International Developments in Accounting Assignment 1

- 格式:docx

- 大小:188.35 KB

- 文档页数:11

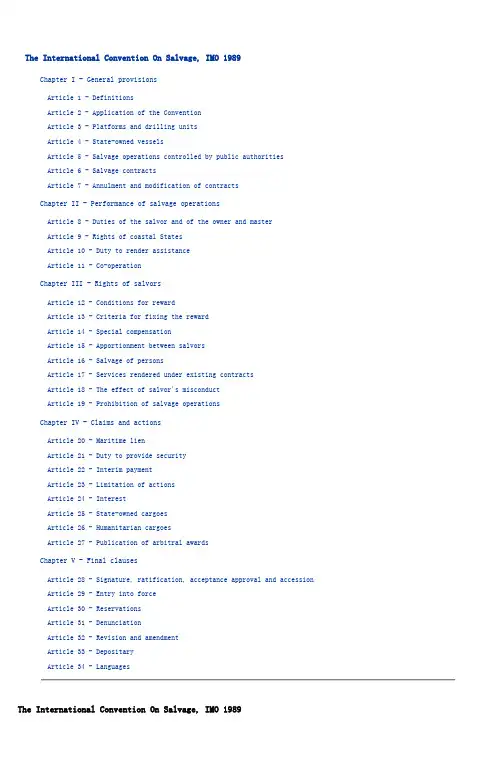

The International Convention On Salvage, IMO 1989Chapter I - General provisionsArticle 1 - DefinitionsArticle 2 - Application of the ConventionArticle 3 - Platforms and drilling unitsArticle 4 - State-owned vesselsArticle 5 - Salvage operations controlled by public authoritiesArticle 6 - Salvage contractsArticle 7 - Annulment and modification of contractsChapter II - Performance of salvage operationsArticle 8 - Duties of the salvor and of the owner and masterArticle 9 - Rights of coastal StatesArticle 10 - Duty to render assistanceArticle 11 - Co-operationChapter III - Rights of salvorsArticle 12 - Conditions for rewardArticle 13 - Criteria for fixing the rewardArticle 14 - Special compensationArticle 15 - Apportionment between salvorsArticle 16 - Salvage of personsArticle 17 - Services rendered under existing contractsArticle 18 - The effect of salvor's misconductArticle 19 - Prohibition of salvage operationsChapter IV - Claims and actionsArticle 20 - Maritime lienArticle 21 - Duty to provide securityArticle 22 - Interim paymentArticle 23 - Limitation of actionsArticle 24 - InterestArticle 25 - State-owned cargoesArticle 26 - Humanitarian cargoesArticle 27 - Publication of arbitral awardsChapter V - Final clausesArticle 28 - Signature, ratification, acceptance approval and accessionArticle 29 - Entry into forceArticle 30 - ReservationsArticle 31 - DenunciationArticle 32 - Revision and amendmentArticle 33 - DepositaryArticle 34 - LanguagesThe International Convention On Salvage, IMO 1989THE STATES PARTIES TO THE PRESENT CONVENTIONRECOGNIZING the desirability of determining by agreement uniform international rules regarding salvage operations,NOTING that substantial developments, in particular the increased concern for the protection of the environment, have demonstrated the need to review the international rules presently contained in the Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules of Law relating to Assistance and Salvage at Sea, done at Brussels, 23 September 1910,CONSCIOUS of the major contribution which efficient and timely salvage operations can make to the safety of vessels and other property in danger and to the protection of the environment,CONVINCED of the need to ensure that adequate incentives are available to persons who undertake salvage operations in respect of vessels and other property in danger,HAVE AGREED as follows:Chapter I - General provisionsArticle 1 - DefinitionsFor the purpose of this Convention:(a) Salvage operation means any act or activity undertaken to assist a vessel or any other property in danger in navigable waters or in any other waters whatsoever.(b) Vessel means any ship or craft, or any structure capable of navigation.(c) Property means any property not permanently and intentionally attached to the shoreline and includes freight at risk.(d) Damage to the environment means substantial physical damage to human health or to marine life or resources in coastal or inland waters or areas adjacent thereto, caused by pollution, contamination, fire, explosion or similar major incidents.(e) Payment means any reward, remuneration or compensation due under this Convention.(f) Organization means the International Maritime Organization.(g) Secretary-General means the Secretary-General of the Organization.Article 2 - Application of the ConventionThis Convention shall apply whenever judicial or arbitral proceedings relating to matters dealt with in this Convention are brought in a State Party.Article 3 - Platforms and drilling unitsThis Convention shall not apply to fixed or floating platforms or to mobile offshore drilling units when such platforms or units are on location engaged in the exploration, exploitation or production of sea-bed mineral resources.Article 4 - State-owned vessels1. Without prejudice to article 5, this Convention shall not apply to warships or other non-commercial vessels owned or operated by a State and entitled, at the time of salvage operations, to sovereign immunity under generally recognized principles of international law unless that State decides otherwise.2. Where a State Party decides to apply the Convention to its warships or other vessels described in paragraph 1, it shall notify the Secretary-General thereof specifying the terms and conditions of such application.Article 5 - Salvage operations controlled by public authorities1. This Convention shall not affect any provisions of national law or any international convention relating to salvage operations by or under the control of public authorities.2. Nevertheless, salvors carrying out such salvage operations shall be entitled to avail themselves of the rights and remedies provided for in this Convention in respect of salvage operations.3. The extent to which a public authority under a duty to perform salvage operations may avail itself of the rights and remedies provided for in this Convention shall be determined by the law of the State where such authority is situated.Article 6 - Salvage contracts1. This Convention shall apply to any salvage operations save to the extent that a contract otherwise provides expressly or by implication.2. The master shall have the authority to conclude contracts for salvage operations on behalf of the owner of the vessel. The master or the owner of the vessel shall have the authority to conclude such contracts on behalf of the owner of the property on board the vessel.3. Nothing in this article shall affect the application of article 7 nor duties to prevent or minimize damage to the environment. Article 7 - Annulment and modification of contractsA contract or any terms thereof may be annulled or modified if:(a) the contract has been entered into under undue influence or the influence of danger and its terms are inequitable; or(b) the payment under the contract is in an excessive degree too large or too small for the services actually rendered. Chapter II - Performance of salvage operationsArticle 8 - Duties of the salvor and of the owner and master1. The salvor shall owe a duty to the owner of the vessel or other property in danger:(a) to carry out the salvage operations with due care;(b) in performing the duty specified in subparagraph (a), to exercise due care to prevent or minimize damage to the environment;(c) whenever circumstances reasonably require, to seek assistance from other salvors; and(d) to accept the intervention of other salvors when reasonably requested to do so by the owner or master of the vessel or other property in danger; provided however that the amount of his reward shall not be prejudiced should it be found that such a request was unreasonable.2. The owner and master of the vessel or the owner of other property in danger shall owe a duty to the salvor:(a) to co-operate fully with him during the course of the salvage operations;(b) in so doing, to exercise due care to prevent or minimize damage to the environment; and(c) when the vessel or other property has been brought to a place of safety, to accept redelivery when reasonably requested by the salvor to do so.Article 9 - Rights of coastal StatesNothing in this Convention shall affect the right of the coastal State concerned to take measures in accordance with generally recognized principles of international law to protect its coastline or related interests from pollution or the threat of pollution following upon a maritime casualty or acts relating to such a casualty which may reasonably be expected to result in major harmful consequences, including the right of a coastal State to give directions in relation to salvage operations.Article 10 - Duty to render assistance1. Every master is bound, so far as he can do so without serious danger to his vessel and persons thereon, to render assistance to any person in danger of being lost at sea.2. The States Parties shall adopt the measures necessary to enforce the duty set out in paragraph 1.3. The owner of the vessel shall incur no liability for a breach of the duty of the master under paragraph 1.Article 11 - Co-operationA State Party shall, whenever regulating or deciding upon matters relating to salvage operations such as admittance to ports of vessels in distress or the provision of facilities to salvors, take into account the need for co-operation between salvors, other interested parties and public authorities in order to ensure the efficient and successful performance of salvage operations for the purpose of saving life or property in danger as well as preventing damage to the environment in general.Chapter III - Rights of salvorsArticle 12 - Conditions for reward1. Salvage operations which have had a useful result give right to a reward.2. Except as otherwise provided, no payment is due under this Convention if the salvage operations have had no useful result.3. This chapter shall apply, notwithstanding that the salved vessel and the vessel undertaking the salvage operations belong to the same owner.Article 13 - Criteria for fixing the reward1. The reward shall be fixed with a view to encouraging salvage operations, taking into account the following criteria without regard to the order in which they are presented below:(a) the salved value of the vessel and other property;(b) the skill and efforts of the salvors in preventing or minimizing damage to the environment;(c) the measure of success obtained by the salvor;(d) the nature and degree of the danger;(e) the skill and efforts of the salvors in salving the vessel, other property and life;(f) the time used and expenses and losses incurred by the salvors;(g) the risk of liability and other risks run by the salvors or their equipment;(h) the promptness of the services rendered;(i) the availability and use of vessels or other equipment intended for salvage operations;(j) the state of readiness and efficiency of the salvor's equipment and the value thereof.2. Payment of a reward fixed according to paragraph 1 shall be made by all of the vessel and other property interests in proportion to their respective salved values. However, a State Party may in its national law provide that the payment of a reward has to be made by one of these interests, subject to a right of recourse of this interest against the other interests for their respective shares. Nothing in this article shall prevent any right of defence.3. The rewards, exclusive of any interest and recoverable legal costs that may be payable thereon, shall not exceed the salved value of the vessel and other property.Article 14 - Special compensation1. If the salvor has carried out salvage operations in respect of a vessel which by itself or its cargo threatened damage to the environment and has failed to earn a reward under article 13 at least equivalent to the special compensation assessable in accordance with this article, he shall be entitled to special compensation from the owner of that vessel equivalent to his expenses as herein defined.2. If, in the circumstances set out in paragraph 1, the salvor by his salvage operations has prevented or minimized damage to the environment, the special compensation payable by the owner to the salvor under paragraph 1 may be increased up to a maximum of 30% of the expenses incurred by the salvor. However, the tribunal, if it deems it fair and just to do so and bearing in mind the relevant criteria set out in article 13, paragraph 1, may increase such special compensation further, but in no event shall the total increase be more than 100% of the expenses incurred by the salvor.3. Salvor's expenses for the purpose of paragraphs 1 and 2 means the out-of-pocket expenses reasonably incurred by the salvor in the salvage operation and a fair rate for equipment and personnel actually and reasonably used in the salvage operation, taking into consideration the criteria set out in article 13, paragraph 1 (h), (i) and (j).4. The total special compensation under this article shall be paid only if and to the extent that such compensation is greater than any reward recoverable by the salvor under article 13.5. If the salvor has been negligent and has thereby failed to prevent or minimize damage to the environment, he may be deprived of the whole or part of any special compensation due under this article.6. Nothing in this article shall affect any right of recourse on the part of the owner of the vessel.Article 15 - Apportionment between salvors1. The apportionment of a reward under article 13 between salvors shall be made on the basis of the criteria contained in that article.2. The apportionment between the owner, master and other persons in the service of each salving vessel shall be determined by the law of the flag of that vessel. If the salvage has not been carried out from a vessel, the apportionment shall be determined by the law governing the contract between the salvor and his servants.Article 16 - Salvage of persons1. No remuneration is due from persons whose lives are saved, but nothing in this article shall affect the provisions of national law on this subject.2. A salvor of human life, who has taken part in the services rendered on the occasion of the accident giving rise to salvage, is entitled to a fair share of the payment awarded to the salvor for salving the vessel or other property or preventing or minimizing damage to the environment.Article 17 - Services rendered under existing contractsNo payment is due under the provisions of this Convention unless the services rendered exceed what can be reasonably considered as due performance of a contract entered into before the danger arose.Article 18 - The effect of salvor's misconductA salvor may be deprived of the whole or part of the payment due under this Convention to the extent that the salvage operations have become necessary or more difficult because of fault or neglect on his part or if the salvor has been guilty of fraud or other dishonest conduct.Article 19 - Prohibition of salvage operationsServices rendered notwithstanding the express and reasonable prohibition of the owner or master of the vessel or the owner of any other property in danger which is not and has not been on board the vessel shall not give rise to payment under this ConventionChapter IV - Claims and actionsArticle 20 - Maritime lien1. Nothing in this Convention shall affect the salvor's maritime lien under any international convention or national law.2. The salvor may not enforce his maritime lien when satisfactory security for his claim, including interest and costs, has been duly tendered or provided.Article 21 - Duty to provide security1. Upon the request of the salvor a person liable for a payment due under this Convention shall provide satisfactory security for the claim, including interest and costs of the salvor.2. Without prejudice to paragraph 1, the owner of the salved vessel shall use his best endeavours to ensure that the owners of the cargo provide satisfactory security for the claims against them including interest and costs before the cargo is released.3. The salved vessel and other property shall not, without the consent of the salvor, be removed from the port or place at which they first arrive after the completion of the salvage operations until satisfactory security has been put up for the salvor's claim against the relevant vessel or property.Article 22 - Interim payment1. The tribunal having jurisdiction over the claim of the salvor may, by interim decision, order that the salvor shall be paid on account such amount as seems fair and just, and on such terms including terms as to security where appropriate, as may be fair and just according to the circumstances of the case.2. In the event of an interim payment under this article the security provided under article 21 shall be reduced accordingly.Article 23 - Limitation of actions1. Any action relating to payment under this Convention shall be time-barred if judicial or arbitral proceedings have not been instituted within a period of two years. The limitation period commences on the day on which the salvage operations are terminated.2. The person against whom a claim is made may at any time during the running of the limitation period extend that period by a declaration to the claimant. This period may in the like manner be further extended.3. An action for indemnity by a person liable may be instituted even after the expiration of the limitation period provided for in the preceding paragraphs, if brought within the time allowed by the law of the State where proceedings are instituted.Article 24 - InterestThe right of the salvor to interest on any payment due under this Convention shall be determined according to the law of the State in which the tribunal seized of the case is situated.Article 25 - State-owned cargoesUnless the State owner consents, no provision of this Convention shall be used as a basis for the seizure, arrest or detention by any legal process of, nor for any proceedings in rem against, non-commercial cargoes owned by a State and entitled, at the time of the salvage operations, to sovereign immunity under generally recognized principles of international law.Article 26 - Humanitarian cargoesNo provision of this Convention shall be used as a basis for the seizure, arrest or detention of humanitarian cargoes donated by a State, if such State has agreed to pay for salvage services rendered in respect of such humanitarian cargoes.Article 27 - Publication of arbitral awardsStates Parties shall encourage, as far as possible and with the consent of the parties, the publication of arbitral awards made in salvage cases.Chapter V - Final clausesArticle 28 - Signature, ratification, acceptance approval and accession1. This Convention shall be open for signature at the Headquarters of the Organization from 1 July 1989 to 30 June 1990 and shall thereafter remain open for accession.2. States may express their consent to be bound by this Convention by:(a) signature without reservation as to ratification, acceptance or approval; or(b) signature subject to ratification, acceptance or approval, followed by ratification, acceptance or approval; or(c) accession.3. Ratification, acceptance, approval or accession shall be effected by the deposit of an instrument to that effect with the Secretary-General.Article 29 - Entry into force1. This Convention shall enter into force one year after the date on which 15 States have expressed their consent to be bound by it.2. For a State which expresses its consent to be bound by this Convention after the conditions for entry into force thereof have been met, such consent shall take effect one year after the date of expression of such consent.Article 30 - Reservations1. Any State may, at the time of signature, ratification, acceptance, approval or accession, reserve the right not to apply the provisions of this Convention:(a) when the salvage operation takes place in inland waters and all vessels involved are of inland navigation;(b) when the salvage operations take place in inland waters and no vessel is involved;(c) when all interested parties are nationals of that State;(d) when the property involved is maritime cultural property of prehistoric, archaeological or historic interest and is situated on the sea-bed.2. Reservations made at the time of signature are subject to confirmation upon ratification, acceptance or approval.3. Any State which has made a reservation to this Convention may withdraw it at any time by means of a notification addressed to the Secretary-General. Such withdrawal shall take effect on the date the notification is received. If the notification states that the withdrawal of a reservation is to take effect on a date specified therein, and such date is later than the date the notification is received by the Secretary-General, the withdrawal shall take effect on such later date.Article 31 - Denunciation1. This Convention may be denounced by any State Party at any time after the expiry of one year from the date on which this Convention enters into force for that State.2. Denunciation shall be effected by the deposit of an instrument of denunciation with the Secretary-General.3. A denunciation shall take effect one year, or such longer period as may be specified in the instrument of denunciation, after the receipt of the instrument of denunciation by the Secretary-General.Article 32 - Revision and amendment1. A conference for the purpose of revising or amending this Convention may be convened by the Organization.2. The Secretary-General shall convene a conference of the States Parties to this Convention for revising or amending the Convention, at the request of eight States Parties, or one fourth of the States Parties, whichever is the higher figure.3. Any consent to be bound by this Convention expressed after the date of entry into force of an amendment to this Convention shall be deemed to apply to the Convention as amended.Article 33 - Depositary1. This convention shall be deposited with the Secretary-General.2. The Secretary-General shall:(a) inform all States which have signed this Convention or acceded thereto, and all Members of the Organization, of:(i) each new signature or deposit of an instrument of ratification, acceptance, approval or accession together with the date thereof;(ii) the date of the entry into force of this Convention;(iii) the deposit of any instrument of denunciation of this Convention together with the date on which it is received and the date on which the denunciation takes effect;(iv) any amendment adopted in conformity with article 32;(v) the receipt of any reservation, declaration or notification made under this Convention;(b) transmit certified true copies of this Convention to all States which have signed this Convention or acceded thereto.3. As soon as this Convention enters into force, a certified true copy thereof shall be transmitted by the Depositary to the Secretary-General of the United Nations for registration and publication in accordance with Article 102 of the Charter of the United Nations.Article 34 - LanguagesThis Convention is established in a single original in the Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish languages, each text being equally authentic.IN WITNESS WHEREOF the undersigned being duly authorized by their respective Governments for that purpose have signed this Convention.DONE AT LONDON this twenty-eighth day of April one thousand nine hundred and eighty-nine.。

ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENTINTERNATIONAL VAT/GST GUIDELINESFebruary 2006CENTRE FOR TAX POLICY AND ADMINISTRATIONINTERNATIONAL VAT/GST GUIDELINESPREFACE1. The spread of Value Added Tax (also called Goods and Services Tax – GST) has been the most important development in taxation over the last half-century. Limited to less than ten countries in the late 1960s it has now been implemented by about 136 countries; and in these countries (including OECD member countries) it typically accounts for one-fifth of total tax revenue. The recognised capacity of VAT to raise revenue in a neutral and transparent manner drew all OECD member countries (except the United States) to adopt this broad based consumption tax. Its neutrality of principle towards international trade also made it the preferred alternative to customs duties in the context of trade liberalisation.2. At the same time as VAT was spreading across the world, international trade in goods and services was expanding rapidly as part of globalisation developments, spurred on by deregulation, privatisation and the communications technology revolution. As a result, the interaction between value added tax systems operated by individual countries has come under greater scrutiny as potential for double taxation and unintentional non-taxation has increased.3. When international trade was characterised largely by trade in goods, collection of taxes was generally undertaken by customs authorities, and when services were primarily traded within domestic markets, there was little need for global attention to be paid to the interaction between national consumption tax rules. That situation has changed dramatically in recent years and the absence of internationally agreed approaches, which can be traced back to that lack of need, is now leading to significant difficulties for both business and governments, particularly for the international trade in services and intangibles, and increasingly for the trade in goods.4. Even though the question remains difficult –and sometimes controversial- for interstate trade within federations or within economically integrated areas, the destination principle (i.e. taxation in the jurisdiction of consumption by zero rating of exports and taxation of imports) is the international norm. The issues therefore arise primarily from the practical difficulty of determining, for each transaction (i.e. the sale of a good, a right or a service), the jurisdiction where consumption is deemed to take place and therefore where it should be taxed. In addition, it should be borne in mind that value added tax systems are designed to tax final consumption and as such, in most cases it is only consumers who should actually bear the tax burden. Indeed, the tax is levied, ultimately, on consumption and not on intermediate transactions between firms as tax charged on these purchases is, in principle, fully deductible. This feature gives the tax its main characteristic of neutrality in the value chain and towards international trade.5. Nevertheless, although most countries have adopted similar principles for the operation of their value added tax system, there remain many differences in the way it is implemented, including between OECD member countries. These differences result not only from the continued existence of exemptions and special arrangements to meet specific policy objectives, but also from differences of approaches in the definition of the jurisdiction of consumption and therefore of taxation. In addition, there are a number of variations in the application of value added taxes, and other consumption taxes, including different interpretation of the same or similar concepts; different approaches to time of supply and its interactionwith place of supply; different definitions of services and intangibles and inconsistent treatment of mixed supplies.6. Since the late 1990s, work led by the OECD’s Committee on Fiscal Affairs (CFA) in cooperation with business, revealed that the current international consumption taxes environment, especially with respect to trade in services and intangibles, is creating obstacles to business activity, hindering economic growth and distorting competition. The CFA recognised that these problems, particularly those of double taxation and unintentional non-taxation, were sufficiently significant to require remedies. This situation creates increasing issues for both businesses and tax administrations themselves since local rules cannot be viewed in isolation but must be addressed internationally.7. Businesses are increasingly confronted by distortions of competition that sometimes favour imports over local production or prevent them outsourcing activities as a means of improving their competitiveness. Multi-national businesses are confronted with laws and administrative requirements that may be contradictory from country to country. This generates undue burdens and uncertainties, in particular when they specialise or group certain functions in one particular jurisdiction, such as shared service centres, centralised sales and procurement functions, call centres, data processing and information technology support. Businesses can incur double taxation when two different jurisdictions both tax the same supply, the first one because it is the jurisdiction where the supplier is established and the second one because it is the jurisdiction where the recipient is established. In the case of leasing of goods, for example, a third jurisdiction, i.e. the jurisdiction where the goods are located, may also claim the tax. Uncertainties also arise in situations where, for example, the headquarters of a company established in one country provides supplies to customers in another country where it has a branch (force of attraction). Even if some countries implemented refund schemes of tax incurred by foreign business or registration procedures to achieve the same effect, which are intended in part to address some of the consequences of these different approaches, such schemes are, when they exist, often burdensome, especially for SMEs.8. Tax administrations are often confronted with unintentional non-taxation that mirror the double taxation situations referred to above. Consumption taxes are normally predicated on the basis that businesses are responsible for the proper collection and remittance of the revenue. Complex, unclear or inconsistent rules across jurisdictions are difficult to manage for tax administrations and create uncertainties and high administrative burdens for business, which can lead to reduced compliance levels. In addition, such an environment may also favour tax fraud and evasion.9. The OECD has long held a lead position in dealing with the international aspects of direct taxes. The Organisation has developed internationally recognised instruments such as the Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital and the Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations. Until now, no such instrument was available in the field of consumption taxes. Only the Ottawa Framework Conditions (1998), the Guidelines on Consumption Taxation of Cross-Border Services and Intangible Property in the Context of E-commerce (2001) and Consumption Tax Guidance Series (2003) have been published. The Committee on Fiscal Affairs therefore began work on a set of framework principles on the application of consumption taxes to the trade in international services and intangibles. These principles form the first part of the OECD VAT/GST Guidelines. These principles will be developed in order that countries (both OECD and non-OECD) can implement them in legislation. The table of contents will evolve in the light of experience and will be amended and completed over time.TABLE OF CONTENTSPREFACEGLOSSARYCHAPTER I BASIC PRINCIPLESIntroductionI.A.I.B. Application to International transactionsI.B.1. Services and intangibles(i) Place of Consumption PrinciplesI.B.2. GoodsI.C. Interaction of VAT/GST with Sales, Excise and other Transactional Taxes CHAPTER II APPLICATION OF PLACE OF CONSUMPTION PRINCIPLESIntroductionII.A.II.B. Application of Principles to Services and Intangibles to Achieve Greater Compatibility II.B.1 Defining Place of Consumption(i) Use of Proxies•Performance•Customer Location•OtherII.B.2 Specific treatment for Business to Consumer TransactionsII.B.3 Customer Location IssuesAnnex: Framework (Decision Chart) for Determining Place of TaxationII.C. Tax Collection MethodsII.D. Services Characterisation IssuesII.D.1.Characterisation/Definition of ServicesII.D.2. Mixed and Bundled SuppliesII. E. Application to GoodsCHAPTER III TAXATION OF SERVICES IN SPECIFIC SECTORS III. A. IntroductionTelecommunicationsIII.B.III.C. Electronic CommerceServicesFinancialIII.D.III.E. International TransportGamblingIII.F.CHAPTER IV TIME OF SUPPLY AND ATTRIBUTION RULESIntroductionIV.A.IssuesIV.B.CHAPTER V VALUE OF SUPPLYIntroductionV.A.IssuesV.B.CHAPTER VI COMPLIANCE ISSUESVI.A.IntroductionVI.B. Automated Tax CollectionIV.B.1. CriteriaIV.B.2. ApplicationVI.C. Simplified Administrative ProceduresVI.C.1. Cross-border invoicingRegistrationVI.C.2SimplifiedVI.D. International Tax CooperationVI.D.1. Exchange of InformationVI.D.2. Mutual Administrative AssistanceLegalIssuesVI.D.3.ExchangeforPracticalVI.D.4MethodologiesCHAPTER VII AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATIONIntroductionVII.A.MechanismsRefundVII.B.VII.C. Dispute ResolutionVII.D. Exchange of Information [Mutual Cooperation]InstrumentsVII.E.PossibleVII.E.1. Separate VAT TreatyVII.E.2. New Article in MTCVII.E.3. OECD – Council of Europe Model Convention on Mutual AdministrativeAssistance in Tax Matters** *CHAPTER IBASIC PRINCIPLES1I.A. INTRODUCTION1.There are many differences in the way value added taxes are implemented around the world and across OECD countries. Nevertheless, there are some common core features that can be described as follows:•Value added taxes are taxes on consumption, paid, ultimately, by final consumers.•The tax is levied on a broad base (as opposed to e.g., excise duties that cover specific products);•In principle, business should not bear the burden of the tax itself since there are mechanisms in place that allow for a refund of the tax levied on intermediate transactions between firms.•The system is based on tax collection in a staged process, with successive taxpayers entitled to deduct input tax on purchases and account for output tax on sales. Each business in the supply chain takes part in the process of controlling and collecting the tax, remitting the proportion of tax corresponding to its margin i.e. on the difference between the VAT paid out to suppliers and the VAT charged to customers. In general, OECD countries with value-added taxes impose the tax at all stages and normally allow immediate deduction of taxes on purchases by all but the final consumer.2.These features give value added taxes their main economic characteristic, that of neutrality. The full right to deduction of input tax through the supply chain, with the exception of the final consumer, ensures the neutrality of the tax, whatever the nature of the product, the structure of the distribution chain and the technical means used for its delivery (stores, physical delivery, Internet).3.Value added taxes are also neutral towards international trade according to international norms since they are destination based (even if the rule might be different for transactions made within federations or economically integrated areas). This means that exports are zero rated and imports are taxed on the same basis and with the same rate as local production. Most of the rules currently in place aim therefore at taxing consumption of goods and services within the jurisdiction where consumption takes place. Practical means implemented to this end are nevertheless diverse across countries, which can, in some instances, lead to double or involuntary non-taxation, and uncertainties for both business and tax administrations.1 Germany expressed its reservation on these principles. Luxembourg expressed its reservation on the first principle referred in paragraph 14 (“For consumption tax purposes internationally traded services and intangibles should be taxed according to the rules of the jurisdiction of consumption”).4.Sales tax systems, although they work differently in practice, also set out to tax consumption of goods, and to some extent services, within the jurisdiction of consumption. To this end, their implementation also aims at keeping it neutral towards international trade. However, in most sales tax systems, businesses do incur irrecoverable sales tax and, if they subsequently export goods, there will be an element of sales tax embedded in the price.I.B. APPLICATION TO INTERNATIONAL TRANSACTIONS5.For the international trade in goods there is a commonly held principle that exports should be exempted and imports should be taxed. This is relatively simple to apply, although even here, complexities of globalisation mean that problems can arise. However, for the international trade in services and intangibles there are no such commonly held principles. Thus, the variations by governments in the application of consumption taxes to this increasing trade have led to obstacles to business activity and distortions of competition significant enough to justify the design of common principles. There is also a shared view, both by governments and business, that the neutrality principle described above should be kept as an objective in the design and implementation of VAT/GST Guidelines. The following principles aim mainly at ensuring that transactions are taxed only once and in a single, clearly defined jurisdiction in order to avoid uncertainties, double taxation or involuntary non-taxation.6.The development of e-commerce in the late 1990s led governments to adopt several principles in the field of consumption taxes2. Although they were designed in the context of e-commerce taxation, they remain valid for the more global interaction of consumption tax systems and broadly reflect the philosophy of the existing tax rules in most countries. In addition, the Ottawa Framework Conditions specify that the taxation principles that guide governments in relation to conventional commerce should not be different than those applicable to electronic commerce. These principles can be summarized as follows:•Neutrality: Taxation should seek to be neutral and equitable between forms of commerce.Business decisions should be motivated by economic rather than tax considerations.Taxpayers in similar situations carrying out similar transactions should be subject to similarlevels of taxation.•Efficiency: Compliance costs for taxpayers and administrative costs for the tax authorities should be minimized as far as possible;•Certainty and simplicity: The tax rules should be clear and simple to understand so that taxpayers can anticipate the tax consequences of a transaction, including knowing when, where and how the tax is to be accounted;•Effectiveness and fairness: Taxation should produce the right amount of tax at the right time. The potential for tax evasion and avoidance should be minimized while keeping counter-acting measures proportionate to risks involved;•Flexibility: The systems for taxation should be flexible and dynamic to ensure that they keep pace with technological and commercial developments;2 The Ottawa Framework Conditions were endorsed by Ministers in October 19987.Rules for the consumption taxation of cross-border trade should result in taxation in the jurisdiction where consumption takes place and international consensus should be sought on circumstances under which supplies are held to be consumed in a jurisdiction.8.As regards value added taxes, an additional principle can be established from the general functioning of those taxes: except where explicitly designed, i.e. when several operations are explicitly exempted (input taxed) like financial services, or excluded from the application of the value added taxes, like operations not effected for consideration, the tax burden should not lie on taxable business but on the final consumer.I.B.1. SERVICES AND INTANGIBLES9.The above mentioned general principles can be adapted to the cross-border trade in services and intangibles as follows, for both business to business and business to consumer transactions:•For consumption tax purposes internationally traded services and intangibles should be taxed according to the rules of the jurisdiction of consumption;•The burden of value added taxes themselves should not lie on taxable businesses except where explicitly provided for in legislation.10.In this context, the words “except where explicitly provided” mean that countries may legitimately place a value added tax burden on business. Indeed, this is frequently the case as the following examples illustrate:•Where transactions made by the taxpayer are exempt because the tax base of the outputs is difficult to assess (i.e., many financial services) or for policy reasons (health care, education,culture).•Tax legislation may also impose value added tax on businesses to secure effective taxation of final consumption. This will be the case when the taxpayer makes transactions that fall outside the scope of the tax (e.g., transactions without consideration) or the input tax relatesto purchases that are not wholly used for furtherance of taxable business activity.•Countries also provide legislation that disallows input tax recovery where explicit administrative obligations are not met (e.g., insufficient evidence to support input tax deduction).11.For the purposes of these principles however, any such imposition of value added tax on business should be clear and explicit within the legislative framework for the tax.12.As with many other taxes, value added taxes impose compliance costs on business. It is not the intention of these principles to suggest that compliance costs should not be borne by business, but rather that, business should not incur irrecoverable value added tax (other than within the sort of exceptions exemplified in paragraph 10).CHAPTER III TAXATION OF SERVICES IN SPECIFIC SECTORSIII.C. Electronic CommerceA. Guidelines on the Definition of the Place of ConsumptionIntroduction1.In 1998, OECD Ministers welcomed a number of Taxation Framework Conditions relating to the consumption taxation of electronic commerce in a cross-border trade environment, including:i.In order to prevent double taxation, or unintentional non-taxation, rules for the consumptiontaxation of cross-border trade should result in taxation in the jurisdiction where consumption takes place.ii.For the purpose of consumption taxes, the supply of digitised products should not be treated as a supply of goods.iii.Where businesses acquire services and intangible property from a non-resident vendor, consideration should be given to the use of reverse charge, self-assessment or other equivalentmechanism.2.The Guidelines below are intended to achieve the practical application of the Taxation Framework Conditions in order to prevent double taxation or unintentional non-taxation, particularly in the context of international cross-border electronic commerce. Member countries are encouraged to review existing national legislation to determine its compatibility with these Guidelines and to consider any legislative changes necessary to align such legislation with the objectives of the Guidelines. At the same time, Member countries should consider any control and enforcement measures necessary for their implementation.Business-to-business transactions3.The place of consumption for cross-border supplies of services and intangible property that are capable of delivery from a remote location made to a non-resident business recipient3should be the jurisdiction in which the recipient has located its business presence4.3This will normally include a “taxable person” or an entity who is registered or is obliged to register and account for tax. This may also include another entity that is identified for tax purposes.4 The “business presence” is, in principle, the establishment (for example, headquarters, registered office, or a branch of the business) of the recipient to which the supply is made.4.In certain circumstances, countries may, however, use a different criterion to determine the actual place of consumption, where the application of the approach in paragraph 3 would lead to a distortion of competition or avoidance of tax5.Business-to-private consumer transactions5.The place of consumption for cross-border supplies of services and intangible property that are capable of delivery from a remote location made to a non-resident private recipient6should be the jurisdiction in which the recipient has their usual residence7.Application86.In the context of value-added or other general consumption tax systems, these Guidelines are intended to define the place of consumption (and so the place of taxation) for the international cross-border supply of services and intangible property by non-resident vendors/suppliers that are not otherwise registered and are not required to register in the destination jurisdiction under existing mechanisms910.7.These Guidelines apply to the cross-border supply of services and intangible property, particularly in the context of international cross-border electronic commerce, that are capable of delivery from a remote location.8.The Guidelines do not, therefore, apply to services which are not capable of direct delivery froma remote location (for example, hotel accommodation, transportation or vehicle rental). Nor are they applicable in circumstances where the place of consumption may be readily ascertained, as is the case where a service is performed in the physical presence of both the service provider and the customer (for example, hairdressing), or when the place of consumption can more appropriately be determined by reference to a particular criterion (for example, services related to particular immovable property or goods). Finally, it is recognised that specific types of services, for example, some telecommunications services, may require more specific approaches to determine their place of consumption 115 Such an approach should normally be applied only in the context of a reverse charge or self-assessment mechanism.6 In other words, a “non-taxable person” or an entity not registered and not obliged to register and account for tax.7 It is recognised that implementing this Guideline will not always result in taxation in the actual place of consumption. Under a “pure” place of consumption test, intangible services are consumed in the place where the customer actually uses the services. However, the mobility of communications is such that to apply a pure place of consumption test would lead to a significant compliance burden for vendors.8In accordance with the Ottawa Taxation Framework Conditions, specific measures adopted in relation to the placeof taxation by a group of countries that is bound by a common legal framework for their consumption tax systems may, of course, apply to transactions between those countries.9While these Guidelines are not intended to apply to sub-national value-added and general consumption taxes, attention should be given to the issues presented, in the international context, relating to these taxes.10The objective is to ensure certainty and simplicity for businesses and tax administrations, as well as neutrality via equivalent tax implications for the same products in the same market (i.e.avoiding competitive distortions through unintentional non-taxation).11When such specific approaches are used, the Working Party recognises the need for further work and for international co-ordination of such arrangements to avoid double or unintentional non-taxation.B. Recommended Approaches to the Practical Application of the Guidelines on the Definition of the Place of ConsumptionIntroduction9.Three tax collection mechanisms are typically used in consumption tax systems: registration, reverse charge/self-assessment, and collection of tax by customs authorities on importation of tangible goods. Under a registration system, the vendor of goods and services registers with the tax authority and, depending on the design of the tax, either is liable to pay the tax due on the transaction to the tax authority, or collects the tax payable by the customer and remits it to the tax authority. Under the reverse charge/self-assessment system, the customer pays the tax directly to the tax authority. The third approach, collection of the tax on the importation of tangible goods by customs authorities, is common to virtually all national consumption tax systems where national borders exist for customs purposes.10.Since registration and self-assessment/reverse charge mechanisms are currently in use in the majority of consumption tax systems, they represent a logical starting point in determining which approaches are most appropriate to apply in the context of electronic commerce transactions involving cross-border supplies of services and intangible property.11.While emerging technology promises to assist in developing innovative approaches to tax collection, and the global nature of electronic commerce suggests that collaborative approaches between revenue authorities will become increasingly important, Member countries agree that in the short term, the two traditional approaches to tax collection remain the most promising. However, Member countries agree that their application varies depending on the type of transaction.Recommended approachesBusiness-to-business transactions12.In the context of cross-border business-to-business (B2B) transactions (of the type referred to in the Guidelines), it is recommended that in cases where the supplying business is not registered and is not required to be registered for consumption tax in the country of the recipient business, a self-assessment or reverse charge mechanism should be applied where this type of mechanism is consistent with the overall design of the national consumption tax system.13.In the context of B2B cross-border transactions in services and intangible property the self-assessment/reverse charge mechanism has a number of key advantages. Firstly, it can be made effective since the tax authority in the country of consumption can verify and enforce compliance. Secondly, given that it applies to the customer, the compliance burden on the vendor or provider of the service or intangible product is minimal. Finally, it reduces the revenue risks associated with the collection of tax by non-resident vendors whether or not that vendor’s customers are entitled to deduct the tax or recover it through input tax credits.14.Member countries may also wish to consider dispensing with the requirement to self-assess or reverse charge the tax in circumstances where the customer would be entitled to fully recover it through deduction or input tax credit.Business-to-consumer transactions15.Effective tax collection in respect of business-to-consumer (B2C) cross-border transactions of services and intangible property presents particular challenges. Member countries recognise that no single option, of those examined as part of the international debate, is without significant difficulties. In the medium term, technology-based options offer much potential to support new methods of tax collection. Member countries are expressly committed to further detailed examination of this potential to agree on how it can best be supported and developed.16.In the interim, where countries consider it necessary, for example because of the potential for distortion of competition or significant present or future revenue loss, a registration system (where consistent with the overall design of the national consumption tax system) should be considered to ensure the collection of tax on B2C transactions.17.Where countries feel it appropriate to put into effect a registration system in respect of non-resident vendors of services and intangible property not currently registered and not required to be registered for that country’s tax, it is recommended that a number of considerations be taken into account. Firstly, consistent with the effective and efficient collection of tax, countries should ensure that the potential compliance burden is minimised. For example, countries may wish to consider registration regimes that include simplified registration requirements for non-resident suppliers (including electronic registration and declaration procedures), possibly combined with limitations on the recovery of input tax in order to reduce risks to the tax authority. Secondly, countries should seek to apply registration thresholds in a non-discriminatory manner. Finally, Member countries should consider appropriate control and enforcement measures to ensure compliance, and recognise, in this context, the need for enhanced international administrative co-operation.。

你更喜欢国内新闻还是国际新闻英语作文全文共3篇示例,供读者参考篇1Do I Prefer Domestic or International News?As a student, I find myself constantly bombarded with news from all around the world. Whether it's through social media, online news outlets, or traditional television and newspapers, there is an endless stream of information vying for my attention. However, amidst this deluge of news, I often find myself grappling with the question – do I prefer domestic or international news?On one hand, domestic news holds a certain familiarity and relevance to my daily life. After all, the events and issues unfolding within my own country have a direct impact on the society I inhabit. Local politics, economic developments, and cultural happenings shape the very fabric of my immediate surroundings. There's a certain comfort in staying informed about the goings-on in my own backyard, as it allows me to better understand and navigate the world around me.Yet, there's an undeniable allure to international news as well. The world has become increasingly interconnected, and the events unfolding on the global stage often have far-reaching implications that transcend borders. From geopolitical tensions to environmental crises, international news offers a broader perspective on the challenges and triumphs that humanity faces collectively.One of the most captivating aspects of international news is the opportunity to explore different cultures, traditions, and ways of life. Through the lens of foreign correspondents and global media outlets, I'm able to catch glimpses of societies vastly different from my own. This exposure not only fosters a greater understanding and appreciation for diversity but also challenges me to question my own assumptions and biases.Moreover, international news often sheds light on issues that may be overlooked or underreported in domestic coverage. Human rights violations, conflicts in far-flung regions, and the plight of marginalized communities around the world – these are stories that deserve to be told and heard, even if they don't directly affect my immediate surroundings.However, it would be remiss to discount the importance of domestic news entirely. After all, the decisions made by our localleaders and the issues facing our communities have a profound impact on our day-to-day lives. From policy changes that affect our education and healthcare systems to local infrastructure developments, domestic news keeps us informed and engaged as citizens.Furthermore, domestic news often delves into the nuances and complexities of issues that may be oversimplified or generalized in international coverage. By staying attuned to local reporting, I can gain a deeper understanding of the unique challenges and perspectives that shape the discourse within my own country.Ultimately, I believe that striking a balance between domestic and international news is crucial for developing awell-rounded understanding of the world around us. While domestic news provides me with the context and relevance to navigate my immediate surroundings, international news broadens my horizons and reminds me of the interconnectedness of our global community.In an age where information is abundant and readily available, it's tempting to focus solely on the news that aligns with our personal interests or reinforces our existing beliefs. However, true intellectual growth and understanding require usto step outside of our comfort zones and engage with diverse perspectives, both local and global.As a student, I strive to approach news consumption with an open mind and a willingness to learn. Whether I'm delving into the intricacies of local politics or exploring the richness of distant cultures, each piece of news offers an opportunity for personal growth and a deeper appreciation for the complexities of our world.Perhaps the true value of news lies not in the distinctions between domestic and international, but rather in the stories themselves – stories that challenge us, inspire us, and ultimately, connect us to the greater human experience. By embracing both local and global perspectives, we can cultivate a more nuanced and empathetic understanding of the world, and in doing so, become more informed and engaged citizens.In the end, my preference for domestic or international news is not an either/or proposition. Rather, it's a delicate dance between the familiar and the unfamiliar, the local and the global, the personal and the universal. By immersing myself in both realms, I can better appreciate the intricate tapestry of our shared human experience, one thread at a time.篇2Do I Prefer Domestic or International News?As a student living in the modern, globalized world, I am constantly bombarded with news from both domestic and international sources. Every day, I scroll through my social media feeds and news apps, taking in the latest headlines and current events unfolding around me. While I certainly value being informed about happenings in my own country, I find myself increasingly drawn to international news coverage. In my opinion, following global affairs is not only more interesting, but also more important for developing a well-rounded worldview.To begin with, international news exposes me to diverse perspectives that simply cannot be found in domestic reporting alone. News outlets based in my home country inevitably have an ingrained cultural bias, viewing world events primarily through the lens of how they impact our nation. However, by reading publications from other countries, I gain insight into how the same issues are perceived from radically different vantage points around the globe. This opens my eyes to new ideas and ways of thinking that challenge my assumptions.For example, consider the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. While domestic media focuses heavily on the military intervention by Russia, geopolitical implications for my country's interests, and the civilians caught in the crossfire, international journalists provide crucial context about the deeper historical tensions, ethnic divisions, and political power dynamics that sparked the crisis in the first place. Israeli newspapers humanize the conflict through stories of Jewish Ukrainian refugees escaping violence, while Indian coverage emphasizes the plight of thousands of stranded students desperate to return home from the war zone. By combining these varied narratives, I can start to piece together a more complete picture.On a broader level, paying close attention to international current events helps me understand the complex interconnectivity of our modern world. The COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, cyber attacks, trade disputes, refugee crises - these are all issues that transcend borders and impact the global population. Through international reporting on things like supply chain disruptions in China or droughts in Somalia, I learn how circumstances on the other side of the world can have very real consequences for my daily life as well. No nation is truly an island anymore in this hyper-connected era.Moreover, international news expands my knowledge about the immense diversity across world cultures, value systems, and ways of life. While my domestic news understandably focuses on the societal norms and current events most relevant to my own country, venturing into international coverage introduces me to the rich tapestries of indigenous communities in the Amazon, nomadic tribes in the Sahara, bustling megacities in India, and so much more. Every country's unique history, traditions, art, music, and human stories are on full display. Reading about the joy of Chilean fans celebrating their unconventional "keeper" scoring a goal at the World Cup or the struggles of Afghan girls篇3Do I Prefer Domestic or International News?As a student living in an increasingly globalized world, the question of whether I prefer domestic or international news is an intriguing one. On one hand, local and national news directly impacts my day-to-day life, shaping the political, economic, and social landscape around me. On the other hand, international headlines offer a window into the wider world, allowing me to understand the complex interconnections and events shaping our global community. Ultimately, I find myself drawn to a balanced diet of both domestic and international coverage.Let's start with the case for domestic news. As a citizen of my country, it's crucial for me to stay informed about the policies, leaders, and developments that will shape my homeland's future. From presidential elections to economic policies, supreme court rulings to environmental regulations, the decisions made within my nation's borders have a tangible impact on my life. By following domestic political news closely, I can hold my elected officials accountable and make informed decisions when I step into the voting booth.Moreover, local news hits even closer to home. The crime reports, community initiatives, school board decisions, and municipal politics covered in my city's newspapers and television broadcasts directly influence the world I inhabit every day. Knowing about a road closure can help me plan my commute, while being aware of a new development project allows me to voice my opinion on how my neighborhood evolves. Domestic news is intricately woven into the fabric of my daily existence.However, I would be remiss if I ignored the immense value of international news coverage. In our modern, interconnected age, events across the globe can ripple outward and impact my life in ways I may not immediately realize. The COVID-19 pandemic starkly illustrated how a localized outbreak could rapidly escalateinto a worldwide crisis, disrupting economies, closing borders, and transforming daily life for billions. By staying informed about international developments, I can better anticipate how global forces may shape my future.Beyond pragmatic concerns, consuming international news also expands my worldview and cultivates a sense of global citizenship. Reading about the political upheavals in nations across the world, the human rights struggles of oppressed peoples, and the environmental battles being waged on every continent motivates me to consider my role in creating a more just and sustainable world for all. International news coverage introduces me to diverse cultures, beliefs, and perspectives, challenging me to transcend my inherent biases and ethnocentrism.Additionally, many of the most pressing issues facing humanity today – climate change, terrorism, refugee crises, pandemic diseases, cyber threats – are inherently global in scope. To truly understand the complexities and potential solutions surrounding these challenges, I need the vantage point that international news sources provide. From following the latest United Nations reports to reading first-hand accounts from journalists embedded in global hotspots, International newsilluminates the intricate web of interlocking challenges and opportunities that define our modern era.Of course, the lines between domestic and international news are increasingly blurred in today's world. The policies and actions of my government on the world stage reverberate globally, while international power dynamics and alliances shape my nation's trajectory. Economic forces flow across borders with ease, and cyber threats know no geographical boundaries. To be a truly informed citizen, I need a firm grasp of both the internal and external forces shaping my society.Ultimately, I don't see domestic and international news as an either/or proposition, but rather as complementary pieces of a larger informational puzzle. To truly understand the complex, kaleidoscopic world we live in, I need a panoramic view that accounts for both the hyper-local and the transcontinentally global. My ideal media diet balances coverage of the municipal decisions impacting my neighborhood with analysis of the geopolitical machinations of world powers. I strive to be both a well-informed local citizen and a globally conscious human being.In practical terms, this means I consume a wide range of reputable news sources spanning multiple mediums. I value thedepth and scrutiny of traditional newspapers and magazines, but also appreciate the speed and multimedia opportunities of online sources. I've curated social media feeds that blend domestic policy journalists with overseas correspondents, enmeshing insight from my home country with perspectives from every corner of the globe. I'm cognizant of the filter bubbles and biases that can emerge when we selectively expose ourselves to information, so I make a point of seeking out sources that challenge my assumptions, introduce viewpoints, and represent a diversity of ideological leanings.Of course, the modern media landscape is a minefield of misinformation, partisan spin, and outright falsehoods at both the domestic and international level. Developing robust media literacy skills – questioning sources, scrutinizing motivations, fact-checking assertions, and consulting topic experts – has become crucial for any news consumer. I'm learning to be a discerning skeptic, interrogating every claim and comfortable with inhabiting the ambiguities that often arise when complex issues are viewed through divergent cultural lenses.In the end, I don't think the choice between domestic and international news is a binary one. The two spheres are inextricably intertwined in our globalized world. My goal is tobecome an informed global citizen while still staying abreast of the local issues directly impacting my daily life. By seeking out quality journalism from a balance of sources, questioning the narratives I'm presented with, and remaining endlessly curious about the world around me, I hope to simultaneously be awell-informed local citizen and a globally conscious human being. It's an ongoing journey of learning, questioning, and contextualizing the fire-hose of information we all swim in every day. I may not always get the balance right, but I'll keep striving to expand my knowledge and perspective by drawing insight from credible news sources that range from my neighborhood's community paper all the way to the global stage.。

外贸英语书信完全齐头式格式的范文全文共3篇示例,供读者参考篇1Ellsworth Community College1234 Main StreetEllsworth, Iowa 50075United StatesApril 2, 2024Ms. Emily JohnsonExport ManagerBritish Lighting Corporation456 Coventry RoadBirmingham, B26 3QQUnited KingdomDear Ms. Johnson,INVITATION TO PARTICIPATE IN INTERNATIONAL TRADE FAIRI am writing to you on behalf of the International Business Students Association (IBSA) at Ellsworth Community College. Our association is organizing the annual International Trade Fair, which will be held on the college campus from May 15-17, 2024.The International Trade Fair is a highly anticipated event that provides an excellent platform for companies to showcase their products and services to a diverse audience, including students, faculty, local businesses, and the general public. It is an opportunity to forge new partnerships, explore potential collaborations, and gain valuable insights into the latest trends and developments in various industries.As one of the leading manufacturers of lighting solutions in the United Kingdom, we believe that your participation in this event would be highly beneficial for both your company and our students. Your presence would not only allow you to promote your innovative products but also provide our students with a unique opportunity to learn from industry professionals and gain practical experience in international trade.The International Trade Fair will feature a wide range of activities, including:Exhibition Booths: Companies will have the opportunity to set up booths to display and demonstrate their products andservices. This will allow visitors to interact directly with your representatives and gain first-hand knowledge about your offerings.Networking Sessions: Dedicated networking sessions will be organized to facilitate connections between exhibitors, students, and other attendees. These sessions will provide a platform for exchanging ideas, exploring potential collaborations, and building professional relationships.Seminars and Workshops: Industry experts, including representatives from participating companies, will be invited to deliver seminars and conduct workshops on various topics related to international trade, marketing, logistics, and business operations.Cultural Performances and Activities: To showcase the diversity of our campus and foster cross-cultural understanding, the event will feature cultural performances, traditional cuisine, and interactive activities from different countries represented by our students and exhibitors.We would be honored to have British Lighting Corporation participate in this prestigious event. Your involvement would not only contribute to the success of the International Trade Fair butalso provide invaluable learning experiences for our students, who are the future leaders of the global business community.To confirm your participation, please complete the enclosed registration form and return it to us by April 30, 2024. Should you have any further questions or require additional information, please do not hesitate to contact me or our event coordinator, Ms. Sarah Thompson, at**********************.Thank you for considering our invitation. We look forward to welcoming you and your team to the Ellsworth Community College International Trade Fair.Sincerely,Michael DavisPresidentInternational Business Students AssociationEllsworth Community College*********************************.eduEnclosure: Registration Form篇2Ms. Jane SmithExport ManagerAcme Electronics, Inc.123 Industry WayElectri-City, CA 90089USAApril 2, 2024Subject: Inquiry about Summer Internship OpportunityDear Ms. Smith,I am a junior at Central University, pursuing a Bachelor's degree in International Business with a concentration in Export Operations and Trade Compliance. Through our career services office, I learned about the potential summer internship opportunity at your esteemed company, and I am writing to express my sincere interest in being considered for the same.With a keen interest in international trade and a strong academic record, I believe I possess the necessary skills and qualifications to contribute meaningfully to your organizationduring the internship period. My coursework has provided me with a solid foundation in areas such as export documentation, logistics, and trade regulations, equipping me with the knowledge required to navigate the complexities of the global business environment.During my time at the university, I have actively participated in various extracurricular activities that have honed my leadership, teamwork, and communication abilities. As the vice president of the International Business Club, I have organized several panel discussions and networking events, fostering valuable connections with industry professionals and gaining insights into the practical aspects of international trade.Furthermore, I have completed two internships in the past, one at a local import-export firm and another at a freight forwarding company. These experiences have given mehands-on exposure to the intricacies of international shipping, customs clearance, and supply chain management. I am confident that the skills and knowledge acquired during these internships will enable me to contribute effectively to your team from day one.Acme Electronics, Inc. is renowned for its commitment to excellence and innovation in the global electronics industry. I amparticularly drawn to your company's focus on sustainable and ethical business practices, which aligns with my personal values and aspirations. Working alongside your experienced professionals would provide me with invaluable learning opportunities and allow me to further develop my expertise in the field of international trade.Enclosed with this letter is my resume, which provides additional details about my academic achievements, work experience, and extracurricular involvement. I would welcome the opportunity to discuss my qualifications further and address any questions or concerns you may have.Thank you for your time and consideration. I look forward to hearing from you regarding the next steps in the internship application process.Sincerely,[Your Name][Your Address][Your City, State, ZIP][Your Phone Number][Your Email Address]Enclosure: Resume篇3Samantha Robertson12 Cedar AvenueBloomington, IN 47401United StatesApril 2, 2024Ms. Emily WatsonHead of International MarketingAcme Corporation25 Park AvenueNew York, NY 10022United StatesDear Ms. Watson,As an aspiring marketing professional with a keen interest in international business, I am writing to express my sincere admiration for Acme Corporation's impressive global presence and forward-thinking marketing strategies. Your company'sdedication to innovation, customer satisfaction, and sustainable practices has truly set a benchmark in the industry.During my studies at Indiana University, I had the opportunity to delve into various aspects of international marketing, including cross-cultural communication, global supply chain management, and market entry strategies. It was through these courses that I became particularly intrigued by Acme Corporation's remarkable success in navigating the complexities of diverse markets worldwide.I vividly recall the case study we analyzed on your company's recent expansion into the Southeast Asian market. The strategic approach you employed, from conducting comprehensive market research to tailoring your products and marketing campaigns to resonate with local cultural nuances, was truly remarkable. The seamless integration of digital and traditional marketing channels, coupled with a strong emphasis on corporate social responsibility initiatives, demonstrated your company's commitment to building long-lasting relationships with customers and communities alike.Furthermore, I was thoroughly impressed by Acme Corporation's unwavering dedication to sustainability and ethical business practices. Your initiatives to reduce carbon footprint,support local communities, and promote fair labor practices throughout your global supply chain have set an exemplary standard for corporate responsibility. As a firm believer in the power of business to drive positive change, I find your company's values and actions truly inspiring.In addition to my academic pursuits, I have had the opportunity to gain practical experience through various internships and extracurricular activities. During my internship at a local advertising agency, I worked closely with a team responsible for developing multicultural marketing campaigns for various clients. This experience allowed me to hone my skills in market research, creative ideation, and campaign execution, while also cultivating a deep appreciation for the nuances of cross-cultural communication.Moreover, as the president of the International Business Club at my university, I had the privilege of organizing numerous events and workshops focused on global business practices, cultural awareness, and networking opportunities with industry professionals. These experiences have not only enriched my knowledge but have also fostered my passion for international marketing and cross-cultural collaboration.Upon graduation, I aspire to contribute my skills, knowledge, and enthusiasm to a reputable organization like Acme Corporation. I am confident that my academic background, practical experience, and unwavering commitment to excellence would make me a valuable asset to your international marketing team.I would welcome the opportunity to discuss my qualifications and potential contributions in greater detail. Please find my resume enclosed for your consideration. Thank you for your time, and I look forward to hearing from you.Sincerely,Samantha RobertsonEnclosure: Resume。

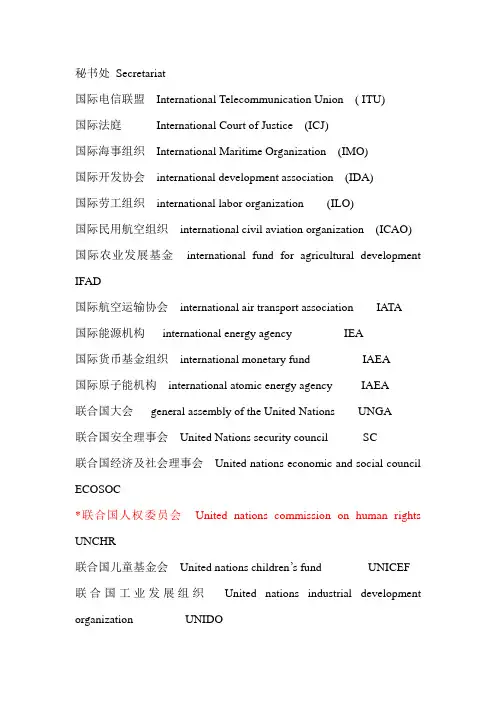

翻译硕士(MTI)国际组织简写\现在所有的相关大的国际组织都用的是简写,一是为了简便二来对考翻译硕士(MTI)的我们也一样有好处(不用写那么多单词啦),下面是我总结的翻译硕士(MTI)国际组织简写,方便大家记忆的。

欧盟European Union -- EU 欧元(euro)阿盟阿拉伯国家联盟League of Arab States -- LAS非洲联盟(African Union -- AU,简称“非盟”)东南亚国家联盟(简称东盟,Association of Southeast Asian Nations -- ASEAN北大西洋公约组织(North Atlantic Treaty Organization -- NA TO ),简称北约1949年4月4日,美国、加拿大、英国、法国、比利时、荷兰、卢森堡、丹麦、挪威、冰岛、葡萄牙和意大利等12国在美国首都华盛顿签订了北大西洋公约,宣布成立北大西洋公约组织(North Atlantic Treaty Organization -- NATO ),简称北约。

大赦国际(Amnesty International -- AI)英联邦(The Commonwealth)不结盟运动(Non-Aligned Movement -- NAM)巴黎俱乐部(Paris Club) 也称“十国集团”(Group-10)南方中心(South Centre) 是以促进南南合作为宗旨的国际著名政府间组织和智库,其前身是南方委员会。

南方委员会为第三世界国家政界、外交界、经济界和学术界著名人士组成的国际性组织。

1985年由委内瑞拉前总统佩雷斯建议,1986年5月在吉隆坡第二次南南会议决定建立,同年9月宣布正式成立,1994年9月正式改名为南方中心。

总部设在日内瓦,现有包括中国在内的51个成员。

独联体是独立国家联合体(Commonwealth of Independent States -- CIS) 的简称上海合作组织(Shanghai Cooperation Organization -- SCO)阿拉伯各国议会联盟(Arab Inter-Parliamentary Union -- AIPU)阿拉伯国家联盟(League of Arab States -- LAS,简称“阿盟”)西欧联盟(Western European Union -- WEU) 1955年5月6日成立,前身为布鲁塞尔条约组织,拥有比利时、法国、德国、希腊、意大利、卢森堡、荷兰、葡萄牙、西班牙和英国10个正式成员国。

常见国际英文缩写词汇常见国际组织英文缩写UN ( United Ntions) 联合国UNSC(Security Council)联合国安全理事会FO (Food nd griculture Orgniztion of the United Ntions) (联合国)粮食及农业组织UNESCO (United Ntions Eductionl, Scientific nd Culturl Orgniztion) 联合国教科文组织UNCF (United Ntions Children's Fund,其前身是United Ntions Interntionl Children's Emergency Fund) 联合国儿童基金会UNIDO (United Ntions Industril Development Orgniztion)联合国工业进展组织UNDP (United Ntions Development Progrmme)联合国开发计划署UNEP (United Ntions Environment Progrmme)联合国环境署UNCDF(United Ntions Cpitl Development Fund)联合国资本开发基金会UNCTD (United Ntions Conference on Trde nd Development) 联合国贸易与进展会议WHO (World Helth Orgniztion) 世界卫生组织WMO (World Meteorologicl Orgniztion) 世界气象组织WTO (World Trde Orgniztion) 世界贸易组织GTT (Generl greement on Triffs nd Trde) 关税及贸易组织WIPO (World Intellectul Property Orgniztion)世界知识产权组织WPC (World Pece Council) 世界和平理事会ILO (Interntionl Lbour Orgniztion) 国际劳工组织IMF (Interntionl Monetry Fund) 国际货币基金组织IOC (Interntionl Olympic Committee) 国际奥林匹克委员会UPU (Universl Postl Union) 万国邮政联盟ITU (Interntionl Telecommuniction Union) 国际电信联盟IFC(Interntionl Finnce Corportion) 国际金融公司IMO (Interntionl Mritime Orgniztion) 国际海事组织ISO (Interntionl Stndrd Orgniztion) 国际标准化组织ICO (Interntionl Civil vition Orgniztion) 国际民用航空组织ID (Interntionl Development ssocition) 国际开发协会IFD (Interntionl Fund for griculturl Development) 国际农业进展基金会IOJ (Interntionl Orgniztion of Journlists) 国际新闻工协会ICC(Interntionl Chmber of Commerce)国际商会UE(Universl Espernto ssocition)国际世界语协会INTELST (Interntionl telecommunictions Stellitic)国际通信卫星机构IRTO (Interntionl Rdio nd Television Orgniztion)国际广播电视组织IE (Interntionl tomic Energy gency) 国际原子能机构NTO (North tlntic Trety Orgniztion)北大西洋公约组织OPEC(Orgniztion of Petroleum Exporting Countries) 石油输出国组织OECD (Orgniztion for Economic Coopertion nd Development)经济合作与进展组织CME(Council for Mutul Economic ssistnce)经济互助委员会(经互会)PEC (si nd Pcific Economic Coopertion) 亚洲太平洋经济合作组织SEN (ssocition of Southest sin Ntions)东南亚GJ联盟OU (Orgniztion of fricn Unity) 非洲统一组织OIC (Orgniztion of the Islmic Conference) 伊斯兰会议组织CIS (Commonwelth of Independent Sttes) 独立GJ联合体EU (Europen Union) 欧洲联盟IPU (Inter-Prlimentry Union) 各国议会联盟OSCE (Orgniztion for Security nd Coopertion in Europe)欧洲安全与合作组织EEC (Europen Economic Communities) 欧洲经济共同体OEEC (Orgniztion for Europen Economic Coopertion)欧洲经济合作组织NM (the Non-ligned Movement) 不结盟运动NC (fricn Ntionl Congress) 非洲RM大会PLO (Plestine Libertion Orgniztion)XX勒斯坦解放组织ICRC (Interntionl Committee of the Red Cross) 红十字国际委员会NS(Ntionl eronutics nd Spce dministrtion)美国航天太空总署。