韩素音青年翻译奖赛13

- 格式:docx

- 大小:30.84 KB

- 文档页数:15

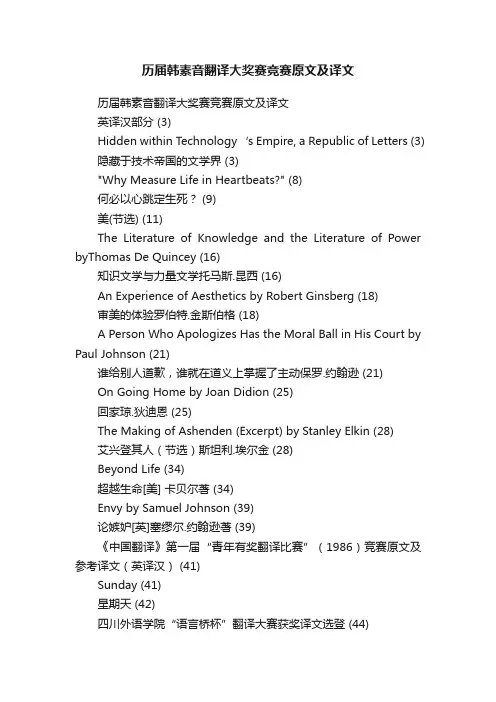

历届韩素音翻译大奖赛竞赛原文及译文历届韩素音翻译大奖赛竞赛原文及译文英译汉部分 (3)Hidden within Technology‘s Empire, a Republic of Letters (3)隐藏于技术帝国的文学界 (3)"Why Measure Life in Heartbeats?" (8)何必以心跳定生死? (9)美(节选) (11)The Literature of Knowledge and the Literature of Power byThomas De Quincey (16)知识文学与力量文学托马斯.昆西 (16)An Experience of Aesthetics by Robert Ginsberg (18)审美的体验罗伯特.金斯伯格 (18)A Person Who Apologizes Has the Moral Ball in His Court by Paul Johnson (21)谁给别人道歉,谁就在道义上掌握了主动保罗.约翰逊 (21)On Going Home by Joan Didion (25)回家琼.狄迪恩 (25)The Making of Ashenden (Excerpt) by Stanley Elkin (28)艾兴登其人(节选)斯坦利.埃尔金 (28)Beyond Life (34)超越生命[美] 卡贝尔著 (34)Envy by Samuel Johnson (39)论嫉妒[英]塞缪尔.约翰逊著 (39)《中国翻译》第一届“青年有奖翻译比赛”(1986)竞赛原文及参考译文(英译汉) (41)Sunday (41)星期天 (42)四川外语学院“语言桥杯”翻译大赛获奖译文选登 (44)第七届“语言桥杯”翻译大赛获奖译文选登 (44)The Woods: A Meditation (Excerpt) (46)林间心语(节选) (47)第六届“语言桥杯”翻译大赛获奖译文选登 (50)第五届“语言桥杯”翻译大赛原文及获奖译文选登 (52)第四届“语言桥杯”翻译大赛原文、参考译文及获奖译文选登 (54) When the Sun Stood Still (54)永恒夏日 (55)CASIO杯翻译竞赛原文及参考译文 (56)第三届竞赛原文及参考译文 (56)Here Is New York (excerpt) (56)这儿是纽约 (58)第四届翻译竞赛原文及参考译文 (61)Reservoir Frogs (Or Places Called Mama's) (61)水库青蛙(又题:妈妈餐馆) (62)中译英部分 (66)蜗居在巷陌的寻常幸福 (66)Simple Happiness of Dwelling in the Back Streets (66)在义与利之外 (69)Beyond Righteousness and Interests (69)读书苦乐杨绛 (72)The Bitter-Sweetness of Reading Yang Jiang (72)想起清华种种王佐良 (74)Reminiscences of Tsinghua Wang Zuoliang (74)歌德之人生启示宗白华 (76)What Goethe's Life Reveals by Zong Baihua (76)怀想那片青草地赵红波 (79)Yearning for That Piece of Green Meadow by Zhao Hongbo (79)可爱的南京 (82)Nanjing the Beloved City (82)霞冰心 (84)The Rosy Cloud byBingxin (84)黎明前的北平 (85)Predawn Peiping (85)老来乐金克木 (86)Delights in Growing Old by Jin Kemu (86)可贵的“他人意识” (89)Calling for an Awareness of Others (89)教孩子相信 (92)To Implant In Our Children‘s Young Hearts An Undying Faith In Humanity (92)心中有爱 (94)Love in Heart (94)英译汉部分Hidden within Technology’s Empire, a Republic of Le tters 隐藏于技术帝国的文学界索尔·贝娄(1)When I was a boy ―discovering literature‖, I used to think how wonderful it would be if every other person on the street were familiar with Proust and Joyce or T. E. Lawrence or Pasternak and Kafka. Later I learned how refractory to high culture the democratic masses were. Lincoln as a young frontiersman read Plutarch, Shakespeare and the Bible. But then he was Lincoln.我还是个“探索文学”的少年时,就经常在想:要是大街上人人都熟悉普鲁斯特和乔伊斯,熟悉T.E.劳伦斯,熟悉帕斯捷尔纳克和卡夫卡,该有多好啊!后来才知道,平民百姓对高雅文化有多排斥。

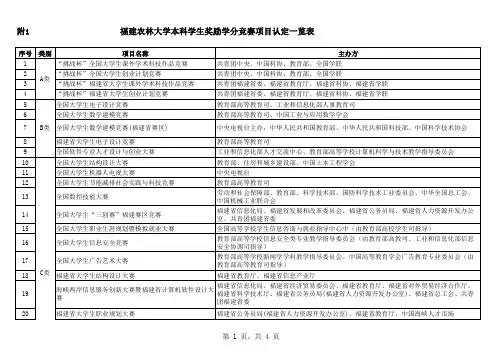

附1 福建农林大学本科学生奖励学分竞赛项目认定一览表

说明:(1)A类:国家部委,或省级政府及其所属的厅局等主管部门举办的“挑战杯”大学生课外学术科技作品竞赛、创业计划大赛。

B类:作为福建省普通高等学校内涵建设主要评价指标学生竞赛。

C类 :国家部委及其所属的司局,或省级政府及其所属的厅局等正厅级以上主管部门举办的未列入福建省普通高等学校内涵建设主要评价指标的学生单项学科竞赛。

D类:国家级学会、团体,或国际知名学会、团体举办的学生单项学科竞赛。

E类:省级学会、协会、团体,或国家级学会的分会组织的单项学科竞赛。

F类:由省级以上政府部门、学会、团体举办的文艺赛事。

(2)竞赛项目所属类别随主办方和内涵评价的变动而进行相应的调整。

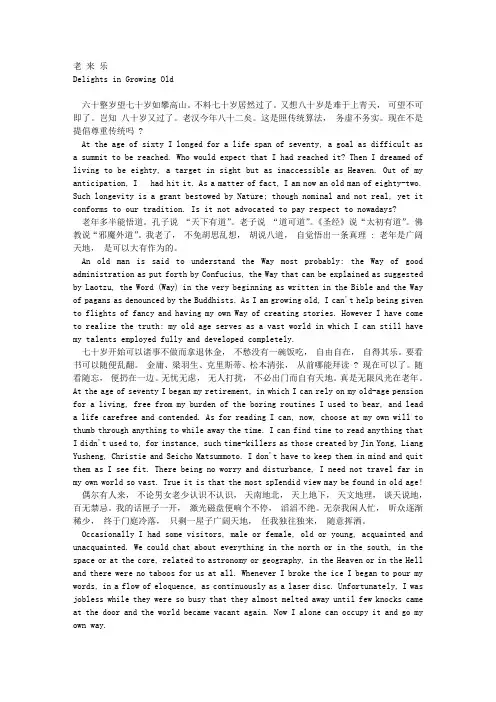

老来乐Delights in Growing Old六十整岁望七十岁如攀高山。

不料七十岁居然过了。

又想八十岁是难于上青天,可望不可即了。

岂知八十岁又过了。

老汉今年八十二矣。

这是照传统算法,务虚不务实。

现在不是提倡尊重传统吗 ?At the age of sixty I longed for a life span of seventy, a goal as difficult as a summit to be reached. Who would expect that I had reached it? Then I dreamed of living to be eighty, a target in sight but as inaccessible as Heaven. Out of my anticipation, I had hit it. As a matter of fact, I am now an old man of eighty-two. Such longevity is a grant bestowed by Nature; though nominal and not real, yet it conforms to our tradition. Is it not advocated to pay respect to nowadays?老年多半能悟道。

孔子说“天下有道”。

老子说“道可道”。

《圣经》说“太初有道”。

佛教说“邪魔外道”。

我老了,不免胡思乱想,胡说八道,自觉悟出一条真理 : 老年是广阔天地,是可以大有作为的。

An old man is said to understand the Way most probably: the Way of good administration as put forth by Confucius, the Way that can be explained as suggested by Laotzu, the Word (Way) in the very beginning as written in the Bible and the Way of pagans as denounced by the Buddhists. As I am growing old, I can't help being given to flights of fancy and having my own Way of creating stories. However I have come to realize the truth: my old age serves as a vast world in which I can still have my talents employed fully and developed completely.七十岁开始可以诸事不做而拿退休金,不愁没有一碗饭吃,自由自在,自得其乐。

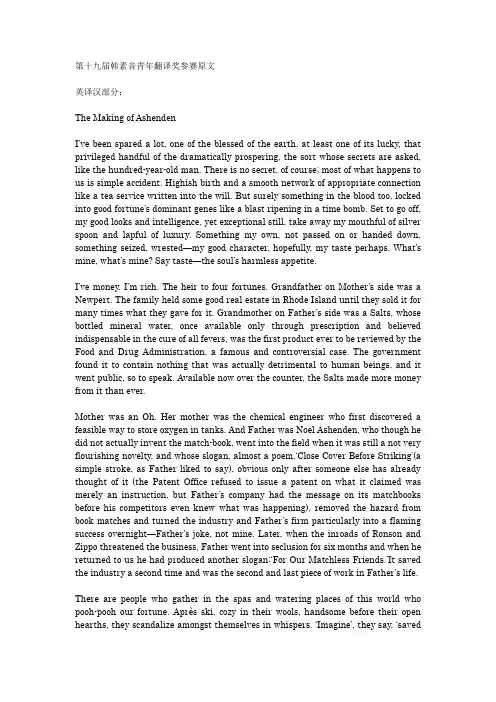

第十九届韩素音青年翻译奖参赛原文英译汉部分:The Making of AshendenI’ve been spared a lot, one of the blessed of the earth, at least one of its lucky, that privileged handful of the dramatically prospering, the sort whose secrets are asked, like the hundred-year-old man. There is no secret, of course; most of what happens to us is simple accident. Highish birth and a smooth network of appropriate connection like a tea service written into the will. But surely something in the blood too, locked into good fortune’s dominant genes like a blast ripening in a time bomb. Set to go off, my good looks and intelligence, yet exceptional still, take away my mouthful of silver spoon and lapful of luxury. Something my own, not passed on or handed down, something seized, wrested—my good character, hopefully, my taste perhaps. What’s mine, what’s mine? Say taste—the soul’s harmless appetite.I’ve money, I’m rich. The heir to four fortunes. Grandfather on Mother’s side was a Newpert. The family held some good real estate in Rhode Island until they sold it for many times what they gave for it. Grandmother on Father’s side was a Salts, whose bottled mineral water, once available only through prescription and believed indispensable in the cure of all fevers, was the first product ever to be reviewed by the Food and Drug Administration, a famous and controversial case. The government found it to contain nothing that was actually detrimental to human beings, and it went public, so to speak. Available now over the counter, the Salts made more money from it than ever.Mother was an Oh. Her mother was the chemical engineer who first discovered a feasible way to store oxygen in tanks. And Father was Noel Ashenden, who though he did not actually invent the match-book, went into the field when it was still a not very flourishing novelty, and whose slogan, almost a poem,‘Close Cover Before Striking’(a simple stroke, as Father liked to say), obvious only after someone else has already thought of it (the Patent Office refused to issue a patent on what it claimed was merely an instruction, but Father’s company had the message on its matchbooks before his competitors even knew what was happening), removed the hazard from book matches and turned the industry and Father’s firm particularly into a flaming success overnight—Father’s joke, not mine. Later, when the inroads of Ronson and Zippo threatened the business, Father went into seclusion for six months and when he returned to us he had produced another slogan:‘For Our Matchless Friends.’It saved the industry a second time and was the second and last piece of work in Father’s life.There are people who gather in the spas and watering places of this world who pooh-pooh our fortune. Après ski, cozy in their wools, handsome before their open hearths, they scandal ize amongst themselves in whispers. ‘Imagine’, they say, ‘savedfrom ruin because of some cornball sentiment available in every bar and grill and truck stop in the country. It’s not, not...’Not what? Snobs! Phooey on the First Families. On railroad, steel mill, automotive, public utility, banking and shipping fortunes, on all hermetic legacy, morganatic and blockbuster blood-lines that change the maps and landscapes and alter the mobility patterns, your jungle wheeling and downtown dealing a stone’s throw from warfare. I come of good stock—real estate, mineral water, oxygen, matchbooks: earth, water, air and fire, the old elementals of the material universe, a bellybutton economics, a linchpin one.It is as I see it a perfect genealogy, and if I can be bought and sold a hundred times over by a thousand men in this country—people in your own town could do it, providents and trailers of hunch, I bless them, who got into this or went into that when it was eight cents a share—I am satisfied with my thirteen or fourteen million. Wealth is not after all the point. The genealogy is. That bridge-trick nexus that brought Newpert to Oh, Salts to Ashenden and Ashenden to Oh, love’s lucky longshots which, paying off, permitted me as they permit every human life! (I have this simple, harmless paranoia of the good-natured man, this cheerful awe.) Forgive my enthusiasm, that I go on like some secular patriot wrapped in the simple flag of self, a professional descendant, every day the closed-for-the-holiday banks and post offices of the heart. And why not? Aren’t my circumstances superb? Whose are better? No boast, no boast. I’ve had it easy, served up on all life’s silver platters like a satrap. And if my money is managed for me and I do no work—less work even than Father, who at least came up with those two slogans, the latter in a six-month solitude that must have been hell for that gregarious man (‘For Our Matchless Friends’: no slogan finally but a broken code, an extension of his own hospitable being, simply the Promethean gift of fire to a guest)—at least I am not ‘spoiled’ and have in me still alive the nerve endings of gratitude. If it’s miserly to count one’s blessings, Brewster Ashenden’s a miser.This will give you some idea of what I’m like:On Having an Account in a Swiss Bank: I never had one, and suggest you stay away from them too. Oh, the mystery and romance is all very well, but never forget that your Swiss bank offers no premiums, whereas for opening a savings account for 5,000 or more at First National City Bank of New York or other fine institutions you get wonderful premiums—picnic hampers, Scotch coolers, Polaroid cameras, Hudson’s Bay blankets from L. L. Bean, electric shavers, even lawn furniture. My managers always leave me a million or so to play wi th, and this is how I do it. I suppose I’ve received hundreds of such bonuses. Usually I give them to friends or as gifts at Christmas to doormen and other loosely connected personnel of the household, but often I keep them and use them myself. I’m not sti ngy. Of course I can afford to buy any of these things — and I do, I enjoy making purchases — but somehow nothing brings the joy of existence home to me more than these premiums. Something fromnothing — the two-suiter from Chase Manhattan and my own existence, luggage a bonus and life a bonus too. Like having a film star next to you on your flight from the Coast. There are treats of high order, adventure like cash in the street.Let’s enjoy ourselves, I say; let’s have fun. Lord, let us live in the sand b y the surf of the sea and play till cows come home. We’ll have a house on the Vineyard and a brownstone in the Seventies and a pied-à-terre in a world capital when something big is about to break. (Put the Cardinal in the back bedroom where the sun gilds the bay at afternoon tea and give us the courage to stand up to secret police at the door, to top all threats with threats of our own, the nicknames of mayors and ministers, the fast comeback at the front stairs, authority on us like the funny squiggle the counterfeiters miss.) Re-Columbus us. Engage us with the overlooked, a knowledge of optics, say, or a gift for the tides. (My pal, the heir to most of the vegetables in inland Nebraska, has become a superb amateur oceanographer. The marine studies people i nvite him to Wood’s Hole each year. He has a wave named for him.) Make us good at things, the countertenor and the German language, and teach us to be as easy in our amateur standing as the best man at a roommate’s wedding. Give us hard tummies behind the cummerbund and long swimmer’s muscles under the hound’s tooth so that we may enjoy our long life. And may all our stocks rise to the occasion of our best possibilities, and our humanness be bullish too.Speaking personally I am glad to be a heroic man.I am pleased that I am attractive to women but grateful I’m no bounder. Though I’m touched when married women fall in love with me, as frequently they do, I am rarely to blame. I never encourage these fits and do my best to get them over their derangements so as not to lose the friendships of their husbands when they are known to me, or the neutral friendship of the ladies themselves. This happens less than you might think, however, for whenever I am a houseguest of a married friend I usually make it a point to bring along a girl. These girls are from all walks of life—models, show girls, starlets, actresses, tennis professionals, singers, heiresses and the daughters of the diplomats of most of the nations of the free world. All walks. They tend, however, to conform to a single physical type, and are almost always tall, tan, slender and blond, the girl from Ipanema as a wag friend of mine has it. They are always sensitive and intelligent and good at sailing and the Australian crawl. They are never blemished in any way, for even something like a tiny beauty mark on the inside of a thigh or above the shoulder blade is enough to put me off, and their breaths must be as sweet at three in the morning as they are at noon. (I never see a woman who is dieting for diet sours the breath.) Arm hair, of course, is repellent to me though a soft blond down is now and then acceptable. I know I sound a prig. I’m not. I am—well, classical, drawn by perfection as to some magnetic, Platonic pole, idealism and beauty’s true North.。

比赛介绍:韩素音青年翻译大赛详解韩素音其人:韩素音,是中国籍亚欧混血女作家伊丽莎白·柯默(Elisabeth Comber)的笔名,原名周光湖(Rosalie Elisabeth Kuanghu Chow)。

她的主要作品取材于20世纪中国生活和历史,主要用英语、法语进行写作,1952年,韩素音用英文写就的自传体小说《瑰宝》(A Many Splendoured Thing)一出版即在西方世界引起轰动,奠定了她在国际文坛上的地位。

1955年,美国20世纪福克斯公司把《瑰宝》搬上银幕,译名《生死恋》(Love Is A Many Splendoured Thing)。

韩素音女士现居瑞士。

韩素音青年翻译奖:《中国翻译》杂志从1986年开始举办青年“有奖翻译”活动,1989年韩素音女士访华,提供了一笔赞助基金,以此设立了“韩素音青年翻译奖”。

至2010年,“韩素音青年翻译奖”竞赛已经举办了二十二届,是目前中国翻译界组织时间最长、规模最大、影响最广的翻译大赛。

每年获奖人员来自社会各界,比赛并非是从所有译文中选出最好的就评为第一名,很多时候会出现第一名空缺的现象,因为评委组是按照严格的标准来筛选译文,没有最优秀的,第一名的位置就会空缺,由此可见韩素音翻译大赛的权威性和严谨性。

参与方式:韩素音青年翻译大赛由中国译协《中国翻译》编辑部主办(/),每届比赛设英译汉和汉译英两部分,每部分给出一篇要求翻译的文章,参赛者可以只选择一项,或者两项都参与。

注意,参赛者年龄为45岁以下——因为是青年翻译比赛。

参赛规则、竞赛原文和报名表会刊登在每年第一期,也即一月份的《中国翻译》杂志上,中国译协网站上也会有通知,大致规则如下:1. 参赛译文须独立完成。

参赛者在大赛截稿之日前需妥善保存参赛译文的著作权,不可在书报刊、网络等任何媒体公布自己的参赛译文,否则将被取消参赛资格并承担由此造成的一切后果。

2. 参赛译文请用空白A4纸打印(中文宋体、英文Times New Roman,小四,1.5倍行距)。

保护古村落就是保护“根性文化”To Preserve “Ancient Villages”, to Protect the “Roots of Culture”传统村落是指拥有物质形态和非物质形态文化遗产,具有较高的历史、文化、科学、艺术、社会、经济价值的村落。

但近年来,随着城镇化快速推进,以传统村落为代表的传统文化正在淡化,乃至消失。

对传统村落历史建筑进行保护性抢救,并对传统街巷和周边环境进行整治,可防止传统村落无人化、空心化。

“Traditional villages” refer to those with tangible and intangible cultural heritages and of high historic, cultural, scientific, artistic, social and economic value. But in recent years, traditional cultures represented by traditional villages have been fading away or even dying out with rapid urbanization. In order to prevent those villages from being uninhabited or hollowed out, we must protect historic buildings at risk there, restore the old streets and lanes, and renovate their surroundings.古村落与其说是老建筑,倒不如说是一座座承载了历史变迁的活建筑文化遗产,任凭世事变迁,斗转星移,古村落依然岿然不动,用无比顽强的生命力向人们诉说着村落的沧桑变迁,尽管曾经酷暑寒冬,风雪雨霜,但是古老的身躯依然支撑着生命的张力,和生生不息的人并肩生存,从这点上说,沧桑的古村落也是一种无形的精神安慰。

中国译协《中国翻译》编辑部与江苏人文环境艺术设计研究院(中国译协江苏培训中心)联合举办第二十四届韩素音青年翻译奖竞赛。

具体参赛规则如下:一、本届竞赛分别设立英译汉和汉译英两个奖项,参赛者可任选一项或同时参加两项竞赛。

二、《中国翻译》2012年第1期以及中国译协网()韩素音青年翻译奖专栏刊登竞赛规则、竞赛原文;参赛报名表请到中国翻译协会网站韩素音青年翻译奖专栏下载。

三、参赛者年龄:45岁以下(1967年1月1日后出生)。

四、参赛译文须独立完成,杜绝抄袭现象,一经发现,将取消参赛资格。

请参赛者在大赛截稿之日前妥善保存参赛译文,请勿在书报刊、网络等任何媒体公布自己的参赛译文,否则将被取消参赛资格并承担由此造成的一切后果。

五、参赛译文和参赛报名表格式要求:参赛译文应为WORD电子文档,中文宋体、英文Times New Roman字体,全文小四号字,1.5倍行距,文档命名格式为“XXX(姓名)英译汉”或“XXX(姓名)汉译英”。

参赛报名表文档命名格式为“XXX(姓名)英译汉参赛报名表”或“XXX(姓名)汉译英参赛报名表”。

译文正文内请勿书写译者姓名、地址等任何个人信息,否则将被视为无效译文。

每项参赛译文一稿有效,恕不接收修改稿。

六、参赛方式及截稿日期:请参赛者于2012年5月31日(含)前将参赛译文及参赛报名表以电子文档附件形式发送至hansuyin2012@,发送成功的文档得到自动回复后,请勿重复发送。

如需查询是否发送成功,可在6月10日至7月10日之间拨打电话(010)68997177。

本届竞赛不再接收打印稿。

七、参赛者在提交参赛译文后,交寄报名费50元,如同时参加两项竞赛,请交报名费 100元。

汇款地址:北京市阜外百万庄大街24号《中国翻译》编辑部,收款人:《中国翻译》编辑部,邮编:100037。

请在汇款单附言上注明“XXX(姓名)参赛报名费”字样。

未交报名费的参赛译文无效。

八、本届竞赛设一、二、三等奖和优秀奖若干名,一、二、三等奖获得者将被授予奖金、奖杯、证书和纪念品,优秀奖获得者将被授予证书和纪念品。

“CATTI杯”第二十七届韩素音青年翻译奖竞赛英译汉竞赛原文:The Posteverything GenerationI never expected to gain any new insight into the nature of my generation, or the changing landscape of American colleges, in Lit Theory. Lit Theory is supposed to be the class where you sit at the back of the room with every other jaded sophomore wearing skinny jeans, thick-framed glasses, an ironic tee-shirt and over-sized retro headphones, just waiting for lecture to be over so you can light up a Turkish Gold and walk to lunch while listening to Wilco. That’s pretty much the way I spent the course, too: through structuralism, formalism, gender theory, and post-colonialism, I was far too busy shuffling through my Ipod to see what the patriarchal world order of capitalist oppression had to do with Ethan Frome. But when we began to study postmodernism, something struck a chord with me and made me sit up and look anew at the seemingly blasécollege-aged literati of which I was so self-consciously one.According to my textbook, the problem with defining postmodernism is that it’s impossible. The difficulty is that it is so...post. It defines itself so negatively against what came before it –naturalism, romanticism and the wild revolution of modernism –that it’s sometimes hard to see what it actually is. It denies that anything can be explained neatly or even at all. It is parodic, detached, strange, and sometimes menacing to traditionalists who do not understand it. Although it arose in the post-war west (the term was coined in 1949), the generation that has witnessed its ascendance has yet to come up with an explanation of what postmodern attitudes mean for the future of culture or society. The subject intrigued me because, in a class otherwise consumed by dead-letter theories, postmodernism remained an open book, tempting to the young and curious. But it also intrigued me because the question of what postmodernism –what a movement so post-everything, so reticent to define itself –is spoke to a larger question about the political and popular culture of today, of the other jaded sophomores sitting around mewho had grown up in a postmodern world.In many ways, as a college-aged generation, we are also extremely post: post-Cold War, post-industrial, post-baby boom, post-9/11...at one point in his famous essay, “Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism,”literary critic Frederic Jameson even calls us “post-literate.” We are a generation that is riding on the tail-end of a century of war and revolution that toppled civilizations, overturned repressive social orders, and left us with more privilege and opportunity than any other society in history. Ours could be an era to accomplish anything.And yet do we take to the streets and the airwaves and say “here we are, and this is what we demand”? Do we plant our flag of youthful rebellion on the mall in Washington and say “we are not leaving until we see change! Our eyes have been opened by our education and our conception of what is possible has been expanded by our privilege and we demand a better world because it is our right”? It would seem we do the opposite. We go to war without so much as questioning the rationale, we sign away our civil liberties,we say nothing when the Supreme Court uses Brown v. Board of Education to outlaw desegregation, and we sit back to watch the carnage on the evening news.On campus, we sign petitions, join organizations, put our names on mailing lists, make small-money contributions, volunteer a spare hour to tutor, and sport an entire wardrobe’s worth of Live Strong bracelets advertising our moderately priced opposition to everything from breast cancer to global warming. But what do we really stand for? Like a true postmodern generation we refuse to weave together an overarching narrative to our own political consciousness, to present a cast of inspirational or revolutionary characters on our public stage, or to define a specific philosophy. We are a story seemingly without direction or theme, structure or meaning –a generation defined negatively against what came before us. When Al Gore once said “It’s the combination of narcissism and nihilism that really defines postmodernism,” he might as well have been echoing his entire generation’s critique of our own. We are a generation for whom evenrevolution seems trite, and therefore as fair a target for bland imitation as anything else. We are the generation of the Che Geuvera tee-shirt.Jameson calls it “Pastiche”–“the wearing of a linguistic mask, speech in a dead language.” In literature, this means an author speaking in a style that is not his own –borrowing a voice and continuing to use it until the words lose all meaning and the chaos that is real life sets in. It is an imitation of an imitation, something that has been re-envisioned so many times the original model is no longer relevant or recognizable. It is mass-produced individualism, anticipated revolution. It is why postmodernism lacks cohesion, why it seems to lack purpose or direction. For us, the post-everything generation, pastiche is the use and reuse of the old clichés of social change and moral outrage –a perfunctory rebelliousness that has culminated in the age of rapidly multiplying non-profits and relief funds. We live our lives in masks and speak our minds in a dead language –the language of a society that expects us to agitate because that’s whatyoung people do. But how do we rebel against a generation that is expecting, anticipating, nostalgic for revolution?How do we rebel against parents that sometimes seem to want revolution more than we do? We don’t. We rebel by not rebelling. We wear the defunct masks of protest and moral outrage, but the real energy in campus activism is on the internet, with websites like . It is in the rapidly developing ability to communicate ideas and frustration in chatrooms instead of on the streets, and channel them into nationwide projects striving earnestly for moderate and peaceful change: we are the generation of Students Taking Action Now Darfur; we are the Rock the V ote generation; the generation of letter-writing campaigns and public interest lobbies; the alternative energy generation.College as America once knew it –as an incubator of radical social change –is coming to an end. To our generation the word “radicalism”evokes images of al Qaeda, not the Weathermen. “Campus takeover”sounds more like Virginia Tech in 2007 than Columbia University in 1968. Such phrasesare a dead language to us. They are vocabulary from another era that does not reflect the realities of today. However, the technological revolution, the revolution, the revolution of the organization kid, is just as real and just as profound as the revolution of the 1960’s –it is just not as visible. It is a work in progress, but it is there. Perhaps when our parents finally stop pointing out the things that we are not, the stories that we do not write, they will see the threads of our narrative begin to come together; they will see that behind our pastiche, the post generation speaks in a language that does make sense. We are writing a revolution. We are just putting it in our own words.汉译英竞赛原文:保护古村落就是保护“根性文化”传统村落是指拥有物质形态和非物质形态文化遗产,具有较高的历史、文化、科学、艺术、社会、经济价值的村落。

On Going Home【概述】本文是 2001年第十三届“韩素音青年翻译奖”英译汉部分的参赛原文。

原文作者Joan Didion 是位散文文体大家,她的文章极有文采和个性,要贴切地表达成汉语确实要下一番功夫。

而这篇文章艰深的背景知识更是给准确翻译设置了很大障碍。

不了解该文的作者及其生活道路、创作思想,不了解文章的写作背景及反映的时代特征,好些地方会觉得把握不准,甚至一筹莫展。

【翻译要点评析】1 . the Canton dessert plates: 查英文词典我们可能会取“ the former name of Guangzhou ”这一释义,然后把这一部分译成“产自广州的甜点盘子”。

但 The Dolphin Reader (Hunt, 1990) 收录的 On Going Home 中对“ canton ”的注释为“ Fine Chinese porcelain ”。

据此注释,“ canton ”在这里应是指这些盘子的质地,而不是产地。

另外,《英汉辞海》(王同亿, 1987)里有“ Canton china ”词条,译文第一条为“广东瓷;广东瓷器,尤指青花瓷”;韦伯斯特电子词典( 2000 Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. Version 2.5. )有“ Canton ware ”词条,释义照录于下:“ ceramic ware exported from China especially during the 18 th and 19 th centuries by way of Canton and including blue-and-white and enameled porcelain and various ornamented stonewares ”(从中国出口的陶瓷器,特别是 18、19世纪期间经由广州出口的,包括青花上釉瓷器和各种有装饰的粗陶器)。

韩素音青年翻译奖竞赛原文第二十六届“韩素音青年翻译奖”竞赛原文英译汉竞赛原文:How the News Got Less MeanThe most read article of all time on BuzzFeed contains no photographs of celebrity nip slips and no inflammatory ranting. It’s a series of photos called “21 pictures that will restore your faith in humanity,”which has pulled in nearly 14 million visits so far. At Upworthy too, hope is the major draw. “This kid just died. What he left behind is wondtacular,”an Upworthy post about a terminally ill teen singer, earned 15 million views this summer and has raised more than $300,000 for cancer research.The recipe for attracting visitors to stories online is changing. Bloggers have traditionally turned to sarcasm and snark to draw attention. But the success of sites like BuzzFeed and Upworthy, whose philosophies embrace the viral nature of upbeat stories, hints that the Web craves positivity.The reason: social media. Researchers are discovering that people want to create positive images of themselves online by sharing upbeat stories. And with more people turning to Facebook and Twitter to find out what’s happening in the world, news stories may need to cheer up inorder to court an audience. If social is the future of media, then optimistic stories might be media’s future.“When we started, the prevailing wisdom was that snark ruled the Internet,”says Eli Pariser, a co-founder of Upworthy. “And we just had a really different sense of what works.”“You don’t want to be that guy at the party who’s crazy and angry and ranting in the corner —it’s the same for Twitteror Facebook,”he says. “Part of what we’re trying to d o with Upworthy is give people the tools to express a conscientious, thoughtful and positive identity in social media.”And the science appears to support Pariser’s philosophy. In a recent study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, researchers f ound that “up votes,”showing that a visitor liked a comment or story, begat more up votes on comments on the site, but “down votes”did not do the same. In fact, a single up vote increased the likelihood that someone else would like a comment by 32%, wherea s a down vote had no effect. People don’t want to support the cranky commenter, the critic or the troll. Nor do they want to be that negative personality online.In another study published in 2012, Jonah Berger, author of Contagious: Why Things Catch On and professor of marketing at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, monitored the most e-mailed stories produced by the New York Times for six months andfound that positive stories were more likely to make the list than negative ones.“What we share [or like] is almost like the car we drive or the clothes we wear,”he says. “It says something about us to other people. So people would much rather be seen as a Positive Polly than a Debbie Downer.”It’s not always that simple: Berger says that th ough positive pieces drew more traffic than negative ones, within the categories of positive and negative stories, those articles that elicited more emotion always led to more shares.“Take two negative emotions, for example: anger and sadness,”Berger says. “Both of those emotions would make the reader feel bad. But anger, a high arousal emotion, leads to moresharing, whereas sadness, a low arousal emotion, doesn’t. The same is true of the positive side: excitement and humor increase sharing, whereas conte ntment decreases sharing.”And while some popular BuzzFeed posts —like the recent “Is this the most embarrassing interview Fox News has ever done?”—might do their best to elicit shares through anger, both BuzzFeed and Upworthy recognize that their main success lies in creating positive viral material.“It’s not that people don’t share negative stories,”says Jack Shepherd, editorial director at BuzzFeed. “It just means that there’s ahigher potential for positive stories to do well.”Upworthy’s mission is to highlight serious issues but in a hopeful way, encouraging readers to donate money, join organizations and take action. The strategy seems to be working: barely two years after its launch date (in March 2012), the site now boasts 30 million unique visitors per month, according to Upworthy. The site’s average monthly unique visitors grew to 14 million people over its first six quarters —to put that in perspective, the Huffington Post had only about 2 million visitors in its first six quarters online.But Upworthy measures the success of a story not just by hits. The creators of the site only consider a post a success if it’s also shared frequently on social media. “We are interested in content that people want to share partly for pragmatic reasons,”Pariser s ays. “If you don’t have a good theory about how to appear in Facebook and Twitter, then you may disappear.”Nobody has mastered the ability to make a story go viral like BuzzFeed. The site, which began in 2006 as a lab to figure out what people share onlin e, has used what it’s learned to draw 60million monthly unique visitors, according to BuzzFeed. (Most of that traffic comes from social-networking sites, driving readers toward BuzzFeed’s mix of cute animal photos and hard news.) By comparison the New York Times website, one of the most popular newspaper sites on the Web,courts only 29 million unique visitors each month, according to the Times.BuzzFeed editors have found that people do still read negative or critical stories, they just aren’t the posts t hey share with their friends. And those shareable posts are the ones that newsrooms increasingly prize.“Anecdotally, I can tell you people are just as likely to click on negative stories as they are to click on positive ones,”says Shepherd. “But they’re m ore likely to share positive stories. What you’re interested in is different from what you want your friends to see what you’re interested in.”So as newsrooms re-evaluate how they can draw readers and elicit more shares on Twitter and Facebook, they may look to BuzzFeed’s and Upworthy’s happiness model for direction.“I think that the Web is only becoming more social,”Shepherd says. “We’re at a point where readers are your publishers. If news sites aren’t thinking about what it would mean for someone to share a story on social media, that could be detrimental.”汉译英竞赛原文:城市的迷失沿着瑗珲—腾冲线,这条1935年由胡焕庸先生发现并命名的中国人口、自然和历史地理的分界线,我们看到,从远距离贸易发展开始的那天起,利益和权力的渗透与分散,已经从根本结构上改变了城市的状态:城市在膨胀,人在疏离。

韩素音青年翻译奖竞赛 | 译文评析(下) 原创: 中国译协 中国翻译协会 2017-01-10第28届韩素音青年翻译奖竞赛参考译文及评析—(下)汉译英汉译英竞赛原文屠呦呦秉持的,不是好事者争论的随着诺贝尔奖颁奖典礼的临近,持续2个月的“屠呦呦热”正在渐入高潮。

当地时间7日下午,屠呦呦在瑞典卡罗林斯卡学院发表题为“青蒿素——中医药给世界的一份礼物”的演讲,详细回顾了青蒿素的发现过程,并援引毛泽东的话称,中医药学“是一个伟大的宝库”。

对中医药而言,无论是自然科学“圣殿”中的这次演讲,还是即将颁发到屠呦呦手中的诺奖,自然都提供了极好的“正名”。

置于世界科学前沿的平台上,中医药学不仅真正被世界“看见”,更能因这种“看见”获得同世界对话的机会。

拨开层层迷雾之后,对话是促成发展的动力。

将迷雾拨开、使对话变成可能,是屠呦呦及其团队的莫大功劳。

但如果像部分舆论那样,将屠呦呦的告白简单视作其对中医的“背书”,乃至将其成就视作中医向西医下的“战书”,这样的心愿固然可嘉,却可能完全背离科学家的本意。

听过屠呦呦的报告,或是对其研究略作了解就知道,青蒿素的发现既来自于中医药“宝库”提供的积淀和灵感,也来自于西医严格的实验方法。

缺了其中任意一项,历史很可能转向截然不同的方向。

换言之,在“诺奖级”平台上促成中西医对话之前,屠呦呦及其团队的成果,正是长期“对话”的成果。

而此前绵延不绝的“中西医”之争,多多少少都游离了对话的本意,而陷于一种单向化的“争短长”。

持中医论者,不屑于西医的“按部就班”;持西医论者,不屑于中医的“随心所欲”。

双方都没有看到,“按部就班”背后本是实证依据,“随心所欲”背后则有文化内涵,两者完全可以兼容互补,何必非得二元对立?屠呦呦在演讲中坦言,“通过抗疟药青蒿素的研究历程,我深深地感到中西医药各有所长,两者有机结合,优势互补,当具有更大的开发潜力和良好的发展前景”。

这既是站在中医药立场上对西方科学界的一次告白,反过来也可理解为西医立场上对中医拥趸们的提醒。

第十二届“韩素音青年翻译奖”竞赛原文及参考译文(汉译英)霞冰心四十年代初期,我在重庆郊外歌乐山闲居的时候,曾看到英文《读者文摘》上,有个很使我惊心的句子,是:May there be enough clouds in your life to make a beautiful sunset.我在一篇短文里曾把它译成:“愿你的生命中有够多的云翳,来造成一个美丽的黄昏。

”其实,这个sunset 应当译成“落照”或“落霞”。

霞,是我的老朋友了!我童年在海边、在山上,她都是我的最熟悉最美丽的小伙伴。

她每早每晚都在光明中和我说“早上好”或“明天见”。

但我直到几十年以后,才体会到云彩更多,霞光才愈美丽。

从云翳中外露的霞光,才是璀璨多彩的。

生命中不是只有快乐,也不是只有痛苦,快乐和痛苦是相生相成,互相衬托的。

快乐是一抹微云,痛苦是压城的乌云,这不同的云彩,在你生命的天边重叠着,在“夕阳无限好”的时候,就给你造成一个美丽的黄昏。

一个生命会到了“只是近黄昏”的时节,落霞也许会使人留恋、惆怅。

但人类的生命是永不止息的。

地球不停地绕着太阳自转。

东方不亮西方亮,我床前的晚霞,正向美国东岸的慰冰湖上走去……The Rosy CloudBingxinDuring the early 1940s I was living a retired life in the Gele Mountains in the suburbs of Chongqing (Chungking). One day, while reading the English language magazine Reader's Digest I found a sentence that touched me greatly. It read: "May there be enough clouds in your life to make a beautiful sunset."In a short article of mine, I quoted this sentence and translated it as "Yuan ni de shengming zhong you guo duo de yunyi, lai zaocheng yige meili de huanghun. " (literally: May there be enough clouds in your life to make a beautiful sunset.) *As I see it now, the word "sunset" in the English sentence should have been translated as luozhao (the glow at sunset) or luoxia (the rosy cloud at sunset), instead of dusk.She has been my dear old friend, the Rosy Cloud! She was my closest and most beautiful little companion when, in my childhood, I played on the beach or in the hills. Bathed in the brilliant sunshine, she would say to me "Good morning!" at dawn and "See you tomorrow!" at dusk. But not until several decades later did I come to realize that the more clouds there are the more beautiful the rays of sunlight will be, and the glow of the sun breaking through the clouds becomes most resplendent and colorful.Life contains neither unalloyed happiness nor mere misery. Happiness and misery beget, complement and set off each other.Happiness is a wisp of fleecy cloud; misery a mass of threatening dark cloud. These different clouds overlap on the horizon of your life to create a beautiful dusk for you when "the setting sun is most lovely indeed."**An individual's life must inevitably reach the point when "dusk is so near,"*** and the rosy sunset cloud may make one nostalgic and melancholy. But human life goes on and on. The Earth ceaselessly rotates on its axis around the sun. When it is dark in the east, it is light in the west. The rosy sunset cloud is now sailing past my window towards Lake Waban on the east coast of America ...*This sentence appears in Chinese and English in the article "For Young Readers Again, Newsletter No.4", written by Bing Xin in the Gele Mountains, on December 1, 1944.** and *** These two poetic lines are taken from a poem "On the Plain of Tombs" by Li Shangyin (813-858), a well-known poet of the Tang Dynasty (618-907). The two lines read like this: "The setting sun appears sublime, / But O! 'Tis near its dying time." (Tr. Xu Yuanchong) They imply that the setting sun has infinite beauty, but it is a pity that it is near the dusk, and the beautiful scene cannot last long. The two lines are often used to deplore the ephemeral nature of things, and to express the feelings at the loss of past glory and at the advent of old age.。

英译汉原文:Are We There Yet?America’s recovery will be much slower than that from most recessions; but the government can help a bit.“WHITHER goest thou, America?” That question, posed by Jack Kerouac on behalf of the Beat generation half a century ago, is the biggest uncertainty hanging over the world economy. And it reflects the foremost worry for American voters, who go to the polls for the congressional mid-term elections on November 2nd with the country’s unemployment rate stubbornly stuck at nearly one in ten. They should prepare themselves for a long, hard ride.The most wrenching recession since the 1930s ended a year ago. But the recovery—none too powerful to begin with—slowed sharply earlier this year. GDP grew by a feeble 1.6% at an annual pace in the second quarter, and seems to have been stuck somewhere similar since. The housing market slumped after temporary tax incentives to buy a home expired. So few private jobs were being created that unemployment looked more likely to rise than fall. Fears grew over the summer that if this deceleration continued, America’s economy would slip back into recession.Fortunately, those worries now seem exaggerated. Part of the weakness of second-quarter GDP was probably because of a temporary surge in imports from China. The latest statistics, from reasonably good retail sales in August to falling claims for unemployment benefits, point to an economy that, though still weak, is not slumping further. And history suggests that although nascent recoveries often wobble for a quarter or two, they rarely relapse into recession. For now, it is most likely that America’s economy will crawl along with growth at perhaps 2.5%: above stall speed, but far too slow to make much difference to the jobless rate.Why, given that America usually rebounds from recession, are the prospects so bleak? That’s because most past recessions have been caused by tight monetary policy. When policy is loosened, demand rebounds. This recession was the result of a financial crisis. Recoveries after financial crises are normally weak and slow as banking systems are repaired and balance-sheets rebuilt. Typically, this period of debt reduction lasts around seven years, which means America would emerge from it in 2014. By some measures, households are reducing their debt burdens unusually fast, but even optimistic seers do not think the process is much more than half over.Battling on the busAmerica’s biggest problem is that its poli ticians have yet to acknowledge that the economy is in for such a long, slow haul, let alone prepare for the consequences.A few brave officials are beginning to sound warnings that the jobless rate is likely to “stay high”. But the political debate is mor e about assigning blame for the recession than about suggesting imaginative ways to give more oomph to the recovery. Republicans argue that Barack Obama’s shift towards “big government” explainsthe economy’s weakness, and that high unemployment is proof t hat fiscal stimulus was a bad idea. In fact, most of the growth in government to date has been temporary and unavoidable; the longer-run growth in government is more modest, and reflects the policies of both Mr Obama and his predecessor. And the notion that high joblessness “proves” that stimulus failed is simply wrong. The mechanics of a financial bust suggest that without a fiscal boost the recession would have been much worse.Democrats have their own class-warfare version of the blame game, in which Wall Street’s excesses caused the problem and higher taxes on high-earners are part of the solution. That is why Mr. Obama’s legislative priority before the mid-terms is to ensure that the Bush tax cuts expire at the end of this year for households earning more than $250,000 but are extended for everyone else.This takes an unnecessary risk with the short-term recovery. America’s experience in 1937 and Japan’s in 1997 are powerful evidence that ill-timed tax rises can tip weak economies back into recession. Higher taxes at the top, along with the waning of fiscal stimulus and belt-tightening by the states, will make a weak growth rate weaker still. Less noticed is that Mr. Obama’s fiscal plan will also worsen the medium-term budget mess, by making tax cuts for the middle class permanent.Ways to overhaul the engineIn an ideal world America would commit itself now to the medium-term tax reforms and spending cuts needed to get a grip on the budget, while leaving room to keep fiscal policy loose for the moment. But in febrile, partisan Washington that is a pipe-dream. Today’s goals can only be more modest: to nurture the weak economy, minimize uncertainty and prepare the ground for tomorrow’s fiscal debate. To that end, Congress ought to extend all the Bush tax cuts until 2013. Then they should all expire—prompting a serious fiscal overhaul, at a time when the economy is stronger.A broader set of policies could help to work off the hangover faster. One priority is to encourage more write-downs of mortgage debt. Almost a quarter of all Americans with mortgages owe more than their houses are worth. Until that changes the vicious cycle of rising foreclosures and falling prices will continue. There are plenty of ideas on offer, from changing the bankruptcy law so that judges can restructure mortgage debt to empowering special trustees to write down loans. They all have drawbacks, but a fetid pool of underwater mortgages will, much like Japan’s loans to zombie firms, corrode the financial system and harm the recovery.C leaning up the housing market would help cut America’s unemployment rate, by making it easier for people to move to where jobs are. But more must be done to stop high joblessness becoming entrenched. Payroll-tax cuts and credits to reduce the cost of hiring would help. (The health-care reform, alas, does the opposite, at least for small businesses.) Politicians will also have to think harder about training schemes, because some workers lack the skills that new jobs require.Americans are used to great distances. The sooner they, and their politicians, acceptthat the road to recovery will be a long one, the faster they will get there.译文:我们到达目的地了吗?与大多数衰退之后的复苏相比,这次美国经济的复苏会慢得多。

第十三届“韩素音青年翻译奖”竞赛原文及参考译文(汉译英)2010-3-26 23:32|发布者: sisu04|查看: 881|评论: 0摘要: 韩素音青年翻译奖歌德之人生启示宗白华人生是什么?人生的真相如何?人生的意义何在?人生的目的是何?这些人生最重大最中心的问题,不只是古来一切大宗教家哲学家所殚精竭虑以求解答的。

世界上第一流的大诗人凝神冥想,深入灵魂的幽邃,或纵身大化中,于一朵花中窥见天国,一滴露水参悟生命,然后用他们生花之笔,幻现层层世界,幕幕人生,归根也不外乎启示这生命的真相与意义。

宗教家对这些问题的方法与态度是预言的说教的,哲学家是解释的说明的,诗人文豪是表现的启示的。

荷马的长歌启示了希腊艺术文明幻美的人生与理想,但丁的神曲启示了中古基督教文化心灵的生活与信仰,莎士比亚的剧本表现了文艺复兴时人们的生活矛盾与权力意志。

至于近代的,建筑于这三种文明精神之上而同时开展一个新时代,所谓近代人生,则由伟大的歌德以他的人格,生活,作品表现出它的特殊意义与内在的问题。

歌德对人生的启示有几层意义,几种方面。

就人类全体讲,他的人格与生活可谓极尽了人类的可能性。

他同时是诗人,科学家,政治家,思想家,他也是近代泛神论信仰的一个伟大的代表。

他表现了西方文明自强不息的精神,又同时具有东方乐天知命宁静致远的智慧。

德国哲学家息默尔(Simmel)说:“歌德的人生所以给我们以无穷兴奋与深沉的安慰的,就是他只是一个人,他只是极尽了人性,但却如此伟大,使我们对人类感到有希望,鼓动我们努力向前做一个人。

“我们可以说歌德是世界一扇明窗,我们由他窥见了人生生命永恒幽邃奇丽广大的天空!再狭小范围,就欧洲文化的观点说,歌德确是代表文艺复兴以后近代人的心灵生活及其内在的问题。

近代人失去了基督教对一超越上帝虔诚的信仰。

人类精神上获得了解放,得到了自由;但也就同时失所依傍,彷徨摸索,苦闷,追求,欲在生活本身的努力中寻得人生的意义与价值。

歌德是这时代精神伟大的代表,他的主著《浮士德》是这人生全部的反映与其问题的解决。

歌德与其替身浮士德一生生活的内容就是尽量体验这近代人生特殊的精神意义,了解其悲剧而努力以解决其问题,指出解救之道。

所以有人称他的浮士德是近代人的圣经。

但歌德与但丁莎士比亚不同的地方,就是他不单是由作品里启示我们人生真相,尤其在他自己的人格与生活中表现了人生广大精微的义谛。

What Goethe’s Life RevealsZong BaihuaWhat is life? What are the true nature, meaning and purpose of life? Since ancient times, great philosophers and scholars of religion have strained their energy and intellect to the limit for an answer to these crucial and central questions in a person’s life. But they are not alone. First-rate poets in the world have done the same by contemplating and pondering over the questions—now delving into the depth of their souls—now communing with Nature. They envision Paradise through a flower and see the meaning of life in a dewdrop. Then, with their gifted pens, they picture a kaleidoscopic world and act upon act of the drama of life. In the end their works serve no other purpose than revealing the truth and meaning of life. Faced with these questions, scholars of religion adopt the attitude and approach of trying to prophesy and exhort; philosophers to explain and expound; poets and men of letters to portray and reveal. Homer’s epics enlighten us about the kind of refined, colorful life and ideal in Greek art. Dante’s Divina Comedia reveals people’s minds and faith in the Christian culture of the Middle Ages. Shakespeare’s plays reflect the contradictions in men’s lives and the "will to power" during th e Renaissance. As to the kind of life in modern times, which derives from the three civilizations mentioned above and heralds a new age, it is the great Goethe who, through his personal character, life and works, demonstrates its special meaning and innate problems.Goethe reveals to us different layers and aspects of the meaning of life. Taking the human race as a whole, we may say that Goethe’s personality and life represent the best possible in man. He is at once a poet, scientist, statesman, thinker and an outstanding representative of pantheistic faiths of modern times. He is the embodiment of both the spirit of unremitting endeavor in western civilization and the oriental wisdom of easy contentment and internal peace with foresight. Simmel the German philosopher once said, "The reason that Goethe can give us infinite excitement and deep solace is that he is but a human being, and he does nothing more than bringing out the best in human nature. Yet he is so great, and his greatness makes one see the hopein mankind’s future and serves to encourage everyone of us to forge ahead and be a worthy man." We may say that Goethe is like a window on the world, through which we can see the eternal, serene, uniquely beautiful and boundless skies of life.In a narrower sense, viewed in the perspective of European culture, Goethe indeed represents people of the post-Renaissance period in terms of their intellectual life and their inner problems. In modern times people have abandoned their strong Christian faith in an omnipotent God. Their spirit has been emancipated and they have acquired freedom. Yet, on the other hand, they have lost what gave them strength. They are nervously groping in the dark; they are spiritually tormented; they engage in a quest, trying to find the true meaning and value of life through their mundane efforts. Goethe is a great representative of our Zeitgeist. His most important work, Faust, is a reflection of everything in this kind of life and a solution to its problems. All that Goethe and Dr Faust, his stand-in, do throughout their lives is to experience to the fullest the peculiar spirit and meaning of life in modern times, try to understand its tragedy, strive to solve its problems and show people the way of deliverance. This is why his Faust is deemed the Bible of modern times.But Goethe is different from Dante and Shakespeare, in that he does not merely enlighten us about the true meaning of life through his works. His personal character and behavior does even more in demonstrating the great and subtle truth of life.评第十三届“韩素音青年翻译奖”英译汉参考译文2006-2-28 15:43 【大中小】【打印】【我要纠错】【加入收藏】评第十三届“韩素音青年翻译奖”英译汉参考译文朱志瑜(香港理工大学中文及双语系)近年中国翻译研究发展很快,但翻译批评始终落后。