经济学原理-英文答案ch8

- 格式:doc

- 大小:410.50 KB

- 文档页数:9

经济学原理ch08CHAPTER 81. The market will be in equilibrium with a tax on sales of a good whena.the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied and the price buyers payexceeds the price sellers receive by the per-unit tax.b.the price received by the seller equals the price paid by the buyer and thequantity demanded is less than the quantity supplied by the amount of the tax.c.the tax is equal to the price paid by the buyer and quantity demanded is equalto the quantity supplied.d.there cannot be a market equilibrium with a tax on sales.2. The tax rate on a good is thea.total amount of taxes paid by consumers on that goods.b.total amount of taxes paid by producers on that good.c.total amount of taxes paid by both producers and consumers on that good.d.per-unit tax on a good, expressed as a percentage of its price.3. Deadweight lossa.means that there is a loss to some individuals without a corresponding gain toothers.b.is not really a loss to society because what one individualloses anotherindividual gains.c.can be eliminated by sales taxes.d.can occur even if output is at the efficient level.4. Deadweight loss measuresa.the amount people would pay to gain an additional unit ofa good.b.the loss from economic inefficiency.c.the difference between two efficient situations.d.the amount required to compensate producers for lost surplus due to theimposition of a sales tax.5. The deadweight loss from an economically inefficient situation id equal toa.consumer surplus minus producer surplus.b.consumer surplus plus producer surplus.c.the consumer and producer surplus that people could gain by eliminating thatinefficiency.d.the increase in consumer surplus minus the increase in producer surplus thatpeople could gain by eliminating that inefficiency.6. A per-unit tax on a good creates deadweight loss becausea.it makes demand more inelastic.b.it makes supply more elastic.c.by increasing the price consumers pay, and reducing the price sellers receive,it prevents some mutually beneficial trades.d.the government wastes the tax revenues it receives.7. If the supply curve is perfectly elastic, a per-unit taxa.does not create deadweight loss.b.does not reduce consumer surplus.c.does not reduce producer surplus.d.reduces consumer surplus but increases producer surplus.8. Suppose demand for electricity is perfectly inelastic. A tax on electricity will bea.split between producers and consumers in equal shares.b.paid only by producers.c.paid only by consumers.d.split between producers and consumers in unequal shares.9. The coastal town of Milford, Connecticut recently increased taxes on beachfront property. They did this becausea.taxes on land generate no deadweight loss and lots of revenues forgovernment.b.politicians recognize that the supply of beachfront property is perfectlyinelastic and so the tax would generate no deadweight loss.c.taxes on land are paid entirely by the suppliers since the supply of beachfrontproperty is perfectly inelastic.d.of all of the above.10. When the government increases taxes on labor income,a.people tend to work harder to make up for lost income.b.people tend to work less because their take-home wage is lower.c.most employers reduce employment.d.any of the above, depending on the elasticities of demandand supply.11. Which of the following groups has a relatively elastic supply of labor?a.heads-of-households who must support other people with their income.b.Elderly people on Social Security, who can choose whether or not to work.c.Second earners in a household, who make lower wages than the primary wageearner.d. B and C both have relatively elastic labor supplies.12. Which of the following groups has a relatively inelastic supply of labor?e.heads-of-households who must support other people with their incomes.f.Elderly people on Social Security, who can choose whether or not to work.g.Second earners in a household, who make lower wages than the primary wageearner.h. B and C both have relatively elastic labor supplies.13. Henry George’s arguments were based on the idea thata.income taxes are optimal because they distort incentives.b.income taxes are optimal because they create no deadweight loss.c.taxes on land are optimal because they create no deadweight loss.d.income taxes are optimal because they are paid by employers.14. According to supply-side economists, the U.S. tax systemtends toa.decrease interest rates and loans to businesses.b.dampen incentives to work, save, and invest.c.reduce unemployment and push up the price level.d.provide lower tax rates to people who work on salary.15. According to the Laffer Curve, when taxes are increased from 0 percent to a rate consistent with the maximum point on the curve, tax revenue willa.decrease.b.increase.c.be the same as the tax rate.d.remain constant.16. According to supply-side economists, a policy that ________ will cause productivity to increase, which increase the supply of goods and services in the marketplace.a.increases interest ratesb.decreases inflationc.reduces marginal tax ratesd.funds capital investment in the economy17. In the early 1980s, supply-side economists suggested that the U.S. was ata.the minimum point along its Laffer curve.b.the maximum point along its Laffer curve.c.some point along the rising portion of its Laffer curve.d.some point along the falling portion of its Laffer curve.18. U.S. policymakers disagree most often about the effects of taxation becausea.some are capitalists and some are communists.b.some supply-siders and some are not.c.they have different ideas about relative elasticities of demand and supply.d.some are rich and some are poor.。

Chapter 8The Instruments of Trade PolicyChapter OrganizationBasic Tariff AnalysisSupply, Demand, and Trade in a Single IndustryEffects of a TariffMeasuring the Amount of ProtectionCosts and Benefits of a TariffConsumer and Producer SurplusMeasuring the Costs and BenefitsOther Instruments of Trade PolicyExport Subsidies: TheoryCase Study: Europe’s Common Agricultural PolicyImport Quotas: TheoryCase Study: An Import Quota in Practice: U.S. SugarVoluntary Export RestraintsCase Study: A Voluntary Export Restraint in Practice: Japanese Autos Local Content RequirementsBox: American Buses, Made in HungaryOther Trade Policy InstrumentsThe Effects of Trade Policy: A SummarySummaryAppendix I: Tariff Analysis in General EquilibriumA Tariff in a Small CountryA Tariff in a Large CountryAppendix II: Tariffs and Import Quotas in the Presence of Monopoly The Model with Free TradeThe Model with a TariffThe Model with an Import QuotaComparing a Tariff with a QuotaChapter 8 The Instruments of Trade Policy 33Chapter OverviewThis chapter and the next three focus on international trade policy. Students will have heard various arguments for and against restrictive trade practices in the media. Some of these arguments are sound and some are clearly not grounded in fact. This chapter provides a framework for analyzing the economic effects of trade policies by describing the tools of trade policy and analyzing their effects on consumers and producers in domestic and foreign countries. Case studies discuss actual episodes of restrictive trade practices. An instructor might try to underscore the relevance of these issues by having students scan newspapers and magazines for other timely examples of protectionism at work.The analysis presented here takes a partial equilibrium view, focusing on demand and supply in one market, rather than the general equilibrium approach followed in previous chapters. Import demand and export supply curves are derived from domestic and foreign demand and supply curves. There are a number of trade policy instruments analyzed in this chapter using these tools. Some of the important instruments of trade policy include specific tariffs, defined as taxes levied as a fixed charge for each unit of a good imported; ad valorem tariffs, levied as a fraction of the value of the imported good; export subsidies, which are payments given to a firm or industry that ships a good abroad; import quotas, which are direct restrictions on the quantity of some good that may be imported; voluntary export restraints, which are quotas on trading that are imposed by the exporting country instead of the importing country; and local content requirements, which are regulations that require that some specified fraction of a good is produced domestically.The import supply and export demand analysis demonstrates that the imposition of a tariff drives a wedge between prices in domestic and foreign markets, and increases prices in the country imposing the tariff and lowers the price in the other country by less than the amount of the tariff. This contrasts with most textbook presentations which make the small country assumption that the domestic internal price equals the world price times one plus the tariff rate. The actual protection provided by a tariff willnot equal the tariff rate if imported intermediate goods are used in the production of the protected good. The proper measurement, the effective rate of protection, is described in the text and calculated for a sample problem.The analysis of the costs and benefits of trade restrictions require tools of welfare analysis. The text explains the essential tools of consumer and producer surplus. Consumer surplus on each unit sold is defined as the difference between the actual price and the amount that consumers would have been willing to pay for the product. Geometrically, consumer surplus is equal to the area under the demand curve and above the price of the good. Producer surplus is the difference between the minimum amount for which a producer is willing to sell his product and the price which he actually receives. Geometrically, producer surplus is equal to the area above the supply curve and below the price line. These tools are fundamental to the student’s understanding of the implications of trade polici es and should be developed carefully. The costs of a tariff include distortionary efficiency losses in both consumption and production. A tariff provides gains from terms of trade improvement when and if it lowers the foreign export price. Summing the areas in a diagram of internal demand and supply provides a method for analyzing the net loss or gain from a tariff.Other instruments of trade policy can be analyzed with this method. An export subsidy operates in exactly the reverse fashion of an import tariff. An import quota has similar effects as an import tariff upon prices and quantities, but revenues, in the form of quota rents, accrue to foreign producers of the protected good. Voluntary export restraints are a form of quotas in which import licenses are held by foreign governments. Local content requirements raise the price of imports and domestic goods and do not result in either government revenue or quota rents.34 Krugman/Obstfeld •International Economics: Theory and Policy, Eighth EditionThroughout the chapter the analysis of different trade restrictions are illustrated by drawing upon specific episodes. Europe’s common agricultural policy provides and example of export subsidies in action. The case study corresponding to quotas describes trade restrictions on U.S. sugar imports. Voluntary export restraints are discussed in the context of Japanese auto sales to the United States. The oil import quota in the United States in the 1960’s provides an example of a local content scheme.There are two appendices to this chapter. Appendix I uses a general equilibrium framework to analyze the impact of a tariff, departing from the partial equilibrium approach taken in the chapter. When a small country imposes a tariff, it shifts production away from its exported good and toward the imported good. Consumption shifts toward the domestically produced goods. Both the volume of trade and welfare of the country decline. A large country imposing a tariff can improve its terms of trade by an amount potentially large enough to offset the production and consumption distortions. For a large country, a tariff may be welfare improving.Appendix II discusses tariffs and import quotas in the presence of a domestic monopoly. Free trade eliminates the monopoly power of a domestic producer and the monopolist mimics the actions of a firm in a perfectly competitive market, setting output such that marginal cost equals world price. A tariff raises domestic price. The monopolist, still facing a perfectly elastic demand curve, sets output such that marginal cost equals internal price. A monopolist faces a downward sloping demand curve under a quota.A quota is not equivalent to a tariff in this case. Domestic production is lower and internal price higher when a particular level of imports is obtained through the imposition of a quota rather than a tariff.Answers to Textbook Problems1. The import demand equation, MD, is found by subtracting the home supply equation from the homedemand equation. This results in MD= 80 - 40 ⨯P. Without trade, domestic prices and quantities adjust such that import demand is zero. Thus, the price in the absence of trade is 2.2. a. Foreign’s export supply curve, XS, is XS=-40 + 40⨯P. In the absence of trade, the price is 1.b. When trade occurs, export supply is equal to import demand, XS=MD. Thus, using theequations from Problems 1 and 2a, P= 1.50, and the volume of trade is 20.3. a. The new MD curve is 80 - 40 ⨯ (P+ t) where t is the specific tariff rate, equal to 0.5. (Note: Insolving these problems, you should be careful about whether a specific tariff or ad valorem tariff is imposed. With an ad valorem tariff, the MD equation would be expressed as MD= 80 - 40 ⨯(1 + t)P.) The equation for the export supply curve by the foreign country is unchanged. Solving,we find that the world price is $1.25, and thus the internal price at home is $1.75. The volume of trade has been reduced to 10, and the total demand for wheat at home has fallen to 65 (from thefree trade level of 70). The total demand for wheat in Foreign has gone up from 50 to 55.b. andc. The welfare of the home country is best studied using the combined numerical andgraphical solutions presented below in Figure 8.1.Figure 8.1Chapter 8 The Instruments of Trade Policy 35where the areas in the figure are:a.55(1.75 - 1.50) -0.5(55 - 50)(1.75 - 1.50) = 13.125b. 0.5(55 - 50)(1.75 - 1.50) = 0.625c. (65 - 55)(1.75 - 1.50) = 2.50d. 0.5(70 - 65)(1.75 - 1.50) = 0.625e. (65 - 55)(1.50 - 1.25) = 2.50Consumer surplus change: -(a+ b+ c+ d) =-16.875. Producer surplus change: a= 13.125.Government revenue change: c+ e= 5. Efficiency losses b+ d are exceeded by terms of tradegain e. (Note: In the calculations for the a, b, and d areas, a figure of 0.5 shows up. This isbecause we are measuring the area of a triangle, which is one-half of the area of the rectangledefined by the product of the horizontal and vertical sides.)4. Using the same solution methodology as in Problem 3, when the home country is very small relativeto the foreign country, its effects on the terms of trade are expected to be much less. The smallcountry is much more likely to be hurt by its imposition of a tariff. Indeed, this intuition is shown in this problem. The free trade equilibrium is now at the price $1.09 and the trade volume is now$36.40.With the imposition of a tariff of 0.5 by Home, the new world price is $1.045, the internal home price is $1.545, home demand is 69.10 units, home supply is 50.90, and the volume of trade is 18.20.When Home is relatively small, the effect of a tariff on world price is smaller than when Home is relatively large. When Foreign and Home were closer in size, a tariff of 0.5 by home lowered world price by 25 percent, whereas in this case the same tariff lowers world price by about 5 percent. The internal Home price is now closer to the free trade price plus t than when Home was relatively large.In this case, the government revenues from the tariff equal 9.10, the consumer surplus loss is 33.51, and the producer surplus gain is 21.089. The distortionary losses associated with the tariff (areas b+ d) sum to 4.14 and the terms of trade gain (e) is 0.819. Clearly, in this small country example, the distortionary losses from the tariff swamp the terms of trade gains. The general lesson is the smaller the economy, the larger the losses from a tariff since the terms of trade gains are smaller.5. ERP = (200 ⨯ 1.50 - 200)/100 = 100%6. The effective rate of protection takes into consideration the costs of imported intermediate goods.Here, 55% of the cost can be imported, suggesting with no distortion, home value added would be 45%. A 15% increase in the price of ethanol, though, means home value added could be as high as 60%. Effective rate of protection = (V t-V w)/V w, where V t is the value added in the presence of trade policies, and V w is the value added without trade distortions. In this case, we have (60 - 45)/45 = 33% effective rate of protection.7. We first use the foreign export supply and domestic import demand curves to determine the newworld price. The foreign supply of exports curve, with a foreign subsidy of 50 percent per unit,becomes XS=-40 + 40(1 + 0.5) ⨯P. The equilibrium world price is 1.2 and the internal foreign price is 1.8. The volume of trade is 32. The foreign demand and supply curves are used to determine the costs and benefits of the subsidy. Construct a diagram similar to that in the text and calculate the area of the various polygons. The government must provide (1.8 - 1.2)⨯ 32 = 19.2 units of output to support the subsidy. Foreign producers surplus rises due to the subsidy by the amount of 15.3 units of output. Foreign consumers surplus falls due to the higher price by 7.5 units of the good. Thus, the net loss to Foreign due to the subsidy is 7.5 + 19.2 - 15.3 = 11.4 units of output. Home consumers and producers face an internal price of 1.2 as a result of the subsidy. Home consumers surplus rises by 70 ⨯ 0.3 + 0.5 (6⨯ 0.3) = 21.9, while Home producers surplus falls by 44 ⨯ 0.3 + 0.5(6 ⨯ 0.3) =14.1, for a net gain of 7.8 units of output.36 Krugman/Obstfeld •International Economics: Theory and Policy, Eighth Edition8. a. False, unemployment has more to do with labor market issues and the business cycle than withtariff policy.b. False, the opposite is true because tariffs by large countries can actually reduce world priceswhich helps offset their effects on consumers.c. This kind of policy might reduce automobile production and Mexico, but also would increase theprice of automobiles in the United States, and would result in the same welfare loss associatedwith any quota.9. At a price of $10 per bag of peanuts, Acirema imports 200 bags of peanuts. A quota limiting theimport of peanuts to 50 bags has the following effects:a. The price of peanuts rises to $20 per bag.b. The quota rents are ($20 - $10) ⨯ 50 = $500.c. The consumption distortion loss is 0.5 ⨯ 100 bags ⨯ $10 per bag = $500.d. The production distortion loss is 0.5 ⨯ 50 bags ⨯ $10 per bag = $250.10. The reason is largely that the benefits of these policies accrue to a small group of people and thecosts are spread out over many people. Thus, those that benefit care far more deeply about these policies. These typical political economy problems associated with trade policy are probably even more troublesome in agriculture, where there are long standing cultural reasons for farmers andfarming communities to want to hold onto their way of life, making the interests even moreentrenched than they would normally be.11. It would improve the income distribution within the economy since wages in manufacturing wouldincrease, and real incomes for others in the economy would decrease due to higher prices formanufactured goods. This is true only under the assumption that manufacturing wages are lower than all others in the economy. If they were higher than others in the economy, the tariff policies would worsen the income distribution.。

曼昆-十大经济学原理,中英文对照第一篇:曼昆-十大经济学原理,中英文对照十大经济学原理。

曼昆在《经济学原理》一书中提出了十大经济学原理,他们分别是:十大经济学原理一:人们面临权衡取舍。

人们为了获得一件东西,必须放弃另一件东西。

决策需要对目标进行比较。

People Face Trade offs.To get one thing, you have to give up something else.Making decisions requires trading off one goal against another.例子:这样的例子很多,典型的是在“大炮与黄油”之间的选择,军事上所占的资源越多,可供民用消费和投资的资源就会越少。

同样,政府用于生产公共品的资源越多,剩下的用于生产私人品的资源就越少;我们用来消费的食品越多,则用来消费的衣服就越少;学生用于学习的时间越多,那么用于休息的时间就越少。

十大经济学原理二:某种东西的成本是为了得到它所放弃的东西。

决策者必须要考虑其行为的显性成本和隐性成本。

The Cost of Something is what You Give Up to Get It.Decision-makers have to consider both the obvious and implicit costs of their actions.例子:某公司决定在一个公园附近开采金矿的成本。

开采者称由于公园的门票收入几乎不受影响,因此金矿开采的成本很低。

但可以发现伴随着金矿开采带来的噪声、水和空气的污染、环境的恶化等,是否真的不会影响公园的风景价值?尽管货币价值成本可能会很小,但是考虑到环境和自然生态价值会丧失,因此机会成本事实上可能很大。

十大经济学原理三:理性人考虑边际量。

理性的决策者当且仅当行动的边际收益超过边际成本时才采取行动。

Rational People Think at Margin.A rational decision-makertakes action if and only if the marginal benefit of the action exceeds the marginal cost.例子:“边际量”是指某个经济变量在一定的影响因素下发生的变动量。

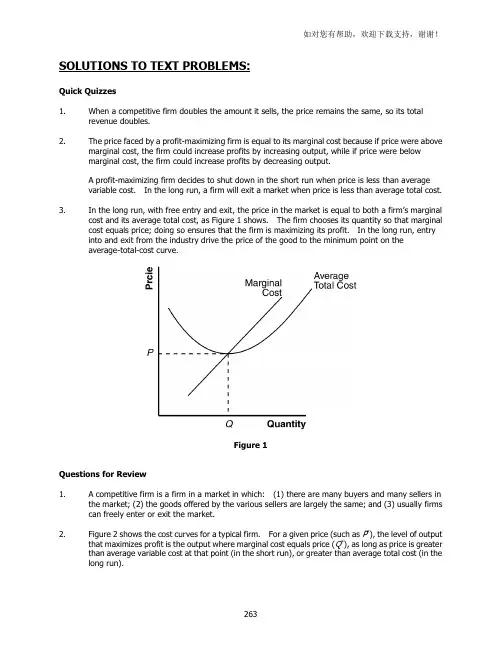

SOLUTIONS TO TEXT PROBLEMS:Quick Quizzes1. When a competitive firm doubles the amount it sells, the price remains the same, so its totalrevenue doubles.2. The price faced by a profit-maximizing firm is equal to its marginal cost because if price were abovemarginal cost, the firm could increase profits by increasing output, while if price were belowmarginal cost, the firm could increase profits by decreasing output.A profit-maximizing firm decides to shut down in the short run when price is less than averagevariable cost. In the long run, a firm will exit a market when price is less than average total cost.3. In the long run, with free entry and exit, the price in the market is equal to both a firm’s marginalcost and its average total cost, as Figure 1 shows. The firm chooses its quantity so that marginal cost equals price; doing so ensures that the firm is maximizing its profit. In the long run, entry into and exit from the industry drive the price of the good to the minimum point on theaverage-total-cost curve.Figure 1Questions for Review1. A competitive firm is a firm in a market in which: (1) there are many buyers and many sellers inthe market; (2) the goods offered by the various sellers are largely the same; and (3) usually firms can freely enter or exit the market.2. Figure 2 shows the cost curves for a typical firm. For a given price (such as P*), the level of outputthat maximizes profit is the output where marginal cost equals price (Q*), as long as price is greater than average variable cost at that point (in the short run), or greater than average total cost (in the long run).Figure 23. A firm will shut down temporarily if the revenue it would get from producing is less than thevariable costs of production. This occurs if price is less than average variable cost.4. A firm will exit a market if the revenue it would get if it stayed in business is less than its total cost.This occurs if price is less than average total cost.5. A firm's price equals marginal cost in both the short run and the long run. In both the short runand the long run, price equals marginal revenue. The firm should increase output as long asmarginal revenue exceeds marginal cost, and reduce output if marginal revenue is less thanmarginal cost. Profits are maximized when marginal revenue equals marginal cost.6. The firm's price equals the minimum of average total cost only in the long run. In the short run,price may be greater than average total cost, in which case the firm is making profits, or price may be less than average total cost, in which case the firm is making losses. But the situation isdifferent in the long run. If firms are making profits, other firms will enter the industry, which will lower the price of the good. If firms are making losses, they will exit the industry, which will raise the price of the good. Entry or exit continues until firms are making neither profits nor losses. At that point, price equals average total cost.7. Market supply curves are typically more elastic in the long run than in the short run. In acompetitive market, since entry or exit occurs until price equals the minimum of average total cost, the supply curve is perfectly elastic in the long run.Problems and Applications1. A competitive market is one in which: (1) there are many buyers and many sellers in the market;(2) the goods offered by the various sellers are largely the same; and (3) usually firms can freelyenter or exit the market. Of these goods, bottled water is probably the closest to a competitive market. Tap water is a natural monopoly because there's only one seller. Cola and beer are not perfectly competitive because every brand is slightly different.2. Since a new customer is offering to pay $300 for one dose, marginal revenue between 200 and 201doses is $300. So we must find out if marginal cost is greater than or less than $300. To do this, calculate total cost for 200 doses and 201 doses, and calculate the increase in total cost.Multiplying quantity by average total cost, we find that total cost rises from $40,000 to $40,401, so marginal cost is $401. So your roommate should not make the additional dose.3. a. Remembering that price equals marginal cost when firms are maximizing profit, we knowthe marginal cost must be 30 cents, since that is the price.b. The industry is not in long-run equilibrium since price exceeds average total cost.4. Once you have ordered the dinner, its cost is sunk, so it does not represent an opportunity cost.As a result, the cost of the dinner should not influence your decision about stuffing yourself.5. Since Bob’s average total cost is $280/10 = $28, which is greater than the price, he will exit theindustry in the long run. Since fixed cost is $30, average variable cost is ($280 - $30)/10 = $25, which is less than price, so Bob won’t shut down in the short run.6. Here’s the table showing costs, revenues, and profits:a. The firm should produce 5 or 6 units to maximize profit.b. Marginal revenue and marginal cost are graphed in Figure 3. The curves cross at aquantity between 5 and 6 units, yielding the same answer as in part (a).c. This industry is competitive since marginal revenue is the same for each quantity. Theindustry is not in long-run equilibrium, since profit is positive.Figure 37. a. Figure 4 shows the short-run effect of declining demand for beef. The shift of theindustry demand curve from D1 to D2 reduces the quantity from Q1 to Q2 and reduces theprice from P1 to P2. This affects the firm, reducing its quantity from q1 to q2. Before thedecline in the price, the firm was making zero profits; afterwards, profits are negative, asaverage total cost exceeds price.Figure 4b. Figure 5 shows the long-run effect of declining demand for beef. Since firms were losingmoney in the short run, some firms leave the industry. This shifts the supply curve fromS1 to S3. The shift of the supply curve is just enough to increase the price back to itsoriginal level, P1. As a result, industry output falls still further, to Q3. For firms thatremain in the industry, the rise in the price to P1 returns them to their original situation,producing quantity q1 and earning zero profits.Figure 58. Figure 6 shows that although high prices cause an industry to expand, entry into the industryeventually returns prices to the point of minimum average total cost. In the figure, the industry is originally in long-run equilibrium. The industry produces output Q1, where supply curve S1intersects demand curve D1, and the price is P1. At this point the typical firm produces output q1.Since price equals average total cost at that point, the firm makes zero economic profit.Now suppose an increase in demand occurs, with the demand curve shifting to D2. This causes "high prices" in the industry, as the price rises to P2. It also causes the industry to increase output to Q2. With the higher price, the typical firm increases its output from q1 to q2, and now makes positive profits, since price exceeds average total cost.However, the positive profits that firms earn encourage other firms to enter the industry. Their entry, "an expansion in an industry," leads the supply curve to shift to S3. The new equilibrium reduces the price back to P1, "bringing an end to high prices and manufacturers' prosperity," since now firms produce q1 and earn zero profit again. The only long-lasting effect is that industryoutput is Q3, a higher level than originally.Figure 69. a. Figure 7 shows the typical firm in the industry, with average total cost ATC1, marginal costMC1, and price P1.b. The new process reduces Hi-Tech’s marginal cost to MC2 and its average total cost to ATC2,but the price remains at P1 since other firms cannot use the new process. Thus Hi-Techearns positive profits.c. When the patent expires and other firms are free to use the technology, all firms’average-total-cost curves decline to ATC2, so the market price falls to P3 and firms earn noprofits.Figure 710. The rise in the price of petroleum increases production costs for individual firms and thus shifts theindustry supply curve up, as shown in Figure 8. The typical firm's initial marginal-cost curve is MC1 and its average-total-cost curve is ATC1. In the initial equilibrium, the industry supply curve, S1, intersects the demand curve at price P1, which is equal to the minimum average total cost of the typical firm. Thus the typical firm earns no economic profit.The increase in the price of oil shifts the typical firm's cost curves up to MC2 and ATC2, and shifts the industry supply curve up to S2. The equilibrium price rises from P1 to P2, but the price does not increase by as much as the increase in marginal cost for the firm. As a result, price is less than average total cost for the firm, so profits are negative.In the long run, the negative profits lead some firms to exit the industry. As they do so, theindustry-supply curve shifts to the left. This continues until the price rises to equal the minimum point on the firm's average-total-cost curve. The long-run equilibrium occurs with supply curve S3, equilibrium price P3, industry output Q3, and firm's output q3. Thus, in the long run, profits arezero again and there are fewer firms in the industry.Figure 811. a. Figure 9 illustrates the situation in the U.S. textile industry. With no international trade,the market is in long-run equilibrium. Supply intersects demand at quantity Q1 and price$30, with a typical firm producing output q1.Figure 9b. The effect of imports at $25 is that the market supply curve follows the old supply curve upto a price of $25, then becomes horizontal at that price. As a result, demand exceedsdomestic supply, so the country imports textiles from other countries. The typicaldomestic firm now reduces its output from q1 to q2, incurring losses, since the large fixedcosts imply that average total cost will be much higher than the price.c. In the long run, domestic firms will be unable to compete with foreign firms because theircosts are too high. All the domestic firms will exit the industry and other countries willsupply enough to satisfy the entire domestic demand.12. a. Figure 10 shows the current equilibrium in the market for pretzels. The supply curve, S1,intersects the demand curve at price P1. Each stand produces quantity q1 of pretzels, sothe total number of pretzels produced is 1,000 x q1. Stands earn zero profit, since priceequals average total cost.b. If the city government restricts the number of pretzel stands to 800, the industry-supplycurve shifts to S2. The market price rises to P2, and individual firms produce output q2.Industry output is now 800 x q2. Now the price exceeds average total cost, so each firm ismaking a positive profit. Without restrictions on the market, this would induce other firmsto enter the market, but they cannot, since the government has limited the number oflicenses.c. The city could charge a license fee for the licenses. Since it is a lump-sum fee for thelicense, not based on the quantity of sales, such a tax has no effect on marginal cost, sowon't affect the firm's output. It will, however, reduce the firm's profits. As long as thefirm is left with a zero or positive profit, it will continue to operate. So the license fee thatbrings the most money to the city is to charge each firm the amount (P2 - ATC2)q2, theamount of the firm's profit.Figure 1013. a. Figure 11 illustrates the gold market (industry) and a representative gold mine (firm).The demand curve, D1, intersects the supply curve at industry quantity Q1 and price P1.Since the industry is in long-run equilibrium, the price equals the minimum point on therepresentative firm's average total cost curve, so the firm produces output q1 and makeszero profit.b. The increase in jewelry demand leads to an increase in the demand for gold, shifting thedemand curve to D2. In the short run, the price rises to P2, industry output rises to Q2,and the representative firm's output rises to q2. Since price now exceeds average totalcost, the representative firm now earns positive profits.c. Since gold mines are earning positive economic profits, over time other firms will enter theindustry. This will shift the supply curve to the right, reducing the price below P2. Butit's unlikely that the price will fall all the way back to P1, since gold is in short supply.Costs for new firms are likely to be higher than for older firms, since they'll have to discovernew gold sources. So it's likely that the long-run supply curve in the gold industry isupward sloping. That means the long-run equilibrium price will be higher than it wasinitially.Figure 1114. a. Figure 12 shows cost curves for a California refiner and a non-California refiner. Since theCalifornia refiner has access to lower-cost oil, its costs are lower.Figure 12b. In long-run equilibrium, the price is determined by the costs of non-California refiners,since California refiners cannot supply the entire market. The market price will equal theminimum average total cost of the other refiners; they will thus earn zero profits. SinceCalifornia refiners have lower costs, they will earn positive profits, equal to (P* - ATC C) xQ C.c. Yes, there is a subsidy to California refiners that is not passed on to consumers. Thesubsidy accounts for the long-run profits of the California refiners. It arises simplybecause the oil cannot be exported.。

Chapter 8The Instruments of Trade PolicyChapter OrganizationBasic Tariff AnalysisSupply, Demand, and Trade in a Single IndustryEffects of a TariffMeasuring the Amount of ProtectionCosts and Benefits of a TariffConsumer and Producer SurplusMeasuring the Costs and BenefitsOther Instruments of Trade PolicyExport Subsidies: TheoryCase Study: Europe’s Common Agricultural PolicyImport Quotas: TheoryCase Study: An Import Quota in Practice: U.S. SugarVoluntary Export RestraintsCase Study: A Voluntary Export Restraint in Practice: Japanese Autos Local Content RequirementsBox: American Buses, Made in HungaryOther Trade Policy InstrumentsThe Effects of Trade Policy: A SummarySummaryAppendix I: Tariff Analysis in General EquilibriumA Tariff in a Small CountryA Tariff in a Large CountryAppendix II: Tariffs and Import Quotas in the Presence of Monopoly The Model with Free TradeThe Model with a TariffThe Model with an Import QuotaComparing a Tariff with a QuotaChapter 8 The Instruments of Trade Policy 33Chapter OverviewThis chapter and the next three focus on international trade policy. Students will have heard various arguments for and against restrictive trade practices in the media. Some of these arguments are sound and some are clearly not grounded in fact. This chapter provides a framework for analyzing the economic effects of trade policies by describing the tools of trade policy and analyzing their effects on consumers and producers in domestic and foreign countries. Case studies discuss actual episodes of restrictive trade practices. An instructor might try to underscore the relevance of these issues by having students scan newspapers and magazines for other timely examples of protectionism at work.The analysis presented here takes a partial equilibrium view, focusing on demand and supply in one market, rather than the general equilibrium approach followed in previous chapters. Import demand and export supply curves are derived from domestic and foreign demand and supply curves. There are a number of trade policy instruments analyzed in this chapter using these tools. Some of the important instruments of trade policy include specific tariffs, defined as taxes levied as a fixed charge for each unit of a good imported; ad valorem tariffs, levied as a fraction of the value of the imported good; export subsidies, which are payments given to a firm or industry that ships a good abroad; import quotas, which are direct restrictions on the quantity of some good that may be imported; voluntary export restraints, which are quotas on trading that are imposed by the exporting country instead of the importing country; and local content requirements, which are regulations that require that some specified fraction of a good is produced domestically.The import supply and export demand analysis demonstrates that the imposition of a tariff drives a wedge between prices in domestic and foreign markets, and increases prices in the country imposing the tariff and lowers the price in the other country by less than the amount of the tariff. This contrasts with most textbook presentations which make the small country assumption that the domestic internal price equals the world price times one plus the tariff rate. The actual protection provided by a tariff willnot equal the tariff rate if imported intermediate goods are used in the production of the protected good. The proper measurement, the effective rate of protection, is described in the text and calculated for a sample problem.The analysis of the costs and benefits of trade restrictions require tools of welfare analysis. The text explains the essential tools of consumer and producer surplus. Consumer surplus on each unit sold is defined as the difference between the actual price and the amount that consumers would have been willing to pay for the product. Geometrically, consumer surplus is equal to the area under the demand curve and above the price of the good. Producer surplus is the difference between the minimum amount for which a producer is willing to sell his product and the price which he actually receives. Geometrically, producer surplus is equal to the area above the supply curve and below the price line. These tools are fundamental to the student’s understanding of the implications of trade polici es and should be developed carefully. The costs of a tariff include distortionary efficiency losses in both consumption and production. A tariff provides gains from terms of trade improvement when and if it lowers the foreign export price. Summing the areas in a diagram of internal demand and supply provides a method for analyzing the net loss or gain from a tariff.Other instruments of trade policy can be analyzed with this method. An export subsidy operates in exactly the reverse fashion of an import tariff. An import quota has similar effects as an import tariff upon prices and quantities, but revenues, in the form of quota rents, accrue to foreign producers of the protected good. Voluntary export restraints are a form of quotas in which import licenses are held by foreign governments. Local content requirements raise the price of imports and domestic goods and do not result in either government revenue or quota rents.34 Krugman/Obstfeld •International Economics: Theory and Policy, Eighth EditionThroughout the chapter the analysis of different trade restrictions are illustrated by drawing upon specific episodes. Europe’s common agricultural policy provides and example of export subsidies in action. The case study corresponding to quotas describes trade restrictions on U.S. sugar imports. Voluntary export restraints are discussed in the context of Japanese auto sales to the United States. The oil import quota in the United States in the 1960’s provides an example of a local content scheme.There are two appendices to this chapter. Appendix I uses a general equilibrium framework to analyze the impact of a tariff, departing from the partial equilibrium approach taken in the chapter. When a small country imposes a tariff, it shifts production away from its exported good and toward the imported good. Consumption shifts toward the domestically produced goods. Both the volume of trade and welfare of the country decline. A large country imposing a tariff can improve its terms of trade by an amount potentially large enough to offset the production and consumption distortions. For a large country, a tariff may be welfare improving.Appendix II discusses tariffs and import quotas in the presence of a domestic monopoly. Free trade eliminates the monopoly power of a domestic producer and the monopolist mimics the actions of a firm in a perfectly competitive market, setting output such that marginal cost equals world price. A tariff raises domestic price. The monopolist, still facing a perfectly elastic demand curve, sets output such that marginal cost equals internal price. A monopolist faces a downward sloping demand curve under a quota.A quota is not equivalent to a tariff in this case. Domestic production is lower and internal price higher when a particular level of imports is obtained through the imposition of a quota rather than a tariff.Answers to Textbook Problems1. The import demand equation, MD, is found by subtracting the home supply equation from the homedemand equation. This results in MD= 80 - 40 ⨯P. Without trade, domestic prices and quantities adjust such that import demand is zero. Thus, the price in the absence of trade is 2.2. a. Foreign’s export supply curve, XS, is XS=-40 + 40⨯P. In the absence of trade, the price is 1.b. When trade occurs, export supply is equal to import demand, XS=MD. Thus, using theequations from Problems 1 and 2a, P= 1.50, and the volume of trade is 20.3. a. The new MD curve is 80 - 40 ⨯ (P+ t) where t is the specific tariff rate, equal to 0.5. (Note: Insolving these problems, you should be careful about whether a specific tariff or ad valorem tariff is imposed. With an ad valorem tariff, the MD equation would be expressed as MD= 80 - 40 ⨯(1 + t)P.) The equation for the export supply curve by the foreign country is unchanged. Solving,we find that the world price is $1.25, and thus the internal price at home is $1.75. The volume of trade has been reduced to 10, and the total demand for wheat at home has fallen to 65 (from thefree trade level of 70). The total demand for wheat in Foreign has gone up from 50 to 55.b. andc. The welfare of the home country is best studied using the combined numerical andgraphical solutions presented below in Figure 8.1.Figure 8.1Chapter 8 The Instruments of Trade Policy 35where the areas in the figure are:a.55(1.75 - 1.50) -0.5(55 - 50)(1.75 - 1.50) = 13.125b. 0.5(55 - 50)(1.75 - 1.50) = 0.625c. (65 - 55)(1.75 - 1.50) = 2.50d. 0.5(70 - 65)(1.75 - 1.50) = 0.625e. (65 - 55)(1.50 - 1.25) = 2.50Consumer surplus change: -(a+ b+ c+ d) =-16.875. Producer surplus change: a= 13.125.Government revenue change: c+ e= 5. Efficiency losses b+ d are exceeded by terms of tradegain e. (Note: In the calculations for the a, b, and d areas, a figure of 0.5 shows up. This isbecause we are measuring the area of a triangle, which is one-half of the area of the rectangledefined by the product of the horizontal and vertical sides.)4. Using the same solution methodology as in Problem 3, when the home country is very small relativeto the foreign country, its effects on the terms of trade are expected to be much less. The smallcountry is much more likely to be hurt by its imposition of a tariff. Indeed, this intuition is shown in this problem. The free trade equilibrium is now at the price $1.09 and the trade volume is now$36.40.With the imposition of a tariff of 0.5 by Home, the new world price is $1.045, the internal home price is $1.545, home demand is 69.10 units, home supply is 50.90, and the volume of trade is 18.20.When Home is relatively small, the effect of a tariff on world price is smaller than when Home is relatively large. When Foreign and Home were closer in size, a tariff of 0.5 by home lowered world price by 25 percent, whereas in this case the same tariff lowers world price by about 5 percent. The internal Home price is now closer to the free trade price plus t than when Home was relatively large.In this case, the government revenues from the tariff equal 9.10, the consumer surplus loss is 33.51, and the producer surplus gain is 21.089. The distortionary losses associated with the tariff (areas b+ d) sum to 4.14 and the terms of trade gain (e) is 0.819. Clearly, in this small country example, the distortionary losses from the tariff swamp the terms of trade gains. The general lesson is the smaller the economy, the larger the losses from a tariff since the terms of trade gains are smaller.5. ERP = (200 ⨯ 1.50 - 200)/100 = 100%6. The effective rate of protection takes into consideration the costs of imported intermediate goods.Here, 55% of the cost can be imported, suggesting with no distortion, home value added would be 45%. A 15% increase in the price of ethanol, though, means home value added could be as high as 60%. Effective rate of protection = (V t-V w)/V w, where V t is the value added in the presence of trade policies, and V w is the value added without trade distortions. In this case, we have (60 - 45)/45 = 33% effective rate of protection.7. We first use the foreign export supply and domestic import demand curves to determine the newworld price. The foreign supply of exports curve, with a foreign subsidy of 50 percent per unit,becomes XS=-40 + 40(1 + 0.5) ⨯P. The equilibrium world price is 1.2 and the internal foreign price is 1.8. The volume of trade is 32. The foreign demand and supply curves are used to determine the costs and benefits of the subsidy. Construct a diagram similar to that in the text and calculate the area of the various polygons. The government must provide (1.8 - 1.2)⨯ 32 = 19.2 units of output to support the subsidy. Foreign producers surplus rises due to the subsidy by the amount of 15.3 units of output. Foreign consumers surplus falls due to the higher price by 7.5 units of the good. Thus, the net loss to Foreign due to the subsidy is 7.5 + 19.2 - 15.3 = 11.4 units of output. Home consumers and producers face an internal price of 1.2 as a result of the subsidy. Home consumers surplus rises by 70 ⨯ 0.3 + 0.5 (6⨯ 0.3) = 21.9, while Home producers surplus falls by 44 ⨯ 0.3 + 0.5(6 ⨯ 0.3) =14.1, for a net gain of 7.8 units of output.36 Krugman/Obstfeld •International Economics: Theory and Policy, Eighth Edition8. a. False, unemployment has more to do with labor market issues and the business cycle than withtariff policy.b. False, the opposite is true because tariffs by large countries can actually reduce world priceswhich helps offset their effects on consumers.c. This kind of policy might reduce automobile production and Mexico, but also would increase theprice of automobiles in the United States, and would result in the same welfare loss associatedwith any quota.9. At a price of $10 per bag of peanuts, Acirema imports 200 bags of peanuts. A quota limiting theimport of peanuts to 50 bags has the following effects:a. The price of peanuts rises to $20 per bag.b. The quota rents are ($20 - $10) ⨯ 50 = $500.c. The consumption distortion loss is 0.5 ⨯ 100 bags ⨯ $10 per bag = $500.d. The production distortion loss is 0.5 ⨯ 50 bags ⨯ $10 per bag = $250.10. The reason is largely that the benefits of these policies accrue to a small group of people and thecosts are spread out over many people. Thus, those that benefit care far more deeply about these policies. These typical political economy problems associated with trade policy are probably even more troublesome in agriculture, where there are long standing cultural reasons for farmers andfarming communities to want to hold onto their way of life, making the interests even moreentrenched than they would normally be.11. It would improve the income distribution within the economy since wages in manufacturing wouldincrease, and real incomes for others in the economy would decrease due to higher prices formanufactured goods. This is true only under the assumption that manufacturing wages are lower than all others in the economy. If they were higher than others in the economy, the tariff policies would worsen the income distribution.。

经济学原理对应练习题及答案(英文版)1. T he word that comes from the Greek word for "one who managesa household" isa. market.b. consumer.c. producer.d. economy.2. T he word “economy” comes from the Greek word oikonomos,which meansa. “environment.”b. “production.”c. “one who manages a household.”d. “one who makes decisions.”3. R esources area. scarce for households but plentiful for economies.b. plentiful for households but scarce for economies.c. scarce for households and scarce for economies.d. plentiful for households and plentiful for economies.4. E conomics deals primarily with the concept ofa. scarcity.b. poverty.c. change.d. power.5. W hich of the following questions is not answered by thedecisions that every society must make?a. What determines consumer preferences?b. What goods will be produced?c. Who will produce the goods?d. Who will consume the goods?6. T he overriding reason as to why households and societies facemany decisions is that2 Chapter 1/Ten Principles of Economicsa. resources are scarce.b. goods and services are not scarce.c. incomes fluctuate with business cycles.d. people, by nature, tend to disagree.7. T he phenomenon of scarcity stems from the fact thata. most economies’production methods are not very good.b. in most economies, wealthy people consumedisproportionate quantities of goods and services.c. governments restricts production of too many goods andservices.d. resources are limited.8. A pproximately what percentage of the world's economiesexperience scarcity?a. 25%b. 50%c. 75%d. 100%9. W hen a society cannot produce all the goods and servicespeople wish to have, it is said that the economy isexperiencinga. scarcity.b. shortages.c. inefficiencies.d. inequities.10. F or society, a good is not scarce ifa. at least one individual in society can obtain all he orshe wants of the good.b. firms are producing the good at full capacity.c. all members of society can have all they want of thegood.Chapter 1/Ten Principles of Economics 3d. those who have enough income can buy all they want ofthe good.11. W hich of the following products would be considered scarce?a. golf clubsb. Picasso paintingsc. applesd. All of the above are correct.12. E conomics is the study ofa. production methods.b. how society manages its scarce resources.c. how households decide who performs which tasks.d. the interaction of business and government.14. I n most societies, resources are allocated bya. a single central planner.b. a small number of central planners.c. those firms that use resources to provide goods andservices.d. the combined actions of millions of households andfirms.15. T he adage, "There is no such thing as a free lunch," isusedto illustrate the principle thata. goods are scarce.b. people face tradeoffs.(to get something we like, weusually have to give up another thing we like)c. income must be earned.d. households face many decisions.18. W hich of the following statements best represents theprinciple represented by the adage, "There is no such thing as a free lunch"?4 Chapter 1/Ten Principles of Economicsa. Melissa can attend the concert only if she takes hersister with her.b. Greg is hungry and homeless.c. Brian must repair the tire on his bike before he can rideit to class.d. Kendra must decide between going to Colorado or Cancunfor spring break.19. T he principle that "people face tradeoffs" applies toa. individuals.b. families.c. societies.d. All of the above are correct.20. A typical society strives to get the most it can from itsscarce resources. At the same time, the society attempts to distribute the benefits of those resources to the members of the society in a fair manner. In other words, the society facesa tradeoff betweena. guns and butter.b. efficiency and equity.c. inflation and unemployment.d. work and leisure.21. G uns and butter are used to represent the classic societaltradeoff between spending ona. durable and nondurable goods.b. imports and exports.c. national defense and consumer goods.d. law enforcement and agriculture.22. W hen society requires that firms reduce pollution, there isa. a tradeoff because of reduced incomes to the firms'owners and workers.b. a tradeoff only if some firms are forced to close.Chapter 1/Ten Principles of Economics 5c. no tradeoff, since the cost of reducing pollution fallsonly on the firms affected by the requirements.d. no tradeoff, since everyone benefits from reducedpollution.23. A tradeoff exists between a clean environment and a higherlevel of income in thata. studies show that individuals with higher levels ofincome actually pollute less than low-income individuals.b. efforts to reduce pollution typically are notcompletely successful.c. laws that reduce pollution raise costs of production andreduce incomes.d. by employing individuals to clean up pollution,employment and income both rise.24. W hich of the following phrases best captures the notion ofefficiency?a. absolute fairnessb. equal distributionc. minimum wasted. equitable outcome25. W hich of the following is true?a. Efficiency refers to the size of the economic pie;equity refers to how the pie is divided.b. Government policies usually improve upon both equityand efficiency.c. As long as the economic pie continually gets larger, noone will have to go hungry.d. Efficiency and equity can both be achieved if theeconomic pie is cut into equal pieces.26. E fficiency means that6 Chapter 1/Ten Principles of Economicsa. society is conserving resources in order to save themfor the future.b. society's goods and services are distributed equallyamong society's members.c. society's goods and services are distributed fairly,though not necessarily equally, among society's members.d. society is getting the maximum benefits from its scarceresources.27. E conomists use the word equity to describe a situation inwhicha. each member of society has the same income.b. each member of society has access to abundant quantitiesof goods and services, regardless of his or her income.c. society is getting the maximum benefits from its scarceresources.d. the benefits of society's resources are distributedfairly among society's members.28. S enator Smith wants to increase taxes on people with highincomes and use the money to help the poor. Senator Jones argues that such a tax will discourage successful people from working and will therefore make society worse off. An economist would say thata. we should agree with Senator Smith.b. we should agree with Senator Jones.c. a good decision requires that we recognize bothviewpoints.d. there are no tradeoffs between equity and efficiency.29. W hich of the following words and phrases best captures thenotion of equity?a. minimum wasteb. maximum benefitChapter 1/Ten Principles of Economics 7c. samenessd. fairnessANS: D DIF: 1 REF: 1-1TOP: Equity MSC: Definitional30. W hen government policies are enacted,a. equity can usually be enhanced without an efficiencyloss, but efficiency can never be enhanced without an equity loss.b. efficiency can usually be enhanced without an equityloss, but equity can never be enhanced without an efficiency loss.c. it is always the case that either efficiency andfairness are both enhanced, or efficiency and equity are both diminished.d. None of the above are correct.ANS: D DIF: 2 REF: 1-1TOP: Government, Efficiency, Equity MSC: Applicative31. A likely effect of government policies that redistributeincome and wealth from the wealthy to the poor is that those policiesa. enhance equity.b. reduce efficiency.c. reduce the reward for working hard.d. All of the above are correct.ANS: D DIF: 2 REF: 1-1TOP: Government, Efficiency, Equity MSC: Interpretive8 Chapter 1/Ten Principles of Economics32. W hen the government implements programs such as progressiveincome tax rates, which of the following is likely to occur?a. Equity is increased and efficiency is increased.b. Equity is increased and efficiency is decreased.c. Equity is decreased and efficiency is increased.d. Equity is decreased and efficiency is decreased. ANS: B DIF:2 REF: 1-1TOP: Government, Efficiency, Equity MSC: Interpretive33. A s a result of a successful attempt by government to cut theeconomic pie into more equal slices,a. it is easier to cut the pie, and therefore the economycan produce a larger pie.b. the government can more easily allocate the pie to thosemost in need.c. the pie gets smaller, and there will be less pie overall.d. government will spend too much time cutting and itcauses the economy to lose the ability to produce enough pie for everyone.ANS: C DIF: 3 REF: 1-1TOP: Government, Efficiency, Equity MSC: Analytical34. W hen the government attempts to improve equity in an economythe result is oftena. an increase in overall output in the economy.b. additional government revenue since overall income willincrease.c. a reduction in equity.d. a reduction in efficiency.ANS: D DIF: 2 REF: 1-1TOP: Government, Efficiency, Equity MSC: InterpretiveChapter 1/Ten Principles of Economics 935. W hen the government redistributes income from the wealthy tothe poor,a. efficiency is improved, but equity is not.b. both wealthy people and poor people benefit directly.c. people work less and produce fewer goods and services.d. wealthy people consume fewer goods, but poor people consume more goods, resulting in no real change. ANS: C DIF: 2 REF: 1-1TOP: Government, Efficiency, Equity MSC: Interpretive36. I n economics, the cost of something isa. the dollar amount of obtaining it.b. always measured in units of time given up to get it.c. what you give up to get it.d. often impossible to quantify, even in principle. ANS: C DIF: 1 REF: 1-1TOP: Opportunity cost MSC: Definitional37. W hat you give up to obtain an item is called youra. opportunity cost.b. explicit cost.c. true cost.d. direct cost.ANS: A DIF: 1 REF: 1-1TOP: Opportunity cost MSC: Definitional10 Chapter 1/Ten Principles of Economics38. T he opportunity cost of going to college isa. the total spent on food, clothing, books, transportation, tuition, lodging, and other expenses.b. the value of the best opportunity a student gives up to attend college.c. zero for students who are fortunate enough to have all of their college expenses paid by someone else.d. zero, since a college education will allow a student toearn a larger income after graduation.ANS: B DIF: 2 REF: 1-1TOP: Opportunity cost MSC: Interpretive39. M aurice receives $100 as a birthday gift. In deciding how tospend the money, he narrows his options down to four choices: Option A, Option B, Option C, and Option D. Each option costs $100. Finally he decides on Option B. The opportunity cost of this decision isa. the value to Maurice of the option he would have chosenhad Option B not been available.b. the value to Maurice of Options A, C and D combined.c. $100.d. $300.ANS: A DIF: 2 REF: 1-1TOP: Opportunity cost MSC: ApplicativeChapter 1/Ten Principles of Economics 1140. A furniture maker currently produces 100 tables per week andsells them for a profit. She is considering expanding her operation in order to make more tables. Should she expand?a. Yes, because making tables is profitable.b. No, because she may not be able to sell the additionaltables.c. It depends on the marginal cost of producing more tablesand the marginal revenue she will earn from selling more tables.d. It depends on the average cost of producing more tablesand the average revenue she will earn from selling more tables.ANS: C DIF: 2 REF: 1-1TOP: Marginal changes MSC: Applicative41. F or most students, the largest single cost of a collegeeducation isa. the wages given up to attend school.b. tuition, fees, and books.c. room and board.d. transportation, parking, and entertainment.ANS: A DIF: 2 REF: 1-1TOP: Opportunity cost MSC: Interpretive12 Chapter 1/Ten Principles of Economics42. F or a college student who wishes to calculate the true costsof going to college, the costs of room and boarda. should be counted in full, regardless of the costs ofeating and sleeping elsewhere.b. should be counted only to the extent that they are moreexpensive at college than elsewhere.c. usually exceed the opportunity cost of going to college.d. plus the cost of tuition, equals the opportunity costof going to college.ANS: B DIF: 2 REF: 1-1TOP: Opportunity cost MSC: Applicative43. F or which of the following individuals would the opportunitycost of going to college be highest?a. a promising young mathematician who will command a highsalary once she earns her college degreeb. a student with average grades who has never held a jobc. a famous, highly-paid actor who wants to take time awayfrom show business to finish college and earn a degreed. a student who is the best player on his collegebasketball team, but who lacks the skills necessary to play professional basketballANS: C DIF: 2 REF: 1-1TOP: Opportunity cost MSC: ApplicativeChapter 1/Ten Principles of Economics 1344. W hen you calculate your true costs of going to college, whatportion of your room-and-board expenses should be included?a. Your full room-and-board expenses should always beincluded.b. None of your room-and-board expenses should ever beincluded.c. You should include only the amount by which yourroom-and-board expenses exceed the income you earn while attending college.d. You should include only the amount by which yourroom-and-board expenses exceed the expenses for rent and food if you were not in college.ANS: D DIF: 2 REF: 1-1TOP: Opportunity cost MSC: Applicative45. T he opportunity cost of an item isa. the number of hours needed to earn money to buy the item.b. what you give up to get that item.c. usually less than the dollar value of the item.d. the dollar value of the item.ANS: B DIF: 1 REF: 1-1TOP: Opportunity cost MSC: Definitional14 Chapter 1/Ten Principles of Economics46. M allory decides to spend three hours working overtime ratherthan watching a video with her friends. She earns $8 an hour.Her opportunity cost of working isa. the $24 she earns working.b. the $24 minus the enjoyment she would have received fromwatching the video.c. the enjoyment she would have received had she watchedthe video.d. nothing, since she would have received less than $24 ofenjoyment from the video.ANS: C DIF: 3 REF: 1-1TOP: Opportunity cost MSC: Applicative47. R ussell spends an hour studying instead of playing tennis.The opportunity cost to him of studying isa. the improvement in his grades from studying for thehour.b. the improvement in his grades from studying minus theenjoyment of playing tennis.c. the enjoyment and exercise he would have received hadhe played tennis.d. zero. Since Russell chose to study rather than to playtennis, the value of studying must have been greater than the value of playing tennis.ANS: C DIF: 3 REF: 1-1TOP: Opportunity cost MSC: ApplicativeChapter 1/Ten Principles of Economics 1548. C ollege-age athletes who drop out of college to playprofessional sportsa. are not rational decision makers.b. are well aware that their opportunity cost of attendingcollege is very high.c. are concerned more about present circumstances thantheir future.d. underestimate the value of a college education. ANS: B DIF:2 REF: 1-1TOP: Opportunity cost MSC: Interpretive49. A rational decisionmakera. ignores marginal changes and focuses instead on “thebig picture.”b. ignores the likely effects of government policies whenhe or she makes choices.c. takes an action only if the marginal benefit of thataction exceeds the marginal cost of that action.d. takes an action only if the combined benefits of thataction and previous actions exceed the combined costs of that action and previous actions.ANS: C DIF: 2 REF: 1-1TOP: Marginal changes MSC: Interpretive50. R ational people make decisions at the margin bya. following marginal traditions.b. behaving in a random fashion.c. thinking in black-and-white terms.d. comparing marginal costs and marginal benefits. ANS: D DIF: 1 REF: 1-1TOP: Marginal changes MSC: Interpretive。