Henderson 等. - 1998 - Brand diagnostics Mapping branding effects using

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:493.33 KB

- 文档页数:22

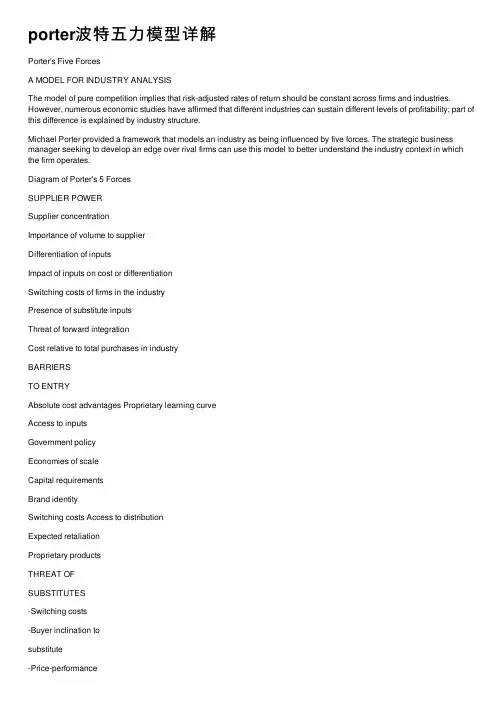

porter波特五⼒模型详解Porter's Five ForcesA MODEL FOR INDUSTRY ANALYSISThe model of pure competition implies that risk-adjusted rates of return should be constant across firms and industries. However, numerous economic studies have affirmed that different industries can sustain different levels of profitability; part of this difference is explained by industry structure.Michael Porter provided a framework that models an industry as being influenced by five forces. The strategic business manager seeking to develop an edge over rival firms can use this model to better understand the industry context in which the firm operates.Diagram of Porter's 5 ForcesSUPPLIER POWERSupplier concentrationImportance of volume to supplierDifferentiation of inputsImpact of inputs on cost or differentiationSwitching costs of firms in the industryPresence of substitute inputsThreat of forward integrationCost relative to total purchases in industryBARRIERSTO ENTRYAbsolute cost advantages Proprietary learning curveAccess to inputsGovernment policyEconomies of scaleCapital requirementsBrand identitySwitching costs Access to distributionExpected retaliationProprietary productsTHREAT OFSUBSTITUTES-Switching costs-Buyer inclination tosubstitute-Price-performancetrade-off of substitutes BUYER POWERBargaining leverageBuyer volumeBuyer informationBrand identityPrice sensitivityThreat of backward integrationProduct differentiationBuyer concentration vs. industrySubstitutes availableBuyers' incentivesDEGREE OF RIVALRY-Exit barriers-Industry concentration-Fixed costs/Value added-Industry growth-Intermittent overcapacity-Product differences-Switching costs-Brand identity-Diversity of rivals-Corporate stakesI. RivalryIn the traditional economic model, competition among rival firms drives profits to zero. But competition is not perfect and firms are not unsophisticated passive price takers. Rather, firms strive for a competitive advantage over their rivals. The intensity of rivalry among firms varies across industries, and strategic analysts are interested in these differences.Economists measure rivalry by indicators of industry concentration. The Concentration Ratio (CR) is one such measure. The Bureau of Census periodically reports the CR for major Standard Industrial Classifications (SIC's). The CR indicates the percent of market share held by the four largest firms (CR's for the largest 8, 25, and 50 firms in an industry also are available). A high concentration ratio indicates that a high concentration of market share is held by the largest firms - the industry is concentrated. With only a few firms holding a large market share, the competitive landscape is less competitive (closer to a monopoly). A low concentration ratio indicates that the industry is characterized by many rivals, none of which has a significant market share. These fragmented markets are said to be competitive. The concentration ratio is not the only available measure; the trend is to define industries in terms that convey more information than distribution of market share.If rivalry among firms in an industry is low, the industry is considered to be disciplined. This discipline may result from the industry's history of competition, the role of a leading firm, or informal compliance with a generally understood code of conduct. Explicit collusion generally is illegal and not an option; in low-rivalry industries competitive moves must be constrained informally. However, a maverick firm seeking a competitive advantage can displace the otherwise disciplined market.When a rival acts in a way that elicits a counter-response by other firms, rivalry intensifies. The intensity of rivalry commonly is referred to as being cutthroat, intense, moderate, or weak, based on the firms' aggressiveness in attempting to gain an advantage.In pursuing an advantage over its rivals, a firm can choose from several competitive moves:Changing prices - raising or lowering prices to gain a temporary advantage.Improving product differentiation - improving features, implementing innovations in the manufacturing process and in the product itself.Creatively using channels of distribution - using vertical integration or using a distribution channel that is novel to the industry. For example, with high-end jewelry stores reluctant to carry its watches, Timex moved intodrugstores and other non-traditional outlets and cornered the low to mid-price watch market.Exploiting relationships with suppliers - for example, from the 1950's to the 1970's Sears, Roebuck and Co. dominated the retail household appliancemarket. Sears set high quality standards and required suppliers to meet its demands for product specifications and price. The intensity of rivalry is influenced by the following industry characteristics:1. A larger number of firms increases rivalry because more firms mustcompete for the same customers and resources. The rivalry intensifies ifthe firms have similar market share, leading to a struggle for marketleadership.2.Slow market growth causes firms to fight for market share. In a growingmarket, firms are able to improve revenues simply because of theexpanding market.3.High fixed costs result in an economy of scale effect that increasesrivalry. When total costs are mostly fixed costs, the firm must producenear capacity to attain the lowest unit costs. Since the firm must sell thislarge quantity of product, high levels of production lead to a fight formarket share and results in increased rivalry.4.High storage costs or highly perishable products cause a producer tosell goods as soon as possible. If other producers are attempting tounload at the same time, competition for customers intensifies.5.Low switching costs increases rivalry. When a customer can freelyswitch from one product to another there is a greater struggle to capturecustomers.6.Low levels of product differentiation is associated with higher levels ofrivalry. Brand identification, on the other hand, tends to constrain rivalry.7.Strategic stakes are high when a firm is losing market position or haspotential for great gains. This intensifies rivalry.8.High exit barriers place a high cost on abandoning the product. The firmmust compete. High exit barriers cause a firm to remain in an industry,even when the venture is not profitable. A common exit barrier is assetspecificity. When the plant and equipment required for manufacturing aproduct is highly specialized, these assets cannot easily be sold to otherbuyers in another industry. Litton Industries' acquisition of IngallsShipbuilding facilities illustrates this concept. Litton was successful in the1960's with its contracts to build Navy ships. But when the Vietnam warended, defense spending declined and Litton saw a sudden decline in itsearnings. As the firm restructured, divesting from the shipbuilding plantwas not feasible since such a large and highly specialized investmentcould not be sold easily, and Litton was forced to stay in a decliningshipbuilding market.9. A diversity of rivals with different cultures, histories, and philosophiesmake an industry unstable. There is greater possibility for mavericks andfor misjudging rival's moves. Rivalry is volatile and can be intense. Thehospital industry, for example, is populated by hospitals that historicallyare community or charitable institutions, by hospitals that are associatedwith religious organizations or universities, and by hospitals that are for-profit enterprises. This mix of philosophies about mission has leadoccasionally to fierce local struggles by hospitals over who will getexpensive diagnostic and therapeutic services. At other times, localhospitals are highly cooperative with one another on issues such ascommunity disaster planning.10.Industry Shakeout. A growing market and the potential for high profitsinduces new firms to enter a market and incumbent firms to increaseproduction. A point is reached where the industry becomes crowded withcompetitors, and demand cannot support the new entrants and theresulting increased supply. The industry may become crowded if itsgrowth rate slows and the market becomes saturated, creating a situation of excess capacity with too many goods chasing too few buyers. Ashakeout ensues, with intense competition, price wars, and companyfailures.BCG founder Bruce Henderson generalized this observation as the Ruleof Three and Four: a stable market will not have more than threesignificant competitors, and the largest competitor will have no more thanfour times the market share of the smallest. If this rule is true, it impliesthat:o If there is a larger number of competitors, a shakeout is inevitableo Surviving rivals will have to grow faster than the marketo Eventual losers will have a negative cash flow if they attempt to growo All except the two largest rivals will be loserso The definition of what constitutes the "market" is strategicallyimportant.Whatever the merits of this rule for stable markets, it is clear that marketstability and changes in supply and demand affect rivalry. Cyclical demand tends to create cutthroat competition. This is true in the disposable diaper industry in which demand fluctuates with birth rates, and in the greetingcard industry in which there are more predictable business cycles.II. Threat Of SubstitutesIn Porter's model, substitute products refer to products in other industries. To the economist, a threat of substitutes exists when a product's demand is affected by the price change of a substitute product. A product's price elasticity is affected by substitute products - as more substitutes become available, the demand becomes more elastic since customers have more alternatives. A close substitute product constrains the ability of firms in an industry to raise prices.The competition engendered by a Threat of Substitute comes from products outside the industry. The price of aluminum beverage cans is constrained by the price of glass bottles, steel cans, and plastic containers. These containers are substitutes, yet they are not rivals in the aluminum can industry. To the manufacturer of automobile tires, tire retreads are a substitute. Today, new tires are not so expensive that car owners give much consideration to retreading old tires. But in the trucking industry new tires are expensive and tires must be replaced often. In the truck tire market, retreading remains a viable substitute industry. In the disposable diaper industry, cloth diapers are a substitute and their prices constrain the price of disposables.While the treat of substitutes typically impacts an industry through price competition, there can be other concerns in assessing the threat of substitutes. Consider the substitutability of different types of TV transmission: local station transmission to home TV antennas via the airways versus transmission via cable, satellite, and telephone lines. The new technologies available and the changing structure of the entertainment media are contributing to competition among these substitute means of connecting the home to entertainment. Except in remote areas it is unlikely that cable TV could compete with free TV from an aerial without the greater diversity of entertainment that it affords the customer.III. Buyer PowerThe power of buyers is the impact that customers have on a producing industry. In general, when buyer power is strong, the relationship to the producing industry is near to what an economist terms a monopsony - a market in which there are many suppliers and one buyer. Under such market conditions, the buyer sets the price. In reality few pure monopsonies exist, but frequently there is some asymmetry between a producing industry and buyers. The following tablesIV. Supplier PowerA producing industry requires raw materials - labor, components, and other supplies. This requirement leads to buyer-supplier relationships between the industry and the firms that provide it the raw materials used to create products. Suppliers, if powerful, can exert an influence on the producing industry, such as selling raw materials at a high price to capture some of the industry's profits. The following tables outline some factors that determine supplier power.V. Barriers to Entry / Threat of EntryIt is not only incumbent rivals that pose a threat to firms in an industry; the possibility that new firms may enter the industry also affects competition. In theory, any firm should be able to enter and exit a market, and if free entry and exit exists, then profits always should be nominal. In reality, however, industriespossess characteristics that protect the high profit levels of firms in the market and inhibit additional rivals from entering the market. These are barriers to entry. Barriers to entry are more than the normal equilibrium adjustments that markets typicallymake. For example, when industry profits increase, we would expect additional firms to enter the market to take advantage of the high profit levels, over time driving down profits for all firms in the industry. When profits decrease, we would expect some firms to exit the market thus restoring a market equilibrium. Falling prices, or the expectation that future prices will fall, deters rivals from entering a market. Firms also may be reluctant to enter markets that are extremely uncertain, especially if entering involves expensive start-up costs. These are normal accommodations to market conditions. But if firms individually (collective action would be illegal collusion) keep prices artificially low as a strategy to prevent potential entrants from entering the market, such entry-deterring pricing establishes a barrier.Barriers to entry are unique industry characteristics that define the industry. Barriers reduce the rate of entry of new firms, thus maintaining a level of profits for those already in the industry. From a strategic perspective, barriers can be created or exploited to enhance a firm's competitive advantage. Barriers to entry arise from several sources:/doc/c3dc3578eefdc8d377ee3243.html ernment creates barriers. Although the principal role of the government in a market is to preserve competition through anti-trustactions, government also restricts competition through the granting ofmonopolies and through regulation. Industries such as utilities areconsidered natural monopolies because it has been more efficient to have one electric company provide power to a locality than to permit manyelectric companies to compete in a local market. To restrain utilities fromexploiting this advantage, government permits a monopoly, but regulatesthe industry. Illustrative of this kind of barrier to entry is the local cablecompany. The franchise to a cable provider may be granted bycompetitive bidding, but once the franchise is awarded by a community amonopoly is created. Local governments were not effective in monitoringprice gouging by cable operators, so the federal government has enacted legislation to review and restrict prices.The regulatory authority of the government in restricting competition ishistorically evident in the banking industry. Until the 1970's, the marketsthat banks could enter were limited by state governments. As a result,most banks were local commercial and retail banking facilities. Bankscompeted through strategies that emphasized simple marketing devicessuch as awarding toasters to new customers for opening a checkingaccount. When banks were deregulated, banks were permitted to crossstate boundaries and expand their markets. Deregulation of banksintensified rivalry and created uncertainty for banks as they attempted tomaintain market share. In the late 1970's, the strategy of banks shiftedfrom simple marketing tactics to mergers and geographic expansion asrivals attempted to expand markets.2.Patents and proprietary knowledge serve to restrict entry into anindustry. Ideas and knowledge that provide competitive advantages aretreated as private property when patented, preventing others from usingthe knowledge and thus creating a barrier to entry. Edwin Land introduced the Polaroid camera in 1947 and held a monopoly in the instantphotography industry. In 1975, Kodak attempted to enter the instantcamera market and sold a comparable camera. Polaroid sued for patentinfringement and won, keeping Kodak out of the instant camera industry.3.Asset specificity inhibits entry into an industry. Asset specificity is theextent to which the firm's assets can be utilized to produce a differentproduct. When an industry requires highly specialized technology or plants and equipment, potential entrants are reluctant to commit to acquiringspecialized assets that cannot be sold or converted into other uses if theventure fails. Asset specificity provides a barrier to entry for two reasons:First, when firms already hold specialized assets they fiercely resist efforts by others from taking their market share. New entrants can anticipateaggressive rivalry. For example, Kodak had much capital invested in itsphotographic equipment business and aggressively resisted efforts by Fuji to intrude in its market. These assets are both large and industry specific.The second reason is that potential entrants are reluctant to makeinvestments in highly specialized assets./doc/c3dc3578eefdc8d377ee3243.html anizational (Internal) Economies of Scale. The most cost efficientlevel of production is termed Minimum Efficient Scale (MES). This is the point at which unit costs for production are at minimum - i.e., the most cost efficient level of production. If MES for firms in an industry is known, thenwe can determine the amount of market share necessary for low costentry or cost parity with rivals. For example, in long distancecommunications roughly 10% of the market is necessary for MES. If sales for a long distance operator fail to reach 10% of the market, the firm is not competitive.The existence of such an economy of scale creates a barrier to entry. The greater the difference between industry MES and entry unit costs, thegreater the barrier to entry. So industries with high MES deter entry ofsmall, start-up businesses. To operate at less than MES there must be aconsideration that permits the firm to sell at a premium price - such asproduct differentiation or local monopoly.Barriers to exit work similarly to barriers to entry. Exit barriers limit the ability of a firm to leave the market and can exacerbate rivalry - unable to leave the industry, a firm must compete. Some of an industry's entry and exit barriers can be summarized as follows:DYNAMIC NATURE OF INDUSTRY RIVALRYOur descriptive and analytic models of industry tend to examine the industry at a given state. The nature and fascination of business is that it is not static. While we are prone to generalize, for example, list GM, Ford, and Chrysler as the "Big 3" and assume their dominance, we also have seen the automobile industry change. Currently, the entertainment and communications industries are in flux. Phone companies, computer firms, and entertainment are merging and forming strategic alliances that re-map the information terrain. Schumpeter and, more recently, Porter have attempted to move the understanding of industry competition from a static economic or industry organization model to an emphasis on the interdependence of forces as dynamic, or punctuated equilibrium, as Porter terms it.In Schumpeter's and Porter's view the dynamism of markets is driven by innovation. We can envision these forces at work as we examine the following changes:GENERIC STRATEGIES TO COUNTER THE FIVE FORCES Strategy can be formulated on three levels:corporate levelbusiness unit levelfunctional or departmental level.The business unit level is the primary context of industry rivalry. Michael Porter identified three generic strategies (cost leadership, differentiation, and focus) that can be implemented at the business unit level to create a competitive advantage. The proper generic strategy will position the firm to leverage its strengths and defend against the adverse effects of the five forces.Recommended ReadingPorter, Michael E., Competitive Strategy:Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors Competitive Strategy is the basis for much of modern business strategy. In this classic work, Michael Porter presents his five forces and generic strategies, then discusses how to recognize and act on market signals and how to forecast the evolution of industry structure. He then discusses competitive strategy for emerging, mature, declining, and fragmented industries. The last part of the book covers strategic decisions related to vertical integration, capacity expansion, and entry into an industry. The book concludes with an appendix on how to conduct an industry analysis.QuickMBA / Strategy / Porters 5 ForcesHome | Site Map | About | Contact | Privacy | Reprints | User AgreementThe articles on this website are copyrighted material and may not be reproduced, stored on a computer disk, republished on another website, or distributed in any form without the prior express written permission of/doc/c3dc3578eefdc8d377ee3243.html .。

单位根检验的方法主要有以下几种:

1. ADF检验:即Augmented Dickey-Fuller检验,是对Dickey-Fuller检验的扩展,可以处理含有高阶滞后项的时间序列数据。

它通过在回归模型中加入差分滞后项来控制序列相关的干扰。

2. PP检验:即Phillips-Perron检验,与ADF检验类似,但使用非参数方法来修正序列相关的问题,对小样本性质有一定的改进。

3. KPSS检验:即Kwiatkowski-Phillips-Schmidt-Shin检验,是一种基于平稳序列的检验方法,原假设是序列是平稳的,而备择假设是序列存在单位根。

4. ERS检验:即Elliott-Rothenberg-Stock检验,是一种基于误差修正模型的单位根检验方法,适用于存在长期均衡关系的非平稳时间序列。

5. NP检验:即Nelson-Plosser检验,是一种专门用于检验宏观经济时间序列是否存在单位根的方法。

6. DF-GLS检验:即Dickey-Fuller Generalized Least Squares检验,是一种改进的Dickey-Fuller检验,使用广义最小二乘法来估计模型参数,以提高检验的功效。

7. 霍尔斯检验:即Hall测试,也是一种单位根检验方法,主要用于检测分数整合的存在。

8. 其他检验:还有一些其他的单位根检验方法,如Fisher类型的检验、Maddala-Wu检验等,它们在不同的情况下有各自的适用性和优势。

舍曲林对脑梗死急性期患者卒中后抑郁、神经功能及日常生活活动能力的影响张乾坤; 王昊亮; 宋景贵【期刊名称】《《河南医学研究》》【年(卷),期】2019(028)006【总页数】4页(P969-972)【关键词】舍曲林; 脑梗死急性期; 卒中后抑郁; 神经功能; 日常生活活动能力【作者】张乾坤; 王昊亮; 宋景贵【作者单位】新乡医学院第一附属医院神经内科河南新乡 453100【正文语种】中文【中图分类】R743.32卒中后抑郁(post stroke depression,PSD)是卒中后较为多见的并发症,极大影响患者神经功能恢复,并可能增加卒中后死亡率[1]。

研究报道,卒中早期预防性抗抑郁治疗可以明显改善患者精神状态,促进神经功能恢复[2-4]。

选择性5-羟色胺再摄取抑制剂(selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor,SSRI)类药物由于不良反应少、耐受性高在临床上被广泛应用。

本研究观察舍曲林对脑梗死急性期患者卒中后抑郁(PSD)、神经功能及日常生活活动能力的影响。

1 资料与方法1.1 一般资料选取2017年9—12月新乡医学院第一附属医院收治的180例脑梗死患者,按照随机数表法分为对照组和观察组,各90例。

对照组男39例,女53例;平均年龄(64.19±4.82)岁;合并高血压49例、糖尿病23例、心脏病17例、吸烟史57例、饮酒史42例。

观察组男43例,女47例;平均年龄(63.66±5.43)岁;合并高血压57例、糖尿病19例、心脏病21例、吸烟史63例、饮酒史38例。

两组患者一般资料比较,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

患者及家属自愿参与本研究并签署知情同意书。

本研究经新乡医学院第一附属医院医学伦理委员会审批通过。

1.2 选取标准纳入标准:符合1995年全国第四届脑血管病学术会议制定的急性脑血管病诊断标准[5];头颅CT或MRI确诊为首次脑梗死;发病时间大于6 h且小于48 h;年龄小于85岁。

常见的有《南加利福尼亚大学测验》、《芝加哥大学创造力测验》、《沃利奇-凯根测验》等。

常见的创造力人格测量工具有《发现才能团体问卷》、《你属于哪一类人》、《探究兴趣问卷》。

《发现才能团体问卷》是瑞姆(S.Rimm)和戴维斯(G.Davis)分别于1976年和1980年研究出来的一种测试方法。

其使用世界上最早的创造力测试Posted by Ray | Posted in 创造力小故事| Posted on 18-10-2010标签:创造力, 故事, 测试X您好!如果您是第一次光临意享博客, 您可能需要订阅本站的内容以及更新.Power ed by WP Gr ee t B ox Word Pres s Pl ugin美国心理学家吉尔福特先生被很多人奉为现代创造力之父,这主要是源自50年前的一次心理学会议。

当时吉尔福特发表了一篇令人耳目一新的关于创造力的讲话,引发了人们对于创造力的极大兴趣,也让更多人开始思考这个话题。

其妙的是,在二战期间吉尔福特是一名心理学家,被指派设计一组性格测试,用来测试飞行员的性格,以便挑选出最适合作为轰炸机飞行员的人选。

于是,吉尔福特从智力方面入手,设计了一套评分系统和面试规则,用来挑选飞行员。

而另他难以接受的是,空军机构指派了一名没有任何心理学知识的人来帮助他筛选。

尽管这个人是一名退役的飞行员,但吉尔福特并不信任这位帮手。

最终,吉尔福特与退役飞行员从候选人中选择了截然不同的人选。

结果之后的统计评审结果显示,吉尔福特挑选的飞行员被击落毙命的人数,要比退役飞行员所挑选的飞行员多出很多。

吉尔福特非常沮丧,认为自己将如此之多的飞行员送上绝路,甚至一度想要自杀。

不过最终他再次振作起来,决心要找出退役飞行员挑选的人选比较出色的原因。

经过交流,吉尔福特得知,这位退役飞行员问了所有候选人这样一个问题:“在飞越德国领空时,你不幸遭遇德军的防空炮火攻击,这时你该怎么办?”随后,所有回答“我会上升飞到更高的高度”的候选人,都被退役飞行员淘汰,而那些违反飞行条例准则的人,例如回答“我可能我会俯冲”或“我会‘之’字形路线飞行”或“我会掉头避开火力”的人,却通过了面试。

肯德尔趋势检验实例-概述说明以及解释1.引言1.1 概述在肯德尔趋势检验实例这篇长文中,本文将对肯德尔趋势检验进行介绍和应用实例的探讨。

肯德尔趋势检验是一种用于分析非参数趋势的统计检验方法,它可以帮助我们判断两个变量是否存在趋势关系。

该检验方法是根据数据中的排序信息进行计算的,因此不需要对数据的分布做出任何假设。

本文的目的是通过具体的实例来展示和解释肯德尔趋势检验的原理和应用。

我们将首先介绍肯德尔趋势检验的基本概念和原理,包括其计算公式和统计量的含义。

然后,我们会通过一个实际案例来说明肯德尔趋势检验的具体应用过程,并对结果进行解读和讨论。

文章将从引言开始,介绍本文的结构和目的,明确读者可以从本文中获得的信息和知识点。

接着,我们将在正文部分详细介绍肯德尔趋势检验的概念和原理,包括其适用范围、计算方法和统计量的含义。

在应用实例部分,我们将选择一个具体的数据集,对其进行分析和检验,以展示肯德尔趋势检验的实际应用。

最后,我们将总结本文的内容,并对肯德尔趋势检验的重要性进行讨论和评价。

通过本文的阅读,读者将能够了解肯德尔趋势检验的基本概念和原理,理解其在实际问题中的应用方法,并掌握如何解读和解释检验结果。

同时,读者还可以通过本文对肯德尔趋势检验的重要性的讨论,深入思考该方法在科学研究和决策分析中的价值和作用。

1.2文章结构文章结构是指文章的整体组织框架,有助于读者更好地理解和阅读全文。

在这篇文章中,我们将按照以下结构展开讨论:第一部分是引言,主要包括概述、文章结构和目的。

在这一部分,我们将提供对肯德尔趋势检验实例文章的简要介绍,明确文章的目标和结构,使读者能够更好地理解文章内容和组织架构。

第二部分是正文,分为两个小节。

2.1小节将详细介绍肯德尔趋势检验的概念、原理和相关背景知识。

我们将解释肯德尔趋势检验的基本原理和假设,并提供其计算公式和相关统计量的解释。

此外,我们还将介绍肯德尔趋势检验的一般步骤,以使读者了解如何进行该检验。

呼吸末二氧化碳(EtCO2)在被动抬腿实验(PLRT)中评估容量反应性的价值何怀武刘大为北京协和医院重症医学科容量反应性的评估是重症患者中容量管理的重要环节之一。

从心脏静态前负荷指标(CVP、PAWP、CREDVI、GEDVI等)到心脏动态前负荷指标(SPV、△down、PPV、SVV等)人们一直在寻找简单可靠并且敏感特异的指标或方法来预测容量反应性,进而减少扩容治疗的盲目性,提高扩容治疗的有效性。

其中在预测容量反应性方法上,被动抬腿试验(Passive Leg Raising Test,PLRT)具有可逆性、可重复性、操作简单及不需要额外增加容量等优点,并且不受自主呼吸和心律失常等因素的影响,在临床上实用性强。

近来Cavallaro等荟萃分析也支持PLRT作为预测容量反应性的方法具有良好准确性和可靠性[1]。

但目前PLRT在具体临床应用推广时也面临一些制约因素,近来有学者通过观察被动抬腿实验(PLRT)中呼末二氧化碳(EtCO2)的变化来评估容量反应性,进一步拓展了PLRT的临床应用价值。

一、PLRT评估容量反应性时存在的问题人为被动抬高患者下肢可起到类似自体输血的作用,可以快速地增加回心血量300mL ~500mL左右,曾作为失血性休克早期的抢救手段之一。

抬高下肢,在重力作用下,静脉回流增加,可起到快速扩容的效果,同时监测循环系统的反应来判断是否存在容量反应性。

被动抬腿试验相当于自体模拟的容量负荷试验,但由于受到自身神经系统的调节,其作用一般可维持10min左右,并且这种前负荷的扩增效应多在抬腿早期2-3min内最为明显[2]。

但目前PLRT在临床实践中面临的最大的问题是:抬腿后观察什么指标的变化来判断容量反应性?在理论上,被动抬腿增加心脏前负荷来检验心脏的储备能力,在此期间如能进行心输出量的直接观察和监测则最为理想,在监测技术上则要求能够实时同步监测心输出量或其替代指标的变化。

大量研究证实在被动抬腿期间,通过简单地观察心率,血压的变化,不能预测容量反应性。

国际酒店品牌初探——对喜来登酒店的相关调查与研究中山大学旅游管理目录1.喜来登发展历史 (4)1.1 大事记简图 (4)1.2国际发展历程 (5)1.3中国发展历程 (6)2.喜来登在世界范围内的发展 (7)2.1发展现状 (7)2.1.1 分布情况 (7)2.1.2酒店数量 (8)2.1.3主要产品 (9)2.1.4 品牌指数 (9)2.1.5电子服务 (10)2.2宏观环境分析 (10)2.2.1优势 (10)2.2.2劣势 (10)2.2.3机会 (11)2.2.4威胁 (11)2.3未来发展趋势 (12)3.喜来登中国发展现状与分析 (13)3.1喜来登在中国发展情况 (13)3.1.1喜来登全国分布 (15)3.1.2喜来登扩张情况 (16)3.1.3喜来登酒店房价与客房总数及其比较 (17)3.2、喜来登在中国发展的五力模型分析 (19)——以广州粤海喜来登酒店为例 (19)3.2.1供应商议价能力 (19)3.2.2购买者议价能力 (19)3.2.3潜在竞争者进入的能力 (20)3.2.4行业竞争者的竞争 (20)3.2.5替代品的威胁 (21)3.3基于网络评价的国内喜来登顾客感知研究 (22)3.3.1调查背景 (22)3.3.2研究过程 (22)3.3.3评价分析 (23)3.3.4酒店对顾客评价的回应 (24)3.4国内典型案例分析 (25)3.4.1.三亚的标杆现象 (25)3.4.2 湖州喜来登温泉度假酒店的“天价” (26)4.喜来登酒店的经营特点 (28)4.1喜来登的核心价值观 (28)4.2致力于打造高端品牌 (28)4.3多种营销相结合 (29)4.3.1 整合营销 (29)4.3.2关系营销 (29)4.3.3多渠道营销 (30)4.3.4电视节目营销 (30)4.4“以浮动价格调节市场”的定价策略 (30)4.5高服务质量 (31)4.6“融入自然”的建筑理念与特点 (33)5.喜来登酒店管理特点 (33)5.1企业文化 (33)5.1.1对“关爱文化”的概述 (34)5.1.2喜来登“关爱文化”典型案例 (34)5.2人力资源管理 (35)5.2.1中国喜来登酒店人力资源现状 (35)5.2.2典型案例——呼和浩特喜来登酒店 (35)5.3 员工培训 (36)5.3.1员工培训理念与模式 (36)5.3.2员工培训典型案例 (37)5.4跨文化管理 (37)5.4.1中美企业文化差异 (38)5.4.2中美员工的文化行为差异 (38)5.4.3典型案例分析——东莞喜来登酒店的跨文化管理现状 (39)5.5酒店设施的管理 (39)5.5.1基础设施改造 (40)5.5.2基础设施报废 (40)5.5.3基础设施档案管理 (40)6.参考文献 (41)1.喜来登发展历史1.1 大事记简图•喜来登品牌诞生1937•成为在纽约证券交易所挂牌的第一家连锁酒店1947•走上国际化的扩展之路1949•推出了行业内第一个自动化的电子预订系统的“预订系统”1958•以色列特拉维夫喜来登酒店开业,标志着喜来登进入中东地区1961•拉丁美洲的第一家喜来登酒店在委内瑞拉的马库图开业1963•喜来登第100 家酒店——波士顿喜来登酒店开门营业1965•大型跨国企业ITT 收购了喜来登连锁酒店1968•喜来登旗下已拥有165 家酒店,服务宾客超过1200 万人次,并雇有员工近2 万名1969•喜来登是第一家使用免费电话(1-800-325-3535) 直接为顾客提供服务的连锁酒店1970•喜来登在澳大利亚开设了亚太地区首家喜来登酒店1973•香港喜来登酒店正式开业1974•喜来登成为第一家在中华人民共和国开始运营的国际连锁酒店1986•喜达屋酒店与度假村国际集团收购了ITT 喜来登1998•SPG俱乐部取代了喜来登国际俱乐部1999•喜来登引入甜梦之床(Sweet Sleeper™ Bed)2004•采用Link@SheratonSM微软网吧2006•引入由Core® Performance 设计的喜来登健身计划20081.2国际发展历程1. 1937年,当时公司创始人 Ernest Henderson 和 Robert Moore 在马萨诸塞州春田市收购了他们的第三家酒店,并就此成立了全球知名品牌——喜来登。

阿尔茨海默病的研究进展梁子涌;武雅静;邓远飞【摘要】阿尔茨海默病(AD)是老年人常见的慢性进行性神经系统变性病,临床表现主要为记忆力减退、进行性认知功能衰退,伴有各种精神行为异常和人格改变,严重影响患者的生活质量,2012年WHO和ADI发表的报告“痴呆:一项公共卫生重点”指出,AD的发病率为770万人/年,每4秒新发一例痴呆.AD的病因尚未阐明,目前的治疗方法尚不能阻止或逆转AD的疾病发展,且近年来在新药物研发、新治疗方法探讨等方面都遇到了挫折,但是,关于AD的研究继续在深入,本文就AD在病因机制、诊断、辅助检查技术、治疗、预防等方面的新近研究进展作一综述.【期刊名称】《中国医药科学》【年(卷),期】2018(008)016【总页数】4页(P42-45)【关键词】阿尔茨海默病;诊断;β淀粉样蛋白;综述【作者】梁子涌;武雅静;邓远飞【作者单位】北京大学深圳医院,广东深圳518036;北京大学深圳医院,广东深圳518036;北京大学深圳医院,广东深圳518036【正文语种】中文【中图分类】R749.16阿尔茨海默病(Alzheimer’s disease,AD)是一种中枢神经系统退行性疾病,起病隐袭,病程呈慢性进行性,是老年期痴呆最常见的一种类型,随着疾病的进展,将严重影响社交、职业与生活功能,2012年WHO和ADI发表的报告“痴呆:一项公共卫生重点”指出,AD的发病率为770万人/年,每4秒新发一例痴呆,2010年全球的患者数达3560万,预计2030年达6570万,2050年达11540万[1]。

AD的病因尚未阐明,目前的治疗方法尚不能阻止或逆转AD的疾病发展,详细的病史采集与体检和精神状况检查对诊断至关重要,分子神经影像学指标和家族性基因突变可作为重要的支持证据。

本文将就AD在病因机制、诊断、辅助检查技术、治疗、预防等方面的新近研究进展作一浅述。

1 病因机制1.1 基因遗传学说AD最常见的是21号染色体的淀粉样前体蛋白(APP)基因,14号染色体的早老素1(PS1)基因及1号染色体的早老素2(PS2)基因[2],散发性AD的易感基因主要是19号染色体的载脂蛋白E(ApoE)基因 [3]。

报告中的信度与效度分析方法1. 信度分析方法1.1. 内部一致性信度分析内部一致性是指问卷中各个测量项之间的一致性程度。

常用的内部一致性信度分析方法包括Cronbach's alpha、检验无重复性原则和Kuder-Richardson等。

Cronbach's alpha是一种基于项目的测量信度分析方法,它通过计算测量项之间的方差协方差矩阵来评估问卷的内部一致性。

检验无重复性原则是通过将问卷中的某个测量项删除后,观察剩余的测量项之间的相互关联情况,来评估该测量项对于问卷的内部一致性的贡献程度。

Kuder-Richardson是一种基于二元测量项的信度分析方法,适用于只有两种回答选项的测量项。

1.2. 测试-重测信度分析测试-重测信度分析用于评估同一受试者在不同时点上的测量结果之间的一致性。

常用的方法包括Pearson相关系数、Spearman相关系数和Intraclass correlation coefficient(ICC)等。

Pearson相关系数和Spearman相关系数适用于连续变量的信度分析,而ICC适用于定量变量的信度分析。

1.3. 分裂信度分析分裂信度分析用于评估问卷中不同测量项的可靠性。

常用的方法包括Spearman-Brown公式和Guttman-Split Half方法等。

Spearman-Brown公式可以根据问卷的半数测试长度和全长测试长度之间的比例来估计问卷的信度。

Guttman-Split Half方法则将问卷分成两个部分,计算两部分的分数之间的相关系数,通过比较来评估问卷的信度。

2. 效度分析方法2.1. 内容效度分析内容效度分析用于评估问卷测量项是否涵盖了研究领域全部或者大部分的内容。

常用的方法包括专家评审法和适应性检测法等。

专家评审法是将问卷交给相关领域的专家进行评审,通过专家的意见来评估问卷的内容效度。

适应性检测法是根据问卷回答者的反馈来评估问卷的内容效度,通过观察回答者对于各个测量项的理解程度和回答行为来确定问卷的内容效度。

Advances in Psychology 心理学进展, 2015, 5(12), 805-810Published Online December 2015 in Hans. /journal/ap/10.12677/ap.2015.512104Antisocial Personality Disorder Concept and Clinical Research ProgressYue DuanSoochow University, Suzhou JiangsuReceived: Dec. 9th, 2015; accepted: Dec. 21st, 2015; published: Dec. 28th, 2015Copyright © 2015 by author and Hans Publishers Inc.This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY)./licenses/by/4.0/AbstractAntisocial personality disorder is a great danger to social security, which has always been the fo-cus of scholars at home and abroad. This article, through summarizing the diagnosis of antisocial personality, clinical and biological research both at home and abroad in recent years, discusses the problems existing in the present study, and looks forward to the future research direction.KeywordsAntisocial Personality Disorder, Diagnostic Tools, Clinical Research反社会人格障碍概念及研究进展段越苏州大学,江苏苏州收稿日期:2015年12月9日;录用日期:2015年12月21日;发布日期:2015年12月28日摘要反社会人格障碍是一种对社会危害极大的人格障碍,因此也一直是国内外学者关注的焦点,本文通过对近几年来国内外反社会人格的诊断、影响因素研究、生物学研究进展的总结,对目前研究中存在的问题段越进行讨论,并展望了未来的研究方向。

The Prostate Construction of Tissue Micro Array From Prostate Needle Biopsies Using theV ertical ClusteringRe-Arrangement T echniqueEduard Fridman,1*Dean Daya,1John Srigley,1Kaitlyn F.Whelan,2Jian-Ping Lu,2and Jehonathan H Pinthus21Department of Pathologyand Molecular Medicine,McMaster University,Hamilton,Ontario,Canada 2Department of Surgery,Division of Urology,McMaster University,Hamilton,Ontario,Canada BACKGROUND.Tissue microarray(TMA)allows for simultaneous rapid expression analysisof multiple molecular targets in many tissue specimens.TMA’s are specifically in demand forthe screening for diagnostic and prognostic markers in prostate cancer(PC).Consequently,TMAs from prostate needle biopsy(PNB)material taken at diagnosis before any treatmentcommenced are in demand.However,since PNB contain only limited amount of tumorarranged within a very thin tissue core,TMA construction from PNB is problematic.METHODS.Archival PNB from30PC patients with variable Gleason scores(6–10)and%ofcores involvement(30–90%)were used.Following selection of representative cores,the paraffinblocks were melted.Each core was sectioned into equal parts of3–4mm in length.For each case,a group of fragments was then re-embedded in a vertical ing Manual TMAApparatus,2mm cores from each of the vertically rearranged fragments were harvested.Sections(4m m)were stained with H&E and with high-molecular weight cytokeratin(HMWCK),PIN-cocktail(p63þp504S),and PSA immunohistochemical stains.RESULTS.A TMA from PNB with a capacity of80serial4m m sections was constructed.In allcases,identical tumor and neighboring tissue morphology(atrophic changes and high-gradeprostatic intra-epithelial neoplasia)with no loss of tissue was evident.CONCLUSIONS.The vertical clustering re-arrangement(VCR)technique is suitable for largescale construction of TMA blocks from PNB maintaining the morphological and immunohis-tochemical characteristics of the original samples.This method is promising both in terms ofarchival tissue preservation and biomarkers research.Prostate#2011Wiley-Liss,Inc.KEY WORDS:needle biopsy;prostate cancer;tissue microarrayI NTRODUCTIO NProstate cancer(PC)is a very heterogeneous tumor with a variable natural history.While a large number of tumors do not impose risk to the patient and can be followed closely[1],many require either radiation treatment or operative removal.Since therapy selection and treatment decisions are currently based on clinical parameters alone,there is a need for proper biomarkers that can define prognosis and response to therapy at diagnosis.To achieve that,many studies using highly sensitive genome-wide microarray have been con-ducted[2,3]and have highlighted some potential markers.However,as biomarkers,the value of these candidates should preferably be validated at the protein rather than the gene level.In addition,predic-tive markers should be tested on prostate biopsy material taken at diagnosis and before treatment rather Grant sponsor:Nash Family Foundation;Grant sponsor:Israeli Can-cer Society for their fellowship;Grant sponsor:Juravinski CancerCenter foundation.*Correspondence to:Eduard Fridman,MD,Department of Pathol-ogy,The Chaim Sheba Medical Center,Tel-Hashomer,Ramat-Gan, 52621Israel.E-mail:ef@.ilReceived26August2010;Accepted6January2011DOI10.1002/pros.21352Published online in Wiley Online Library ().ß2011Wiley-Liss,Inc.than retrospectively on radical prostatectomy (RP)specimens.Tissue microarray (TMA)technology is useful for profiling protein expression simultaneously in a large cohort of ing this technique avoids observer bias,provides standards for quality control and has the potential for high-throughput analysis.TMA may con-tain up to 500formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue cores that are organized into a new recipient block.Several studies have adopted this technique with tumor samples obtained from RP [4–6].Nevertheless,in contrast to the relatively large amount of material available from RP,prostate needle biopsies (PNB)con-tain only very limited amounts of tumor arranged within a very thin tissue core that limits the construc-tion of a TMA block.The tissue cores obtained are 15mm long but have a width of less than 1.26mm,which is the same as the outer diameter of the 18-G needle used in trans-rectal ultrasound guided (TRUS)prostate biopsies.Since they are embedded horizon-tally,obtaining a punch out cylindrical core to build the TMA will result in a very thin and unsuitable sample.Herein,we describe a methodology developed by us to construct a TMA from PNB which enables theproduction of up to 1004m m thick sections with pres-ervation of the original morphological and immuno-histochemical characteristics of the tumors.MA TERIALS ANDMETH ODS Patient Population and Tissue Collection Following study approval by the institutional Research Ethics Board (REB)on the condition that the patient’s identity (and therefore clinical data)remains confidential,PNB tissue samples from 30PC patients were taken from the archival material of the Department of Pathology at the Henderson Hospital in Hamilton,Ontario.All patients were subsequently treated by external beam radiation therapy as part of a clinical trial [7].Tumors were graded according to the current WHO/ISUP grading criteria [8].Gleason scores [9]were ranged from 6to 10with 30–90%of core involvement (Table I).Re-Embedding of theTissue Samples FromtheOriginal Donors’Blocks The original PNB paraffin blocks (Fig.1A)were melted (608C).Tissue cores were extracted and stained with eosin to better visualize the tissue.Each of these PNB tissue cores which typically measures 0.5mm in diameter,and 1.5cm in length (Fig.1A)was frag-mented with a scalpel to equal parts of 3–4mm in length (3–4parts of each core;Fig.1B).A cluster of 3–4fragments was then re-embedded in vertical orien-tation into new intermediate recipient paraffin block (Fig.1C).The intermediate block served as a template for correct vertical embedment of each cluster.Once that was verified,we use a manual TMA apparatus to harvest a core from this intermediate block and vertically embed it in the final TMA block according to pre-planned map (Fig.1D).T ABLE I.Gleason Pattern of the Study CasesGleason score Amount of patients %of Patients Score 61240%Score 7(3þ4)533.3%Score 7(4þ3)5Score 8310%Scores 9–105(3/5cases with ‘‘comedo’’necrosis and 1/5is neuro-endocrine carcinoma16.6%Fig.1.Principle phases of VCR-TMA construction.A :Donor block (original PNB core),(B )grouping of core fragments,(C )intermediate recipient paraffin block,(D )final TMA block.2Fridman et al.The ProstateConstruction of the Recipient BlockA new TMA block (final recipient block)was con-structed using the Beecher Instruments’Manual Tissue Microarray Apparatus (Silver Springs,MD),using a hollow needle of 2mm in diameter,harvesting a 2mm core composed from the vertically rearranged frag-ments of the original needle biopsy.Each core was inserted to the recipient block according to mapped plan (Fig.2).In addition to the patient’s PNB tissues,we used cores from other tissue types as negative internal controls (human clear cell renal cell carcinoma of the kidney,normal renal,lung,and hepatic tissue)and positive internal controls (prostatic adenocarcinoma sample from RP and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH)with foci of high-grade prostatic intra-epithelial neoplasia (Hg-PIN)from specimens taken during trans-urethral resection of prostate (TUR-P)).These samples were used not only as internal positive and negative controls for immunohistoche-mial staining,but also as landmarks for orientation in the process of the TMA block serial sectioning.Sectioning and Immuno-Staining of theTMARecipient BlockSectioning of the recipient TMA block (Fig.3)was done in a standard way (4m m)without damaging the quality of material (Fig.4).Immuno-staining was done with the following antibodies:Anti-high-molecular weight cytokeratin (HMWCK)antibody MA904(1/30Dakocytomation,Carpenteria,CA),Pin cocktail antibodies anti-AMACR and P63(1/75Zeta Corp,Sierra Madre,CA),and anti-PSA (1/10,000Dakocyto-mation).Immunostaining was performed using theLab Vision stainer (Fremont,CA)with incubation time of 35min for PSA and 55min for the other stainings.Visualization of the antigen/antibody reaction was performed using either a polymer (Invitrogen,Carls-bad,CA)or labeled streptavidin biotin detection sys-tem (Invitrogen)and diaminobenzidine (Sigma–Aldrich,Oakville,ON,Canada)as the chromagen.Negative control slides were performed by replace-ment of the primary antibody.RESUL TSTheV ertical Rearrangement of the Core FragmentsEnables Multiple Sectioning of an OriginallyThin PNB Core The initial width of the original core of PNB was approximately 1.26mm,which is the outer diameter of the 18-G needle used for TRUS guided prostate biop-sies.However the donor PNB cores used to construct the TMA block had diameters smaller than 0.5–0.6mm,because the original donor’s blocks (retrieved from the archive)were already trimmed and sectioned to pro-duce the diagnostic H&E slide which usually includes three levels.Often also,several more sections were used for the production of slides used for immunohis-tochemical staining during the diagnostic histological examination.The vertical positioning of the PNB core’s fragments changed the axis of the cores to allow up to 80serial 4m m sections.The outline of the vertically oriented cores is a good indication of a proper re-embedding procedure.Accordingly,an accurate ver-tical orientation of the cluster results in an incomplete circle shape of the core as one of the core sides has sharp edges (in the front of the originalhorizontallyFig.2.The final VCR-TMA‘‘recipient ’’blocks and slides.TheVCR final-ready to use TMA block is made from numerous different patients’tissue cores.Each cluster of core is inserted into a pre-plannedspot,according toX-andY -axiscoordinates.Ascanbeseen inthisfigure,after20serialsections,therecipientblockstillreserves sufficient tissue for additional 60^80sections.Fig.3.The outline of the vertically oriented cores serves as a good indication for proper re-embedding procedure.An accurate vertical orientation of the cluster results in an incomplete circle shape of the core.One side of the corehas sharp edges (blue arrow)while the opposite side is vaulted (brown arrow).The sharp edge results from previous sectioning of the superficial front of the original horizontally embedded donor core.Thevaulted edge main-tainstheoriginalcircular frontof thecoreinthedepthofdonor’spar-affin block.Prostate Needle BiopsyTissue Microarray3The Prostateembedded donor core that was previously sliced),and the opposite side remains vaulted preserving it’s original circular front faced in the depth of donor’s paraffin block (Fig.3).Instead,if an inaccurate vertical positioning of the cluster occurred,one would see various other forms of cutting surfaces.This can result in lower number of sections from the final TMA block that can be produced from those cases.Evidently,all the cores in our TMA blocks had a correct vertical orientation.Presence of this correct vertical orientation had granted us the ability to receive many serial sections.Assuming that the length of a perfectly oriented cluster of PNB cores was of 3–4mm in length,and the histological sections had 4m m thickness,then we could receive up to 80–100serial sections from the vertical clustering re-arrange-ment (VCR)TMA block.Accurate Selection of the Original Cores and Planning of Its Division and Fragments’OrientationResultsin the Presence of Cancerin AllSections of theV CR-TMA As demonstrated in Figure 5,selecting only original cores with at least 30%of cancer and exact frag-mentation of each core to allow their pre-planned ver-tical orientation are key technical elements that results in the presence of cancer tissue in each section of the TMA.Clustering of the Same Donor’s PNBFragments Increase the Area A vailable for Diagnostics Since we divided each 1.2–1.5mm originally hori-zontally oriented PNB core to equal 3–44mm core fragments and clustered them together before their vertical embedding,we actually produced a 2mm diameter of tissue for each case (including small inter-fragments space).This allowed sufficient tissue for analysis (Fig.4).Fig.4.Preservation of the original tissuemorphology(H&E)and staining characteristics in the final VCR-TMA.Low (A )and high magnification (B ).Areas of adenocarcinoma (arrow)arehighlighted bylacking of basal celllayer (HMWCKpositive cells)andprominent cytoplasmatic granular staining for the PIN-Cocktail staining.Residual benign glands (star)in these cores and in the control cores from the RP specimen (large round spot in A)are used as internal and external positive and negativecontrols.Fig.5.Accurate selection of the originalcores andplanningofits division and fragments’orientationresultsin thepresence of cancer in all sections of theVCR-TMA.Only cores with atleast 30%cancer (red)either in a single area (A ^D )or in several foci (E )should be selected.These cores are sectioned into 3^4fragments which are then grouped together and implanted vertically in a pre-planned map so thatineach sectionatleastonefragmentwillcontaincancer .We also recommend analyzing sections from both levels of the TMA (superficial and deep)to capture cancer .4Fridman et al.The ProstateThe Re-Arranged Coresin the Recipient TMABlock PreserveTheir Morphologicaland Immuno-StainingOriginal CharacteristicsFollowing very careful trimming until almost all of the cores appeared in the section,we started sectioning the block.Every tenth section was stained with H&E or immunohistochemical staining(PSA,HMWCK,PIN Cocktail{p63þAMACR})to verify the preservation of the tumor and surrounding characteristics.In the histological examination of all H&E stained sections, we found complete preservation of the sample’s morphological characteristics of the benign and malig-nant prostatic tissue(Table II),in both low and high magnification.For example the HMWCK(CK903) staining was positive in the basal cells of the benign prostatic glands and entirely negative in the malignant glands both in the original and final rearranged cores in all cases(Fig.4).The PIN-Cocktail staining (AMACRþP63)was positive in residual basal cells (nuclear pattern of staining)and positive in the malig-nant glands(granular cytoplasmic pattern of staining) both in the original and final rearranged cores in all cases(Fig.4).We found complete correlation between the primary Gleason pattern of the original PNM block and the final TMA in all cases.It should be noted however that in most samples in the final TMA block,the amount of cancer in each section was relatively small,which restricted our ability to determine both the primary and the secondary architectural patterns.Thus for each section we determined only the primary Gleason pat-tern.Notably the VCR-TMA contained also other histo-logical elements of prostatic pathologies and normal prostate such as prostatic intra epithelial neoplasia (PIN),atrophy,prostatic stroma,inflammation,and benign prostatic tissue-BPT(Table II).Thus the VCR-TMA maintains the heterogeneity of other pathological processes that co-exists in prostate biopsies.DISCUSSIO NTMA technology is central to the process of target and biomarker discovery for PC[10].To achieve this, the application of our method needs to be adapted to PC samples taken via TRUS guided PNB at the time of the initial diagnosis.Three other methods to construct TMA from PNB have been previously described in the literature by Jhavar et al.[11],which was later modified by McCarthy et al.[12],by Datta et al.[13]and by Singh et al.[14].These methods are relatively complicated necessitating multi-step construction of recipient block in a special mold.Unlike these reports our method is simple,rapid,and can be practice by common labora-tory personnel.In addition,the major advantage of our method over the others is that it minimizes the amount of tissue loss.Even though the length of core particles is usually3–4mm,by changing the orientation of the core fragments and regrouping them,we could obtain up to 804m m serial sections from each case.This vertical orientation is practically impossible using the method described by Jhavar et al.[11]as it is technically very difficult to precisely orient all the‘‘biopsy checkers’’described in their methodology in a vertical and paral-lel position to each other(while keeping the mapping order).These fragments tend to move while being embedded and may be finally located in a different position than the mapping plan.Also Jhavar et al.[11] noticed9%of sample loss(4out of45samples from23 patients).Significant percentage of tissue loss was also reported by Singh et al.[14]who used a standard TMA approach.Accordingly we believe that tissue loss can be minimized by applying a correct vertical orientation of regrouped core fragments.This is feasible using the VCR method as the embedding of the core cluster into the TMA paraffin block is done using a standard2mm TMA apparatus.Thus our method is preferable when a smaller diameter of needle core is available.In the VCR technique one can precisely control the quality of the vertical orientation(Fig.3):Grouping of 2–3parts of a single core in one location prevents the loss of tissue from each cylinder,as at least one of these parts would be present in the serial sections after the trimming of the TMA block.Most importantly,cluster-ing of the core fragments allows a significant increase in (2–3times)the area of research as compared to the single core structure as proposed by Jhavar et al.[11].This is a very critical point in the field of PC research as one of the characteristics of cancerous glands is the spread and infiltration of cancerous cells between the residual benign prostatic glands. Therefore,the widely available research surface sig-nificantly increases the chance of capturing tumor glands in the serial sections from recipient TMA blocks. Finally,in contrast to Jhavar et al.[11]who could only insert45samples in each paraffin block with standard dimensions,our technique allows up to70different samples to be embedded in the same size block(55% increase).In another method to construct TMA from PNB described by Datta et al.[13],parts of prostatic tissue cores that contained PC were cut out from the original block.These parts were re-embedded in paraffin in a complex multi-step technical procedure using additional materials(Rubber blocks,aluminum foil). Only then,the latter paraffin cores were inserted using tweezers to a pre-prepared TMA recipient block.This method also applied the vertical placement of the cores in the TMA block.However,as opposed to this technique described by Datta et al.[13],the VCR tech-nique does not require any additional materials or Prostate Needle BiopsyTissue Microarray5The ProstateT ABLE II.TheV CR-TMACaptures Myriad Histological FindingsThat are Characterized in Prostate BiopsiesCluster%of Cancer%of Stromal tissue%of PIN%of AtrophyPresence ofinflammation[18]%of BPT18020——À—29010——À—3100———À—43040—30À—58020——À—6955——À—75050——À—85050——À—9403030—À—10306010—À—11100———À—12—603010À—13100———À—14100———À—1580———À20 1680———À20 17801010—À—188020——þ—19702010—À—20———100À—218020——À—228020——À—2380———À20 24100———À—2570———À30 26100———À—277030——À—28100———À—29100———À—30100(NE)———À—31—8020—À—3250———À50 33100———À—34100———À—3550——50þ—36100———À—378020——À—38100———À—399010——À—40801010—À—4130——70À—4230——70À—4380———À20 44100———À—45304030—þ—46100———À—4770——30À—48———100þ—4950——50þ—50100———À—51100———À—5250——50À—538020——À—(Continued) 6Fridman et al.The Prostateinstruments to the ones found in any histological laboratory and the TMA apparatus.Importantly,the VCR method enables the usage of prostate tissue cores in which the tumor is multi-focal and is not only present in one continuous area(Fig.5E). This substantially increases the amount of cases that can be integrated into the TMA.The clustering organ-ization of the prostatic tissue cores in our method significantly increases the available research area as compared to the method proposed by Datta et al.[13].Since our technique involves division of the donor core,it results in sampling of both the malignant and the benign prostate tissue from the same patient in one cluster.This creates a‘‘built-in’’internal control in the TMA block(Table II).The VCR technique also maxi-mizes the number of4m m serial sections that can be obtained from each TMA block.This is due to the uniform depth and the standard even core parts dimen-sions that are embedded.However,in order to save material(by avoiding re-trimming)we suggest per-forming all serial sections of the block at once,with an accurate numbering by the order of slides.We also recommend that the sections should be preserved unstained and dry in the dark inÀ48C in a special box.Of note,for optimal results it is preferable that those in which only a single core is present are used as donor blocks.This is consistent with previous recom-mendations[15,16]because when multiple cores are embedded in the same paraffin block the tissue loss during processing is more prominent[17].Finally,to avoid complete disruption of all the original material we recommend selecting only one or two original cores from each case leaving some original carcinoma containing cores(original blocks) in the archive.Nevertheless,we can foresee in the future a role for the VCR-TMA as a compact way to store prostate biopsy samples(libraries),particularly as the arrangement of the samples in the TMA can be linked to the patient’s dataset including the documen-tation of the original pathological diagnosis.CO NCL USIO NSThe VCR technique converts a minimal amount of archival horizontally positioned PNB tissue core into a TMA block.Dividing the original needle core tissue into several parts widens the research area so that each case is represented with a relatively wide transverse diameter.The vertical orientation of the cores maxi-mizes the number of4m m serial sections(up to80) available for research and diagnostic purposes.This method can facilitate PC biomarker research and assist in the archival tissue preservation of the growing amount of PNB cases.ACKN O WLEDGMENTSWe are indebted to the Nash Family Foundation and the Israeli Cancer Society for their fellowship grant support(Dr.Fridman)and to the Juravinski Cancer Center foundation grant support(Dr.Pinthus)used in this study.REFERENCES1.Dall’Era MA,Cooperberg MR,Chan JM,Davies BJ,AlbertsenPC,Klotz LH,Warlick CA,Holmberg L,Bailey DE,Jr,Wallace ME,Kantoff PW,Carroll PR.Active surveillance for early-stage prostate cancer:Review of the current literature.Cancer 2008;112:1650–1659.2.Grouse LH,Munson PJ,Nelson PS.Sequence databases andmicroarrays as tools for identifying prostate cancer biomarkers.Urology2001;57:154–159.3.Nakagawa T,Kollmeyer TM,Morlan BW,Anderson SK,Berg-stralh EJ,Davis BJ,Asmann YW,Klee GG,Ballman KV,Jenkins RB.A tissue biomarker panel predicting systemic progression after PSA recurrence post-definitive prostate cancer therapy.PLoS One2008;3:e2318.T ABLEII.(Continued)Cluster%of Cancer%of Stromal tissue%of PIN%of AtrophyPresence ofinflammation[18]%of BPT5450——50À—5550——50À—56100———À—5780——20À—58100———À—5940—2040À—60———100À—618020——À—6260——40þ—638020——þ—6480——20þ—Prostate Needle BiopsyTissue Microarray7 The Prostate4.Titus MA,Gregory CW,Ford OH III,Schell MJ,Maygarden SJ,Mohler JL.Steroid5alpha-reductase isozymes I and II in recur-rent prostate cancer.Clin Cancer Res2005;11:4365–4371.5.Garraway IP,Seligson D,Said J,Horvath S,Reiter RE.Trefoilfactor3is overexpressed in human prostate cancer.Prostate 2004;61:209–214.6.Hofer MD,Kuefer R,Varambally S,Li H,Ma J,Shapiro GI,Gschwend JE,Hautmann RE,Sanda MG,Giehl K,Menke A, Chinnaiyan AM,Rubin MA.The role of metastasis-associated protein1in prostate cancer progression.Cancer Res2004;64:825–829.7.Lukka H,Hayter C,Julian JA,Warde P,Morris WJ,Gospodarowicz M,Levine M,Sathya J,Choo R,Prichard H, Brundage M,Kwan W.Randomized trial comparing two fractionation schedules for patients with localized prostate cancer.J Clin Oncol2005;23:6132–6138.PubMed PMID: 16135479.8.Epstein JI,Allsbrook WC,Jr Amin MB,Egevad LL,ISUP GradingCommittee.The2005International Society of Urological Path-ology(ISUP)Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma.Am J Surg Pathol2005;29:1228–1242.9.Gleason DF.Histologic grade,clinical stage,and patient age inprostate cancer.NCI Monogr1988;(7):15–18.10.Rubin MA,Zhou M,Dhanasekaran SM,Varambally S,BarretteTR,Sanda MG,Pienta KJ,Ghosh D,Chinnaiyan AM.Alpha-methylacyl coenzyme A racemase as a tissue biomarker for prostate cancer.JAMA2002;287:1662–1670.11.Jhavar S,Corbishley CM,Dearnaley D,Fisher C,Falconer A,Parker C,Eeles R,Cooper CS.Construction of tissue microarraysfrom prostate needle biopsy specimens.Br J Cancer2005;93:478–482.12.McCarthy F,Fletcher A,Dennis N,Cummings C,O’Donnell H,Clark J,Flohr P,Vergis R,Jhavar S,Parker C,Cooper CS.An improved method for constructing tissue microarrays from prostate needle biopsy specimens.J Clin Pathol2009;62:694–698.13.Datta MW,Kahler A,Macias V,Brodzeller T,Kajdacsy-Balla A.A simple inexpensive method for the production of tissue micro-arrays from needle biopsy specimens:Examples with prostate cancer.Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol2005;13:96–103.14.Singh SS,Mehedint DC,Ford OH III,Maygarden SJ,Ruiz B,Mohler JL.Feasibility of constructing tissue microarrays from diagnostic prostate biopsies.Prostate2007;67:1011–1018.PubMed PMID:17476688.15.Amin M,Boccon-Gibod L,Egevad L,Epstein JI,Humphrey PA,Mikuz G,Newling D,Nilsson S,Sakr W,Srigley JR,Wheeler TM, Montironi R.Prognostic and predictive factors and reporting of prostate carcinoma in prostate needle biopsy specimens.Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl2005;216:20–33.16.Boccon-Gibod L,van der Kwast TH,Montironi R,Boccon-GibodL,Bono A.Handling and pathology reporting of prostate biop-sies.Eur Urol2004;46:177–181.17.Kao J,Upton M,Zhang P,Rosen S.Individual prostate biopsycore embedding facilitates maximal tissue representation.J Urol 2002;168:496–499.18.Nickel JC,True LD,Krieger JN,Berger RE,Boag AH,Young ID.Consensus development of a histopathological classification system for chronic prostatic inflammation.BJU Int2001;87: 797–805.8Fridman et al. The Prostate。

科技的不断发展,深深改变了传统的商业模式。

基于物品交换的供应链模式已经逐渐被淘汰,随着互联网用户的不断增多,越来越多的人开始“触网”,同时也在网上留下了大量数据,比如浏览记录,购买记录,出行记录等。

数据的不断积累,为商业变革打下了基础。

而大数据技术的浮现,则点燃了商业变革的导火索。

越来越多的企业通过大数据分析技术重塑商业模式,进行服务创新。

商业策略这一概念,最早是由BCG 的创始人布鲁斯亨德森和哈佛大学商学院的教授迈克尔波特提出。

亨德森理论的核心是集中优势力量对付敌人的弱点,他认为,在商业领域,包含许多被经济学家成为报酬递增的现象,比如:产业规模,投入越大,产出越大。

波特认可这一理论,但是也提出来一些限制性理论,他指出,亨德森的理论的确成立,但是从商业上来说,需要更多的步骤,一个公司或者经济模式可能在一些活动中占有优势,但可能并不合用于其他活动。

他提出来“价值链”这一概念。

基于亨德森和波特的理论,整个商业策略大厦逐渐建立起来。

但是在大数据时代,这一理论已经不在成立。

随着互联网技术的发展,信息的获取变得十分便捷,交易成本在不断降低。

交易成本的下降,导致可利用资源减少了,对垂直机构的整合也就会随之减少,价值链也会随之断裂,也可能不会断裂,但是对于同一商业中的竞争者来说,他们就可能利用其在价值链的位置,以此对竞争对手进行渗透、攻击。

英国出版的百科全书曾经是世界上最畅销的书籍之一,随着光盘和网络的流行,知识传播和更新的成本在不断下降,百科书行业随之倒闭。

维基百科随之兴起,和百科全书不同的是,维基百科的内容是由用户撰写的,并且非常专业,价格也非常便宜。

再比如2000 年,人类基因图谱的绘制,主要由专业的科研机构和科学家完成,耗费了2 亿美金和10 年的时间,才绘制出一个人的基因图谱。

而现在只需要不到1000 美元,甚至立等可取,这个行业甚至成为了零售业,以后当你去看医生的时候,可能会被要求先做一个基因绘制,然后医生会根据基因信息,找出致病基因,给你开出基因药物。

波士顿经验曲线简介波士顿经验曲线又称经验学习曲线、改善曲线。

经验曲线是一种表示生产单位时间与连续生产单位之间的关系曲线。

学习曲线效应及与其密切相关的经验曲线效应表示了经验与效率之间的关系。

当个体或组织在一项任务中习得更多的经验,他们会变得效率更高。

这两个概念出自英语谚语:“实践出真知”。

1960年,波士顿咨询公司(Boston Consulting Group)的布鲁斯·亨德森(Bruce D. Henderson)首先提出了经验曲线效应(Experience Curve Effect)。

亨得森发现生产成本和总累计产量之间存有一致相关性。

简而言之,就是如果一项生产任务被多次反复执行,它的生产成本将会随之降低。

每一次当产量倍增的时候,代价值(包括管理、营销、分销和制造费用等)将以一个恒定的、可测的比率下降。

此后,研究人员对各个行业的经验曲线效应进行了研究,发现下降的比率在10%至30%之间。

波士顿经验曲线图例经验曲线是一个人们较为熟知的概念。

一家工厂生产某种产品的数量越多,生产者就能更多地了解了如何生产该产品,从生产中获得的经验也就越来越多。

那么,在以后的生产中,工厂可以有目的地并且较为准确地减少该产品的生产成本。

每当工厂的累积产量增大一倍时,其生产成本就可以降低一定的百分比(该百分比的具体大小因行业不同而有所差别)。

下图表明在生产某产品的过程中,90%的经验曲线是如何对生产成本产生影响的。

学习曲线效应(The learning curve effect)指的是越是经常地执行一项任务,每次所需的时间就越少。

这个关系最初在1925年在美国怀特-彼得森空军基地量化,使得航空效率加倍而所需劳动时间下降了10-15%。

随后在其它行业的经验研究得出了不同值:从百分之几到百分之三十。

但在大多数情况下这是一个常量值:它不随行为规模的变化而变化。

学习曲线将学习效果数量化绘制于坐标纸上,横轴代表练习次数(或产量),纵轴代表学习的效果(单位产品所耗时间),这样绘制出的一条曲线,就是学习曲线。

Brandford法检测蛋白质含量实验原理考马斯亮兰G-250染料,有红、蓝两种不同颜色的形式。

在酸性条件下可配成淡红色的溶液,当与蛋白质结合后,产生蓝色化合物,反应迅速而稳定。

反应化合物在465nm 〜595nm处有最大的光吸收值,化合物颜色的深浅与蛋白浓度的高低成正比关系,因此可检测595nm的吸光度值,计算蛋白的含量。

二仪器和试剂1.仪器:分光光度计、移液抢、具塞刻度试管、烧杯、量瓶、研钵2.试剂:考马斯亮蓝G-250染料、牛血清蛋白、90%乙醇、85%磷酸考马斯亮蓝G-250:称取100mg考马斯亮蓝,溶于50ml90%L醇中,加入100ml85% 的磷酸,再用蒸馏水定溶到1L,贮于棕色瓶中。

标准牛血清蛋白溶液:100ug/ml牛血清蛋白:称取牛血清蛋白25ml加水溶解并定溶至100ml,吸取上述溶液40ml,用蒸馏水稀释至100ml即可。

三实验步骤1.标准曲线的绘制取6支试管,按下表加入试剂(0〜100ug/ml的标准蛋白)。

混合均匀后,向各管中加入5ml考马斯亮蓝溶液,摇匀,并放置5min左右,用1cm光径的比色皿在595nm下比色测定吸光度。

以蛋白质浓度为横坐标,以吸光度为纵坐标绘制标准曲线。

绘制标准曲线的各试剂加入量2.样品的测定(1)样品的提取:称取鲜样0.25-0.5g,用5ml缓冲液研磨成匀浆后,3000r/min 离心10min,取上清液1.0ml (视蛋白质含量适当稀释)于试管中(每个样品重复2次)。

(2)加入5ml考马斯亮蓝溶液,充分混合,放置2min后在595nm下比色,测定吸光度,并通过标准曲线查得蛋白质含量。

四、结果计算C m V样品中蛋白质含量 = ----- T (mg/g)V S XW F^OOO式中:c—查标曲值;VT—提取液总体积;W—样品鲜重;VS-测定时加样量,ml。

羊塔1气藏生产动态资料判断水侵模式方法郭珍珍;李治平;杨志浩;张航;李梅【摘要】气井出水严重影响气井正常生产,分析气井产水来源和水侵模式是开发后期调整开发方案的基础和依据.以羊塔1气藏为例,提出判断气藏水侵模式的方法.首先用产出水矿化度判断产出水来源,再利用含气饱和度、产液剖面、试井结果等生产动态资料分析气藏水侵模式,判断出羊塔1气藏水侵模式为边水推进、底水绕进的复合模式.运用数值模拟对比验证,得到的判断结果与其保持一致.该方法分析过程简单,结果准确,为以后分析复杂气藏产水模式提供了依据.【期刊名称】《科学技术与工程》【年(卷),期】2015(015)001【总页数】5页(P206-209,214)【关键词】生产动态资料;水侵模式;数值模拟【作者】郭珍珍;李治平;杨志浩;张航;李梅【作者单位】中国地质大学(北京)非常规天然气能源地质评价与开发工程北京市重点实验室,能源学院,北京100083;中国地质大学(北京)非常规天然气能源地质评价与开发工程北京市重点实验室,能源学院,北京100083;中国地质大学(北京)非常规天然气能源地质评价与开发工程北京市重点实验室,能源学院,北京100083;中国地质大学(北京)非常规天然气能源地质评价与开发工程北京市重点实验室,能源学院,北京100083;中国地质大学(北京)非常规天然气能源地质评价与开发工程北京市重点实验室,能源学院,北京100083【正文语种】中文【中图分类】TE332目前我国许多气藏在开发过程中都面临着气井出水问题,严重影响到气井正常生产。

产水气井水侵来源判断是气田进行后期开发调整的基础,也是制定后期开发调整的依据。

英买力气田投产5年来,见水井超过总井数的50%。

2012年4月气田群综合含水达到16.62%。

该气田气井出水类型较多,不同区块的见水井产水模式不同,必须尽快搞清气井产水原因、水侵来源和途径,才能及时提出合理的生产技术对策,缓解生产中水侵带来的危害。