BTBU_3.1 Shareholder voting on auditor selection, audit fees, and audit quality

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:426.95 KB

- 文档页数:24

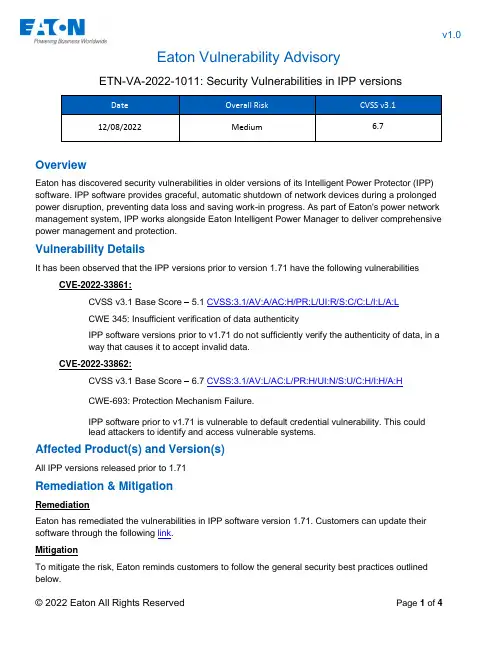

v1.0Eaton Vulnerability Advisory© 2022 Eaton All Rights Reserved Page 1 of 4ETN-VA-2022-1011: Security Vulnerabilities in IPP versionsOverviewEaton has discovered security vulnerabilities in older versions of its Intelligent Power Protector (IPP) software. IPP software provides graceful, automatic shutdown of network devices during a prolonged power disruption, preventing data loss and saving work-in progress. As part of Eaton's power network management system, IPP works alongside Eaton Intelligent Power Manager to deliver comprehensive power management and protection.Vulnerability DetailsIt has been observed that the IPP versions prior to version 1.71 have the following vulnerabilitiesCVE-2022-33861:CVSS v3.1 Base Score – 5.1 CVSS:3.1/AV:A/AC:H/PR:L/UI:R/S:C/C:L/I:L/A:LCWE 345: Insufficient verification of data authenticityIPP software versions prior to v1.71 do not sufficiently verify the authenticity of data, in away that causes it to accept invalid data.CVE-2022-33862:CVSS v3.1 Base Score – 6.7 CVSS:3.1/AV:L/AC:L/PR:H/UI:N/S:U/C:H/I:H/A:HCWE-693: Protection Mechanism Failure.IPP software prior to v1.71 is vulnerable to default credential vulnerability. This couldlead attackers to identify and access vulnerable systems.Affected Product(s) and Version(s)All IPP versions released prior to 1.71Remediation & MitigationRemediationEaton has remediated the vulnerabilities in IPP software version 1.71. Customers can update their software through the following link .MitigationTo mitigate the risk, Eaton reminds customers to follow the general security best practices outlined below.General Security Best Practices•Restrict exposure to external networks for all control system devices and/or systems and ensure that they are not directly accessible from the open Internet.•Deploy control system networks and remote devices behind barrier devices (e.g. firewalls, data diodes) and isolate them from business networks.•Remote access to control system networks should be made available on a strict need-to-use basis. Remote access should use secure methods, such as Virtual Private Networks (VPNs), updated to the most current version available.•Regularly update/patch software/applications to latest versions available, as applicable.•Enable audit logs on all devices and applications.•Disable/deactivate unused communication channels, TCP/UDP ports and services (e.g., SNMP, FTP, BootP, DHCP, etc.) on networked devices.•Create security zones for devices with common security requirements using barrier devices(e.g. firewalls, data diodes).•Change default passwords following initial startup. Use complex secure passwords or passphrases.•Perform regular security assessments and risk analysis of networked control systems.For more details on cybersecurity best practices and leverage Eaton’s Cybersecurity as a Service, please consult the following –•Eaton offers a suite of cybersecurity assessment and life-cycle management services to help identify vulnerabilities and secure your operational technology network. These services canhelp you complete the recommended remediation and mitigation actions and strengthen your overall network security. More information about these services is available at/cybersecurityservices. If you need immediate support, please call +1-800-498-2678 to connect with a representative.•Cybersecurity Considerations for Electrical Distribution Systems (WP152002EN)•Cybersecurity Best Practices Checklist Reminder (WP910003EN)Additional Support and InformationFor additional information, including a list of vulnerabilities that have been reported on our products and how to address them, please visit our Cybersecurity web site /cybersecurity, or contact us at ***************.Legal Disclaimer:TO THE MAXIMUM EXTENT PERMITTED BY APPLICABLE LAW, INFORMATION PROVIDED IN THIS DOCUMENT IS PROVIDED “AS IS” WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND. EATON, ITS AFFILIATES, SUBSIDIARIES, AND AUTHORIZED REPRESENTATIVES HEREBY DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES AND CONDITIONS OF ANY KIND EITHER EXPRESS, IMPLIED, STATUTORY, OR OTHERWISE, INCLUDING, BUT WITHOUT LIMITATION, ANY IMPLIED WARRANTIES AND/OR CONDITIONS OF SECURITY,COMPLETENESS, TIMELINESS, ACCURACY, MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. YOU ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR REVIEWING THE USER MANUAL FOR YOUR DEVICES AND GAINING KNOWLEDGE ON CYBERSECURITY MEASURES. YOU SHOULD TAKE THE NECESSARY STEPS TO ENSURE THAT YOUR DEVICE OR SOFTWARE IS PROTECTED, INCLUDING CONTACTING AN EATON PROFESSIONAL. SOME JURISDICTIONS DO NOT ALLOW THE EXCLUSION OF IMPLIED WARRANTIES OR LIMITATIONS, SO THE ABOVE LIMITATIONS MAY NOT APPLY. TO THE EXTENT PERMITTED BY LAW, IN NO EVENT WILL EATON OR ITS AFFILIATES, OFFICERS, DIRECTORS, AND/OR EMPLOYEES, BE LIABLE FOR ANY LOSS OR DAMAGE OF ANY KIND WHATSOEVER, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, ANY DIRECT, INDIRECT, INCIDENTAL, SPECIAL, STATUTORY, PUNITIVE, ACTUAL, LIQUIDATED, EXEMPLARY, CONSEQUENTIAL OR OTHER DAMAGES,EVEN IF EATON HAS BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES. THE USE OF THIS NOTIFICATION, INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN, OR MATERIALS LINKED TO IT ARE AT YOUR OWN RISK. EATON RESERVES THE RIGHT TO UPDATE OR CHANGE THIS NOTIFICATION AT ANY TIME AND AT ITS SOLE DISCRETION.About Eaton:Eaton is a power management company. We provide energy-efficient solutions that help our customers effectively manage electrical and mechanical power more efficiently, safely, and sustainably. Eaton is dedicated to improving the quality of life and the environment using power management technologies and services. Eaton has approximately 85,000 employees and sells products to customers in more than 175 countries.Revision Control:Office:Eaton, 1000 Eaton BoulevardCleveland, OH 44122, United States。

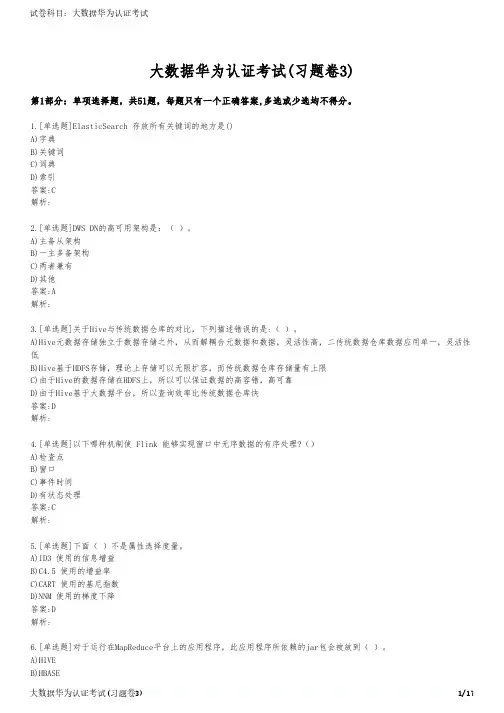

大数据华为认证考试(习题卷3)第1部分:单项选择题,共51题,每题只有一个正确答案,多选或少选均不得分。

1.[单选题]ElasticSearch 存放所有关键词的地方是()A)字典B)关键词C)词典D)索引答案:C解析:2.[单选题]DWS DN的高可用架构是:( )。

A)主备从架构B)一主多备架构C)两者兼有D)其他答案:A解析:3.[单选题]关于Hive与传统数据仓库的对比,下列描述错误的是:( )。

A)Hive元数据存储独立于数据存储之外,从而解耦合元数据和数据,灵活性高,二传统数据仓库数据应用单一,灵活性低B)Hive基于HDFS存储,理论上存储可以无限扩容,而传统数据仓库存储量有上限C)由于Hive的数据存储在HDFS上,所以可以保证数据的高容错,高可靠D)由于Hive基于大数据平台,所以查询效率比传统数据仓库快答案:D解析:4.[单选题]以下哪种机制使 Flink 能够实现窗口中无序数据的有序处理?()A)检查点B)窗口C)事件时间D)有状态处理答案:C解析:5.[单选题]下面( )不是属性选择度量。

A)ID3 使用的信息增益B)C4.5 使用的增益率C)CART 使用的基尼指数D)NNM 使用的梯度下降答案:D解析:C)HDFSD)DB答案:C解析:7.[单选题]关于FusionInsight HD Streaming的Supervisor描述正确的是:( )。

A)Supervisor负责资源的分配和任务的调度B)Supervisor负责接受Nimbus分配的任务,启动停止属于自己管理的Worker进程C)Supervisor是运行具体处理逻辑的进程D)Supervisor是在Topology中接收数据然后执行处理的组件答案:B解析:8.[单选题]在有N个节点FusionInsight HD集群中部署HBase时、推荐部署( )个H Master进程,( )个Region Server进程。

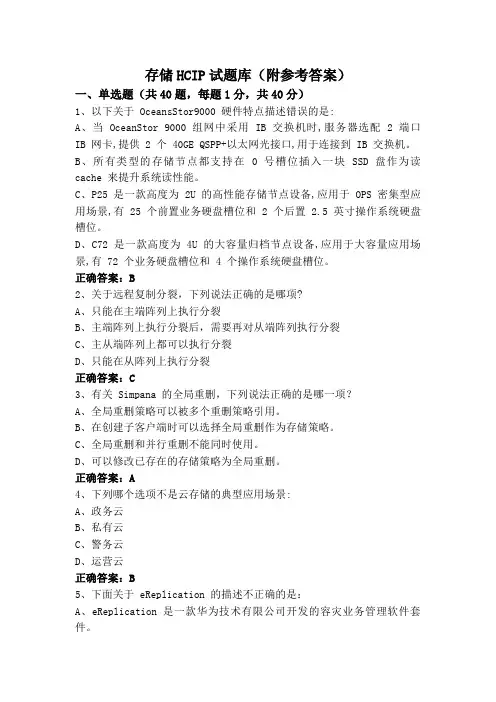

存储HCIP试题库(附参考答案)一、单选题(共40题,每题1分,共40分)1、以下关于 OceansStor9000 硬件特点描述错误的是:A、当 OceanStor 9000 组网中采用 IB 交换机时,服务器选配 2 端口IB 网卡,提供 2 个 40GE QSPP+以太网光接口,用于连接到 IB 交换机。

B、所有类型的存储节点都支持在 0 号槽位插入一块 SSD 盘作为读cache 来提升系统读性能。

C、P25 是一款高度为 2U 的高性能存储节点设备,应用于 OPS 密集型应用场景,有 25 个前置业务硬盘槽位和 2 个后置 2.5 英寸操作系统硬盘槽位。

D、C72 是一款高度为 4U 的大容量归档节点设备,应用于大容量应用场景,有 72 个业务硬盘槽位和 4 个操作系统硬盘槽位。

正确答案:B2、关于远程复制分裂,下列说法正确的是哪项?A、只能在主端阵列上执行分裂B、主端阵列上执行分裂后,需要再对从端阵列执行分裂C、主从端阵列上都可以执行分裂D、只能在从阵列上执行分裂正确答案:C3、有关 Simpana 的全局重删,下列说法正确的是哪一项?A、全局重删策略可以被多个重删策略引用。

B、在创建子客户端时可以选择全局重删作为存储策略。

C、全局重删和并行重删不能同时使用。

D、可以修改已存在的存储策略为全局重删。

正确答案:A4、下列哪个选项不是云存储的典型应用场景:A、政务云B、私有云C、警务云D、运营云正确答案:B5、下面关于 eReplication 的描述不正确的是:A、eReplication 是一款华为技术有限公司开发的容灾业务管理软件套件。

B、eReplication 是一款华为技术有限公司开发的备份业务管理软件套件。

C、eReplication 支持可视化管理,保护组和恢复计划的执行状态一目了然。

正确答案:B6、在Simpana 软件中,包括以下组件1MediaAgert 2CommServe 3iDataAgent下面关于升级组件顺序的描述正确的是A、3->1->2B、1->2->3C、1->3->2D、2->1->3正确答案:D7、在 Oceanstor 9000 中,对 WushanFS 全局缓存技术理解错误的是哪一项A、某一节点缓存中的数据不能被其他节点的读写业务命中B、全局缓存技术有助于提升节点内存资源共享C、WushanFS 中的 Global Cache 将所有存储服务器上的内存空间在逻辑上组成一个整体内存资源池D、WushanFS 利用分布式锁实现全局缓存数据管理,同一业务数据只在某个节点缓存一份,当其他节点需要访问该数据时,通过申请锁,获取该缓存数据正确答案:A8、以下关于 Oceanstor 9000 的物理分域描述错误的是哪一项?A、物理分域是一种隔离故障的有效手段B、Oceanstor 9000 通过节点池与分级的方法来实现物理分域C、管理员最少要将 2 个存储节点加入一个分域中D、某些节点故障,会造成与这些节点在一个物理分域内的其他节点上的数据的可靠性级别降低正确答案:C9、关于合成全备份以下说法错误的是哪一项?A、在备份服务器或介质服务器上,根据先前的全备份和其它增量或差异备份,合并生成全备份。

Kafka学习笔记之kafka常见报错及解决⽅法(topic类、⽣产消费类、启动类)0x01 启动报错1.1 第⼀种错误2017-02-17 17:25:29,224] FATAL Fatal error during KafkaServer startup. Prepare to shutdown (kafka.server.KafkaServer)mon.KafkaException: Failed to acquire lock on file .lock in /var/log/kafka-logs. A Kafka instance in another process or thread is using this directory.at kafka.log.LogManager$$anonfun$lockLogDirs$1.apply(LogManager.scala:100)at kafka.log.LogManager$$anonfun$lockLogDirs$1.apply(LogManager.scala:97)at scala.collection.TraversableLike$$anonfun$map$1.apply(TraversableLike.scala:234)at scala.collection.TraversableLike$$anonfun$map$1.apply(TraversableLike.scala:234)at scala.collection.IndexedSeqOptimized$class.foreach(IndexedSeqOptimized.scala:33)at scala.collection.mutable.WrappedArray.foreach(WrappedArray.scala:35)at scala.collection.TraversableLike$class.map(TraversableLike.scala:234)at scala.collection.AbstractTraversable.map(Traversable.scala:104)at kafka.log.LogManager.lockLogDirs(LogManager.scala:97)at kafka.log.LogManager.<init>(LogManager.scala:59)at kafka.server.KafkaServer.createLogManager(KafkaServer.scala:609)at kafka.server.KafkaServer.startup(KafkaServer.scala:183)at io.confluent.support.metrics.SupportedServerStartable.startup(SupportedServerStartable.java:100)at io.confluent.support.metrics.SupportedKafka.main(SupportedKafka.java:49)解决⽅法:Failed to acquire lock on file .lock in /var/log/kafka-logs.--问题原因是有其他的进程在使⽤kafka,ps -ef|grep kafka,杀掉使⽤该⽬录的进程即可;1.2 第⼆种错误:对index⽂件⽆权限把⽂件的权限更改为正确的⽤户名和⽤户组即可;⽬录/var/log/kafka-logs/,其中__consumer_offsets-29是偏移量;1.3 第三种⽣产消费报错:jaas连接有问题kafka_client_jaas.conf⽂件配置有问题16环境上/opt/dataload/filesource_wangjuan/conf下kafka_client_jaas.confKafkaClient {com.sun.security.auth.module.Krb5LoginModule requireduseKeyTab=truestoreKey=truekeyTab="/home/client/keytabs/client.keytab"serviceName="kafka"principal="client/dcp@";};0x02 ⽣产者报错2.1 第⼀种:⽣产者向topic发送消息失败[2017-03-09 09:16:00,982] [ERROR] [startJob_Worker-10] [DCPKafkaProducer.java line:62] produceR向topicdf02211发送信息出现异常mon.KafkaException: Failed to construct kafka producerat org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.KafkaProducer.<init>(KafkaProducer.java:335)原因是配置⽂件:kafka_client_jaas.conf中配置有问题,keyTab的路径不对,导致的;2.2 第⼆种:⽣产消费报错: Failed to construct kafka producer报错关键信息:Failed to construct kafka producer解决⽅法:配置⽂件问题:KafkaClient中serviceName应该是kafka,之前配置成了zookeeper;重启后,就好了;配置⽂件如下:KafkaServer {com.sun.security.auth.module.Krb5LoginModule requireduseKeyTab=truestoreKey=trueuseTicketCache=falseserviceName=kafkakeyTab="/etc/security/keytabs/kafka.service.keytab"principal="kafka/dcp16@";};KafkaClient {com.sun.security.auth.module.Krb5LoginModule requireduseKeyTab=truestoreKey=trueserviceName=kafkakeyTab="/etc/security/keytabs/kafka.service.keytab"principal="kafka/dcp16@";};Client {com.sun.security.auth.module.Krb5LoginModule requireduseKeyTab=truestoreKey=trueuseTicketCache=falseserviceName=zookeeperkeyTab="/etc/security/keytabs/kafka.service.keytab"principal="kafka/dcp16@";};问题描述:[kafka@DCP16 bin]$ ./kafka-console-producer --broker-list DCP16:9092 --topic topicin050511 --producer.config ../etc/kafka/producer.propertiesmon.KafkaException: Failed to construct kafka producerat org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.KafkaProducer.<init>(KafkaProducer.java:335)at org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.KafkaProducer.<init>(KafkaProducer.java:188)at kafka.producer.NewShinyProducer.<init>(BaseProducer.scala:40)at kafka.tools.ConsoleProducer$.main(ConsoleProducer.scala:45)at kafka.tools.ConsoleProducer.main(ConsoleProducer.scala)Caused by: mon.KafkaException: ng.IllegalArgumentException: Conflicting serviceName values found in JAAS and Kafka configs value in JAAS file zookeeper, value in Kafka config kafkaat work.SaslChannelBuilder.configure(SaslChannelBuilder.java:86)at work.ChannelBuilders.create(ChannelBuilders.java:70)at org.apache.kafka.clients.ClientUtils.createChannelBuilder(ClientUtils.java:83)at org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.KafkaProducer.<init>(KafkaProducer.java:277)... 4 moreCaused by: ng.IllegalArgumentException: Conflicting serviceName values found in JAAS and Kafka configs value in JAAS file zookeeper, value in Kafka config kafkaat mon.security.kerberos.KerberosLogin.getServiceName(KerberosLogin.java:305)at mon.security.kerberos.KerberosLogin.configure(KerberosLogin.java:103)at mon.security.authenticator.LoginManager.<init>(LoginManager.java:45)at mon.security.authenticator.LoginManager.acquireLoginManager(LoginManager.java:68)at work.SaslChannelBuilder.configure(SaslChannelBuilder.java:78)... 7 more[kafka@DCP16 bin]$ ./kafka-console-producer --broker-list DCP16:9092 --topic topicin050511 --producer.config ../etc/kafka/producer.properties2.3 消费时报错: ERROR Unknown error when running consumer: (kafka.tools.ConsoleConsumer$)[root@DCP16 bin]# ./kafka-console-consumer --zookeeper dcp18:2181,dcp16:2181,dcp19:2181/kafkakerberos --from-beginning --topic topicout050511 --new-consumer --consumer.config ../etc/kafka/consumer.properties --bootstrap-server DCP16 [2017-05-07 22:24:37,479] ERROR Unknown error when running consumer: (kafka.tools.ConsoleConsumer$)mon.KafkaException: Failed to construct kafka consumerat org.apache.kafka.clients.consumer.KafkaConsumer.<init>(KafkaConsumer.java:702)at org.apache.kafka.clients.consumer.KafkaConsumer.<init>(KafkaConsumer.java:587)at org.apache.kafka.clients.consumer.KafkaConsumer.<init>(KafkaConsumer.java:569)at kafka.consumer.NewShinyConsumer.<init>(BaseConsumer.scala:53)at kafka.tools.ConsoleConsumer$.run(ConsoleConsumer.scala:64)at kafka.tools.ConsoleConsumer$.main(ConsoleConsumer.scala:51)at kafka.tools.ConsoleConsumer.main(ConsoleConsumer.scala)Caused by: mon.KafkaException: javax.security.auth.login.LoginException: Could not login: the client is being asked for a password, but the Kafka client code does not currently support obtaining a password from the user at work.SaslChannelBuilder.configure(SaslChannelBuilder.java:86)at work.ChannelBuilders.create(ChannelBuilders.java:70)at org.apache.kafka.clients.ClientUtils.createChannelBuilder(ClientUtils.java:83)at org.apache.kafka.clients.consumer.KafkaConsumer.<init>(KafkaConsumer.java:623)... 6 moreCaused by: javax.security.auth.login.LoginException: Could not login: the client is being asked for a password, but the Kafka client code does not currently support obtaining a password from the user. not available to garner authentication inform at com.sun.security.auth.module.Krb5LoginModule.promptForPass(Krb5LoginModule.java:899)at com.sun.security.auth.module.Krb5LoginModule.attemptAuthentication(Krb5LoginModule.java:719)at com.sun.security.auth.module.Krb5LoginModule.login(Krb5LoginModule.java:584)at sun.reflect.NativeMethodAccessorImpl.invoke0(Native Method)at sun.reflect.NativeMethodAccessorImpl.invoke(NativeMethodAccessorImpl.java:57)at sun.reflect.DelegatingMethodAccessorImpl.invoke(DelegatingMethodAccessorImpl.java:43)at ng.reflect.Method.invoke(Method.java:606)at javax.security.auth.login.LoginContext.invoke(LoginContext.java:762)at javax.security.auth.login.LoginContext.access$000(LoginContext.java:203)at javax.security.auth.login.LoginContext$4.run(LoginContext.java:690)at javax.security.auth.login.LoginContext$4.run(LoginContext.java:688)at java.security.AccessController.doPrivileged(Native Method)at javax.security.auth.login.LoginContext.invokePriv(LoginContext.java:687)at javax.security.auth.login.LoginContext.login(LoginContext.java:595)at mon.security.authenticator.AbstractLogin.login(AbstractLogin.java:69)at mon.security.kerberos.KerberosLogin.login(KerberosLogin.java:110)at mon.security.authenticator.LoginManager.<init>(LoginManager.java:46)at mon.security.authenticator.LoginManager.acquireLoginManager(LoginManager.java:68)at work.SaslChannelBuilder.configure(SaslChannelBuilder.java:78)衍⽣问题:kafka⽣产消息就会报错:[2017-05-07 23:17:16,240] ERROR Error when sending message to topic topicin050511 with key: null, value: 0 bytes with error: (org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.internals.ErrorLoggingCallback)mon.errors.TimeoutException: Failed to update metadata after 60000 ms.把KafkaClient更改为如下的配置,就可以了:KafkaClient {com.sun.security.auth.module.Krb5LoginModule requireduseTicketCache=true;};0x03消费者报错3.1 第⼀种错误:replication factor: 1 larger than available brokers: 0消费时报错:Error while executing topic command : replication factor: 1 larger than available brokers: 0解决办法:/confluent-3.0.0/bin 下重启daemon./kafka-server-stop -daemon ../etc/kafka/server.properties./kafka-server-start -daemon ../etc/kafka/server.properties然后zk重启;sh zkCli.sh -server ai186;/usr/hdp/2.4.2.0-258/zookeeper/bin/zkCli.sh --脚本的⽬录如果还报错,可以查看配置⽂件中下⾯的配置:zookeeper.connect=dcp18:2181/kafkakerberos; --是group名称3.2 第⼆种错误:TOPIC_AUTHORIZATION_FAILED./bin/kafka-console-consumer --zookeeper DCP185:2181,DCP186:2181,DCP187:2181/kafka --from-beginning --topic wangjuan_topic1 --new-consumer --consumer.config ./etc/kafka/consumer.properties --bootstrap-server DCP187:9092 [2017-03-02 13:44:38,398] WARN The configuration zookeeper.connection.timeout.ms = 6000 was supplied but isn't a known config. (org.apache.kafka.clients.consumer.ConsumerConfig)[2017-03-02 13:44:38,575] WARN Error while fetching metadata with correlation id 1 : {wangjuan_topic1=TOPIC_AUTHORIZATION_FAILED} (workClient)[2017-03-02 13:44:38,677] WARN Error while fetching metadata with correlation id 2 : {wangjuan_topic1=TOPIC_AUTHORIZATION_FAILED} (workClient)[2017-03-02 13:44:38,780] WARN Error while fetching metadata with correlation id 3 : {wangjuan_topic1=TOPIC_AUTHORIZATION_FAILED} (workClient)解决⽅法:配置⽂件中下⾯的参数中的User的U必须是⼤写;ers=User:kafka或者有可能是server.properties中的adver.listen的IP是不对的,有可能是代码中写死的IP;3.3 第三种错误的可能的解决⽅法:⽆法消费,则查看kafka的启动⽇志中的报错信息:⽇志⽂件的所属组不对,应该是hadoop;或者,查看kafka对应的zookeeper的配置后缀,是否已经更改,如果更改了,则topic需要重新⽣成才⾏;3.4 第四种错误:消费的tomcat报错[2017-04-01 06:37:21,823] [INFO] [Thread-5] [AbstractCoordinator.java line:542] Marking the coordinator DCP187:9092 (id: 2147483647 rack: null) dead for group test-consumer-group[2017-04-01 06:37:21,825] [WARN] [Thread-5] [ConsumerCoordinator.java line:476] Auto offset commit failed for group test-consumer-group: Commit offsets failed with retriable exception. You should retry committing offsets.更改代码中,tomcat的⼼跳超时时间如下:没有改之前的:;./webapps/web/WEB-INF/classes/com/ai/bdx/dcp/hadoop/service/impl/DCPKafkaConsumer.class;重启后,⽇志中显⽰:[2017-04-01 10:14:56,167] [INFO] [Thread-5] [AbstractCoordinator.java line:542] Marking the coordinator DCP187:9092 (id: 2147483647 rack: null) dead for group test-consumer-group[2017-04-01 10:14:56,286] [INFO] [Thread-5] [AbstractCoordinator.java line:505] Discovered coordinator DCP187:9092 (id: 2147483647 rack: null) for group test-consumer-group.0x04 创建topic时错误创建topic时报错:[2017-04-10 10:32:23,776] WARN SASL configuration failed: javax.security.auth.login.LoginException: Checksum failed Will continue connection to Zookeeper server without SASL authentication, if Zookeeper server allows it. (org.apache.zooke Exception in thread "main" org.I0Itec.zkclient.exception.ZkAuthFailedException: Authentication failureat org.I0Itec.zkclient.ZkClient.waitForKeeperState(ZkClient.java:946)at org.I0Itec.zkclient.ZkClient.waitUntilConnected(ZkClient.java:923)at org.I0Itec.zkclient.ZkClient.connect(ZkClient.java:1230)at org.I0Itec.zkclient.ZkClient.<init>(ZkClient.java:156)at org.I0Itec.zkclient.ZkClient.<init>(ZkClient.java:130)at kafka.utils.ZkUtils$.createZkClientAndConnection(ZkUtils.scala:75)at kafka.utils.ZkUtils$.apply(ZkUtils.scala:57)at kafka.admin.TopicCommand$.main(TopicCommand.scala:54)at kafka.admin.TopicCommand.main(TopicCommand.scala)问题定位:是jaas⽂件有问题:解决⽅法:server.properties⽂件中的er要和jaas⽂件中的keytab的principle⼀致;server.properties:ers=User:clientkafka_server_jaas.conf⽂件改为:KafkaServer {com.sun.security.auth.module.Krb5LoginModule requireduseKeyTab=truestoreKey=trueuseTicketCache=falseserviceName=kafkakeyTab="/data/data1/confluent-3.0.0/kafka.keytab"principal="kafka@";};KafkaClient {com.sun.security.auth.module.Krb5LoginModule requireduseKeyTab=truestoreKey=truekeyTab="/home/client/client.keytab"principal="client/DCP187@";};Client {com.sun.security.auth.module.Krb5LoginModule requireduseKeyTab=truestoreKey=trueuseTicketCache=falseserviceName=zookeeperkeyTab="/home/client/client.keytab"principal="client/DCP187@";};。

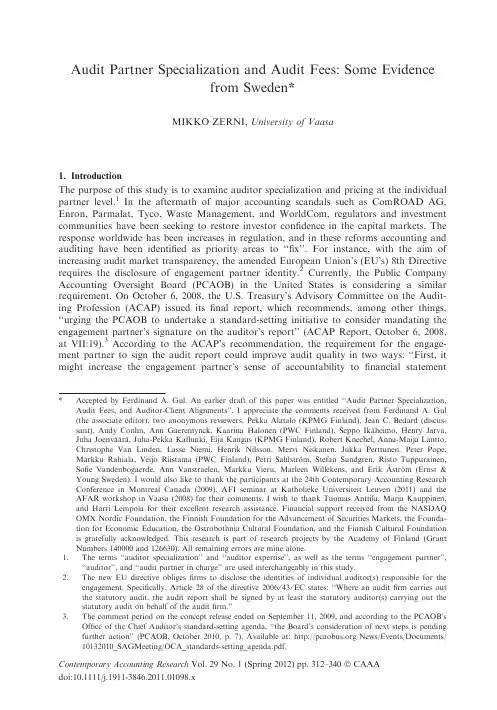

Audit Partner Specialization and Audit Fees:Some Evidencefrom Sweden*MIKKO ZERNI,University of Vaasa1.IntroductionThe purpose of this study is to examine auditor specialization and pricing at the individual partner level.1In the aftermath of major accounting scandals such as ComROAD AG, Enron,Parmalat,Tyco,Waste Management,and WorldCom,regulators and investment communities have been seeking to restore investor confidence in the capital markets.The response worldwide has been increases in regulation,and in these reforms accounting and auditing have been identified as priority areas to‘‘fix’’.For instance,with the aim of increasing audit market transparency,the amended European Union’s(EU’s)8th Directive requires the disclosure of engagement partner identity.2Currently,the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board(PCAOB)in the United States is considering a similar requirement.On October6,2008,the U.S.Treasury’s Advisory Committee on the Audit-ing Profession(ACAP)issued itsfinal report,which recommends,among other things,‘‘urging the PCAOB to undertake a standard-setting initiative to consider mandating the engagement partner’s signature on the auditor’s report’’(ACAP Report,October6,2008, at VII:19).3According to the ACAP’s recommendation,the requirement for the engage-ment partner to sign the audit report could improve audit quality in two ways:‘‘First,it might increase the engagement partner’s sense of accountability tofinancial statement *Accepted by Ferdinand A.Gul.An earlier draft of this paper was entitled‘‘Audit Partner Specialization, Audit Fees,and Auditor-Client Alignments’’.I appreciate the comments received from Ferdinand A.Gul (the associate editor),two anonymous reviewers,Pekka Alatalo(KPMG Finland),Jean C.Bedard(discus-sant),Andy Conlin,Ann Gaeremynck,Kaarina Halonen(PWC Finland),Seppo Ika heimo,Henry Jarva, Juha Joenva a ra,Juha-Pekka Kallunki,Eija Kangas(KPMG Finland),Robert Knechel,Anna-Maija Lantto, Christophe Van Linden,Lasse Niemi,Henrik Nilsson,Mervi Niskanen,Jukka Perttunen,Peter Pope, Markku Rahiala,Veijo Riistama(PWC Finland),Petri Sahlstro m,Stefan Sundgren,Risto Tuppurainen, Sofie Vandenbogaerde,Ann Vanstraelen,Markku Vieru,Marleen Willekens,and Erik A stro m(Ernst& Young Sweden).I would also like to thank the participants at the24th Contemporary Accounting Research Conference in Montreal Canada(2009),AFI seminar at Katholieke Universiteit Leuven(2011)and the AFAR workshop in Vaasa(2008)for their comments.I wish to thank Tuomas Anttila,Marja Kauppinen, and Harri Lempola for their excellent research assistance.Financial support received from the NASDAQ OMX Nordic Foundation,the Finnish Foundation for the Advancement of Securities Markets,the Founda-tion for Economic Education,the Ostrobothnia Cultural Foundation,and the Finnish Cultural Foundation is gratefully acknowledged.This research is part of research projects by the Academy of Finland(Grant Numbers140000and126630).All remaining errors are mine alone.1.The terms‘‘auditor specialization’’and‘‘auditor expertise’’,as well as the terms‘‘engagement partner’’,‘‘auditor’’,and‘‘audit partner in charge’’are used interchangeably in this study.2.The new EU directive obligesfirms to disclose the identities of individual auditor(s)responsible for theengagement.Specifically,Article28of the directive2006⁄43⁄EC states:‘‘Where an auditfirm carries out the statutory audit,the audit report shall be signed by at least the statutory auditor(s)carrying out the statutory audit on behalf of the auditfirm.’’3.The comment period on the concept release ended on September11,2009,and according to the PCAOB’sOffice of the Chief Auditor’s standard-setting agenda,‘‘the Board’s consideration of next steps is pending further action’’(PCAOB,October2010,p.7).Available at:/News/Events/Documents/ 10132010_SAGMeeting/OCA_standards-setting_agenda.pdf.Contemporary Accounting Research Vol.29No.1(Spring2012)pp.312–340ÓCAAAdoi:10.1111/j.1911-3846.2011.01098.xAudit Partner Specialization and Audit Fees313 users,which could lead him or her to exercise greater care in performing the audit. Second,it would increase transparency about who is responsible for performing the audit, which could provide useful information to investors and,in turn,provide an additional incentive tofirms to improve the quality of all of their engagement partners.’’Some have compared the initiative to thefinancial statement certification requirement by top manage-ment stipulated in Section302of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act,arguing that it should help focus engagement partners on their existing responsibilities(see,e.g.,Carcello,Bedard, and Hermanson2009:79).4Changes in legislation and initiatives requiring the disclosure of the identities of individ-ual auditors carrying out audits implicitly acknowledge that a public company audit involves a substantial amount of work by highly skilled individual practitioners exercising their own professional judgment.It is the lead engagement partners working in the city level audit offices who play a central role in planning and implementing the audit and ulti-mately in determining the appropriate type of audit report to be issued to the client(e.g., Ferguson,Francis,and Stokes2003).Consequently,the engagement partner may play an essential role in the(perceived)audit quality beyond auditfirm size and(industry)special-ization at the national and office level and should hence not be ignored.The level of audit effort and fees depends on the client’s agency-driven demand for external auditing and on supply-side factors,such as auditfirm size,auditor expertise and auditor-perceived risk factors(e.g.,DeFond1992;O’Keefe,Simunic,and Stein1994; Gul and Tsui1998;Bell,Landsman,and Shackelford2001;Johnstone and Bedard2001, 2003;Gul and Goodwin2010;Causholli,De Martinis,Hay,and Knechel2011).From the supply-side perspective,auditors are expected to respond to the higher probability of any irregularities or accounting misstatements by increasing audit effort and charging higher fees.For instance,Gul and Tsui(1998)adopted a supply-side perspective and found that higher inherent risks associated with free cashflows are associated with higher audit effort and higher consequent fees.From the demand-side perspective,the appointment of a higher-quality auditor can serve as a signal of an enhanced quality of financial disclosure,which will potentially lead to greater value for the audit client by reducing some agency costs.Firm insiders,especially those in the heart of monitoring function(e.g.,independent directors on the boards and audit committees),may be willing to increase audit coverage to create a positive perception about thefinancial reporting quality.The positive perception will possibly facilitate thefirm to attract investments and fund profitable projects and allowfirm insiders to protect their reputation capital,avoid legal liability,and promote shareholder interests.Consistent with the demand-side per-spective,several studies report evidence suggesting that outside directors who act dili-gently demand high quality audits and pay higher audit fees(e.g.,Carcello,Hermansson, Neal,and Riley2002;Abbott,Parker,Peters,and Raghunandan2003;Knechel and Willekens2006).Auditing is generally viewed as a differentiated service with substantial variation observed in audit(effort)fees,even after controlling for observable factors such asfirm size and complexity.This differentiation allows clients some choice over the level of audit scrutiny even within audits conducted by the same(tier)auditfirms.An important means 4.Recent empirical evidence supports the view that the Sarbanes-Oxley Act Section302chief executive offi-cer(CEO)and chieffinancial officer(CFO)certification requirement had a positive effect onfinancial reporting quality.For instance,Cohen,Krishnamoorthy,and Wright(2010)report that68percent of practicing auditors interviewed believe that the certification requirement has had a positive effect on the integrity offinancial reports.Moreover,to the extent that the disclosure of engagement partner identity will increase accountability,it may thereby improve audit decisions and judgments.In particular,some studies in the auditing context report evidence indicating that accountability reduces information process-ing biases,and increases consensus and self-insight(e.g.,Johnson and Kaplan1991;Kennedy1993).CAR Vol.29No.1(Spring2012)314Contemporary Accounting Researchof audit product differentiation is through investments in specialization(Simunic and Stein1987;Liu and Simunic2005).By specializing in certain industries,certain size groups,or companies with similar risk profiles,individual auditors may be able to differ-entiate their product from those of nonspecialist audit partners(Simunic and Stein1987; Liu and Simunic2005).The Swedish Code for Corporate Governance,for instance, implicitly recognizes auditor specialization in large public companies as one relevant piece of information when assessing the quality of external auditing.5Specifically,the Code rec-ommends that information on‘‘the audit services performed by the auditor or the auditor in charge in other large companies...and other information that may be important to shareholders in assessing the competence and independence of the auditor,or auditor in charge must be disclosed in a corporate governance report on company’s homepage’’(Ori-ginal Code Sections2.3.2and2.3.3).To justify their presence in the audit market and the potential fee premiums attached to their services,the client must perceive some benefit in hiring a specialist auditor.The premium may,for instance,be attributed to the signal value of hiring a specialist auditor or to the superior advisory or other services provided by that auditor(Titman and Trueman1986).Given that a demand exists for special-ist auditors,that demand gives those auditors a greater‘‘power’’in pricing relative to nonspecialists.This paper is motivated by the lack of archival research examining issues related to engagement partner specialization.In the present study,the use of Swedish data makes it possible to construct individual audit partner client portfolios because each audit report discloses the name of the audit engagement partner.Thus,information on the identity of the audit partner in charge is observable to users offinancial statements and thereby potentially affects market-assessed perception of ex ante audit rma-tion on the sizes and compositions of the Big4audit partner-specific client portfolios provides an interesting opportunity to contribute to a more thorough understanding of auditor specialization.More specifically,it is possible to examine whether the perceived audit quality is affected not only by the brand name of thefirm,but also by the charac-teristics and reputation of the engagement partner.In essence,if auditing expertise were wholly transferable and therefore uniformly distributed across audit partners within the firm,any clientfirm would be indifferent to having any audit partner within the Big4 auditors(within a particular Big4auditfirm⁄office)to conduct the audit.Additionally, there would be no a priori reason why clients would be willing to pay any audit partner related premiums.The empiricalfindings indicate systematic differences between audit partner clienteles, suggesting audit partner specialization in different industries and in different size groups. Thisfinding is consistent with Liu and Simunic2005,who argue that auditor specializa-tion could be a competitive response by either an auditfirm or an individual audit part-ner to induce efficient audits for different types of clients,thereby gaining a limited monopoly power(and earning rents)over the clients in which they specialize.Further-more,consistent with the view that there are returns on investing in specialization,analy-ses of audit fees indicate that both audit partner industry specialization and specialization in large public companies are recognized and valued byfinancial statement users and⁄or by corporate insiders,resulting in higher fees within these engagements.According to the empirical analyses,the highest fees are earned by engagement partners who are both 5.The Swedish Corporate Governance Board is responsible for promoting and developing the Code.On July1,2005,the Stockholm Stock Exchange began applying the Swedish Code of Corporate Governance.The Code applies to all Swedish companies listed at the Stockholm Stock Exchange and foreign companies that are listed at the same exchange and whose market capitalization exceeds SEK3billion.For more information,see http://www.corporategovernanceboard.se/.CAR Vol.29No.1(Spring2012)Audit Partner Specialization and Audit Fees315 industry and publicfirm specialists.The results may be interpreted to mean that the appointment of a specialist engagement partner is associated with higher(perceived)audit quality,thus justifying the fee premium.6Collectively,thefindings of this study support the view that clientfirms infer audit quality at least to some extent from the characteris-tics of the individual audit partner in charge.The remainder of the paper is organized as follows.Section2reviews the relevant lit-erature and describes some relevant features of the Swedish audit market.Section3pre-sents the hypothesis,and section4describes the data.Section5describes the methodology used,section6presents the empirical results,and section7concludes the study.2.Literature reviewNational versus local view of the auditor–client relationshipPrior audit research literature is dominated byfirm-wide analyses treating the whole accountingfirm as the focal point and investigating whether and how auditfirm char-acteristics,such as size and industry specialization at the nationalfirm level,affect the auditor–client relationship(e.g.,Simunic and Stein1987;Francis and Wilson1988;Bec-ker,DeFond,Jiambalvo,and Subramanyam1998;Francis and Krishnan1999).All these studies implicitly assume that through standardizedfirm-wide policies and knowl-edge sharing(e.g.,through training materials,industry-specific databases,internal benchmarks for best practices,audit system programs,and internal consultative prac-tices),all audits across practice offices and audit partners within an auditfirm are uniform.7However,in practice,it is the individual audit partners from city-level practice offices who are creating and taking care of the relationship,contracting with the client,adminis-tering the audit engagement,directing the audit effort,interpreting the audit evidence,and finally issuing the appropriate audit report(Ferguson et al.2003).Because of this decen-tralized organizational structure and because individual audit partners and their character-istics vary across engagements,a research approach allowing each individual partner to be a unique and relevant unit of analysis might be a more reasonable approach than assum-ing that all audits within an auditfirm are uniform.Consistent with this intuition,a growing number of recent audit studies have changed the direction from afirm-wide to an office-level view of auditfirms(e.g.,Reynolds and Francis2000;Ferguson et al.2003;Francis,Reichelt,and Wang2005;Francis and Yu 2009;Reichelt and Wang2010;Choi,Kim,Kim,and Zang,2010).The local stream of audit literature acknowledges the likelihood that part of an auditor’s expertise is uniquely held by individual professionals through their personal knowledge of clients and cannot be 6.From the risk-based audit supply view,an alternative explanation for the observed specialist audit partnerfee premium is that the clients of specialist audit partners are systematically riskier than the clients of non-specialists in dimensions other than those already controlled for in the empirical fee model(or in thefirst-stage selection model of the Heckman two-stage approach).Despite using a two-stage Heckman1978pro-cedure and including several audit risk-related control variables in the audit fee model,the empiricalfind-ings remain susceptible to the concern that some of the omitted risk factors recognized and priced by the specialist audit partners that simultaneously determine the alignment of audit partners with engagements would explain the outcome.7.Examples of the information technology systems used in knowledge sharing include KPMG’s KWorld TM,PriceWaterhouseCoopers’s TeamAsset TM and KnowledgeCurve TM,and Ernst&Young’s Knowledge-Web TM.See Vera-Munoz,Ho,and Chow2006for factors affecting knowledge sharing within interna-tional accountingfirms,and Banker,Chang,and Kao2002for a detailed description of an international accountingfirm’s implementation of audit software and groupware for knowledge sharing.CAR Vol.29No.1(Spring2012)316Contemporary Accounting Researchreadily captured and distributed by thefirm to other offices and clients(e.g.,Ferguson et al.2003).8The results of the empirical studies adopting a local perspective tend to provide a bet-ter understanding of the operations of a Big4auditfirm than do studies taking a national perspective.For instance,there is evidence that auditors’reputation for industry expertise is neither strictly national nor strictly local in character.Auditors who are both city and industry leaders are reported to earn fee premiums both in Australia and in the United States,suggesting that there is both a national and local office reputation effect in the pric-ing of industry expertise(Ferguson et al.2003;Francis et al.2005).Moreover,both these studiesfind thatfirm-level industry specialists alone do not earn statistically significant premiums.In another study,Reichelt and Wang(2010)use U.S.data and three proxies for audit quality(abnormal accruals,clientfirms’likelihood of meeting or beating ana-lysts’earnings forecasts by one penny per share,and the propensity to issue a going con-cern audit opinion)andfind evidence consistent with the view that audit quality is higher when the auditor is both a national and city-specific industry expert.Recent and concurrent studies have pushed the local analysis still one step further to the engagement partner level.A growing number of studies use engagement partner data (mainly from Australia and Taiwan)and examine issues such as the relationship between engagement partner tenure and audit quality,producing mixedfindings(e.g.,Carey and Simnett2006;Chen,Lin,and Lin2008;Chi,Huang,Liao,and Xie2009).In a recent study,Chin and Chi(2009)use a sample of listedfirms in Taiwan to investigate the associ-ation between auditor industry expertise and restatement likelihood at the partner level and at the auditfirm level simultaneously.Their evidence suggests that the differences in restatement likelihood due to industry expertise is mainly attributable to the partner-level experts rather than to thefirm-level experts.In summary,the recent empirical evidence suggests that auditor expertise has a strong local dimension.The central conceptual question in all the national versus local studies relates to the degree to which there is a transfer of expertise from office-based accounting professionals to other auditors and offices within thefirm(Ferguson et al.2003;Francis2004).There are several factors that may deter the transfer of expertise within organizations,including audit firms(see,e.g.,Szulanski1994,2000;Nonaka and Takeuchi1995).With respect to audit firms,Vera-Munoz et al.(2006)enumerate several reasons why it is difficult for partners to share knowledge with other partners.First,a considerable amount of knowledge in audit firms can be difficult to document or transfer.9Second,even if an auditfirm manages to 8.As noted by Francis2004,another reason for this development is that Big4market shares continue toexpand globally,leading to low power in research designs of studies comparing large and small auditors because there is such low variance in the experimental variable(i.e.,most observations are audited by large Big4auditors).For instance,according to a recent Government Accountability Office(GAO) report,in2006the largest fourfirms collected94percent of all audit fees paid by public companies.More-over,according to the same report,82percent of the Fortune1000companies saw their choice of auditors as limited to three or fewerfirms,and about60percent viewed competition in their audit market as insuf-ficient(GAO2008).9.According to Polanyi1966,knowledge comes in two types:explicit and tacit.The former is amenable tocodification,while the latter is anchored in individual personal beliefs,experiences,and values.For exam-ple,knowledge of generally accepted accounting principles(GAAP)with regard to fair value requirements is explicit knowledge,while an auditor’s insights as to how a client’s management develops fair value esti-mates and whether those estimates conform to GAAP represents tacit knowledge(Vera-Munoz et al.2006).Tacit knowledge is subconsciously understood and applied and is therefore not easily articulated (Polanyi1966).Prior studies further show that most of the knowledge in any organization,including an auditfirm,is tacit knowledge(Bonner2000;Knechel2000).Consequently,because differences in knowl-edge between individual auditors within afirm lie primarily in their respective tacit knowledge,which is not easily transferred,it is unlikely thatfirm-level practices completely smooth out the differences in the levels of individual audit partner expertise.CAR Vol.29No.1(Spring2012)Audit Partner Specialization and Audit Fees317 collect extensive databases and otherfirm-wide knowledge,individual auditors still need to use their own judgment in selecting and applying relevant pieces of information given the task at hand.Third,knowledge-sharing through information technology–based expert knowledge systems is not automatically embraced by everyone.Finally,evaluation appre-hension,performance-based compensation schemes and individual auditors’pursuit of per-sonal benefits and power may deter auditors from sharing what they know.In essence, holding on to information that other peers do not have may ceteris paribus offer competi-tive advantage against those peers,when auditors,like other rational players in the econ-omy,attempt to maximize their own(economic)interests.Collectively,factors identified above may partly explain the tendency of local audit studies to provide a better understand-ing of the auditor-client relationship thanfirm-wide analyses.Factors affecting expertiseThe Merriam-Webster dictionary defines an‘‘expert’’as having,involving,or displaying a special skill or knowledge derived from training or experience.The psychological literature on expertise has reported two importantfindings relevant to the present study.First, domain-specific knowledge is the essential determinant of expertise.Second,expert knowl-edge is gained through many years of on-the-job experience(e.g.,Chi,Glaser,and Rees 1982;Glaser and Chi1988;Glaser and Bassok1989;Lapre,Mukkerjee,and Van Was-senhove2000).In other words,intensive practice and the repetition of similar tasks are required to build expertise.When applied to auditing,thesefindings suggest that having serviced many similar clients in the past may help auditors to develop a specialized knowl-edge of what these clients do and the challenges and issues they face,thereby creating in-depth knowledge of specific types of clients,leading to higher-quality audits and higher fees in these engagements.Consequently,in the present study,the terms‘‘auditor special-ization’’and‘‘auditor expertise’’are used to refer to the extent of auditors’prior audit experience with similar clients,for instance,clientfirms belonging to the same industry or size group.In other words,it is assumed that specialization is needed to gain deep exper-tise.By specializing in certain industries,certain size groups,or companies with similar risk profiles,individual auditors may be able to develop and supply the differentiated ser-vice that clients demand and that competitorsfind difficult to duplicate(Simunic and Stein 1987;Liu and Simunic2005).Moreover,auditors will only develop a specialist reputation if this increases the credibility offinancial reporting and attracts clients.Auditor specialization and audit qualityFor a long time,standard-setters,quasi-regulatory bodies,and empirical audit research have suggested that differences in the level of auditor industry expertise may be one source of variation in audit quality(Hogan and Jeter1999;Gramling and Stone2001;GAO 2008).This body of literature assumes that audit issues are nested within an industry and that accountingfirms or individual auditors with many clients within a particular industry have more opportunities to acquire the kind of profound industry knowledge that leads to industry expertise.It is also argued that the heavy investments of industry specialist audi-tors in technologies,physical facilities,personnel,and organizational control systems pro-vide them with both incentives and abilities that make them more likely than nonspecialist auditors to detect and report any irregularities or misrepresentations in clientfirms’accounts(Simunic and Stein1987).Prior archival studies tend to document a positive association between auditors’indus-try expertise and the quality offinancial reporting(e.g.,Carcello and Nagy2002,2004; Balsam,Krishnan,and Yang2003;Krishnan2003,2005;Gul,Fung,and Jaggi2009).Spe-cifically,industry specialist auditors have been found to be less likely to be associated with Securities and Exchange Commission enforcement actions(Carcello and Nagy,2004).CAR Vol.29No.1(Spring2012)318Contemporary Accounting ResearchTheir clients are also reported to have a lower probability offinancial fraud(Carcello and Nagy2004,2004),smaller amounts of abnormal accruals,and higher earnings response coefficients(Balsam et al.2003;Krishnan2003,2005).In addition,a recent study by Gul et al.2009reports evidence suggesting that auditor industry specialization is likely to reduce the association between shorter auditor tenure and lower earnings quality.Behavioral research using experimental approaches has examined industry specializa-tion at the individual auditor level.The results of these studies suggest that an individual auditor’s expertise is tied not only to each individual professional and his or her deep per-sonal knowledge of clients but also to the innate abilities of each individual(e.g.,Bonner and Lewis1990;Libby and Tan1994;Owhoso,Messier,and Lynch2002).Overall,the results of studies on auditor specialization suggest that industry specialist auditors deliver higher-quality audits than do nonspecialists and that this difference in quality is also rec-ognized by the audit market.Even though the auditor specialization literature has focused almost entirely on indus-try specialization,it is plausible that there are also other types of auditor specialization besides industry specialization.Accordingly,an investigation of the(Swedish)homepages of the Big4firms reveals that each of thefirms has structured their national practices along both industry lines and client size.All have at least two business lines based on client size:small and medium-sized companies and large public⁄international companies. All fourfirms also market a wider variety of specialized expertise,such as specialization in owner-manager companies,family businesses,public sector organizations,and nonprofit organizations.Moreover,as noted already,the Swedish Code for Corporate Governance implicitly recognizes auditor specialization in working with different size groups by recom-mending the disclosure of‘‘the audit services performed by the auditor or the auditor in charge in other large companies’’,viewing this as a relevant piece of information for users offinancial statements.Performing audits of large,complex high-profile clients is likely to require auditor expertise widely different from that required for audits of smaller and simpler closely held clients.A public listing is an important part of auditor business risk(Johnstone and Bedard2003).Because companies listed on a stock exchange receive more media attention and therefore pose a higher litigation and reputational risk,they may require a specialist auditor(Johnstone and Bedard2003).Another clear distinction between audits of public and private companies relate tofinancial reporting standards.10In Swe-den,as in all EU member countries,publicly listed companies are required to follow IFRS standards in theirfinancial reporting.Whereas Swedish private companies are also allowed to follow IFRS standards in their consolidatedfinancial statements,they tend to follow national standards(Bokfo ringsna mndens Anvisningar),which include several significant simplifications compared to IFRS.Accordingly,in the present study,com-pany size and listing status in particular is used as a proxy for client complexity and risk profile.The aforementioned differences between audits of public and private companies make it more likely that client companies will value auditor specialization in particular size groups(i.e.,public versus privatefirms).They may also suggest that specialization in a certain size group will overlap somewhat with industry specialization.It appears intuitively more valuable for publicly listed client companies seeking a higher level of audit assurance to hire an engagement partner with relevant industry experience on other large companies with similarfinancial reporting requirements,rather than hire an engagement partner with industry experience only on smaller private companies.This potential overlap is further addressed in the empirical results section below.10.I wish to thank an anonymous reviewer for making this point.CAR Vol.29No.1(Spring2012)。

LTE切换及互操作优化技术手册2015年3月LTE切换及互操作优化技术手册目录1概述 (2)2 LTE切换原理 (2)2.1频内切换 (3)2。

1.1 eNodeB内切换 (3)2。

1。

2 基于X2接口的切换 (4)2。

1.3 基于S1接口的切换 (7)2.2频间切换 (9)3 LTE互操作原理 (9)3.1空闲态互操作原理 (9)3。

1。

1 LTE到2G/3G小区重选 (9)3。

1。

2 3G到LTE小区重选 (14)3.1.3 2G到LTE小区重选 (16)3。

2连接态PS业务互操作原理 (18)3.2。

1 LTE到3G的切换 (18)3。

2。

2 LTE到2G的切换 (22)3.2。

3 3G到LTE的切换 (24)3.2。

4 2G到LTE的切换 (28)3.2。

5 LTE到2G/3G的重定向 (30)3.2.6 2G/3G到LTE的重定向 (33)3.3 CSFB语音业务互操作原理 (34)3。

3。

1 CSFB的技术原理 (34)3。

3.2 CSFB的信令流程 (36)4 GUL互操作总体推荐策略 (40)4。

1空闲态 (41)4。

2 PS连接态 (41)4.3 CSFB语音业务 (42)4。

4邻区配置原则 (43)1概述本文主要从移动管理性出发,针对LTE的同频异频切换,及异系统的小区重选、重定向、切换进行分析,为LTE网络的切换、互操作优化提供方法与指导。

GUL(GSM/UMTS/LET)互操作是LTE商用后面临的重点难点问题。

特别是在LTE的布网初期,在LTE还没有达到整个网络全面覆盖的情况下,需要依赖现有的网络制式,实现多网协同,保证良好的用户感知.2 LTE切换原理当正在使用网络服务的用户从一个小区移动到另一个小区,或由于无线传输业务负荷量调整、激活操作维护、设备故障等原因,为了保证通信的连续性和服务的质量,系统要将该用户与原小区的通信链路转移到新的小区上,这个过程就是切换。

LTE的切换过程与WCDMA相同,包括测量、判决和执行三个过程,具体过程如下图所示:、RSRQ等图1 LTE系统中的切换过程基站根据不同的需要利用移动性管理算法给UE下发不同种类的测量任务,UE收到消息后,对测量对象实施测量,并用测量上报标准进行结果评估,当评估测量结果满足上报标准后向基站发送相应的测量报告,基站通过终端上报的测量报告决策是否执行切换。

稳定扩散权限设置方法一、背景介绍在当今数字化的社会中,信息的传播和共享变得越来越重要。

然而,在信息共享的过程中,我们也面临着信息泄露和隐私权保护的问题。

稳定扩散权限设置方法成为了一个备受关注的话题。

二、稳定扩散权限的概念稳定扩散权限,顾名思义,是指在信息共享过程中,确保信息只被授权的人所知晓,而未经授权的人无法获取相关信息的权限设置方法。

这种权限设置方法的出现,旨在保护信息共享者和信息接收者的利益,使得信息的传播更加稳定和安全。

三、稳定扩散权限的重要性1. 保护个人隐私权。

在信息共享的过程中,往往涉及到个人的隐私信息。

稳定扩散权限的设置能够有效地保护个人隐私权,避免个人信息被未经授权的人获取和利用。

2. 防止信息泄露。

对于一些机密信息或者商业机密,稳定扩散权限的设置能够有效地防止信息的泄露,保护企业和组织的利益。

3. 确保信息传播的稳定性。

通过合理的权限设置,可以确保信息的传播过程稳定可靠,不会因为误传或者非授权传播而导致信息的失真和错误传播。

四、稳定扩散权限的设置方法稳定扩散权限的设置方法可以从多个方面进行考虑和实践,具体包括以下几个方面:1. 用户身份认证和授权。

在信息共享的过程中,首先需要确保用户的身份是真实可靠的,然后再根据用户的身份进行权限的授权设置。

这一步骤可以通过密码认证、指纹识别等方式来进行。

2. 信息加密与解密。

对于需要保护的信息,可以采用加密的方式进行传输和存储,只有经过授权的人才能够进行解密查看。

这样可以有效地防止信息在传播过程中被非授权的人获取。

3. 合理的权限管理系统。

建立合理的权限管理系统,对不同用户设置不同的权限,确保信息的传播和使用是在授权范围内进行的。

五、稳定扩散权限设置方法的发展趋势随着信息技术的不断发展,稳定扩散权限的设置方法也在不断地更新和完善。

未来,我们可以期待以下几个方面的发展趋势:1. 个性化的权限设置。

随着大数据和人工智能技术的发展,未来可以实现个性化的权限设置,根据用户的需求和偏好来进行信息共享的权限设置。

nearby share原理什么是Nearby Share?Nearby Share是一种由谷歌推出的近场共享功能,旨在让Android设备用户能够快速、简便地共享文件和内容。

类似于苹果的AirDrop功能,Nearby Share利用蓝牙和Wi-Fi直接连接设备,而无需依赖互联网连接。

该功能在Android 11及更高版本中可用,并且可以跨设备、跨应用程序和跨平台使用。

实现Nearby Share的原理:1.蓝牙和Wi-Fi直连:Nearby Share利用蓝牙和Wi-Fi直接连接发送和接收设备。

当用户选择共享内容时,设备会在附近寻找其他可用的设备,并建立直连连接。

这种直连方式可以大大提高传输速度和稳定性。

2.选项优化:Nearby Share提供了三种传输选项:"所有人可见"、"联系人可见"和"关闭"。

用户可以根据个人偏好和隐私需求选择适当的选项。

该功能还允许用户将自己的设备设置为可见或隐身,以便决定是否接收其他设备的共享请求。

3.独立应用程序支持:Nearby Share并不局限于特定的应用程序或系统服务。

开发人员可以集成Nearby Share功能到他们的应用程序中,使其能够直接利用该功能来共享文件和内容。

这意味着用户可以通过Nearby Share与各种应用程序进行快速且安全的共享。

4.自动检测最佳传输介质:Nearby Share会自动判断哪种传输介质(蓝牙或Wi-Fi)对于特定的共享操作来说是最佳的。

例如,当共享较小的文件时,通常会使用蓝牙进行快速共享。

而对于大文件的传输,Nearby Share 则会自动使用Wi-Fi来提供更高的传输速度。

5.分块传输:为了确保稳定的传输以及在传输过程中最小化潜在的错误,Nearby Share会将文件分割为多个较小的块进行传输。

这也有助于提高共享文件的整体效率。

6.安全性和隐私保护:Nearby Share将安全性和隐私保护作为其设计和实施的重要原则。

Hadoop集群监控工具推荐与使用技巧随着大数据时代的到来,Hadoop已经成为了处理海量数据的主要工具之一。

然而,随着数据规模的不断增长,对Hadoop集群的监控变得愈发重要。

本文将介绍一些常用的Hadoop集群监控工具,并分享一些使用技巧,帮助读者更好地管理和监控自己的集群。

一、Hadoop集群监控工具推荐1. AmbariAmbari是一款由Apache开源的Hadoop集群管理工具,它提供了集群配置、部署、监控和管理等功能。

Ambari的优势在于它的用户友好性和可扩展性。

通过Ambari,用户可以方便地监控集群的状态、资源使用情况以及作业运行情况等。

2. GangliaGanglia是另一款常用的Hadoop集群监控工具,它主要用于实时监控集群的性能指标。

Ganglia通过采集集群各个节点的性能数据,并将其汇总展示在一个集中的监控平台上。

用户可以通过Ganglia监控集群的CPU利用率、内存使用情况、网络流量等指标,及时发现和解决潜在的性能问题。

3. NagiosNagios是一款广泛应用于各种IT系统的监控工具,它也可以用于监控Hadoop 集群。

Nagios提供了丰富的插件和扩展功能,可以监控集群的各个组件、服务和作业等。

通过配置Nagios,用户可以设置警报规则,及时获得集群的状态变化和异常情况。

二、Hadoop集群监控工具使用技巧1. 配置合适的监控指标在使用Hadoop集群监控工具时,需要根据自己的需求和集群的特点,选择合适的监控指标。

例如,如果集群的瓶颈在于网络带宽,那么监控网络流量指标将非常重要。

通过合适的监控指标,可以更准确地了解集群的状态和性能瓶颈,从而采取相应的优化措施。

2. 设置合理的警报规则监控工具的警报功能是非常重要的,它可以帮助用户及时发现和解决集群的异常情况。

然而,设置合理的警报规则并不是一件容易的事情。

过于敏感的警报规则可能导致频繁的误报,而过于迟钝的规则则可能延误问题的解决。

2024年电信5G基站建设理论考试题库(附答案)一、单选题1.在赛事保障值守过程中,出现网络突发故障,需要启用红黄蓝应急预案进行应急保障,确保快速处理和恢复。

红黄蓝应急预案的应急逻辑顺序为()A、网络安全->用户感知->网络性能B、网络性能->用户感知->网络安全C、用户感知->网络安全->网络性能D、用户感知->网络性能->网络安全参考答案:D2.2.1G规划,通过制定三步走共享实施方案,降配置,省TCO不包含哪项工作?A、低业务小区并网B、低业务小区关小区C、低业务小区拆小区D、高业务小区覆盖增强参考答案:D3.Type2-PDCCHmonsearchspaceset是用于()。

A、A)OthersysteminformationB、B)PagingC、C)RARD、D)RMSI参考答案:B4.SRIOV与OVS谁的转发性能高A、OVSB、SRIOVC、一样D、分场景,不一定参考答案:B5.用NR覆盖高层楼宇时,NR广播波束场景化建议配置成以下哪项?A、SCENARTO_1B、SCENARIO_0C、SCENARIO_13D、SCENARIO_6参考答案:C6.NR的频域资源分配使用哪种方式?A、仅在低层配置(非RRC)B、使用k0、k1和k2参数以实现分配灵活性C、使用SLIV控制符号级别的分配D、使用与LTE非常相似的RIV或bitmap分配参考答案:D7.SDN控制器可以使用下列哪种协议来发现SDN交换机之间的链路?A、HTTPB、BGPC、OSPFD、LLDP参考答案:D8.NR协议规定,采用Min-slot调度时,支持符号长度不包括哪种A、2B、4C、7D、9参考答案:D9.5G控制信道采用预定义的权值会生成以下那种波束?A、动态波束B、静态波束C、半静态波束D、宽波束参考答案:B10.TS38.211ONNR是下面哪个协议()A、PhysicalchannelsandmodulationB、NRandNG-RANOverallDescriptionC、RadioResourceControl(RRC)ProtocolD、BaseStation(BS)radiotransmissionandreception参考答案:A11.在NFV架构中,哪个组件完成网络服务(NS)的生命周期管理?A、NFV-OB、VNF-MC、VIMD、PIM参考答案:A12.5G需要满足1000倍的传输容量,则需要在多个维度进行提升,不包括下面哪个()A、更高的频谱效率B、更多的站点C、更多的频谱资源D、更低的传输时延参考答案:D13.GW-C和GW-U之间采用Sx接口,采用下列哪种协议A、GTP-CB、HTTPC、DiameterD、PFCP参考答案:D14.NR的频域资源分配使用哪种方式?A、仅在低层配置(非RRC)B、使用k0、k1和k2参数以实现分配灵活性C、使用SLIV控制符号级别的分配D、使用与LTE非常相似的RIV或bitmap分配参考答案:D15.下列哪个开源项目旨在将电信中心机房改造为下一代数据中心?A、OPNFVB、ONFC、CORDD、OpenDaylight参考答案:C16.NR中LongTruncated/LongBSR的MACCE包含几个bit()A、4B、8C、2D、6参考答案:B17.对于SCS120kHz,一个子帧内包含几个SlotA、1B、2C、4D、8参考答案:D18.SA组网中,UE做小区搜索的第一步是以下哪项?A、获取小区其他信息B、获取小区信号质量C、帧同步,获取PCI组编号D、半帧同步,获取PCI组内ID参考答案:D19.SA组网时,5G终端接入时需要选择融合网关,融合网关在DNS域名的'app-protocol'name添加什么后缀?A、+nc-nrB、+nr-ncC、+nr-nrD、+nc-nc参考答案:A20.NSAOption3x组网时,语音业务适合承载以下哪个承载上A、MCGBearB、SCGBearC、MCGSplitBearD、SCGSplitBear参考答案:A21.5G需要满足1000倍的传输容量,则需要在多个维度进行提升,不包括下面哪个()A、更高的频谱效率B、更多的站点C、更多的频谱资源D、更低的传输时延参考答案:D22.以SCS30KHz,子帧配比7:3为例,1s内调度次数多少次,其中下行多少次。

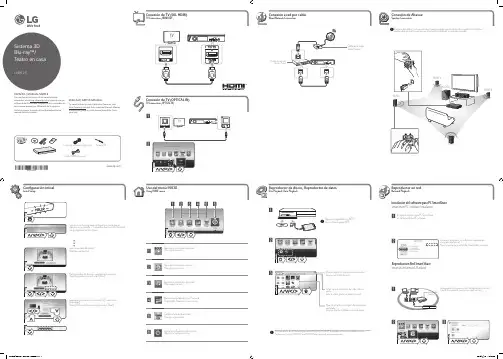

Reproduce contenidos de vídeo. /Plays video content.Reproduce contenidos de foto. /Plays photo content.Uso del menú INICIOUsing HOME menuEn la mayoría de los CD de audio y los discos BD-ROM y DVD-ROM, la reproducción se inicia automáticamente. /For the most Audio CD, BD-ROM and DVD-ROM discs, playback starts automatically.Reproducción Red Smart Share SmartShare Network PlaybackEnrutador RouterCENTERREAR RREAR LWOOFERa b c d e f• Si usa esta unidad con MUSIC ow, al menos una unidad debe ser conectada por cable LAN, paramás detalles de uso con MUSIC ow, consulte el manual de usuario de MUSIC If you use this unit with MUSIC ow, at least one unit should be connected by LAN cable. For more detail for use with MUSIC ow, refer to the MUSIC • Se recomienda conectar hasta 4 altavoces para una reproducción suave. / It is recommended to connect up to 4 speakers for smooth playback. • Al activar el modo de sonido privado, esta función no está disponible. / When you perform private sound mode, this function is unavailable. • Esta función está disponible sólo para contenidos de audio. / This function is available for only audio contents.Enrutador RouterMUSIC MUSIC MU GAntes de actualizar el software, la unidad debe estar conectada a la red doméstica. /Before updating software, the unit should be connected to your home network.,Descargue la aplicación “LG AV Remote” en iTunes o Google Play Store. /Download “LG AV Remote” on the iTunes store or Google Play Store.No todos los modos son compatibles con el sonido privado y el pareo de varios equipos podría Not all modes support sound privacy and pairing multiple devices is not available. ow, el modo de sonido privado no está disponible. / ow, private sound mode is unavailable.。

云计算HCIP模考试题(含参考答案)一、单选题(共52题,每题1分,共52分)1.FusionAccess 组件 WI 实现的主要功能是?A、提供最终用户的接入界面入口B、桌面接入登录负载均衡C、桌面接入的协议网关,内外网隔离、传输加密D、与虚拟机中的 HDA 进行交互,收集 HDA 上报的虚拟机状态及接入状态正确答案:A2.某企业准备上线华为桌面云系统,该企业对数据安全性要求高,现对用户虚拟机进行整机备份,以下哪个是不需要考虑的事项?A、备份软件:优秀的备份软件包括加速备份、自动操作、灾难恢复等特殊功能,对于安全有效的数据备份是非常重要的。

B、备份网络:备份网络可以选择 SAN,也可以选择 LAN,它是数据传输的通道,数据备份的效率高低与备份网络有密切关系。

C、备份介质:介质是数据的载体,它的质量一定要有保证,使用质量不过关的介质无疑是拿企业的数据在冒险。

D、备份的用户数据类型:用户数据有文档、视频等类型,不同的数据类型采用的备份方案也是不一样的,切勿用备份文档的方式来备份视频。

正确答案:D3.DNS 域名的层次结构是?A、顶级域-二级域-子域-主机B、根域-顶级域-二级域-子域-主机C、根域-顶级域-二级域-三级域-子域-主机D、根域-二级域-子域-主机正确答案:B4.FusionCompute 上,DP M 功能可用的前提是配置了单选主机的 BMC 信息。

A、TRUEB、FALSE正确答案:A5.在 FusionCompute 中,以下关于分布式虚拟交换机特性的描述,错误的是哪一项?A、每个 VM 可以具有多个 vNIC 接口,每个 vNIC 可以加入分布式交换机的多个端口组B、每个分布式交换机可配置多个端口组,每个端口组具有各自的属性C、用户可以配置多个分布式交换机,每个分布式交换机可以覆盖集群中的多个 CNA 节点D、每个分布式交换机可以配置一个上行链路组,用于 VM 对外的通信正确答案:A6.在 FusionAccess 中,当虚拟机的业务平面与 TC 网络平面不通时,虚拟机需添加除业务平面网卡和管理平面网卡外,与 TC 网络平面互通的第三张网卡A、TRUEB、FALSE正确答案:A7.在FusionCompute 中,三台虚拟机共用一个CPU 线程,主频为2.8GHz。

软件安装软件安装主要包括MasterServer、MediaServer、软件的安装。

在备份系统中,选择hp做为MasterServer,同时充当MediaServer的角色。

为便于管理,确定MasterServer作备份系统的Global Database Host,用于存放所有的配置和备份信息。

下面逐一介绍每一种软件的安装过程,软件安装列表见附件三。

2.4.1 NetBackup DataCenter MasterServer Installition安装前作如下准备工作,在MediaServer安装时也要作同样的准备:·连接硬件所有MediaServer/MasterServer以及带库、磁带机均连接到一台SAN光纤交换机。

·硬件识别在安装软件之前,要保证系统能够识别磁带机和机械手(只需MasterServer识别机械手)#ioscan –fnC tape·系统空间安装MasterServer之前,确保系统空间大小:RAM ≥512Mb安装目录可用空间≥64Mb/tmp可用空间≥32Mb·系统配置在备份环境中每台主机都要修改/etc/hosts文件,提供hostname/ip的解析。

在MasterServer端的/etc/hosts文件中增加如下内容:安装步骤如下:step1: pfs_mountd &pfsd 6&pfs_mount -o xlat=unix /dev/dsk/c3t2d0 /cdromstep2:切换到光盘目录#cd /cdromstep3:执行安装脚本#./installVERITAS Installation ScriptCopyright 1993 - 2002 VERITAS Software Corporation, All Rights Reserved.Installation Options1 NetBackup2 NetBackup Client Software3 NetBackup Client Java Softwareq To quit from this scriptChoose an option [default: q]: 1/*选则1,安装Server,同时也安装mediaserver 软件The NetBackup and Media Manager software is built for use on hp hardware.Do you want to install NetBackup and Media Manager files? (y/n) [y] yNetBackup is normally installed in /usr/openv/netbackup.Is it OK to install in /usr/openv/netbackup? (y/n) [y] y/*确定Netbackup安装目录Media Manager is normally installed in /usr/openv/volmgr.Is it OK to install in /usr/openv/volmgr? (y/n) [y] y/*确定MediaManager安装目录The hp clients will be loaded.Do you want to load any other NetBackup clients onto the server? (y/n) [y] n/*确定是否安装其他client,server本身已包含client软件,所以选择“n”……Enter license key: /*输入NetBackup DataCenter Base license AJX6-OPWD-IC6K-3N36-383P-NCNP-PNNR-PPP:NetBackup DataCenter Base product with the following features enabled: Core Frozen Image ServicesOpen Transaction Managerhas been registered.All additional keys should be added at this time.Do you want to add additional license keys now? (y/n) [y] y /*输入其他相关license,也可在安装完软件后再输入其他licenseLicense Key Utility-------------------A) Add a License KeyD) Delete a License KeyF) List Active License KeysL) List Registered License KeysH) Helpq) Quit License Key UtilityEnter a letter:Installing NetBackup DataCenter version: 4.5GAIs backupserver the master server? (y/n) [y] y /*设置主机backupserver作masterserver Do you have any media (slave) servers? (y/n) [n] y/*设置其他主机作mediaserver Enter the fully qualified name of a media (slave) server (q to quit)? SUNV880_AEnter the fully qualified name of a media (slave) server (q to quit)? SUNV880_B Enter the fully qualified name of a media (slave) server (q to quit)? qChecking for a bpcd entry in /etc/inetd.conf: Adding bpcd entry.Original /etc/inetd.conf saved as /etc/inetd.conf.NBU_061103.10:25:08.Checking for a vnetd entry in /etc/inetd.conf: Adding vnetd entry.Checking for a vopied entry in /etc/inetd.conf: Adding vopied entry.Checking for a bpjava-msvc entry in /etc/inetd.conf: Adding bpjava-msvc entry.Checking /etc/services for the needed NetBackup and Media Manager services.Copying original /etc/services file to /etc/services.NBU_061103.10:31:32/etc/services to update NetBackup and Media Manager services./etc/services will be updated to add the following entries for NetBackup/Media Manager.bprd 13720/tcp bprdbpcd 13782/tcp bpcdbpdbm 13721/tcp bpdbmvnetd 13724/tcp vnetdvopied 13783/tcp vopiedbpjobd 13723/tcp bpjobdnbdbd 13784/tcp nbdbdvisd 9284/tcp visdbpjava-msvc 13722/tcp bpjava-msvcvmd 13701/tcp vmdacsd 13702/tcp acsdtl8cd 13705/tcp tl8cdtldcd 13711/tcp tldcdts8d 13709/tcp ts8dodld 13706/tcp odldtl4d 13713/tcp tl4dtsdd 13714/tcp tsddtshd 13715/tcp tshdtlmd 13716/tcp tlmdtlhcd 13717/tcp tlhcdlmfcd 13718/tcp lmfcdrsmd 13719/tcp rsmdTo change these entries modify the file /tmp/services.ov_edited.24848and enter <RETURN> when ready to continue:/etc/services has been updated to contain NetBackup and Media Manager services.To make NetBackup and Media Manager start up automatically when the system is restarted, the rc.veritas.aix script found in /usr/openv/netbackup/bin/goodies has been placed in the /etc directory, you must modify /etc/inittab to include it.……Enter which host will store global device information.(default: backupserver): backupserver /*设置masterserver 作全局设备信息中心To be able to install the client software the NetBackupprocesses need to be started. Do you want to start theNetBackup processes so client software can be installed? (y/n) [y] yStarting the NetBackup database manager process (bpdbm)./*启动bpdbm进程以装载client软件Do you want to create policy and schedule examples that you can view or usewhen you are configuring your own policies and schedules? (y/n) [y]n/*确定是否安装策略模板Client database indexing reduces the search time when restoringclient files, but it takes about 2% more disk space.Do you want to index the client database files? (y/n) [y] y/*确定是否采用client index 文件The default index level is 9 levels. Use the default? (y/n) [y] y /*确定 client index levelRunning index_clients process in background mode.Output from the process will be written to /tmp/index_clients.output.Do you want to start the Media Manager device daemon processes? (y/n) [y] y Starting the Media Manager device daemon processes./*确定是否启动MediaManager 进程Do you want to start the NetBackup bprd process sobackups and restores can be initiated? (y/n) [y] yStarting the NetBackup request daemon process (bprd)./*确定是否启动Netbackup 监听进程Done executing NB.instStep4 :确认安装成功#/usr/openv/netbackup/bin/goodies/bp.kill_all关闭所有已启动的NBU进程#/usr/openv/netbackup/bin/goodies/netbackup start启动NBU进程#/usr/openv/netbackup/bin/bpps –a查看NBU进程#/usr/openv/netbackup/bin/jnbSA&启动NBU的java管理界面至此,MasterServer软件安装完毕。

存储HCIP测试题+参考答案一、单选题(共38题,每题1分,共38分)1.下面应用场景不属于 oceanstor 存储典型应用场景的时哪个?A、自动分级存储应用B、容灾应用C、高密度虚拟机应用D、容量需求为 EB 级别以上的多媒体应用正确答案:D2.在 HyperMetro 双活数据中心方案中,假如某阵列成员 LUN 出现坏块,以下说法不正确的是哪一项?A、当在读取该阵列本地 LUN 时,读取到坏块后,如果错误不可以修复,则系统会根据远端阵列 LUN 的数据进行修复。

B、当在读取该阵列本地 LUN 时,读取到坏块后,如果是不可以修复的错误,则返回主机读错误的信息。

C、当在读取该阵列本地 LUN 时,读取到坏块后,如果是可以修复的错误,将读数据返回主机,确保主机响应的快速返回。

D、当进行坏块修复时,首先要申请读权限,并确认双活 Pair 的本地读权限。

正确答案:B3.华为 Oceanstor 9000 存储系统采用分层安全维护,不属于应用层安全内容的是哪一项?A、活动记录B、密码系统C、授权和鉴权机制D、使用 SSH/SFTP 方法来规避不安全的网络通信正确答案:D4.对于华为 Oceanstor 9000 系统的数据保护功能的描述,以下哪个选项是不正确的?A、Oceanstor 9000 通过 ErasureCode 实现数据的 N+M 冗余存储B、Oceanstor 9000 通过镜像方式实现元数据的冗余存储C、启用物理分域后,单个域内的硬盘或节点故障,将会导致其他域的数据可靠性降级或失效D、保护级别为 N+ 1 时,集群所需要最少节点数目为 3正确答案:C5.在 Simpana 备份软件中,有关增量备份说法正确的是哪一项?A、自从上次备份后变化的数据作备份B、自从上次全备份后变化的数据作备份C、所有数据的完整备份D、初始备份数据之后所有数据的备份正确答案:A6.华为容灾方案中,关于同步远程复制顺序的描述正确的是:1 主存储阵列写 I/O 数据到主 LUN,并发送 IO 到从 LUN2 主机发送 IO 到主存储阵列。

net share 基本语法net share命令的基本语法如下:net share [sharename] [/DELETE]net share [sharename] [/UNLIMITED]net share [sharename] [/GRANT:user,[READ | CHANGE | FULL]] net share [sharename] [/USERS:number | /UNLIMITED]net share [sharename] [/REMARK:"text"]net share [sharename] [password:[password | *]]net share [sharename] [path:pathname]net share [sharename] [/USERS:number | /UNLIMITED][/REMARK:"text"] [/CACHE:Manual | Documents| Programs | BranchCache | None | Auto | Unknown]其中,[sharename]表示共享资源的名称。

后面的方括号内的内容为可选参数,包括:- /DELETE:删除指定的共享资源。

- /UNLIMITED:指定共享资源中并发连接的数量没有限制。

- /GRANT:user,[READ | CHANGE | FULL]:授予指定用户对共享资源的访问权限。

可选的权限包括读取(READ)、修改(CHANGE)和完全控制(FULL)。

- /USERS:number:指定允许连接到共享资源的并发用户数量。

如果设置为0,表示禁止任何用户连接。

- /REMARK:"text":为共享资源添加注释。

- password:[password | *]:指定对共享资源的访问密码。

可以明文输入密码,或者使用*代替,表示提示用户输入密码。

存储HCIP试题一、单选题(共40题,每题1分,共40分)1、与普通文件备份相比,在部署 VMware 备份时需要多部署的组件是:A、MAB、CAC、VSAD、CS正确答案:C2、客户提出了 RPO=0 且 RTO=0 的要求,同事选择了主备同步远程复制容灾方案,该方案:A、不能达到客户要求 RPO>0 且 RTO>0。

B、能达到客户要求。

C、不能达到客户要求,RTO>0D、不能达到客户要求 RPO>0正确答案:C3、做影响华为 Oceanstor 9000 客户端性能的因素的分析和调整时,包含的步骤有: a - 检查调整外部干扰因素 B - 查看性能监控工具的性能指标C - 检查调整系统配置正确的顺序应该是哪一项?A、acbabB、abcbaC、bcbabD、babcb正确答案:D4、某企业需要对其即时交易业务提供持续数据保护,因此对该业务数据LUN 创建了定时 HyperCDP 计划,以下哪项配置能尽可能缩短 RPO()A、设置 HyperCDP 的“保留个数”为 60000B、设置定时计划的“固定周期”为 3 秒C、在每天指定的时间点创建 HyperCDPD、创建多个 HyperCDP 备份正确答案:B5、华为容灾解决方案中,以下哪种距离可以选择同步远程复制技术?A、≤1000kmB、≤900kmC、≤100kmD、≤600km正确答案:C6、以下属于非结构化数据应用的是:A、企业财务系统B、医疗 HIS 数据库C、企业 ERPD、教育视频点播正确答案:D7、关于华为分布式存储多级缓存技术读缓存的过程,优先从下列哪项读取命中()A、Memory Write CacheB、SSD Read CacheC、Memory Read CacheD、SSD Write Cache正确答案:C8、以下关于 InfiniBand 技术的描述错误的是哪一项?A、InfiniBand 技术将被广泛推广于 Internet 网络的连接B、InfiniBand 技术具有高带宽、低时延、系统扩展性好的优点C、交换机是 InfiniBand 结构中的基本组件D、InfiniBand 技术常被应用于服务器与服务器之间的连接正确答案:A9、某跨国企业业务庞大,客户业务数据分散在多个地点,各地点之间距离大于 1000 km。

sharenothing架构原理ShareNothing架构是一种分布式系统架构,它的核心思想是将系统中的各个组件分离开来,使得它们之间没有任何共享资源,从而避免了共享资源带来的竞争和冲突,提高了系统的可靠性和可扩展性。

在ShareNothing架构中,每个组件都是独立的,它们之间通过消息传递来进行通信,而不是通过共享内存或共享数据库等方式。

这样做的好处是,每个组件都可以独立地进行扩展和部署,而不会影响到其他组件的运行。

同时,由于没有共享资源,也就避免了共享资源带来的竞争和冲突,从而提高了系统的可靠性和可用性。

ShareNothing架构的实现方式有很多种,其中比较常见的是基于消息队列的架构。

在这种架构中,每个组件都有自己的消息队列,它们之间通过消息队列来进行通信。

当一个组件需要向另一个组件发送消息时,它将消息发送到目标组件的消息队列中,目标组件再从自己的消息队列中读取消息进行处理。

这种方式可以有效地避免共享资源带来的竞争和冲突,同时也可以提高系统的可扩展性和可靠性。

除了基于消息队列的架构,还有一些其他的实现方式,比如基于Actor 模型的架构、基于微服务的架构等等。

无论采用哪种实现方式,ShareNothing架构都具有以下几个优点:1. 高可靠性:由于各个组件之间没有共享资源,因此避免了共享资源带来的竞争和冲突,从而提高了系统的可靠性和可用性。

2. 高可扩展性:由于每个组件都是独立的,它们之间没有任何依赖关系,因此可以很容易地进行扩展和部署,从而提高了系统的可扩展性。

3. 易于维护:由于各个组件之间没有共享资源,因此每个组件都可以独立地进行维护和升级,而不会影响到其他组件的运行。

总之,ShareNothing架构是一种非常优秀的分布式系统架构,它可以有效地提高系统的可靠性、可扩展性和可维护性,是现代分布式系统设计中不可或缺的一部分。