Does_investment_efficiency_improve_after_the_disclosure_of_material_weaknesses_in_internal_control

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:290.96 KB

- 文档页数:18

Improve Employee Productivity, Efficiency & SuccessIn the epic movie Ben Hur, Charlton Heston and his fellow slaves had to row a Roman galley in time with the beating of a drum. When they needed to row faster, the drummer would drum faster.Your business doesn't use drums to motivate employees, although that might be nice at times. Employees bring their own agendas with them and are only motivated to get as much work done as will benefit them. That's certainly not to suggest that employees don't work hard or try to advance, but there needs to be a tangible benefit to push them on.As you review your motivation tactics, look to see if you are rewarding them for completing a lot of good work or for just showing up.Your payment system is the first step in rewarding employee efficiency (or inefficiency). If you pay a salary without any other kind of incentive, you're inviting the possibility that the employee will only do the minimum amount required. After all, there is no reward for doing more.Instead, consider a reward for efficiency or an incentive to complete more. For example, if your employees can complete a week's worth of assigned work in just 4 days, they don't have to come in on Friday.Another additional incentive might be to tie a commission-based wage to the profitability of the company, giving them a sense of ownership.There's a (possibly) apocryphal account of doctors in ancient China who were paid not for the number of sick people they treated, but rather for the number of healthy people living in their territory. Regardless of whether this is true or not, it's a great example of shifting the focus of rewards and motivation to the work you actually want done.Beyond wages and motivational rewards, there are other ways to improve efficiency in your office. Here are some ideas:∙Make it a fun place. This will keep people's attitudes positive and they'll want to come to work.∙Be flexible with shifts. If possible, don't have everyone come in from 9-5 (or whatever your hours are). Offer employees otheroptions, including flextime (minimum of 8 hours worked in a 15 hour window), split shifts, or even work-at-home arrangements.These options often end up saving you money!∙Learn what your employees need on a regular basis and make it available to them. If many employees head down to thebuilding's cafeteria for a soft drink, why not put a vendingmachine right in your office? If employees leave their desk to use the office stapler, put a stapler on their desk.∙Use time tracking, collaboration, and project management software to keep everyone "on task" and aware of what they're doing and what they'll need to do next.∙Make people aware of the system and how they fit into it. Often, people under-perform when they don't realize that others arerelying on them. If they understand that they fit into a system like a gear in a clock, they'll contribute more for the sake of the team.∙Use a flowchart to track the workflow in your office. Are people touching papers or packages more than once? Is a documentgoing through unnecessary steps? If it's been a while since you reviewed your workflow, do it now because workflow canchange and become inefficient quickly, even if you initially set it up to be very efficient.。

高二英语金融理财单选题40题1.Which one is not a financial instrument?A.stockB.bondC.bookD.option答案:C。

book 不是金融工具,stock 是股票,bond 是债券,option 是期权,都属于金融工具。

2.If you want to invest in a company, you can buy its _____.A.sharesB.booksC.pensD.papers答案:A。

如果你想投资一家公司,可以买它的股票(shares)。

books 是书,pens 是笔,papers 是纸,都与投资公司无关。

3.A bond is a kind of _____.A.debt instrumentB.equity instrumentC.stationeryD.food答案:A。

债券是一种债务工具((debt instrument)。

equity instrument 是权益工具,stationery 是文具,food 是食物。

4.Which of the following is not a characteristic of stocks?A.High riskB.Low returnC.LiquidityD.Part ownership of a company答案:B。

股票的特点通常有高风险((High risk)、流动性((Liquidity)以及代表对公司的部分所有权((Part ownership of a company),而不是低回报(Low return)。

5.An option gives the holder the right to _____.A.buy or sell an assetB.read a bookC.eat an appleD.write a letter答案:A。

期权给予持有者买入或卖出一项资产的权利。

如何兼顾经济效率英文作文英文回答:Striking a balance between economic efficiency and equity is a multifaceted issue that requires a comprehensive approach. Here are some key strategies:Progressive taxation: Progressive tax systems, in which higher incomes are taxed at higher rates, can help redistribute wealth and create a more equitabledistribution of resources. This can reduce incomeinequality and provide funding for essential public services.Minimum wage laws: Minimum wage laws ensure that all workers earn a living wage, reducing income inequality and promoting economic stability. By setting a floor for wages, these laws can help reduce poverty and increase consumer spending, stimulating economic growth.Investment in education and training: Investing in education and training programs increases human capital and improves economic productivity. By providing individuals with the skills and knowledge they need to succeed in the workforce, governments can promote economic efficiency and create opportunities for higher-income earners.Social safety nets: Robust social safety nets, such as unemployment insurance, healthcare, and affordable housing, provide a cushion for vulnerable populations and reduce income inequality. By ensuring that everyone has access to essential services, governments can promote economic efficiency by stabilizing the labor market and reducing the economic burden of poverty.Regulation and competition: Well-designed regulation and competition policies can promote economic efficiency by preventing monopolies and fostering innovation. By ensuring that markets are competitive and open to new entrants, governments can encourage businesses to innovate and compete on price and quality, resulting in lower prices and higher-quality goods and services.中文回答:如何兼顾经济效率和公平性。

英语作文-金融资产管理公司加强数据分析能力,提升投资决策精准度In the dynamic world of finance, asset management companies (AMCs) stand at the forefront of innovation and strategic planning. The integration of robust data analysis capabilities into their operational framework is not just a trend but a necessity to thrive in today's competitive market. Enhanced data analytics empower AMCs to dissect complex market trends, understand customer needs, and ultimately, make investment decisions with greater precision.The journey towards this enhancement begins with the aggregation of vast amounts of data. Financial markets generate an immense volume of data points daily, from stock prices and bond yields to economic indicators and corporate financial statements. By harnessing advanced data analytics tools, AMCs can process this information more efficiently, identifying patterns and insights that would otherwise remain hidden in the noise of the market.Once the data is collected, the next step is analysis. Modern data analytics employ sophisticated algorithms and machine learning techniques to forecast market movements and assess risk. These predictive models are trained on historical data, allowing them to learn from past trends and apply this knowledge to current market conditions. This level of analysis provides AMCs with a clearer picture of potential investment outcomes, enabling them to adjust their strategies accordingly.However, the power of data analytics extends beyond mere number crunching. It also encompasses the understanding of investor behavior and sentiment. Social media, news articles, and financial blogs offer a wealth of information about public perception, which can significantly influence market dynamics. By incorporating sentiment analysis into their toolkit, AMCs can gauge the mood of the market and predict how certain events or announcements might sway investor decisions.The implementation of these advanced analytical techniques leads to more informed investment decisions. Portfolio managers can identify opportunities and risks faster, allocate assets more strategically, and respond to market changes with agility. This results in portfolios that are better aligned with the investment goals and risk tolerance of clients, ensuring a higher degree of satisfaction and trust.Moreover, data analytics facilitates transparency and compliance. Regulatory bodies are increasingly demanding detailed reporting and risk management protocols. Through data analytics, AMCs can ensure that they meet these requirements, providing clear documentation of their decision-making processes and adherence to regulatory standards.In conclusion, the enhancement of data analysis capabilities is a critical step for financial asset management companies aiming to refine their investment decision-making process. By embracing the power of data, AMCs can navigate the complexities of the financial markets with confidence, delivering superior results for their clients and securing a competitive edge in the industry. The future of asset management is data-driven, and those who invest in these capabilities today will be the leaders of tomorrow. 。

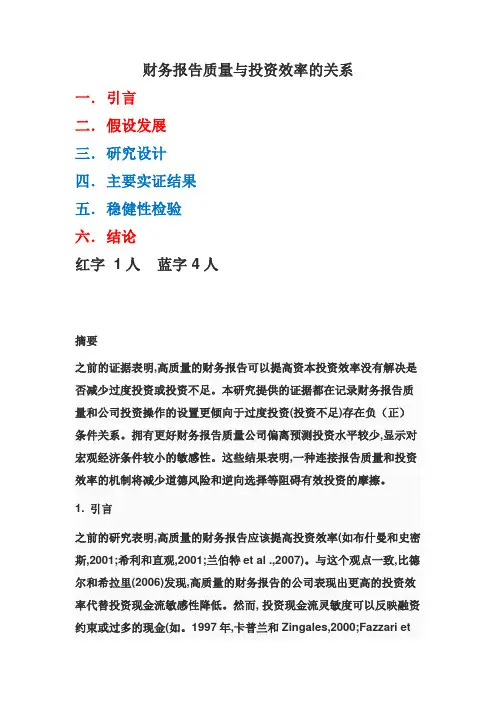

财务报告质量与投资效率的关系一.引言二.假设发展三.研究设计四.主要实证结果五.稳健性检验六.结论红字 1人蓝字 4人摘要之前的证据表明,高质量的财务报告可以提高资本投资效率没有解决是否减少过度投资或投资不足。

本研究提供的证据都在记录财务报告质量和公司投资操作的设置更倾向于过度投资(投资不足)存在负(正)条件关系。

拥有更好财务报告质量公司偏离预测投资水平较少,显示对宏观经济条件较小的敏感性。

这些结果表明,一种连接报告质量和投资效率的机制将减少道德风险和逆向选择等阻碍有效投资的摩擦。

1. 引言之前的研究表明,高质量的财务报告应该提高投资效率(如布什曼和史密斯,2001;希利和直观,2001;兰伯特et al .,2007)。

与这个观点一致,比德尔和希拉里(2006)发现,高质量的财务报告的公司表现出更高的投资效率代替投资现金流敏感性降低。

然而, 投资现金流灵敏度可以反映融资约束或过多的现金(如。

1997年,卡普兰和Zingales,2000;Fazzari etal .,2000)。

这些发现进一步提高问题,高质量的财务报告是否降低减少过度投资或投资不足。

(核心)该研究提供了证据。

脚注:本文整合了两个工作报告: 比德尔和希拉里的“财务会计质量改善投资效率如何?“和威尔第的“财务报告质量和投资效率”。

我们开始通过假定之间的联系减少财务报告质量和投资效率关系到一个企业之间的信息不对称和外部供应商的资金。

例如,更高的财务报告质量可以允许限制公司吸引资本,使其正的净现值(NPV)项目更可见投资者和证券发行减少逆向选择。

另外,提高财务报告质量控制管理激励价值的破坏活动,如帝国大厦公司充足的资本。

这可以实现,例如,如果更高的财务报告有助于写出更好的防止低效投资和/或增加投资者的监督管理投资决策的能力的合同。

基于这种推理,我们假设高质量财务报告是与较低的过度投资,降低投资不足,或两者兼而有之。

我们用三种方法来调查这些假设。

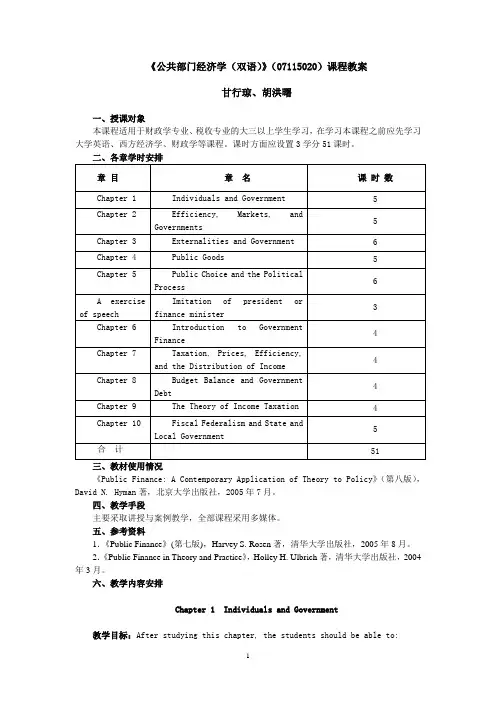

《公共部门经济学(双语)》(07115020)课程教案甘行琼、胡洪曙一、授课对象本课程适用于财政学专业、税收专业的大三以上学生学习,在学习本课程之前应先学习大学英语、西方经济学、财政学等课程。

课时方面应设置3学分51课时。

三、教材使用情况《Public Finance: A Contemporary Application of Theory to Policy》(第八版),David N. Hyman著,北京大学出版社,2005年7月。

四、教学手段主要采取讲授与案例教学,全部课程采用多媒体。

五、参考资料1.《Public Finance》(第七版),Harvey S. Rosen著,清华大学出版社,2005年8月。

2.《Public Finance in Theory and Practice》,Holley H. Ulbrich著,清华大学出版社,2004年3月。

六、教学内容安排Chapter 1 Individuals and Government教学目标:After studying this chapter, the students should be able to:1. Use a production-possibility curve to explain the trade- off between private goods and services and government goods and services.2. Describe how the provision of government goods and services through political institutions differs from market provision of goods and services and how government affects the circular flow of income and expenditure in a mixed economy.3. Discuss the various categories of federal, state, and local government expenditures in the United States and the way those expenditures are financed.内容提要:Public finance is the field of economics that studies government activities and alternative means of financing government expenditures. Modern public finance emphasizes the relationships between citizens and governments. Government goods and services are supplied through political institutions, which employ rules and procedures that have evolved in different societies for arriving at collective choices. Government goods and services are usually made available without charge for their use, and they are financed by compulsory payments (mainly taxes) levied on citizens and their activities. A major goal in the study of public finance is to analyze the economic role of government and the costs and benefits of allocating resources to government use as opposed to allowing private enterprise and households to use those resources.重点难点:The allocation of resources between government and private use; The structure of state and local government expenditure; Market failure and the functions of government: how much government is enough? Government transfer payments; Nonmarket rationing.有关提示:这一部分是公共部门经济学的引言部分,应让学生明白公共部门和私人部门的区别,以及他们各自是如何配置资源的,另外也要熟悉美国政府支出的增长情况。

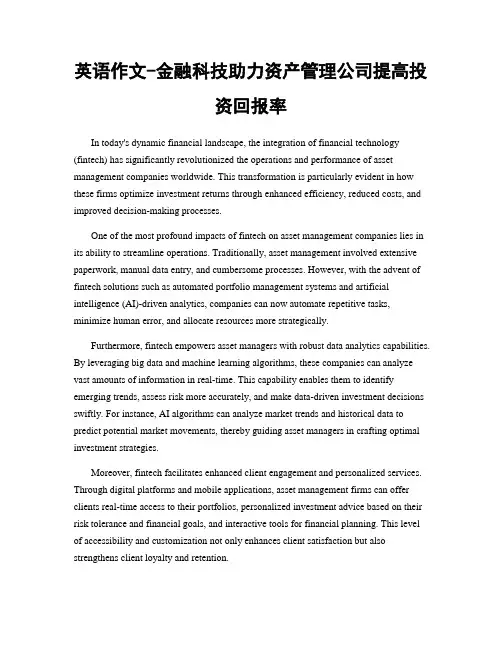

英语作文-金融科技助力资产管理公司提高投资回报率In today's dynamic financial landscape, the integration of financial technology (fintech) has significantly revolutionized the operations and performance of asset management companies worldwide. This transformation is particularly evident in how these firms optimize investment returns through enhanced efficiency, reduced costs, and improved decision-making processes.One of the most profound impacts of fintech on asset management companies lies in its ability to streamline operations. Traditionally, asset management involved extensive paperwork, manual data entry, and cumbersome processes. However, with the advent of fintech solutions such as automated portfolio management systems and artificial intelligence (AI)-driven analytics, companies can now automate repetitive tasks, minimize human error, and allocate resources more strategically.Furthermore, fintech empowers asset managers with robust data analytics capabilities. By leveraging big data and machine learning algorithms, these companies can analyze vast amounts of information in real-time. This capability enables them to identify emerging trends, assess risk more accurately, and make data-driven investment decisions swiftly. For instance, AI algorithms can analyze market trends and historical data to predict potential market movements, thereby guiding asset managers in crafting optimal investment strategies.Moreover, fintech facilitates enhanced client engagement and personalized services. Through digital platforms and mobile applications, asset management firms can offer clients real-time access to their portfolios, personalized investment advice based on their risk tolerance and financial goals, and interactive tools for financial planning. This level of accessibility and customization not only enhances client satisfaction but also strengthens client loyalty and retention.Additionally, fintech solutions contribute to cost efficiency within asset management companies. By reducing the need for manual intervention and optimizing operational processes, firms can lower administrative costs, allocate resources more efficiently, and ultimately enhance their profit margins. This cost-effectiveness enables asset managers to offer competitive fee structures to clients while maintaining profitability.Furthermore, the integration of blockchain technology has introduced new possibilities in asset management. Blockchain's decentralized and secure nature allowsfor transparent transactions, improved auditability, and reduced fraud risks. Asset management companies are exploring blockchain for applications such as smart contracts, which automate and enforce contract terms in real-time, further enhancing operational efficiency and reducing transactional friction.In conclusion, the adoption of fintech has propelled asset management companies into a new era of efficiency, agility, and client-centricity. By embracing technologies like AI, big data analytics, digital platforms, and blockchain, these firms can optimize investment returns, mitigate risks, and deliver superior services to their clients. As the fintech landscape continues to evolve, asset managers must remain proactive in adopting innovative solutions to stay competitive in an increasingly digital and interconnected global market.。

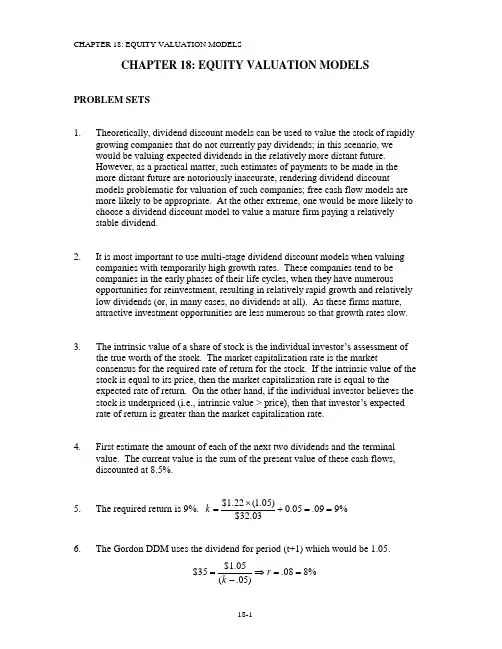

CHAPTER 18: EQUITY VALUATION MODELSPROBLEM SETS1. Theoretically, dividend discount models can be used to value the stock of rapidlygrowing companies that do not currently pay dividends; in this scenario, we would be valuing expected dividends in the relatively more distant future. However, as a practical matter, such estimates of payments to be made in the more distant future are notoriously inaccurate, rendering dividend discount models problematic for valuation of such companies; free cash flow models are more likely to be appropriate. At the other extreme, one would be more likely to choose a dividend discount model to value a mature firm paying a relatively stable dividend.2. It is most important to use multi-stage dividend discount models when valuingcompanies with temporarily high growth rates. These companies tend to be companies in the early phases of their life cycles, when they have numerous opportunities for reinvestment, resulting in relatively rapid growth and relatively low dividends (or, in many cases, no dividends at all). As these firms mature, attractive investment opportunities are less numerous so that growth rates slow.3. The intrinsic value of a share of stock is the individual investor’s assessment ofthe true worth of the stock. The market capitalization rate is the marketconsensus for the required rate of return for the stock. If the intrinsic value of the stock is equal to its price, then the market capitalization rate is equal to theexpected rate of return. On the other hand, if the individual investor believes the stock is underpriced (i.e., intrinsic value > price), then that investor’s expected rate of return is greater than the market capitalization rate.4. First estimate the amount of each of the next two dividends and the terminalvalue. The current value is the sum of the present value of these cash flows, discounted at 8.5%. 5. The required return is 9%. $1.22(1.05)0.05.099%$32.03k ⨯=+==6. The Gordon DDM uses the dividend for period (t+1) which would be 1.05.$1.05$35.088%(.05)r k =⇒==-7. The PVGO is $0.56:$3.64$41$0.560.09PVGO =-= 8. a.b.10$2$18.180.160.05D P k g ===-- The price falls in response to the more pessimistic dividend forecast. The forecast for current year earnings, however, is unchanged. Therefore, the P/E ratio falls. The lower P/E ratio is evidence of the diminished optimism concerning the firm's growth prospects.9.a.g = ROE ⨯ b = 16% ⨯ 0.5 = 8% D 1 = $2 ⨯ (1 – b) = $2 ⨯ (1 – 0.5) = $110$1$25.000.120.08D P k g ===--b. P 3 = P 0(1 + g)3 = $25(1.08)3 = $31.4910. a.b. Leading P 0/E 1 = $10.60/$3.18 = 3.33 Trailing P 0/E 0 = $10.60/$3.00 = 3.53c.275.9$16.018.3$60.10$k E P PVGO 10-=-=-= The low P/E ratios and negative PVGO are due to a poor ROE (9%) that isless than the market capitalization rate (16%).1$20.160.1212%$50D k g P g g =+=+⇒==1010[()]6% 1.25(14%6%)16%29%6%31(1)(1)$3(1.06)$1.063$1.06$10.600.160.06f m f k r E r rg D E g b D P k g β=+⨯-=+⨯-==⨯==⨯+⨯-=⨯⨯====--d.Now, you revise b to 1/3, g to 1/3 ⨯ 9% = 3%, and D 1 to:E 0 ⨯ 1.03 ⨯ (2/3) = $2.06 Thus:V 0 = $2.06/(0.16 – 0.03) = $15.85V 0 increases because the firm pays out more earnings instead of reinvesting a poor ROE. This information is not yet known to the rest of the market.11. a. 160$05.010.08$g k D P 10=-=-=b.The dividend payout ratio is 8/12 = 2/3, so the plowback ratio is b = 1/3. The implied value of ROE on future investments is found by solving:g = b ⨯ ROE with g = 5% and b = 1/3 ⇒ ROE = 15%c.Assuming ROE = k, price is equal to:120$10.012$k E P 10===Therefore, the market is paying $40 per share ($160 – $120) for growth opportunities.12. a.k = D 1/P 0 + g D 1 = 0.5 ⨯ $2 = $1g = b ⨯ ROE = 0.5 ⨯ 0.20 = 0.10Therefore: k = ($1/$10) + 0.10 = 0.20 = 20%b.Since k = ROE, the NPV of future investment opportunities is zero:010$10$kE P PVGO 10=-=-= c.Since k = ROE, the stock price would be unaffected by cutting the dividend and investing the additional earnings.13. a.k = r f + β [E(r M ) – r f ] = 8% + 1.2(15% – 8%) = 16.4% g = b ⨯ ROE = 0.6 ⨯ 20% = 12%82.101$12.0164.012.14$g k )g 1(D V 00=-⨯=-+=b. P 1 = V 1 = V 0(1 + g) = $101.82 ⨯ 1.12 = $114.04%52.181852.0100$100$04.114$48.4$P P P D )r (E 0011==-+=+=-14.Time: 01 5 6 E t $10.000 $12.000 $24.883 $27.123 D t $ 0.000 $ 0.000 $ 0.000 $10.849 b 1.00 1.00 1.00 0.60 g20.0%20.0%20.0%9.0%a.65$10.85$180.820.150.09D V k g ===⇒-- 5055$180.82$89.90(1) 1.15V V k ===+ b. The price should rise by 15% per year until year 6: because there is no dividend, the entire return must be in capital gains.c. The payout ratio would have no effect on intrinsic value because ROE = k.15. a.The solution is shown in the Excel spreadsheet below:b.,c. Using the Excel spreadsheet, we find that the intrinsic values are $29.71and $17.39, respectively.16. The solutions derived from Spreadsheet 18.2 are as follows:Intrinsic value: FCFF Intrinsic value: FCFE Intrinsic valueper share: FCFFIntrinsic value per share: FCFEa. 81,171 68,470 36.0137.83b. 59,961 49,185 24.29 27.17c. 69,81357,91329.7332.0017.Time: 0 1 2 3 D t g 25.0%25.0%25.0%5.0%a.The dividend to be paid at the end of year 3 is the first installment of adividend stream that will increase indefinitely at the constant growth rate of 5%. Therefore, we can use the constant growth model as of the end of year 2 in order to calculate intrinsic value by adding the present value of the first two dividends plus the present value of the price of the stock at the end of year 2. The expected price 2 years from now is:P 2 = D 3/(k – g) = $1.953125/(0.20 – 0.05) = $13.02 The PV of this expected price is: $13.02/1.202 = $9.04 The PV of expected dividends in years 1 and 2 is:13.2$20.15625.1$20.125.1$2=+ Thus the current price should be: $9.04 + $2.13 = $11.17b. Expected dividend yield = D 1/P 0 = $1.25/$11.17 = 0.112 = 11.2%c.The expected price one year from now is the PV at that time of P 2 and D 2:P 1 = (D 2 + P 2)/1.20 = ($1.5625 + $13.02)/1.20 = $12.15 The implied capital gain is:(P 1 – P 0)/P 0 = ($12.15 – $11.17)/$11.17 = 0.088 = 8.8%The sum of the implied capital gains yield and the expected dividend yield is equal to the market capitalization rate. This is consistent with the DDM.Time: 0 1 4 5 E t $5.000 $6.000 $10.368 $10.368 D t$0.000$0.000$0.000$10.368Dividends = 0 for the next four years, so b = 1.0 (100% plowback ratio). a.54$10.368$69.120.15D P k === (Since k=ROE, knowing the plowback rate is unnecessary)4044$69.12$39.52(1) 1.15P V k ===+b.Price should increase at a rate of 15% over the next year, so that the HPR will equal k.19. Before-tax cash flow from operations$2,100,000 Depreciation 210,000 Taxable Income 1,890,000 Taxes (@ 35%)661,500 After-tax unleveraged income1,228,500 After-tax cash flow from operations(After-tax unleveraged income + depreciation) 1,438,500 New investment (20% of cash flow from operations) 420,000 Free cash flow(After-tax cash flow from operations – new investment)$1,018,500The value of the firm (i.e., debt plus equity) is:000,550,14$05.012.0500,018,1$10=-=-=g k C V Since the value of the debt is $4 million, the value of the equity is $10,550,000.20. a.g = ROE ⨯ b = 20% ⨯ 0.5 = 10%11$10.015.010.150.0$g k )g 1(D g k D P 010=-⨯=-+=-=b. Time EPS Dividend Comment 0 $1.0000 $0.50001 $1.1000 $0.5500 g = 10%, plowback = 0.502 $1.2100 $0.7260EPS has grown by 10% based on last year’s earnings plowback and ROE; this year’s earnings plowback ratio now falls to 0.40 and payout ratio = 0.603 $1.2826$0.7696 EPS grows by (0.4) (15%) = 6% andpayout ratio = 0.60At time 2: 551.8$06.015.07696.0$g k D P 32=-=-= At time 0: 493.7$)15.1(551.8$726.0$15.155.0$V 20=++=c.P 0 = $11 and P 1 = P 0(1 + g) = $12.10(Because the market is unaware of the changed competitive situation, itbelieves the stock price should grow at 10% per year.)P 2 = $8.551 after the market becomes aware of the changed competitive situation.P 3 = $8.551 ⨯ 1.06 = $9.064 (The new growth rate is 6%.) Year Return1 %0.15150.011$55.0$)11$10.12($==+-2 %3.23233.010.12$726.0$)10.12$551.8($-=-=+-3%0.15150.0551.8$7696.0$)551.8$064.9($==+-Moral: In "normal periods" when there is no special information, the stock return = k = 15%. When special information arrives, all the abnormal return accrues in that period , as one would expect in an efficient market.CFA PROBLEMS1. a. This director is confused. In the context of the constant growth model[i.e., P 0 = D 1/(k – g)], it is true that price is higher when dividends are higher holding everything else including dividend growth constant . But everything else will not be constant. If the firm increases the dividend payout rate, the growth rate g will fall, and stock price will not necessarily rise. In fact, if ROE > k , price will fall.b. (i) An increase in dividend payout will reduce the sustainable growth rateas less funds are reinvested in the firm. The sustainable growth rate (i.e. ROE ⨯ plowback) will fall as plowback ratio falls.(ii) The increased dividend payout rate will reduce the growth rate of book value for the same reason -- less funds are reinvested in the firm.2.Using a two-stage dividend discount model, the current value of a share of Sundanci is calculated as follows.2322110)k 1()g k (D )k 1(D )k 1(D V +-++++= 98.43$14.1)13.014.0(5623.0$14.14976.0$14.13770.0$221=-++= where: E 0 = $0.952 D 0 = $0.286E 1 = E 0 (1.32)1 = $0.952 ⨯ 1.32 = $1.2566 D 1 = E 1 ⨯ 0.30 = $1.2566 ⨯ 0.30 = $0.3770 E 2 = E 0 (1.32)2 = $0.952 ⨯ (1.32)2 = $1.6588 D 2 = E 2 ⨯ 0.30 = $1.6588 ⨯ 0.30 = $0.4976E 3 = E 0 ⨯ (1.32)2 ⨯ 1.13 = $0.952 ⨯ (1.32)3 ⨯ 1.13 = $1.8744 D 3 = E 3 ⨯ 0.30 = $1.8743 ⨯ 0.30 = $0.56233. a. Free cash flow to equity (FCFE) is defined as the cash flow remaining aftermeeting all financial obligations (including debt payment) and aftercovering capital expenditure and working capital needs. The FCFE is ameasure of how much the firm can afford to pay out as dividends, but in agiven year may be more or less than the amount actually paid out.Sundanci's FCFE for the year 2008 is computed as follows: FCFE = Earnings + Depreciation - Capital expenditures - Increase in NWC= $80 million + $23 million - $38 million - $41 million = $24 millionFCFE per share =$24 million$0.286 # of shares outstanding84 million sharesFCFE==At this payout ratio, Sundanci's FCFE per share equals dividends per share.b. The FCFE model requires forecasts of FCFE for the high growth years(2009 and 2010) plus a forecast for the first year of stable growth (2011) inorder to allow for an estimate of the terminal value in 2010 based onperpetual growth. Because all of the components of FCFE are expected togrow at the same rate, the values can be obtained by projecting the FCFE atthe common rate. (Alternatively, the components of FCFE can be projectedand aggregated for each year.)This table shows the process for estimating the current per share value: FCFE Base AssumptionsShares outstanding: 84 million, k = 14%Actual 2008 Projected2009Projected2010Projected2011Growth rate (g) 27% 27% 13%Total Per shareEarnings after tax $80 $0.952 $1.2090 $1.5355 $1.7351 Plus: Depreciation expense $23 $0.274 $0.3480 $0.4419 $0.4994 Less: Capital expenditures $38 $0.452 $0.5740 $0.7290 $0.8238 Less: Increase in net working capital $41 $0.488 $0.6198 $0.7871 $0.8894 Equals: FCFE $24 $0.286 $0.3632 $0.4613 $0.5213 Terminal value $52.1300*Total cash flows to equity $0.3632 $52.5913** Discounted value $0.3186*** $40.4673*** Current value per share $40.7859*****Projected 2010 Terminal value = (Projected 2011 FCFE)/(r - g)**Projected 2010 Total cash flows to equity =Projected 2010 FCFE + Projected 2010 Terminal value***Discounted values obtained usingk= 14%****Current value per share=Sum of Discounted Projected 2009 and 2010 Total FCFEc. i. The DDM uses a strict definition of cash flows to equity, i.e. the expecteddividends on the common stock. In fact, taken to its extreme, the DDM cannotbe used to estimate the value of a stock that pays no dividends. The FCFEmodel expands the definition of cash flows to include the balance of residualcash flows after all financial obligations and investment needs have been met.Thus the FCFE model explicitly recognizes the firm’s investment and financingpolicies as well as its dividend policy. In instances of a change of corporatecontrol, and therefore the possibility of changing dividend policy, the FCFEmodel provides a better estimate of value. The DDM is biased toward findinglow P/E ratio stocks with high dividend yields to be undervalued and conversely,high P/E ratio stocks with low dividend yields to be overvalued. It is considereda conservative model in that it tends to identify fewer undervalued firms asmarket prices rise relative to fundamentals. The DDM does not allow for thepotential tax disadvantage of high dividends relative to the capital gainsachievable from retention of earnings.ii. Both two-stage valuation models allow for two distinct phases of growth, aninitial finite period where the growth rate is abnormal, followed by a stablegrowth period that is expected to last indefinitely. These two-stage modelsshare the same limitations with respect to the growth assumptions. First, thereis the difficulty of defining the duration of the extraordinary growth period. Forexample, a longer period of high growth will lead to a higher valuation, andthere is the temptation to assume an unrealistically long period of extraordinarygrowth. Second, the assumption of a sudden shift from high growth to lower,stable growth is unrealistic. The transformation is more likely to occurgradually, over a period of time. Given that the assumed total horizon does notshift (i.e., is infinite), the timing of the shift from high to stable growth is acritical determinant of the valuation estimate. Third, because the value is quitesensitive to the steady-state growth assumption, over- or under-estimating thisrate can lead to large errors in value. The two models share other limitations aswell, notably difficulties in accurately forecasting required rates of return, indealing with the distortions that result from substantial and/or volatile debtratios, and in accurately valuing assets that do not generate any cash flows.4. a. The formula for calculating a price earnings ratio (P/E) for a stable growthfirm is the dividend payout ratio divided by the difference between therequired rate of return and the growth rate of dividends. If the P/E iscalculated based on trailing earnings (year 0), the payout ratio is increasedby the growth rate. If the P/E is calculated based on next year’s earnings(year 1), the numerator is the payout ratio.P/E on trailing earnings:P/E = [payout ratio ⨯ (1 + g)]/(k - g) = [0.30 ⨯ 1.13]/(0.14 - 0.13) = 33.9P/E on next year's earnings:P/E = payout ratio/(k - g) = 0.30/(0.14 - 0.13) = 30.0b.The P/E ratio is a decreasing function of riskiness; as risk increases, the P/E ratio decreases. Increases in the riskiness of Sundanci stock would be expected to lower the P/E ratio. The P/E ratio is an increasing function of the growth rate of the firm; the higher the expected growth, the higher the P/E ratio. Sundanci would command a higher P/E if analysts increase the expected growth rate. The P/E ratio is a decreasing function of the market risk premium. An increased market risk premium increases the required rate of return, lowering the price of a stock relative to its earnings. A higher market risk premium would be expected to lower Sundanci's P/E ratio.5. a.The sustainable growth rate is equal to: plowback ratio × return on equity = b × ROE Net Income - (Dividends per share shares outstanding)where Net Income b ⨯= ROE = Net Income/Beginning of year equity In 2007: b = [208 – (0.80 × 100)]/208 = 0.6154 ROE = 208/1380 = 0.1507 Sustainable growth rate = 0.6154 × 0.1507 = 9.3% In 2010: b = [275 – (0.80 × 100)]/275 = 0.7091 ROE = 275/1836 = 0.1498 Sustainable growth rate = 0.7091 × 0.1498 = 10.6%b.i. The increased retention ratio increased the sustainable growth rate. Retention ratio = [Net Income - (Dividend per share Shares Oustanding)]Net Income ⨯ Retention ratio increased from 0.6154 in 2007 to 0.7091 in 2010. This increase in the retention ratio directly increased the sustainable growth rate because the retention ratio is one of the two factors determining the sustainable growth rate. ii. The decrease in leverage reduced the sustainable growth rate. Financial leverage = (Total Assets/Beginning of year equity) Financial leverage decreased from 2.34 (= 3230/1380) at the beginning of 2007 to 2.10 at the beginning of 2010 (= 3856/1836) This decrease in leverage directly decreased ROE (and thus the sustainable growth rate) because financial leverage is one of the factors determining ROE (and ROE is one of the two factors determining the sustainable growth rate).6. a. The formula for the Gordon model is:00(1)D g V k g ⨯+=- where: D 0 = dividend paid at time of valuation g = annual growth rate of dividends k = required rate of return for equity In the above formula, P 0, the market price of the common stock, substitutes for V 0 and g becomes the dividend growth rate implied by the market: P 0 = [D 0 × (1 + g)]/(k – g) Substituting, we have: 58.49 = [0.80 × (1 + g)]/(0.08 – g) ⇒ g = 6.54%b.Use of the Gordon growth model would be inappropriate to value Dynamic’s common stock, for the following reasons: i. The Gordon growth model assumes a set of relationships about the growth rate for dividends, earnings, and stock values. Specifically, the model assumes that dividends, earnings, and stock values will grow at the same constant rate. In valuing Dynamic’s common stock, the Gordon growth model is inapp ropriate because management’s dividend policy has held dividends constant in dollar amount although earnings have grown, thus reducing the payout ratio. This policy is inconsistent with the Gordon model assumption that the payout ratio is constant. ii. It could also be argued that use of the Gordon model, given Dynamic’s current dividend policy, violates one of the general conditions for suitability of the model, namely that the company’s dividend policy bears an understandable and consistent relationship with the company’s profitability.7. a.The industry’s estimated P/E can be computed using the following model: 01Payout Ratio P E k g =- However, sincekand g are not explicitly given, they must be computed using the following formulas: g ind = ROE ⨯ retention rate = 0.25 ⨯ 0.40 = 0.10 k ind = government bond yield + ( industry beta ⨯ equity risk premium) = 0.06 + (1.2 ⨯ 0.05) = 0.12 Therefore: 010.6030.00.120.10P E ==-b. i. Forecast growth in real GDP would cause P/E ratios to be generallyhigher for Country A. Higher expected growth in GDP implies higher earnings growth and a higher P/E. ii. Government bond yield would cause P/E ratios to be generally higher for Country B. A lower government bond yield implies a lower risk-free rate and therefore a higher P/E. iii. Equity risk premium would cause P/E ratios to be generally higher for Country B. A lower equity risk premium implies a lower required return and a higher P/E.8. a.k = r f + β (k M – r f ) = 4.5% + 1.15(14.5% - 4.5%) = 16%b.Year Dividend2009 $1.722010 $1.72 ⨯ 1.12 = $1.932011 $1.72 ⨯ 1.122 = $2.162012 $1.72 ⨯ 1.123 = $2.422013 $1.72 ⨯ 1.123 ⨯ 1.09 = $2.63 Present value of dividends paid in 2010 – 2012:Year PV of Dividend2010 $1.93/1.161 = $1.662011 $2.16/1.162 = $1.612012 $2.42/1.163 = $1.55Total = $4.82 Price at year-end 201257.37$09.016.063.2$2013=-=-=g k D PV in 2009 of this stock price 07.24$16.157.37$3== Intrinsic value of stock = $4.82 + $24.07 = $28.89c. The data in the problem indicate that Quick Brush is selling at a pricesubstantially below its intrinsic value, while the calculations abovedemonstrate that SmileWhite is selling at a price somewhat above theestimate of its intrinsic value. Based on this analysis, Quick Brush offersthe potential for considerable abnormal returns, while SmileWhite offersslightly below-market risk-adjusted returns.d. Strengths of two-stage versus constant growth DDM:∙ Two-stage model allows for separate valuation of two distinct periods ina company’s future. This can accommodate life cycle effects. It also canavoid the difficulties posed by initial growth that is higher than thediscount rate.∙ Two-stage model allows for initial period of above-sustainable growth. Itallows the analyst to make use of her expectations regarding when growthmight shift from off-trend to a more sustainable level.A weakness of all DDMs is that they are very sensitive to input values.Small changes in k or g can imply large changes in estimated intrinsic value.These inputs are difficult to measure.9. a. The value of a share of Rio National equity using the Gordon growth modeland the capital asset pricing model is $22.40, as shown below.Calculate the required rate of return using the capital asset pricing model:k = r f + β × (k M – r f ) = 4% + 1.8 × (9% – 4%) = 13% Calculate the share value using the Gordon growth model:40.22$12.013.0)12.01(20.0$g k g)(1D P o 0=-+⨯=-+⨯=b. The sustainable growth rate of Rio National is 9.97%, calculated as follows: g = b × ROE = Earnings Retention Rate × ROE = (1 – Payout Ratio) × ROE =%97.90997.035.270$16.30$16.30$20.3$1Equity BeginningIncome Net Income Net ividends D 1==⨯⎪⎭⎫ ⎝⎛-=⨯⎪⎭⎫ ⎝⎛-10. a. To obtain free cash flow to equity (FCFE), the two adjustments that Shaarshould make to cash flow from operations (CFO) are:1. Subtract investment in fixed capital: CFO does not take into account theinvesting activities in long-term assets, particularly plant and equipment.The cash flows corresponding to those necessary expenditures are notavailable to equity holders and therefore should be subtracted from CFOto obtain FCFE.2. Add net borrowing: CFO does not take into account the amount ofcapital supplied to the firm by lenders (e.g., bondholders). The newborrowings, net of debt repayment, are cash flows available to equityholders and should be added to CFO to obtain FCFE.b. Note 1: Rio National had $75 million in capital expenditures during the year.Adjustment: negative $75 millionThe cash flows required for those capital expenditures (–$75 million) areno longer available to the equity holders and should be subtracted from netincome to obtain FCFE.Note 2: A piece of equipment that was originally purchased for $10 million was sold for $7 million at year-end, when it had a net book value of $3million. Equipment sales are unusual for Rio National.Adjustment: positive $3 millionIn calculating FCFE, only cash flow investments in fixed capital should beconsidered. The $7 million sale price of equipment is a cash inflow nowavailable to equity holders and should be added to net income. However, the gain over book value that was realized when selling the equipment ($4million) is already included in net income. Because the total sale is cash, not just the gain, the $3 million net book value must be added to net income.Therefore, the adjustment calculation is:$7 million in cash received – $4 million of gain recorded in net income =$3 million additional cash received added to net income to obtain FCFE.Note 3: The decrease in long-term debt represents an unscheduled principal repayment; there was no new borrowing during the year.Adjustment: negative $5 millionThe unscheduled debt repayment cash flow (–$5 million) is an amount nolonger available to equity holders and should be subtracted from net income to determine FCFE.Note 4: On January 1, 2008, the company received cash from issuing400,000 shares of common equity at a price of $25.00 per share.No adjustmentTransactions between the firm and its shareholders do not affect FCFE.To calculate FCFE, therefore, no adjustment to net income is requiredwith respect to the issuance of new shares.Note 5: A new appraisal during the year increased the estimated marketvalue of land held for investment by $2 million, which was not recognizedin 2008 income.No adjustmentThe increased market value of the land did not generate any cash flow andwas not reflected in net income. To calculate FCFE, therefore, no adjustment to net income is required.c. Free cash flow to equity (FCFE) is calculated as follows:FCFE = NI + NCC – FCINV – WCINV + Net Borrowingwhere NCC = non-cash chargesFCINV = investment in fixed capitalWCINV = investment in working capital*Supplemental Note 2 in Table 18H affects both NCC and FCINV.11. Rio National’s equity is relatively undervalued compared to the industry on a P/E-to-growth (PEG) basi s. Rio National’s PEG ratio of 1.33 is below the industry PEG ratio of 1.66. The lower PEG ratio is attractive because it implies that the growth rate at Rio National is available at a relatively lower price than is the case for theindustry. The PEG ratios for Rio National and the industry are calculated below: Rio NationalCurrent Price = $25.00Normalized Earnings per Share = $1.71Price-to-Earnings Ratio = $25/$1.71 = 14.62Growth Rate (as a percentage) = 11PEG Ratio = 14.62/11 = 1.33IndustryPrice-to-Earnings Ratio = 19.90Growth Rate (as a percentage) = 12PEG Ratio = 19.90/12 = 1.66。

英语作文-金融科技助力资产管理公司降低运营成本,提高盈利能力In the realm of asset management, the integration of financial technology (fintech) has emerged as a transformative force, enabling companies to streamline operations, reduce costs, and enhance profitability. Fintech solutions encompass a broad spectrum of technologies, from advanced analytics to artificial intelligence, each tailored to meet the unique demands of asset management firms seeking to stay competitive in a rapidly evolving market landscape.One of the most significant challenges faced by asset management companies is the efficient allocation of resources across various functions such as portfolio management, compliance, and client servicing. Traditionally, these processes have been labor-intensive and prone to human error. However, with the advent of fintech, firms can now automate routine tasks, thereby freeing up valuable human capital to focus on higher-value activities. For instance, algorithms powered by machine learning algorithms can analyze vast amounts of data in real-time, identifying market trends and investment opportunities that would have otherwise been overlooked.Moreover, fintech plays a crucial role in risk management by providing sophisticated modeling tools that assess portfolio risk exposure under different scenarios. This proactive approach allows asset managers to mitigate risks effectively and protect client investments. By leveraging these technologies, firms not only enhance their risk-adjusted returns but also bolster investor confidence in their ability to navigate volatile market conditions.Cost reduction is another compelling advantage of integrating fintech into asset management operations. Traditional methods often incur significant overhead costs associated with manual data entry, reconciliation, and reporting. In contrast, fintech solutions automate these processes, resulting in operational efficiencies and substantial cost savings over time. Furthermore, cloud computing infrastructure enables seamlessscalability, allowing firms to adapt swiftly to changing market dynamics without the burden of heavy upfront investments in IT infrastructure.Client engagement and retention are critical metrics for asset managers seeking sustained growth. Fintech empowers firms to deliver personalized client experiences through digital platforms and mobile applications. These technologies enable investors to access real-time performance updates, portfolio analytics, and customized investment recommendations at their convenience. Such transparency and accessibility foster stronger client relationships based on trust and responsiveness, ultimately driving client retention and organic growth.Additionally, regulatory compliance remains a cornerstone of asset management practices, with stringent requirements necessitating robust monitoring and reporting capabilities. Fintech solutions offer compliance automation tools that ensure adherence to regulatory standards while minimizing the administrative burden on compliance teams. This proactive compliance approach not only reduces the risk of penalties but also enhances operational efficiency by streamlining reporting processes and ensuring timely submissions.In conclusion, the integration of fintech in asset management represents a paradigm shift towards efficiency, profitability, and client-centricity. By harnessing the power of advanced technologies, firms can optimize operations, reduce costs, manage risks effectively, and deliver superior client experiences. As the fintech ecosystem continues to evolve, asset managers must embrace innovation to stay ahead of the curve and capitalize on emerging opportunities in the global financial markets. By doing so, they can position themselves as industry leaders committed to driving sustainable growth and value creation for their clients and stakeholders alike.。

Open Journal of Legal Science 法学, 2023, 11(4), 3246-3254 Published Online July 2023 in Hans. https:///journal/ojls https:///10.12677/ojls.2023.114463金融机构投资者适当性义务的规范逻辑——以联储证券公司系列案为例辨析证券法第八十八条宁高文上海大学法学院,上海收稿日期:2023年5月9日;录用日期:2023年5月23日;发布日期:2023年7月31日摘要 投资者适当性义务要求金融机构在了解产品、客户的基础上,向适当的投资者推介、销售适当的金融产品,以便投资者能够在充分了解金融产品性质及风险的基础上做出自主决定。

我国逐步建立起了投资者适当性义务制度,《证券法》第八十八条的规定使该制度第一次体现在立法中。

我国可以美国的信义义务为延伸,将诚实信用原则作为理论基础;义务的履行要区别分类、确定分类标准及参数、法院要实质审查避免形式化,关注“质”与“量”,区分合格投资者制度、告知说明义务与信息披露义务;发行人与销售者承担连带侵权责任具有合理性;完善逾级销售、责任减免情形,构建规范补充体系。

关键词投资者适当性义务,诚实信用原则,告知说明,侵权责任,规则体系The Regulatory Logic of Investor Suitability Obligations for Financial Institutions—Discussing Article 88 of the Securities Law with the Example of the Federal Reserve Securities Corporation SeriesGaowen NingSchool of Law, Shanghai University, Shanghai Received: May 9th , 2023; accepted: May 23rd , 2023; published: Jul. 31st , 2023AbstractThe investor suitability obligation requires financial institutions to recommend and sell appro-priate financial products to appropriate investors on the basis of knowledge of the products and宁高文customers, so that investors can make their own decisions based on a full understanding of the nature and risks of the financial products. A system of investor suitability obligations has gradu-ally been established in China, with the provisions of Article 88 of the Securities Law giving the system its first expression in legislation. China can take the US fiduciary duty as an extension, tak-ing the principle of honesty and credit as the theoretical basis; the performance of the duty should be classified differently; the criteria and parameters of the classification should be determined; the court should review the substance and avoid formalisation, pay attention to the “quality” and “quantity”, distinguish the qualified investor system, the obligation to inform and explain and the obligation to disclose information; it is reasonable for the issuer and the seller to bear joint and several liability for infringement; improve the situation of over-level sales and liability relief, and build a supplementary system of regulation.KeywordsInvestor Suitability Obligations, Good Faith Principles, Disclosure, Tort Liability, Rule SystemThis work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0)./licenses/by/4.0/1. 引言金融机构投资者适当性义务近年来在《证券法》领域备受关注,在2023年北京金融法院发布的十大案件的第一案件就是有关适当性义务的落实,不仅十多年前的金融危机涉及到适当性义务,而且随着现代金融工具的发展、市场大环境低迷、科学技术的进步等等都要求金融机构在与投资者进行交易时要审慎,而且,由于投资者同金融机构相比在信息、知识、经济能力、地位等方面都存在不对称,强制信息披露与传统监管机制不完全有效,因此开辟了第三条与投资者在缔约、履约、持续服务中的投资者保护路径。

提高做生意效果的商务英语精选当你在主持会议时,及时的集中大家的注意力是至关重要的。

最好的开始会议的方式就是给出直接的陈述。

"The purpose ofthis meeting is to decide on the pany logo."防止类似以下的间接的陈述,"Well, here's the agenda,"或是"Maybe we should get started."那你会马上失去别人的注意力你的老板把每个人叫就办公室商谈一个问题同时也询问了你的意见,商务英语《用以下商务英语做生意效果果然非凡》。

将你的回复以"I remend ..."或是"In my opinion ...."开始。

此外,要用权威性的语气答复,使用 "should" 而不用"could"使语气更强。

"In my opinion, we should consider different vendors" 比"Maybe we could think about different vendors."语气更强。

如果你想让语气听起来以上的句子更重的话,那就用"I'm positive that ?或是"I really feel that ?来开始,说,"I'm positive that it's the vendor's fault"想听者表示出你对此是非常的肯定。

就是说,“我很肯定,那你也应该肯定!”没那么自信的人会说,A"John in Marketing said it could be thevendor's fault. I thought he had a good point."商务讨论有时会跑题。

怎么提高金融实力英文作文How to Improve Financial Strength。

Financial strength is an important factor for individuals and businesses to achieve their goals. It is the ability to manage finances effectively, make wise investment decisions, and maintain a stable financial position. Improving financial strength requires discipline, knowledge, and a willingness to take risks. In this essay, I will discuss ways to improve financial strength.Firstly, it is important to develop a budget and stick to it. A budget helps to prioritize spending and avoid overspending. It is important to track expenses and adjust the budget accordingly. This requires discipline and commitment to the budgeting process. By sticking to a budget, individuals and businesses can save money andinvest in opportunities that will improve their financial position.Secondly, it is important to invest wisely. Investing in stocks, bonds, and real estate can provide a high return on investment. However, it is important to research and understand the risks involved in each investment. Diversifying investments can also reduce risk and improve financial stability. It is important to seek the advice of a financial advisor to make informed investment decisions.Thirdly, it is important to reduce debt and improve credit scores. High levels of debt can limit financial opportunities and increase financial stress. It is important to pay off debt as quickly as possible and avoid taking on new debt. Improving credit scores can also improve financial opportunities and reduce interest rates on loans and credit cards.Lastly, it is important to stay informed aboutfinancial trends and opportunities. Reading financial news, attending seminars, and networking with other professionals can provide valuable insights into the financial industry. This knowledge can help individuals and businesses make informed decisions and take advantage of financialopportunities.In conclusion, improving financial strength requires discipline, knowledge, and a willingness to take risks. Developing a budget, investing wisely, reducing debt, improving credit scores, and staying informed about financial trends are important steps to improve financial strength. By taking these steps, individuals and businesses can achieve their financial goals and maintain a stable financial position.。

如何使公司提高利润的英语作文English:To increase company profits, several strategies can be implemented. Firstly, optimizing operational efficiency is crucial. This involves streamlining processes, reducing waste, and improving productivity through better resource allocation and automation where possible. Secondly, focusing on innovation and product development can open up new revenue streams and differentiate the company from competitors. This could involve investing in research and development to create unique products or services that meet market demands. Thirdly, effective marketing and sales strategies are essential. Utilizing digital marketing techniques, targeting the right audience, and establishing strong customer relationships can lead to increased sales and market share. Additionally, cost management plays a significant role. Negotiating better deals with suppliers, managing overhead costs, and implementing cost-saving measures can directly impact the bottom line. Lastly, investing in employee training and development can enhance workforce skills and motivation, leading to improved performance and customer satisfaction, ultimately driving higher profits.中文翻译:要增加公司利润,可以实施几种策略。

如何提升加分效率英语作文To enhance the efficiency of scoring in English compositions, several strategies can be employed. Here are some effective methods:1. Clear Structure and Organization: Ensure that your essay has a clear introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. Each paragraph should focus on one main idea and transition smoothly to the next. This structure helps the reader follow your argument easily, which can lead to higher scores.2. Use Varied Vocabulary and Sentence Structures: Demonstrating a wide range of vocabulary and sentence structures showcases your language proficiency. Avoid repetition and strive for diversity in your word choice and sentence construction. This not only makes your essay more engaging but also demonstrates your command of the English language.3. Support Ideas with Evidence and Examples: Back up your arguments with relevant evidence and examples. This could include facts, statistics, anecdotes, or quotations. Providing evidence strengthens your argument and shows that you have a deep understanding of the topic.4. Address the Prompt Directly: Make sure your essay directly addresses the prompt given. Understand what is being asked of you and tailor your response accordingly. Failure to address the prompt appropriately can result in lower scores, so take the time to analyze the prompt carefully before crafting your essay.5. Proofread and Edit: Take the time to proofread your essay for grammatical errors, punctuation mistakes, and typos. Editing ensures that your writing is clear, concise, and free of errors, which can positively impact your score. Consider seeking feedback from peers or teachers toidentify areas for improvement.6. Practice Time Management: Practice writing essays within a set time limit to improve your time managementskills. Allocate time for planning, writing, and revising your essay to ensure that you can complete it within the given timeframe. Practicing under timed conditions can help you become more efficient and confident in your writing abilities.7. Read Sample Essays and Analyze Scoring Rubrics: Study sample essays and scoring rubrics to understand what makes a high-scoring essay. Pay attention to the structure, language use, and content of successful essays, and usethis knowledge to inform your own writing. Analyzing scoring rubrics can also help you understand how your essays are evaluated and what criteria you need to meet to achieve a higher score.By incorporating these strategies into your writing process, you can improve the efficiency and effectiveness of your English compositions and ultimately boost your scores. Remember to practice regularly and seek feedback to continue refining your writing skills.。

怎样提高理财意识的英语作文Financial awareness is a crucial aspect of personal and professional life. It encompasses the understanding and management of one's financial resources, including income, expenses, savings, and investments. Developing a strong financial awareness can lead to greater financial stability, the ability to achieve long-term goals, and a sense of control over one's financial future. In this essay, we will explore various strategies and techniques that can help individuals improve their financial awareness.The first step in improving financial awareness is to establish a comprehensive understanding of one's current financial situation. This involves carefully tracking income and expenses, categorizing spending, and identifying areas where savings can be made. By creating a detailed budget, individuals can gain a clear picture of their financial landscape, allowing them to make informed decisions about their spending and saving habits.One effective way to enhance financial awareness is to regularly review and analyze one's financial statements, such as bankstatements, credit card statements, and investment statements. This practice can help individuals identify patterns in their spending, detect any unauthorized or unexpected charges, and monitor the performance of their investments. By staying up-to-date with their financial records, individuals can make more informed decisions and identify opportunities for improvement.Another important aspect of financial awareness is understanding the concept of compound interest and its impact on savings and investments. Compound interest is the interest earned on interest, and it can have a significant effect on the growth of one's financial assets over time. By understanding the power of compound interest, individuals can make more informed decisions about their savings and investment strategies, ultimately leading to a stronger financial future.In addition to understanding the mechanics of personal finance, it is crucial to develop a comprehensive understanding of financial products and services. This includes knowledge of different types of bank accounts, credit cards, loans, insurance policies, and investment options. By educating themselves on the features, benefits, and potential risks associated with these financial tools, individuals can make more informed decisions about which products and services best suit their needs and financial goals.Improving financial awareness also involves developing a solid understanding of personal financial management principles, such as the importance of saving, the impact of debt, and the role of credit in one's financial well-being. By learning about these fundamental concepts, individuals can make more informed decisions about their spending, borrowing, and saving habits, ultimately leading to greater financial stability and security.One effective way to enhance financial awareness is to seek out educational resources and financial literacy programs. These can come in the form of workshops, seminars, online courses, or even one-on-one consultations with financial advisors. By actively engaging in these learning opportunities, individuals can expand their knowledge, gain new skills, and develop a deeper understanding of personal finance.Additionally, staying informed about current economic trends, financial regulations, and market conditions can also contribute to improved financial awareness. By following reputable news sources, financial blogs, and industry publications, individuals can stay up-to-date on the latest developments and make more informed decisions about their financial strategies.Finally, it is important to recognize that improving financial awareness is an ongoing process that requires a commitment tocontinuous learning and self-reflection. As individual circumstances and financial needs evolve over time, it is crucial to regularly review and adjust one's financial strategies to ensure they remain aligned with one's goals and priorities.In conclusion, developing a strong financial awareness is essential for achieving financial stability, security, and long-term success. By implementing the strategies and techniques outlined in this essay, individuals can take control of their financial futures, make informed decisions, and ultimately improve their overall financial well-being.。

英语作文-金融科技助力资产管理公司提升投资者体验In the rapidly evolving landscape of asset management, financial technology, commonly known as fintech, has emerged as a transformative force. By harnessing the power of cutting-edge technologies, asset management companies are revolutionizing the investor experience, offering unprecedented levels of efficiency, transparency, and personalization.The integration of fintech solutions into asset management practices is not just a trend; it's a strategic imperative. With the advent of big data analytics, artificial intelligence, and blockchain technology, asset managers can now provide investors with real-time insights, predictive analytics, and more secure transactions.Big Data Analytics has enabled firms to process vast amounts of information to identify investment opportunities and risks that were previously undetectable. Investors benefit from this through more informed decision-making and tailored investment strategies that align with their individual goals and risk profiles.Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been instrumental in automating complex processes, from portfolio management to customer service. AI-driven chatbots and virtual assistants provide investors with instant responses to their queries, while algorithmic trading systems execute trades at optimal prices, enhancing returns.Blockchain Technology is redefining the notion of trust in financial transactions. By creating immutable records of all transactions, blockchain ensures transparency and security, reducing the likelihood of fraud and errors. This fosters a sense of confidence among investors, knowing their assets are managed with integrity.Moreover, Robo-Advisors represent a significant leap forward in democratizing investment advice. These automated platforms offer personalized advice at a fraction ofthe cost of traditional financial advisors, making wealth management services accessible to a broader audience.The user interface and experience (UI/UX) design of fintech applications also play a crucial role. A user-friendly platform that provides a seamless experience across various devices is critical for engaging the modern investor who expects to manage their investments on the go.Asset management companies that embrace fintech are also better positioned to comply with regulatory requirements. Regulatory technology, or regtech, helps firms navigate the complex landscape of financial regulations, ensuring compliance while minimizing costs.In conclusion, fintech is not merely an adjunct to traditional asset management practices; it is a catalyst for innovation and improvement. As asset management firms continue to integrate fintech solutions, investors stand to gain from enhanced experiences that are secure, efficient, and tailored to their needs. The future of asset management lies in the synergy between financial expertise and technological innovation, where every investor can feel empowered and well-served. 。

提高收益的英文作文英文:To increase my income, there are several strategiesthat I have used and found effective. Firstly, I have invested in the stock market. By doing thorough research and analyzing market trends, I have been able to make profitable investments. This has provided me with a steady stream of passive income.Secondly, I have started a side hustle. I am passionate about photography, so I have started offering my services as a photographer for events and weddings. This has not only provided me with extra income, but also allowed me to pursue my hobby.Lastly, I have taken advantage of cashback and rewards programs. By using credit cards that offer cashback or rewards for purchases, I have been able to save money and earn rewards that can be redeemed for cash or otherbenefits.Overall, these strategies have helped me increase my income and achieve my financial goals. It is important to note that these strategies require effort and dedication, but the rewards are worth it.中文:为了提高我的收入,我采用了几种有效的策略。