Corpus linguistics and language acquisition

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:133.36 KB

- 文档页数:29

Language and CognitionCognitive LinguisticsWhat Is Cognitive Linguistics?Cognitive linguistics is a newly established approach to the study of language that emerged in the 1970s. It is based on human experiences of the world and the way they perceive and conceptualize the world.Main Points in Cognitive LinguisticsConstrual and Construal OperationsCategorizationImage SchemasMetaphorMetonymyBlending TheoryConstrual and Construal OperationsConstrual is the ability to conceive and portray the same situation in alternate ways through specificity, different mental scanning, directionality, vantage point, figure-ground segregation, etc.Attention/ SalienceJudgment/ComparisonPerspective/SituatednessConstrual and Construal Operations : Attention/ SalienceThe operation in salience have to do with our direction of attention towards sth. that is salient to us.In cognition, we direct our attention to the activation of conceptual structures.We use certain linguistic expressions to provoke certain patterns of activation.Construal and Construal Operations : Judgment/ComparisonThe construal operations of judgment/ comparison have to do with judging sth. by comparing it to sth. else.The figure-ground alignment apply to space, with the ground as the prepositional object and the preposition expressing the spatial relational configuration.Static and dynamic figure/ groundTrajector for a moving figureLandmark for the ground of a moving figureCategorizationCategorization is the process of classifying our experiences into different categories based on commonalities and differences. There are three levels in categories.Basic levelSuper-ordinate levelSubordinate levelMetaphorMetaphor involves the comparison of two concepts in that one is constructed in terms of another. It is often described in terms of a target domain and a source domain. Lakoff and John classify conceptual metaphors into three categoriesThree Categories of MetaphorOntological metaphorsStructural metaphorsOrientational metaphorsThree Categories of MetaphorOntological metaphorsOntological metaphors means that human experiences with physical objects provide the basis for ways of viewing events, activities, emotions, ideas, etc. as entities and substances.Three Categories of MetaphorStructural metaphorsStructural metaphors allow us to go beyond orientation and referring and give us the possibility to structure one concept according to another.Three Categories of MetaphorOrientational metaphorsOrientational metaphors give a concept a spatial orientationMetonymyMetonymy is defined as a cognitive process in which the vehicle provides mental access to the target within the same domainTwo Conceptual ConfigurationsWhole ICM and its part(s)Parts of an ICMMetonymy— Whole ICM and its part(s)Thing-and-Part ICMScale ICMConstitution ICMEvent ICMCategory-and-Member ICMCategory-and-Property ICMReduction ICMMetonymy— Parts of an ICMAction ICMPerception ICMCausation ICMProduction ICMControl ICMPossession ICMContainment ICMLocation ICMSign and Reference ICMsModification ICMWhat Is Cognitive Linguistics? Blending TheoryFauconnier and Turner propose and discuss blending or integration theory, a cognitive operation whereby elements of two or more “mental spaces” are integrated via projection into new, blended space which has its unique structure. Conditions are needed when two input spaces I1 and I2 are blended:Cross-Space MappingGeneric SpaceBlendEmergent StructureWhat Is Cognitive Linguistics? Image SchemasImage schema is a recurring, dynamic pattern of our perceptual interactions and motor programs that gives coherence and structure to our experience.What Is Cognitive Linguistics? Image SchemasA center-periphery schemaA containment schemaA cycle schemaA force schemaA link schemaA part-whole schemaA path schemaA scale schemaA verticality schema类属空间输入空间1 输入空间2合成空间施事经历者锋利的刀具工作场所程序(目标、方式)角色:外科医生(外科医生身份)角色:病人(病人身份)手术刀手术室目标:康复方式:手术角色:屠夫角色:商品(动物)屠刀屠宰场目标:切肉方式:屠宰外科医生身份病人身份切肉手术刀手术室目标:康复方式:屠宰不称职Chapter nguage and CognitionWhat Is Cognition?What Is Psycholinguistics?What Is Cognitive Linguistics?What Is Cognition?DefinitionIn psychology, the term cognition is used to refer to the mental process of an individual, with particular relation to a view that argues that the mind had internal states and can be understood in terms of in formation processing, especially when a lot of abstraction or concretization is involved, or processes such as involving knowledge, expertise or learning at work.Another definition is the mental process of faculty of knowing, including aspects such as awareness, perception, reasoning and judgment.What Is Cognition?Three ApproachesThe formal approachIt basically addresses the structural patterns exhibited by the overt aspect of linguistic forms, abstracted away from or regarded as autonomous from any associated meaning.The psychological approachIt looks at language from the perspective of relatively general cognitive systems ranging from perception, memory, and attention to reasoning.The conceptual approach.It is concerned with the patterns in which and the processes by which conceptual content is organized in language. What Is Psycholinguistics?Psycholinguistics is an interdisciplinary study , it usually studies the psychological states and mental activity associated with the use of language.Text book P130-131: acquisition, comprehension, production, disorders, language and thought, neurocognition. Two Questions Concerned in PsycholinguisticsWhat knowledge of language is needed for us to use language?Tacit knowledge and explicit knowledgeLanguage knowledgeSemantics, syntax, phonology, pragmaticsWhat cognitive processes are involved in the ordinary use of language?The Information Processing Systemsensory storesTake in sensory stimuli for a brief time, in a raw, unanalyzed form .short-term memory/ working memoryHas both storage and processing functions.Permanent memoryHold the knowledge of the world. This includes general knowledge and personal experience.What Is Psycholinguistics?It is customary to distinguish six subjects of research within psycholinguistics:acquisition, comprehension, production, disorders, language and thought, neurocognition.Language AcquisitionHolophrastic stageTwo-word stageStage of three-word utterancesFluent grammatical conversation stageLanguage Acquisition :Holophrastic stageTwo main features of lexical development in early language acquisition:Most of their early words refer to concrete aspects of the immediate environment.Text book p. 132Children at this stage also tend to use single words to express larger chunks of meaning that mature speakers would express in a phrase or sentence.Text Book P 132Language Acquisition :Two-word stageChildren begin to put words together in systematic ways (primitive syntax begins), preferring some words to others and some orders to others.Children know more than they are able to express.Language Acquisition :Three-word StageChildren produce strings / three-word utterance containing all of its components in the correct order.Language Acquisition :Fluent grammatical conversation stageIt is between the late tow-word and mid-three-word stage.Three-year olds obey grammatical rules a majority of the time.Inflections and function words are more often used by Three-year olds than omitted in earlier sentences.Except for constructions that are rare, all parts of all language are acquired before the child turns four.Language ComprehensionThree Levels of speech processingWord recognitionComprehension of sentencesComprehension of textLanguage ComprehensionThree Levels of speech processingDiscriminate auditory signals from other sensory signals and determine that the stimulus is something that we have heard.identify the peculiar properties that qualify it as speech.recognizing it as the meaningful speech of a particular language.Word recognitionThe perception of spoken wordsCohort modelInteractive modelRace modelPre-lexical routeLexical routeThe perception of printed wordsThe perception of spoken wordsCohort modelDefinition: Cohort model is a model of auditory word recognition in which listeners are assumed to develop a group of candidates, a word initial cohort, and then determine which member of that cohort corresponds to the presented word.Two distinct aspects of spoken word recognitionRecognize words very rapidlyBe sensitive to the recognition pointCohort model—Three stages in Spoken word recognitionoccurs in on the basis of an acoustic-phonetic analysis of the input, a set of lexical candidates is activated. This set is referred to as the word initial cohort.one member of the cohort is selected for further analysis.Elimination takes place in two ways:Context and phonological informationthe selected lexical item is integrated into the ongoing semantic and syntactic context.The perception of spoken wordsCohort modelInteractive model (text book p136)Race model (text book p136)Pre-lexical routeLexical routeThe perception of printed words:Levels of written language processingFeature level: Stimulus is represented in terms of physical features that comprise a letter of the alphabet.Letter level: the visual stimulus is represented more abstractly .An array of features and letters is recognized as familiar word.The perception of printed words:Questions about orthography-to-phonologyHow linguistic structure is derived from printLexical routeNon-lexical routeConnectionist modelComprehension of sentencesStructural factors in comprehensionLexical factors in comprehensionSerial models and parallel modelsStructural factors in comprehensionDefinition:Interpreting sentence comprehension according to the grammatical constraints.Parsing strategiesLate closure strategyAttach new items to the current constituent.Minimal attachment strategyAttach new items into the phrase marker being constructed using the fewest syntactic nodesComprehension of sentencesStructural factors in comprehensionLexical factors in comprehensionSerial models and parallel modelsComprehension of Text/DiscourseLocal discourse structurethe relationships between individual sentences in the discourse.Global discourse structureIn order to understand the text, our general knowledge is connected to the text.Language ProductionAccess to wordsGeneration of sentencesWritten language productionAccess to wordsSpreading activation refers to the process by which one node in a semantic network, when active, activates related nodes.Knowledge of words exists at three different levels.Conceptual levelLemma level (syntactic aspect)lexeme level (captures a word’s phonological properties )Access to wordsMajor Types of Slips of the Tongueshifts, one speech segment disappears from its appropriate location and appears somewhere else.Exchanges :two linguistic units exchange places.Anticipations occur when a later segment takes the place of an earlier one.Perseverations occur when an earlier segment replaces a later item.Major Types of Slips of the TongueAdditions add linguistic material.deletions leave something out.Substitutions occur when one segment is replace by an intruder.Blends apparently occu r when more then one word is being considered and the two intended items “fuse” of “blend” into a single item.Common Properties of Speech ErrorsElements that interact with one another tend to come from similar linguistic environments.Elements that interact with one another tend to be similar to one another.Even when slips produce novel linguistic items, they are generally consistent with the phonological rules of the language.There consistent stress patterns in speech errors.Generation of SentencesSpeech production consists of four major stagesConceptualizing a thoughtFormulating a linguistic planArticulating the planMonitoring one’s speech/ self monitoring.Independence of planning unitsThe sequence of planning unitsChunckingGrouping individual pieces of information into larger units.。

Chapter 2 Linguistics语言学2.1 The scope of linguistics:语言学的研究范畴Linguistics is referred to as a scientific study of language.语言学是对语言的科学研究。

It may be a study of the structure of language,the history of language,the functions of language,etc.它可能研究语言的及结构,语言的历史、语言的功能等。

It is a scientific study beacause “it is based on the systematic investigation of linguistic data,conducted with reference to some general theory of language structure”(Dai Wei dong,1988:1)这是一个科学研究因为“这是基于语言数据的系统考察,和语言结构一般理论的研究之上的”2.1.1 Lyons’ distinctions 莱昂斯的区分1) General linguistics and descriptive linguistics. 普通语言学与描写语言学:The former deals with language in general whereas the latter is concerned with one particular language.前者处理一般语言,而后者涉及一个特定的语言。

2) Synchronic linguistics and diachronic linguistics. 共时语言学与历时语言学:Diachronic linguistics traces the historical development of the language and records the changes that have taken place in it between successive points in time. And synchronic linguistics presents an account of language as it is at some particular point in time.历时语言学追溯了语言的历时发展和记录了发生的连续时间点间的变化,共时语言学提供了一个账户的语言,因为它是某个特定的时间点。

LinguisticsWhat is LinguisticsLinguistics is the scientific study of language. It endeavours to answer the question--what is language and how is represented in the mind? Linguists focus on describing and explaining language and are not concerned with the prescriptive rules of the language (ie., do not split infinitives). Linguists are not required to know many languages and linguists are not interpreters.The underlying goal of the linguist is to try to discover the universals concerning language. That is, what are the common elements of all languages. The linguist then tries to place these elements in a theoretical framework that will describe all languages and also predict what can not occur in a language.Linguistics is a social science that shares common ground with other social sciences such as psychology, anthropology, sociology and archaeology. It also may influence other disciplines such as english, communication studies and computer science. Linguistics for the most part though can be considered a cognitive science. Along with psychology, philosophy and computer science (AI), linguistics is ultimately concerned with how the human brain functions.Below are several different disciplines within linguistics. The fields of phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics and language acquisition are considered the core fields of study and a firm knowledge of each is necessary in order to tackle more advanced subjects.PhoneticsPhonetics is the study of the production and perception of speech sounds. It is concerned with the sounds of languge, how these sounds are articulated and how the hearer percieves them. Phonetics is related to the science of acoustics in that it uses much the same techniques in the analysis of sound that acoustics does. There are three sub-disciplines of phonetics:∙Articulatory Phonetics: the production of speech sounds.∙Acousitc Phonetics: the study of the physical production and transmission of speech sounds.∙Auditory Phonetics: the study of the perception of speech sounds.PhonologyPhonology is the study of the sound patterns of language. It is concerned with how sounds are organized in a language. Phonolgy examines what occurs to speech sounds when they are combined to form a word and how these speech sounds interact with each other. It endeavors to explain what these phonological processes are in terms of formal rules.MorphologyMorphology is the study of word formation and structure. It studies how words are put together from their smaller parts and the rules governing this process. The elements that are combining to form words are called morphemes. A morpheme is the smallest unit of meaning you can have in a language. The word cats, for example, contains the morphemes cat and the plural -s.SyntaxSyntax is the study of sentence structure. It attempts to describe what is grammatical in a particular language in term of rules. These rules detail an underlying structure and a transformational process. The underlying structure of English for example would have asubject-verb-object sentence order (John hit the ball). The transformational process would allow an alteration of the word order which could give you something like The ball was hit by John.SemanticsSemantics is the study of meaning. It is concerned with describing how we represent the meaning of a word in our mind and how we use this representation in constructing sentences. Semantics is based largely on the study of logic in philosophy.Language AcquisitionLanguage acquistion examines how children learn to speak and how adults learn a second language. Language acquistion is very important because it gives us insight in the underlying processes of language. There are two components which contribute to language acqusition. The innate knowledge of the learner (called Universal Grammer or UG) and the environment. The notion of UG has broad implications. It suggests that all languages operate within the same framework and the understanding of this framework would contribute greatly to the understanding of what language is.Other Disciplines∙Sociolinguistics: Sociolinguistics is the study of interrelationships of language and social structure, linguistic variation, and attitudes toward language.∙Neurolinguistics: Neurolinguistics is the study of the brain and how it functions in the production, preception and acquistion of language.∙Historical Linguistics: Historical linguistics is the study of language change and the relationships of languages to each other.∙Anthropological Linguistics: Anthropological linguistics is the study of language and culture and how they interact.∙Pragmatics: Pragmatics studies meaning in context.。

Tony McEnery and Andrew Wilson. Corpus Linguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-7486-0808-7 (hardback); ISBN 0-7486-0482-0 (paperback). Reviewed by Charles F. Meyer, University of Massachusetts at Boston.The publication of Corpus Linguistics is noteworthy: as the first volume in the new series ‘Edinburgh Textbooks in Empirical Linguistics’, this textbook reflects not only the increasing importance that empirically-based studies of language are coming to play in linguistics but the prominent role that corpus linguistics has assumed among the many different empirically-based approaches to language study. In Corpus Linguistics, McEnery and Wilson (hereafter MW) very clearly introduce the field of corpus linguistics to students, providing a very effective overview of the key linguistic and computational issues that corpus linguists have to address as they create corpora and conduct analyses of them. Corpus Linguistics is divided into seven chapters that focus on a number of topical issues in corpus linguistics, issues ranging from the theoretical underpinnings of corpus linguistics to the various annotation schemes that have been developed to tag and parse corpora, the quantitative research methods used to analyze corpora, the types of linguistic studies that have been carried out on corpora, and the contributions that com-putational linguistics has made to the creation and analysis of corpora. Each of these topics is approached in a clear and readable format that will make this text valuable not just to students but to specialists in other areas of linguistics interested in obtaining information about corpus linguistics.After noting in the opening chapter (‘Early Corpus Linguistics and the Chomskyan Revolution’) that corpus linguistics is more a methodology (a way of approaching language study) than a sub-discipline in linguistics, MW continue with a discussion of the methodological assumptions that characterize corpus linguistics and distinguish it from Chomskyan app-roaches to language study. They note the difference between rationalist and empiricist approaches to language study, and detail the classic Chomskyan arguments that have been leveled over the years against empiricist studies of language. Because corpora contain data reflecting ‘performance’, they are of little value in studying ‘competence’, the most important area for linguists to study. In addition, ‘corpora are “skewed”’ (p 8), in the sense that they do not contain all of the possible structures that exist in a language. These objections led Chomsky to1value introspection as the best way of describing a language, and to reject descriptions of actual language use based on analyses of corpora. Although MW acknowledge some validity to Chomsky’s objections to corpus analyses, they counter these objections with a number of arguments in favor of corpus linguistics. A corpus, for instance, can be used to verify introspective judgments, and to overcome the problem of basing grammatical arguments on ‘artificial data’ (p 12). Moreover, c orpora can provide important information on the frequency of grammatical construc-tions, and the sophisticated software developed to analyze corpora can give the linguist access to much important information on grammatical structure present in corpora that have been tagged and parsed. Although Chapter 2 (‘What is a corpus and what is in it?’) purports to describe what a corpus is, it is primarily a chapter about what corpora look like—specifically the annotation schemes that have been developed to tag and parse them. MW only briefly discuss the issues one must confront when creating a corpus (eg the size of the corpus), and while they discuss many methodological concerns throughout the book, it would have been desirable to have grouped these issues together in a single chapter and to have discussed how the representativeness of a corpus is influenced by such variables as its length, the genres it contains, and the types of individuals whose speech and writing are included in the corpus.The strength of Chapter 2 is its discussion of annotation schemes, which is detailed and very well illustrated. MW provide a very clear overview of the TEI (Text Encoding Initiative), illustrating how the various tags developed by TEI can be used to create ‘headers’ (in which information about authors/speakers, titles, dates of publication, etc can be recorded) and to mark up texts themselves with information on paragraph boundaries, type faces, and so forth. The remainder of the chapter focuses on the various schemes that have been developed to annotate linguistic information in corpora. MW first compare tagging schemes from corpora as diverse as the British National Corpus and the CRATER Corpus of Spanish, and then describe the process of developing the CLAWS tagging schemes at Lancaster University. The chapter con-cludes with a discussion of parsing schemes and of how corpora can be annotated with markup revealing their semantic, discoursal, and prosodic structure.Chapter 3 (‘Quantitative data’) discusses the importance of using quantitative research methods to analyze corpora. MW first distinguish qualitative from quantitative research methods, and make the very im-2portant point that the linguistic claims one makes about a corpus depend crucially upon whether the corpus being analyzed is valid and repre-sentative; that is, has been created in a manner that allows the analyst to make general claims about, for instance, the genres represented in the corpus. MW then describe the major kinds of statistical analyses that can be performed on corpora. The difficulty of a chapter of this type is that statistics is such a vast area that it is hard to determine precisely how much detail needs to be provided. But the level of detail in this chapter is most appropriate, and there is much useful information provided on how corpora can be statistically analyzed — from methods as basic as frequency counts to those as sophisticated as factor analysis and loglinear analysis (as done with programs such as VARBRUL). Chapter 4 (‘The use of corpora in language studies’) surveys the kinds of empirical linguistic analyses that corpora can be used to conduct. MW open the chapter with a discussion stressing the importance of empirical studies of language, noting that they ‘enable the linguist to make statements which are objective and based on language as it really is rather than statements which are subjective and based upon the individual’s own internalised cognitive perception of the language’ (p 87). This statement is very convincingly supported in the remainder of the chapter, which contains a very good discussion of how corpora can be used to study language at all levels of linguistic structure (eg phonetics/phonology, syntax, and semantics) and from many different theoretical perspectives (eg pragmatics, sociolinguistics, and discourse study). As each of these areas are described, MW include descriptions of previous studies conducted in the areas to effectively illustrate how work in the area is conducted and has yielded important information. The first four chapters of Corpus Linguistics are concerned with issues relevant to linguists using corpora to carry out purely linguistic studies. Chapter 5 (‘Corpora and computational linguistics’) moves to an allied discipline, natural language processing (NLP), and discusses issues such as tagging and parsing from a more computational perspective. Although linguists who use corpora for grammatical analysis may not have an immediate interest in NLP, the research in this area has led directly to improvements in recent years of taggers and parsers — software respon-sible for annotating corpora and making it easier for linguists to extract information from them. The discussion in this chapter is brief, but does an excellent job of summarizing the theoretical issues underlying the development of taggers and parsers and the role that they play in areas such as lexicography and machine translation.3Chapter 6 (‘A case study: sublanguages’) draws upon much of the information presented in the previous chapters to carry out a sample grammatical analysis of three corpora from three distinct genres: a series of IBM manuals from the IBM Corpus, transcriptions of Canadian parliamentary speeches found in the Hansard Corpus, and fiction from the APHB (American Printing House for the Blind) Corpus. MW analyze these three corpora to advance the hypothesis that the language of the IBM Corpus is a ‘sublanguage’; that is, ‘a version of a natural language which does not display all of the creativity of that natural language[and which] will show a high degree of closure [emphasis in original] at various levels of description (p 148). Before pursuing this hypothesis, MW discuss the importance of evaluating a prospective corpus to determine whether the genres it contains are appropriate for the analysis being conducted, and whether the manner in which the corpus has been annotated will allow for the retrieval of the grammatical information desired. MW conclude that the corpora they have chosen are appropriate for their study of sublanguages, and they then conduct analyses to determine the degree of lexical closure, part-of-speech closure, and parsing closure that exists in each of the corpora. In general, this analysis verified MW’s hypothesis and demonstrated that the IBM Corpus (in comparison with the other corpora) is a more ‘restricted genre’ and contains fewer different types of words and sentence-types (though the words it contained corresponded to more parts of speech than the words in the other corpora did).The final chapter (‘Where to now?’) nicely rounds out the book with a discussion of issues that corpus linguists will need to address in the future corpora that they develop, a series of ‘pressures’ to increase the length of corpora, to make them conform to industry as well as academic standards, and to have corpora draw upon evolving computer technologies in their creation, such as the many multi-media currently being developed. This chapter provides a fitting conclusion to a text that provides a very perceptive overview of the field of corpus linguistics that will be a good choice for use in any introductory course on corpus linguistics. 4。

Contrastive Linguistics and CorporaStig JohansonAbstractThe paper considers different ways in which computer corpora can be used in contrastive linguistics. Examples are drawn from studies based on the English-Norwegian Parallel Corpus, a bidirectional translation corpus consisting of original texts in each of the languages and their translations into the other language. The model combines different types of corpora within the same overall framework and each type can be used to control and supplement the other. In this way it is possible to identify translation effects, and the objections which are generally raised to the use of translation corpora in contrastive studies can be overcome. Practical applications of corpus-based studies are considered, and suggestions are made for future work in the area.0.AimThe history of linguistics is marked by frequent changes in theory and method. Contrastive linguistics is no exception. This paper considers the meeting of contrastive linguistics and the new approach to the study of language which is generally referred to bythe term corpus linguistics.There has been a tremendous growth in the compilation and use of corpora.This has partly to do with the increasing interest among linguists in studying languages in use, rather than linguistic systems in the abstract, but it is primarily connected with the possibilities offered by corpora in machine-readable form, so-called computer corpora. One of the most significant recent trends is the development of multilingual corpora for use in cross-linguistic research, both theoretical and applied, which promises to lead to a revitalization of contrastive linguistics.1.What is contrastive linguistics?Contrastive linguistics is systematic comparison of two or more languages, with the aim of describing their similarities and differences. The objective of the comparison may vary: Language comparison is of great interest in a theoretical as well as an applied perspective. It reveals what is general and what is language specific and is therefore important for the study of the individual languages compared. (Johansson & Hofland 1994:25)Contrastive linguistics is thus not a unified field of study. The focus may be on general or on language specific features. The study may be theoretical, without any immediate application, or it may be applied, i.e. carried out for a specific purpose.The term ‘contrastive linguistics’, or ‘contrastive analysis’, is especially associated with applied contrastive studies advocated as a means of predicting and/or explaining difficulties of second language learners with a particular mother tongue in learning a particular target language. In the Preface to his well-known book,Lado (1957) expresses the rationale of the approach as follows:The plan of the book rests on the assumption that we canpredict and describe the patterns which will cause difficultyin learning and those that will not cause difficulty.It was thought that a comparison on different levels (phonology, morphology, syntax, lexis, culture) would identify points of difference/difficulty and provide results that would be important in language teaching:The most efficient materials are those that are based upon a scientific description of the language to be learned, carefully compared with a parallel description of the native language of the learner. (Fries 1945: 9)The high hopes raised by applied contrastive linguistics were dashed. There are a number of problems with the approach, in particular the problem that language learning cannot be understood by a purely linguistic study. So those who were concerned with language learning instead turned to the new disciplines of error analysis, performance analysis or interlanguage studies, and contrastive analysis were rejected by many as an applied discipline.In spite of the criticism of applied contrastive linguistics, contrastive studies were continued, and their scope was broadened.2.New directionsAlthough Lado (1957) included a comparison of cultures, early contrastive studies focused on what has been described as microlinguistic contrastive analysis (James 1980: 61ff): phonology,grammar, lexis. Examples f research questions:●What are the consonant phonemes in languages X and Y?how do they differ in inventory, realization, and distribution?●What is the tense system of languages X and Y?●What are the verbs of saying in languages X and ?With the broadening of linguistic studies in general in the 1970s and 1980s, contrastive studies became increasingly concerned with macrolinguistic contrastive analysis (James 1980: 98ff): text linguistics, discourse analysis. Examples of research questions:●How is cohesion expressed in languages X and Y?●How are the speech acts of apologizing and requesting expressedin languages X and Y?●How are conversations opened and closed in languages X and ?When questions of this kind are raised, it becomes increasingly important to base the contrastive study on texts.3.The role of corporaIn the course of last couple of decades we have seen a breakthrough in the use of computer corpora in linguistic research. They are used for a wide range of studies in grammar, lexis, discourse analysis, language variation, etc. they are used in both synchronic and diachronic studies – and increasingly also in crosslinguistic research.Salkie (199) goes as far as to say:Parallel corpora [i.e. multilingual corpora] are a valuablesource of data; indeed, they have been a principal reason forthe revival of contrastive linguistics that has taken place inthe 1990s.In the rest of this paper I will focus on the role of corpora in contrastive linguistics. As a starting-point, I will use the possibilities offered by bilingual corpora as listed by Aijmer and Altenberg (1996: 12):⏹they give new insights into the languages compared –insightsthat re likely to be unnoticed in studies of monolingual corpora;⏹they can be used for a range of comparative purposes andincrease our understanding of language-specific, typological and cultural differences, as well as of universal features;⏹they illuminate differences between source texts and translations,and between native and non-native texts;they can be used for a number of practical applications, e.g. in lexicography, language teaching, and translation.I will take up each of these points in turn, in the order in which they are listed above. For ease of reference, I will refer to bilingual and multilingual corpora as multilingual corpora and to the paper by Aijmer and Altenberg (1996) simply as Aijmer & Altenberg.4.Analytical comparisonComparison is a good way of highlighting the characteristics of the things compared. This applies to language comparison as well as more generally, and it is notable that this is the first point in Aijmer & Altenberg’s list. Vilém Mathesius, founder of the Linguistic Circle of Prague, spoke about analytical comparison, or linguistic characterology, as a way of determining the characteristics of each language and gaining a deeper insight into their specific features (Mathesius 1975). He used it in his comparison of the word order of English and Czech, and the study has been followed up by Jan Firbas in particular. In the opening chapter of his Functional Sentence Perspective in Written and Spoken Communication (1992:3ff), Firbas compares an original text in French with its translation into English, German, and Czech, and he uses the same sort of comparison later in the book. Firbas says:The contrastive method proves to be a useful heuristic toolcapable of throwing light on the characteristic features of thelanguages contrasted; … (Firbas 1992: 13).There is no difference in principle between the contrastive method of Firbas and the way we use multilingual corpora, except that the study can be extended by the use of computational techniques. As an example, consider Jarle Ebeling’s study of Norwegian Parallel Corpus (Ebeling 2000). Ebeling studies three constructions which are found in both languages, termed full presentatives (1), bare presentatives (2), and have/ha-presentatives (3):(1)There’s a long trip ahead of us.Det ligger en lang reise foranoss.(2)A long trip is ahead of us.En lang reise ligger foran oss.(3)We have a long trip ahead of us.Vi har en lang reise foran oss.Although the constructions are similar in syntax, semantics, and discourse function, there are important differences. The contrastive study defines these differences and at the same time makes the description of the individual languages more precise.5.Contrastive studiesHighlighting the characteristics of the individual languages and defining the relationship between languages are just differences in perspective. In a comparative study the focus may be on language0specific, typological or universal features, as Aijmer & Altenberg say in their second point. Here I am particularly concerned with contrastive studies focusing on a comparison of paris of languages.One of the moist serious problems of contrastive studies is the problem of equivalence. How do we know about what to compare? What is expressed in one language by, for example, modal auxiliaries could be expressed in other languages in quite different ways. In this case a comparison of modal auxiliaries does not take us very far.Most contrastive linguists have either explicitly or implicitly made use of translation as a means of establishing cross-linguistic relationships, and in his book on contrastive analysis Carl James reaches the conclusion that translation is the best basis of comparison;We conclude that translation equivalence, of this rather rigorously defined sort {including interpersonal and textual as well as ideational meaning} is the best available TC [tertium comparationis] for CA [contrastive analysis]. (James 1980: 178)In his paper on ‘the translation paradigm’Levenston suggests that contrastive statements…may be derived from either (a) a bilingual’s use of himself as his own informant for both languages, or (b) close comparison of a specific text with its translation. (Levenston 1965: 225)the use of multilingual corpora, with a variety of texts and a range of translators represented, increases the validity and reliability of the comparison. It can indeed be regarded as the systematic exploitation of the bilingual intuition of translators as it is reflected in the pairingof source and target language expressions in corpus texts.It is probably not very well known that a corpus of this kind was set up for the Serbo-Croatian –English Contrastive Project (Filipović1969). The reasoning was formulated in this way by Spalatin:(1)similarity between languages is not necessarily limited tosimilarity between elements belonging to correspondinglevels in the languages concerned, and (2) similarity betweenlanguages is not necessarily limited to similarity betweenelements belonging to corresponding classes or ranks in thelanguages concerned. (Spalatin 1969: 26)The basis of comparison was to be a bidirectional corpus, with English texts and their translations into Serbo-Croation (half of the Brown Corpus was selected!) and corresponding material consisting of texts in Serbo-Croatian and their translations into English. The translations were especially commissioned for the project and were done by ‘reasonably competent professional translators’who were ‘deliberately chose outside the Project’(Filipović1971: 84). Apart from the fact that we have used published translations, this is exactly the model which we chose many years later fro theEnglish-Norwegian Parallel Corpus. We were unaware of the parallel when we started the project, and the matter came up only recently in connection with Jarle Ebeling’s thesis work.An example of a corpus-based contrastive study is Berit Løken’s (1996, 1997) investigation of expressions of possibility in English and Norwegian, based on the English-Norwegian Parallel Corpus. One of her findings was that there ware major differences in the expression of epistemic possibility, although the two languages have similar means at their disposal. English epistemic modals are rendered in Norwegian in approximately half the cases by an adverb (4, 5) or by combination of a modal and an adverb (6):(4)You may not know about this one: it’s a modern sin.Du kjenner kanskje[lit. ‘prehaps’] ikke til den, det er en moderne synd.(5)I had become frightened on the way home, thinking that myfather might be waiting up for me.På veien hjem var jeg blitt Ganske redd da jeg tenkte på at faren min kanskje [lit. ‘perhaps’] satt oppe og ventet på meg.(6)At moments … he realized that he might be carrying things toofar.Iblant …innsåhan at han kanskje kunne[lit. ‘perhaps could’] drive det concludes:The opposite relationship, i.e. where Norwegian epistemic modals were translated by some other expression than an English modal, was far less frequent. Løken concludes:Most of the differences between English and Norwegianfound in the corpus material may be results of the differingdegrees of grammaticalisation of the two sets of modals, theNorwegian modals being less grammaticalised than theEnglish ones. (Løken 1997: 55f.)Løken’s observations on English vs. Norwegian have later been shown also to apply English vs. Swedish in a study by Aijmer (199), who associates the results with the relative degree of grammaticalisation of Swedish kan and English may/might. These studies illustrate how hypotheses on more general cross-linguistic differences can be inspired by corpus findings. In this connection, I would like to quote from Andrew Chesterman’s recent book onContrastive Functional Analysis:Corpus studies are a good source of hypotheses. But they areabove all a place where hypotheses are tested, albeit not theonly place. The more stringently a given hypothesis is tested– against a corpus, other speakers’ intuitions, in a controlledexperiment …–the better corroborated it will be.(Chesterman 1998: 60f.)The use of a corpus is not bound to any one linguistic theory.The investigator is free to choose whatever linguistic theoryis appropriate to account for the data.6.Translation studiesIn their third point Aijmer & Altenberg mention the study of differences between source texts and translations, i.e. original and translated texts in the same language. The study if the nature of translated texts by means of corpora was advocated by Baker (1993), and a special issue of a periodical for translators was indeed recently devoted to the ‘corpus-based approach’ (META, December 1998). In her opening paper the editor writes:…a growing number of scholars in translation studies have begun to seriously consider the corpus-based approachas a viable and fruitful perspective within which translationand translating can be studied in a novel and systematic way.(Laviosa 1998: 474)A study of translated texts may focus on features induced by the source language (as in Gellerstam 1996) or on more general characteristics of translated texts (as suggested by Baker 1993).In my study of the English verbs love and hate and their Norwegian correspondences (Johansson 1998c), I discovered major differences in distribution between original vs. translated texts; see Figure 1. The figure shows that the English verbs are about three times as much as common as their Norwegian counterparts in the original fiction texts of the English-Norwegian Parallel Corpus. In the translated texts, however, the frequencies for the Norwegian verbs go up while the figures for the English verbs go down, presumably induced by the source language. Examples of this kind can easily be multiplied.Figure 1. The Distribution of English love and hate, and Norwegian elske and hate in original and translated fiction texts of the English-Norwegian Parallel Corpus (30 texts of each type)An example of study of more general features of translation is the investigation by Linn øverås (1996, 1998) of explicitation in translated English and Norwegian, based on the English-Norwegian Parallel Corpus. He following examples illustrate a rise in explicitness in translation from English into Norwegian (7, 8), and vice versa (9, 01):(7)At least I haven’t had to pin anything this time, he said.Denne gangen slap jeg i alle fall å bruke skruer, sa ortopeden. [lit.‘said the orthopedist’](8)Her companion hesitated, looked at her, then leaned back andreleased the rear door.Den andre kvinnen nølte og så på piken, så snudde hun seg og trakk opp låseknappen på døren bak. [lit. ‘looked at the girl’](9)En av dem får tak i øksa til tømmermannen. [lit. ‘one of them’]But then one of them got hold of an axe belonging to the carpenter.(10)Husk nå at du ikke gir fra deg så mye som en bitteliten lyd.[lit. ‘now remember’]Now remember, she admonished, not a sound.In (7) and (8) the translator has inserted a more specific referential expression, in (9) connectors are added, and in (10) there is a reporting clause without a corresponding form in the original text. Such changes were far more common, in both directions of translation, than the opposite type of shift (implicatrion). The ultimate objective of the studies of øverås is to reach conclusions ontranslation norms. To study translation norms, we have collected a small corpus of translations where some of the best and most experienced translators in Norway have been commissioned to translate the same texts, a short story and a scientific article.Now, if it’s the case that translated texts have particular features, how can we then use such material for contrastive studies? This question will be addressed in the next section.7.Which type of corpus for which type of study?This question has been discussed in a number of papers, e.g. Lauridsen (1996), Granger (1996), Teubert (1996), and Johansson (1998a, 1998b), and therefore I will be as brief as possible. The nature of the corpus will vary depending upon the type of study. What is common for all the types of study we are concerned with here is that they require parallel corpora of some sort or other, in particular:⏹multilingual corpora of original texts and their translations (forcontrastive studies and translation studies)⏹multilingual corpora of original texts which are matched bycriteria such as genre, time of composition, etc. (for contrastive studies)monolingual corpora consisting of original and translated texts (for translation studies)Rather than discussing the possibilities and limitations of each type, I will just mention that all three types can be combined within the same overall framework, as we have done in the English-Norwegian Parallel Corpus (Johansson 1998b; see Figure 2), and each type can then be used to control and supplement the other. In this way, we can use the same corpus both for contrastive studies and translation studies and then circumvent the problem raised in Section 6 above.Figure 2. The Structure of the English-Norwegian Parallel CorpusA special type of corpus is required for the study of learner language, including differences between native and non-native texts (cf. Aimer & Altenberg ’s third point) and between texts produced by learners with different mother-tongue backgrounds. A great deal of progress has been made recently in this area in connection with theInternational Corpus of Learner English (Granger 1998). The studies we get here are not contrastive in the narrow sense, but can be viewed as representing a corpus-based approach to error analysis and performance analysis.8.ApplicationsIn their last point Aijmer & Altenberg draw attention to a number of practical applications: in lexicography, language teaching, and translation. Those who know something of the history of linguistics are well aware of the danger of making exaggerated claims. In the decades after the Second World War there was a boom for applied contrastive linguistics. The hopes were dashed, however (see Section 1 above).Now that there seems to be a new boom fro contrastive linguistics, brought about by the new corpus methodology, it is important not to overstate the claims of this approach. No matter how good a multilingual corpus is, it will not allow us to make safe predictions of learners’difficulties. Nevertheless, corpus-based contrastive studies have important uses, in particular:⏹the production of new bilingual dictionaries;⏹the development of new teaching materials, including contrastivegrammar;⏹the development of materials for the training of translators, e.g.conscious-raising exercises dealt with problem X or Y?To end this brief section on applications, I will quote from a previous paper of mine:One of the most exciting perspectives of corpora is that they may be used to good advantage both in research and teaching …. It has been a perennial problem in language teaching to find ways of going from theory to practice, from grammar and dictionary to language use. If learners are provided with a corpus as well as a grammar and a dictionary …, they can more easily see the connection between language description and language use. They can more easily pick an appropriate form from a more efficient guide to language in use. With access to a corpus, language learning may even become a process of discovery, a form of research – an exciting, and probably also effective, way of learning. 9johansson 1998a: 286f.)9.ConclusionIn this survey I have taken contrastive linguistics in a very broad sense. Not everybody will agree with this broad definition, but I hope to have shown that corpora have an important role to play in all the areas I have taken up. The use of corpus-based methods is in many cases a follow-up and an extension of types of studies which were carried out by traditional methods in the past, e.g. the use of translation by Firbas and Levenston. But with the help of a corpus we get unprecedented opportunities to study and contrast language in use, including frequency distributions and stylistic preferences. Corpora are absolutely essential for macrolinguistic studies, but they will also enrich studies of lexical and grammatical patterns.The development is only just beginning, however. I should like to draw attention to some particularly interesting challenges for the future:⏹We need more work on multilingual corpora – multilingual in atrue sense, with a range of languages represented. The study of such corpora will increase our knowledge of language-specific, typological, and universal features.⏹We need to carry on the work on corpora of translated texts andlearner language, with systematic variation of the source and target language of the translations and of the mother tongue of the learners. In this way we can uncover general as well as language-specific features of translated texts and learner language.We need a new generation of grammars and dictionaries, based on the study of language in use. Ideally –whether are talking about one or more languages –we need a new integrated language description, in electronic form, with links between grammar, dictionary, and corpus (Johansson 1998b). There are some beginnings, but we are still far from this goal.To end this brief survey, it would seem appropriate to refer to a prediction made at the beginning of work on the English-Norwegian Corpus:The importance of computer corpora in research on individual languages is now firmly established. If properly compiled and used, bilingual and multilingual corpora will similarly enrich the comparative study of languages. (Johansson and Hofland 2994: 36)I hope the future will prove that we were right.。

语言学常用术语A List of Commonly-used LinguisticTerminology语言学常用术语表Part I General Terms通用术语Acquisition 习得Agglutinative language 粘着语Anthropology 人类学Applied linguistics 应用语言学Arbitrariness 任意性Artificial intelligence (AI)人工智能Behaviorism 行为主义Behaviorist psychology 行为主义心理学Bilingualism 双语现象Cognition 认知Cognitive linguistics 认知语言学Cognitive science 认知科学Comparative linguistics 比较语言学Computational linguistics 计算语言学Corpus-linguistics 语料库语言学Creole 克里奥耳语;混合语Culture 文化Descriptive linguistics 描写语言学Design features 识别特征Developmental psycholinguistics 发展心理语言学Diachronic/historical linguistics历时语言学Dialect 方言Dialectology 方言学Displacement 不受时空限制的特性Dualism 二元论Duality 二重性Epistemology认识论Etymology 辞源学Experimental psycholinguistics 实验心理语言学Formalization 形式化Formal linguistics 形式语言学Forensic linguistics 法律语言学Functionalism 功能主义General linguistics 普通语言学Grammaticality 符合语法性Ideography 表意法Inflectional language 屈折语Inter-disciplinary 交叉性学科的Isolating language 孤立语Langue 语言Macro-sociolinguistics 宏观社会语言学Mentalism 心智主义Micro-sociolinguistics 微观社会语言学Montague grammar蒙太古语法Neuro-linguistics 神经语言学Orthography 正字法Orthoepic 正音法的Paradigmatic 聚合关系Parole 言语Pedagogy 教育学;教授法Philology 语文学Philosophy 哲学Phonography 表音法Pidgin 皮钦语;洋泾浜语Polysynthetic language 多式综合语Prescriptive linguistics 规定语言学Psycholinguistics心理语言学Psychology 心理学Semeiology 符号学Sociology 社会学Speech 言语Sociolinguistics社会语言学Structuralism 结构主义Synchronic linguistics 共时语言学Syntagmatic 组合关系Theoretic linguistics 理论语言学Universal grammar 普遍语法Universality 普遍性Part II Phonology音位学Ablaut 元音变化Acoustic phonetics 声学语音学Affricate 塞擦音Allophone 音位变体Alveolar 齿龈音Articulatory phonetics 发音语音学Auditory phonetics 听觉语音学Articulatory variables 发音变体Aspiration 送气Assimilation 同化Back of tongue舌根Back vowel后元音Bilabial 双唇音Blade of tongue 舌面Broad transcription 宽式音标Central vowel 中元音Collocation 搭配Complementary distribution互补分布Consonant 辅音Dental 齿音Diacritics 变音符号;附加符号Diphthong 双元音Distinctive features 区别性特征Fricative 擦音Front vowel 前元音Glide 音渡Glottal 喉音Hard palate 硬腭International Phonetic Alphabet 国际音标Intonation 语调Liquid 流音Manner of articulation 发音方法Minimal pair最小对立体Narrow transcription 严式音标Nasal 鼻音Nasal cavity 鼻腔Palatal 腭音Pharyngeal cavity 咽腔Phone音素Phoneme音位Place of articulation 发音部位Plosive爆破音Phonemic contrast 音位对立Phonetics语音学Rounded圆唇音Soft palate (velum)软腭Spectrograph 频谱仪Speech organ 发音器官Speech sounds 语音Stop塞音Stress 重音Suprasegmental features 超音段特征Teeth ridge (alveolus) 齿龈隆骨Tip of tongue 舌尖Tone 音/声调Unrounded 非圆唇音Uvula 小舌Velar 软腭音Vocal cords 声带Voiced 浊音Voiceless清音Voicing 浊音化Vowel 元音Part III Morphology形态学Acronym 首字母缩略词Affix 词缀Affixation 词缀法Back-formation 逆成法Blending 紧缩法Borrowing 借用Bound morpheme 粘着语素Clipped words 缩略词Coinage 创新词Compounding 合成法Conversion 转换法Closed class 封闭类Derivational morpheme 派生语素Free morpheme 自由语素Idiom 成语Inflection 屈折变化Inflectional morpheme 屈折语素Jargon 行话Lexicography 辞典编纂学Loan words 外来词Morpheme 语素Open class 开放类Prefix 前缀Productive 能产的Root 词根Stem 词干Suffix 后缀Suppletion 异根Word formation 构词法Part IV Syntax句法学Abstract noun 抽象名词Accusative 宾格Active voice 主动态Adjective 形容词Adjunct 附加状语Adverbial 状语Agreement 一致关系Anaphor 照应语Antecedent 先行词Apostrophe 省略符号Apposition 同位语Article 冠词Attribute 定语Case 格Cleft sentence 分裂句Collective noun 集合名词Comment 述题Competence 语言能力Complement 补语Compound predicate 复合谓语Compound sentence 复合句Concession relation 让步关系Concrete noun 具体名词Connective 连接词Constituent 句子成分Content word 实词Continuous aspect 进行体Coordinate clause 并列句Coordinating conjunction 并列连词Copula 系动词Declarative sentence 陈述句Descriptive adequacy 描写充分性Direct object 直接宾语Discontinuous constituents 非连续性成分D-structure 深层结构Dual number 双数Dummy word 伪词Endocentric construction 向心结构Ergative 作格Exclamatory sentence 感叹句Existential sentence 存在句Exocentric construction 离心结构Explanatory adequacy 解释充分性Feminine 阴性Finite clause 限定性分句Finite verb 限定性动词Function word 功能词Generic term 泛指性成分Genitive case 所有格;属格Gender 性Gerundive 动名词Habitual aspect 习惯体Head 中心词Immediate Constituent Analysis (IC Analysis) 直接成分分析法Imperative mood 祈使语气Imperative sentence 祈使句Imperfective aspect 非完成体Indirect object 间接宾语Infinitive 不定式Inflectional affix 屈折前缀Informal language 非正式语言Intensifier 强势语Interjection 感叹词Interrogative sentence 疑问句Intransitive verb 不及物动词Intransitivity 不及物性Irregular verb 不规则动词Labeled tree diagram 加标记的树形图Language faculty 语言器官Lexical verb 实词性动词Main clause 主句Masculine 阳性的Matrix sentence 主句Middle voice 中动语态Modality 情态Modal verbs 情态动词Modification 修饰Modifier 修饰语Morphological process 形态过程Move 移位Negation 否定Neuter gender 中性Nominal 名词性的Nominal clause 名词性分句Nominalization 名物化Nominative case 主格Non-place predicate 空位述谓结构Numeral 数词Object 宾语Objective 宾格Oblique case 斜格Observational adequacy 观察充分性One-place predicate 一位述谓结构Onomatopoeia 拟声词Particle 小品词Parts of speech 词性Passive voice 被动语态Past perfect tense 过去完成时Past tense过去时Perfective aspect 完成体Performance 语言运用;言语行为Personal pronoun 人称代词Personification 拟人化Phrasal verb 短语动词Phrase 短语Phrase structure rules (PS-rules) 短语结构规则Plural 复数的Plurality 复数性Postposition 后置词Postpositional phrase 后置性短语Predicate 谓词Preposition 介词Prepositional phrase 介词性短语Present tense 现在时Progressive aspect 进行体Projection principle 投射原则Pronominal 代词性的Pronoun 代词Quantifier 数量词Reciprocal pronoun 互指代词Reflexive pronoun 反身代词Reflexive verb 反身动词Relative adverb 关系副词Relative clause 关系状语Relative pronoun 关系代词Rhetorical question 反意疑问句Sentence 句子Sentential 句子的Sentential complement 句子性补语Simple sentence 简单句Singular 单数的Singularity 单数性S-structure 表层结构Subject 主语Subjective 主格Subordinate 从属句Substantive 实词Syntactic function 句法功能Tag question 附加疑问句Tense 时态Topic 主题Transformational-generative grammar (TG grammar) 转换生成语法Transitive verb 及物动词Transitivity 及物性Two-place predicate 二位述谓结构Unaccusativity 动词的非宾格性Verb 动词Verbal behavior 言语行为Voice 语态Word classes 词类Word order 词序Yes-no question 是非问句;一般疑问句Part V Semantics语义学Agent 施事Antonym 反义词Antonymy 反义关系Beneficiary 受益者Color word 色彩词Complementarity 互补性反义关系Componential analysis 成分分析法Contradiction 自相矛盾的说法Deictic center 指示中心Deixis 指示语Downgrade 语义降格Experiencer 经历者Homography 同形异音异义Homonymy 同音异义Hyponym 下义词Hyponymy 下义Instrument 工具Locative 地点Meaningfulness 有意义Naming 命名论Participant role 参与者角色Patient 受事Person deixis 人称指示语Place deixis 地点指示语Polysemy 一词多义Possible world 可能世界Predication analysis 述谓结构分析Recipient 接收者Reference 所指Referent 所指对象Selectional restrictions 选择限制Semantic role 语义角色Sense 意义Superordinate 上义词Synonym 同义词Synonymy 同义关系Theme 受事Theta ro le (θ-role) 语义角色Time deixis 时间指示语Truth condition 真值条件Valency 配价Part VI Pragmatics语用学Addressee 说话对象Adjacency pair 邻接对Context 语境;上下文Conversational implicature 会话含义Cooperative principle 合作原则Direct speech 直接话语Discourse 话语Distal 远指Encyclopedic knowledge 百科知识Euphemism 委婉语Focus 焦点Generalized implicature 广义含义Given vs. new information 已知与未知信息Honorific 敬语Illocutionary act 言外行为Illocutionary force 言外之力Implicature 含义Indirect speech 间接话语Informativeness principle 信息原则Manner implicature 方式含义Maxim of manner 方式准则Maxim of quality 质量准则Maxim of quantity 数量准则Maxim of relation 关联准则Performative 施为句Performative verb 施为动词Perlocutionary act 言后行为Potential implicature 可能含义Potential presupposition 可能预设Pre-announcement 事先声明Preparatory condition 准备条件Presupposition预设Presupposition suspension 预设中止Presupposition trigger 预设激发Propositional act 命题行为Propositional content 命题内容Propositional relation 命题关系Proposition 命题Proximal 近指Quality implicature 质的含义Quantity implicature 量的含义Scalar implicature 标尺含义Schema 图式Self-repair 自我修正Sincerity condition 诚实原则Speaker 说话者Speech act 言语行为Text 语篇Turn 话轮Turn-taking 话轮转换。

语料库语言学之我见语料库语言学,是二十世纪中后期兴起的一门语言类研究科学。

它包含两方面的含义:一是指以现实中人们运用语言的实例为基础进行的语言研究。

一是指以语料为语言描写的起点,或以语料为验证有关语言假说的方法。

所以概括这两者,我们可以说语料库语言学是一种以语料库为基础的语言研究方法。

其宗旨是通过大规模真实语料的调查来发现和总结自然语言的各种语言事实和语言规律。

一、语料库语言学的重要性语料库的使用促进了语言研究的发展,同时语料库和语料库语言学在当今语言研究由高度抽象转向语言的实际使用这个过渡中起着十分重要的作用:一是提供真实语料;二是提供统计数据;三是验证现行的理论;四是构建新的理论。

这些可以说是语料库和语料库语言学的实用价值。

传统的语言研究大多是在个人的经验积累到一定程度的基础上,产生对于语言规律的感悟。

需要长时间的知识积累和材料搜集,费时耗力。

但因为个人时间精力和思维方式的限制,仍然常常不免有挂一漏万的缺憾。

语料库的发展为人们进行语言研究提供了得力的手段和工具,它的存储容量和处理语言材料的能力是任何个人头脑所无法比拟的。

利用语料库所提供的语料,语言研究者可以进行分析,从而概括语言运用规律;可以运用语料库验证已有各语言规则的合理性和客观性,从而使得语言研究得出的结论越来越接近语言事实本身。

二、语料库语言学的发展历程运用语料库进行语言研究可以追溯到十九世纪末,但当时的研究手段还只停留在卡片制作和人工检索的阶段,其成果也仅用做编辑语法书或词典的参考。

那时在电脑语料库问世之前,对真实语料的收集和研究不仅在数量,规模和代表性方面很受局限,而且检索起来也很费力费时。

二十世纪八十年代至九十年代是语料库语言学发展的第二阶段,其标志之一是世界各地都开始建设自己的语料库并且开始跨国联合建立国际性的语料库。

在国外有代表性的是九十年代集有1亿词次的英国国家语料库。

它汇集了全球20多个国家和地区的英语语料,单是每个子语料库就已经收有书面和口头语料各50万次等等。

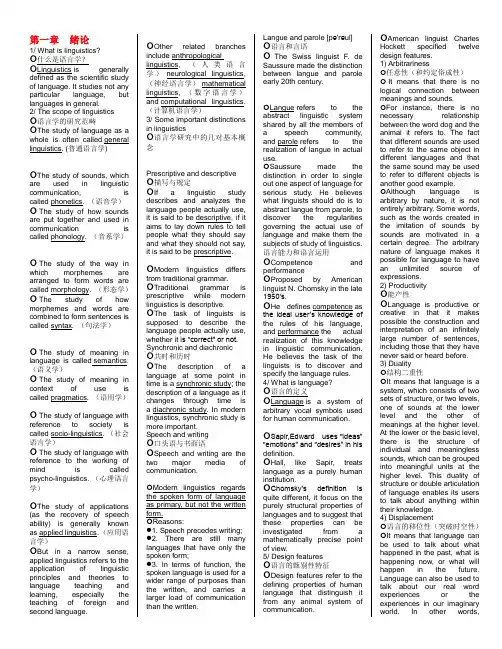

第一章绪论1/ What is linguistics?什么是语言学?Linguistics is generally defined as the scientific study of language. It studies not any particular language, but languages in general.2/ The scope of linguistics语言学的研究范畴The study of language as a whole is often called general linguistics. (普通语言学)The study of sounds, which are used in linguistic communication, is called phonetics. (语音学) The study of how sounds are put together and used in communication is called phonology. (音系学) The study of the way in which morphemes are arranged to form words are called morphology. (形态学) The study of how morphemes and words are combined to form sentences is called syntax. (句法学)The study of meaning in language is called semantics. (语义学)The study of meaning in context of use is called pragmatics. (语用学) The study of language with reference to society is called socio-linguistics. (社会语言学)The study of language with reference to the working of mind is called psycho-linguistics. (心理语言学)The study of applications (as the recovery of speech ability) is generally known as applied linguistics. (应用语言学)But in a narrow sense, applied linguistics refers to the application of linguistic principles and theories to language teaching and learning, especially the teaching of foreign and second language. Other related branchesinclude anthropologicallinguistics, (人类语言学) neurological linguistics,(神经语言学) mathematicallinguistics, (数字语言学)and computational linguistics.(计算机语言学)3/ Some important distinctionsin linguistics语言学研究中的几对基本概念Prescriptive and descriptive描写与规定If a linguistic studydescribes and analyzes thelanguage people actually use,it is said to be descriptive, if itaims to lay down rules to tellpeople what they should sayand what they should not say,it is said to be prescriptive.Modern linguistics differsfrom traditional grammar.Traditional grammar isprescriptive while modernlinguistics is descriptive.The task of linguists issupposed to describe thelanguage people actually use,whether it i s “correct” or not.Synchronic and diachronic共时和历时The description of alanguage at some point intime is a synchronic study; thedescription of a language as itchanges through time isa diachronic study. In modernlinguistics, synchronic study ismore important.Speech and writing口头语与书面语Speech and writing are thetwo major media ofcommunication.Modern linguistics regardsthe spoken form of languageas primary, but not the writtenform.Reasons:●1. Speech precedes writing;●2. There are still manylanguages that have only thespoken form;●3. In terms of function, thespoken language is used for awider range of purposes thanthe written, and carries alarger load of communicationthan the written.Langue and parole [pə'rəul]语言和言语The Swiss linguist F. deSaussure made the distinctionbetween langue and paroleearly 20th century.Langue refers to theabstract linguistic systemshared by all the members ofa speech community,and parole refers to therealization of langue in actualuse.Saussure made thedistinction in order to singleout one aspect of language forserious study. He believeswhat linguists should do is toabstract langue from parole, todiscover the regularitiesgoverning the actual use oflanguage and make them thesubjects of study of linguistics.语言能力和语言运用Competence andperformanceProposed by Americanlinguist N. Chomsky in the late1950’s.He defines competence asthe ideal user’s knowledge ofthe rules of his language,and performance the actualrealization of this knowledgein linguistic communication.He believes the task of thelinguists is to discover andspecify the language rules.4/ What is language?语言的定义Language is a system ofarbitrary vocal symbols usedfor human communication.Sapir,Edward uses “ideas”“emotions” and “desires” in hisdefinition.Hall, like Sapir, treatslanguage as a purely humaninstitution.Chomsky’s definition isquite different, it focus on thepurely structural properties oflanguages and to suggest thatthese properties can beinvestigated from amathematically precise pointof view.5/ Design features语言的甄别性特征Design features refer to thedefining properties of humanlanguage that distinguish itfrom any animal system ofcommunication.American linguist CharlesHockett specified twelvedesign features.1) Arbitrariness任意性(和约定俗成性)It means that there is nological connection betweenmeanings and sounds.For instance, there is nonecessary relationshipbetween the word dog and theanimal it refers to. The factthat different sounds are usedto refer to the same object indifferent languages and thatthe same sound may be usedto refer to different objects isanother good example.Although language isarbitrary by nature, it is notentirely arbitrary. Some words,such as the words created inthe imitation of sounds bysounds are motivated in acertain degree. The arbitrarynature of language makes itpossible for language to havean unlimited source ofexpressions.2) Productivity能产性Language is productive orcreative in that it makespossible the construction andinterpretation of an infinitelylarge number of sentences,including those that they havenever said or heard before.3) Duality结构二重性It means that language is asystem, which consists of twosets of structure, or two levels,one of sounds at the lowerlevel and the other ofmeanings at the higher level.At the lower or the basic level,there is the structure ofindividual and meaninglesssounds, which can be groupedinto meaningful units at thehigher level. This duality ofstructure or double articulationof language enables its usersto talk about anything withintheir knowledge.4) Displacement语言的移位性(突破时空性)It means that language canbe used to talk about whathappened in the past, what ishappening now, or what willhappen in the future.Language can also be used totalk about our real wordexperiences or theexperiences in our imaginaryworld. In other words,language can be used to refer to contexts removed from the immediate situations of the speaker.5) Cultural transmission文化传播性While we are born with the ability to acquire language, the details of any language are not genetically transmitted, but instead have to be taught and learned anew.********************************** Chapter 2 Phonology 音系学1.The phonic medium of language语言的声音媒介Speech and writing are the two media used by natural languages as vehicles for communication.Of the two media of language, speech is more basic than writing. Speech is prior to writing. The writing system of any language is always “invented” by its users to record speech when the need arises.For linguists, the study of sounds is of greater importance than that of writing.The limited ranges of sounds which are meaningful in human communication and are of interest to linguistic studies are the phonic medium of language (语言的声音媒介) .The individual sounds within this range are the speech sounds (语音).2.What is phonetics?什么是语音学?Phonetics is defined as the study of the phonic medium of language;It is concerned with all the sounds that occur in the world’s languages.语音学研究的对象是语言的声音媒介,即人类语言中使用的全部语音。

282018年06期总第394期高等教育研究ENGLISH ON CAMPUSCorpus Linguistics and Language Teaching文/汪倩 胥倩【Abstract】Language is the carrier of our lives, is an indispensable part of our lives, there is no language we cannot be called human. Since language is so important to us, human beings, to some extent, been studying languages in different ways during the long history of mankind. Corpus Linguistics is “language research based on real-life examples of language use”. It relies on the real language data, the use of computer research, classification, labeling, analysis. And in my thesis, according to the theory of lexical grammar and corpus exact methods,in order to study and describe English objectively and accurately. Also, basing on the corpus, English learners has made significant achievements. So, English teaching workers in China should be combined with the actual application ofcorpus linguistics in teaching research.【Key words】Corpus linguistics; Lexical grammar; English teaching; Language system 【作者简介】汪倩,胥倩,西华师范大学。

Chapter 1 Linguistics and Language◆Teaching Objectives✓To know the scope of linguistics roughly✓To understand the definition, the design features and the functions of language in details✓To have some ideas about several important distinctions in linguistic study◆Time Arrangement✓Altogether 2 periods.1.1 What is Linguistics?1.1.1 Definitions of Linguistics (p.1)◆Linguistics is the science of language.◆Linguistics is the scientific study of language.◆Linguistics is a discipline that describes all aspects of language and formulatetheories as to how language works.◆In linguistics, data and theory stand in a dialectical complementation. That is, atheory without the support of data can hardly claim validity, and data without beingexplained by some theory remain a muddled mass of things.◆The process of linguistic study: observing linguistic facts (displaying somesimilarities) & making generalizations → formulatinghypotheses based on the generalizations → testing thehypotheses repeatedly by further observations to fullyprove their validity → constructing a linguistic theory 1.1.2 The Scope of Linguistics (p.2)1.1.2.1 Main branches of linguistics (phonological, morphological, syntactic, semantic &pragmatic)Phonetics –the study of human speech sounds, including the production of speech, that is how speech sounds are made, transmitted and received, thedescription and classification of speech sounds, words and connectedspeech, etc.Phonology -- he study of sound pattering, the rules governing the structure, distribution, and sequencing of speech sounds and the shape of syllableMorphology – concerned with the internal organization of words.Syntax – the study of sentence structure, the arrangement of words.Semantics – the study of meaning.Pragmatics – the study of meaning in context.1.1.2.2 Macrolinguistics 宏观语言学(p.3)Linguistics is not the only field concerned with language. Language is not an isolated phenomenon, it’s a social activity carried out in a certain social environment by human beings. Therefore, the study of language has established close links with other branches of sciences or social studies, resulting in some interdisciplinary branches of linguistic study.Sociolinguistics – the study of the characteristics of language varieties, the characteristicsof their functions, and the characteristics of their speakers.Psycholinguistics – the study about how humans learn language and the relationship oflinguistic behavior and the psychological processes in producing andunderstanding language.Applied linguistics – 1) the study of the application of linguistic theories and methods toother fields2) the application of linguistic theories, methods, and findings to thestudy of language learning and teaching.Neurolinguistics – the study of the function of the brain in language development and usein human beings, examining the brain’s control over the processes ofspeech and understanding.Anthropological linguistics – the study of variation and use in relation to the culturalpatterns and beliefs of human race; the study of therelationship between language and culture in a community,e.g. its traditions, beliefs, and family structure.Computational linguistics – the study of language using the techniques and concepts ofcomputer science, the basic goal of which is to “teach”computers to generate and comprehendgrammatically-acceptable sentences., including:Machine translation – (MT) the use of computer software to translate texts fromone natural language to another. At its basic level, MTperforms simple substitution of words in one naturallanguage for words in another.(Computer-aided) corpus linguistics – dealing with the principles and practice ofusing corpora in language study. Usually, a computercorpus is a large body of machine-readable texts.1.1.3 Some Distinctions in LinguisticsThese distinctions can help to understand the difference between modern linguistics and the linguistics before the 20th century and to gain a general understanding of the nature of linguistic inquiry and the aims and approaches in linguistics.The beginning of modern linguistics is marked by the publication of F.de Saussure’s book “Course in General Linguistics”in the early 20th century. Before that language had been studied for centuries in Europe by such scholars as philosophers and grammarians. The general approach thus traditionally formed to the study of language over the years is roughly referred to as “traditional grammar”.Modern linguistics differs from traditional grammar in several basic ways.1.1.3.1 Prescriptive vs. Descriptive (p.3)---- purposes of prescriptive and descriptive linguistic studyPrescriptive: aim to lay down rules for “correct and standard”behavior in using language, i.e. to tell people what they should say and what they shouldnot say; prefer absolute standard of correctness; rely heavily on rules ofgrammarDescriptive: aim to describe and analyze the language people actually use, be it “correct” or not---- transfer of attention:Earlier study: prescriptive, based on “high”(religious. Literary) written language,setting models for language users to followModern linguistics: mostly descriptive, more scientific and objective ---- difference (divergence) of opinion1.1.3.2 Synchronic vs. Diachronic (p.4)---- concept of synchronic and diachronicSynchronic study: the description of a particular state of a language at a single point oftimeDiachronic study: the description of the historical development of a language over aperiod of time---- transfer of attention:In the 19th century: primarily of the diachronic descriptionIn the 20th century: the priority of the synchronic description over the diachronic onebecause without the successful study on the various states of alanguage in different historical periods, it would be difficult todescribe the changes that have taken place in its historicaldevelopment1.1.3.3 Speech vs. Writing (p.4)---- transfer of emphasis:Traditional grammarians: overstress the importance of the written wordModern linguists: regard the spoken language as primary and maintain that writing isessentially a means of representing speech in another medium ---- blurred distinction between speech and writing with modern technology Public speeches written in advance and read out orally;Chatting on internet while typing on the computer screen;Reading in the form of moving text, line following line up the screen1.1.3.4 Langue vs. Parole (p.4)---- proposed by the Swiss linguist F. de Saussure in the early 20th century---- concept of langue and paroleLangue Parole1) the abstract linguistic system shared by the realization of langue in actual useall the members of a speech community2) the set of conventions and rules which the concrete use of the conventions andlanguage users all have to abide by the application of the rules3) abstract, not the language people actually concrete, the naturally occurringuse language events4) relatively stable, do not change frequently vary from person to person, and fromsituation to situation---- transfer of attention in the linguistic study :langue parole in the latter part of the 20th century (recognizing varieties within languages, social and regional dialects, registers, styles, and so on) ---- objection to the distinction:Skinner from a strictly behavioristic point of view1.1.3.5 Competence vs. Performance (p.5)---- proposed by the American linguist Noam Chomsky in the late 1950’s and similar to Saussure’s distinction between langue and parole---- concept of competence and performanceCompetence: the ideal user’s knowledge of the rules of his languagePerformance: the actual realization of this knowledge in linguistic communicationAccording to Chomsky, a speaker has internalized a set of rules about his language,which enables him to produce and understand an infinitely large number of sentences and recognize sentences that are ungrammatical and ambiguous. Despite his perfectknowledge of his own langue, a speaker can still make mistakes in actual use, e.g.,slips of the tongue, and unnecessary pauses. This imperfect performance is caused by social and psychological factors such as stress, anxiety, and embarrassment.---- similar ideas possessed by Chomsky and SaussureBoth think that what linguists should study is the knowledge of language, langue orcompetence, the underlying system of rules that has been mastered by thespeaker-hearer. Although a speaker-hearer possesses the rules and applies them inactual use, he cannot tell exactly what these rules are. So the task of the linguists is to discover and specify these rules.---- difference between Chomsky’s distinction and Saussure’sSaussure: taking a sociological view of language and his notion of langue is socially shared, common knowledge, a matter of social conventions.Chomsky: examining language from a psychological point of view and competence isa psychological phenomenon, a genetic endowment in each individual, aproperty of the mind of each individual.1.1.3.6 Traditional grammar vs. Modern linguistics (p.5)◆modern linguistics ---descriptive;spoken language as primary ;not Latin-based framework◆traditional grammar ---prescriptive;written language as primary;Latin-based framework1.2 What is Language?1.2.1 Definitions of Languagep.7Some additional ones:Language is the most frequently used and most highly developed form of humancommunication we possess.语言是音义结合的词汇和语法的体系,是人类最重要的工具,是人类思维的工具,也是社会上传递信息的工具。

Linguistics语言学,the study of human language。

包括Theoretical linguistics,Applied linguistics,Sociolinguistics,Cognitive linguistics和Historical linguistics。