什么是欧洲主权债务违约风险-税收,CDS利差和市场定价风险

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:542.42 KB

- 文档页数:24

欧洲债务危机相关名词解释新华网布鲁塞尔7月21日电(记者刘晓燕崇大海)欧元区领导人21日召开特别峰会,就希腊新一轮救助计划达成协议。

下面是本次救助方案中涉及的一些相关名词。

一、债务违约(Default):债务人无法按照合同条款向债权人偿还债务。

二、选择性违约(SelectiveDefault):1、债务人不能完全履行全部债务条款,但违约仍处可控范围。

债权人与债务人达成协议,在部分违约情况下继续履行债务条约的其他条款。

2、标准普尔对主权债务的一个评级级别(SD),其级别在“违约”(D)级之上。

最新消息称,本次救助方案出台后,评级机构可能将希腊国债评级降至“选择性违约”(SD)级。

三、债务重组(DebtRestructuring):债权人按照其与债务人达成的协议同意债务人修改债务条款。

也就是说,只要修改了原定债务偿还条件的,均被视为债务重组。

一些专业人士指出,在本轮救助方案中,欧元区通过三种方式引入私人投资者(主要指银行)参与救助,实质上是对希腊债务实施重组。

四、债务展期(Rollover):本轮救助方案中私人投资者参与的一种方式,指在债务人出现偿债困难时,推迟债务到期时间。

比如,私人投资者“自愿”将持有的希腊国债到期时间延长至30年。

五、债务互换(Debtswap):本轮救助方案中私人投资者参与的一种方式,指希腊政府将发行新债券来替换私人投资者手中持有的国债,但新债的利率更低。

六、债务回购(Buyback):本轮救助方案中私人投资者参与的一种方式,指持有希腊国债的私人投资者可以将国债卖回给希腊政府,但出售价格将远低于债券的票面价格。

回购可以使希腊政府以更低成本削减债务。

七、欧洲金融稳定工具(EFSF):2010年5月,为了防止希腊债务危机蔓延,欧盟与国际货币基金组织设立了总额7500亿欧元(约合1.1万亿美元)的临时救助机制,其中由欧元区国家设立的“欧洲金融稳定工具”总额达4400亿欧元(约合6341亿美元)。

欧债危机,全称欧洲主权债务危机,是指自2009年以来在欧洲部分国家爆发的主权债务危机。

欧债危机是美国次贷危机的延续和深化,其本质原因是政府的债务负担超过了自身的承受范围,而引起的违约风险。

外部原因1 金融危机中政府加杠杆化使债务负担加重2 评级机构不断调低主权债务评级,助推危机进一步蔓延。

内部原因1,产业结构不平衡:实体经济空心化,经济发展脆弱2,人口结构不平衡:逐步进入老龄化3,刚性的社会福利制度4,法德等国在救援上的分歧令危机处于胶着状态根本原因1,货币制度与财政制度不能统一,协调成本过高。

2,欧盟各国劳动力无法自由流动,各国不同的公司税税率导致资本的流入,从而造成经济的泡沫化。

3,欧元区设计上没有退出机制,出现问题后协商成本很高。

高盛扮演角色:高盛公司为希腊量身定做的“货币掉期交易”方式,为希腊掩盖了一笔高达10亿欧元的公共债务,以符合欧元区成员国的标准。

有分析指出,高盛行为背后是欧美之间的金融主导权之争。

表面上来看,高盛在希腊债务危机中的角色是金融机构和主权国家之间的利益纠葛,但是从深层次来看,这是一种阻止欧洲一体化战略在经济上的表现。

解决途径第一,提高德国公共支出和预算赤字。

第二,扩大当前的7500亿欧元紧急救助基金规模。

第三,欧洲央行应扩大债券购买规模。

第四,“PIIGS”减少财政支出。

(1)实施紧缩的财政政策(2)申请和接受援助(3)组建技术性政府(4)发展经济(5)实施一揽子政策(6)缔结政府间条约欧洲债务危机对中国的影响三途径:贸易途径、金融途径、非接触性传导贸易途径:欧债危机造成的财政紧缩和消费萎缩、欧元贬值、贸易保护主义抬头是此次危机影响中国对外贸易主要因素。

金融途径:主要通过引发欧元资产贬值、短期投机资本流入和直接投资下降3个因素影响中国经济。

非接触性传导:事实上欧债危机还通过非接触性传导的途径影响中国经济。

具体说就是,欧债危机通过影响投资者信心,甚至引发“羊群效应”,给中国经济发展带来不利影响。

欧债危机详解欧债危机是指2009年欧洲各国债券风险升高,引发的一系列金融危机。

这场危机在欧元区内的许多国家经济遭受了严重的冲击,导致了欧洲经济的衰退和失业率的上升。

本文将详细解析欧债危机的原因、影响和应对措施。

首先,欧债危机的起因可以追溯到2008年的金融危机。

由于全球金融危机的冲击,许多国家的经济陷入衰退,政府为了刺激经济发展,采取了大规模的财政刺激政策。

然而,这导致了许多国家的债务水平不断上升,特别是在欧元区的一些国家,如希腊、葡萄牙、爱尔兰和西班牙等。

其次,欧债危机的爆发是由希腊危机引发的。

2009年,希腊政府公布了其财政赤字大幅超出预期的消息,这引发了国际市场对希腊债务可持续性的担忧。

由于希腊的债务水平高企,违约风险加大,国际投资者开始撤离该国债券市场,导致希腊的债务危机不断加深。

随后,市场开始担忧其他欧元区国家的债务风险,引发了欧债危机的全面爆发。

欧债危机对欧洲经济造成了严重的冲击。

首先,欧元区的许多国家在面临债务危机时,不得不实施紧缩政策,包括削减开支、提高税收等措施,这导致了这些国家的经济疲软和失业率的上升。

其次,欧洲金融市场遭受巨大冲击,许多银行和金融机构面临着流动性压力和信用风险。

最后,欧债危机引发了欧元区国家之间的信任危机,国家间合作和团结意识减弱,甚至有人担心欧元区解体的可能性。

面对欧债危机的挑战,欧洲各国采取了一系列应对措施。

首先,欧洲央行通过购买国债和提供流动性来稳定金融市场,避免系统性风险的发生。

其次,欧盟与国际货币基金组织共同提供了一揽子援助计划,为遭受债务危机的国家提供财政支持。

同时,各国政府也实施了结构性改革,为经济复苏创造条件。

此外,欧洲各国还加强了财政一体化和经济治理的合作,以加强对欧元区的监管和治理。

虽然欧债危机给欧洲经济带来了巨大的冲击,但各国的应对措施逐渐取得了一定效果。

欧洲各国的债务水平得到了逐步控制,财政状况有所改善。

同时,欧洲经济也出现了复苏的迹象,经济增长率逐渐回升,失业率有所下降。

欧洲债务危机即欧洲主权的债务危机。

其是指在2008年金融危机发生后,希腊等欧盟国家所发生的债务危机。

欧债危机概述欧洲主权债务危机爆发的主要引线或导火索可以说是希腊。

即希腊在2001年达到了欧盟的财赤率要求,同年加入欧元区。

但是,这一过程对希腊国家而言,所付出的代价也是相当巨大的。

具体而言,希腊为了尽可能缩减自身外币债务,与高盛签订了一个货币互换协议。

这样,希腊就通过货币互换协议减少了自身的外币债务,达到足够的财赤率加入欧元区。

但通过与高盛所签订的协议来看,希腊就必须在未来很长一段时间内支付给对方高于市价的高额回报。

随着时间的推移,希腊的赤字率显然会走入低迷状态,进而导致了2009 年的主权债务危机形成。

危机进程2011年11月28日,穆迪称,欧洲的债务危机正在威胁全部欧洲主权国家的信贷情况,意味即使Aaa评级的德国、法国、奥地利和荷兰都有危险。

2011年11月25日,穆迪下调匈牙利本外币债券评级一个级别至Ba1,是垃圾级中最高一级,前景展望负面。

该国目前在标准普尔和惠誉的评级均是投资级别中最低一级。

2011年11月25日,葡萄牙主权评级遭惠誉降至垃圾级别,即由BBB-调降1级至BB+,前景展望为负面。

2011年11月24日,法德领导人与新任意大利总理蒙蒂会面,商讨如何应对欧债危机。

德国总理默克尔依然坚持拒绝改变欧央行职能,并反对设立欧元区共同债券。

2011年11月23日,国际货币基金组织监于欧洲各国领导未能终止债务混乱状况,决定修改其信贷计划,鼓励面对外部风险的国家寻求只附带少数条件的IMF资金。

2011年11月23日,德国拍卖60亿欧元10年期国债,最终只出售六成,受消息拖累,德国债券遭市场抛售,10年期债息一度升至2。

26厘,2年多来首次超越英债。

表明随着危机扩散,欧元区已经没有零风险国债,唯一称得上零风险的只有瑞士国债。

2011年11月21日,欧盟委员会、欧洲央行及国际货币基金组织代表,在雅典与希腊最大的反对党新民主党领袖会谈时,未能劝服反对党领导人签署支持紧缩措施协议,令希债危机继续困扰金融市场,使得希腊在12月获批首轮第六笔80亿贷款存在变数,届时,金融市场将有新一波动荡。

欧债危机的解释欧债危机实质上是欧元区内国家间失衡所引发的国际收支危机。

由于各成员国在欧元区成立之初就已存在结构性差异,危机爆发前的十年间,“核心国家”生产、“边缘国家”消费的格局不断深化。

一旦从“核心国家”流向“边缘国家”的资金链条断裂,边缘国家的国际收支危机就被触发。

欧元区后路已断。

无论是核心国家还是边缘国家,都无法承受退出欧元区会带来的严重后果。

因此,欧元区解体对区内任何一个国家都不是一个选择。

欧元区已没有退路,不可能再退回到欧元出现之前的状况。

欧元区只有走向一体化,方能最终稳固。

欧元区需通过痛苦的结构改革,以及区内更加自由的产品和要素流动来消除国家间的失衡。

另外,还需要建成包括财政联盟在内的一系列一体化机制。

这一过程走下去,最终会让欧元区变成一个国家。

在这个过程中,欧央行会起关键作用。

在前行道路上,欧元区将长期处于危机和前进交替出现的状态。

由于政治推力和民意阻力之间的矛盾,通向一体化的道路就像是悬崖边的长征,征途上的危机恰恰是前行的动力。

因此欧元区将长期处于动荡。

这些动荡也是政治前进所必需的外在推动力。

1 债务危机只是表象欧债危机虽然被广泛的认为是一场主权债务危机,但它的病根并不在财政上。

危机前“欧猪五国”(葡萄牙、意大利、爱尔兰、希腊、西班牙)并非都国债高筑。

以次贷危机爆发前的2007年为例,整个欧元区财政赤字与国债余额占gdp的平均比重分别是0.6%和66.2%。

但边缘国家之一的爱尔兰在同年的财政预算却基本平衡,公债也只占gdp的25%。

同年西班牙的财政盈余甚至占到了gdp的1.9%,其债务余额也只有gdp 的36.1%。

美国、英国的国债水平与欧元区没有多大区别,日本的国债余额更是已经超过了其gdp的两倍,把欧元区远远抛在了后面,但这些国家也都没有爆发债务危机。

这样看来,财政问题并非欧债危机爆发并蔓延的根源。

欧央行的成立让欧元区国家的国债从无风险资产变成风险资产,因而容易受到攻击。

理论上来说,一个国家因掌握货币发行权,总能通过多发货币的方式来兑付其国债面值,因此国债没有信用风险,可被视为无风险资产。

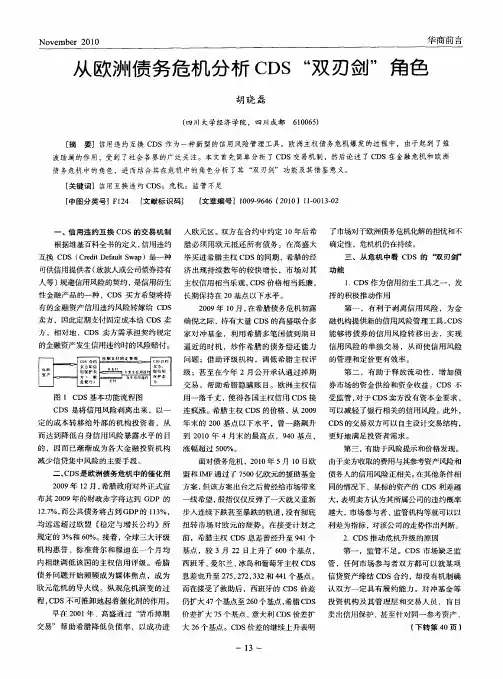

信用违约互换(CDS)定价模型与实证分析安泰11级金融硕士吴格【摘要】信用违约互换(CDS)作为重要的信用衍生工具,在近几年的美国次贷危机和欧债危机中均显示出其深刻的影响力。

由于发展时间相对较短、监管的不健全等因素,国际上的CDS市场也并不完善,业界对其的定价模型尚未形成统一定论。

特别是欧债危机中希腊等国家对其主权债务的清偿出现一定困难,致使其主权债CDS价差异常,也为CDS定价的理论模型带来挑战。

基于公司资产负债结构的结构化模型和基于外生违约强度的简约化模型各有优劣。

本文选取结构化模型中的CreditGrades模型和简约化模型中的Bloomberg模型,依据世界主要经济体的主权债CDS数据,对以上两类业界常用的定价模型进行实证分析。

从实质结果来看,虽然两者均能对CDS价差作出较为精准的估计,但是对于主权债CDS,CreditGrades模型由于其基础假设等原因,偏差较Bloomberg模型更大,而Bloomberg模型有虽然对市场信息依赖较大的特点,但在主权债CDS定价上更易发挥自身优势。

【关键词】信用违约互换;结构化模型;简约化模型一、研究问题作为全球范围内规模最大的信用衍生产品,信用违约互换(CDS)在美国的次贷危机和欧债危机中均显示出其深刻的影响力,但由于发展时间相对较短、监管的不健全等因素,国际上的CDS市场并不完善,市场上对于CDS的定价也并无统一定论。

尤其是欧债危机中希腊等国家对其主权债务的清偿出现一定困难,致使其主权债CDS价差异常,也为CDS定价的理论模型带来挑战。

1.背景意义信用违约互换(Credit Default Swap, CDS)又称信贷违约掉期,是目前全球交易最为广泛的场外信用衍生金融产品,其市值规模占全部信用衍生工具市场的97%以上。

信用违约互换兴起于20世纪90年代,它的出现解决了信用风险的流动性问题,使得信用风险可以像市场风险一样进行交易,从而转移担保方风险,同时也降低了企业发行债券的难度和成本。

欧洲主权债务危机与美国债务风险对比分析概述欧洲主权债务危机和美国债务风险是近年来国际经济领域中备受关注的两个热点问题。

欧洲主权债务危机是指希腊、意大利、西班牙、葡萄牙等欧洲国家的政府债务大规模逾期,导致欧洲金融体系遭受重创,整个欧洲经济也受到了影响。

而美国债务风险是指美国国债不断攀升,美国政府债务规模已经达到了历史上的最高水平。

本文将从债务规模、债务结构及债务问题解决方案等方面,对欧洲主权债务危机和美国债务风险进行对比分析。

债务规模欧洲主权债务危机欧洲主权债务危机是指欧洲债务危机爆发以来,欧洲各国的公共部门债务水平快速上升的现象。

其中希腊、意大利、西班牙、葡萄牙等国家的债务规模增速最快,债务占比也最高。

截至2019年末,欧元区的国内总产值为12.6万亿欧元,而欧元区的政府债务总额为10.3万亿欧元,占欧元区GDP的81.7%。

美国债务风险美国的国家债务也在不断攀升。

截至2021年1月底,美国国家债务总额已经达到了27.9万亿美元。

在过去10年中,美国的债务规模增长非常快,2010年底,美国债务总额仅为13.5万亿美元,而到了2020年,这个数字增长了近一倍。

截至2021年,美国的国防预算以及数十年的财政刺激政策,将进一步推高国家债务规模。

债务结构欧洲主权债务危机在欧洲主权债务危机中,欧元区国家通常有两种政府债务融资途径:国内融资和跨国融资。

国内融资主要是指政府向国内机构和个人借贷,包括债券融资和银行贷款;跨国融资则指政府向其他国家机构和国际金融机构借贷。

欧洲主权债务危机之所以恶化,部分原因也在于各国在债务融资中过度依赖国际金融市场,尤其是美国投资者。

美国债务风险美国的国家债务结构相对较为简单,绝大部分债务都由美国国内机构和个人持有,其中多数来自于政府创造的储蓄债券。

此外,美国国债还受到众多国际投资者的追捧。

债务问题解决方案欧洲主权债务危机欧洲国家采取的主要措施主要包括:财政调整措施、经济增长政策、金融市场自我纠正机制、欧盟各机构合作、国际机构介入等。

欧债危机的原因、影响、前景及解决对策一、概述全称为欧洲主权债务危机,是一场自2009年10月起逐渐在部分欧洲国家爆发的金融危机。

其根本原因在于这些国家政府无法及时履行对外债务偿付义务,导致国家资产负债表失衡,主权信用受到破坏。

这场危机不仅影响了欧洲国家的经济发展和社会稳定,也对全球经济产生了深远的冲击。

从原因上来看,欧债危机的爆发具有多方面的复杂性。

欧洲国家经济发展的不平衡、高福利政策带来的财政压力、货币政策与财政政策的不协调等因素都在其中起到了关键作用。

特别是在全球金融危机的背景下,欧洲国家的债务问题进一步加剧,最终导致了危机的全面爆发。

在影响方面,欧债危机对欧洲乃至全球经济产生了广泛而深刻的影响。

它导致了欧元区国家经济增长放缓,财政状况恶化,同时也引发了社会问题和政治动荡。

欧债危机还对全球金融市场产生了强烈的冲击波,股市、汇市和债券市场都受到了不同程度的冲击。

更重要的是,欧债危机还影响了国际贸易,使得贸易保护主义抬头,全球贸易增速放缓。

对于欧债危机的前景,各方观点不一。

有乐观派认为欧洲国家会采取有效措施解决债务问题,实现经济复苏;也有悲观派认为欧债危机将持续恶化,引发全球金融动荡。

多数观点认为,欧债危机的解决需要各方共同努力,加强政策协调,提供必要的支持和援助。

为了应对欧债危机,各国需要采取切实有效的对策。

这包括加强财政整顿,降低债务成本,实施相应的经济增长战略,以及建立更加协调的财政政策与货币政策机制。

全球各国也应加强合作,共同应对欧债危机对全球经济带来的挑战。

欧债危机是一场复杂且严重的经济事件,其原因、影响和前景都具有多方面的复杂性。

只有通过深入分析和研究,我们才能更好地理解这场危机,从而采取有效的对策来应对其带来的挑战。

1. 简述欧债危机的背景及概况又称欧洲主权债务危机,是一场始于2009年的重大经济危机。

其背景源于全球金融危机的余波未平,而欧洲部分国家因长期积累的财政赤字和国债问题,导致主权债务风险凸显,进而引发了市场对这些国家偿债能力的广泛担忧。

欧洲主权债务危机与金融市场变动分析自2009年欧元区爆发主权债务危机以来,欧洲的金融市场一直处于不断变动的状态。

各国政府、银行、投资机构都在挣扎着应对这场危机,而这场危机又成为了全球经济的一个重要因素。

本文旨在分析欧洲主权债务危机以及与之相关的金融市场变动,从中探讨其中的原因和影响。

一、欧洲主权债务危机的原因欧洲主权债务危机的根源在于欧元区的制度设计缺陷。

欧元区是由独立国家组成的货币联盟,各国之间存在着较大的经济发展水平差异,而欧元区并没有建立起相应的财政机制来实现经济政策协调。

加之2008年全球金融危机的影响,欧元区各国的财政状况急转直下,一些国家的财政赤字和债务水平迅速攀升,导致了主权债务危机的爆发。

具体来讲,欧元区各国的财政状况是主权债务危机的主要诱因。

随着全球经济危机的爆发,欧元区的经济也开始滑坡,使得许多欧洲国家的财政压力加大。

同时,欧洲各国政府为了打造自己的竞争力和吸引外资,采取了许多财政刺激措施,导致了财政赤字和债务的大幅增加。

另外,欧洲的银行体系也加剧了主权债务危机。

欧洲的银行普遍存在着过度杠杆化的问题,银行投资大量的委托人才能得到高的收益,而这些投资中一定程度上投向了许多欧洲国家的主权债券,让欧洲国家的主权债务问题愈发复杂。

二、欧洲主权债务危机的影响主权债务危机的爆发对欧洲的宏观经济和金融市场造成了深远的影响。

首先,主权债务危机对欧元区的整体实体经济造成了不可逆转的影响。

主权债务危机的爆发导致了欧元区经济的严重萎缩和高失业率,势必影响到居民消费和生活水平。

其次,主权债务危机也对欧洲的金融市场造成了冲击,导致股市、债市和货币市场大幅波动。

由于多数欧洲国家债务受到质疑,资本市场中资金流动性增强,出现了债券收益率与其风险挂钩的情况,风险扩散导致金融危机的扩散,从而导致了欧洲股市、债市和货币市场的暴跌。

除此之外,欧洲主权债务危机还对全球经济造成了一定的影响,导致诸多金融机构的倒闭和全球股市的剧烈波动。

cds的名词解释近年来,CDS(信用违约掉期)作为金融领域的一个重要概念逐渐走入公众视野。

然而,对于非专业人士来说,CDS的具体含义可能不太清晰。

在本文中,将对CDS进行详细解释,并探讨其在金融市场中的作用和影响。

一、CDS的定义和基本原理CDS是Credit Default Swap的缩写,即信用违约掉期。

它是一种金融衍生品,是由两方当事人之间签订的一份合约。

其中一方通常是投资者(通常为风险承受者),另一方则是银行或金融机构(通常为风险转移者)。

CDS的基本原理是,风险承受者向风险转移者支付一定的费用,以获取对某一特定债券或债务相关资产违约风险的保护。

二、CDS的作用和意义1. 风险管理工具CDS作为一种风险管理工具,可以帮助投资者降低持有债务资产时的风险。

通过购买CDS,投资者可以在债券违约时获得违约偿付。

这对于那些担心特定债券违约风险的投资者来说,特别有吸引力。

通过CDS,投资者可以将这种风险转移给其他有能力承担的机构,从而规避潜在的损失。

2. 市场流动性提供者CDS也可以作为市场流动性提供者的角色。

在某些情况下,市场参与者可能需要迅速调整其信用风险暴露,而CDS交易所提供的即时流动性可以帮助他们更灵活地管理风险。

这在金融市场中具有重要意义,特别是在金融危机期间,CDS提供了一种有利于市场平稳运行的机制。

3. 信用评级机构辅助工具CDS还可以作为信用评级机构的辅助工具。

信用评级机构通常根据债务人的信用状况评估债券的风险,然后给予相应的信用评级。

而在实际操作中,CDS交易数据也成为评级机构评估债务人信用状况的一个重要参考。

通过监测CDS交易活动,评级机构可以更准确地评估债券的风险水平,提高信用评级的准确性。

三、CDS市场的现状和挑战CDS市场在全球范围内发展迅速,成为金融市场中的重要组成部分。

然而,随着CDS市场规模的不断扩大,也引发了一系列潜在的问题和挑战。

1. 风险集中度CDS市场存在着一定程度的风险集中度。

欧洲债务危机即欧洲主权的债务危机。

其是指在2008年金融危机发生后,希腊等欧盟国家所发生的债务危机。

主权债务是指一国以自己的主权为担保向外,不管是向国际货币基金组织还是向世界银行,还是向其他国家借来的债务主权信用评级体现一国的可能性,评级机构依照一定的程序和方法对主权机构(通常是主权国家)的政治、经济和信用等级进行评定,并用一定的符号来表示评级结果。

主权评级涉及的内容很广,除了考虑GDP的增长趋势、对外贸易、国际收支情况、外汇储备、外债总量及结构、财政收支、政策实施等影响国家偿还能力的因素,还要对金融体制改革、国企改革、社会保障体制改革所造成的财政负担进行分析。

根据国际惯例,该国境内单位发行外币债券的评级上限,不得超过国家主权等级。

主权信用评级一般从高到低分为AAA,AA,A,BBB,BB,B,CCC,CC,C。

AA级至CCC级可用+号和-号,分别表示强弱。

三大评级公司是指:美国标准普尔公司、穆迪投资服务公司、惠誉国际信用评级有限公司。

三家评级机构各有侧重,标准普尔侧重于企业评级方面,穆迪侧重于机构融资方面,而惠誉更侧重于金融机构的评级成因去年10月初,希腊政府突然宣布,2009年政府财政赤字和公共债务占国内生产总值的比例预计将分别达到12.7%和113%,远超欧盟《稳定与增长公约》规定的3%和60%的上限。

鉴于希腊政府财政状况显著恶化,全球三大信用评级机构惠誉、标准普尔和穆迪相继调低希腊主权信用评级,希腊债务危机正式拉开序幕。

随着主权信用评级被降低,希腊政府的借贷成本大幅提高。

从目前的情况看,希腊政府必须在2010年紧急筹措540亿欧元资金,否则将面临破产“威胁”。

除希腊外,目前处于欧洲债务负担重灾区的葡萄牙、爱尔兰和西班牙等国的财政状况也引起投资者关注,意大利、比利时等国的主权信用也受到投资者广泛猜疑。

受此影响,从今年1月下旬开始,全球主要金融市场再度出现动荡,其中纽约股市道琼斯30种工业股票平均价格指数近来一度跌破万点大关。

欧洲主权债务危机的原因、模式及启示欧洲主权债务危机是以主权债务危机形式出现,它起源于国家信用,是政府的资产负债表出现问题从而产生的危机。

欧洲国家主权债务危机的出现有其历史、体制和自身原因,但最根本原因是这些国家经济失去了“生产性”。

欧洲主权债务危机的发生和演进不仅给后危机时代全球经济复苏带来了严峻挑战,也提醒各主权国家应该对政府债务问题给予足够重视和警惕。

中国中央政府债务虽然远在警戒线之下,但是庞大隐形地方政府债务问题不容忽视,目前地方政府债务风险实际上已经很大,成为威胁国家经济安全与社会稳定的首要因素。

有必要从严控制地方政府原始举债规模、降低地方债务违约率、加强逾期债务清偿能力三方面对地方政府债务风险进行有效防控。

一.欧洲债务危机发生的原因欧洲债务危机发生前,对于欧元启动以后的规定有两条,一条在制度设计上,总债务不能超过GDP 的60%,财政支出不能超过GDP 的3%。

但是现在来看,欧元区这些国家绝大多数都突破了这个界限,总债务占GDP 的比重大大超过60%,像意大利这样老牌的欧盟国家甚至已经超过了一倍,而导致欧洲债务危机发生的原因又是什么呢?首先,债务危机引发经济衰退,为了应对衰退,扩大政府支出是必然选择,支出扩大,而财政收入有限甚至是负增长将直接导致这些国家收支失衡,同时,政府对债务提高的警惕性较差,缺乏明确合理的财政计划,使得债务不断深化,最后才引发危机。

其次,欧洲发达国家的福利保障相对于发展中国家来说过高,这是引发债务危机的根本原因。

据统计,欧洲发达国家的福利清军占到了GDP的30%,这无疑提高了财政赤字。

过于丰厚的福利制度会降低劳动力的积极性,导致劳动力市场僵化,创新增长缓慢,公共债务居高不下,从而导致债务危机。

再者,制度是极度缺陷,在欧元区里面超国家主义的权力统一的货币政策和拥有主权的财政政策的予值,设计的缺陷导致可能在经济不景气的时候,遇到其他债务就发生危机。

最后,发展水平参差不齐。

欧洲主权债务危机的形成机理及警示引言欧洲主权债务危机是指一系列欧洲国家的主权债务违约和经济困境所引发的一场深层次危机。

该危机始于2009年希腊爆发的债务危机,随后波及欧元区其他国家,最终影响到整个欧洲和世界范围。

本文将从形成机理和警示角度探讨欧洲主权债务危机。

1. 形成机理欧洲主权债务危机的形成机理是多方面的,主要原因可以分为以下几个方面:1.1 资本流动和金融一体化欧洲的资本市场一体化以及金融自由化政策加速了资本流动,使得欧洲各国之间的金融联系更为紧密。

然而,这种紧密联系也增加了风险传导的可能性。

当一个国家陷入经济困境时,其债务问题很容易扩散到其他国家,导致整个地区陷入危机。

1.2 财政政策失调和结构性问题一些欧洲国家在长期以来的财政政策中存在严重失调,财政赤字和债务水平居高不下。

此外,一些国家还存在结构性问题,如过度依赖特定产业、低效的公共部门等。

这些问题使得这些国家在经济危机来临时更加脆弱,无法有效应对。

1.3 欧元区设计缺陷欧元区的设计缺陷也是欧洲主权债务危机的重要原因之一。

欧元区内各个成员国虽然使用统一货币,但缺乏足够的经济一体化措施。

这导致了货币政策和财政政策的脱钩,在危机时无法采取有效的整体性行动。

2. 影响和警示欧洲主权债务危机对欧洲和全球经济造成了深远的影响,同时给我们带来了以下几点警示:2.1 财务可持续性的重要性欧洲主权债务危机表明,财务可持续性是一个国家经济稳定和发展的基石。

国家应制定合理的财政政策,控制债务水平,避免财政失衡和债务问题的积累。

2.2 经济结构调整的必要性欧洲主权债务危机揭示了一些国家存在的结构性问题。

国家应推动经济结构调整,降低对某些行业的过度依赖,提升经济的自主性和韧性。

2.3 经济和金融风险传导的风险欧洲主权债务危机证明了金融市场中风险传导的快速性和广泛性。

国际金融市场需更加重视风险管理,增强金融体系的韧性,避免金融风险的蔓延。

2.4 欧元区设计和对外治理的重要性欧洲主权债务危机使人们重新审视欧元区设计的合理性和对外治理能力。

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier.The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use,including for instruction at the authors institutionand sharing with colleagues.Other uses,including reproduction and distribution,or selling or licensing copies,or posting to personal,institutional or third partywebsites are prohibited.In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of thearticle(e.g.in Word or Tex form)to their personal website orinstitutional repository.Authors requiring further informationregarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies areencouraged to visit:/copyrightAuthor's personal copyWhat is the risk of European sovereign debt defaults?Fiscal space,CDS spreads and market pricing of risk qJoshua Aizenman a ,*,Michael Hutchison b ,Yothin Jinjarak caRobert R.and Katheryn A.Dockson Chair in Economics and International Relations,USC,Los Angeles,CA 90089,USA bDepartment of Economics,UC Santa Cruz,Santa Cruz,CA 95064,USA cDeFiMS,SOAS,University of London,London WC1H0XG,UKJEL classi fications:E43F30G01H631Keywords:CDS spreads Sovereign risk Fiscal space Default risk Eurozonea b s t r a c tWe estimate the pricing of sovereign risk for fifty countries based on fiscal space (debt/tax;de ficits/tax)and other economic funda-mentals over 2005–10.We focus in particular on five countries in the South-West Eurozone Periphery,Greece,Ireland,Italy,Portugal and Spain.Dynamic panel estimates show that fiscal space and other macroeconomic factors are statistically and economically important determinants of sovereign risk.However,risk-pricing of the Eurozone Periphery countries is not predicted accurately either in-sample or out-of-sample:unpredicted high spreads are evident during global crisis period,especially in 2010when the sovereign debt crisis swept over the periphery area.We match the periphery group with five middle income countries outside Europe that were closest in terms of fiscal space during the European fiscal crisis.Eurozone Periphery default risk is priced much higher than the matched countries in 2010,even allowing for differences in fundamentals.One interpretation is that these economies switched to a “pessimistic ”self-ful filling expectational equilibrium.An alternative interpretation is that the market prices not on currentq We thank seminar participants at the Bank for International Settlements,Danmarks Nationalbank,the Bank of Canada,Columbia –Tsinghua international economics workshop,Chulalongkorn University (Sasin),Association for Public Economic Theory 2011Conference,and the National Institute for Public Finance and Policy 9th Research Meeting (New Delhi,India,2012)for very helpful comments.We also thank participants at the conference “The European Sovereign Debt Crisis:Background and Perspectives ”(Bank of Denmark,Copenhagen,April 3–4,2012),and especially our discussant,Marcus Miller,for helpful comments.*Corresponding author.E-mail address:aizenman@ (J.Aizenman).Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirectJournal of International Moneyand Financejournal homepage :www.else /locate/jimf0261-5606/$–see front matter Ó2012Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved./10.1016/j.jimon fin.2012.11.011Journal of International Money and Finance 34(2013)37–59Author's personal copybut future fundamentals,expecting adjustment challenges in the Eurozone periphery to be more dif ficult for than the matched group of middle-income countries because of exchange rate and monetary constraints.Ó2012Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.1.IntroductionDuring 2000–2006,the OECD and most emerging markets experienced a remarkable decline in macroeconomic volatility and the price of risk.This period turned out to be the tail-end of the Great Moderation ,a precursor of the turbulences leading to the global financial crisis of 2008–09,the consequent increase in risk premia,and the focus on fiscal challenges and the importance of fiscal space in navigating future economic challenges.The latter stages of the crisis,unfolding in 2010,focused attention on the heterogeneity of the Euro block,and the unique challenges facing the five South-West Eurozone Periphery countries,or SWEAP group (Greece,Ireland,Italy,Portugal,and Spain),in adjusting to fiscal fragility in the context of a ten-year old currency union.1This paper investigates the pricing of risk associated with the sovereign debt crisis that escalated during 2010in several European countries,and culminating in the selective default on Greek sovereign debt in early 2012.Our objective is to determine whether the perception of relatively high sovereign default risk of the fiscally distressed Euro area countries,as seen in market pricing of credit default swap (CDS)spreads,may be explained by existing past or current fundamentals of debt and de ficits relative to tax revenues –which we term de facto fiscal space –and other economic determinants.2Our analysis allows us to address several questions.Does fiscal space help systematically explain the evolution of the market pricing of risk beyond that embedded in other macroeconomic indicators?Was risk in some markets (e.g.SWEAP)“overpriced ”in 2010judging by model predictions using the pre-vailing values of fiscal space other macro variables?Our objectives for the empirical work are three-fold.Firstly,we determine whether CDS spreads (in a panel regression setting)are related to fiscal space measures and other economic determinants.Secondly,we address whether there is an identi fiable dynamic pattern to CDS spreads during the crisis period.Thirdly,we investigate pricing differentials of CDS spreads in the Euro area,and the SWEAP in particular,compared to other countries.We seek to answer the question of whether Euro area and SWEAP CDS spreads follow the same pattern as the rest of the world or may they considered “mis-priced ”in some sense,especially during the 2010European debt crisis.To this end,we develop a pricing model of sovereign risk for a large number of countries (50)within and outside of Europe,before and after the global financial crisis,based on fiscal space and other economic fundamentals including the foreign interest rate,external debt,trade openness,nominal depreciation,in flation,GDP/Capita and economic growth.We use this dynamic panel model to explain CDS spreads and determine whether the market pricing of risk is comparable in the affected European countries and elsewhere in the world.By this methodology,and using in-sample and out-of-sample predictions,we can determine whether there are systematically large prediction errors for the CDS spreads during the global financial crisis and in 2010when the sovereign debt crisis in Europe intensi fied.Systematically large prediction errors may be due to mispricing of risk or may be attrib-utable to expectations of a future decline in fundamentals that lead to higher default risk.We also “match,”on the basis of similar fiscal space,each SWEAP country with a corresponding Middle Income country.This provides additional information on the market pricing of risk between SWEAP and countries with similar fiscal conditions but,unlike SWEAP,with histories of debt restructuring.1The SWEAP acronym for these five countries is used in Buiter and Rahbari (2010).2Our measure of fiscal space is from Aizenman and Jinjarak (2010).They propose a stock and flow measure of de facto fiscal space.The stock variable is de fined as the inverse of the tax-years it would take to repay the public debt.In this paper,fiscal space is measured both as outstanding government debt and government de ficits,relative to the de facto tax base.The de ficits measure is the realized tax collection,averaged across several years to smooth for business cycle fluctuations.J.Aizenman et al./Journal of International Money and Finance 34(2013)37–5938Author's personal copyJ.Aizenman et al./Journal of International Money and Finance34(2013)37–5939 Our investigation reveals a complex and time-varying environment in the market for sovereign default risk.Specifically,wefind empirically a key role offiscal space in pricing sovereign risk, controlling for other relevant macro variables.The link is economically and statistically strong,and robust to the time dimension of the CDS premium,sample period,included control variables and estimation technique.Wefind that risk of default in the SWEAP group appeared to be somewhat “underpriced”relative to international norms in the period prior to the globalfinancial crisis and substantially“overpriced”countries during and after the crisis,especially in2010,with actual CDS values much higher than the model would predict given fundamentals.In addition,compared to the matched group,controlling forfiscal space and macroeconomic conditions,all of the SWEAP countries have much higher default risk assessments measured by CDS premiums.One potential explanation for the switch from under-to over-pricing of default risk is that markets were forward looking,not pricing entirely on current fundamentals but on expected further deterioration in future SWEAP fundamentals, especially in the realm offiscal space.Alternatively,the results are consistent with multiple equilib-rium with an abrupt switch from a“good”(optimistic)expectations equilibrium in the Euro Area–with low expected default rates and low interest rates wherefiscal positions are sustainable–to a“bad”(pessimistic)expectations equilibrium in these same countries–with high expected default rates and high interest rates wherefiscal positions are not sustainable.The next section discusses the data.The third section provides a preliminary statistical analysis.The fourth section presents the empirical results.We close the paper with a discussion on possible inter-pretation of the emerging SWEAP risk premia,including the handicapping effect of being a member of a currency union,which reduces the country’s scope of adjustment via exchange rate and monetary policy.2.CDS spreads as a measure of sovereign default risk2.1.CDS spreads on sovereign bondsWe measure the market perception of sovereign default risk by the spreads on sovereign credit default swaps(CDS)at various maturities(tenors).3CDS instruments are mainly transacted in over-the-counter(OTC)derivative markets.The spreads represent the quarterly payments that must be paid by the buyer of CDS to the seller for the contingent claim in the case of a credit event,in this case non-payment(or forced restructuring)of sovereign debt,and is therefore an excellent proxy for market-based default risk pricing.4The total CDS market grew from about10trillion USD in2004,when statistics werefirst systematically reported,to a peak prior to the globalfinancial crisis of almost60 trillion USD in mid-2008,and then fell sharply.The estimated gross(net)notional amount of sovereign CDS outstanding was2447(233)billion USD in2010,compared to about2196billion USD in government-issued international debt securities(BIS,2010).Fig.1shows the outstanding notional amounts of CDS instruments on sovereign bonds across countries in late February2011.Italy has the largest outstanding CDS notional amounts,at almost USD300billion,followed by Brazil,Spain and Turkey with notional amounts outstanding of over USD150billion.Sovereign CDS provide a market-based realtime indicator of sovereign credit quality and default risk.We consider sovereign CDS spreads at several maturities d three,five and ten-year maturities, across industrial countries and emerging markets.Despite the low probability of a credit event in most advanced economies,CDS markets are still active in most markets as buyers can use the sovereign CDS3See Packer and Suthiphongchai(2003)and Fontana and Scheicher(2010)for discussions of sovereign CDS markets.4An alternative proxy for default risk is the interest rate spread of sovereign debt.From an empirical standpoint,there are three main advantages of using CDS spreads rather than interest rate spreads.Firstly,CDS statistics provide timelier market-based pricing with larger coverage of industrial and developing countries than sources for national bond market rates. Secondly,using CDS spreads avoids the difficulty in dealing with time to maturity as in the case of using interest rate spreads(of which the zero yields would be preferred).Recent estimates from the Bank for International Settlements suggest that the average original and the remaining maturities of government debt instruments vary markedly across countries(BIS,2010). Thirdly,interest rate spreads embed inflation expectations and demand/supply for credit conditions as well as default risk.We are only interested in default risk.Author's personal copyas a hedge and for mark-to-market response.5Buyers of the sovereign CDS may or may not own the underlying government bonds.The latter case is termed ‘naked ’sovereign CDS,and frequently labeled as a speculation.CDS prices in our study are taken from CMA Datavision,a platform that is based on quotes collected from a consortium of over thirty independent swap market participants.CMA aggregates the most recent quotes and delivers the data intraday.The quoting convention for CDSs is the annual premium payment as a percentage of the notional amount of the reference obligation.The sovereign CDS spreads are reported in basis points,with a basis point equals to $1000to insure $10million of debt.6CDS spreads are London closing values.While CMA is not the sole provider of CDS prices,Mayordomo et al.(2010)find that,in a comparison of six major providers,CMA quotes are most consistent with a price discovery process.The majority of sovereign CDS in the market are denominated in the US dollar;in our sample,about one-third of the CDS is Euro-denominated.The CMA data set provides a broad coverage of CDS pricing over countries and years.Appendix A provides data sources and Appendix B a list of countries in the entire sample,the subset of countries included in the empirical estimation,and means of 3,5and 10-year CDS spreads (in basis points),fiscal space and other macroeconomic indicators during the sample (2005–10).2.2.Empirical studies on CDS spreadsEmpirical studies of CDS (corporate and sovereign)are relatively new and usually deal with market microstructure issues.Our study,by contrast,is in line with the macro/international finance literature which considers macroeconomic determinants of country risk assessments and financial crises.Several findings are particularly relevant to our analysis.As noted by Packer and Suthiphongchai (2003)and others,the CDS premium should in principle be approximately equal to the credit spread10020030A R G c d s A U S c d s A U T c d sB E L c d s B G R c d s B R A c d sC H L c d s C H N c d s C O L c d s C Z E c d sDE U c d s D N K c d s E S P c d s E S T c d sF I N c d s F R A c d sG B R c d s G R C c d sH R V c d s H U N c d sI D N c d s I R L c d s I S L c d s I S R c d s I T A c d sJ P N c d sK A Z c d s K O R c d sL B N c d s L T U c d s L V A c d sM E X c d s M Y S c d sN L D c d s NO R c d s N Z L c d sP A N c d s P E R c d s P H L c d s P O L c d s P R T c d sQ A T c d sR O M c d s R US c d s S V K c d s S V N c d s S W E c d sT H A c d s TU N c d s T U R c d s U K R c d s U S A c d sV E N c d s V N M c d s Z A F c d sFig.1.Global sovereign CDS positions in early 2011.This figure provides the gross notional amount of outstanding sovereign CDS positions (billion US$)as of February 25,2011.Source:Depository Trust &Clearing Corporation (DTCC).5Sovereign CDS can also be used to supplement corporate CDS to hedge for country risk.6For example,if the spread is 197basis points,meaning 197,000USD to insure against 10,000,000in sovereign debt for 10years;1.97%of notional amount needs to be paid each year,so 0.0197Â10million ¼$197,000per year.J.Aizenman et al./Journal of International Money and Finance 34(2013)37–5940Author's personal copyJ.Aizenman et al./Journal of International Money and Finance34(2013)37–5941 of the reference bond of the same maturity under certain conditions.However,Fontana and Scheicher (2010)demonstrate that the“basis”,i.e.difference between CDS spreads and the spreads on the underlying government bonds,was not zero in Eurozone CDS markets during late2010.They suggest that sizable deviations are attributable to limits to arbitrage and slow moving capital.Secondly,at high frequency(intraday),differences in credit quality(measured by CDS prices)are found to explain sovereign yield spreads of the Euro area governments(Beber et al.,2009).7Fontana and Scheicher (2010)argue that high CDS premium in late2010during the Eurozone debt crisis may be partly attributable to a decline in the appetite for credit-risky instruments and falling market liquidity rather than entirely due concerns about principle losses on outstanding sovereign debt.In addition,empirical researchfinds that daily sovereign interest spreads are more likely to lead sovereign CDS spreads in emerging markets(Ammer and Cai,2007).8Taken together,both studies suggest that sovereign interest rates and CDS spreads have common underlying causes,rather than one driving the other.This is consistent with other work where some studies indicate that price discoveryfirst occurs in the CDS market and follows in the bond market,and vice versa.9There is evidence that CDS spreads may be driven by macroeconomic conditions.Amato(2005) decomposes CDS spreads into risk premium and risk aversion andfinds that both are influenced by macroeconomic conditions.Packer and Zhu(2005)find that contractual terms influence CDS spreads, but that significant“regional effects”(differential pricing across regions)is also evident.Micu et al. (2006)alsofind that credit rating announcements have a large influence on CDS spreads.In explain-ing recent developments,Berndt and Obreja(2010)suggest that“economic catastrophe risk”rose sharply in2007–08pushing up CDS spreads.Cecchetti et al.(2010)plot severalfiscal indicators against CDS spreads for advanced economies.Theyfind correlations across countries with substantial hetero-geneity.10Longstaff et al.(2011)study sovereign CDS of several emerging markets from October2000to January2010.They found that the sovereign spreads are more associated with global factors(US stock, treasury,and high yield markets)than local factors(stock return,exchange rate,and foreign reserve). Dooley and Hutchison(2009)find thatfinancial,economic and regulatory“news”emanating from the U.S.during the globalfinancial crisis quickly impacted sovereign CDS spreads in emerging markets.Concerns about price determination,systemic risk to thefinancial system,and the general opacity of the over-the-counter markets(where CDS is now traded)have led to calls more government regulation and for CDS to be traded on organized exchanges.Presently CDSs are not traded on an exchange and there is no required reporting of transactions to a government agency.One reason for the traditionally limited government oversight is that OTC markets are considered wholesale markets for professional participants,rather than retail investors.However,the recentfinancial turmoil has shown that OTC derivative markets can negatively affect other functioningfinancial markets and can be a serious risk to the health of the banking system.These observations have led to increasing calls for the regulation and oversight CDS markets.For example,in the event that regulatory reforms require that CDS be traded and settled via a central exchange/clearing house,there would no longer be‘counter-party risk’,as the risk of the counterparty will be held with the central exchange/clearing house.113.Statistical contoursMonthly5-year CDS spreads from2005to2011are plotted for the SWEAP and other selected countries(countries which are matched with the SWEAP group,discussed below)in Fig.2.Judging by7Beber et al.study microstructure data of bond quotes and transactions from the interdealer markets,covering Austria, Belgium,Finland,France Germany Greece,Italy,Netherlands,Portugal and Spain.Their sample period is April2003–December 2004.8Ammer and Cai examine daily data from February2001to March2005,covering Brazil,China,Colombia,Mexico, Philippines,Turkey,and Uruguay.On interest rates,CDS spreads,and speculation,see also the discussion offindings from the European Commission(Tait and Oakley,2010),which suggests no strong causality between the two.9See Carboni(2011)for a recent review of the empirical literature on this point.10For example,they plot the forecast level of general government debt/GDP against January2010CDS spreads for21 advanced economies andfind a positive correlation.11Kiff et al.(2009)discuss systemic risk and calls and government regulation policy options in the CDS market.Author's personal copythese spreads,financial stress in global markets emerged in early 2008but became dramatic and widespread in late 2008.The turbulence subsided by mid-2009in most countries,with the notable exception of the SWEAP group:Greece,Ireland,Italy,Portugal,and Spain.For Greece,the unraveling of its fiscal condition in late 2009resulted in a manifold increase in sovereign CDS spreads.For Ireland,the sovereign CDS spreads have widen sharply twice,in early 2009and in late 2010.By 2010,spreads of the SWEAP group were already much higher than those of most emerging market countries (e.g.above the spreads of South Africa,Mexico,Panama,Malaysia and Colombia in Fig.2).On the other hand,sovereign spreads of Germany and the US remained very low throughout the period (not shown).Table 1reports the annual mean values (standard deviation in parentheses)of sovereign CDS spreads (5-year tenor),fiscal space and macroeconomic fundamentals for SWEAP and other country groupings.The table shows average values for the period before crisis (2005–07)and during the crisis (2008–10and individual years).The fall of 2008was the height of the global financial crisis,while the latter part of 2009was a recovery period as financial panic and the liquidity crisis subsided for most countries.However,the SWEAP sovereign debt crisis manifested mainly in 2010and later.Prior to the crisis,SWEAP CDS values were quite low,ranging from 8to 17basis points on average,which are somewhat but not markedly higher than the mean of other Euro countries (11basis points)and lower than the non-Euro OECD group (35basis points).During the early months into the global financial crisis,2008–09,sovereign CDS spreads rose in virtually every country.However,spreads dropped very substantially in all regions by 2010except for the Euro area excluding SWEAP,where it remained roughly unchanged,and SWEAP,where it rose dramatically.SWEAP CDS average values in 2010ranged from 238basis points in Italy to 1027basis points in Greece.By contrast,in 2010,OECD countries (non-Euro members)had an average CDS spread of 118basis points and non-SWEAP Euro members had an average spread of 101basis points.As our main objective is to investigate the link between fiscal space and the pricing of default risk,we also track the adjustment of fiscal capacity across countries.Table 1shows the fiscal balance to tax base ratio and the public debt to tax base ratio.OECD (excluding the Euro countries)and non-SWEAP Euro countries experienced an increase in debt/tax ratios by 0.2percent and 0.3percent,respectively,100200300400ESP100200300400ZAF02000400060008000GRC100200300400PAN0200400600800IRL050100150200250MYS0100200300400500ITA 0100200300400MEX500100015002005q42006q42007q42008q42009q42010q42011q4PRT1002003004002005q42006q42007q42008q42009q42010q42011q4COLFig.2.Evolution of sovereign CDS prices.This figure plots CDS 5-year tenor (basis points)for selected middle-income countries and Eurozone members.J.Aizenman et al./Journal of International Money and Finance 34(2013)37–5942Author's personal copyT a b l e 1S u m m a r y s t a t i s t i c s o f s o v e r e i g n C D S v a l u e s a n d f u n d a m e n t a l s .C o u n t r y S o v e r e i g n CD S 5-y r t e n o r (b a s i s p o i n t s )F i s c a l b a l a n c e /t a x b a s eP u b l i c d e b t /t a x b a s e05–0708091008–1005–0708091008–1005–0708091008–10S p a i n 16.7100.7113.5347.7187.30.05À0.12À0.31À0.27À0.231.11.11.51.71.4G r e e c e 15.0232.1283.41026.5514.0À0.18À0.29À0.48À0.33À0.373.23.54.04.54.0I r e l a n d 8.6181.0158.0619.2319.40.05À0.24À0.47À1.08À0.600.91.52.23.22.3I t a l y 13.4156.9109.2238.0168.0À0.07À0.07À0.13À0.11À0.102.52.52.82.82.7P o r t u g a l 10.496.391.7497.3228.4À0.13À0.11À0.30À0.27À0.221.91.92.22.42.2M i d d l e -i n c o m e g r o u p 124.2(102.8)829.9(1069.4)295.2(331.3)233.2(221.5)452.8(540.7)À0.06(0.2)À0.08(0.2)À0.22(0.2)À0.19(0.1)À0.16(0.2)2.7(2.6)2.2(2.1)2.3(1.9)2.3(1.9)2.3(2.0)H i g h -i n c o m e (n o n O E C D )32.1(13.9)330.7(158.9)164.0(90.5)172.3(118.4)222.3(122.6)0.13(0.4)0.24(0.5)0.10(0.4)0.16(0.5)0.17(0.5)1.2(0.8)1.0(0.6)1.7(0.1)1.4(0.8)1.4(0.5)O E C D (n o n E u r o )34.8(41.5)260.3(238.8)120.3(103.5)117.8(96.4)166.2(146.2)0.04(0.2)0.01(0.2)À0.12(0.1)À0.08(0.1)À0.06(0.1)1.7(1.7)1.7(1.7)1.9(1.8)1.9(1.8)1.8(1.8)E u r o (e x c l u d i n g S W E A P )11.0(13.3)95.1(40.2)54.2(24.6)101.3(55.2)83.5(40.0)À0.03(0.0)À0.02(0.0)À0.15(0.1)À0.14(0.1)À0.10(0.1)1.4(0.5)1.4(0.5)1.6(0.5)1.7(0.4)1.6(0.5)T r a d e /G D P I n fla t i o n (%)E x t e r n a l d e b t /G D P05–0708091008–1005–0708091008–1005–0708091008–10S p a i n 0.60.60.50.50.53.551.400.802.781.661.41.51.71.51.6G r e e c e 0.60.60.50.50.53.322.642.9717.347.651.31.41.81.71.7I r e l a n d 1.51.61.60.91.43.754.05À4.481.300.297.88.910.711.010.2I t a l y 0.60.60.50.60.52.302.261.022.101.791.11.01.21.11.1P o r t u g a l 0.70.80.60.70.72.600.710.002.521.081.91.92.32.42.2M i d d l e -i n c o m e g r o u p 0.9(0.5)0.9(0.5)0.8(0.4)0.9(0.5)0.9(0.4)6.74(4.7)9.73(6.8)5.24(5.9)6.61(5.4)7.19(6.0)0.5(0.3)0.4(0.3)0.4(0.3)0.4(0.2)0.4(0.3)H i g h -i n c o m e (n o n O E C D )0.9(0.0)0.9(0.1)0.8(0.0)0.8(0.0)0.8(0.0)8.20(6.2)8.02(7.3)À0.90(3.9)1.37(0.7)2.83(4.0)0.6(0.2)0.7(0.2)0.9(0.2)0.8(0.2)0.8(0.2)O E C D (n o n E u r o )0.8(0.3)0.9(0.4)0.8(0.3)0.8(0.4)0.8(0.4)3.38(2.3)4.60(3.4)3.02(3.5)3.08(1.4)3.57(2.8)1.0(1.1)1.3(2.0)1.5(2.5)1.5(2.4)1.4(2.3)E u r o (e x c l u d i n g S W E A P )1.2(0.4)1.3(0.4)1.2(0.5)1.2(0.4)1.2(0.4)2.56(1.0)2.13(1.1)0.94(0.5)2.05(0.6)1.71(0.7)1.8(1.0)1.8(0.9)2.0(0.9)1.9(0.9)1.9(0.9)T h i s t a b l e r e p o r t s m e a n a n d s t a n d a r d d e v i a t i o n (i n p a r e n t h e s i s )o f s o v e r e i g n C D S s p r e a d s (b a s i s p o i n t s )a n d m a c r o f u n d a m e n t a l s .T a x b a s e i s a n a v e r a g e t a x /G D P o v e r a p e r i o d o f p r e v i o u s 5y e a r s .A p p e n d i x A p r o v i d e s d a t a s o u r c e s a n d A p p e n d i x B d e t a i l s t h e c o u n t r y g r o u p s .J.Aizenman et al./Journal of International Money and Finance 34(2013)37–5943Author's personal copybetween 2005and 07and 2010.For Ireland and Greece,the deterioration in fiscal circumstances was much more drastic:the government debt of Ireland climbed from 25%of GDP in 2007to almost 100%of GDP in 2010,while the government debt of Greece grew from 95%to over 140%.As a result,the debt/tax ratio of Ireland jumped from 0.9to 3.2and that of Greece from 3.2to 4.5,leaving both countries with a much less room for a flexible policy response on the fiscal side.The large increase of debt/tax ratios in both countries captures a high degree of distress in their economic fundamentals,including the government assumption of banking sector liabilities in the case of Ireland.Similarly large deteriora-tions in fiscal space for these countries are also evident in the fall in fiscal balance to tax ratios.We illustrate further the 2005–07fiscal preconditions,as measured by debt/tax (and debt/gdp)and de ficit/tax (de ficit/gdp),in the two panels of Fig.3by country group.Lower pre-crisis government debt and lower fiscal de ficits relative to the tax base imply greater fiscal capacity.The figure shows that fiscal space was weakest (highest levels of debt and de ficits relative to the tax base)in the middle-incomecountries,although the average debt to gdp ratio was lower than the other groups.This re flectsgenerally lower tax bases in the middle income countries.Generally,the SWEAP had more limited fiscal space during the tranquil period than other high-income groups –higher average debt and de ficits to the relative to the tax base (despite a signi ficant budget surplus in Ireland during this period),and a higher level of debt to GDP.4.Methodology and empirical results 4.1.MethodologyThe dependent variables in our formal empirical work are sovereign CDS spreads of 5year maturity (regressions with 3and 10-year maturities are shown in the appendix table),12estimated in a panelregression,y it ¼a i þl t þq D y it À1þX 0it b þ3it ;where y is the CDS spread,i stands for country and t foryear;X is a vector of controls.The sample covers a panel of 50countries from 2005to 2010.The vector X includes fiscal space (government debt/tax and fiscal de ficit/tax)d the focus of our work d as well as several other variables that frequently employed in the literature to explain country risk.These variables are the TED spread,external debt (total foreign liabilities/GDP),trade openness (trade/GDP)and in flation.As the conditions for consistent estimation in the dynamic panel are known to be demanding,our solution is to work with both a simple fixed-effects model and other estimation speci fications,including clustered standard errors and the Arellano-Bond dynamic panel estimator.Arellano-Bond is a GMM estimator with instruments (exogenous and lagged values),well suited to the problem at hand,with a substantially larger number of cross-section units (50countries),but requires many period of data as the instruments to account for the correlation of lagged dependent variable and the unobserved error terms.We consider fixed effects,clustered standard errors,and GMM in several variants of the model as bounding the causal effects of interest.The sovereign spreads are estimated in level.We also consider for GMM the dependent variable in log multiplied by a hundred,allowing the coef ficients to be interpreted in terms of a percentage change of sovereign default risks (this terminology also aligns with standard practice in the financial sector that discusses the percentage change of CDS spreads).4.2.Dynamics of CDS spreads and Euro/SWEAP pricing differentialsTable 2considers the dynamics and structure of CDS pricing over the 2005–10sample period.Differential pricing for the SWEAP and other Eurozone countries (non-SWEAP)is investigated.To focus on CDS pricing dynamics during the global and European financial turmoil,we include time dummy variables (t 2008–t 2010)for three crisis years:2008is identi fied as the central part of the global financial crisis,2009is identi fied as a partial recovery period,and 2010is identi fied with the SWEAP12Our CDS data set contains 1–10year maturities.We focus on the 5-year maturity since this is the deepest and most actively traded CDS market.While there is no precise international account of government debt maturity,recent statistics suggest that the average original maturity of central government debts is around 10years for both emerging markets and industrial countries (BIS,2010).Hence,we also report results for 10-year maturities in the appendix,as well as 3-year maturities for a robustness test.J.Aizenman et al./Journal of International Money and Finance 34(2013)37–5944。