Synopses

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:60.88 KB

- 文档页数:7

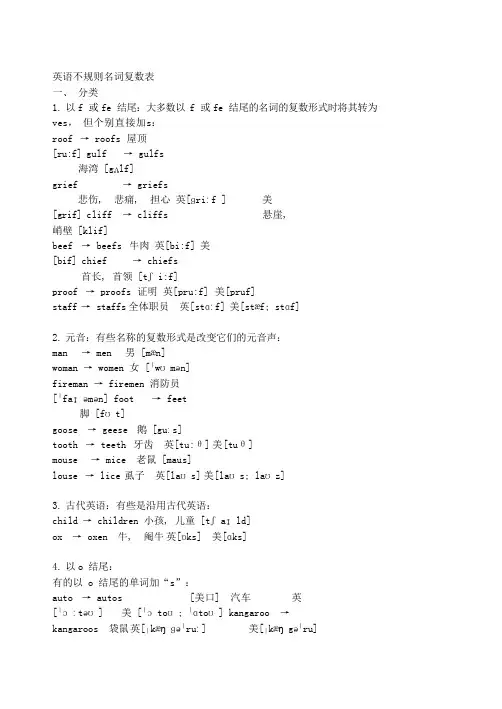

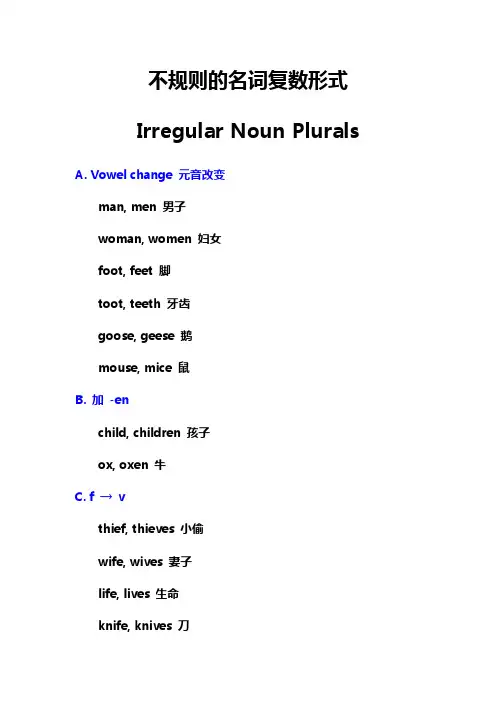

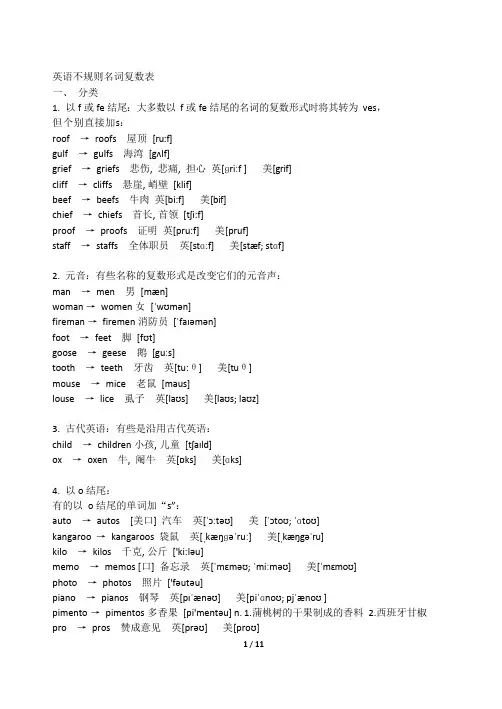

英语不规则名词复数表一、分类1.以f 或fe 结尾:大多数以 f 或 fe 结尾的名词的复数形式时将其转为ves,但个别直接加s:roof → roofs 屋顶[ru:f] gulf → gulfs海湾 [gʌlf]grief → griefs悲伤, 悲痛, 担心英[ɡriːf ] 美[grif] cliff → cliffs 悬崖,峭壁 [klif]beef → beefs 牛肉英[bi:f] 美[bif] chief → chiefs首长, 首领 [tʃi:f]proof → proofs 证明英[pru:f] 美[pruf]staff → staffs 全体职员英[stɑːf] 美[stæf; stɑf]2.元音:有些名称的复数形式是改变它们的元音声:man → men 男[mæn]woman → women 女 [ˈwʊmən]fireman → firemen 消防员[ˈfaɪəmən] foot → feet脚 [fʊt]goose → geese 鹅 [guːs]tooth → teeth 牙齿英[tu:θ] 美[tuθ]mouse → mice 老鼠 [maus]louse → lice 虱子英[laʊs] 美[laʊs; laʊz]3.古代英语:有些是沿用古代英语:child → children 小孩, 儿童 [tʃaɪld]ox → oxen 牛, 阉牛英[ɒks] 美[ɑks]4.以o 结尾:有的以 o 结尾的单词加“s”:auto → autos [美口] 汽车英[ˈɔːtəʊ] 美 [ˈɔtoʊ; ˈɑtoʊ] kangaroo →kangaroos 袋鼠英[ˌkæŋɡəˈruː] 美[ˌkæŋgəˈru]kilo → kilos 千克, 公斤 ['ki:ləu]memo → memos [口] 备忘录英[ˈmɛməʊ; ˈmiːməʊ] 美[ˈmɛmoʊ] photo → photos 照片 ['fəutəu]piano → pianos 钢琴英[pɪˈænəʊ] 美[piˈɑnoʊ; pjˈænoʊ ]pimento → pimentos 多香果 [pi'mentəu] n. 1.蒲桃树的干果制成的香料 2.西班牙甘椒pro → pros 赞成意见英[prəʊ] 美[proʊ]con → cons 反对意见英[kɒn] 美[kɑn]solo → solos, soli 独唱, 独奏英[ˈsəʊləʊ]美 [ˈsoʊloʊ] soprano → sopranos 女高音英[səˈprɑːnəʊ] 美[səˈprænoʊ]studio → studios 工作室英[ˈstjuːdɪˌəʊ]美[ˈstudiˌoʊ; ˈstjudioʊ] tattoo → tattoos 文身英[tæˈtuː] 美[tæˈtu]video → videos 视频英[ˈvɪdɪˌəʊ] 美[ˈvɪdiˌoʊ] zoo → zoos动物园英[zuː] 美[zu]bamboo → bamboos 竹子[bæm'bu:]radio → radios 收音机英[ˈreɪdɪəʊ]美[ˈreɪdiˌoʊ] mulatto→ mulattos 白黑混血儿[mju'lætəu]有的则加“es”:echo → echoes 回声, 反响英[ˈɛkəʊ] 美[ˈɛkoʊ]embargo → embargoes 禁运, 禁运令英[ɛmˈbɑːɡəʊ]美[ɛmˈbɑrgoʊ; ɪmˈbɑrgoʊ] hero → heroes 英雄英['hiərəu] 美['hɪro]potato → potatoes 土豆英[pəˈteɪtəʊ] 美[pəˈteɪtoʊ; pəˈteɪtə] tomato → tomatoes 番茄英[tə'mɑ:təu] 美 [tə'meitəu] torpedo →torpedoes 鱼雷, 水雷英[tɔːˈpiːdəʊ] 美[tɔrˈpidoʊ] veto → vetoes 否决, 否决权['vi:təu]negro → negroes 黑人英[ˈniːgrəʊ]美[ˈnigroʊ] jingo → jingoes 侵略主义,沙文主义['dʒingəu]mango → mangoes 芒果英[ˈmæŋɡəʊ] 美[ˈmæŋgoʊ]有的两种都可以:buffalo → buffalos / buffaloes / buffalo 水牛英[ˈbʌfəˌləʊ] 美[ˈbʌfəˌloʊ] cargo → cargos / cargoes (船/飞机的)货物英[ˈkɑːɡəʊ] 美 [ˈkɑrgoʊ] halo → halos / haloes 光环英[ˈheɪləʊ]美[ˈheɪloʊ]mosquito → mosquitos / mosquitoes 蚊子[məs'ki:təu] motto → mottos/ mottoes 箴言, 格言['mɔtəu]no → nos / noes 没有英[nəʊ] 美[noʊ]tornado → tornados / tornadoes 龙卷风英[tɔːˈneɪdəʊ]美 [tɔrˈneɪdoʊ] volcano → volcanos / volcanoes 火山英[vɒlˈkeɪnəʊ] 美[vɑlˈkeɪnoʊ;vɔlˈkeɪnoʊ] zero → zeros / zeroes 零英[ˈzɪərəʊ] 美[ˈzɪroʊ; ˈziroʊ]commando → commands / commandoes 突击员英[kəˈmɑːndəʊ] 美[kəˈmændoʊ; kəˈmɑ ndoʊ ]5.不变:有的则不变:cod → cod 鳕鱼英[kɒd] 美[kɑd]deer → deer 鹿[diə]fish → fish 鱼, 鱼类[fɪʃ]offspring → offspring 子孙, 后裔, 幼崽英['ɔ:fspriŋ] 美['ɔf,sprɪŋ] perch → perch鲈鱼英[pɜːtʃ] 美[pɜrtʃ]sheep → sheep 绵羊英[ʃiːp] 美[ʃip] trout → trou 鲑鱼 [traʊt]bison → bison 野牛 ['baisn]moose → moose 驼鹿英[muːs] 美[mus]aircraft → aircraft 飞机, 飞行器英[ˈɛəˌkrɑːft] 美[ˈɛrˌkræft] barracks→ barracks 兵营 [ˈbærəks]crossroads → crossroads 十字路口英[ˈkrɒsˌrəʊdz] 美[ˈkrɔsˌroʊdz] dice → dice骰子 [dais]gallows → gallows 绞刑架['gæləuz]headquarters → headquarters 总部英[ˌhɛdˈkwɔːtəz]美[ˈhɛdˌkwɔrtərz] means → means 方法, 手段, 途径英[miːnz] 美[minz]series → series 系列英[ˈsɪəriːz]美[ˈsɪriz] species → species物种['spi:ʃiz]6.借用单词:英语中有些单词是借用其他语言的。

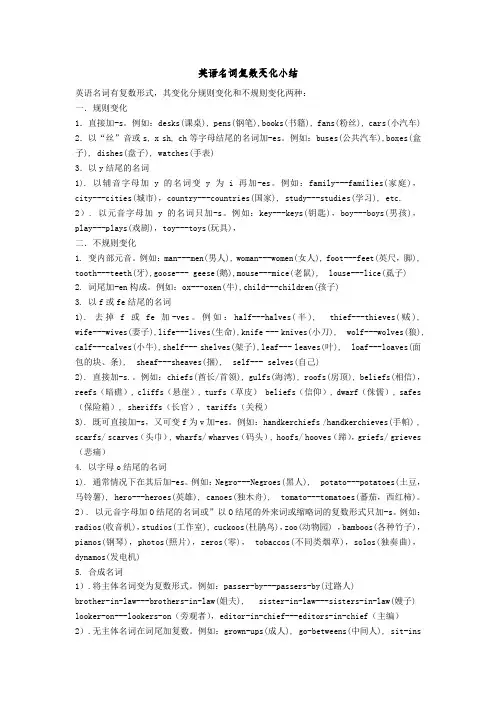

英语名词复数变化小结英语名词有复数形式,其变化分规则变化和不规则变化两种:一.规则变化1.直接加-s。

例如:desks(课桌), pens(钢笔),books(书籍), fans(粉丝), cars(小汽车) 2.以“丝”音或s, x sh, ch等字母结尾的名词加-es。

例如:buses(公共汽车),boxes(盒子), dishes(盘子), watches(手表)3.以y结尾的名词1). 以辅音字母加y的名词变y为i再加-es。

例如:family---families(家庭),city---cities(城市),country---countries(国家), study---studies(学习), etc. 2). 以元音字母加y的名词只加-s。

例如:key---keys(钥匙),boy---boys(男孩),play---plays(戏剧),toy---toys(玩具),二.不规则变化1. 变内部元音。

例如:man---men(男人), woman---women(女人), foot---feet(英尺,脚), tooth---teeth(牙),goose--- geese(鹅),mouse---mice(老鼠), louse---lice(虱子)2. 词尾加-en构成。

例如:ox---oxen(牛),child---children(孩子)3. 以f或fe结尾的名词1). 去掉f或fe加-ves。

例如:half---halves(半),thief---thieves(贼), wife---wives(妻子),life---lives(生命),knife --- knives(小刀), wolf---wolves(狼), calf---calves(小牛),shelf--- shelves(架子),leaf--- leaves(叶), loaf---loaves(面包的块、条), sheaf---sheaves(捆), self--- selves(自己)2). 直接加-s.。

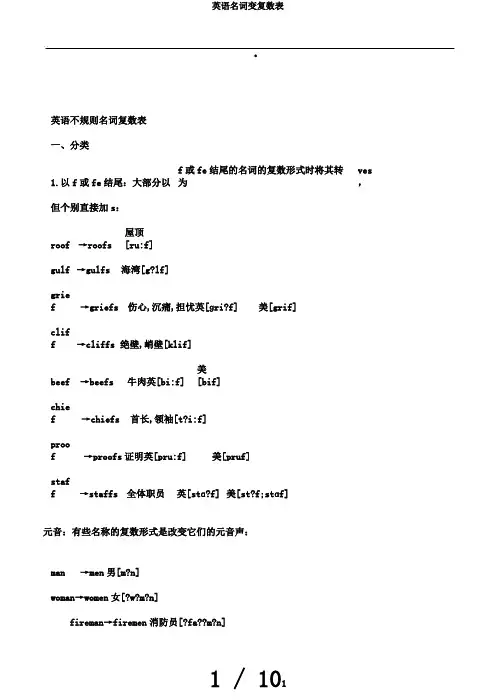

.英语不规则名词复数表一、分类1.以f或fe结尾:大部分以f或fe结尾的名词的复数形式时将其转为ves,但个别直接加s:roof→roofs 屋顶[ru:f]gulf→gulfs海湾[g?lf]grief→griefs伤心,沉痛,担忧英[ɡri?f]美[grif]cliff→cliffs绝壁,峭壁[klif]beef→beefs牛肉英[bi:f]美[bif]chief→chiefs首长,领袖[t?i:f]proof→proofs证明英[pru:f]美[pruf]staff→staffs全体职员英[stɑ?f]美[st?f;stɑf]元音:有些名称的复数形式是改变它们的元音声:man→men男[m?n]woman→women女[?w?m?n]fireman→firemen消防员[?fa??m?n]foot→feet脚[f?t]goose→geese鹅[gu?s]tooth→teeth牙齿英[tu:θ]美[tuθ] mouse→mice老鼠[maus]louse→lice虱子英[la?s]美[la?s;la?z]古代英语:有些是沿用古代英语:child →children小孩,小孩[t?a?ld] ox →oxen牛,阉牛英[?ks] 美[ɑks]以o结尾:有的以o结尾的单词加“s”:auto→autos [美口]汽车英[???t??]美[??to?;?ɑto?]kangaroo→kangaroos袋鼠英[?k??ɡ??ru?]美[?k??g??ru] kilo→kilos千克,公斤['ki:l?u]memo→memos[口]备忘录英[?m?m??;?mi?m??]美[?m?mo?] photo→photos照片['f?ut?u]piano→pianos钢琴英[p??n??]美[pi?ɑno?;pj??no?]pimento→pimentos多香果[pi'ment?u]n.1.蒲桃树的干果制成的香料2.西班牙甘椒pro→pros同意建议英[pr??]美[pro?] ..con→cons反对建议英[k?n]美[kɑn]solo→solos,soli独唱,独奏英[?s??l??]美[?so?lo?]soprano→sopranos女高音英[s??prɑ?n??]美[s??pr?no?]studio→studios工作室英[?stju?d????]美[?studi?o?;?stjudio?]tattoo→tattoos文身英[t??tu?]美[t??tu]video→videos 视频英[?v?d????]美[?v?di?o?]zoo→zoos动物园英[zu?]美[zu]bamboo→bamboos竹子[b?m'bu:]radio→radios收音机英[?re?d???]美[?re?di?o?]mulatto→mulattos白黑混血儿[mju'l?t?u]有的则加“es”:echo→echoes回声,反应英[??k??]美[??ko?]embargo→embargoes禁运,禁运令英[?m?bɑ?ɡ??]美[?m?bɑrgo?;?m?bɑrgo?]hero→heroes英豪英['hi?r?u]美['h?ro]potato→potatoes 土豆英[p??te?t??]美[p??te?to?;p??te?t?]tomato→tomatoes番茄英[t?'mɑ:t?u]美[t?'meit?u]torpedo→torpedoes鱼雷,水雷英[t???pi?d??]美[t?r?pido?]veto→vetoes反对,反对权['vi:t?u]negro→negroes黑人英[?ni?gr??]美[?nigro?]jingo→jingoes侵略主义,沙文主义['d?ing? u]mango→mangoes芒果英[?m??ɡ??]美[?m??go?]有的两种都能够:buffalo→buffalos/buffaloes/buffalo水牛英[?b?f??l??]美[?b?f??lo?]cargo→cargos/cargoes(船/飞机的)货物英[?kɑ?ɡ??]美[?kɑrgo?]halo→halos/haloes光环英[?he?l??]美[?he?lo?]mosquito→mosquitos/mosquitoes蚊子[m?s'ki:t?u] motto→mottos/mottoes箴言,格言['m?t?u] no→nos/noes没有英[n??]美[no?]tornado→tornados/tornadoes龙卷风英[t???ne?d??]美[t?r?ne?do?]volcano→volcanos/volcanoes火山英[v?l?ke?n??]美[vɑl?ke?no?;v?l?ke?no?]zero→zeros/zeroes零英[?z??r??]美[?z?ro?;?ziro?]commando→commands/commandoes突击员英[k??mɑ?nd??]美[k??m?ndo?;k??mɑndo?]5.不变:有的则不变:..cod→cod鳕鱼英[k?d]美[kɑd]deer→deer鹿[di?]fish→fish鱼,鱼类[f??]offspring→offspring后代,后代,幼崽英['?:fspri?]美['?f,spr??]perch→perch鲈鱼英[p??t?]美[p?rt?]sheep→sheep绵羊英[?i?p]美[?ip] trout→trou鲑鱼[tra?t]bison→bison野牛['baisn]moose→moose驼鹿英[mu?s]美[mus]aircr aft →aircraft飞机,飞翔器英[????krɑ?ft]美[??r?kr?ft]barracks→barracks军营[?b?r?ks]crossroads→crossroads十字路口英[?kr?s?r??dz]美[?kr?s?ro?dz]dice→dice骰子[dais]gallows→gallows绞刑架['g?l?uz]headquarters→headquarters 总部英[?h?d?kw??t?z]美[?h?d?kw?rt?rz]means→means方法,手段,门路英[mi?nz]美[minz]serie →series系列英[?s??ri?z]美s[?s?riz]species→species物种['spi:? iz]借用单词:英语中有些单词是借用其余语言的。

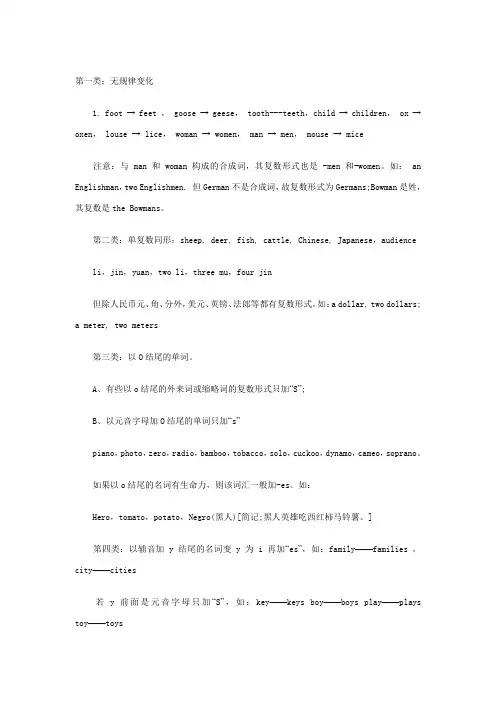

第一类:无规律变化1. foot → feet , goose → geese, tooth---teeth,child → children, ox →oxen, louse → lice, woman → women, man → men, mouse → mice 注意:与 man 和 woman构成的合成词,其复数形式也是 -men 和-women。

如: an Englishman,two Englishmen. 但German不是合成词,故复数形式为Germans;Bowman是姓,其复数是the Bowmans。

第二类:单复数同形:sheep, deer, fish, cattle, Chinese, Japanese,audience li,jin,yuan,two li,three mu,four jin但除人民币元、角、分外,美元、英镑、法郎等都有复数形式。

如:a dollar, two dollars;a meter, two meters第三类:以O结尾的单词。

A、有些以o结尾的外来词或缩略词的复数形式只加“S”;B、以元音字母加O结尾的单词只加“s”piano,photo,zero,radio,bamboo,tobacco,solo,cuckoo,dynamo,cameo,soprano。

如果以o结尾的名词有生命力,则该词汇一般加-es。

如:Hero,tomato,potato,Negro(黑人)[简记;黑人英雄吃西红柿马铃薯。

]第四类:以辅音加y结尾的名词变y为i再加“es”,如:family——families ,city——cities若y前面是元音字母只加“S”,如:key——keys boy——boys play——plays toy——toys第五类:以f,fe结尾的名词,变f,fe为v 加es,如:calf——calves,knife——knivesA.下列名词直接加“S”roof(房顶) reef(暗礁) chief(首领) cliff(悬崖) grief(悲痛) turf(草皮) belief(信仰) gulf(港湾) dwarf(侏儒) safe(保险箱) sheriff(长官) tariff(关税)B. scarf(头巾) whart(码头) staff(全体职员) handkerchief(手帕) hoof(蹄)既可直接加“s”,又可变f为v加es。

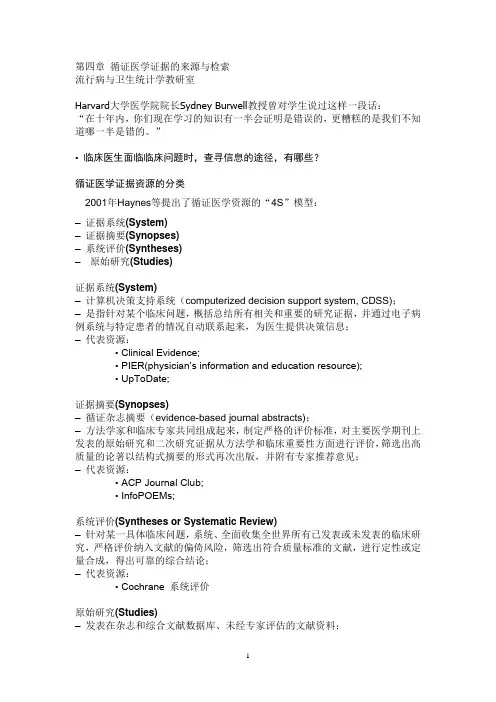

第四章循证医学证据的来源与检索流行病与卫生统计学教研室Harvard大学医学院院长Sydney Burwell教授曾对学生说过这样一段话:“在十年内,你们现在学习的知识有一半会证明是错误的,更糟糕的是我们不知道哪一半是错的。

”• 临床医生面临临床问题时,查寻信息的途径,有哪些?循证医学证据资源的分类2001年Haynes等提出了循证医学资源的“4S”模型:–证据系统(System)–证据摘要(Synopses)–系统评价(Syntheses)–原始研究(Studies)证据系统(System)–计算机决策支持系统(computerized decision support system, CDSS);–是指针对某个临床问题,概括总结所有相关和重要的研究证据,并通过电子病例系统与特定患者的情况自动联系起来,为医生提供决策信息;–代表资源:• Clinical Evidence;• PIER(physician’s information and education resource);• UpToDate;证据摘要(Synopses)–循证杂志摘要(evidence-based journal abstracts);–方法学家和临床专家共同组成起来,制定严格的评价标准,对主要医学期刊上发表的原始研究和二次研究证据从方法学和临床重要性方面进行评价,筛选出高质量的论著以结构式摘要的形式再次出版,并附有专家推荐意见;–代表资源:• ACP Journal Club;• InfoPOEMs;系统评价(Syntheses or Systematic Review)–针对某一具体临床问题,系统、全面收集全世界所有已发表或未发表的临床研究,严格评价纳入文献的偏倚风险,筛选出符合质量标准的文献,进行定性或定量合成,得出可靠的综合结论;–代表资源:• Cochrane 系统评价原始研究(Studies)–发表在杂志和综合文献数据库、未经专家评估的文献资料;–应用时需要严格评估;–容易产生误导;–数量具大,收集困难;–代表资源:• PubMed、Embase• 中国生物医学文献数据库• 知网、万方、维普选择证据资源的标准常用循证医学证据资源系统简介1证据系统– Clinical Evidence• 由BMJ出版,世界最权威性的医学数据库之一• 以治疗为主• 每年更新一次• 采用严格的过程评估每种治疗方法的疗效和安全性• 方便易用,需要付费– PIER• 美国内科医师学会的产品• 内科和初级卫生保健方面的治疗问题• 采用多层次结构指导临床医生应用研究证据• 推荐意见与研究证据紧密相连• 方便易用,需要付费– UpToDate• 电子平台,计算机和PDA可方便获取• 使用方便,覆盖面广,根据疾病分类收集信息• 提供推荐意见,方法严谨,采用GRADE分级• 每4个月更新一次• 缺乏规范检索,付费2证据摘要– ACP Journal Club• 美国内科医师学会出版• ACP Journal Club、EBM杂志、其他以ACP Journal Club为模板的杂志• 先选择高质量原始研究和系统评价,再选择对临床具有重要价值的文献,以结构摘要形式总结,由一名临床专家提出临床应用建议;• 内科及其亚专业• 月刊,付费– InfoPOEM:与ACP Journal Club类似,重点家庭医学–Banbolie:英国国立卫生服务中心提供,主题包括各临床专业、评估的证据3系统评价–Cochrane系统评价• 发表在Cochrane 图书馆• 评价员按统一工作手册,在指导完成• 标准严格,质量高• 主要对防治、康复疗效和安全性的RCT进行评价• CDSR摘要免费,全文需要付费。

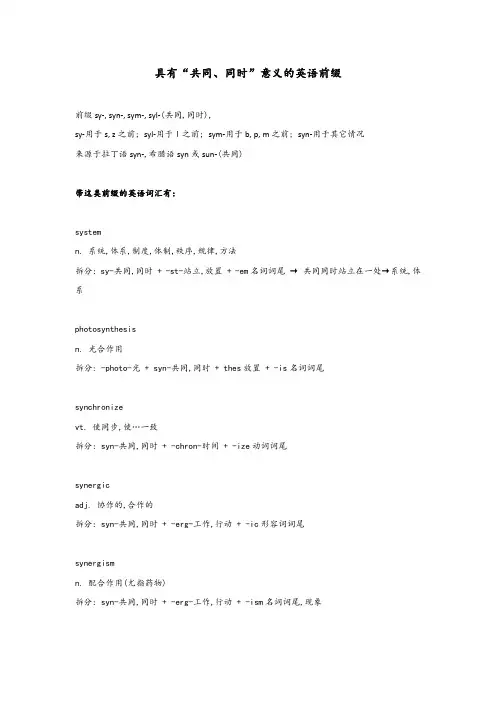

具有“共同、同时”意义的英语前缀前缀sy‐, syn‐, sym‐, syl‐(共同,同时),sy‐用于s, z之前; syl‐用于l之前; sym‐用于b, p, m之前; syn‐用于其它情况来源于拉丁语syn‐,希腊语syn或sun‐(共同)带这类前缀的英语词汇有:systemn. 系统,体系,制度,体制,秩序,规律,方法拆分: sy-共同,同时 + -st-站立,放置 + -em名词词尾 → 共同同时站立在一处→系统,体系photosynthesisn. 光合作用拆分: -photo-光 + syn-共同,同时 + thes放置 + -is名词词尾synchronizevt. 使同步,使…一致拆分: syn-共同,同时 + -chron-时间 + -ize动词词尾synergicadj. 协作的,合作的拆分: syn-共同,同时 + -erg-工作,行动 + -ic形容词词尾synergismn. 配合作用(尤指药物)拆分: syn-共同,同时 + -erg-工作,行动 + -ism名词词尾,现象synonymn. 同义词拆分: syn-共同,同时 + -onym-名→词synopsisn. 情节摘要[简述],提要,提纲;对照表,一览;说明书pl. synopses拆分: syn-共同,同时 + ops(-opt-)视 + -is名词词尾 → 总览synopticaladj. 概略的,以相同观点叙述的拆分: syn-共同,同时 + -opt-视,光 + -ical形容词词尾synthesisn. 综合,合成syntheses拆分: syn-共同,同时 + thesis放置symbiosisn. 共生(现象),共栖拆分: sym-共同,同时 + -bi-生命,生物 + -osis名词词尾symboln. 象征;符号,标志来源于希腊语中由前缀sun-(共同)和ballein(投,掷)组成的复合词sumballein(一起扔→比较→识别→象征/符号)。

不规则的名词复数形式Irregular Noun Plurals A. Vowel change 元音改变man, men 男子woman, women 妇女foot, feet 脚toot, teeth 牙齿goose, geese 鹅mouse, mice 鼠B. 加 -enchild, children 孩子ox, oxen 牛C. f → vthief, thieves 小偷wife, wives 妻子life, lives 生命knife, knives 刀calf, calves 牛犊half, halves 半loaf, loaves 面包shelf, shelves 货架sheaf, sheaves 束wolf, wolves 狼hoof, hooves 蹄D. No singular 没有单数scissors 剪刀,tweezers 镊子,tongs 钳,trousers 裤,slacks 休闲裤, snorts 打着呼噜,pants 短裤,pajamas 睡衣,glasses 眼镜、玻璃杯,spectacles 眼镜,binoculars 望远镜,clothes 衣服,people 人,police 警察,等E. Same 单复数不变sheep 羊,deer 鹿,moose 驼鹿,fish 鱼,trout 鲑鱼,salmon 鳟鱼,bass 低音,series 系列,means species 物种,Chinese 中国人,Japanese 日本人,Swiss 瑞士人,等F. Foreign words 外来词的变化analysis, analyses 分析basis, bases 基础,基地hypothesis, hypotheses 假设parenthesis, parentheses 括号synopsis, synopses 故事梗概,提要thesis, theses 论文crisis, crises 危机stimulus, stimuli 刺激nucleus, nuclei 核alumnus, alumni 校友radius, radii 半径syllabus, syllabi 课程,教学大纲medium, media 媒介,媒体memorandum, memoranda 备忘录curriculum, curricula 课程phenomenon, phenomena 现象criterion, criteria 准则,标准vortex, vortices 涡matrix, matrices 矩阵index, indices 指数。

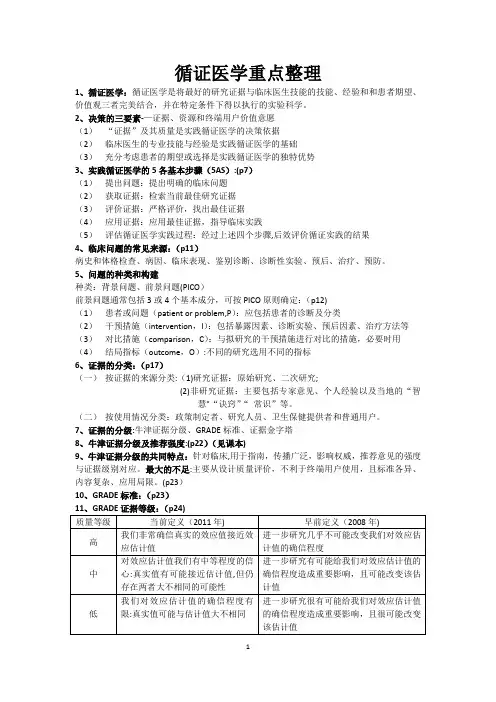

循证医学重点整理1、循证医学:循证医学是将最好的研究证据与临床医生技能的技能、经验和和患者期望、价值观三者完美结合,并在特定条件下得以执行的实验科学。

2、决策的三要素-—证据、资源和终端用户价值意愿(1)“证据”及其质量是实践循证医学的决策依据(2)临床医生的专业技能与经验是实践循证医学的基础(3)充分考虑患者的期望或选择是实践循证医学的独特优势3、实践循证医学的5各基本步骤(5AS):(p7)(1)提出问题:提出明确的临床问题(2)获取证据:检索当前最佳研究证据(3)评价证据:严格评价,找出最佳证据(4)应用证据:应用最佳证据,指导临床实践(5)评估循证医学实践过程:经过上述四个步骤,后效评价循证实践的结果4、临床问题的常见来源:(p11)病史和体格检查、病因、临床表现、鉴别诊断、诊断性实验、预后、治疗、预防。

5、问题的种类和构建种类:背景问题、前景问题(PICO)前景问题通常包括3或4个基本成分,可按PICO原则确定:(p12)(1)患者或问题(patient or problem,P):应包括患者的诊断及分类(2)干预措施(intervention,I):包括暴露因素、诊断实验、预后因素、治疗方法等(3)对比措施(comparison,C):与拟研究的干预措施进行对比的措施,必要时用(4)结局指标(outcome,O):不同的研究选用不同的指标6、证据的分类:(p17)(一)按证据的来源分类:(1)研究证据:原始研究、二次研究;(2)非研究证据:主要包括专家意见、个人经验以及当地的“智慧"“诀窍”“常识”等。

(二)按使用情况分类:政策制定者、研究人员、卫生保健提供者和普通用户。

7、证据的分级:牛津证据分级、GRADE标准、证据金字塔8、牛津证据分级及推荐强度:(p22)(见课本)9、牛津证据分级的共同特点:针对临床,用于指南,传播广泛,影响权威,推荐意见的强度与证据级别对应。

最大的不足:主要从设计质量评价,不利于终端用户使用,且标准各异、内容复杂、应用局限。

英语不规则名词复数表一、分类1.以f 或fe 结尾:大多数以f 或fe 结尾的名词的复数形式时将其转为ves,但个别直接加s:roof →roofs 屋顶[ru:f]gulf →gulfs 海湾[gʌlf]grief →griefs 悲伤, 悲痛, 担心英[ɡriːf ] 美[grif]cliff →cliffs 悬崖, 峭壁[klif]beef →beefs 牛肉英[bi:f] 美[bif]chief →chiefs 首长, 首领[tʃi:f]proof →proofs 证明英[pru:f] 美[pruf]staff →staffs 全体职员英[stɑːf]美[stæf; stɑf]2.元音:有些名称的复数形式是改变它们的元音声:man →men 男[mæn]woman →women 女[ˈwʊmən]fireman →firemen 消防员[ˈfaɪəmən]foot →feet 脚[fʊt]goose →geese 鹅[guːs]tooth →teeth 牙齿英[tu:θ] 美[tuθ]mouse →mice 老鼠[maus]louse →lice 虱子英[laʊs] 美[laʊs; laʊz]3.古代英语:有些是沿用古代英语:child →children 小孩, 儿童[tʃaɪld]ox →oxen 牛, 阉牛英[ɒks] 美[ɑks]4.以o 结尾:有的以o 结尾的单词加“s”:auto →autos [美口] 汽车英[ˈɔːtəʊ] 美[ˈɔtoʊ; ˈɑtoʊ]kangaroo →kangaroos 袋鼠英[ˌkæŋɡəˈruː]美[ˌkæŋgəˈru]kilo →kilos 千克, 公斤['ki:ləu]memo →memos [口] 备忘录英[ˈmɛməʊ; ˈmiːməʊ] 美[ˈmɛmoʊ]photo →photos 照片['fəutəu]piano →pianos 钢琴英[pɪˈænəʊ] 美[piˈɑnoʊ; pjˈænoʊ ]pimento →pimentos 多香果[pi'mentəu] n. 1.蒲桃树的干果制成的香料2.西班牙甘椒pro →pros 赞成意见英[prəʊ] 美[proʊ]con →cons 反对意见英[kɒn] 美[kɑn]solo →solos, soli 独唱, 独奏英[ˈsəʊləʊ] 美[ˈsoʊloʊ]soprano →sopranos 女高音英[səˈprɑːnəʊ] 美[səˈprænoʊ]studio →studios 工作室英[ˈstjuːdɪˌəʊ] 美[ˈstudiˌoʊ; ˈstjudioʊ]tattoo →tattoos 文身英[tæˈtuː]美[tæˈtu]video →videos 视频英[ˈvɪdɪˌəʊ] 美[ˈvɪdiˌoʊ]zoo →zoos 动物园英[zuː]美[zu]bamboo →bamboos 竹子[bæm'bu:]radio →radios 收音机英[ˈreɪdɪəʊ] 美[ˈreɪdiˌoʊ]mulatto →mulattos 白黑混血儿[mju'lætəu]有的则加“es”:echo →echoes 回声, 反响英[ˈɛkəʊ] 美[ˈɛkoʊ]embargo →embargoes 禁运, 禁运令英[ɛmˈbɑːɡəʊ] 美[ɛmˈbɑrgoʊ; ɪmˈbɑrgoʊ]hero →heroes 英雄英['hiərəu] 美['hɪro]potato →potatoes 土豆英[pəˈteɪtəʊ] 美[pəˈteɪtoʊ; pəˈteɪtə]tomato →tomatoes 番茄英[tə'mɑ:təu] 美[tə'meitəu]torpedo →torpedoes 鱼雷, 水雷英[tɔːˈpiːdəʊ] 美[tɔrˈpidoʊ]veto →vetoes 否决, 否决权['vi:təu]negro →negroes 黑人英[ˈniːgrəʊ] 美[ˈnigroʊ]jingo →jingoes 侵略主义,沙文主义['dʒingəu]mango →mangoes 芒果英[ˈmæŋɡəʊ] 美[ˈmæŋgoʊ]有的两种都可以:buffalo →buffalos / buffaloes / buffalo 水牛英[ˈbʌfəˌləʊ] 美[ˈbʌfəˌloʊ]cargo →cargos / cargoes (船/飞机的)货物英[ˈkɑːɡəʊ] 美[ˈkɑrgoʊ]halo →halos / haloes 光环英[ˈheɪləʊ] 美[ˈheɪloʊ]mosquito →mosquitos / mosquitoes 蚊子[məs'ki:təu]motto →mottos / mottoes 箴言, 格言['mɔtəu]no →nos / noes 没有英[nəʊ] 美[noʊ]tornado →tornados / tornadoes 龙卷风英[tɔːˈneɪdəʊ] 美[tɔrˈneɪdoʊ]volcano →volcanos / volcanoes 火山英[vɒlˈkeɪnəʊ] 美[vɑlˈkeɪnoʊ; vɔlˈkeɪnoʊ]zero →zeros / zeroes 零英[ˈzɪərəʊ] 美[ˈzɪroʊ; ˈziroʊ]commando →commands / commandoes 突击员英[kəˈmɑːndəʊ] 美[kəˈmændoʊ; kəˈmɑndoʊ ]5.不变:有的则不变:cod →cod 鳕鱼英[kɒd] 美[kɑd]deer →deer 鹿[diə]fish →fish 鱼, 鱼类[fɪʃ]offspring →offspring 子孙, 后裔, 幼崽英['ɔ:fspriŋ]美['ɔf,sprɪŋ]perch →perch 鲈鱼英[pɜːtʃ] 美[pɜrtʃ]sheep →sheep 绵羊英[ʃiːp]美[ʃip]trout →trou 鲑鱼[traʊt]bison →bison 野牛['baisn]moose →moose 驼鹿英[muːs]美[mus]aircraft →aircraft 飞机, 飞行器英[ˈɛəˌkrɑːft]美[ˈɛrˌkræft]barracks →barracks 兵营[ˈbærəks]crossroads →crossroads 十字路口英[ˈkrɒsˌrəʊdz] 美[ˈkrɔsˌroʊdz]dice →dice 骰子[dais]gallows →gallows 绞刑架['gæləuz]headquarters →headquarters 总部英[ˌhɛdˈkwɔːtəz] 美[ˈhɛdˌkwɔrtərz]means →means 方法, 手段, 途径英[miːnz]美[minz]series →series 系列英[ˈsɪəriːz]美[ˈsɪriz]species →species 物种['spi:ʃiz]6.借用单词:英语中有些单词是借用其他语言的。

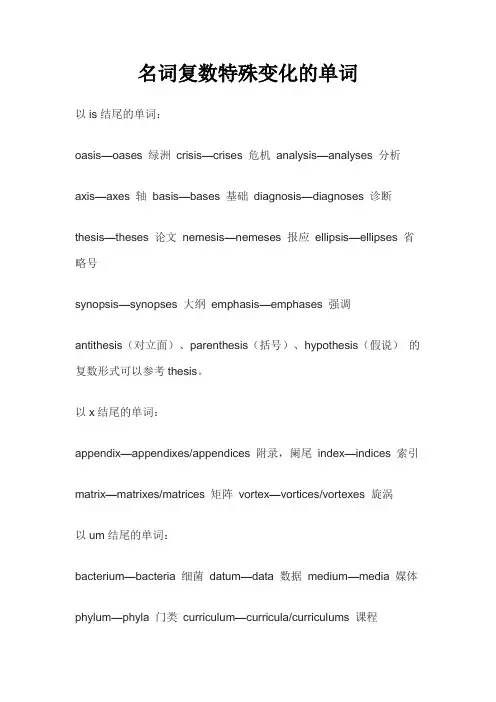

名词复数特殊变化的单词以is结尾的单词:oasis—oases 绿洲crisis—crises 危机analysis—analyses 分析axis—axes 轴basis—bases 基础diagnosis—diagnoses 诊断thesis—theses 论文nemesis—nemeses 报应ellipsis—ellipses 省略号synopsis—synopses 大纲emphasis—emphases 强调antithesis(对立面)、parenthesis(括号)、hypothesis(假说)的复数形式可以参考thesis。

以x结尾的单词:appendix—appendixes/appendices 附录,阑尾index—indices 索引matrix—matrixes/matrices 矩阵vortex—vortices/vortexes 旋涡以um结尾的单词:bacterium—bacteria 细菌datum—data 数据medium—media 媒体phylum—phyla 门类curriculum—curricula/curriculums 课程momentum—momenta 动量quantum—quanta 量子stratum—strata 阶层memorandum—memoranda 备忘录ovum—ova 卵desideratum—desiderata 渴求之物erratum—errata 印刷错误gymnasium—gymnasiums/gymnasia 健身房millennium—millennia 千禧年forum—fora/forums 论坛aquarium—aquaria/aquariums 水族馆symposium—symposia/symposiums 座谈会referendum—referenda/referendums 公民投票dictum—dicta/dictums 名言以us结尾的单词:thesaurus—thesauri/thesauruses 同义词辞典fungus—fungi/funguses 真菌nucleus—nuclei 核uterus—uteri/uteruses 子宫focus—foci/focuses 焦点stimulus—stimuli 刺激syllabus—syllabi/syllabuses 课程表radius—radii/radiuses 半径abacus—abaci/abacuses 算盘terminus—termini/terminuses 终点cactus—cacti/cactuses/cactus 仙人掌genus—genera 属octopus—octopi/octopuses 八爪鱼colossus—colossi 巨像incubus—incubi/incubuses 梦魇corpus—corpora 文集以on结尾的单词:etymon—etymons/etyma 词源phenomenon—phenomena 现象criterion—criteria/criterions 准则lexicon—lexica/lexicons 词汇表automaton—automata/automatons 自动装置以a结尾的单词:larva—larvae 幼虫alga—algae 绿藻aurora—auroras/aurorae 极光antenna—antennae/antennas 触角formula—formulas/formulae 公式nebula—nebulae/nebulas 星云retina—retinae/retinas 视网膜vertebra—vertebrae/vertebras 脊椎vita—vitae个人简历其它:anecdote: anecdotes/anecdota 轶事rhinoceros—rhinoceri/rhinoceros(es) 犀牛trauma—traumata/traumas 创伤bandit—banditti/bandits 强盗dilettante—dilettanti/dilettantes 半吊子virtuoso—virtuosi/virtuosos 技艺精湛者在拉丁语中名词有性、数、格的语法概念,英语在借词过程中甚至也会将这些特征借过来,如:alumnus—alumni 男校友alumna—alumnae 女校友。

一、名词解释1.临床实践指南:是基于当前最好的所有相关证据,并结合当地实际情况、患者需要、现有资源和人们的价值取向所制订的医学实践的原则性的指导性建议。

2.系统评价:全面收集全世界所有有关研究,用统一的标准进行严格评价,筛选合格的文献进行综合,得出当前最可靠的结论。

3.发表偏移:由研究结果自身特性或其结果指向而对研究的发表状态产生影响的一类偏倚。

阳性的研究结果发表的机会更多,发表的速度更快,所发表刊物的影响因子更高。

4.临床医学决策:决策就是做出决定的意思,医学决策是针对医疗卫生实践问题制定解决方案的过程——提出需解决的问题,确定解决问题的目标,制定解决问题的备选方案比较备选方案并做出选择。

5.证据质量分级:明确区分和对待不同来源的证据是循证医学的重要特征之一,主要表现为对证据质量进行分级,并在此基础上做出推荐——GRADE系统将证据质量分为高、中、低、极低四个等级,推荐强度分为强、弱两个等级。

证据质量分级的作用与意义:(1)研究质量的高低与研究结果的真实性与可信性成正比,与结果的不确定性成反比;(2)作为文献检索的指引,文献检索应依证据质量高低,由最好的研究开始,自上而下进行,直到检索到有关证据为止;(3)当不同质量的证据同时具备时,决策必须基于最好来源的证据.二、简答题1.证据演进的5S模式➢证据系统(System):提供决策需要的全部的现有最好的研究证据,以及决策所需要的其他信息的计算机决策支持系统,是证据总结、整理、整合和提供过程的终端,也是证据提供系统的最高形式。

——UpToDate、BMJ Best Practice➢综合证据(Summary):证据总结,关于某疾病各方面的证据。

优点:临床相关性高、易检索、易理解、证据质量好、较简明——Clinical evidence临床证据、临床实践指南➢证据概要(Synopses):对原始研究或系统评价进行严格筛选评价后重新撰写的大纲式摘要,篇幅简短,常用一页可刊载。

•英语不规则名词复数表词的复数形式时将其转为ves,但个别直接加s:*roof → roofs 屋顶* gulf → gulfs 海湾*grief → griefs 悲伤,悲痛, 担心*cliff → cliffs 悬崖, 峭壁* beef → beefs 牛肉*chief → chiefs 首长,首领* proof → proofs 证明* staff → staffs 全体职员2。

元音:改变它们的元音声:* -man → -men 男……* -woman → —women 女……* fireman → firemen 消防员* foot → feet 脚* goose → geese 鹅*tooth → teeth 牙齿* mouse → mice 老鼠*louse → lice 虱子3. 古代英语:有些是沿用古代英语:*child → children 小孩,儿童*ox → oxen 牛,阉牛4. 以o结尾:①以o结尾的单词加“s”:(无生命)*auto → autos [美口] 汽车* kangaroo → kangaroos 袋鼠* kilo → kilos 千克,公斤*memo → memos [口] 备忘录*photo → photos 照片* piano → pianos 钢琴* pimento → pimentos 多香果* pro → pro s 赞成意见*soprano → sopranos 女高音* studio → studios 工作室* tattoo → tattoos 文身* video → videos 视频* zoo → zoos 动物园* bamboo → bamboos 竹子②有的则加“es”(有生命):* echo → echoes 回声,反响*embargo → embargoes 禁运,禁运令* h ero → heroes 英雄*potato → potatoes 土豆*tomato → tomatoes 番茄*torpedo → torpedoes 鱼雷,水雷*veto → vetoes 否决, 否决权* negro → negroes 黑人③有的两种都可以:*buffalo → buffalos / buffaloes / buffalo 水牛*cargo → cargos / cargoes (船/飞机的)货物*halo → halos / haloes 光环*mosquito → mosquitos / mosquitoes 蚊子*motto → mottos / mottoes 箴言,格言*no → nos / noes 没有* tornado → tornados / tornadoes 龙卷风* volcano → volcanos / volcanoes 火山*zero → zeros / zeroes 零*commando → commands / commandoes突击员5. 不变:单复数一样:* cod → co d 鳕鱼*deer → deer 鹿* fish → fish 鱼, 鱼类* offspring → offspring 子孙, 后裔,幼崽*perch → perch 鲈鱼* sheep → sheep 绵羊* trout → trou 鲑鱼* bison → bison 野牛* moose → moose 驼鹿*aircraft → aircraft 飞机, 飞行器*barracks → barracks 兵营*crossroads → crossroads 十字路口*dice → dice 骰子*gallows → gallows 绞刑架*headquarters → headquarters 总部*means → means 方法,手段,途径*series → series 系列*species → species 物种6. 借用单词:英语中有些单词是借用其他语言的。

循证医学证据资源的4S分类一、引言在当今医学领域,循证医学是一个重要的概念。

通过循证医学的方法,医生能够更好地理解和运用医学证据,从而为患者提供更科学、更有效的治疗方案。

而在循证医学中,证据资源的分类是至关重要的一环。

本文将对循证医学证据资源的4S分类进行深度探讨,以便更好地理解循证医学的基本理念和方法。

二、什么是循证医学证据资源的4S分类循证医学证据资源的4S分类是指在循证医学领域中,将医学证据资源分为四大类别:Studies(研究)、Synopses(摘要)、Syntheses (综述)、和Systems(系统)。

这四个类别分别代表了不同深度和广度的医学证据资源,能够帮助医生更全面地了解特定健康问题的证据和治疗方案。

三、Studies(研究)Studies指的是原始医学研究,包括临床试验、队列研究、病例对照研究等。

这些研究提供了医学领域最基础的证据,能够帮助医生了解特定治疗方法的有效性、安全性以及副作用等信息。

通过对这些研究的分析和评估,医生能够得出更科学的诊断和治疗建议,从而为患者提供更优质的医疗服务。

四、Synopses(摘要)Synopses是对大量原始研究的总结和摘要。

这些摘要通常由专业的医学研究机构或学术期刊撰写,将同一领域的多篇原始研究进行概括和概述,从而帮助医生更快速地了解某一健康问题的研究状况。

对于医生来说,阅读Synopses能够节省大量时间,并且更容易获取到领域内最新的研究成果,从而及时更新自己的临床实践。

五、Syntheses(综述)Syntheses指的是将大量相关研究结果进行系统综合和分析,得出综合性结论的工作。

这些综述性的文献往往由专门的医学研究团队或专家撰写,能够为医生提供更系统和更全面的研究结论。

通过阅读Syntheses,医生能够更好地了解某一健康问题的全貌,包括各种研究结果的一致性、差异性以及实际临床意义,从而更准确地制定治疗方案。

六、Systems(系统)Systems指的是将不同健康问题的综合证据进行整合和系统化的工作。

简述循证医学证据资源的4s分类【简述循证医学证据资源的4s分类】1. 什么是循证医学证据资源?循证医学是以循证医学证据为基础,结合临床经验和患者价值观,以最佳的临床决策来指导医疗实践的一种医学方法。

而循证医学证据资源则是指在进行医学研究和实践过程中所产生的各种可供参考的医学证据,它们通常包括了不同类型和层次的证据,帮助医生和研究者做出可靠的医学决策。

2. 什么是4s分类?在循证医学领域,研究者通常将循证医学证据资源进行分类,以便更好地进行评价和应用。

而4s分类即是其中的一种主要分类方法。

它将循证医学证据资源分为:studies、syntheses、synopses、systems。

3. Studies(研究)Studies,即研究,指的是针对特定医学问题所进行的临床研究、实验研究、队列研究、病例对照研究等。

这些研究可以为后续的医学实践提供直接的科学依据,是循证医学证据资源中最直接、最原始的数据来源。

4. Syntheses(综合分析)Syntheses,即综合分析,是指对一系列研究数据进行系统性综合分析,通过meta分析、系统评价等方法将各研究结果进行综合,得出更为全面和客观的结论。

这种资源能够帮助医生更好地把握研究的整体情况和趋势。

5. Synopses(摘要)Synopses,即摘要,是对大量的研究文献进行全面梳理和总结,提炼出重要的、具有代表性的结论和建议,并将其以简洁的形式呈现出来。

这种资源能够帮助医学研究者和临床医生迅速获取到最为精炼和核心的研究成果。

6. Systems(体系)Systems,即体系,是指将循证医学证据资源进行整合、建立成为一个完整的体系,形成可供医学决策参考的指南、规范、数据库等。

这种资源是整个循证医学证据资源中的顶层设计,为医学实践和政策制定提供重要的支持。

7. 个人观点和理解对于循证医学证据资源的4s分类,我认为它很好地切入了循证医学的核心问题:如何从不同层次和角度来获取、评价和应用医学证据。

梗概的意思解释作文英文回答:The term "synopsis" refers to a brief outline or summary of a larger work, such as a book, play, film, or television show. It provides an overview of the main events, characters, and plot points, but does not include detailed descriptions or analysis. Synopses are typically used to introduce the work to potential readers or viewers, to help them decide whether they want to read or watch the full version. They can also be used for research purposes, to quickly gather information about a work without having to read it in its entirety.中文回答:梗概,又称提要或摘要,是指对一部较长的作品(如书籍、戏剧、电影或电视节目)的简短概述或总结。

它提供了主要事件、人物和情节要点的大致情况,但不包括详细的描述或分析。

梗概通常用于向潜在读者或观众介绍该作品,以帮助他们决定是否要阅读或观看完整版本。

它们还可以用于研究目的,以便在不阅读完整作品的情况下快速收集作品相关的信息。

扩展说明:梗概具有以下几种特点:简洁性,梗概通常很短,通常只有几句话或一段话,以避免过于冗长。

客观性,梗概不带有作者的个人观点或解读,而是对作品的忠实描述。

概括性,梗概只包含作品中最关键的信息,省略了次要细节和冗长的描述。

英语词法:可数名词复数构成1、大部分名词的复数,只是通过简单地在词尾追加-s或-es而构成例如:cat—cats,dog—dogs,horse—horses,camera—cameras,bench—benches,coach—coaches,ash—ashes,bush—bushes。

1、1.规范复数后缀-s或-es加在词尾假如单数名词以齿擦音(sibilant )的辅音结尾,后面没有接-e,则在词尾追加-es构成复数;假如单数名词以齿擦音的辅音结尾,后面接-e,则直接在词尾追加-s构成复数;为什么在没有-e结尾时需添加上这个-e再追加-s,一种解释是—为了便于发音需要一个单独的元音,加上-e之后,发音显得自然。

位于以下字母组合之后的添加规则(齿擦音为辅音,发音为[iz]ch [t?例如,bench—benches,coach—coaches,match—matches(例外,loch—lochs,stomach—stomachs,因为这儿的ch[k]发不同的音)s [s]例如:bus—buses,gas—gases,plus—pluses,yes—yeses(注意,单个s不用双写)sh [例如:ash—ashes,bush—bushesss [s]例如:grass—grasses,success—successesx [ks]例如:box—boxes,sphinx—sphinxesz [z]例如:buzz—buzzes,waltz—waltzes (注意,fezzes,quizzes 双写z)发[z]音的专用名词复数构成遵循相同的规则例如:the Joneses(单数Jones[dunz]the Rogerses(单数Rogers [r?dz]the two Charleses(单数Charles [t?ɑ?lz]-es不应当用撇号(替换,例如:the Jones’1、2词尾以辅音字母加y结尾的名词复数(或者说,词尾的y有一个前置元音)变y为i再加-es例如:lady—ladies,soliloquy—soliloquies,spy—spies。

An emerging infection comes to our attention because it involves a newly recognized organism,a known organism that newly started to cause disease, or an organism whose transmission has increased. Although Cryptosporidium is not new,evidence suggests that it is newly spread (in increasingly used day-care centers and possibly in widely distributed water supplies, public pools,and institutions such as hospitals and extended-care facilities for the elderly); it is newly able to cause potentially life-threatening disease in the growing number of immunocompromised patients;and in humans, it is newly recognized, largely since 1982 with the AIDS epidemic. Crypto-sporidium is a most highly infectious enteric pathogen, and because it is resistant to chlorine,small and difficult to filter, and ubiquitous in many animals, it has become a major threat to the U.S. water supply. This article will focus on the recognition and magnitude of cryptosporidiosis,the causative organism and the ease with which it is spread, outbreaks of cryptosporidiosis infection,and its pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment.Recognition and Magnitude of CryptosporidiosisFirst recognized by Clarke and Tyzzer (1) at the turn of the century and well known to veterinarians,Cryptosporidium was reported as a human patho-gen in 1976 by Nime (2). From 1976 until 1982,seven cases of cryptosporidiosis were reported in humans, five of which were in immunosuppressed patients. Since 1982, cryptosporidiosis has been increasingly recognized as a cause of severe, life-threatening diarrhea in patients with AIDS as well as in previously healthy persons (3). Of the first 58 cases of cryptosporidiosis described in humans by 1984, 40 (69%) were in immunocompro-mised patients who contracted severe, often irre-versible, diarrhea (lasting longer than 4 months in 65%); of these 40 patients, 33 (83%) had AI D S (4-6);55% of the 40 immunocompromised patients died.A review of 78 reports of more than 131,000patients and more than 6,000 controls showed Cryptosporidium infection in 2.1% to 6.1% of immuno-competent persons in industrialized and devel-oping countries, respectively, vs. 0.2% to 1.5% in controls (Table 1). A review of an additional 22reports of nearly 2,000 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected persons showed Cryptospori-dium infection in 14% to 24% of HIV-infected persons with diarrhea vs. 0% to 5% of HIV-infected controls without diarrhea (7). SeroepidemiologicCryptosporidiosis: An Emerging,Highly Infectious ThreatRichard L. GuerrantUniversity of Virginia School of MedicineCharlottesville, Virginia, USAAddress for correspondence: Richard L. Guerrant, Division of Geographic and International Medicine, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Health Sciences Center #485,Bldg. MR-4, Rm 3146, Charlottesville, VA 22908; fax: 804-977-5323; e-mail: rlg9a@.Cryptosporidium parvum, a leading cause of persistent diarrhea in developing countries, is a major threat to the U.S. water supply. Able to infect with as few as 30microscopic oocysts, Cryptosporidium is found in untreated surface water, as well as in swimming and wade pools, day-care centers, and hospitals. The organism can cause illnesses lasting longer than 1 to 2 weeks in previously healthy persons or indefinitely in immunocompromised patients; furthermore, in young children in developing countries,cryptosporidiosis predisposes to substantially increased diarrheal illnesses. Recent increased awareness of the threat of cryptosporidiosis should improve detection in patients with diarrhea. New methods such as those using polymerase chain reaction may help with detection of Cryptosporidium in water supplies or in asymptomatic carriers. Although treatment is very limited, new approaches that may reduce secretion or enhance repair of the damaged intestinal mucosa are under study.studies suggest that 17% to 32% of nonimmuno-compromised persons in Virginia, Texas, and Wisconsin, as well as nonimmunocompromised Peace Corps volunteers (before travel), have serologic evidence of Cryptosporidium infection by young adulthood. In contrast, more than half of the children in rural Anhui, China, had serologic evidence of cryptosporidial infection by 5 years of age, and more than 90% of children living in an impoverished area of Fortaleza,Brazil, had serologic evidence of cryptosporidial infection in their first year of life (Figure) (8-11).The OrganismAmong protozoa, C. parvum is the major human pathogen that is also found in numerous mammals. It is slightly smaller than the murine Cryptosporidium , C. muris , and is also distin-guished from the other Cryptosporidium species commonly seen in birds, turkeys, snakes, and fish.Infection begins when a person ingests chlorine-resistant, thick-walled oocysts (7). These hardy oocysts appear to be infectious, with an estimated ID 50 (from studies in humans) of one isolate con-taining only 132 oocysts (12). Infections may occur with ingestion of as few as 30 oocysts; some infections have occurred with just one oocyst (13).When the oocysts reach the upper small bowel, the proteolytic enzymes and bile salts enhance the excystation of four infectious sporo-zoites, which enter the brush border surface epithelium and develop into merozoites capable of replicating either asexually or sexually beneath the cell membrane (but extracytoplasmically) inthe brush border epithelial cell surface. Sexual stages combine to form new oocysts, some of which (perhaps 20% as thin-walled oocysts) may sporu-late and continue infection in the same person,while others (thick-walled oocysts) are excreted.Although few organisms may enter through M cells, systemic infection essentially does not occur;the occasional biliary tract or respiratory tract infections in immunocompromised patients probably reached these sites through the lumenal surface.Cryptosporidiosis OutbreaksNumerous well-documented outbreaks of cryptosporidiosis have occurred. Most of these often waterborne outbreaks have involved subtle problems in the flocculation and/or filtration pro-cess (17-21). These outbreaks culminated in the huge waterborne outbreak in Milwaukee, which was initially thought to be viral gastroenteritis,reported to the State Health Department on April 5, 1993, diagnosed on April 7, and followed by an advisory note that evening to the public to boil all drinking water (Table 2). This became the largest waterborne outbreak in U.S. history and affected an estimated 403,000 persons, thus con-stituting a 52% attack rate among those served by the South Milwaukee water works plant.Several immunocompromised patients died, and many previously healthy persons became ill. The mean duration of illness was 12 days with a range of 1 to 55 days, and the average maximum number of watery diarrheal stools was 19 per day at the peak of illness. While watery diarrhea was the predominant symptom among 93% of confirmedTable 1. Rates of Cryptosporidium infection among immunocompetent and HIV-positive persons in industrialized and developing areas abcPatients Controls with diarrhea without diarrheaImmuno-competent Industr. 2.2%(0.26%-22%)0.2%(0%-2.4%)areas[n=2232/107,329][n=3/1941]Developing 6.1%(1.4%-40.9%) 1.5% (0%-7.5%)areas [n=1486/24,269][n=61/4146]HIV-positiveIndustr.14%(6%-70%)0%(0%-0%)areas[n=148/1074][n=0/35]Developing 24%(8.7%-48%)5%(4.9%-5.3%)areas[n=120/503][n=5/101]aFrom 100 reports of 133,175 patients with diarrhea and 6,223controls. b Ranges given in parentheses. c Data from reference (7).Figure. Prevalence of IgG antibodies to Cryptosporidium parvum, by age, in Brazil, China, and the United States.<6m6-11m1y2-4y5-7y8-10y 11-13y 14-16y 17-29y020406080100120AgeP r e v a l e n c e r a t e (%)cases, other symptoms such as abdominal pain, low-grade fever, and vomiting were not infrequent; 75% of infected nonimmunocompromised persons had an average 10-lb weight loss.Additional outbreaks involving public swim-ming pools and wade pools have further docu-mented the ability of Cryptosporidium to cause infection even when ingested in relatively small amounts of fully chlorinated water (22-26). While the leading causes of 129 drinking and recrea-tional water outbreaks in the United States from 1991 through 1994 were Giardia and Cryptospori-dium, cryptosporidiosis accounted for substantially more cases (even if the Milwaukee outbreak were excluded) (23,24,26). In addition, although Crypto-sporidium oocysts cannot multiply in the environ-ment, an outbreak of foodborne cryptosporidiosis, affecting 54% of those ingesting incriminated freshly pressed apple cider, has been reported (27). In this outbreak, Cryptosporidium oocysts were found in the cider press, as well as in a calf on the farm from which the apples were obtained. There was also a 15% secondary attack rate in house-holds involved in this outbreak. The apparent person-to-person spread in households and institu-tions such as day-care centers and hospitals further documents the highly infectious nature of Cryptosporidium. In an urban slum area in northeastern Brazil, secondary household infections occurred in 58% of households with an infected child (index case) despite the 95% prevalence of antibody in children more than 2 years of age (28).The spread of cryptosporidiosis in day-care centers is well documented, with 14 outbreaks reported in the United States, as well as others in the United Kingdom, France, Portugal, Australia, Chile, and South Africa (29). Illnesses usually occurred in the summer and early fall, especially during August and September in the United States and Portugal. Attack rates were 13% to 90%, with the highest rates found among nontoilet-trained toddlers and staff caring for children in diapers. Overall prevalence rates were usually in the 1.8% to 3.8% range; however, rates as high as 30% in day-care homes were reported (30). During outbreaks, 3.7% to 22.9% of infected children may not have diarrhea; infectious oocysts may be excreted for up to 5 weeks after diarrheal illness ends (31). In addition, numerous nosocomial outbreaks of cryptosporidiosis have occurred among health-care workers as well as patients in bone marrow transplant units, pediatric hospitals, and patient wards with HIV-infected patients (32-37). Further-more, elderly hospitalized patients may also be at risk for Cryptosporidium infection (38). In one Pennsylvania hospital, 45% of nurses, medical stu-dents, and house staff caring for an HIV-positive patient with cryptosporidiosis seroconverted (39).Numerous potential animal and water sources have been found to be infected with Crypto-sporidium. In the Gonçalves Dias slum in Forta-leza, Brazil, 10% of animals (including dogs, pigs, donkeys, and goats), 6.3% during the dry season to 14.3% during the wet season, had Cryptospori-dium in their stool specimens. In addition, 22% of drinking water sources studied were infected with Cryptosporidium oocysts (40). Furthermore, LeChavalier et al. have documented that Crypto-sporidium oocysts were present in 27% of 66 drink-ing water samples obtained from 14 states and one Canadian province (mean of 0.18 NTU) (41,42). Pathogenesis and ImpactC. parvum does not infect tissue beyond the most superficial surface of the intestinal epithe-lium; however, it can derange intestinal function. Although a parasite enterotoxin has been exten-sively sought and some reports have suggested that one may exist (43), this issue remains contro-versial, and the source of substances in the stools of infected animals and patients that induce secretion remains unclear (44). Extensive studies in a piglet model of cryptosporidiosis by Argenzio and colleagues demonstrate the loss of vacuolated villus tip epithelium (approximately two-thirds of the villus surface area), accompanied by an approximate 50% reduction in glucose-coupled sodium cotransport. What remains is a predomi-nance of transitional junctional epithelium, in which increased glutamine metabolism drives a sodium-hydrogen exchange, to which is coupled chloride transport. Thus, glutamine drives neutralTable 2. Symptoms of 205 patients with confirmed cases of cryptosporidiosis during the Milwaukee outbreak a Symptom Percent(%) Watery diarrhea93 mean=12d; med=9d (1-55d)mean=19/d; med=12/d (1-90)39% recurred after 2d freeAbdominal cramps84Weight loss75 (med=10lb, 1-40lb)Fever57 (med=38.3°, 37.2°-40.5°)Vomiting48a Data from reference (21)sodium chloride absorption in an apparent prostaglandin-inhibitable manner in Cryptospori-dium-infected piglet epithelium (45). Furthermore, Argenzio and colleagues have demonstrated increased macrophages that produce increased tumor necrosis factor (TNF) in the lamina propria of Cryptosporidium-infected piglets (46). Although TNF did not directly affect epithelial transport, when a fibroblast monolayer was added, an indo-methacin-inhibitable secretory effect was noted with TNF (46). Consequently, the researchers pro-pose a prostaglandin-dependent secretory effect, which occurs 1) through a bumetanide-inhibitable chloride secretory pathway, predominantly from crypt cells; and 2) through the inhibition of neu-tral sodium chloride absorption through the amiloride-sensitive sodium:hydrogen exchanger, predominantly in the junctional or transitional epithelium during active cryptosporidial infection. Reduced xylose and B-12 absorption are among the effects described in humans and animals with cryptosporidiosis (47-49). Disruption of intestinal barrier function with strikingly increased lactulose to mannitol permeability and absorption has been documented during active symptomatic crypto-sporidial infection in children and in HIV-infected adults (Lima et al., unpublished observations) (50).Cryptosporidium appears to be one of the leading causes of diarrhea, especially persistent diarrhea, among children in northeastern Brazil (51,52). In addition, the incidence of diarrhea has been nearly double for many months in young children after symptomatic cryptosporidial infec-tions, suggesting that the disrupted barrier func-tion in infected children leaves residual damage resulting in increased susceptibility of injured epithelium to additional diarrheal illnesses (Agnew et al., unpub. obs.).Recognition and DiagnosisThe diagnosis of C. parvum in patients with diarrhea is usually made by using acid-fast or immunofluorescence staining on unconcentrated fecal smears. Appropriate concentration methods may enhance detection when small numbers of oocysts are present, but some methods such as formalin-ethyl acetate concentration may result in loss of many oocysts (52,53). While several enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay methods are available for detection of fecal cryptosporidial antigen with 83% to 95% sensitivity in diarrheal specimens, these methods are less sensitive in formed specimens and require more time. Micro-scopy using immunofluorescence antibody is slightly more sensitive and may be faster (54,55).Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) provides a new method that may help detect Cryptospori-dium in water supplies or asymptomatic carriers.A genomic DNA library has been constructed in the plasmid pUC18 for propagation in Escherichia coli.After sequencing a 2.3 kilobase C. parvum-specific fragment, a 400-base sequence with a unique Sty I site has been amplified by using primers of 26 nucleotides each (56). Laxer et al. then used a 20-base probe labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP to detect C. parvum DNA in fixed, paraf-fin-embedded tissue (57). In addition, primers for a 556 BP Cryptosporidium-specific region of the small subunit 18s ribosomal RNA gene have been used to produce a PCR product with unique Mae 1 sites that distinguish C. parvum from C. baileyi and C. muris (58). Available methods for detection of viable oocysts in environmental samples are rela-tively insensitive and under active investigation. Treatment and PreventionDespite numerous attempts at examining transfer factor, hyperimmune colostral antibody, and more than 100 antiparasitic and antimicrobial agents, few agents have shown modest benefit in controlled studies; paromomycin is one of them. Although this agent does not eradicate the para-site in immunocompromised patients, it slightly reduces parasite numbers (from 314 x 106 to 109 x 106 oocysts shed per day) and decreases stool fre-quency, with a tendency toward improved Karnof-sky scores and reduced stool weight (59). In view of its effectiveness in driving sodium cotransport (60) and its success in studies of experimental animals, we are examining a new approach to speeding repair of disrupted intestinal barrier function by using glutamine and its derivatives.The ability of the thick-walled oocysts to persist and spread in the environment and their well-documented resistance to chlorine are respon-sible for the spread of Cryptosporidium even in fully chlorinated water supplies that meet existing turbidity standards in drinking water and swim-ming pools. Although some scientists have noted that 9,600 parts per million (mg/l) of chlorine for one minute of exposure are required to decontami-nate water (14), others have noted that even after exposure to full-strength household bleach (5.25% sodium hypochlorite; 50,000 parts per million) for2 hours, the oocysts still remained infectious for experimental animals (15). While Giardia are 14 to 30 times more susceptible to chlorine dioxide or ozone, respectively, ozone is probably the most effective chemical means of inactivating Crypto-sporidium oocysts (16). Consequently, eradication of the organism from drinking water supplies depends on adequate flocculation and filtration, rather than chlorination. Although previous turbidity requirements were based on the removal of larger parasite cysts such as those of Giardia lamblia or Entamoeba histolytica, the smaller C. parvum oocysts are more difficult to remove. Several waterborne outbreaks, including the recent outbreak in Milwaukee, have occurred with turbidity levels in the 0.45 to 1.7 nephelo-metry turbidity units (NTU) range. In a study of waterborne cryptosporidiosis, predominantly among HI V-positive adults in Clark County, Nevada, Goldstein et al. (1996) report that the outbreak was associated with a substantial number of deaths and that the turbidity of the implicated water never exceeded 0.17 NTU (much lower than the new stan-dard of 0.5 NTU required for 95% of measure-ments each month, with no spikes over 1.0 NTU) (5).New approaches to the eradication of infectious oocysts from water supplies are needed, possibly using reverse osmosis, membrane filtration, or electronic or radiation methods, instead of the ineffective chemical or difficult filtration techniques currently used. Ideally, these new methods would provide low cost, effective treatment that could be applied in developing areas as well. Mean-while, an improved understanding of the patho-genesis and impact of Cryptosporidium infections should aid the development of improved treatment and control of this ubiquitous, highly infectious threat to the water supply and to the people it serves,especially malnourished children and immunocompromised patients around the world. AcknowledgmentsMuch of our work on cryptosporidiosis is supported by an International Collaboration in Infectious Diseases Research Grant #2 U01 AI26512 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. Some of these materials were presented as a part of an American Society for Microbiology symposium on emerging infections at the 95th general meeting in Washington, D.C.Dr. Guerrant is Thomas H. Hunter Professor of International Medicine and director, Office of Interna-tional Health, University of Virginia School of Medicine. He holds several patents on innovative approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of common gastrointestinal illnesses. In addition to his many other contributions, Dr. Guerrant is instrumental in shaping tropical medicine training in the United States. References1.Tyzzer EE. A sporozoan found in the peptic glands ofthe common mouse. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1907;5:12-3.2.Nime FA, Burek JD, Page DL, Holscher MA, YardleyJH.Acute enterocolitis in a human being infected with the protozoan Cryptosporidium. Gastroenterology 1976;70:592-8.3.Current WL. Human cryptosporidiosis. N Engl J Med1983;309:1325-7.4.Navin TR, Juranek DD. Cryptosporidiosis: clinical,epidemiologic, and parasitologic review. Reviews of Infectious Diseases 1984;6:313-27.5.Goldstein ST, Juranek DD, Ravenholt O, HightowerAW, Martin DG, Mesnik JL, et al. Cryptosporidiosis: An outbreak associated with drinking water despite state-of-the-art water treatment. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:4596.Vakil NB, Schwartz SM, Buggy BP, Brummitt CF,Kherellah M, Letzer DM, et al. Biliary cryptosporidiosis in HIV-infected people after the waterborne outbreak of cryptosporidiosis in Milwaukee. N Engl J Med 1996;334:19-23.7.Adal KA, Sterling CR, Guerrant RL. Cryptosporidiumand related species. In: Blaser MJ, Smith PD, Ravdin JI, Greenberg HB, Guerrant RL, editors. Infections of the gastrointestinal tract. New York: Raven Press;1995;72:1107-28.8.Zu S-X, Li J-F, Barrett LJ, Fayer R, Zhu S-Y, McAuliffeJF, et al. Seroepidemiologic study of Cryptosporidium infection in children from rural communities of Anhui, China. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1994;51:1-10.9.Ungar BLP, Soave R, Fayer R, Nash TE. Enzymeimmunoassay detection of immunoglobulin M and G antibodies to Cryptosporidium in immunocompetent and immunocompromised persons. J Infect Dis 1986;153:570-8.10.Ungar BL, Gilman RH, Lanata CF, Peres-Schael I.Seroepidemiology of Cryptosporidium infection in two Latin American populations. J Infect Dis 1988;157:551-6.11.Ungar BL, Mulligan M, Nutman TB. Serologicevidence of Cryptosporidium infection in US volun-teers before and during Peace Corps service in Africa.Arch Intern Med 1989;149:894-7.12.DuPont HL, Chappell CL, Sterling CR, Okhuysen PC,Rose JB, Jakubowski W. The infectivity of Crypto-sporidium parvum in healthy volunteers. N Engl J Med1995;332:855-9.13.Haas CN, Rose JB. Reconciliation of microbial riskmodels and outbreak epidemiology: the case of the Milwaukee outbreak. Proceedings of the American Water Works Association 1994;517-23.14.Centers for Disease Control. Waterborne diseaseoutbreaks, 1986-1988. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ 1990;39:1-13.15.Fayer R. Effect of sodium hypochlorite exposure oninfectivity of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts for neonatal BALB/c mice. Appl Environ Microbiol 1995;61:844-6.16.Korich DG, Mead JR, Madore MS, Sinclair NA, Ster-ling CR. Effects of ozone, chlorine dioxide, chlorine, and monochloramine on Cryptosporidium parvum oocyst viability. Appl Environ Microbiol 1990;56:1423-8. 17.Rush BA, Chapman PA, Ineson RW. Cryptosporidiumand drinking water [Letter]. Lancet 1987;2:632-3. 18.D’Antonio RG, Winn RE, Taylor JP, Gustafson TL,Current WL, Rhodes MM, et al. A waterborne outbreak of cryptosporidiosis in normal hosts. Ann Intern Med 1985;103:886-8.19.Smith HV, Girdwood RWA, Patterson WJ, Hardie R,Green LA, Benton C, et al. Waterborne outbreak of cryptosporidiosis. Lancet 1988;1484.20.Hayes EB, Matte TD, O’Brien TR, McKinley TW,Logsdon GS, Rose JB, et al. Large community outbreak of cryptosporidiosis due to contamination of a filtered public water supply. N Engl J Med 1989;320:1372-6.21.MacKenzie WR, Hoxie NJ, Proctor ME, Gradus MS,Blair KA, Peterson DE, et al. A massive outbreak in Mil-waukee of Cryptosporidium infection transmitted through the public water supply. N Engl J Med 1994;331:161-7.22.McAnulty JM, Fleming DW, Gonzalez AH. A community-wide outbreak of cryptosporidiosis associated with swimming at a wave pool. JAMA 1994;272:1597-600.23.Moore AC, Herwaldt BL, Craun GF, Calderon RL,Highsmith AK, Juranek DD. Surveillance for water-borne disease outbreaks—United States, 1991-1992.MMWR CDC Surveill Summ 1993;42:1-22.24.Kramer MH, Herwaldt BL, Craun GF, Calderon RL,Juranek DD. Surveillance for waterborne-disease outbreaks-United States, 1993-1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1996;45:1-33.25.Gerba CP, Gerba P. Journal of the Swimming Pooland Spa Industry 1996;1:9-18.26.Steiner TS, Thielman NM, Guerrant RL. Protozoalagents: what are the dangers for the public water supply. Annu Rev Med 1996.lard PS, Gensheimer KF, Addiss DG, Sosin DM,Beckett GA, Houck-Jankoski A, et al. An outbreak of cryptosporidiosis from fresh-pressed apple cider [published erratum appears in JAMA 1995 Mar8;273(10):776].JAMA1994;272(20):1592-6.28.Newman RD, Zu S-X, Wuhib T, Lima AAM, GuerrantRL, Sears CL. Household epidemiology of Cryptosporidium parvum infection. Ann Intern Med 1994;120:500-5. 29.Cordell RL, Addiss DG. Cryptosporidiosis in child care set-tings: a review of the literature and recommendations for prevention and control. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1994;13:311-7.30.Diers J, McCallister GL. Occurrence of Crypto-sporidium in home day-care centers in west-central Colorado. J Parasitol 1989;75:637-8.31.Stehr-Green JK, McCaig L, Remson HM, Raines CS,Fox M, Juranek DD. Shedding of oocysts in immuno-competent individuals infected with Cryptosporidium.Am J Trop Med Hyg 1987;36:338-42.32.Baxby D, Hart CA, Taylor C. Human cryptospori-diosis: a possible case of hospital cross infection. BMJ 1983;287:1760-1.33.Dryjanski JD, Gold JWM, Ritchie MT, Kurt RC, LimSL, Armstrong D. Cryptosporidiosis. Case report in a health team worker. Am J Med 1986;80:751-2.34.Collier AC, Miller RA, Meyers JD. Cryptosporidiosisafter marrow transplantation: person-to-person transmission and treatment with spiramycin. Ann Intern Med 1984;101:205-6.35.Gentile G, Venditti M, Micozzi A, Caprioli A, DonelliG, Tirindelli C, et al. Cryptosporidiosis in patients with hematologic malignancies. Reviews of Infectious Diseases1991;13:842-6.36.Navarrete S, Stetler HC, Avila C, Aranda JAG, Santos-Preciado JI. An outbreak of Cryptosporidium diarrhea ina pediatric hospital. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1991;10:248-50.37.Ravn P, Lundgren JD, Kjaeldgaard P, Holten-AndersonW, H jlyng N, Nielsen JO, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of cryptosporidiosis in AIDS patients. BMJ 1991;302:277-80.38.Neill MA, Rice SK, Ahmad NV, Flanigan TP. Crypto-sporidiosis—an unrecognized cause of diarrhea in elderly hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis 1996;22:168-70.39.Koch KL, Phillips DJ, Aber RC, Current WL.Cryptosporidiosis in hospital personnel. Ann Intern Med1985;102:593-6.40.Newman RD, Wuhib T, Lima AA, Guerrant RL, SearsCL. Environmental sources of Cryptosporidium in an urban slum in northeastern Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg1993;49:270-5.41.LeChevallier MW, Norton WD, Lee RG. Occurrence ofGiardia and Cryptosporidium spp. in surface water sup-plies [published erratum appears in Appl Environ Microbiol 1992 Feb;58:780]. Appl Environ Microbiol 1991;57:2610-6.42.LeChevallier MW, Schulz W, Lee RG. Bacterial nutrientsin drinking water. Appl Environ Microbiol 1991;57:857-62.43.Guarino A, Canani RB, Casola A, Pozio E, Russo R, Bruz-zese E, et al. Human intestinal cryptosporidiosis: secre-tory diarrhea and enterotoxic activity in Caco-2 cells. J Infect Dis1995;171:976-83.44.Sears CL, Guerrant RL. Cryptosporiodiosis: the com-plexity of intestinal pathophysiology. Gastroenterology 1994;106:252-4.45.Argenzio RA, Rhoads JM, Armstrong M, Gomez G.Glutamine stimulates prostaglandin-sensitive Na(+)-H+ exchange in experimental porcine cryptosporidiosis [see comments]. Gastroenterology 1994;106:1418-28.46.Argenzio RA, Lecce J, Powell DW. Prostanoids inhibitintestinal NaCl absorption in experimental porcine cryptosporidiosis. Gastroenterology 1993;104:440-7.。