in a conflict of interest between maximizing profits and adhering to ethical practices. If profit becomes the sole driving force, it may resort to exploitative labor practices or environmental degradation, jeopardizing the well-being of employees and communities. Such actions not only tarnish the company's reputation but also undermine its long-term viability.Moreover, compromised interests often manifest on a societal scale, giving rise to inequality and injustice. Consider the disparities in access to resources and opportunities prevalent in many societies. When the interests of marginalized groups are overlooked ordisregarded in favor of the privileged few, it perpetuates cycles of poverty and disenfranchisement. This not only undermines social cohesion but also stunts overall economic growth and development.Furthermore, compromised interests can have significant psychological repercussions. When individuals feel that their needs and desires are consistently sidelined, it can lead to feelings of powerlessness and disillusionment. This can manifest as anxiety, depression, or even anger, further exacerbating tensions in personal and social relationships.In light of these consequences, it becomes imperative to address compromised interests proactively. This necessitates fostering open communication, empathy, and a willingness to compromise for the greater good. In personal relationships, this might involve cultivating a deeper understanding of each other's needs and finding common ground through respectful dialogue. In business and governance, it requires prioritizing ethical considerations and stakeholder engagement over short-term gains.Additionally, combating compromised interests requires systemic change at both the institutional and societal levels. This entails enacting policies that promote fairness, equality, and accountability, while also challenging entrenched power dynamics and privilege. By fostering a culture of transparency and inclusivity, we can mitigate the adverse effects of compromised interests and build a more just and equitable world for all.In conclusion, compromised interests have far-reaching consequences that permeate every aspect of our lives. Whether in personal relationships, business dealings, or broader societal contexts, the repercussions ofprioritizing self-interest at the expense of others are profound and multifaceted. However, by recognizing the importance of mutual respect, empathy, and collective well-being, we can navigate these complexities and strive towards a more harmonious and equitable future.。