Reference Architecture Representation Environment (RARE) - A Reference Architecture Archive

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:223.52 KB

- 文档页数:13

建筑方案图纸英文Architectural DrawingArchitectural drawing is a crucial component of the design process in the field of architecture. It serves as a visual representation of a proposed building or structure, providing detailed information about its layout, dimensions, materials, and specifications. These drawings are essential for communication between architects, engineers, clients, and construction teams. In this article, we will explore the different types of architectural drawings, their purposes, and the importance of accurate and precise drawings in the construction industry.One of the most common types of architectural drawings is the floor plan. This drawing shows the layout of each floor of a building, including the location of walls, doors, and windows. It provides a clear understanding of the flow and organization of spaces. Floor plans are instrumental in determining the functionality and efficiency of a building, as well as the circulation of people within it. They are also used by interior designers to plan the placement of furniture and fixtures.Another type of architectural drawing is the elevation. Elevation drawings show the exterior views of a building from different angles. They provide a detailed depiction of the building's facade, depicting the design and arrangement of windows, doors, and other exterior elements. Elevation drawings help in assessing the aesthetic aspect of a building and its integration into the surrounding environment. It is especially crucial in urban planning and architectural visualization.Sections are drawings that cut through a building vertically or horizontally, showing the internal elements and structure. These drawings provide a cross-sectional view of the building, allowing architects and engineers to understand the building's interior spatial arrangement, structural elements, and services. Sections are vital in ensuring the coordination of various building systems, such as electrical, plumbing, and HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) systems.In addition to these, architectural drawings may also include details such as construction sections, site plans, and electrical and plumbing layouts. Construction sections show specific details of construction assemblies, such as wall sections, roof details, and floor constructions. Site plans provide an overview of the building's location and its relationship with the surroundings, including roads, landscaping, and utilities. Electrical and plumbing layouts illustrate the placement and routing of electrical wires, outlets, plumbing pipes, and fixtures within the building. Accuracy and precision are of utmost importance in architectural drawings. Any errors or inconsistencies can result in costly construction mistakes and delays. Architectural drawings need to be clear, concise, and easy to understand, using standardized symbols, scales, and notations. It is crucial for architects to pay attention to every detail, from the dimensions of the rooms to the materials and finishes specified. Similarly, engineers need to accurately depict the structural elements and ensure their compatibility with the architectural design.The advent of computer-aided design (CAD) has revolutionized architectural drawing. CAD software allows architects and engineers to create accurate and detailed drawings, providing the flexibility to make changes and revisions easily. It also enables the generation of 3D models and renderings, facilitating better visualization and understanding of the proposed design. With CAD, drawings can be easily shared and transmitted digitally, enhancing communication and collaboration among project stakeholders.In conclusion, architectural drawing is an indispensable tool in the design and construction process. It enables architects, engineers, clients, and construction teams to communicate and visualize a building's design and specifications accurately. The different types of drawings, such as floor plans, elevations, and sections, provide essential information about the building's layout, structure, and aesthetic qualities. Accuracy and precision are vital in ensuring the successful execution of architectural drawings, and CAD technology has greatly improved the efficiency and effectivenessof the drawing process.。

立体主义艺术英语介绍作文Cubism, a groundbreaking art movement that emerged in the early 20th century, revolutionized the way we perceive and depict reality. Spearheaded by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, Cubism challenged traditional artistic conventions by presenting subjects from multiple perspectives simultaneously. This avant-garde movement sought to deconstruct forms and reconstruct them into geometric shapes, thereby fracturing the conventional notions of space and time in art.At its core, Cubism aimed to capture the essence of the subject rather than its literal representation. Artists employed a variety of techniques such as fragmentation, overlapping, and geometric simplification to achieve this goal. By breaking down objects into basic geometric forms like cubes, spheres, and cones, Cubist painters aimed to represent the subject from various viewpoints simultaneously. This multiplicity of perspectives allowed viewers to engage with the artwork in a more dynamic andinteractive manner, inviting them to explore different facets of reality.One of the key characteristics of Cubism is its emphasis on the two-dimensional surface of the canvas. Rather than creating illusionistic depth, Cubist artists flattened the pictorial space, foregrounding the surface as the primary site of artistic expression. This departure from traditional perspective challenged viewers to reconsider their relationship with the artwork and encouraged them to engage with it on a more intellectual level.Furthermore, Cubism was not limited to painting alone; it also extended to sculpture and collage. Sculptors such as Jacques Lipchitz and Alexander Archipenko embraced the principles of Cubism, translating them into three-dimensional form. Through the use of fragmented planes and abstracted shapes, Cubist sculptures captured the essence of the subject in a manner that was both innovative and unconventional.The influence of Cubism extended far beyond the confines of the art world, permeating into otherdisciplines such as literature, architecture, and design. Writers such as Gertrude Stein and poets like Guillaume Apollinaire were inspired by the fragmented aesthetics of Cubism, incorporating its principles into their literary works. Similarly, architects such as Le Corbusier drew upon Cubist ideas in their designs, advocating for a more rational and geometric approach to architecture.In conclusion, Cubism remains one of the most significant art movements of the 20th century, challenging traditional notions of representation and paving the wayfor modern abstraction. Through its innovative techniques and radical approach to form, Cubism continues to inspire artists and audiences alike, reminding us of the transformative power of art to reshape our perceptions of the world.。

建筑文化英语Architecture is not only a form of art, but also a representation of culture. It reflects the traditions, beliefs, and values of a society. As a result, architecture plays a crucial role in shaping and preserving cultural identity. In this article, we will explore the significance of architectural culture and its impact on society.Firstly, architectural culture embodies a society's historical background. By studying architectural designs and structures, we can gain insights into the past. Ancient civilizations, such as the Egyptians and Greeks, left behind monumental structures like the pyramids and the Parthenon, which are not only architectural marvels but also windows into their cultures.For instance, the pyramids of Egypt symbolize the importance of the afterlife and the divine power of the pharaohs. The intricately carved columns of the Parthenon demonstrate the admiration and reverence the ancient Greeks had for their gods and goddesses. Overall, architectural culture provides a tangible link to the past, allowing us to understand and appreciate the traditions that have shaped our present.Moreover, architectural culture influences the way we perceive and interact with our surroundings. The design of buildings and urban spaces can greatly impact human behavior and well-being. For instance, cities in Europe often feature narrow streets, vibrant plazas, and buildings with intricate facades, creating a sense of intimacy and community. In contrast, modern cities often prioritize functionality over aesthetics, leading to a more impersonal and disconnected urban environment.Architectural culture also shapes our perception of beauty. Different cultures have distinct architectural styles that reflect their unique aesthetics. For example, traditional Chinese architecture is characterized by its emphasis on harmony with nature, symmetrical designs, and intricate decorations. On the other hand, Islamic architecture is known for its geometric patterns, intricate tile work, and dome structures. The beauty of these architectural styles lies in their ability to blend functionality with artistic expression.Furthermore, architectural culture contributes to the preservation and conservation of heritage sites. Historical buildings and landmarks are a testament to a society's history, and they bring a sense of pride and identity. Cultural heritage sites like the Taj Mahal in India or the Great Wall of China attract tourists from around the world, generating economic benefits and promoting cultural exchange. It is imperative to preserve and safeguard these sites to ensure they remain accessible to future generations.In conclusion, architectural culture is an integral part of our global heritage. It acts as a bridge between the past and the present, providing insights into the traditions and values of different societies. Furthermore, architectural culture shapes our perceptions, influences our behavior, and contributes to the preservation of cultural heritage. By embracing and celebrating architectural diversity, we can foster a better understanding and appreciation of our shared humanity.。

The Differences Between Eastern And Western Architecture姓名:张欣(1010641124)卢雅静(1010641128)石姗姗(1010641132)班级:10建筑学1班指导老师:唐咏梅The Differences Between Eastern And Western ArchitectureThe representation nations of eastern architecture are China,India and Japan. While those of western are Greece and Rome.The biggest difference between eastern and western architecture is that the east highlights the natural landscape while the west highlights the buildings.1.The the materials of architectureThe east: mainly wood and earthThe west: Mainly stone2.The layout of architectureThe east: the majority emphasize the entiretyThe west: attach importance to the individual building3.About the theme of the culture of architectureThe east: focus on advocating the imperial power and etiquetteThe west: focus on publicising their majestic God and showing their admiration and respect4.About the style of the artThe east: depend on the harmony between nature and humanThe west: highlight the conflicting beauty between nature andhuman. The wide and close inner space of the religious building lets people bring out the religious passion and craziness.5.The difference of the constructionThe east: woodwork, mainly post and lintel constructionThe west: by piling up the stones,their walls are thicker, the openings in the wall are smaller and the inner space is closer.。

建筑物的英语作文Architecture is an art form that has been practiced for centuries. From the ancient wonders of the world to the modern skyscrapers that dominate our cities, architecture has played a crucial role in shaping the world around us.In this essay, we will explore the significance of architecture, its impact on society, and the role it playsin our lives.First and foremost, architecture is a reflection of a society's culture and values. The buildings and structures that we create are a physical representation of our beliefs, aspirations, and achievements. For example, the grand cathedrals of Europe are a testament to the religious devotion of the people who built them, while the towering skyscrapers of New York City symbolize the ambition and innovation of American society. In this way, architecture serves as a mirror of our collective identity, allowing usto express ourselves and communicate our values to future generations.Moreover, architecture has a profound impact on ourdaily lives. The spaces that we inhabit, whether it's our homes, workplaces, or public spaces, have a directinfluence on our well-being and quality of life.Thoughtfully designed buildings can enhance our productivity, foster a sense of community, and promote a healthy lifestyle. On the other hand, poorly designed or neglected spaces can have a negative impact on our mental and physical health. Therefore, it is essential for architects and urban planners to consider the human experience when creating new environments, ensuring that they are not only aesthetically pleasing but alsofunctional and conducive to our well-being.Furthermore, architecture plays a crucial role in addressing some of the most pressing challenges of our time, such as climate change and urbanization. Sustainable architecture, which focuses on minimizing the environmental impact of buildings and maximizing their energy efficiency, has become increasingly important in the face of global warming. By incorporating green technologies, renewablematerials, and innovative design strategies, architects are able to create buildings that are not only environmentally friendly but also resilient to the effects of climate change. Additionally, as more people move to cities, architects are tasked with designing urban spaces that are efficient, inclusive, and adaptable to the needs of a diverse population. This requires a holistic approach that takes into account factors such as transportation, housing, and public amenities, in order to create cities that are both livable and sustainable for future generations.In conclusion, architecture is a powerful form of expression that shapes our world in profound ways. It reflects our culture, influences our daily lives, and addresses the challenges of our time. As we continue to evolve and face new challenges, it is essential that we recognize the significance of architecture and the role it plays in creating a better future for all. By embracing innovative design, sustainable practices, and a commitment to the well-being of society, we can ensure that the buildings and spaces we create will continue to inspire and enrich our lives for generations to come.。

美术英语work 作品work of art 艺术作品masterpiece 杰作plastic arts 造型艺术graphic arts 形象艺术Fine Arts 美术art gallery 画廊,美术馆salon 沙龙exhibition 展览collection 收藏author 作者style 风inspiration 灵感,启发muse 灵感purism 修辞癖conceptism格言派,警名派Byzantine 拜占庭式Romanesaue罗马式Gothic 哥特式Baroque 巴洛克式Rococo 洛可可式classicism 古典主义,古典风格neoclassicism 新古典主义romanticism 浪漫主义realism 现实主义symbolism 象征主义impressionism 印象主义Art Nouveau 新艺术主义expressionism 表现主义Fauvism 野兽派abstract art 抽象派, 抽象主义Cubism 立体派, 立体主义Dadaism 达达主义surrealism 超现实主义naturalism 自然主义existentialism 存在主义futurism 未来主义abstract art:抽象派艺术●A nonrepresentational style that emphasizes formal values over the representation of subject matter.强调形式至上,忽视内容的一种非写实主义绘画风格。

★Kandinsky produced abstract art characterized by imagery that had a musicical quality.**斯基创作的抽象派作品有一种音乐美。

abstract expressionism:抽象表现派,抽象表现主义=●A nonrepresentational style that emphasizes emotion,strongcolor,and giving primacy to the art of painting.把绘画本身作为目的,以表达情感和浓抹重涂为特点的非写实主义风格。

Standards facilitate the Fourth Industrial Revolution 专访德国电气电子信息技术委员会(DKE)总裁迈克尔·泰格勒Interview with Mr. Michael Teigeler, Managing Director of German Commission Electrical and Electronic Information Technology in DIN andVDE (DKE)标准助推第四次工业革命BETTER COMMUNICATION | GREATER VALUEIndustry 4.0 represents the Fourth Industrial Revolution. What is Industry 4.0 in your opinion? What is German standardization strategy in this process?Mr. Michael Teigeler: The fourth industrial revolution will affect the whole eco-system of the manufacturing industry. The previous industrial revolutions changed the way how products have been produced in a vertical dimension, with other aspects remained more or less unchanged. In the fourth industrial revolution, we will see an extended value chain connecting smart factories, smart products and smart services. These three dimensions form the three axis of the Reference Architecture Model “Industrie 4.0” (RAMI 4.0), a model which has been introduced by German experts and will guide the standardization work worldwide.The central building blocks of this process are seamless data structures. For example, the concept of “Digital Twin” foresees a complete digital representation of a product or system throughout its entire life cycle. This digital representation monitors in real time key requirements on interoperability, safety and security are conform to standards, which can be tested virtually. New services can also be created to extend the values of standardization and better serve industry and consumer needs.You said that the Standardization Council Industry 4.0 is the linchpin of the process in your presentation at the international symposium on standardization strategies held in Beijing in November 2018. Could you tell us a little more about it?The concept of “Industrie 4.0” covers many areas which have been treated in silos in the past, also for standardization work. Today, standardization activities need to be coordinated to interlink different aspects across functions and sectors. Therefore the Standardization Council “Industrie 4.0” was established. There are several key tasks. First, there is a need to initiate and coordinate the development of digital production standards at national and international level. This requires liaising with industry and standardization bodies, i.e. to coordinate the needs between the stakeholders represented through the German “Industrie 4.0” platform and the various standards developing organizations (SDOs). Second, the Standardization Council “Industrie 4.0” aims to facilitate the creation of international standards through, for example, partnering with ISO and IEC, and through regular technical discussion in the Sino-German standardization cooperation commission and the established Sub Working Group Smart Manufacturing/Industry 4.0.Moreover, the SCI 4.0 collaborates with pilot projects, which enables quick and tailored standardization activities utilizing the findings of these initiatives.Finally the Standardization Council “Industrie 4.0” coordinates the draft of Standardization Roadmap “Industrie 4.0”.The German Standardization Roadmap Industrie 4.0, released by DIN, DKE and VDE, is the most dowloaded document in the online library and highly interested by China. Could you introduce more about it? What benefits can it bring to industries and consumers across the globe?Standardization roadmaps address several targets. First of all they give an overview on the current standardization landscape. This includes the different players like standardization organizations and technical committees but also the different existing standards and ongoing standardization projects. Secondly the roadmap identifies needs for new standards based on a gap analysis. Recommendations for standardization work are derived based on this step. Altogether the roadmap describes the German standardization strategies to achieve “Industrie 4.0”. The roadmap is not a static document. It is written by a large number of technical experts from various disciplines and it is updated bi-annually.DKE is a trusted platform for standardization, cooperation and interaction of experts in the areas of electrical engineering, electronics and information technologies. How does DKE encourage SMEs to access standards and participate in standardization?BETTER COMMUNICATION | GREATER VALUEFirst of all, DKE provides a level playing field for all technical experts regardless they are from a global enterprise or a SME. The participation in DKEs work is free of charge which is another benefit especially for SMEs.Additionally DKE offers free trainings to technical experts, including those from SMEs. We are as well offering a tailored program to ease the access to standards for SMEs, a help desk to support experts particularly from SMEs in participation in standardization activities, as well as tools to guide the use of standards.Reciprocally, SMEs also see the benefit by being active in drafting new standards.What benefits can SMEs receive in the participation in standardization?Typically SMEs have excellent know how about a specific technology. But due to their size they cannot cover all technical aspects of “Industrie 4.0”. Through participation in standardization, companies can make sure that their specific technology is recognized and forms part of a standard. In other words even SMEs can influence the wording of requirements in a standard in a way which supports the application of their specific technology.Another benefit is to sense technical trends through participation in standardization. For example if a new safety concept is adopted in a safety standard you can adapt the market introduction of new products to the foreseeable introduction of such a standard. As a consequence we see many ofthe German “hidden champion” SMEs in our technical committees.。

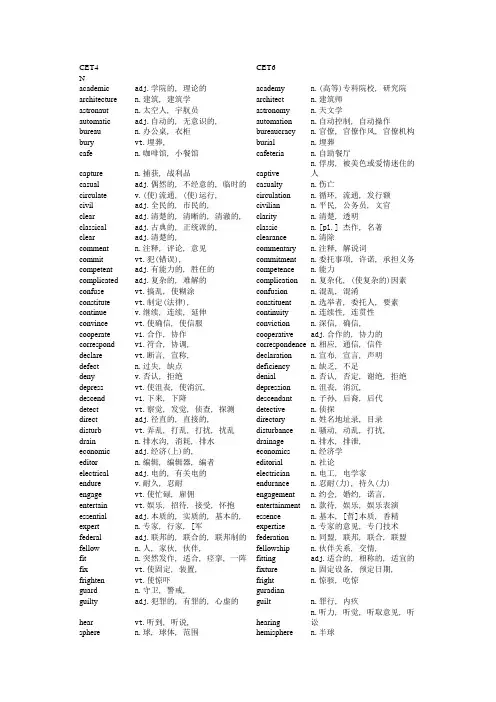

CET4CET6Nacademic adj.学院的, 理论的academy n.(高等)专科院校, 研究院architecture n.建筑, 建筑学architect n.建筑师astronaut n.太空人, 宇航员astronomy n.天文学automatic adj.自动的, 无意识的, automation n.自动控制, 自动操作bureau n.办公桌, 衣柜bureaucracy n.官僚, 官僚作风, 官僚机构bury vt.埋葬,burial n.埋葬cafe n.咖啡馆, 小餐馆cafeteria n.自助餐厅capture n.捕获, 战利品captive n.俘虏, 被美色或爱情迷住的人casual adj.偶然的, 不经意的, 临时的casualty n.伤亡circulate v.(使)流通, (使)运行, circulation n.循环, 流通, 发行额civil adj.全民的, 市民的, civilian n.平民, 公务员, 文官clear adj.清楚的, 清晰的, 清澈的, clarity n.清楚, 透明classical adj.古典的, 正统派的,classic n.[pl.] 杰作, 名著clear adj.清楚的, clearance n.清除comment n.注释, 评论, 意见commentary n.注释, 解说词commit vt.犯(错误), commitment n.委托事项, 许诺, 承担义务competent adj.有能力的, 胜任的competence n.能力complicated adj.复杂的, 难解的complication n.复杂化, (使复杂的)因素confuse vt.搞乱, 使糊涂confusion n.混乱, 混淆constitute vt.制定(法律), constituent n.选举者, 委托人, 要素continue v.继续, 连续, 延伸continuity n.连续性, 连贯性convince vt.使确信, 使信服conviction n.深信, 确信,cooperate vi.合作, 协作cooperative adj.合作的, 协力的correspond vi.符合, 协调, correspondence n.相应, 通信, 信件declare vt.断言, 宣称,declaration n.宣布, 宣言, 声明defect n.过失, 缺点deficiency n.缺乏, 不足deny v.否认, 拒绝denial n.否认, 否定, 谢绝, 拒绝depress vt.使沮丧, 使消沉,depression n.沮丧, 消沉,descend vi.下来, 下降descendant n.子孙, 后裔, 后代detect vt.察觉, 发觉, 侦查, 探测detective n.侦探direct adj.径直的, 直接的, directory n.姓名地址录, 目录disturb vt.弄乱, 打乱, 打扰, 扰乱disturbance n.骚动, 动乱, 打扰,drain n.排水沟, 消耗, 排水drainage n.排水, 排泄,economic adj.经济(上)的, economics n.经济学editor n.编辑, 编辑器, 编者editorial n.社论electrical adj.电的, 有关电的electrician n.电工, 电学家endure v.耐久, 忍耐endurance n.忍耐(力), 持久(力) engage vt.使忙碌, 雇佣engagement n.约会, 婚约, 诺言, entertain vt.娱乐, 招待, 接受, 怀抱entertainment n.款待, 娱乐, 娱乐表演essential adj.本质的, 实质的, 基本的, essence n.基本, [哲]本质, 香精expert n.专家, 行家, [军expertise n.专家的意见, 专门技术federal adj.联邦的, 联合的, 联邦制的federation n.同盟, 联邦, 联合, 联盟fellow n.人, 家伙, 伙伴, fellowship n.伙伴关系, 交情,fit n.突然发作, 适合, 痉挛, 一阵fitting adj.适合的, 相称的, 适宜的fix vt.使固定, 装置, fixture n.固定设备, 预定日期, frighten vt.使惊吓fright n.惊骇, 吃惊guard n.守卫, 警戒,guradianguilty adj.犯罪的, 有罪的, 心虚的guilt n.罪行, 内疚hear vt.听到, 听说, hearing n.听力, 听觉, 听取意见, 听讼sphere n.球, 球体, 范围hemisphere n.半球history n.历史, 历史学, historian n.历史学家, 史家host n.主机,主人,旅馆招待hostess n.女主人, 女房东,human n.人, 人类humanity n.人性, 人类, 博爱, 仁慈ignorant adj.无知的ignorance n.无知, 不知imitate vt.模仿, 仿效, 仿制, 仿造imitation n.模仿, 效法, 冒充,incident n.事件, 事变incidence n.落下的方式, 影响范围,infer v.推断inference n.推论initial adj.最初的, 词首的, 初始的initiative n.主动sight n.视力, 视觉, 见, 瞥见, insight n.洞察力, 见识inspire vt.吸(气), 鼓舞, 感动, 激发, inspiration n.灵感instal installment n.部分intellectual adj.智力的, 有智力的, 显示智力的intellect n.智力journal n.定期刊物, 杂志, 航海日记, journalist n.新闻记者, 从事新闻杂志业的人legal adj.法律的, 法定的, 合法legislation n.立法, 法律的制定(或通过) liable adj.有责任的, 有义务的, liability n.责任, 义务, 倾向likely adj.很可能的, 合适的, likelihood n.可能, 可能性line n.绳, 索, 线路, 航线, 诗句liner n.<美>班机, 划线者, 衬垫literary adj.文学(上)的, 从事写作的, literacy n.有文化,有教养,有读写能力local adj.地方的, 当地的, locality n.位置, 地点lodge n.门房, (猎人住的)山林小屋,lodging n.寄宿处, 寄宿,mechanics n.(用作单数)机械学、力学, mechanism n.机械装置, 机构, 机制member n.成员, 会员, 议员, membership n.成员资格, 成员人数message n.消息, 通讯, messenger n.报信者, 使者miserable adj.痛苦的, 悲惨的, 可怜misery n.痛苦, 苦恼,moral adj.道德(上)的, 精神的morality adj.道德的night n.夜, 夜晚, 黑暗, 死亡nightmare n.梦魇, 恶梦, 可怕的事物normal n.正规, 常态, [数学]法线norm n.标准, 规范note n.笔记, 短信,notation n.符号novel n.小说, 长篇故事novelty n.新颖, 新奇,oblige vt.迫使, 责成obligation n.义务, 职责, 债务offend v.犯罪, 冒犯, 违反, offence n.犯罪, 冒犯,optimistic adj.乐观的optimism n.乐观, 乐观主义optional adj.可选择的, 随意的option n.选项,part n.部分, 局部, 零件, 角色partition n.分割,participate vi.参与, 参加, 分享, 分担participant n.参与者, 共享者perceive v.感知, 感到, 认识到perception n.理解perfect adj.完美的, perfection n.尽善尽美, 完美, 完成period n.时期, 学时, 节, periodical adj.周期的, 定期的personal adj.私人的, personality n.个性, 人格, 人物, persuade v.说服, 劝说, (使)相信, persuasion n.说服, 说服力photograph n.照片photography n.摄影, 摄影术pray v.祈祷, 恳求, 请prayer n.祈祷prescribe v.指示, 规定, 处(方), 开(药)prescription n.指示, 规定,present n.赠品, 礼物, 现在, 瞄准presentation n.介绍, 陈述, 赠送, 表达prior adj.优先的, 在前的priority n.先, 前, 优先, 优先权private adj.私人的, 私有的privacy n.独处而不受干扰, 秘密proceed vi.进行, 继续下去, 发生proceeding n.行动, 进行,product n.产品, 产物, 乘积productivity n.生产力project n.计划, 方案,projector n.放映机propose vt.计划, 建议, proposition n.主张, 建议, 陈述, 命题type n.类型, 典型, 模范, prototype n.原型psychological adj.心理(上)的psychology n.心理学, 心理状态public n.公众, (特定的)人群, 公共场所publicity n.公开pure adj.纯的, 纯粹的, 象的purity n.纯净, 纯洁, 纯度pursue vt.追赶, 追踪, pursuit n.追击qualify v.(使)具有资格, qualification n.资格, 条件,quarter n.四分之一, quarterly adj.一年四次的, 每季的question n.问题, 疑问, 询问questionnaire n.调查表, 问卷rate n.比率, 速度,rating n.等级级别(尤指军阶), 额定, rebel n.造反者rebellion n.谋反receive vt.收到, 接到,recipient adj.容易接受的, 感受性强的refresh v.(使)精神振作, refreshment n.(常pl.) 点心, 饮料,rely v.依赖, 依靠, reliance n.信任, 信心,remain vi.保持, 逗留, 剩余, 残存remainder n.残余, 剩余物,replace vt.取代, 替换, 代替, replacement n.归还, 复位,represent vt.表现, 描绘, 声称, representation n.表示法,resemble vt.象, 类似resemblance n.类同之处reserve vt.储备, 保存reservation n.保留, (旅馆房间等)预定, 预约retain vt.保持, 保留retention 保持力reveal vt.展现, 显示, 揭示, 暴露revelation n.显示,romantic adj.传奇式的, 浪漫的, romance n.冒险故事, 浪漫史,royal adj.王室的, 皇家的,royalty n.皇室, 王权senate n.参议院, 上院senator n.参议员,sense n.官能, 感觉, 判断力,sensation n.感觉, 感情, 感动, 耸人听闻的ship n.船, 海船, 舰shipment n.装船, 出货society n.社会, ...会, ...社,流社会sociology n.社会学solid n.固体, 立体solidarity n.团结special n.特派员, 专车, 专刊speciality n.特性, 特质, 专业, 特殊性specific n.特效药, 细节specification n.详述, [常 pl.] 规格, 说明书statistical adj.统计的, 统计学的statistics n.统计学, 统计表stimulate vt.刺激, 激励stimulus n.刺激物, 促进因素,succession n.连续, 继承, 继任, 演替successor n.继承者, 接任者, 后续的事物superior n.长者, 高手, 上级superiority n.优越, 高傲surgery n.外科, 外科学surgeon n.外科医生survive v.幸免于, 幸存, 生还survival n.生存, 幸存, 残存,suspend vt.吊, 悬挂suspension n.吊, 悬浮, 悬浮液,synthetic adj.合成的, 人造的, 综合的synthesis n.综合, 合成test n.测试, 试验, 检验testimony n.证词(尤指在法庭所作的),thief n.小偷, 贼theft n.偷, 行窃, 偷窃的事例thirsty adj.口渴的, 渴望的, 热望的thirst n.渴, 口渴, (~ for)渴望, 热望valid adj.[律]有效的, 有根据的, validity n.有效性, 合法性, 正确性vegetable n.蔬菜, 植物, 生活呆板单调的人vegetation n.[植]植被, (总称)植物、voluntary adj.自动的, 自愿的, volunteer n.志愿者, 志愿兵war n.战争warfare n.战争, 作战, 冲突, 竞争young adj.年轻的, 年纪小的, youngster n.年青人, 少年Vaccommodate vt.供应, 供给, 使适应, accommodation n.住处, 膳宿, (车, 船, 飞机等的)预accordance n.一致, 和谐accord n.一致, 符合, 调和, 协定acquaintance n.相识, 熟人acquaint vt.使熟知, 通知active adj.积极的, 能起作用的, activate vt.刺激, 使活动join vi.参加, 结合, 加入adjoin v.邻接, 毗连administration n.管理, 经营, 行政部门administer v.管理, 给予, 执行advertisement n.广告, 做广告advertise v.做广告, 登广告firm n.公司, (合伙)商号affirm v.断言, 确认, 肯定authority n.权威, 威信, 权威人士, 权力,authorize v.批准available adj.可用到的, 可利用的, avail vi.有益于, 有帮助, 有用, 有利characterise vt.表现...的特色, 刻画的...性格character n.(事物的)特性, 性质, 特征(的总和commemorate vt.纪念collision n.碰撞, 冲突collide vi.碰撞, 抵触comprehension n.理解, 包含comprehend vt.领会, 理解, 包括(包含), 由...组成conservation n.保存, 保持, 守恒conserve vt.保存, 保藏contradiction n.反驳, 矛盾contradict vt.同...矛盾, 同...抵触relate vt.叙述, 讲, 使联系, 发生关系correlate vt.使相互关联different adj.不同的differentiate v.区别, 区分dinner n.正餐, 宴会dine vi.吃饭, 进餐light n.光, 日光, 发光体, 灯enlighten vt.启发, 启蒙, 教导,elevator n.电梯, 升降机, [空]升降舵elevate vt.举起, 提拔,rich adj.富的, 有钱的, 富有的, enrich vt.使富足, 使肥沃, 装饰, vision n.视力, 视觉, 先见之明, envisage v.正视fabric n.织品, 织物, 布, fabricate vt.制作, 构成, 捏造,facility n.容易, 简易, 灵巧,facilitate vt.(不以人作主语的)使容易, formula n.公式, 规则, 客套语formulate vt.用公式表示, 明确地表达, general n.普通, 将军, 概要generalize vt.归纳, 概括, 推广, 普及haste n.匆忙, 急忙hasten v.催促, 赶紧, 促进, 加速height n.高度, 海拔, 高地(常用复数)heighten v.提高, 升高prison n.监狱imprison vt.监禁, 关押inhabitant n.居民, 居住者inhabit vt.居住于, 存在于, 占据, 栖息initial adj.最初的, 词首的, 初始的initiate vt.开始, 发动, 传授injection n.注射, 注射剂, inject vt.注射, 注入intense adj.强烈的, 剧烈的, intensify vt.加强act n.幕, 法案, 法令, 动作, interact vi.互相作用, 互相影响connect v.连接, 联合, 关连interconnect vt.使互相连接length n.长度, 长, 时间的长短, [语]音长lengthen v.延长, (使)变长less n.较少, 较小lessen v.减少, 减轻minimum adj.最小的, 最低的minimize vt.将...减到最少mobile adj.可移动的, 易变的, 机动的mobilize v.动员necessity n.必要性, 需要, (常 pl.) 必需品necessitate v.成为必要name n.名字, 名称, 姓名, 名誉nominate vt.提名, 推荐, 任命, 命名note n.笔记, 短信,notify v.通报origin n.起源, 由来, 起因, originate vt.引起, 发明, 发起, 创办portrait n.肖像, 人像portray v.描绘preceding adj.在前的, 前述的precede v.领先(于), 在...之前, 先于pure adj.纯的, 纯粹的, 纯净的,purify vt.使纯净claim n.(根据权利提出)要求, 要求权,proclaim vt.宣布, 声明, 显示, 显露quantity n.量, 数量quantify vt.确定数量radiation n.发散, 发光, 发热,radiate vt.放射, 辐射, 传播, 广播pay n.薪水, 工资repay v.偿还, 报答, 报复residence n.居住, 住处reside vi.居住rotten adj.腐烂的, 恶臭的,rot v.(使)腐烂, (使)腐败significance n.意义, 重要性signify vt.表示, 意味spark n.火花, 火星, sparkle v.发火花, (使)闪耀, ( sufficient adj.充分的, 足够的suffice vi.足够, 有能力pass n.经过, 关口, 途径,surpass vt.超越, 胜过terminal n.终点站, 终端, 接线端terminate v.停止, 结束, 终止terrible adj.很糟的, 极坏的,terrify vt.使恐怖, 恐吓plant n.植物, 庄稼, 工厂, 车间, 设备transplant v.移植, 移种, 移民, 迁移unity n.团结, 联合, 统一, 一致unify vt.统一, 使成一体visual adj.看的, 视觉的, visualize vt.形象, 形象化, 想象adjambition n.野心, 雄心ambitious adj.有雄心的, 野心勃勃的analysis n.分析, 分解analytic adj.分析的, 解析的appreciate vt.赏识, 鉴赏, 感激appreciable adj.可感知的, 可评估的authority n.权威, 威信, authoritative adj.权威的, 有权威的, 命令的colony n.殖民地, 侨民, colonial adj.殖民的, 殖民地的 compare v.比较, 相比, 比喻 n.比较comparable adj.可比较的, 比得上的compete vi.比赛, 竞争competitive adj.竞争的compose v.组成, 写作, 排字,composite adj.合成的, 复合的confident adj.自信的, 确信的confidential adj.秘密的, 机密的consequence n.结果, [逻]推理, 推论,consequent adj.作为结果的, 随之发生的corporation n.[律]社团, 法人, 公司, corporate adj.社团的, 法人的,custom n.习惯, 风俗, <动词单用>海关, customary adj.习惯的, 惯例的dead adj.死的, 无感觉的, deadly adj.致命的, 势不两立的,decision n.决定, 决心, 决议, decisive adj.决定性的destruction n.破坏, 毁灭destructive adj.破坏(性)的disaster n.灾难, 天灾, 灾祸disastrous adj.损失惨重的, 悲伤的east n.东方, 东, 东部地区eastward adv.向东eat v.吃, 腐蚀edible adj.可食用的elder n.年长者, 老人, 父辈elderly adj.过了中年的, 稍老的energy n.精力, 精神, 活力, [物]能量energetic adj.精力充沛的, 积极的enthusiasm n.狂热, 热心, 积极性,enthusiastic adj.热心的, 热情的error n.错误, 过失, 误差erroneous adj.错误的, 不正确的exception adv.排外地, 专有地exceptional adj.例外的, 异常的exclusively adv.排外地, 专有地exclusive adj.排外的, 孤高的,female n.女性, 女人, 雌兽feminine adj.妇女(似)的, 娇柔的,give n.弹性, 可弯性given adj.赠予的, 沉溺的, 特定的globe n.球体, 地球仪, 地球, 世界global adj.球形的, 全球的, 全世界的grace n.优美, 雅致, 优雅gracious adj.亲切的, 高尚的haste n.匆忙, 急忙hasty adj.匆忙的, 草率的historical adj.历史(上)的, 有关历史的historic adj.历史上著名的, 有历史性的horror n.惊骇, 恐怖, 惨事, 极端厌恶horrible adj.可怕的, 恐怖的, 讨厌的imagine vt.想象, 设想imaginative adj.想象的, 虚构的include vt.包括, 包含inclusive adj.包含的, 包括的indicate vt.指出, 显示, 象征, indicative adj.(~ of) 指示的, 预示的, 可表示的infect vt.[医] 传染, 感染infectious adj.有传染性的, 易传染的,instant adj.立即的, 直接的, instantaneous adj.瞬间的, 即刻的, 即时的instrument n.工具, 手段, 器械, 器具, 手段instrumental adj.仪器的, 器械的, 乐器的intention n.意图, 目的intent n.意图, 目的, 意向,valuable adj.贵重的, 有价值的invaluable adj.无价的, 价值无法衡量的legal adj.法律的, 法定的, 合法legitimate adj.合法的, 合理的, 正统的line n.绳, 索, 线路, 航线, 诗句linear adj.线的, 直线的, 线性的literary adj.文学(上)的, 从事写作的literal adj.文字的, 照字面上的margin n.页边的空白,marginal adj.记在页边的, 边缘的, 边际的mass n.块, 大多数, 质量, 群众, 大量massive adj.厚重的, 大块的, 魁伟的, 结实的metal n.金属metallic adj.金属(性)的might n.力量, 威力, 权力, 能, 可能mighty n.有势力的人military adj.军事的, 军用的militant adj.好战的, 积极从事或支持使用武力的minimum adj.最小的, 最低的minimal adj.最小的, 最小限度的mud n.泥, 泥浆, 泥泞muddy adj.多泥的, 泥泞的muscle n.肌肉, 臂力,muscular adj.肌肉的, 强健的neglect vt.忽视, 疏忽, 漏做negligible adj.可以忽略的, 不予重视的note n.笔记, 短信, (外交)照会notable adj.值得注意的, 显著的, 著名的number n.数, 数字, numerical adj.数字的, 用数表示的obey v.服从, 顺从obedient adj.服从的, 孝顺的permit n.通行证, 许可证, 执照permissible adj.可允许的, 可容许程度的period n.时期, 学时, periodic adj.周期的, 定期的persist vi.坚持, 持续persistent adj.持久稳固的mature adj.成熟的, premature adj.未成熟的, 太早的, 早熟的prevail vi.流行, 盛行, 获胜, 成功prevalent adj.普遍的, 流行的product n.产品, 产物, 乘积productive adj.生产性的, 生产的,profit n.利润, 益处, 得益profitable adj.有利可图的promise vt.允诺, 答应promising adj.有希望的, 有前途的prospect n.景色, 前景, 前途, 期望prospective adj.预期的quality n.质量, 品质, 性质qualitative adj.性质上的, 定性的quantity n.量, 数量quantitative adj.数量的, 定量的radiation n.发散, 发光, 发热,radiant adj.发光的, 辐射的, 容光焕发的reality n.真实, 事实, 本体, 逼真realistic adj.现实(主义)的republic n.共和国, 共和政体republican adj.共和国的, 共和政体的,residence n.居住, 住处residential adj.住宅的, 与居住有关的result n.结果, 成效, 计算结果resultant adj.作为结果而发生的, 合成的sex n.性别, 男性或女性, sexual adj.性的, 性别的, [生]有性的shade n.荫, 阴暗, 荫凉处,shady adj.成荫的, 多荫的, 阴暗的situation n.情形, 境遇, (situated adj.位于,被置于境遇,处于...的立场space n.空间, 间隔, 距离, spacious adj.广大的, 大规模的strategy n.策略, 军略strategic adj.战略的, 战略上的strike n.罢工, 打击, 殴打striking adj.打击的, 显著的,subject n.题目, 主题,subjective adj.主观的, 个人的supplement n.补遗, 补充, supplementary adj.附助的suspicion n.猜疑, 怀疑suspicious adj.(~ of) 可疑的, 怀疑的tolerance n.公差, 宽容, tolerant adj.容忍的, 宽恕的, 有耐药力的tragedy n.悲剧, 惨案, tragic adj.悲惨的, 悲剧的triumph n.胜利, 成功triumphant adj.胜利的, 成功的,verb n.[语]动词verbal adj.口头的virtually adv.事实上, 实质上virtual adj.虚的, 实质的,wear vt.穿, 戴weary adj.疲倦的, 厌倦的,wool n.羊毛, 毛织品, woolen adj.毛纺的advshore n.岸, 海滨, 支撑柱ashore adv.向岸地, 在岸上地bare adj.赤裸的, 无遮蔽的barely adv.仅仅, 刚刚, 几乎不能clock adj.赤裸的, 无遮蔽的, 空的clockwise adj.顺时针方向的incident n.事件, 事变incidentally adv.附带地, 顺便提及readily adv.乐意地, 欣然, 容易地ready adj.有准备的, 准备完毕的, 甘心的,seem vi.象是, 似乎seemingly adv.表面上地specific n.特效药, 细节specifically adv.特定的, 明确的normal n.正规, 常态, [数学]法线abnormal adj.反常的, 变态的able adj.能...的, 有才能的,disable v.使残废, 使失去能力, 丧失能力count v.数, 计算, 计算在内,discount n.折扣doubtful adj.可疑的, 不确的, 疑心的doubtless adj.无疑的, 确定的grade n.等级, 级别degrade v.(使)降级, (使)堕落, (使)退化infinite n.无限的东西finite adj.有限的, [数]有穷的place n.地方, 地点, displace vt.移置, 转移, 取代, 置换definite adj.明确的, 一定的indefinite adj.模糊的, 不确定的fortune n.财富, 运气, misfortune n.不幸, 灾祸。

上海环球金融中心英语介绍The Shanghai World Financial Center, often referred to as the SWFC, is an iconic skyscraper located in the Pudong district of Shanghai, China. Completed in 2008, it stands at a remarkable height of 492 meters (1,614 feet) and features 101 floors, making it one of the tallest buildings in the world. The structure is noted for its distinctive design, characterized by a large, rectangular opening at the top, giving it a unique silhouette that resembles a bottle opener. This innovative architectural choice was the result of a design competition in which the winning concept was developed by the architectural firm Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates.The SWFC is not only a stunning piece of modern architecture but also serves multiple purposes. It houses office spaces, luxury hotels, retail outlets, and observation decks. The building's lower floors are dedicated to retail,featuring high-end brands and dining options that cater to both tourists and locals. Above the retail level, thebuilding accommodates numerous offices that host both local and international firms, thereby establishing itself as a significant business hub in Shanghai.One of the most popular features of the Shanghai World Financial Center is its observation deck, located on the 94th floor. This deck offers visitors breathtaking panoramic views of the Shanghai skyline, including the nearby Oriental Pearl Tower, Jin Mao Tower, and the historic Bund area. The observation deck attracts millions of visitors each year, contributing to the building's reputation as a must-visit landmark in Shanghai.The SWFC is an exemplary representation of modern engineering and design. The building's construction involved advanced technologies and sustainable practices, emphasizing the importance of environmental consciousness in contemporaryarchitecture. Its glass facades and energy-efficient systems showcase efforts to minimize carbon footprints while maximizing natural light.In addition to its architectural appeal, the Shanghai World Financial Center plays a significant role in the economic landscape of Shanghai. It symbolizes the city’s rapid growth and its status as a global financial center. The building has also hosted various conferences, events, and exhibitions, further cementing its place in Shanghai’s dynamic business environment.Overall, the Shanghai World Financial Center stands as a testament to modern architectural innovation, urban development, and economic growth. It has become a defining feature of Shanghai's skyline and continues to attract visitors and businesses from around the world, embodying the city's ambitious spirit and forward-thinking vision.。

英语关于名胜古迹的手抄报名胜古迹手抄报(标题)Exploring Famous Landmarks(插图)图片插入多张著名名胜古迹的图片,如埃及金字塔、中国长城、法国埃菲尔铁塔、印度泰姬陵等。

(正文)Introduction:Famous landmarks are iconic structures and sites that represent a country's history, culture, and natural beauty. These landmarks attract millions of tourists every year, showcasing the wonders of human creation and natural marvels.1. Great Wall of China:The Great Wall of China is one of the world's most renowned architectural marvels. Stretching over 13,000 miles, it was built to protect China from invasions. It offers breathtaking views and a journey through history.2. Pyramids of Egypt:The pyramids of Egypt are mysterious and awe-inspiring. Built as tombs for ancient pharaohs, these grand structures leave visitors captivated. The famous pyramids of Giza, including the Great Pyramid, are astonishing feats of engineering.3. Eiffel Tower:The Eiffel Tower in Paris, France, is an iconic symbol of the cityand a marvel of modern engineering. Its towering iron structure attracts millions of visitors who enjoy panoramic views of Paris from its observation decks.4. Taj Mahal:The Taj Mahal, located in Agra, India, is a symbol of eternal love. This white marble mausoleum was built by Emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his beloved wife. Its intricate architectural details and stunning gardens make it a UNESCO World Heritage Site.(插图)为每个名胜古迹插入一幅配图。

中西方传统建筑异同作文英语120The Similarities and Differences Between Chinese and Western Traditional Architecture.Architecture, as a reflection of culture and history, has evolved uniquely in both China and the West. Each tradition possesses distinct characteristics that have been shaped by geography, climate, materials, and societal values. In this essay, we will delve into the intriguing similarities and profound differences between Chinese and Western traditional architecture.Similarities:1. Functional Purpose: Both Chinese and Western architecture have been designed to fulfill specific functional needs. Whether it is a palace for royalty, a temple for worship, or a house for the common people, the primary purpose of architecture is to provide shelter and a space for human activity.2. Symbolic Representation: Both traditions employ architecture as a means of symbolic representation. In China, the Forbidden City represents the absolute power of the emperor, while in the West, cathedrals symbolize the grandeur of God and the church.3. Aesthetic Appeal: Both Chinese and Western architecture aim for aesthetic appeal. The intricate carvings, elaborate designs, and harmonious proportions found in both traditions demonstrate a shared pursuit of beauty.4. Use of Natural.。

什么是TOGAF?企业架构师必备的4个架构域什么是Togaf?TOGAF9.2基础+鉴定是一个4天的连贯性培训体系,它从企业战略环境出发,介绍企业架构的基本概念和实践,引入架构开发方法(ADM)和2项指引和9项技术、需求分析和管理,再从架构内容框架、架构治理、架构能力模型全方位地解析企业架构的实践。

∙TOGAF标准是一个架构框架,即开放群组架构框架(The Open Group Architecture Framework)。

∙TOGAF标准由客户倡议发起∙TOGAF标准是由The Open Group架构论坛来开发和维护的。

∙TOGAF标准是一个框架(Framework)∙它是一个通用框架,可用于开发满足不同业务需要的各种架构。

∙它不是一个“one-size-fits-all”的架构∙它是一种工具,用来帮助架构的接受、创建、使用和维护。

∙它基于一个迭代的过程模型,由一些最佳实践和一套可重用的已有架构资产支持。

Architecture Domain架构域?The architectural area being considered.The TOGAF framework has four primary architecture domains:business,data,application,and technology.Other domains may also be considered(e.g.,security).Togaf标准定义的4个架构域如下:Business Architecture业务架构?A representation of holistic,multi-dimensional business views of:capabilities,end-to-end value delivery,information,and organizational structure;and the relationships among these business views and strategies,products,policies,initiatives,and stakeholders.Togaf业务架构如下:Application Architecture应用架构?A deion of the structure and interaction of the applications as groups of capabilities that provide key business functions and manage the data assets.Togaf应用架构如下:Data Architecture数据架构?A deion of the structure and interaction of the enterprise's major types and sources of data,logical data assets,physical data assets,and data management resources.Togaf数据架构如下:什么是数据先行or应用先行?阶段C包括数据架构和应用架构,开发顺序任意。

企业架构描述语言ArchiMate v1.01.架构语言ArchiMate -架构视角(Viewpoint)分类框架实现和维护一个一致的架构是一件非常复杂的任务,因为架构会涉及到很多不同背景的人员,他们使用不同的标记。

为了处理这种复杂性,研究人员开始关注如何为不同的涉众定义清晰的架构描述,本章介绍一下架构视角和视图的一些概念,在大家理解了这些基本概念之后,下一章我将会对ArchiMate 中的基本视角进行介绍。

2.架构描述概念模型大家都知道的有4+1 视图模型,业界还有其他一些软件体系结构表示方法,如ISO的一个标准RM-ODP,还有MDA中的Platform-Independent Model(PIM) and Platform-Specific Model (PSM),从这些模型来看,我们可以推断,在软件架构方面,通过视角(ViewPoint)和架构视图进行架构的描述已经是被大家接受的一个概念。

在企业架构-如何描述企业架构中对视角和视图也进行了一些描述。

下图为架构描述的概念模型,图中列出了主要的一些概念:•系统(System):一套满足特定功能的组件•架构(Architecture):系统的基本组织结构,包含组件以及它们之间的关系和环境,架构将指导系统的设计和演进•架构描述(Architecture Description):一套描述架构的工件。

在TOGAF 中,架构视图是架构描述的主要工件。

•涉众(Stakeholder):在系统中承担角色,或者关注系统某方面的人,例如用户、开发人员、管理人员等。

不同涉众有不同的关注点,涉众可以是个人、团队或者组织。

•关注点(Concern):涉众对系统感兴趣的地方,是决定系统是否被接受的重要因素。

关注点可以是系统功能、开发、操作、性能、安全等各个方面。

•视角(Viewpoint):定义企业架构表现的抽象模型,每个模型针对的是特定类型涉众的特定关注点。

•视图(View):视角的一个具体表现,它是有目的的传递架构信息的一种很好的方法。

Introduction to Chinese ArchitectureChinese architecture is an exquisite and diverse art form that has a rich history dating back thousands of years. With its unique blend of tradition and innovation, Chinese buildings are recognized worldwide for their distinctive features and cultural significance. In this article, we will introduce some key aspects of Chinese architecture.Traditional Architectural StylesTraditional Chinese architecture can be categorized into several styles, each with its own characteristics and influences. One of the well-known styles is Imperial Architecture, characterized by grandeur and meticulous craftsmanship. The Forbidden City in Beijing is a remarkable example of this style, with its majestic palaces and carefully designed layouts.Another prominent style is Buddhist Architecture, which is prevalent in temples and monasteries across China. These buildings often feature majestic pagodas and intricate decorations, showcasing the influence of Buddhism in Chinese culture. The Shaolin Temple is a famous example, renowned for its historical significance and martial arts heritage.Moreover, Garden Architecture is an integral part of Chinese architectural tradition. Chinese gardens are known for their harmonious integration of nature and man-made structures. Such gardens often include pavilions, winding paths, and serene water features. The Classical Gardens of Suzhou, with their exquisite design and tranquil scenery, serve as an excellent representation of this style.Architectural ElementsSeveral architectural elements are unique to Chinese buildings and contribute to their distinct style. One such element is the Chinese Roof, characterized by its upward-sweeping eaves and intricate details. These roofs are typically built with colorful glazed tiles and represent a significant aspect of Chinese architectural aesthetics.Another essential feature is the Decorative Woodwork, which manifests in intricate carvings on beams, columns, and door frames. These patterns often incorporate symbolic motifs, such as dragons and phoenixes, which hold cultural and spiritual significance.Furthermore, Courtyards play a vital role in Chinese architecture, providing open spaces for social activities and natural lighting. Chinese buildings often have a series of interconnected courtyards, creating a sense of spatial hierarchy and promoting a harmonious relationship between the indoors and outdoors.Feng Shui and Cultural SignificanceIn Chinese architecture, the concept of Feng Shui holds great importance. Feng Shui is the practice of arranging buildings and spaces harmoniously to promote balance and harmony. It takes into account factors such as orientation, layout, and the flow of energy. Following Feng Shui principles ensures a fruitful and prosperous living environment.Chinese architecture also reflects the country’s rich cultural heritage and philosophical beliefs. The emphasis on harmony and balance stems from the ancient philosophy of Confucianism, which greatly influenced Chinese society and its architectural traditions.Contemporary DevelopmentsWhile preserving its traditional roots, Chinese architecture has also embraced modern influences and innovative designs in recent years. Many cities in China exhibit awe-inspiring skyscrapers, futuristic structures, and avant-garde designs. The B ird’s Nest stadium in Beijing, designed for the 2008 Olympic Games, is an iconic example of contemporary Chinese architecture.ConclusionChinese architecture is an extraordinary blend of artistic expression, cultural symbolism, and functional design. Its rich history, traditional styles, and distinctive elements make it a fascinating subject of study. From ancient temples to modern skyscrapers, Chinese architecture continues to captivate and inspire individuals worldwide.。

Architecture: The Expression of Creativity, Functionality, andAestheticsArchitecture is an art form that embraces both aesthetics and functionality. It is a reflection of the creativity and ingenuity of mankind, serving as a tangible representation of human achievements throughout history. This article explores the significance and characteristics of architecture, highlighting its role in shaping our built environment.The Essence of ArchitectureArchitecture encompasses the design, planning, and construction of structures that fulfill various human needs. It involves the meticulous crafting of spaces, forms, and materials to create functional and visually appealing structures.Beyond mere construction, architecture reflects the culture, values, and aspirations of a society. It is a testament to human innovation and the desire to create living spaces that enhance our quality of life. Through architecture, we express our identity and leave a lasting legacy for future generations.The Elements of ArchitectureArchitecture encompasses several key elements that contribute to its overall design and purpose.1. Form and StructureThe form and structure of a building are essential aspects of architecture. Buildings are carefully designed to withstand environmental factors such as wind, earthquakes, and climate conditions. The structural integrity of a building ensures the safety and longevity of its occupants.2. FunctionalityFunctionality is another crucial aspect of architecture. Well-designed spaces should cater to the needs of their occupants. Architects consider factors such as space allocation, circulation, and the efficient use of natural light and ventilation to create functional spaces that promote productivity and well-being.3. AestheticsAesthetics play a vital role in architecture, as buildings shape our visual landscape. Architectural design balances form and function to create visually stimulating structures that captivate and inspire. The use of colors, materials, and textures define the aesthetic quality and character of a building.4. Context and EnvironmentArchitecture does not exist in isolation; it is deeply intertwined with its surroundings. Architects carefully consider the context and environment in which a building will be situated. This includes factors such as climate, topography, and cultural heritage. By harmonizing with its surroundings, a building contributes to the overall coherence and beauty of its environment.Architectural Styles and MovementsThroughout history, different architectural styles and movements have emerged, showcasing the evolution of architectural design.1. Classical ArchitectureClassical architecture, often associated with ancient Greece and Rome, is characterized by its symmetrical and proportioned designs. It features elements such as columns, arches, and domes, embodying a sense of harmony and balance.2. Gothic ArchitectureGothic architecture emerged during the medieval period, with its intricate stonework, pointed arches, and ribbed vaults. It is renowned for its tall, soaring structures and the extensive use of stained glass windows, creating a spiritual and ethereal aesthetic.3. ModernismModernism, which emerged in the 20th century, aimed to break away from traditional styles and embrace new materials and technologies. Modernist buildings often feature clean lines, geometric shapes, and an emphasis on functionalism.4. PostmodernismPostmodernism challenged the principles of modernism and emphasized diversity, ornamentation, and contextualism. Postmodern architecture often combines elements from various styles, creating visually striking and expressive structures.The Impact of ArchitectureArchitecture has a profound impact on our daily lives and the societies we inhabit.1. Cultural IdentityArchitecture is an expression of cultural identity. It serves as a visual representation of a community’s history, values, and aspirations. Iconic structuresbecome cultural landmarks, symbolizing the collective pride and achievements of a society.2. Sustainable DesignIn recent years, the importance of sustainable architecture has gained significant attention. Architects are increasingly incorporating environmentally friendly design principles to minimize the ecological footprint of buildings. Concepts such as green roofs, solar energy systems, and natural ventilation contribute to a more sustainable built environment.3. Urban PlanningArchitecture plays a crucial role in urban planning and city development. Well-designed buildings and public spaces foster social interaction, create a sense of place, and enhance overall livability. Architecture contributes to the creation of harmonious and functional cities.ConclusionArchitecture is more than just building construction; it is an amalgamation of creativity, functionality, and artistic expression. It shapes our environment, providing structures that resonate with our cultural identity and enhance our well-being. From the grandeur of classical architecture to the innovation of modern design, architecture stands as a testament to human achievement and the pursuit of beauty and functionality.。

关于椅子的英语作文Chairs have been an integral part of human civilization for centuries. They have evolved from simple stools and benches to intricate and ergonomic designs that cater to our diverse needs and preferences. The chair, as a piece of furniture, has not only served as a functional object but has also become a symbol of status, comfort, and creativity.At the most fundamental level, chairs provide a means for us to sit and rest our bodies. They offer support to our backs, legs, and arms, allowing us to maintain a comfortable and upright position for extended periods. This basic function has remained unchanged throughout the evolution of chair design, but the ways in which chairs have been crafted and adorned have transformed significantly.In ancient civilizations, chairs were often reserved for the elite and powerful. The Egyptians, for example, created ornate and elaborately decorated chairs for their pharaohs, incorporating symbols of their divine status and cultural heritage. Similarly, the ancient Greeks and Romans designed chairs that reflected their architectural styles andsocietal hierarchies. These early chairs were not only functional but also served as statements of wealth and prestige.As societies progressed and the concept of comfort and ergonomics gained prominence, chair design began to evolve. The introduction of new materials, such as wood, metal, and later, plastic, allowed for greater flexibility in shaping and molding chairs to fit the human form more effectively. Designers and engineers started to experiment with different configurations, angles, and support systems to provide better posture alignment and weight distribution.One of the most significant advancements in chair design came with the introduction of the swivel chair. This innovation, credited to American inventor Thomas Jefferson, allowed for greater mobility and ease of movement, making it particularly useful in office settings. The swivel chair paved the way for the development of the modern office chair, which has become a ubiquitous feature in workplaces around the world.Beyond their functional purposes, chairs have also become a canvas for artistic expression. Renowned designers and craftspeople have pushed the boundaries of chair design, creating pieces that blur the line between furniture and sculpture. From the iconic Eames Lounge Chair to the whimsical designs of Marc Newson, chairs have become objects of beauty and admiration, showcasing the creative potentialof the human mind.In the realm of interior design, chairs have played a crucial role in shaping the ambiance and aesthetic of a space. The choice of chair can instantly set the tone of a room, whether it's the sleek and modern chairs in a contemporary living room or the cozy and inviting armchairs in a traditional library. Chairs have the power to define the mood, reflect the personal style of the occupants, and even influence the overall functionality of a space.The significance of chairs extends beyond their physical form and into the realm of symbolism and cultural significance. In many societies, the type of chair one occupies can convey social status, authority, and even religious or political affiliation. The "throne," for example, has long been associated with the power and sovereignty of a ruler, while the "hot seat" in a courtroom or interview setting can represent the vulnerability and scrutiny of the individual occupying it.Furthermore, chairs have become important cultural artifacts, with certain designs and styles being closely tied to specific eras, movements, and geographical regions. The Chippendale chair, for instance, is a testament to the craftsmanship and design sensibilities of 18th-century England, while the Barcelona chair is a quintessential representation of the modernist movement in architecture and design.As we move into the future, the role of chairs in our lives is likely to continue evolving. Advancements in materials, technology, and ergonomic research will undoubtedly lead to even more innovative and sophisticated chair designs. Furthermore, the increasing emphasis on sustainability and environmental consciousness may inspire designers to explore more eco-friendly materials and production methods, further enhancing the chair's versatility and relevance in our ever-changing world.In conclusion, the humble chair has a rich and fascinating history that reflects the ingenuity, creativity, and cultural evolution of human civilization. From the ornate thrones of ancient kings to the sleek and minimalist designs of modern-day offices, chairs have been a constant companion in our lives, serving as both functional objects and symbols of our values, aspirations, and artistic sensibilities. As we continue to explore and push the boundaries of chair design, we can be certain that this ubiquitous piece of furniture will remain an integral part of our lives, shaping the way we interact with our physical environments and with one another.。

在我心中最难忘的标志性建筑英语作文The Most Unforgettable Iconic Building in My HeartIn every city, there are always some iconic buildings that leave a deep impression on us. These buildings may have a special historical significance, a unique architectural design, or a symbolic representation of the city. Among all the iconic buildings I have seen, the one that stands out the most in my heart is the Sydney Opera House in Australia.The Sydney Opera House is undoubtedly one of the most famous and recognizable buildings in the world. Its unique design, with its sail-like roof structure, has become a symbol of not only Sydney but of all of Australia. Designed by the Danish architect Jørn Utzon, the opera house was officially opened in 1973 and has since become a UNESCO World Heritage Site.I still remember the first time I laid eyes on the Sydney Opera House. It was a clear and sunny day, and as I walked along the Circular Quay, I was struck by the beauty and grandeur of the building. The white shells of the roof seemed to glisten in the sunlight, and the architecture was unlike anything I had ever seen before. I stood there for a long time, just taking in the sight and feeling a sense of awe and wonder.I was lucky enough to attend a performance at the Sydney Opera House during my visit to Australia. The interior of the building was just as stunning as the exterior, with its elegant halls and theatres. The acoustics were superb, and the performance was truly unforgettable. The combination of the world-class music and the magnificent setting of the opera house made it an experience I will never forget.The Sydney Opera House has not only left a lasting impression on me but has also become a symbol of the city of Sydney. Whenever I see a picture of the opera house or hear someone mention it, I am instantly transported back to that day when I first saw it in person. It is a building that has a special place in my heart, and I hope to visit it again someday.In conclusion, the Sydney Opera House is the most unforgettable iconic building in my heart. Its unique design, historical significance, and cultural importance make it a truly remarkable structure. I feel fortunate to have had the opportunity to see it in person and experience its beauty and grandeur. The Sydney Opera House will always hold a special place in my heart as a symbol of Sydney and a reminder of the power of great architecture.。