Clinical Deterioration Following Improvement in the NINDS rt-PA Stroke Trial

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:1.43 MB

- 文档页数:9

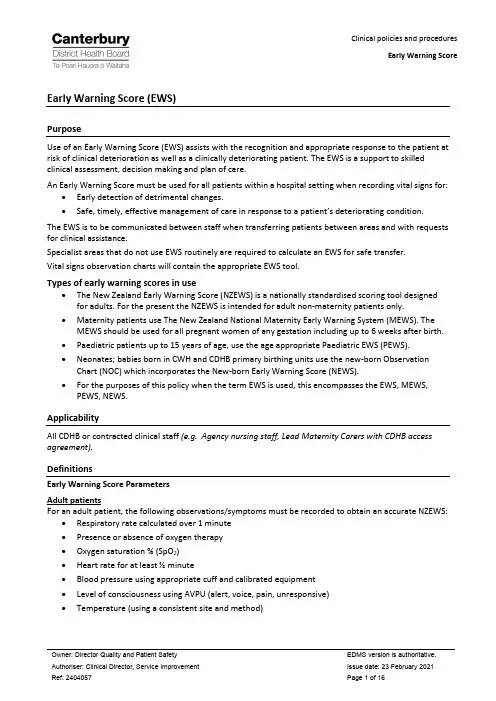

Early Warning Score (EWS)PurposeUse of an Early Warning Score (EWS) assists with the recognition and appropriate response to the patient at risk of clinical deterioration as well as a clinically deteriorating patient. The EWS is a support to skilled clinical assessment, decision making and plan of care.An Early Warning Score must be used for all patients within a hospital setting when recording vital signs for: •Early detection of detrimental changes.•Safe, timely, effective management of care in response to a patient’s deteriorating condition. The EWS is to be communicated between staff when transferring patients between areas and with requests for clinical assistance.Specialist areas that do not use EWS routinely are required to calculate an EWS for safe transfer.Vital signs observation charts will contain the appropriate EWS tool.Types of early warning scores in use•The New Zealand Early Warning Score (NZEWS) is a nationally standardised scoring tool designed for adults. For the present the NZEWS is intended for adult non-maternity patients only.•Maternity patients use The New Zealand National Maternity Early Warning System (MEWS). The MEWS should be used for all pregnant women of any gestation including up to 6 weeks after birth.•Paediatric patients up to 15 years of age, use the age appropriate Paediatric EWS (PEWS).•Neonates; babies born in CWH and CDHB primary birthing units use the new-born Observation Chart (NOC) which incorporates the New-born Early Warning Score (NEWS).•For the purposes of this policy when the term EWS is used, this encompasses the EWS, MEWS, PEWS, NEWS.ApplicabilityAll CDHB or contracted clinical staff (e.g. Agency nursing staff, Lead Maternity Carers with CDHB access agreement).DefinitionsEarly Warning Score ParametersAdult patientsFor an adult patient, the following observations/symptoms must be recorded to obtain an accurate NZEWS: •Respiratory rate calculated over 1 minute•Presence or absence of oxygen therapy•Oxygen saturation % (SpO2)•Heart rate for at least ½ minute•Blood pressure using appropriate cuff and calibrated equipment•Level of consciousness using AVPU (alert, voice, pain, unresponsive)•Temperature (using a consistent site and method)Pregnant women (of any gestation including up to 6 weeks after birth)For a maternity patient, the following observations / symptoms must be recorded to obtain an accurate MEWS:•Respiratory rate calculated over 1 minute•Supplemental oxygen administration(L/min)•Oxygen saturation % (SpO2)•Heart rate for at least ½ minute•Blood pressure•Temperature (using a consistent site and method)•Level of consciousness (normal or abnormal)Paediatric patientsFor a paediatric patient the following observations / symptoms must be completed on admission to obtain accurate PEWS. Subsequent observation requirements are determined by the PEWS management plan, the Nursing Observations and Monitoring Policy [Ref 239155] and/or as indicated by the paediatric medical team.•Respiratory rate calculated over 1 minute•Respiratory distress score•Oxygen saturation % (SpO2)•Heart rate for at least ½ minute•Blood pressure•Level of consciousness using AVPU (alert, voice, pain, unresponsive)•Capillary refill timeNote: Whilst temperature is not included in the PEWS, a baseline temperature recording is taken on admission and four hourly thereafter for an inpatient if within normal limits.NeonatesFor neonates during the immediate post-natal period (1-2 hours) post birth and then at 24 hours, the following should be observed and recorded on the New-born Observation Chart and a NEWS calculated: •Respiratory rate calculated over 1 minute•Work of Breathing•Temperature•Heart rate calculated over a minute•Colour•Behaviour / FeedingAll babies should be assessed against the risks for deterioration as outlined on the New-born Observation Chart and if identified to be at risk then observations and NEWS are performed as instructed and care escalated as required.Education and trainingAll staff within the scope of this procedure must have completed relevant clinical training on the EWS score, escalation and response.Education should be guided by the EWS decision tree.Early Warning Score Procedure Clinical staff responsibilitiesClinical staff responsibilitiesAll patients must have a clinically appropriate plan of care documented, including frequency of monitoring of vital signs, any limitations or ceiling of care and any modification to the response pathway.Staff must be able to perform their responsibilities within this procedure.1.Recognition: Activation1.1.Provide adequate privacy and ensure informed consent1.2.Take the vital signs using appropriate techniques, where applicable inform the patient or caregiverof the results and recording appropriate EWS, check for EWS triggers, and in the absence of Patientrack calculate thescore and record.1.4.Check clinical record for relevant treatment goals and/or plan of care1.5.If escalation pathway triggered, activate according to the response pathway zone colour andfollow plan.1.6.Care for patient, record and act on vital signs as per the EWS zone colour and clinical protocolswhile awaiting review.1.7.Record activation in clinical progress notes or where Cortex is available on the PatientDeterioration Form.1.8.For adults (except maternity), use of the NZEWS activation template is mandatory if a clinicalreview is requested.1.9.For maternity patients, use of the Activation of MEWS Pathway sticker (Ref: 2311278,) or digitalequivalent whenever discussion or further review is requested.Note: The EWS does not replace clinical judgement. Should a clinician or family member be concerned in the absence of a high EWS consider medical review. Within inpatient areas where Kōrero Mai – Patient Family Escalation has been implemented, staff are to support families with escalating care at their request and responding as applicable.2.Response: Escalation2.1.Respond according to the escalation pathway, clinical plans and clinical judgement2.2.Record the response in the clinical notes (using the appropriate response template):a.The EWS triggers and zoneb.Date and time of reviewc.Assessment, decisions and management plan including vital sign frequency (if contrary tothe EWS pathway recommendations) , follow up, higher level of care needs, treatmentlimitations and ceiling of cared.Staff notified and consultede.If a follow up review is required, indicate the timeframe for the review to prevent furtherpatient clinical deterioration.f.If a Senior Medical Officer or Registrar modifies the EWS, the reason is recorded, and themodification must be reviewed by the patient’s Home Team in the am the next day (12noon at the latest).munication / handover/ transfer of care requirementsAny pathway communication / handover or transfer of care with other staff is provided using ‘Identity, Situation, Background, Assessment, Response’ (ISBAR) communication method stating the:a.Patient’s condition / diagnosisb.Patient’s EWSc.The parameters that drove the scored.The actions already been takene.Repeat back the plan of action to take following the communication i.e. repeat EWS in settimeframe and contact medical staff again as required.Measurement / EvaluationUse of early warning system One System Dashboard in clinical governance meetings; regular audit of adherence of the EWS system conducted in areas using the CDHB EWS / MEWS / PEWS / NEWS Audit tool; inclusion in morbidity and mortality meetings.Evaluation can be guided by the EWS decision tree.Associated materialCDHB Resources:•Transfer of patients between hospitals.•ISBAR handover / communication policy.•Deteriorating Patient Activation and Response form document (Ref: 2406526)or digital equivalent Healthlearn•Deteriorating Patient Course (DP001)•New Zealand Early Warning Score•Paediatric Early Warning Score (PE001)•MEWS – Maternity Early Warning Score (RGMY001)•New-born Observation Chart with new-born Early Warning Score (RGMY002)NZEWS Zone / Score (Ref: 2403999) (Appendix 1)NZEWS site specific pathways (Appendix 2)•Christchurch Ref: 2405744•Burwood Ref: 2405791•Hillmorton Ref: 2404730•Ashburton Ref: 2406302PEWS pathway (Appendix 5)Nursing Observation and Monitoring - Paediatrics (Ref: 2405195)EWS decision tree (Appendix 3)MEWS site specific pathways (Appendix 4)•Christchurch Women’s Hospital (Maternity, Birthing Suite, Maternity Assessment Unit, Women’s Outpatient Department) (Ref: 2406285)•Primary Units (Ashburton, Lincoln, Kaikoura, Darfield, Rangiora) (Ref: 2406474)•St. Georges maternity Ref: (2406789)•Activation of MEWS Pathway sticker (Ref: 2404638)•Minimum Frequencies of Observations for Maternity Early Warning Score (MEWS) Chart (Ref: 2404636)NOC/NEWS (Appendix 6)•CDHB New-born Observation Chart 6676 (Ref: 2401230)•CDHB New-born Record QMR0044 (Ref: 2400438)•Observation of mother and baby in the immediate postnatal period: consensus statements guiding practice, MOH, (July 2012)Kōrero Mai - Patient Family Escalation - “Are you Concerned” Signage (Ref: 2407406, 2406997, ,2406998. Shared Goals of Care Document (Ref: 2406924)Appendix One: NZEWS Zone calculatorAppendix two: CDHB NZEWS site specific response pathwaysAppendix three: EWS decision treeAppendix four: Modified Early Obstetric Warning (MEWS) Management Protocol Score and management/responseChristchurch Women’s Hospital(Maternity, Birthing Suite, Maternity Assessment Unit, Women’s Outpatient Department)CDHB Primary Community Maternity Units (Ashburton, Lincoln, Kaikoura, Darfield, Rangiora)St. George’s Maternity UnitAppendix five: Paediatric Early Warning Score (PEWS) Management Protocol Score and management / responseAppendix six: Guide of When to use the New-born Observation Chart and NEWSContentsEarly Warning Score (EWS) (1)Purpose (1)Types of early warning scores in use (1)Applicability (1)Definitions (1)Adult patients (1)Pregnant women (of any gestation including up to 6 weeks after birth) (2)Paediatric patients (2)Neonates (2)Education and training (2)Early Warning Score Procedure Clinical staff responsibilities (3)Clinical staff responsibilities (3)1.Recognition: Activation (3)2.Response: Escalation (3)munication / handover/ transfer of care requirements (4)Measurement / Evaluation (4)Associated material (4)CDHB Resources: (4)Healthlearn (4)Appendix One: NZEWS Zone calculator (5)Appendix two: CDHB NZEWS site specific response pathways (6)Appendix three: EWS decision tree (10)Appendix four: Modified Early Obstetric Warning (MEWS) Management Protocol Score and management/response (11)Christchurch Women’s Hospital (11)CDHB Primary Community Maternity Units (Ashburton, Lincoln, Kaikoura, Darfield, Rangiora) (12)St. George’s Maternity Unit (13)Appendix five: Paediatric Early Warning Score (PEWS) Management Protocol Score and management / response (14)Appendix six: Guide of When to use the New-born Observation Chart and NEWS (15)。

临床研究早期与晚期支架内血栓致4b型急性心肌梗死患者临床结局比较李晓卫1,2,高静1,2,3△,刘寅1,高明东1,肖健勇1摘要:目的 比较早期与晚期支架内血栓(ST)致4b型急性心肌梗死(AMI)患者院内及出院1年生存及预后情况。

方法 入选2015年1月—2018年2月冠状动脉造影确定ST致4b型AMI患者共302例。

根据ST发生时间分为早期ST组(≤30 d)26例和晚期ST组(>30 d)276例,对比2组患者住院期间及出院1年内的终点事件。

主要研究终点包括心源性死亡和再发AMI;次要研究终点包括靶病变血运重建(TLR)、再次ST、心力衰竭及卒中。

采用Kaplan-Meier法绘制生存曲线并比较2组患者无终点事件发生率;采用Cox回归分析4b型AMI患者发生终点事件的危险因素。

结果 住院期间2组主要研究终点事件发生率差异无统计学意义(7.7% vs. 3.3%,P=0.243);早期ST组院内心力衰竭发生率高于晚期ST组(11.5% vs. 1.4%,P=0.016),其他次要终点事件发生率差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

平均随访1年,早期ST组主要(20.0% vs. 5.9%,P<0.05)及次要(36.0% vs. 11.5%,P<0.05)研究终点事件发生率均高于晚期ST组。

Kaplan-Meier生存分析表明,早期ST组1年累积无主要(P=0.022)及次要(P<0.001)终点事件发生率均低于晚期ST组。

Cox回归分析表明高血压、冠状动脉旁路移植术史是4b型AMI患者发生主要终点事件的独立危险因素,术中植入主动脉内气囊泵(IABP)、缩短支架内血栓至球囊扩张(ST to B)时间是其发生次要终点事件的独立保护因素。

结论 与晚期ST致4b型AMI患者相比,早期ST患者院内结局相似,长期预后差。

术中植入IABP、缩短ST to B时间可能改善4b型AMI患者预后。

关键词:心肌梗死;主动脉内气囊泵;支架内血栓;靶病变血运重建中图分类号:R541.4 文献标志码:A DOI:10.11958/20230488Comparison of clinical outcomes in patients with 4b acute myocardial infarction caused by earlyand late stent thrombosisLI Xiaowei1, 2, GAO Jing1, 2, 3△, LIU Yin1, GAO Mingdong1, XIAO Jianyong11 Department of Coronary Care Unit, Chest Hospital, Tianjin University, Tianjin 300222, China;2 Tianjin Medical University;3 Tianjin Cardiovascular Diseases Institute△Corresponding Author E-mail:*******************Abstract: Objective To observe and compare in-hospital and 1-year survival and prognosis of patients with 4b acute myocardial infarction (AMI) caused by early and late stent thrombosis (ST). Methods A total of 302 patients with 4b acute myocardial infarction caused by ST were enrolled in this study from January 2015 to February 2018. ST patients were confirmed by coronary angiography. These patients were divided into two groups: the early ST group (n=26) and the late ST group (n=276) according to the time of ST occurrence. Endpoint events during hospitalization and one year of follow up were compared between the two groups of patients. The primary endpoint events included cardiac death and recurrent AMI. The secondary endpoint events included target lesion revascularization (TLR), re-stent thrombosis, heart failure and stroke. The incidence of no endpoint events was compared between two groups of patients by Kaplan and Meier survival analysis. Cox regression analysis was used to analyze risk factors for endpoint events in patients with type 4b AMI. Results There was no significant difference in the incidence of the primary endpoint events during hospitalization between the two groups (7.7% vs.3.3%,P=0.243). The incidence of heart failure was higher in the early ST group than that of the late ST group (11.5%vs.1.4%, P=0.016). There was no significant difference in the incidence rates of other secondary endpoint events between the two groups (P>0.05). After a mean follow-up of 1 year, the incidence rates of primary endpoint events and the secondary eendpoint events were higher in the early ST group (20.0% vs. 5.9%,P<0.05 and 36.0% vs. 11.5%,P<0.01)than that of the late ST group. Kaplan and Meier survival analysis showed that the 1-year cumulative incidences of non-primary (P= 0.022) and non-secondary events (P<0.001) were lower in the early ST group than those of the late ST group. Cox regression 基金项目:天津市卫健委重点学科项目(TJWJ2022XK032);天津市卫健委科技基金项目(TJWJ2021MS027);天津市科技计划项目(22JCZDJC00130);天津市科委重点项目(20YFZCSY00820);天津市医学重点建设学科项目(TJYXZDXK-055B) 作者单位:1天津大学胸科医院冠心病监护病房(邮编300222);2天津医科大学;3天津市心血管病研究所 作者简介:李晓卫(1982),男,副主任医师,主要从事急性心肌梗死相关研究。

执业医师涉及的英文名称1 Colles骨折:即伸直型骨折。

(桡骨下端骨折)“银叉畸形”“枪刺样”手掌着地2 Smith骨折:即屈曲型骨折(桡骨下端骨折)手背着地3 Barton骨折桡骨远端关节面骨折伴腕关节脱位4 Pauwells角:远端骨折线与两侧髂嵴连线的夹角(Pauwells角)大于50°,为内收骨折。

由于骨折面接触较少,容易再移位,故属于不稳定性骨折。

Pauwells角越大,骨折端所遭受的剪切力越大,骨折越不稳定。

(股骨颈骨折)5 Fehy综合征(Felty综合征,费尔蒂综合征)是指RA(类风湿关节炎)患者伴有脾大、中性粒细胞减少,有的甚至有贫血和血小板减少。

RA患者出现Felty综合征时并非都处于关节炎活动期,其中很多患者合并有下肢溃疡、色素沉着,皮下结节,关节畸形,以及发热、乏力、食欲减退和体重下降等全身表现。

6.Heberden结节:由于骨赘、软骨丧失、关节周围肌肉痉挛以及关节破坏所致。

严重者出现关节畸形,如膝内翻。

手指远侧指间关节侧方增粗,形成Heberden结节。

(骨关节炎)7.Beehterew病:由于颈、腰部不能旋转,侧视时必须转动全身。

若髋关节受累则呈摇摆步态。

个别患者症状始自颈椎,逐渐向下波及胸椎和腰椎,称Beehterew病,(强直性脊柱炎8.Caplan综合征——尘肺患者合并RA时易出现大量肺结节,称之为Caplan综合征,也称类风湿性尘肺病。

9. Down综合征:又称先天愚型或21-三体综合征.10. Guthrie细菌生长抑制试验:筛查苯丙酮尿症.11.麻疹黏膜斑(Koplik斑):为早期诊断麻疹的重要依据。

12.帕氏(Pastia)线;猩红热时,皮肤皱折处如腋窝、肘窝及腹股沟等处,皮疹密集,其间有出血点,形成明显的横纹线。

13. Barrett食管:是指食管下段被覆柱状上皮细胞而言。

这是一种少见病。

主要临床表现是吞咽困难、烧心。

X线检查特征为类似胃溃疡的龛影。

J Neurosurg / Volume 116 / June 2012 J Neurosurg 116:1379–1388, 20121379W. L. Titsworth et al.1380J Neurosurg / Volume 116 / June 2012the ICU and had significant functional limitations 1 year later because of muscle wasting and fatigue. The median 6-minute walk distance in survivors was only 66% of that predicted at 1 year after ICU discharge, with limitations attributed to ICU-acquired morbidities, such as global muscle wasting and weakness, foot drop, joint immobil -ity, and dyspnea. Only 49% of survivors in this study had returned to work at 1 year after discharge. In a systematic review of ICU patients with sepsis, multiorgan failure, or prolonged mechanical ventilation, neuromuscular dys -function was identified in 46% of patients and was as -sociated with prolonged duration of mechanical ventila -tion and length of ICU and hospital stay.31 After 7 days of mechanical ventilation, 25–33% of patients experience clinically visible weakness.11 In a recent study, clinicians found that more than one third of patients with stays in the ICU greater than 2 weeks had at least 2 functionally significant joint contractures.10Low patient mobility is rampant in current ICU prac -tice. A multicenter study of patients with acute lung injury found that only 27% of patients received physical therapy in the ICU, with therapy occurring on only 6% of all ICU days;26 another single-center study found that only 6% of mechanically ventilated patients received physical thera-py in the ICU.25 Krishnagopalan et al.21 demonstrated that during an 8-hour time frame, fewer than 3% of critically ill patients were turned, even though ICU policy man -dated turning patients every 2 hours, and that approxi -mately 50% of patients had no change in body position at all. Finally, Goldhill et al.14 found that the average time between manual turns was 4.85 ± 3.3 hours among 40 different ICUs.With more than 5 million persons experiencing an ICU stay each year, the short- and long-term complica -tions of immobility and bed rest significantly affect pa -tient morbidity, mortality, cost, and quality of life.17 No study has investigated the feasibility or benefit of in -creased mobility on outcome in the neurointensive care unit population. Furthermore, the neurointensive care unit, given its high rate of immobility due to neurological dysfunction, may be an ideal setting for such an interven -tion. In this paper we present the results of a prospective trial of a comprehensive mobility program among neuro -intensive care unit patients at a single center.MethodsShands Hospital at the University of Florida is an 852-bed, tertiary-care medical center with 142 intensive care beds, 30 of which constitute the neurointensive care unit. The neurointensive care unit is overseen by an in -terdisciplinary team composed of vested members from neurosurgery, neurology, critical care medicine, nursing, and social work. Its membership includes neuroscience critical care staff nurses, nurse leaders, social workers, pharmacists, physician extenders, and physicians.Patients and Study DesignThe study population consisted of all consecutive pa -tients admitted to the neurointensive care unit from April 1, 2010, through July 31, 2011 (n = 3291). Patients wereexcluded for age < 18 years, hemodynamic instability, or end of life care. The study consisted of a 10-month pre -intervention surveillance period (April 1, 2010, through January 31, 2011) followed by a 6-month prospective in -tervention phase (February 1–July 31, 2011). Study ap -proval was granted by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida and Shands Hospital.Mobility InterventionThe Comprehensive Mobility Guidelines were devel -oped by the SUF Mobility Task Force, a hospital-wide interdisciplinary team that includes representatives from hospital administration, departmental physicians, rehabil-itation, physical therapy, clinical nurse leaders, and qual-ity management. A literature review was performed and evidence-based best practices were reviewed in detail. Mobility protocols were developed for critical care units and general hospital floors based on evidence review. In addition, a mobility bundle toolkit was developed that included recommendations for equipment purchasing, staff education plans, validation checklists, and practical implementation advice for medical and nursing leaders. The Neuroscience Center inpatient units (neurointensive care unit and two medical/surgical floors) were the pilot units for testing the new mobility protocol. The mobility bundle toolkit was then distributed to each unit’s nursing leadership team for duplication.The keystone of the critical care component of the Comprehensive Mobility Guideline is the PUMP Plus al -gorithm. Progressive mobility is a series of planned move -ments in a sequential manner beginning at a patient’s current mobility status with a goal of returning to his or her baseline level.33 The PUMP Plus algorithm was devel -oped and modified using existing evidence and guidelines including “Progressive Mobility Guidelines for Critically Ill Patients”1 and “Progressive Upright Mobility (PUM) in the ICU: The How-to-Guide”22 at the University of Kansas. The “plus” part of this protocol was the addition of 6 levels for rehabilitation of patients beyond previous protocols (Fig. 1). Steps 6–11 provide clear expectations for patients beyond being “out-of-bed to chair,” which was previously the ultimate mobility “goal” in ICU patients.A neurocritical care subgroup of the SUF Mobility Task Force added these 6 advanced levels to prevent ma -jor deconditioning among able patients without requiring the consultation of the physical therapy team. The stages of PUMP Plus consist of elevating the head of the bed, tilting the bed, sitting in an upright position, sitting on the edge of the bed, standing, sitting in a chair, ambulating in the room, ambulating outside of the room, and exercises as determined by physical therapy/occupational therapy. As patients completed each stage they were automatically encouraged to progress to the next step rather than await a physician’s orders; however, a patient’s maximum activ -ity level could still be determined by physicians. It was believed that this component was critical for the neuroin -tensive care unit population because there are significant numbers of patients who are maintained in the neuro -intensive care unit for detailed monitoring and/or blood pressure and fluid management despite good neurologi -cal function (such as patients with subarachnoid hemor -rhage).J Neurosurg / Volume 116 / June 2012Increased mobility in neurointensive care unit patients1381Importantly, a neurointensive care unit policy, initi -ated by the medical directors and agreed upon by all at -tending physicians in the unit, stated that enrollment in the PUMP Plus program was automatic unless clinically contraindicated and documented by the attending physi -cian. This was an important factor because it communi -cated to the nursing staff that PUMP Plus and mobility were the standard of care and to not mobilize the patient was the exception. This is an important factor in changing the culture of ICU patients who traditionally have been placed on bed rest because of the perception that they are too sick to be out of bed. A physician’s order was required to discontinue PUMP Plus in neurointensive care unit pa -tients. Clinical contraindications for PUMP Plus included unstable spine, active stroke alerts, and/or up to 24 hours after tissue plasminogen activator and endovascular in -tervention, increased intracranial pressure, active resus-citation for life-threatening hemodynamic instability, femoral sheaths, traction, continuous renal replacement therapy, or aggressive modes of ventilation and palliative care. However, ventriculostomies (in the off position) are not a contraindication to PUMP Plus.Additional aspects of the Comprehensive Mobility Guidelines included criteria for use of skilled physical therapy and occupational therapy services, purchasing additional assistive equipment, funding for additional mobility aides, blocked time scheduling for rehabilitation services, and requiring all patients without specific clini -cal contraindications to be out of bed for meals, shower -ing, and toilet use.Data CollectionDemographic information, including morbidity, neu -rointensive care unit LOS, and diagnosis, was obtained from Decision Support Services and chart review. The neurointensive care unit LOS was calculated as a month -ly average for the neurointensive care unit. Hospital LOS was determined for each patient in the 2-week pre- and postintervention observation period by chart review.Mobility was assessed by the I-MOVE tool.23 The I-MOVE tool (Appendix A) records the highest level of mobility obtained by a patient within the previous hour. The stages included sitting upright in bed (1 point), sit -ting on the edge of the bed (10 points), getting out of bed (20 points), walking to the bathroom (30 points), walking outside the room (40 points), or exercising (50 points). All information was recorded by bedside nurses hourly and analyzed during a 2-week collection period immediately preceding the initiative (January 18–31, 2011) and for an -other 2-week period (May 31–June 14, 2011) 4 months after initiation of the mobility initiative.Pressure ulcer data were collected by an Ostomy and Wound Liaison nurse during weekly “Skin Rounds” ev-F ig . 1. The PUMP Plus algorithm. BP = blood pressure; CRRT = continuous renal replacement therapy; cont. = continuous; CXR = chest x-ray (radiograph); HOB = head of bed; HR = heart rate; HTN = hypertension; mgmt = management; O 2Sat = oxygen saturation; PRN = as needed; pt = patient; q2hours = every 2 hours; Q shift = every 8 hour nursing shift; TBerg = Trendelenburg bed position; TID = three times/day; tPA = tissue plasminogen activator.W. L. Titsworth et al.1382J Neurosurg / Volume 116 / June 2012ery Wednesday using the National Pressure Ulcer Advi -sory Panel rating scale.7 All patients were assessed for the presence of pressure ulcers. The pressure ulcers were categorized according to the National Pressure Ulcer Ad -visory Panel scale and ranged from “Stage I” to “Deep Tissue Injury.” The results presented are Stage II and higher “unit acquired” pressure ulcer prevalence.Patient falls and inadvertent tracheal extubations, as well as unplanned central venous catheter and external ventricular drain removals, were used as indicators of protocol safety. These events were recorded as incident reports within a preexisting adverse event monitoring system.Hospital-acquired infection data were regularly col -lected as part of the quality improvement measures and were reported to the Agency for Healthcare and Research Quality. Hospital-acquired infections were defined by the NHSN criteria.Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia. Ventilator-associ-ated pneumonia requires that the patient has an artificial airway (endotracheal tube or tracheostomy) and is me -chanically ventilated for more than 48 hours at the time of culture, or within the 48 hours prior to the onset of the event. Ventilator-associated pneumonia criteria can be met by radiographic, clinical, and/or laboratory criteria as follows.Radiographic criteria require 2 or more serial chest radiographs with at least 1 of the following: new or pro -gressive and persistent infiltrate, consolidation, cavita -tion, or pneumatoceles. Clinical criteria require at least 1 of the following: fever (> 38°C), leukopenia (< 4000 white blood cells/mm 3) or leukocytosis (> 12,000 white blood cells/mm 3), or for adults more than 70 years old, al -tered mental status. In addition, at least 1 of the following is present: new onset of purulent sputum, increased re -spiratory secretions, increased suctioning requirements, new onset or worsening cough, dyspnea, tachypnea, rales, bronchial breath sounds, and worsening gas exchange (O 2 desaturations [PaO 2/FiO 2 < 240], increased O 2 require-ments, or increased ventilator demand). Laboratory crite -ria require at least 1 of the following: positive growth in blood culture not related to another source of infection, positive growth in pleural fluid culture, positive quantita -tive culture from minimally contaminated lower respira -tory tract specimen (bronchoalveolar lavage or protected specimen brushing), and ≥ 5% bronchoalveolar lavage–obtained cells containing intracellular bacteria on direct microscopic examination (Gram stain) or by histopatho -logical examination. Ventilator-associated pneumonia was excluded if the patient was within 48 hours of trans -fer from another facility. The VAP rate per 1000 ventila -tor days was calculated by dividing the number of VAPs by the number of ventilator days and multiplying the re -sult by 1000. The Infection Control Practitioner gathered data on the patient (signs/symptoms, chest radiographs, treatment, and other data) and referred any positive finds to physicians in the Infectious Disease department who reviewed the case and determined whether a VAP met the NHSN definitions.Catheter-Associated UTI. A catheter-associated UTI was an infection that occurred while the patient had a uri -nary catheter in place, or had a catheter in place within 48 hours prior to culture.19 Two possible definitions of UTI were accepted. The first definition included a patient who had at least 1 sign or symptom of UTI and a positive urine culture growing > 105 cfu/ml with no more than 2 mi -croorganisms. Signs and symptoms include temperature > 38°C, urinary urgency, urinary frequency, dysuria, and suprapubic tenderness. The second definition required that a patient have at least 2 signs or symptoms but a less compelling laboratory finding such as a positive dipstick for leukocyte esterase or nitrite, pyuria with ≥ 3 white blood cells/hpf, positive Gram stain, or 2 urine cultures > 102 cfu/ml of a single pathogen in a patient undergo -ing treatment with antimicrobial agents. Asymptomatic catheter-associated bacteriuria or candiduria was defined as a positive urine culture (> 105 cfu/ml) in a patient who had had a urinary catheter within the previous 2 days and who had no signs or symptoms of catheter-associated UTI. Asymptomatic catheter-associated bacteriuria or candiduria were not counted as catheter-associated UTIs in this study. Patients were not routinely monitored for asymptomatic bacteriuria. Urinalysis as well as urine and blood cultures was performed whenever the patients de -veloped systemic or local signs of infection; these includ -ed fever (temperature > 38.5°C), urinary urgency, urinary frequency, dysuria, and suprapubic tenderness.The infection control investigation of possible cathe -ter-associated UTI was triggered by a positive urine cul -ture. An infection control nurse practitioner would then perform a chart review to gather data. These data were presented to the hospital epidemiologist to decide wheth -er an infection based on NHSN definitions had occurred. Catheter-associated UTI rate was defined as the number of patients with catheter-associated UTI divided by the number of indwelling urinary catheter days multiplied by 1000. Catheter utilization was defined by the NHSN definition, which was the total number of catheter days divided by the total number of patient days multiplied by cationThe SUF Mobility Task Force developed and execut -ed a comprehensive education and implementation plan. This plan included policy and guideline development; equipment inventory and purchasing; interdisciplinary education; skills validation checklists for physicians, nurses, and therapists; data collection tools; and shift-to-shift monitoring via a newly designed support tech -nician role. Interdisciplinary educational modules were written and videos were developed to assist learners with practical implementation of the Comprehensive Mobility Guidelines. This education was electronically distributed to all frontline care providers as a mandatory require -ment. In addition, the hospital-wide preoperative surgery and unit admission patient education brochures were re -vised to include the Comprehensive Mobility Guidelines. This education plan was so successful in changing the culture on the neurointensive care unit that the SUF Mo -bility Task Force “bundled” it into a toolkit for unit man -agers throughout the hospital. Elements of the Mobility Checklist are listed in Table 1.J Neurosurg / Volume 116 / June 2012Increased mobility in neurointensive care unit patients1383W. L. Titsworth et al.1384J Neurosurg / Volume 116 / June 2012F ig . 2. Graph showing the change in the average number of record-ed activities per day before and after implementation of the PUMP Plus program. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001; OOB = out of bed.J Neurosurg / Volume 116 / June 2012Increased mobility in neurointensive care unit patients1385Total number of culture-confirmed hospital-acquired infections over time. The dashed line indicates the start of the Mobility Initiative.W. L. Titsworth et al.1386J Neurosurg / Volume 116 / June 2012decrease was observed in the total hospital LOS, from 12 days before the intervention to 8.6 days after the inter -vention, when adjusted for diagnosis, age, and sex. This result is in agreement with those from previous mobil -ity studies. One study,25 in a medical ICU that utilized a similar Mobility Team and protocol model, showed that ICU LOS decreased by 20% and hospital LOS decreased by 23% when adjusted for body mass index and vasopres -sor use. The similarity in these results is encouraging and suggests the reproducibility among differing types of ICU environments.Early mobility of patients is not a new concept. The early ambulation of hospitalized patients was first intro -duced late in World War II in an effort to expedite the recovery of soldiers for return to the battlefield.6 In 1972, the University of Colorado published a photo-illustrated report describing ambulation of a mechanically ventilat -ed patient recovering from respiratory failure.29 Another publication in 19758 from Geisinger Medical Center, in Danville, Pennsylvania, provides similar historical evi -dence of early ambulation for ICU patients.Even minor increases in activity have shown benefi -cial effects in ventilated ICU patients. Twenty prospec -tive randomized controlled trials on rotational therapy in ventilated patients were published between 1987 and 2004, and showed decreases in the incidence of pneu -monia.15 However, studies supporting the early onset of rehabilitation and, more importantly, ambulation in the acute ICU setting are relatively new. The first published report was an uncontrolled study of routine multidisci -plinary, twice-daily rehabilitation therapy in the ICU pro -vided to 103 mechanically ventilated patients. This study demonstrated that activity, including sitting and ambula -tion, was feasible and safe in mechanically ventilated pa -tients.4 Moreover, this study demonstrated benefit, with 69% of these ICU patients ambulating more than 100 feet (30 m) by ICU discharge with a mean distance walked of 212 feet (65 m). Thus far, only 1 study 25 has used a Mobility Team and Mobility Protocol to initiate earlier physical therapy in ICU patients. Morris et al. found that protocol patients were out of bed 6 days earlier (5 vs 11) and had therapy initiated more frequently (91% vs 13%, respectively) and that ICU LOS was 5.5 vs. 6.9 days (p = 0.025). Finally, hospital LOS decreased from 14.5 to 11.2 days (p = 0.006) when adjusted for body mass index and vasopressor usage.The correlation between increased mobility and de -creasing VAP rate was the least surprising finding in this study. Even minor increases in activity have shown ben -eficial effects in ventilated ICU patients. Rotational ther -apy alone, without ambulation, decreases the incidence of pneumonia but has no effect on duration of mechanical ventilation, number of days in intensive care, or hospital mortality.15 Accordingly, the European Society of Inten -sive Care Medicine Task Force on Physiotherapy for Crit -ically Ill Patients recently endorsed evidence-based tar -gets for physiotherapy in the ICU. These targets included deconditioning, impaired airway clearance, atelectasis, intubation avoidance, and weaning failure.16 It is believed that the mucocilliary escalator performs suboptimally when prone and therefore increased upright mobility may allow for increased clearance of secretions.Changes in the catheter-associated UTI rate after in -creased mobility is currently unreported. It is well estab -lished that the duration of catheterization is directly relat -ed to the risk of developing a UTI, with a risk of 3%–10% per day of catheterization. At 1 month, this risk is nearly 100%.9 A retrospective cohort study of 400,000 nursing home patients showed that the ability to walk was associ -ated with a 69% lower rate of hospitalization for UTI and that maintaining or improving mobility reduced the risk of hospitalization for UTI by 38% to 80%.28 One possible explanation is that increased mobility either required the discontinuation of catheters or at least prompted physi -cians to discontinue the use of these catheters more fre -quently. In 1 study by Saint et al.,30 almost 40% of at -tending physicians of patients with unnecessary urinary catheters were unaware that the patient had a urinary catheter in place. This idea is reinforced by the signifi -cantly reduced number of catheter days after initiation of the mobility protocol in this study.It bears mentioning that prior to this mobility project a VAP and UTI initiative had been enacted in our neuro -intensive care unit. However, these interventions predated this initiative by more than 6 months. More importantly, the VAP rate had stabilized prior to beginning the PUMP Plus program. Finally, there were no changes in either the VAP or UTI protocols during this trial in an attempt to control confounding variables.It was our hypothesis that increased mobility would correlate with a decreased incidence of pressure ulcer prevalence, but this was not supported by the data. De -creased mobility has been shown by multiple authors to be an independent risk factor for the creation of pressure ulcers. Keller et al.,20 in a systematic review of the litera -ture, found that decreased mobility was 1 of the 11 likely risk factors for pressure ulcer formation. Allman et al.,3 in a prospective inception cohort study of 286 patients, found that immobility had a relative risk increase of 2.36 for pressure ulcer development. Batson et al.,5 in develop-ment of their pressure ulcer scoring system, found that a patient’s ability to turn was the single highest predictor of ulcer formation. Unfortunately in this study no decrease in pressure ulcer prevalence was observed. This may be secondary to an overall low pressure-ulcer occurrence rate, as both the pre- (2.6%) and postinitiative prevalence rate (4.6%) were far below the NHSN 25th percentile of 7.89%. Therefore, detecting a decrease in pressure ulcer formation may have been made more difficult given the already comparatively low prevalence on this unit.These data suggest that increased mobility is fea -sible and safe for neurointensive care unit patients. A prospective cohort study of early ambulation by Bailey et al.4 showed that in 103 ventilated patients, 1449 activity events were associated with less than 1% of activity-relat -ed adverse events during a 6-month study. However, there are considerable safety concerns that must be addressed prior to initiating such a program, which have been dis -cussed elsewhere.32There is a strong body of literature suggesting that venous thromboembolism should be affected by the in -creasing of mobility. Weill-Engerer et al.34 showed that the rate of deep venous thrombosis was strongly correlat -ed with restriction of mobility. Deep venous thrombosisJ Neurosurg / Volume 116 / June 2012Increased mobility in neurointensive care unit patients1387formation was progressively more likely with decreasing mobility, from limited mobility without immobilization (OR = 1.73) to bedridden during the previous 15 days (OR = 5.64). Unfortunately, these data could not be reliably evaluated in our institution. Our neurointensive care unit does not routinely screen for venous thromboembolism and therefore any observed changes are not based on sys -tematic observation.Significant challenges were encountered during the implementation of this initiative. Namely, acquiring new equipment and support technician positions was not an easy task in such a fiscally difficult time. Acquiring hos -pital administration support for this initiative was impera -tive. Once identified as a patient care priority for improving quality outcomes, the financial resources were ultimately allocated. The Mobility Task Force was concerned that duplication of pilot unit efforts was paramount to achiev -ing consistent success in every unit. For this reason, task force members believed strongly that all unit leadership should be given the Mobility Bundle Toolkit and Mobility Checklist for Managers. Lastly, changing unit and inter -disciplinary culture proved to be the most difficult chal -lenge in this endeavor. Extensive education about current evidence-based guidelines and mandatory enforcement of its completion by interdisciplinary leaders were pivotal in changing the status quo into a culture of early patient mo -bility and complication prevention.Our study has several limitations. First, while mobil -ity data were collected for the entire study period, inten -sive analysis and interpretation were only performed on two 2-week periods (pre- and postinitiative). In our opin -ion, further analysis would have been unduly cumber -some and would have added little to the overall weight of the results. Second, as with any nonrandomized study, the interpretation of results should be conducted with care and causality cannot be determined by the current results. While every attempt was made to control for extraneous factors, the role of unaccounted for variables cannot be determined in a correlational study such as this. These data suggest that further study is necessary and a ran -domized control trial should be instituted to investigate the influence of increased mobility in the ICU setting.ConclusionsCurrent neurointensive care unit practice, with in -creasingly aggressive and continuous monitoring tech -niques, has demonstrated a shift toward sedation and in -activity. The lack of mobility in ICU patients has been well established in previous nonneurological work, as has its detrimental outcomes. Recent literature has be -gun to recognize the physiological benefits of increased mobility in ICU patients, focusing mostly on ventilated medical ICU wards. However, in this paper we present only the second study to investigate the implementation of a comprehensive mobility program (PUMP Plus) and the first reported such initiative in a neurointensive care unit population and the first in a predominantly surgical population. We believe that the significant effect on hos -pital-acquired infections and limitation of restraint merit further randomized control trials as a means to broader implementation.When we first started our unit in 1964, patients whorequired mechanical ventilation were awake and alert and often sitting in a chair . . . these individuals could interact . . . they could feel human. . . .The requirement of high acuity care and available pharmacologic therapy has led to the present situation . . . the awake and alert patient who is anxious or depressed requires a great amount of interaction with the health care team. . . . Understanding of the delicate machine/patient interface seems to be lost these days; thus, the requirement of sedation and paralysis.T homas L. P eTTy , m.D.27AppendixThis article contains an appendix that is available only in the online version of the article.DisclosureDr. Mocco serves as a consultant to Actelion, has received sup -port for nonstudy-related clinical or research effort from ev3, and serves on the advisory boards of Lazarus Effect, Inc., Edge Thera-peutics, NFocus, and Codman Neurovascular.Author contributions to the study and manuscript preparation include the following. Conception and design: Mocco, Titsworth, Hes t er, Correia, Reed, Guin, Layon. Acquisition of data: Titsworth, Hes t er, Correia, Reed, Guin. Analysis and interpretation of data: Moc c o, Titsworth, Hester. Drafting the article: Mocco, Titsworth. Crit i cally revising the article: all authors. Reviewed submitted ver -sion of manuscript: all authors. Approved the final version of the man u script on behalf of all authors: Mocco. Statistical analysis: Tits-worth. Administrative/technical/material support: Titsworth.References1. Ahrens T, Burns S, Phillips J, Vollman K, Whitman J: Progres -sive Mobility Guidelines for Critically Ill Patients. (http:///pdf/suggdlns.pdf) [Accessed February 20, 2012]2. Allen C, Glasziou P, Del Mar C: Bed rest: a potentially harm -ful treatment needing more careful evaluation. Lancet 354: 1229–1233, 19993. Allman RM, Goode PS, Patrick MM, Burst N, Bartolucci AA:Pressure ulcer risk factors among hospitalized patients with activity limitation. JAMA 273:865–870, 19954. Bailey P, Thomsen GE, Spuhler VJ, Blair R, Jewkes J, Bezd -jian L, et al: Early activity is feasible and safe in respiratory failure patients. Crit Care Med 35:139–145, 20075. Batson S, Adam S, Hall G, Quirke S: The development of apressure area scoring system for critically ill patients: a pilot study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 9:146–151, 19936. Bergel RR: Disabling effects of inactivity and importance ofphysical conditioning. A historical perspective. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 16:791–801, 19907. Black JM, Edsberg LE, Baharestani MM, Langemo D, Gold -berg M, McNichol L, et al: Pressure ulcers: avoidable or un -avoidable? Results of the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Consensus Conference. Ostomy Wound Manage 57: 24–37, 20118. Burns JR, Jones FL: Letter: Early ambulation of patients re -quiring ventilatory assistance. Chest 68:608, 1975 (Letter) 9. Chenoweth CE, Saint S: Urinary tract infections, in Jarvis WR(ed): Bennett & Brachman’s Hospital Infections, ed 5. Phil -adelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2007, pp 507–51610. Clavet H, Hébert PC, Fergusson D, Doucette S, Trudel G: Jointcontracture following prolonged stay in the intensive care unit. CMAJ 178:691–697, 200811. De Jonghe B, Bastuji-Garin S, Durand MC, Malissin I, Ro -。

神外杂志英-中文目录(2022年10月) Neurosurgery1.Assessment of Spinal Metastases Surgery Risk Stratification Tools in BreastCancer by Molecular Subtype按照分子亚型评估乳腺癌脊柱转移手术风险分层工具2.Microsurgery versus Microsurgery With Preoperative Embolization for BrainArteriovenous Malformation Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis 显微手术与显微手术联合术前栓塞治疗脑动静脉畸形的系统评价和荟萃分析mentary: Silk Vista Baby for the Treatment of Complex Posterior InferiorCerebellar Artery Aneurysms点评: Silk Vista Baby用于治疗复杂的小脑下后动脉动脉瘤4.Targeted Public Health Training for Neurosurgeons: An Essential Task for thePrioritization of Neurosurgery in the Evolving Global Health Landscape针对神经外科医生的有针对性的公共卫生培训:在不断变化的全球卫生格局中确定神经外科手术优先顺序的一项重要任务5.Chronic Encapsulated Expanding Hematomas After Stereotactic Radiosurgery forIntracranial Arteriovenous Malformations: An International Multicenter Case Series立体定向放射外科治疗颅内动静脉畸形后的慢性包裹性扩张血肿:国际多中心病例系列6.Trends in Reimbursement and Approach Selection for Lumbar Arthrodesis腰椎融合术的费用报销和入路选择趋势7.Diffusion Basis Spectrum Imaging Provides Insights Into Cervical SpondyloticMyelopathy Pathology扩散基础频谱成像提供了脊髓型颈椎病病理学的见解8.Association Between Neighborhood-Level Socioeconomic Disadvantage andPatient-Reported Outcomes in Lumbar Spine Surgery邻域水平的社会经济劣势与腰椎手术患者报告结果之间的关系mentary: Prognostic Models for Traumatic Brain Injury Have GoodDiscrimination But Poor Overall Model Performance for Predicting Mortality and Unfavorable Outcomes评论:创伤性脑损伤的预后模型在预测death率和不良结局方面具有良好的区分性,但总体模型性能较差mentary: Serum Levels of Myo-inositol Predicts Clinical Outcome 1 YearAfter Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage评论:血清肌醇水平预测动脉瘤性蛛网膜下腔出血1年后的临床结局mentary: Laser Interstitial Thermal Therapy for First-Line Treatment ofSurgically Accessible Recurrent Glioblastoma: Outcomes Compared With a Surgical Cohort评论:激光间质热疗用于手术可及复发性胶质母细胞瘤的一线治疗:与手术队列的结果比较12.Functional Reorganization of the Mesial Frontal Premotor Cortex in Patients WithSupplementary Motor Area Seizures辅助性运动区癫痫患者中额内侧运动前皮质的功能重组13.Concurrent Administration of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and StereotacticRadiosurgery Is Well-Tolerated in Patients With Melanoma Brain Metastases: An International Multicenter Study of 203 Patients免疫检查点抑制剂联合立体定向放射外科治疗对黑色素瘤脑转移患者的耐受性良好:一项针对203例患者的国际多中心研究14.Prognosis of Rotational Angiography-Based Stereotactic Radiosurgery for DuralArteriovenous Fistulas: A Retrospective Analysis基于旋转血管造影术的立体定向放射外科治疗硬脑膜动静脉瘘的预后:回顾性分析15.Letter: Development and Internal Validation of the ARISE Prediction Models forRebleeding After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage信件:动脉瘤性蛛网膜下腔出血后再出血的ARISE预测模型的开发和内部验证16.Development of Risk Stratification Predictive Models for Cervical DeformitySurgery颈椎畸形手术风险分层预测模型的建立17.First-Pass Effect Predicts Clinical Outcome and Infarct Growth AfterThrombectomy for Distal Medium Vessel Occlusions首过效应预测远端中血管闭塞血栓切除术后的临床结局和梗死生长mentary: Risk for Hemorrhage the First 2 Years After Gamma Knife Surgeryfor Arteriovenous Malformations: An Update评论:动静脉畸形伽玛刀手术后前2年出血风险:更新19.A Systematic Review of Neuropsychological Outcomes After Treatment ofIntracranial Aneurysms颅内动脉瘤治疗后神经心理结局的系统评价20.Does a Screening Trial for Spinal Cord Stimulation in Patients With Chronic Painof Neuropathic Origin Have Clinical Utility (TRIAL-STIM)? 36-Month Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial神经性慢性疼痛患者脊髓刺激筛选试验是否具有临床实用性(TRIAL-STIM)?一项随机对照试验的36个月结果21.Letter: Transcriptomic Profiling Revealed Lnc-GOLGA6A-1 as a NovelPrognostic Biomarker of Meningioma Recurrence信件:转录组分析显示Lnc-GOLGA6A-1是脑膜瘤复发的一种新的预后生物标志物mentary: The Impact of Frailty on Traumatic Brain Injury Outcomes: AnAnalysis of 691 821 Nationwide Cases评论:虚弱对创伤性脑损伤结局的影响:全国691821例病例分析23.Optimal Cost-Effective Screening Strategy for Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysmsin Female Smokers女性吸烟者中未破裂颅内动脉瘤的最佳成本效益筛查策略24.Letter: Pressure to Publish—A Precarious Precedent Among Medical Students信件:出版压力——医学研究者中一个不稳定的先例25.Letter: Protocol for a Multicenter, Prospective, Observational Pilot Study on theImplementation of Resource-Stratified Algorithms for the Treatment of SevereTraumatic Brain Injury Across Four Treatment Phases: Prehospital, Emergency Department, Neurosurgery, and Intensive Care Unit信件:一项跨四个治疗阶段(院前、急诊科、神经外科和重症监护室)实施资源分层算法的多中心、前瞻性、观察性试点研究的协议26.Risk for Hemorrhage the First 2 Years After Gamma Knife Surgery forArteriovenous Malformations: An Update动静脉畸形伽玛刀手术后前2年出血风险:更新Journal of Neurosurgery27.Association of homotopic areas in the right hemisphere with language deficits inthe short term after tumor resection肿瘤切除术后短期内右半球同话题区与语言缺陷的关系28.Association of preoperative glucose concentration with mortality in patientsundergoing craniotomy for brain tumor脑肿瘤开颅手术患者术前血糖浓度与death率的关系29.Deep brain stimulation for movement disorders after stroke: a systematic review ofthe literature脑深部电刺激治疗脑卒中后运动障碍的系统评价30.Effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors in combination with stereotacticradiosurgery for patients with brain metastases from renal cell carcinoma: inverse probability of treatment weighting using propensity scores免疫检查点抑制剂联合立体定向放射外科治疗肾细胞癌脑转移患者的有效性:使用倾向评分进行治疗加权的反向概率31.Endovascular treatment of brain arteriovenous malformations: clinical outcomesof patients included in the registry of a pragmatic randomized trial脑动静脉畸形的血管内治疗:纳入实用随机试验登记处的患者的临床结果32.Feasibility of bevacizumab-IRDye800CW as a tracer for fluorescence-guidedmeningioma surgery贝伐单抗- IRDye800CW作为荧光导向脑膜瘤手术示踪剂的可行性33.Precuneal gliomas promote behaviorally relevant remodeling of the functionalconnectome前神经胶质瘤促进功能性连接体的行为相关重塑34.Pursuing perfect 2D and 3D photography in neuroanatomy: a new paradigm forstaying up to date with digital technology在神经解剖学中追求完美的2D和三维摄影:跟上数字技术的新范式35.Recurrent insular low-grade gliomas: factors guiding the decision to reoperate复发性岛叶低级别胶质瘤:决定再次手术的指导因素36.Relationship between phenotypic features in Loeys-Dietz syndrome and thepresence of intracranial aneurysmsLoeys-Dietz综合征的表型特征与颅内动脉瘤存在的关系37.Continued underrepresentation of historically excluded groups in the neurosurgerypipeline: an analysis of racial and ethnic trends across stages of medical training from 2012 to 2020神经外科管道中历史上被排除群体的代表性持续不足:2012年至2020年不同医学培训阶段的种族和族裔趋势分析38.Management strategies in clival and craniovertebral junction chordomas: a 29-yearexperience斜坡和颅椎交界脊索瘤的治疗策略:29年经验39.A national stratification of the global macroeconomic burden of central nervoussystem cancer中枢神经系统癌症全球宏观经济负担的国家分层40.Phase II trial of icotinib in adult patients with neurofibromatosis type 2 andprogressive vestibular schwannoma在患有2型神经纤维瘤病和进行性前庭神经鞘瘤的成人患者中进行的盐酸埃克替尼II期试验41.Predicting leptomeningeal disease spread after resection of brain metastases usingmachine learning用机器学习预测脑转移瘤切除术后软脑膜疾病的扩散42.Short- and long-term outcomes of moyamoya patients post-revascularization烟雾病患者血运重建后的短期和长期结局43.Alteration of default mode network: association with executive dysfunction infrontal glioma patients默认模式网络的改变:与额叶胶质瘤患者执行功能障碍的相关性44.Correlation between tumor volume and serum prolactin and its effect on surgicaloutcomes in a cohort of 219 prolactinoma patients219例泌乳素瘤患者的肿瘤体积与血清催乳素的相关性及其对手术结果的影响45.Is intracranial electroencephalography mandatory for MRI-negative neocorticalepilepsy surgery?对于MRI阴性的新皮质癫痫手术,是否必须进行颅内脑电图检查?46.Neurosurgeons as complete stroke doctors: the time is now神经外科医生作为完全中风的医生:时间是现在47.Seizure outcome after resection of insular glioma: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and institutional experience岛叶胶质瘤切除术后癫痫发作结局:一项系统综述、荟萃分析和机构经验48.Surgery for glioblastomas in the elderly: an Association des Neuro-oncologuesd’Expression Française (ANOCEF) trial老年人成胶质细胞瘤的手术治疗:法国神经肿瘤学与表达协会(ANOCEF)试验49.Surgical instruments and catheter damage during ventriculoperitoneal shuntassembly脑室腹腔分流术装配过程中的手术器械和导管损坏50.Cost-effectiveness analysis on small (< 5 mm) unruptured intracranial aneurysmfollow-up strategies较小(< 5 mm)未破裂颅内动脉瘤随访策略的成本-效果分析51.Evaluating syntactic comprehension during awake intraoperative corticalstimulation mapping清醒术中皮质刺激标测时句法理解能力的评估52.Factors associated with radiation toxicity and long-term tumor control more than10 years after Gamma Knife surgery for non–skull base, nonperioptic benignsupratentorial meningiomas非颅底、非周期性良性幕上脑膜瘤伽玛刀术后10年以上与放射毒性和长期肿瘤控制相关的因素53.Multidisciplinary management of patients with non–small cell lung cancer withleptomeningeal metastasis in the tyrosine kinase inhibitor era酪氨酸激酶抑制剂时代有软脑膜转移的非小细胞肺癌患者的多学科管理54.Predicting the growth of middle cerebral artery bifurcation aneurysms usingdifferences in the bifurcation angle and inflow coefficient利用分叉角和流入系数的差异预测大脑中动脉分叉动脉瘤的生长55.Predictors of surgical site infection in glioblastoma patients undergoing craniotomyfor tumor resection胶质母细胞瘤患者行开颅手术切除肿瘤时手术部位感染的预测因素56.Stereotactic radiosurgery for orbital cavernous hemangiomas立体定向放射外科治疗眼眶海绵状血管瘤57.Surgical management of large cerebellopontine angle meningiomas: long-termresults of a less aggressive resection strategy大型桥小脑角脑膜瘤的手术治疗:较小侵袭性切除策略的长期结果Journal of Neurosurgery: Case Lessons58.5-ALA fluorescence–guided resection of a recurrent anaplastic pleomorphicxanthoastrocytoma: illustrative case5-ALA荧光引导下切除复发性间变性多形性黄色星形细胞瘤:说明性病例59.Flossing technique for endovascular repair of a penetrating cerebrovascular injury:illustrative case牙线技术用于血管内修复穿透性脑血管损伤:例证性病例60.Nerve transfers in a patient with asymmetrical neurological deficit followingtraumatic cervical spinal cord injury: simultaneous bilateral restoration of pinch grip and elbow extension. Illustrative case创伤性颈脊髓损伤后不对称神经功能缺损患者的神经转移:同时双侧恢复捏手和肘关节伸展。

2021年9月目录一、引言 (1)二、患者报告结局的定义 (1)三、患者报告结局测量量表的研发、翻译、改进 (2)(一)患者报告结局测量量表的研发 (3)(二)用于患者报告结局测量量表的翻译和/或文化调适 (7)(三)患者报告结局测量量表的改进 (9)四、患者报告结局测量量表的选择与评价 (9)五、临床研究中使用患者报告结局的考虑 (11)(一)估计目标框架 (11)(二)选择患者报告结局作为临床研究终点 (11)(三)研究方案和研究报告中有关量表的阐述 (12)(四)量表的有效应答 (12)(五)缺失数据 (13)(六)多重性问题 (14)(七)结果的解释 (14)(八)PRO/ePRO的质量控制 (15)(九)真实世界研究中PRO/ePRO的使用 (16)六、电子化患者报告结局 (16)(一)ePRO测量 (16)(二)使用ePRO的一般考虑 (17)七、与审评机构的沟通交流 (19)参考文献 (20)附录1:词汇表 (22)附录2:中英文词汇对照 (26)123一、引言4临床结局是评价药物治疗获益与风险的核心依据,如何5准确、可靠、完整地观测临床结局至关重要。

患者报告结局6(patient-reported outcome,PRO)是临床结局的形式之一,在药7物注册临床研究中得到越来越广泛的使用。

另外,随着以患8者为中心的药物研发的理念和实践的不断发展,在药物全生9命周期中获取患者体验数据并将其有效地融入到药物的研10发和评价中日益受到重视,而PRO也是其中的一个重要组11成部分。

12本指导原则旨在阐明PRO的定义以及在药物注册研究13中的适用范围,PRO测量特别是量表研发和使用的一般原则,14PRO数据采集的质量控制,数据分析和解释需要注意的事项,15以及与监管部门的沟通等,为申办者提供药物注册研究中合16理使用PRO数据提供指导性意见。

17本指导原则适用于使用PRO作为终点指标支持药品注18册的临床研究,包括临床试验和真实世界研究。

血管前置所致胎儿失血的诊断标准英文回答:Diagnosis Criteria for Fetal Blood Loss due to Vasa Previa.Vasa previa is a condition where fetal blood vessels cross the internal os of the cervix, making them vulnerable to rupture during labor. The diagnosis of vasa previa is crucial to ensure appropriate management and prevent potential fetal complications.There are several diagnostic criteria used to identify vasa previa:1. Prenatal ultrasound: Ultrasonography is the primary diagnostic tool for vasa previa. It can detect the presence of fetal vessels crossing the cervix and determine their location in relation to the placenta and membranes. Color Doppler imaging can show the blood flow within thesevessels, aiding in the diagnosis.2. Risk factors: Certain risk factors increase the likelihood of vasa previa, such as a low-lying placenta (placenta previa), multiple pregnancies, in vitro fertilization (IVF), and a history of uterine surgery. If any of these risk factors are present, a suspicion of vasa previa should be raised, and further investigations should be conducted.3. Clinical presentation: Vasa previa may present with painless vaginal bleeding, especially when the membranes rupture. However, it is important to note that not all cases of vasa previa present with bleeding. Therefore, relying solely on clinical presentation is not sufficient for diagnosis.4. Confirmatory tests: In cases where vasa previa is suspected based on ultrasound findings or risk factors, confirmatory tests can be performed. These tests include transvaginal color Doppler ultrasound, which can visualize the fetal vessels crossing the cervix, and amniocentesis,which can detect fetal blood in the amniotic fluid.In my personal experience, I encountered a case where a pregnant woman presented with painless vaginal bleeding at 32 weeks of gestation. She had a history of IVF and a low-lying placenta on ultrasound. These findings raised suspicion of vasa previa, and a transvaginal color Doppler ultrasound was performed. The ultrasound revealed fetal vessels crossing the cervix, confirming the diagnosis of vasa previa. The patient was immediately scheduled for a cesarean section to prevent fetal blood loss during labor.中文回答:胎儿失血是由血管前置引起的,血管前置是指胎儿的血管横穿子宫颈的内口,使其在分娩过程中容易破裂。

权威发布|创伤后大出血与凝血病处理的欧洲指南【第五版】背景严重创伤是一个重大的全球公共卫生问题,导致全球每年超过580万人死亡未控制性创伤后出血仍然是创伤患者潜在可预防性死亡的主要原因,并且三分之一的创伤患者在入院时出现凝血功能障碍。

对于这些患者,多器官衰竭且死亡的发生高于没有凝血功能障碍的同类损伤的患者。

与创伤性损伤相关的早期急性凝血病最近被认为是一种多因素疾病。

凝血障碍的严重程度受环境和治疗因素的影响。

此外,凝血病可因创伤相关因素如脑损伤和个体患者相关的因素而变化。

本项欧洲临床实践指南最初发表于2007年,并于2010年“STOP the Bleeding Campaign”的一部分,这是一项在2013年旨在降低创伤性损伤的3年全球发表了大量研究,以深化对创伤凝血病病理生理学的理解,填补关于创伤治疗策略的机制和功效的重要知识空白,并提供基于个体的目标导向治疗以改善严重创伤患者结局的证据。

这些新的信息已整合到当前版本的指南中。

指南推荐1. 初步复苏和预防进一步出血1.1. 缩短延迟时间我们推荐将严重受伤的患者直接转送至合适的创伤中心(1B);推荐尽量减少受伤至出血控制之间的时间(1A)。

1.2. 局部出血管理我们推荐局部压迫法以限制危及生命的出血(1A);对于术前情况下的开放性肢体损伤,我们推荐辅以止血带,以阻止危及生命的出血(1B);对于术前情况下的可疑骨盆骨折,我们推荐辅以骨盆带,以阻止危及生命的出血(1B)。

1.3. 通气我们推荐避免低氧血症(1A);我们推荐对创伤患者进行正常通气(1B);出现脑疝迹象时,我们建议过度通气(2C)。

2. 出血的诊断和监测2.1. 初步评估我们推荐根据患者生理、解剖损伤类型、损伤机制及患者对初始复苏的反映综合评估创伤出血的严重程度(1C);我们建议使用休克指数(SI)来评估低血容量性休克的程度( 2C)2.2. 立即干预对于有明显出血来源、大量失血所致的失血性休克、以及某(些)可疑部位出血的患者,我们推荐应立即进行止血操作(1C)2.3. 进一步评估对于不需要紧急控制出血及未能明确出血来源的患者,我们推荐应立即进一步评估(1C)2.4. 影像学评估对于躯干创伤的患者,我们推荐使用创伤超声焦点评估法(FAST)评估游离液体(1C);我们推荐早期完善全身增强CT(WBCT)评估受伤类型和潜在出血来源(1B)。

医学不良预后英语English: When discussing medical adverse outcomes, it's crucial to consider various factors that can influence prognosis. Patient-related factors such as age, underlying health conditions, and genetic predispositions play a significant role in determining prognosis. Additionally, the nature and severity of the illness or injury, as well as the effectiveness of treatment interventions, heavily impact the eventual outcome. Furthermore, social determinants of health, including socioeconomic status, access to healthcare resources, and social support systems, can profoundly influence prognosis. Psychological factors such as coping mechanisms, resilience, and mental health status also contribute to the overall prognosis. Moreover, healthcare system factors like the quality of care, availability of specialists, and continuity of care can either improve or hinder prognosis. Lastly, environmental factors such as living conditions, exposure to toxins or pollutants, and geographical location can affect the course and outcome of medical conditions. Overall, understanding the multifaceted nature of adverse medical outcomes requires a comprehensive evaluation of patient-related, social, psychological, healthcare system, and environmental factors.中文翻译:在讨论医学不良预后时,考虑到可以影响预后的各种因素至关重要。

- 89 -①泰州市第二人民医院 江苏 泰州 225500基于临床护理路径的快速康复外科干预在初次剖宫产产妇围手术期的应用高小燕①【摘要】 目的:探讨初次剖宫产产妇围手术期采用基于临床护理路径(CNP)的快速康复外科(FTS)干预的效果。

方法:选择2020年1月—2022年3月于泰州市第二人民医院产科行初次剖宫产产妇140例为研究对象。

根据随机数表法分为观察组和对照组,各70例。

对照组采用CNP 干预,观察组采用基于CNP 的FTS 干预;观察两组护理前后的心理指标、生活指标、生化指标及护理效果。

结果:护理前,两组焦虑自评量表(SAS)评分和简明生活质量量表(SF-36)评分比较,差异无统计学意义(P >0.05);护理48 h 后,两组SAS 评分低于护理前,SF-36评分高于护理前,且观察组SAS 评分低于对照组,SF-36评分高于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P <0.05)。

护理前,两组皮质醇(Cor)和超敏C 反应蛋白(hs-CRP)水平比较,差异无统计学意义(P >0.05);护理48 h 后,两组Cor 和hs-CRP 水平均高于护理前,观察组低于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P <0.05)。

观察组术中血流动力学异常率、围手术期母婴并发症发生率均显著低于对照组,住院时间短于对照组,母乳喂养成功率和护理总满意度高于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P <0.05)。

结论:给予初次剖宫产产妇基于CNP 的FTS 干预,能有效提高产妇的自我管理效能,顺利度过围手术期,加速术后康复,提高产科护理质量。

【关键词】 剖宫产 临床护理路径 快速康复外科 围手术期安全 护理质量 doi:10.14033/ki.cfmr.2023.32.023 文献标识码 B 文章编号 1674-6805(2023)32-0089-05 Application of Fast Track Surgery Intervention Based on Clinical Nursing Pathway in Perioperative Period of Puerpera with the First Time Cesarean Section/GAO Xiaoyan. //Chinese and Foreign Medical Research, 2023, 21(32): 89-93 [Abstract] Objective: To explore the effect of fast track surgery (FTS) intervention based on clinical nursing pathway (CNP) in perioperative period for puerpera with the first time cesarean section. Method: A total of 140 puerpera with the first time cesarean section in the Obstetrics Department of Taizhou Second People's Hospital from January 2020 to March 2022 were selected as the study subjects. According to the random number table method, they were divided into observation group and control group, with 70 cases in each group. The control group received CNP intervention, while the observation group received FTS intervention based on CNP. The psychological indicators, life indicators, biochemical indicators and nursing outcomes of both groups before and after nursing were compared. Result: Before nursing, there were no statistically differences in the scores of the self rating anxiety scale (SAS) and the short form quality of life scale (SF-36) between the two groups (P >0.05). After 48 h of nursing, the SAS score of the two groups were lower than those before nursing, and the SF-36 scores were higher than those before nursing, and the SAS score of the observation group was lower than that of the control group, and the SF-36 score was higher than that of the control group, the differences were statistically significant (P <0.05). Before nursing, there were no statistically differences in the levels of cortisol (Cor) and hypersensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) between the two groups (P >0.05). After 48 h of nursing, the levels of Cor and hs-CRP in both groups were higher than those before nursing, the observation group were lower than those in the control group, the differences were statistically significant (P <0.05). The incidence of intraoperative hemodynamic abnormalities, perioperative maternal and infant complications in the observation group were significantly lower than those in the control group, and hospital stay was shorter than the control group, and the success rate of breastfeeding and nursing total satisfaction were higher those in the control group, and the differences were statistically significant (P <0.05). Conclusion: The FTS intervention based on CNP for the first time caesarean section can effectively improve the self-management efficiency of the parturient, successfully pass the perioperative period, accelerate the postoperative recovery, and improve the quality of obstetric nursing. [Key words] Caesarean section Clinical nursing pathway Fast track surgery Perioperative safety Nursing quality First-author's address: Taizhou Second People's Hospital, Taizhou 225500, China 剖宫产是解决孕妇和胎儿异常、改善妊娠结局、降低产科风险、保证母婴安全的手术治疗方法,随着医疗技术水平的提高、人们社会观念改变等因素的影响,越来越多的孕妇选择剖宫产术作为分娩方式,导致剖宫产率一直居高不下[1]。