FINANCE THEORY AND ACCOUNTING FRAUD

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:137.45 KB

- 文档页数:14

ADSL Asymmetrical Digital Subscriber Line 又名网络快车。

APEC Asian-Pacific Economic Cooperation 即亚太经济合作组织。

AQ Adversity Quotient逆境商数. CATV Cable Television即有线电视BBS Bulletin Board System 公告牌系统或电子公告板。

BSS Base Station System 即基站系统,指移动通信中的空中接口部分。

CARM Chinese Association of Rehabilitation Medicine即中国康复医学会。

CBD Central Business District又称中央商务区。

CCEL China Certification Committee for Environment Labelling Production即中国环境标志产品认证委员会。

CD-ROM Compact Disk-Read Only Memory即光盘只读存储器即光驱。

CEO Chief Executive Officer即首席执行官。

CET College English Test即大学英语测试。

CFO Chief Finance Officer即首席财务主管。

CI Corporate Identity即企业形象统一战略,CID Central Information District即中央信息区。

CIO Chief Information Officer即首席信息主管,也称信息中心主任。

CPA Certified Public Accountant即注册会计师CPI Consumer Price Index,即全国居民消费价格指数。

CPU Central Processing Unit又称微处理器,CS customer satisfaction 顾客满意度。

accounting and finance专业介绍-概述说明以及解释1.引言1.1 概述概述部分的内容可以包括对accounting and finance专业的定义和简要介绍。

可以着重强调该专业的重要性和它在商业领域中的作用。

概述:accounting and finance是一门研究财务管理和会计原理的学科,其目的是培养学生具备在财务和会计领域工作所需的技能和知识。

这个领域的专业人士负责管理和监督组织的财务活动,确保其财务健康并为未来的决策提供有关财务数据和信息。

会计和财务专业具有深远的影响力,无论是在商业机构还是在非营利组织。

它们为决策制定者提供了必要的财务信息,以便他们能够作出明智的决策,规划战略并管理资源。

通过学习会计和财务知识,学生将掌握财务报告、预算编制、投资决策和风险管理等方面的技能。

在现代商业环境中,会计和财务专业人士扮演着关键的角色。

他们需要具备分析能力、问题解决能力和沟通能力,以便能够理解和解释复杂的财务数据,并为管理者和其他利益相关者提供准确的报告和建议。

因此,accounting and finance专业对于那些想要在商业领域取得成功的学生来说是非常有吸引力的选择。

无论是在投资银行、会计师事务所、企业财务部门还是其他金融机构,这个专业都提供了广阔的就业机会和职业发展空间。

在接下来的章节中,我们将更详细地介绍会计专业和财务专业,以便更全面地了解这两个领域的特点和要求。

1.2 文章结构文章结构部分的内容可以描述整篇文章的组织结构和各个章节的主要内容。

可以按照以下方式编写:在本文中,将介绍accounting and finance专业的相关知识和领域。

文章主要分为引言、正文和结论三个部分。

引言部分将为读者提供一个概述,简单介绍accounting and finance 专业的背景和重要性。

同时,还会阐述本文的目的,为读者提供一个清晰的阅读指南。

正文部分将详细介绍会计专业和财务专业。

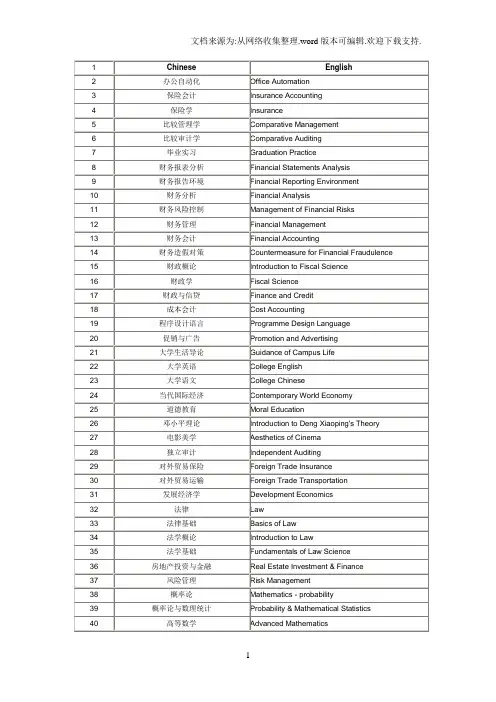

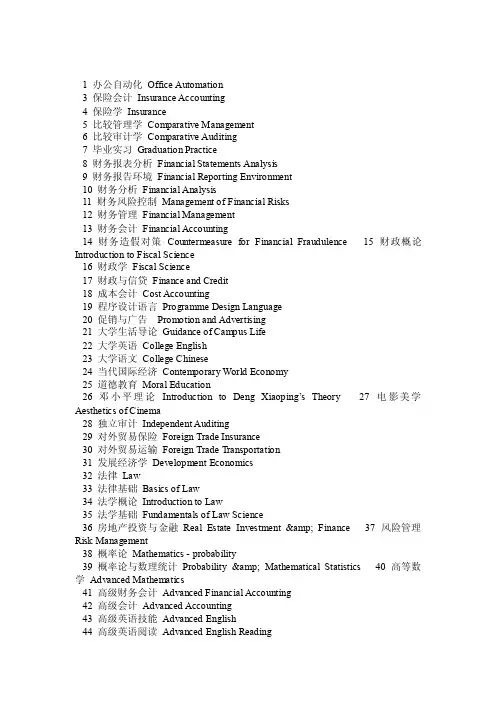

1 办公自动化Office Automation3 保险会计Insurance Accounting4 保险学Insurance5 比较管理学Comparative Management6 比较审计学Comparative Auditing7 毕业实习Graduation Practice8 财务报表分析Financial Statements Analysis9 财务报告环境Financial Reporting Environment10 财务分析Financial Analysis11 财务风险控制Management of Financial Risks12 财务管理Financial Management13 财务会计Financial Accounting14 财务造假对策Countermeasure for Financial Fraudulence 15 财政概论Introduction to Fiscal Science16 财政学Fiscal Science17 财政与信贷Finance and Credit18 成本会计Cost Accounting19 程序设计语言Programme Design Language20 促销与广告Promotion and Advertising21 大学生活导论Guidance of Campus Life22 大学英语College English23 大学语文College Chinese24 当代国际经济Contemporary World Economy25 道德教育Moral Education26 邓小平理论Introduction to Deng Xiaoping’s Theory 27 电影美学Aesthetics of Cinema28 独立审计Independent Auditing29 对外贸易保险Foreign Trade Insurance30 对外贸易运输Foreign Trade Transportation31 发展经济学Development Economics32 法律Law33 法律基础Basics of Law34 法学概论Introduction to Law35 法学基础Fundamentals of Law Science36 房地产投资与金融Real Estate Investment & Finance 37 风险管理Risk Management38 概率论Mathematics - probability39 概率论与数理统计Probability & Mathematical Statistics 40 高等数学Advanced Mathematics41 高级财务会计Advanced Financial Accounting42 高级会计Advanced Accounting43 高级英语技能Advanced English44 高级英语阅读Advanced English Reading45 高级语言程序设计Advanced Language Programme Design46 工程经济学与管理会计Engineering economics and management accounting47 工程造价管理Project Pricing Management48 工程制图Engineering Drawing49 工业会计Industrial Accounting50 工业企业管理Industrial Business Management51 工业企业经济活动分析Analysis of Industrial Business Activities52 工业行业技术评估概论Introduction to Industrial Technical Evaluation53 公共关系Public Relations54 公共金融学Public Finance55 公关礼仪Etiquette for Public Relations56 公司财务Corporate Finance57 公司法Corporate Law58 公司理财Corporate Finance59 古代诗词曲赋选讲Selections of Ancient Poems60 古代文学作品赏析Analytical Application of Ancient Literary Works61 古汉语Ancient Chinese62 股份经济学Stock Economics63 管理沟通Managerial Communication64 管理会计Management Accounting65 管理经济学Managerial Economics66 管理伦理学Business Ethics67 管理心理学Management Psychology68 管理信息Management Information69 管理信息系统Management information system70 管理学Management71 管理学原理Principle of Management72 管理战略Management Strategy73 管理咨询Business Consulting74 国际工商管理International Business Management75 国际关系与政治International Relationship and Politics76 国际会计International Accounting77 国际货物买卖合同Contract of International Goods Sales78 国际技术贸易International Technology Trade79 国际结算International Settlement80 国际金融International Finance81 国际金融市场International Financial Market82 国际经济合作概论International Economic Cooperation83 国际经济合作原理Principles of International Economic Cooperation84 国际经济组织International Economic Organizations85 国际经营管理International Business Management86 国际贸易International Trade 87 国际贸易实务International Trade Practices88 国际企业管理International Business Management。

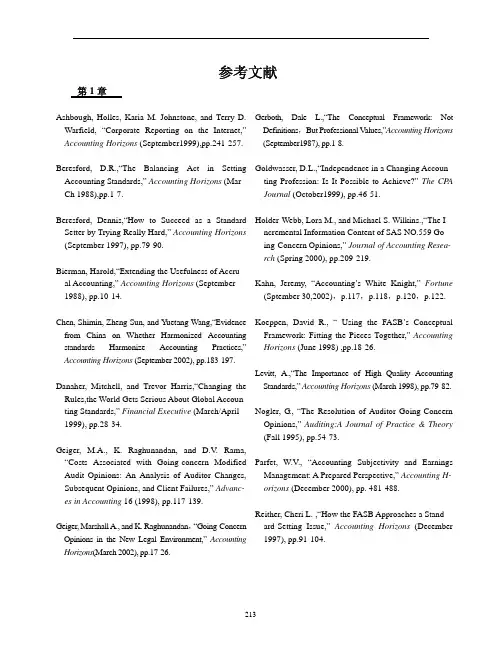

Rimerman, Thomas W. ,“The Changing Significance of Financial Statements,” Journal of Accountancy (April 1990), pp.79-183.Rogero, L.H., “Characteristics of High Quality Accounting Standards,” Accounting Horizons (June 1998), pp.177-183.Shafer, W.E.R.E. Morris, and A.A. Ketchand,“The Effects of Formal Sanctions on Auditor Independen-ce,” Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory (Su- pplement 1999), pp.85-101.Solomons, D. ,“The FASB’s Conceptual Framework: An Evaluation,” Journal of Accountancy (June 1986), pp.114-124. Stamp, Edward. “why Can Accounting Not Become aScience Like Physics?” Abacus(Spring 1981), pp.13-27.Sutton, Michael H., “Financial Reporting in U.S. CaptialMarkets: International Dimensions,” Accounting Hor-izons (June 1997), pp.96-102.Wyatt, Arthur,“Accounting Standards: Conceptual or P-olitical?” Accounting Horizons (September1990), pp.83- 88.Collett, Peter H., Jayne M. Godfrey, and Sue L. Hrasky,“International Harmonization:Cautions from the Australian Experience,” Accounting Horizons (June 2001),pp.171-182.Collins, Stephen,“The Move to Globalization,” Journal of Accountancy (March 1989), pp.82-85.Cook, J. Michael, and Michael H. Sutton, “Summary Annual Reporting: A Cure For Information Overload,” Financial Executive (January/February 1995), pp.12-25.Davidson, Ronald A., Alexander M.G. Gelardi, and Fa- ngyve Li, “Analysis of the Conceptual Framework of China’s New Accounting System,” Journal of Ac- countancy (March 1996), pp.58-74.Dye, Ronald A., and Shyam Sunder. “Why Not Allow FAST and IASB Standards to Compete in the U.S.?” Accounting Horizons (September 2001), pp.257-271.Epstein, Marc J., and Moses L. Pava, “Profile of an A- nnual Report,” Financial Executive (January/Febru- ary 1994), pp.41-43.Erickson, Merle, Brian W.Mayhew, and William L. Felix, Jr, “Why Do Audits Fail? Evidence from Lin- coln Savings and Loan,” Journal of Accounting Research (Spring 2000), pp.165-194.Firth, Michael, “Auditor-Provided Consultancy Servi- ces and Their Associations with Audit Fees and Au-dit Opinions,” Journal of Business Finance & Accou- nting (June/July 2002), pp.661-694.Hartgraves, Al L., and George J. Benston, “The Evolv-ing Accounting Standards for Special Purpose Entit- ies and Consolidations,” Accounting Horizons (September 2002), pp.245-258.Ingberman, M., and G.H. Sorter, “The Role of Financial Statements in an Efficient Market,” Journal of Acc-ounting, Auditing, & Finance (Fall 1978), pp.58-62.Lee, Charles, and Dale Morse, “Summary Annual Repor-ts,” Accounting Horizons (March 1990), pp.39-50.Lowe, Herman J., “Ethics in Our 100-Year History,” Journal of Accountancy (May 1987), pp.78-87.McEnroe, John E., and Stanley C. Martens, “Auditors’ and Investors’ Perceptions of the Expectation Gap,” Accounting Horizons (December 2001), pp.345-358.Milan, Edgar, “Ethical Compliance at Tenneco Inc.,” Management Accounting (August 1995), p.59.Millman, Gregory J., “New Scandals, Old Lessons: Financial Ethics after Enron,” Financial Executive (July/August 2002), pp.16-19.Nair, R.D., and Larry E.Rittenberg, “Summary Annual Reports: Background and Implications for Financial Reporting and Auditing,” Accounting Horizons (March 1990), pp.25-38.Perera, M.H., “Towards a Framework to Analyzing the Impact of Culture on Accounting,” International Journal of Accounting (1989), pp.42-56.Rich, Anne J., “Understanding Global Standards,”Management, Accounting (April 1995), pp.51-54.Sainty, Barbara J., Gary K. Taylor, and David D. Williams, “Investor Dissatisfaction Toward Auditors,”Journal of Accounting, Auditing, & Finance (Spring 2002), pp.111-136.Schroeder, Nicholas W., and Charles H. Gibson, “Are Summary Annual Reports Successful?” Accounting Horizons (June 1992), pp.28-37.Schroeder, Nicholas W., and Charles H. Gibson, “Improving Annual Reports by Improving the Readability of Footnotes,” The W oman CP A (April 1998),pp.13-16.Shafer, William E., D. Jordan Lowe, and Timothy J. Fogarty, “The Effects of Corporate Ownership on Public Accountants’ Professionalism and Ethics,” Accounting Horizons (June 2002), pp.109-124.W allace, R.S. Olusegun, “Survival Strategies of a Global Organization: The Case of the International Accounting Standards Committee,” Accounting Horizons(June 1990), pp.1-22.Wallace, Wanda A., and John Walsh, “Apples-to-Apples Profits Abroad,” Financial Executives (May/June 1995), pp.28-31. W ells, Joseph T., “So That’s Why It’s Called A Pyramid Scheme,” Journal of Accountancy (October 2000),pp.91-95.Wells, Joseph T., “Timing Is of the Essence,” Journal of Accountancy (May 2001), p.78; pp.81-82; pp.85-87.Wyatt, Arthur R., and Joseph F. Y ospe, “Wake-UP Call to U.S. Business: International Accounting Standards Are on the Way,” Journal of Accountancy (July 1993),pp.80-85.Zimbelman, M.F., “The Effects of SAS NO. 82 on Auditor’s Attention to Fraud Risk Factors and Audit Planning Decision,” Journal of Accounting Research (Supplement 1997), pp.75-97.Numbers That Exclude Goodwill Amortization?”Accounting Horizons (September 2001),pp.243-255.Samuelson, Richard A., “Accounting for Liabilities to Perform Services,” Accounting Horizons (September1993), pp.32-45. Sanders, George, Paul Munter, and Tommy Moures, “Software —The Unrecorded Asset,” Management Accounting (August 1994), pp.57-61.Schuetze, Walter P., “What Is an Asset?” Accounting Horizons (September 1993), pp.66-70.Earnings,” Journal of Accounting Research (Spring 2000), pp.71-102.MacDonald, Elizabeth, Accounting in the Danger Zone,”Forbes(September 2, 2002), p.138. Moses, D., “Income Smoothing and Incentives: Empirical Tests Using Accounting Changes,” The Accounting Review (April 1987), pp.358-377.Worthy, F.S., “Manipulating Profits: How It’s Done,” Fortune (June 15, 1984), pp.50-54.Ou, Jane A., and Stephen H. Penman,Financial Statement Analysis and the Prediction of Stock Returns,”Journal of Accounting and Economics (November 1989),pp.295-329.Zarowin, P., “What Determines Earnings-Price Ratios Revisited,”Journal of Accounting, Auditing, & Finance (Summer 1990),pp. 439-454.Beasley, M.S., “An Empirical Analysis of the Relation Between the Board of Director Composition and Finance Statement Fraud,” The Accounting Review (October 1996),pp. 443-465.Bell, T.B., and J.V. Carcello,“A Decision Aid for Assessing the Likelihood of Fraudulent Financial Reporting,” Auditing : A Journal of practice & Theory (Spring 1999), pp.169-184.Beneish, Messod P., “The Detection of Earnings Manipulation,” Financial Analysts Journal (September-October 1999), pp.24-36.Burgess, Deanna Qender, “Graphical Sleight of Hand,” Journal of Accountancy (February 2002), pp.45-48, p.51.Casey, C.J., Jr., “V ariation in Accounting Information Load: The Effect on Loan Officers’ Prediction of Bankruptcy,” Accounting Review (January 1980), pp.36-49.Casey, C.J., and N.J. Bartczak, “Using Operating Cash Flow Data to Predict Financial Distress: Some Extensions,” Journal of Accounting Research (Spring 1985), pp.384-401.Chandra, Uday, Bradley D. Childs, and Bturvg T. Ro, “The Association Between LIFO Reserve and Equity Risk: An Empirical Assessment,” Journal of Accounting, Auditing, & Finance (Summer 2002), pp.185-208.Dambolena, I.G., and S.J. Khorvry, “Ratio Stability and Corporate Failure,” Journal of Finance (September 1980), pp.1017-1026Dechow, P.A., R.G. Sloan, and A.P. Sweeney, “Causes and Consequences of Earnings Manipulation: An Analysis of Firms Subject to Enforcement Actions by the SEC,” Contemporary Accounting Research (Spring 1996), pp.1-36.1999), pp.757-778. Dutta, Sunil, and Frank Gigler, “The Effect of Earnings Forecasts on Earnings Management,” Journal of Accounting Research (June 2002), pp.631-656.Gombola, M.J., and J.E. Ketz , “Financial Ratio Patterns in Retail and Manufacturing Organizations,” Financial Management (Summer 1983), pp.45-56.Grent, C. Terry, Chaunrey M. Depree, Jr., and Gerry H. Grant, “Earnings Management and the Abuse of Materiality,” Journal of Accountancy (September 2000),pp. 41-44.Howell, Robert A., “Fixing Financial Reporting: Financi- al Statement Overhaul,” Financial Executive (March/ April 2002), pp.40-42.Jaggi, B., “Which Is Better, D & B or Zeta in Forecasting Credit Risk?” Journal of Business Forecasting (Summer 1984), pp.13-16, p.22.Johnson, W.B., and D.S. Dhaliwal, “LIFO Abandonment,” Journal of Accounting Research (Autumn 1988), pp.236-272.Kasznik, Ron and Maureen F.McNichols, “Does Meeting Earnings Expectations Matter? Evidence from Analyst Forecast Revisions and Share Prices,” Journal of Accouting Research (June 2002), pp.727-760.Kirschenheiter, Michael, and Nahum D. Melumad, “Can ‘Big Bath’ and Earnings Smoothing Co-exist as Equil- ibrium Financial Reporting Strategies?” Journal of Accounting Research (June 2002), pp.761-796.Largay, James A., “Lessons from Enron,” Accounting Horizons (June 2002), pp.153-156.Lennox, C.S., “The Accuracy and Incremental Information Content of Audit Reports in Predicting Bankruptcy,” Journal of Business Finance & Accounting (June/ JulyLincoln, M., “An Empirical Study of the Usefulness of Accounting Ratios to Describe Levels of Insolvency Risk,” Journal of Banking and Finance (June 1984), pp.321-340.Lynch, David, and Steven Galen, “Got the Picture? CPAs Can Use Some Simple Principles to Create Effective Charts and Graphs for Financial Reports and Presentations,” Journal of Accountancy (May 2002), pp.183-187.Makeever, D.A., “Predicting Business Failures,” The Journal of Commercial Bank Lending (January 1984), pp.14-18.McDonald, B., and M.H. Morris, “The Statistical Validity of the Ratio Method in Financial Analysis: An Empirical Examination,” Journal of Business Finance & Accounting (Spring 1984), pp.89-97.Mendenhall, Richard R., “How Naive Is the Market’s Use of Firm-Specific Earnings Information?” Journal of Accounting Research (June 2002), pp.841-864.Miller, Paul B., “Quality Financial Reporting,” Journal of Accountancy (April 2002), pp.70-74.Parsons, O., “Using Financial Statement Data to Indentify Factors Associated with Fraudulent Financial Reporting,” Journal of Applied Business Research (Summer 1995), pp.38-46.Patell, J.M., and M.A. Wolfson, “The Intraday Speed of Adjustment of Stock Prices to Earnings and Dividend Announcements,” Journal of Financial Economics (June 1984), pp.223-252.Patrone, F.L., and D. duBois, “Financial Ratios Analysis in the Small Business,” Journal of Small Business Williamson, R.W., “Evidence on the SelectiveManagement (January 1981), pp.35-40.Peterson, M., “Putting Extra Fizz into Profits; Critics Say Coca-Cola Dumps Debt on Spin Off,” New York Times (August 4, 1998), D1.Rama, D.V., K. Raghunandan, and M.A, Gerger, “The Association Between Audit Reports and Bankruptcies: Further Evidence,” Advances in Accounting 15 (1997), pp.1-15Rege, V.P., “Accounting Ratios to Locate Take-Over Targets,” Journal of Business Finance & Accounting (Autumn 1984), pp.301-311.Richardson, F.M., G.D. Kane, and P. Lobingier, “The Impact of Recession on the Prediction of Corporate Failure,” Journal of Business Finance & Accounting (January/March 1998), p.167, p.186.Shelton, Sandra Waller, O. Ray Whittington, and David Landsittel, “Auditing Firms’ Fraud Risk Assessment Practices,” Accounting Horizons (March 2001), pp.19-33.Steinbart, Paul John, “The Auditor’s Responsibility for the Accuracy of Graphs in Annual Reports: Some Evidence of the Need for Additional Guidance,” Accounting Horizons (September 1989), pp.60-70.Stober, T.L., “The Incremental Information Content of Financial Statement Disclosures: The Case of LIFO Liquidations,” Journal of Accounting Research (Supp- lement 1986), pp.138-160.Summers, S.L., and J.T. Sweeney, “Fraudulently Misstated Financial Statements and Insider Trading: An Empirical Analysis,” The Accounting Review (January 1998), pp.131-146.Tse, S., “LIFO Liquidations,” Journal of Accounting Research (Spring 1990), pp.229-238.Reporting of Financial Ratios,” The Accounting Review (April 1984), pp.296-299.Chase, Bruce, New Reporting Standards For Not-For- Profits,”Management Accounting (October 1995), pp.34-37.Chase, Bruce, W., and Laura B. Triggs, “How to Implement GASB Statement No.34,” Journal of Accountancy (November 2001), pp.71-79.Downs, G.W., and D.M. Rocke, “Municipal Budget Forecasting with Multivariate ARMA Models,” Journal of Forecasting (October-December 1983), pp.377-387.Gordon, Teresa P., Janet S. Greenlee, and Denise Nitter- house, “Tax-Exempt Organization Financial Data: Availability and Limitations,” Accounting Horizons (June 1999), pp.113-128.Hay, E., and James F. Antonio, “What Users Want In Government Financial Reports,” Journal of Accoun-tancy (August 1990), pp.91-98.Ives, Martin, “Accountability and Governmental Fina-1987), pp.130-134.Kinsman, Michael D., and Bruce Samuelson, “Personal Financial Statements: V aluation Challenges and Solutions,” Journal of Accountancy (September 1987),pp.138-148.Klasny, Edward M., and James M. Williams, “Governm-ent Reporting Faces an Overhaul,” Journal of Accoun- tancy (January 2000), pp.49-51.Meeting, David T., Randall W. Luecke, and Edward J. Giniat, “Understanding and Implementing FASB124,” Journal of Accountancy (March 1996), pp.62-66.Shoulder, Craig D., and Robert J. Freeman, “Which GAAP Should NOPs Apply?” Journal of Accountancy (November 1995), pp.77-78,p.80,p.82,p.84.Statement of Position of the Accounting Standards Division 82-1, “Accounting and Financial Reporting for Personal Financial Statements” (New York: American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, 1982).。

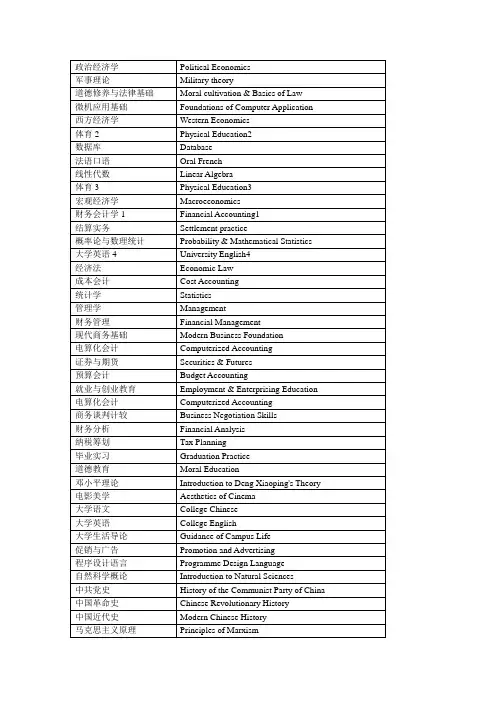

高级语言程序设计Advanced Language Programme Design工程造价管理Project Pricing Management工业行业技术评估概论Introduction to Industrial Technical Evaluation 公共关系Public Relations公关礼仪Etiquette for Public Relations管理沟通Managerial Communication国际关系与政治International Relationship and Politics国际技术贸易International Technology Trade机械制图Mechanical Drawing计算机科学Computer Science技术创新Technological Innovation技术经济Technological Economics价格学Pricing建筑项目预算Constructive Project Budgeting金融管理软件Financial Management Software经济文献检索Economic Document Searching经济文写作Economic Article Writing经贸科研论文与写作Research Project on Economics & Trade伦理学Ethics逻辑学Logic社会保障Social Security社会调查Social Survey社会学Sociology世界经济概论Introduction to World Economy世界经贸地理World Geography for Economics and Trade世界市场行情World Market Survey世界政治经济与国际关系World Politics, Economy and International Relations 数据结构Database Structure数据库管理Database Management数据库及其应用Database and Applications数据模型与决策Digital Models and Decision-making外国经济地理Economic Geography of Foreign Countries外国经济史History of Foreign Economies外贸函电Business Correspondence for Foreign Trade外贸口语Oral English for Foreign Trade外贸实务Foreign Trade Practices物流运输计划管理Logistics Planning & management系统工程System Engineering现代国际政治与经济Contemporary International Politics and Economics信息分析Information Analysis信息技术与新组织Information Technology and New Organisations形式逻辑Formal Logic英语经贸文章选读Selected English Readings of Economic and Trade Literature营销管理Marketing Management营运管理Operation Management运筹学Operations Research战略管理Strategic Management职业道德伦理Professional Ethics中国对外经贸政策与投资环境Chinese Foreign Trade Policy and Investment Environment中国对外贸易史History of Chinese Foreign Trade中国外贸概论Introduction to Chinese Foreign Trade资刊选读Selected Reading from Foreign Magazines组织行为学Organisational Behaviour大学课程英文名称(做英文成绩单有用)Advanced Computational Fluid Dynamics 高等计算流体力学Advanced Mathematics 高等数学Advanced Numerical Analysis 高等数值分析Algorithmic Language 算法语言Analogical Electronics 模拟电子电路Artificial Intelligence Programming 人工智能程序设计Audit 审计学Automatic Control System 自动控制系统Automatic Control Theory 自动控制理论Auto-Measurement Technique 自动检测技术Basis of Software Technique 软件技术基础Calculus 微积分Catalysis Principles 催化原理Chemical Engineering Document Retrieval 化工文献检索Circuitry 电子线路College English 大学英语College English Test (Band 4) CET-4College English Test (Band 6) CET-6College Physics 大学物理Communication Fundamentals 通信原理Comparative Economics 比较经济学Complex Analysis 复变函数论Computational Method 计算方法Computer Graphics 图形学原理Computer Interface Technology 计算机接口技术Contract Law 合同法Cost Accounting 成本会计Circuit Measurement Technology 电路测试技术Database Principles 数据库原理Design & Analysis System 系统分析与设计Developmental Economics 发展经济学Digital Electronics 数字电子电路Digital Image Processing 数字图像处理Digital Signal Processing 数字信号处理Econometrics 经济计量学Economical Efficiency Analysis for Chemical Technology 化工技术经济分析Economy of Capitalism 资本主义经济Electromagnetic Fields & Magnetic Waves 电磁场与电磁波Electrical Engineering Practice 电工实习Enterprise Accounting 企业会计学Equations of Mathematical Physics 数理方程Experiment of College Physics 物理实验Experiment of Microcomputer 微机实验Experiment in Electronic Circuitry 电子线路实验Fiber Optical Communication System 光纤通讯系统Finance 财政学Financial Accounting 财务会计Fine Arts 美术Functions of a Complex Variable 单复变函数Functions of Complex Variables 复变函数Functions of Complex Variables & Integral Transformations 复变函数与积分变换Fundamentals of Law 法律基础Fuzzy Mathematics 模糊数学General Physics 普通物理Graduation Project(Thesis) 毕业设计(论文)Graph theory 图论Heat Transfer Theory 传热学History of Chinese Revolution 中国革命史Industrial Economics 工业经济学Information Searches 情报检索Integral Transformation 积分变换Intelligent robot(s); Intelligence robot 智能机器人International Business Administration 国际企业管理International Clearance 国际结算International Finance 国际金融International Relation 国际关系International Trade 国际贸易Introduction to Chinese Tradition 中国传统文化Introduction to Modern Science & Technology 当代科技概论Introduction to Reliability Technology 可靠性技术导论Java Language Programming Java 程序设计Lab of General Physics 普通物理实验Linear Algebra 线性代数Management Accounting 管理会计学Management Information System 管理信息系统Mechanic Design 机械设计Mechanical Graphing 机械制图Merchandise Advertisement 商品广告学Metalworking Practice 金工实习Microcomputer Control Technology 微机控制技术Microeconomics & Macroeconomics 西方经济学Microwave Technique 微波技术Military Theory 军事理论Modern Communication System 现代通信系统Modern Enterprise System 现代企业制度Monetary Banking 货币银行学Motor Elements and Power Supply 电机电器与供电Moving Communication 移动通讯Music 音乐Network Technology 网络技术Numeric Calculation 数值计算Oil Application and Addition Agent 油品应用及添加剂Operation & Control of National Economy 国民经济运行与调控Operational Research 运筹学Optimum Control 最优控制Petroleum Chemistry 石油化学Petroleum Engineering Technique 石油化工工艺学Philosophy 哲学Physical Education 体育Political Economics 政治经济学Primary Circuit (反应堆)一回路Principle of Communication 通讯原理Principle of Marxism 马克思主义原理Principle of Mechanics 机械原理Principle of Microcomputer 微机原理Principle of Sensing Device 传感器原理Principle of Single Chip Computer 单片机原理Principles of Management 管理学原理Probability Theory & Stochastic Process 概率论与随机过程Procedure Control 过程控制Programming with Pascal Language Pascal语言编程Programming with C Language C语言编程Property Evaluation 工业资产评估Public Relation 公共关系学Pulse & Numerical Circuitry 脉冲与数字电路Refinery Heat Transfer Equipment 炼厂传热设备Satellite Communications 卫星通信Semiconductor Converting Technology 半导体变流技术Set Theory 集合论Signal & Linear System 信号与线性系统Social Research 社会调查SPC Exchange Fundamentals 程控交换原理Specialty English 专业英语Statistics 统计学Stock Investment 证券投资学Strategic Management for Industrial Enterprises 工业企业战略管理Technological Economics 技术经济学Television Operation 电视原理Theory of Circuitry 电路理论Turbulent Flow Simulation and Application 湍流模拟及其应用Visual C++ Programming Visual C++程序设计Windows NT Operating System Principles Windows NT操作系统原理Word Processing 数据处理姓名NAME性别SEX入学时间1ST TERM ENROLLED IN系别DEPARTMENT专业SPECIALITY毕业时间GRADUATION DA TE19XX-19YY学年度第一/二学期1st/2nd TERM. 19XX-19YY课程名称COURSE TITLE学分CREDIT成绩GRADE高等数学Advanced Mathematics工程数学Engineering Mathematics中国革命史History of Chinese Revolutionary程序设计Programming Design机械制图Mechanical Drawing社会学Sociology体育Physical Education物理实验Physical Experiments电路Circuit物理Physics哲学Philosophy法律基础Basis of Law理论力学Theoretical Mechanics材料力学Material Mechanics电机学Electrical Machinery政治经济学Political Economy自动控制理论Automatic Control Theory模拟电子技术基础Basis of Analogue Electronic Technique 数字电子技术Digital Electrical Technique电磁场Electromagnetic Field微机原理Principle of Microcomputer企业管理Business Management专业英语Specialized English可编程序控制技术Controlling Technique for Programming 金工实习Metal Working Practice毕业实习Graduation Practice。

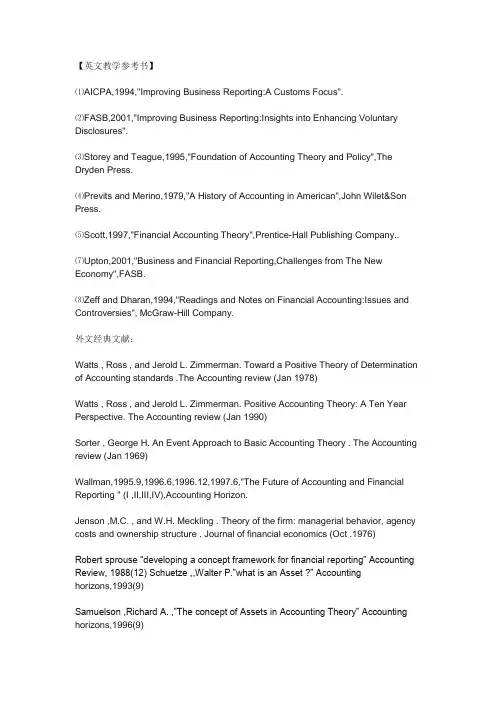

【英文教学参考书】⑴AICPA,1994,"Improving Business Reporting:A Customs Focus".⑵FASB,2001,"Improving Business Reporting:Insights into Enhancing Voluntary Disclosures".⑶Storey and Teague,1995,"Foundation of Accounting Theory and Policy",The Dryden Press.⑷Previts and Merino,1979,"A History of Accounting in American",John Wilet&Son Press.⑸Scott,1997,"Financial Accounting Theory",Prentice-Hall Publishing Company..⑺Upton,2001,"Business and Financial Reporting,Challenges from The New Economy",FASB.⑻Zeff and Dharan,1994,"Readings and Notes on Financial Accounting:Issues and Controversies", McGraw-Hill Company.外文经典文献:Watts , Ross , and Jerold L. Zimmerman. Toward a Positive Theory of Determination of Accounting standards .The Accounting review (Jan 1978)Watts , Ross , and Jerold L. Zimmerman. Positive Accounting Theory: A Ten Year Perspective. The Accounting review (Jan 1990)Sorter , George H. An Event Approach to Basic Accounting Theory . The Accounting review (Jan 1969)Wallman,1995.9,1996.6,1996.12,1997.6,"The Future of Accounting and Financial Reporting " (I ,II,III,IV),Accounting Horizon.Jenson ,M.C. , and W.H. Meckling . Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure . Journal of financial economics (Oct .1976)Robert sprouse “developing a concept framework for financial reporting” Accounting Review, 1988(12) Schuetze ,,Walter P.”what is an Asset ?” Accountinghorizons,1993(9)Samuelson ,Richard A. ,”The concept of Assets in Accounting Theory” Accounting horizons,1996(9)AAA ,”American Accounting Association on Accounting and Auditing Measurement:1989-1990” Accounting Horizons 1991(9)L.Todd Johnson and Kimberley R.Petrone “Is Goodwill an Asset?” Accounting Horizons1998(9)Linsmeier, Thomas J. and Boatsman ,Ja mes R. ,”AAA’s financial accounting standard response to IASC ED60 intangible assets” Accounting Horizons 1998(9)Linsmeier, Thomas J. and Boatsman,JamesR.”Response to IASC ExposureDraft ,’Provisions,Contingent Liabilities and Contingent Assets’ ” Accoun ting Horizons1998(6)L.Todd Johnson and Robert. Swieringa “derivatives, hedging and comprehensive income” Accounting Horizons 1996(11)Stephen A. .Zeff ,”The Rise of Economics Concequences”, The Journal of Accountancy 1978(12)David Solomons “the FASB’s Conceptual Framework:An Evaluation ” The Journal of Accountancy 1986(6)Paul Miller , “Conceptual Framework:Myths or Realities” The Journal of Accountancy 1985(3)Part I Financial Accounting TheorySuggested Bedtime Readings:1. C.J. Lee, Lecture Note on Accounting and Capital Market2. R. Watts and J. Zimmerman: Positive Accounting Theory3. W. Beaver: Revolution of Financial ReportingAlthough these three books are relatively "low-tech" in comparison with the reading assignments, but they provide much useful institutional background to the course. Moreover, these books give a good survey of accounting literature, especially in the empirical area.1. Financial Information and Asset Market Equilibrium*Grossman, S. and J. Stiglitz, "On the Impossibility of Informationally EfficientMarkets," American Economic Review (1980), 393-408.*Diamond, D. and R. Verrecchia, "Information Aggregation in a Noisy Rational Expectations Economy," Journal of Financial Economics, (1981), 221-35.*Milgrom, P. "Good News and Bad News: Representation Theorems and Applications," Bell Journal of Economics, (1981): 380-91.Grinblatt, M. and S. Ross, "Market Power in a Securities Market with Endogenous Information," Quarterly Journal of Economics, (1985), 1143-67.2. Financial Disclosure* Verrecchia, R. "Discretionary Disclosure," Journal of Accounting and Economics (1983),179-94.2Dye, R., "Proprietary and Nonproprietary Disclosure," Journal of Business, 59 (1986), 331-66.Dye, R., "Mandatory Versus Voluntary Disclosures: The Cases of Financial and Real Externalities," Accounting Review, (1990), 1-24.Bhushan, R., "Collection of Information About Public Traded Firms: Theory and Evidence," Journal of Economics and Accounting, (1989), 183-206.Diamond, D. "Optimal Release of Information by Firms," Journal of Economic Theory (1985), 1071-94.Verrecchia, R. "Information Quality and Discretionary Disclosure," Journal of Accounting and Economics, 1990.Trueman, B. "Theories of Earnings-announcement Timing," Journal of Accounting and Economics, 13 (1990), 1-17.Joh, G. and C. J. Lee "Timing of Financial Disclosure in Oligopolies," mimeo.* Joh, G. and C. J. Lee "Stock Market Reactions to Accounting Information in Oligopoly," Journal of Business, 1992.Darrough, M.N. and N.M. Stoughton, "Financial Disclosure Policy in an Entry Game," Journal of Accounting and Economics, (1990), 219-243.Wagenhofer, A. "Voluntary Disclosure with a Strategic Opponent," Journal of Accounting and Economics, 12 (1990), 341-363.Chang, C. and C.J. Lee, "Information Acquisition as a Business Strategy," Southern Economic Journal, 1992.Chang, C. and C.J. Lee, "Optimal Pricing Strategy in Marketing Research Consulting," International Economic Review, May 1994.Chang, C. and C.J. Lee, "Selling Proprietary Information to Rivaling Clients," mimeo.3. Earnings Manipulation and Accounting Choice* Watts, R. and J. Zimmerman,"Toward a Positive Theory of the Determination ofAccounting Standards," Accounting Review, January 1978, pp.112-34.*Healy, P.M. "The Effect of Bonus Schemes on Accounting Decisions" Journal of Accounting and Economics, April 1985, 85-108.*Chen, K. and C.J. Lee, "Executive Bonus Plans and Accounting Trade-off: The Case of the 3Oil and Gas Industry, 1985-86," Accounting Review, January, 1995.*Lee, C.J. and D. Hsieh, "Choice of Inventory Accounting Methods: A Test of Alternative Hypotheses," Journal of Accounting Research, Autumn 1985.*Lee, C.J. and C.R. Petruzzi, "Inventory Accounting Switch and Uncertainty", Journal of Accounting Research, Autumn 1989.*Chau, D. and C.J. Lee, “Big Bath and Dress Up in the Process of Chapter 11 Restructuring,” working paper.*Aharony, J., C.J. Lee, and T.J. Wong, “Financial Packaging of IPO Firms in China” Journal of Accounting Research, Spring 2000.Gu, Z. and C.J. Lee, “How Widespread is Earnings Management? A Measurement Based on Seasonal Heteroscedasticity.” working paperGu, Z. and C.J. Lee, “Cross-sectional Heteroscedasticity of Accounting Accruals,” working paper.Holthausen, R.W. and R.W. Leftwich, "The Economic Consequences of Accounting Choice: Implications of Costly Contracting and Monitoring," Journal of Accounting and Economics, August 1983, PP. 77-118.Moyer, S.E. "Capital Adequacy Ratio Regulations and Accounting Choices in Commercial banks," Journal of Accounting and Economics, (1990), 123-154.Blacconiere, W.G., R.M. Bowen, S.E. Sefcik, and C.H. Stinson, "Determinants of the Use of Regulatory Accounting Principles by Savings and Loans," Journal of Accounting and Economics, (1991) 167-202.Hand, J.R.M. and P.J. Hughes, and S.E. Sefcik, "Insubstance Defeasances," Journal of Accounting and Economics, (1990), 47-89.Duke, J.C. and H.G. Hunt III, "An Empirical Examination of Debt Covenant Restrictions and Accounting-Related Debt Proxies," Journal of Accounting and Economics, 12 (1990), 45-64.Malmquist, D.H., "Efficient Contracting and the Choice of Accounting Method in the Oil and Gas Industry," Journal of Accounting and Economics, 12 (1990), 173-207.Holthausen, R.W., "Accounting Method Choice: Opportunistic Behavior, Efficient Contracting, and Information Perspectives," Journal of Accounting and Economics, 12 (1990), 207-218.Watts, R. L. and J. L. Zimmerman, Positive Accounting Theory, Prentice Hall, 1985, Chapters 7-15.44. Measurement and Valuation Role of Accounting*Ball, R. and P. Brown, “Empirical Evaluation of Accounting Income Numbers,” Journal of Accounting Research, 1968.*Lee, C.J. and A. Li, “Risk, Contrarian Strategies, and Analysts’ Over-reaction: A Study of B/M and E/P Anomaly in Cross-sectional Returns.” Working Paper.Lee, C.J. "Inventory Accounting and Earnings/Price Ratios: A Puzzle," Contemporary Accounting Research, Fall, 1988.Chen, K. and C.J. Lee, "Accounting Measurement of Economic Performance and Tobin's q Theory," Journal of Accounting, Auditing, and Finance, Spring, 1995.Gu, Z. and C.J. Lee, "Co-integration and Test of Present Value Model: A Revisit," mimeo.Ghosh, A. and C.J. Lee, "Accounting Information and Market Valuation of Takeover Premium," Financial Management, Forthcoming* Joh, G. and C. J. Lee "Stock Market Reactions to Accounting Information in Oligopoly," Journal of Business, 1992.Part II Managerial Accounting5. Agency Theory*Holmstrom, B. "Moral Hazard and Observability," Bell Journal of Economics, (1979), 74-91Rogerson, "The First Order Approach to Principal-Agent Problems," Econometrica, March 1985.*Jesen, M. and W. Meckling, "Theory of the Firm, Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure," Journal of Financial Economcs, (1976), 305-60.*Grossman, S. and O. Hart, "An Analysis of the Principal-Agent Problem," Econometrica, (1983), 7-46.Holmstrom, B. "Moral Hazard in Teams," Bell Journal of Economics, (1982), 224-40.Milgrom, P. and J. Roberts, "Relying on the Information of Interested Parties," The Rand Journal of Economics, (1986), 18-32.Malcomson, J. "Rank-order Contract for a Principal with Many Agents," Review of Eonomic Studies, (1986), 807-817.Lambert, R. "Long-term Contracts and Moral Hazard," Bell Journal of Economics, (1983),5.441-452.Malcomson, J. and F. Spinnewyn, "The Multiperiod Principal-Agent Problem," Review of Economic Studies, (1988), 391-408.6. Theory of Firm and Organization*Coase, R.H. "The Nature of the Firm," Economica, (1937), 386-405.*Alchian, A.A. "Uncertainty, Evolution and Economic Theory," Journal of Political Economy,(1950), 211-21.*Alchian, A.A. and H. Demsetz, "Production, Information Costs and Economic Organization," American Economic Review, (1972), 777-795.* Sah, R. and J. Stiglitz, "The Architecture of Economic Systems: Hierarchies and Polyarchies," American Economic Review (1986), 716-727Aoki, M. "Horizontal vs. Vertical Information Structure of the Firm," American Economic Review (1986), 971-983.Tirole, J. "Hierarchies and Bureaucracies," Journal of Law, Economics and Organization (1986), 181-214.Christensen, J. "Communication in Agencies," Bell Journal of Economics, (1981), 661-674.Grossman, S. and O. Hart, "The Costs and Benefits of Ownership: A Theory of Vertical and Horizontal Integration," Journal of Political Economy, (1986), 691-719.Mookherjee, D. "Optimal Incentive Schemes with Many Agents," Review of Economic Studies (1984), 433-46.Demski, J. and D. Sappington, "Optimal Incentives with Multiple Agents," Journal of Economic Theory (1984), 152-71.Holmstrom, B. and J. Tirole, "The Theory of the Firm," in Handbook of Industrial Organization, 1990.Williamson, O. Markets and Hierarchies, 1975Williamson, O. The Economic Institution of Capitalism, 1985, Ch.6, 9, 11.7. Accounting and Internal Control*Demski, J. and D. Sappington, "Hierarchical Structure and Responsibility Accounting," Journal of Accounting Research, 1989.6*Coase, R.H., "Accounting and the Theory of Firm," Journal of Accounting and Economics, (1990), 3-13.Jordan, J., "The Economics of Accounting Information Systems," American Economic Review, 1989.Antle, R. and J. Fellingham, "Resource Rationing and Oganizational Slack in aTwo-Period Model," Journal of Accounting Research, (1990) 1-24.Demski, J., J. Patell, and M. Wolfson, "Decentralized Choice of Monitoring Systems," Accounting Review, (1984), 16-34.Penno, M. "Accounting Systems, Participation in Budgeting, and Performance Evaluation," Accounting Review, (1990), 303-314.Melumed, N.D. and S. Reichelstein, "Centralized vesus Delegation and the Value of Communication," Journal of Accounting Research, (1987 Supplement), 1-21.8. Field Studies of Management Accounting*Baiman, S., D.F. Larcker, and M.V. Rajan, "Organizational Design for Business Units," Journal of Accounting Research, 33 (Autumn 1995): 205-231.Lee, C.J. “Financial Restructuring of State-owned Enterprises in China: The Case of Shanghai Sunve Co.” Accounting, Organization and Society, fo rthcoming.Part 3. Auditing and Accounting Regulation9. Role of Auditing*R.A. Dye, B.V. Balachandran, and R.P. Magee, "Contingent Fees for Audit Firms," Journal of Accounting Research, (1990), 239-266.*L. DeAngelo, "Auditor Independence, 'Low Balling,' and Disclosure Regulation," Journal of Accounting and Economics, (1981), 113-27.*Lee, C.J. and Z. Gu, " Low Balling, Legal Liability and Auditor Independence,” Accounting Review, 1998.Magee, R.P. and M. Tseng, "Audit Pricing and Independence," Accounting Review, (1990), 315-336.Datar, S., G.A. Feltham, and J.S. Hughes, "The Role of Audits and Audit Quality in Valuing New Issues," Journal of Accounting and Economics, (1991), 3-50.7Penno, M. "Auditing for Performance Evaluation," Accounting Review, (1990),520-536.Melumad, N.D. and L. Thoman, "On Auditors and the Courts in an Adverse Selection Setting," Journal of Accounting Research, (1990) 77-120.Baiman, S., J.H. Evans III, and N.J. Nagarajan, "Collusion in Auditing," Journal of Accounting Research, (1991), 1-18.10. Financial Accounting Standards*Dye, R. and R.E. Verrecchia, "Discretion vs. Uniformity: Choices Among GAAP," Accounting Review, July 1995, 389-415.Farrell, J. and G. Saloner, "Standardization, Compatibility, and Innovation," Rand Journal of Economics. 16 (Spring 1985): 70-83.*Lev, B. "Toward a Theory of Equitable and Efficient Accounting Policy," Accounting Review, January 1988.11. The Market of CPAs*Dye, R. "Incorporation and the Audit Market," Journal of Accounting and Economics, 19 (1995): 75-114.*Lee, C.J., C. Liu, and T. Wang, “The 150 Hours Rule,” Journal of Accounting and Economics, 1999.Liu, C., C.J. Lee, and T. Wang, “Human Capital, Auditor Independence, and Legal Liability,” working paper.Riodan, M. and D. Sappington, "Information, Incentives, and Organizational Mode,"Quarterly Journal of Economics, 102 (1987): 243-264.*Gigler, F. and M. Penno, "Imperfect Competition in Audit Markets and its Effects on the Demand for Audit-Related Services," Accounting Review, 70 (April 1995):317-336.。

international review of finance and accountingThe International Review of Finance and Accounting is a peer-reviewed academic journal that focuses on research in the areas of finance and accounting. It aims to provide a platform for scholars, practitioners, and policymakers to exchange ideas and disseminate high-quality research in these fields.The journal covers a wide range of topics including corporate finance, investments, financial markets, banking, financial reporting, auditing, taxation, and other related areas. It publishes both theoretical and empirical research papers, as well as literature reviews and book reviews.The International Review of Finance and Accounting is published by Emerald Publishing and has a global readership. It is recognized as a leading journal in the field and is widely cited by researchers and professionals worldwide.The journal follows a rigorous peer-review process, ensuring the quality and validity of the published articles. It has a distinguished editorial board consisting of renowned scholars and experts in finance and accounting.Overall, the International Review of Finance and Accounting plays a significant role in advancing knowledge and understanding in the areas of finance and accounting. It provides a valuable platform for researchers and professionals to contribute to the literature and promote the development of these disciplines.。

公司金融的理论与实践:来自实地的证据关于资本成本、资本预算和资本结构问题,我们调查了392位首席财务官。

大的公司主要依靠现值技术和资本资产定价模型,而小公司相对地比较喜欢使用回收期标准。

当发行债务时,公司比较注重维护财务弹性和比较好的信用等级;当发行股票时,比较注重每股收益稀释和近期股票价格升值情况。

我们发现了对于支持优序融资假说和交易资本结构假说的支持,但是却很少找到经理关心资产替换、不对称信息、交易成本、自由现金流或者个人税务方面的证据。

关键词:资本结构资本成本股权成本资本预算折现率项目估值调查1. 简介在这篇文章中,我们对一项描述公司金融的现行实践的综合调查作了一个分析。

在这个领域中,最著名的实地研究也许就是约翰.林特纳的开创新的股利分配策略分析理论。

那个研究的结论至今仍被引用,并深刻地影响着股利分配策略的研究方式。

在很多方面,我们的目标和林特纳的有点相似。

我们的调查描述了公司金融的现行实践。

我们希望研究者们能利用我们的结果来发展新的理论—并且潜在地修改或者放弃已经存在的观点。

我们也希望从业者们能够从我们的结果中得到启发,通过观察其他的公司是怎样运行的以及确认其他学术文献没有完成的地方。

我们的调查跟以前的一些调查在很多方面都有不同。

首先,我们的调查的范围很广。

我们检测了资本配置,资本成本和资本结构。

这让我们可以把跨领域的结果联系在一起。

例如,有些公司在考虑资本结构问题时会优先考虑财务弹性,我们就调查了这些公司在考虑资本预算决定时是否也会注重实物期权。

我们在每个领域都进行了深入的探索,总共询问了100多个问题。

其次,我们抽样调查了接近4440个公司的大范围截面数据。

总计有392为首席财务官回应了我们的调查,回复率为9%。

我们所知道的第二大范围的调查是摩尔和理查特做的,调查了298个大公司。

我们研究了可能的未回复偏差,得出结论是我们的样本可以作为全部人口的代表。

第三,我们依据公司特征对回复结果进行了分析。

发表accounting and finance全文共四篇示例,供读者参考第一篇示例:财务与会计学是现代商业社会中不可或缺的重要学科,它们通过对财务数据进行分析和解释,帮助企业制定决策、评估绩效和规划未来。

在当今全球化和数字化的经济环境下,在财务与会计领域取得成功变得越来越具有挑战性和重要性。

财务与会计是紧密相关的两个学科,它们在企业管理中起着至关重要的作用。

财务是指企业运作中涉及现金流量的一切方面,包括筹措资金、投资、运营和风险管理等。

而会计是负责记录和报告企业财务活动的学科,它为决策者提供了有关企业财务状况和绩效的信息。

财务和会计的结合为企业提供了一个全面的财务管理框架,帮助企业做出明智的财务决策。

在当今竞争激烈的商业环境中,企业面临着种种挑战,如全球化竞争、技术革新、市场波动等。

在这些复杂的环境中,正确的财务与会计战略显得尤为重要。

通过高效的财务管理,企业可以优化资源利用,提高效率和生产力,实现盈利最大化。

准确的会计信息也可以帮助企业了解自身的财务状况,及时发现问题和改进不足之处。

对于个人而言,了解财务与会计知识也是非常重要的。

无论是作为企业管理者、投资者还是普通消费者,都需要具备一定的财务与会计知识来做出明智的决策。

作为企业管理者,了解财务数据可以帮助他们更好地制定战略和控制成本;而作为投资者,了解公司的财务报表可以帮助他们评估投资风险和回报;作为普通消费者,了解自己的财务状况可以帮助他们做出理性的消费决策。

财务与会计学不仅在商业领域中发挥重要作用,同时也对社会发展具有深远影响。

通过财务与会计信息的准确记录和披露,可以有效监督企业的经营活动,防止欺诈行为的发生,保护投资者和消费者的利益。

透明的财务信息也有助于政府和监管机构更好地监管和规范市场,维护金融秩序和社会稳定。

在未来,随着经济全球化和数字化的加速发展,财务与会计学将面临更多挑战和机遇。

新兴技术如人工智能、大数据、区块链等的应用将改变财务与会计领域的传统模式,为企业提供更高效、准确和安全的财务管理工具。

外文文献翻译译文一、外文原文原文:Outstanding idea: Outsourcing tradeAlong with the modern science technology's progress and the productive forces rapid development, the global competition is day by day intense, the economic globalization tendency is irresistible, in addition politics and the culture bring huge transformation, “the value chain” the concept is precisely appears under this kind of environment. it first is manages Master famous by the US the Michael ·baud in a book proposed in "Competitive advantage". Afterward soon, the value chain as well as has introduced China based on the value chain's mode of administration, should be an aspect, for our country's reform, the opening, the development make the contribution, also has provided the theory basis for enterprise's competitive advantage. Value chain introduction financial inventory accounting the domain, utilized the value chain theory the finance and accountant the aspect carries on the research only then just to emerge soon, our country at the beginning of 2004, has started a research value chain accountant's high tide. But looking from author's research, the chain and the financial strategy union conducts the research not to have nearly.The research has its necessity based on the value chain's financial strategy. In economic globalization and knowledge economy swift development today, the people observed the economic dynamics the rationale and already had the huge change to the economic activity directive, the financial tube already had developed from the profit of enterprise maximization to the enterprise value maximization, regarding the financial strategy's research should take the value as the objective point, the strategic management, the tactical management, the value chain management and the information management carried on the organic synthesis, diverted the attention to the value and the activity, management lock-on target on value chain each link The application value chain's key link is the financial outsourcing. The borderoutsourcing buyer has three famous saying: ① We to reduce the cost; ② We remain down the reason is because you have the high grade service; ③ Our investment is for own transformation and the innovation. The financial outsourcing takes one kind of outsourcing pattern to receive more and more enterprise favors, the development is rapid. The whole world well-known Market research firm IDC issue newest memoir forecast: in 2008 the global finance outsourcing market size will amount to 47,600,000,000 US dollars. The IDC research also discovered that the financial outsourcing mainly concentrated in the transaction supervisory service, the high-level fund manager's handling of traffic service and business consultant serves and so on domains, cost cutting was still the financial outsourcing outsourcing primary cause, solved the strategic business problem demand also gradually to become an important impetus finance outsourcing reason.Silent and Orr compared to (Momme and Hvolby) through to the heavy industry department's case and the behavior research, proposed the outsourcing six basic steps: The enterprise competitive power analysis, outside the contractor appraisal and the determination, the consultation and signing, the project execution and the transition, the relations manage and terminate the contract. Charles ·Gaye (Charles Gay) the research the outsourcing which mainly uses the enterprise divides into 4 patterns:①Active outsourcing;②Service outsourcing, active outsourcing and service outsourcing these two way biggest difference, if the enterprise organizes to plan to use “the service outsourcing”, itself must have the define clearly to the outsourcing demand and the goal;③Gathers package or the union outsourcing;④Interest relations outsourcing, this is one kind of long-term cooperation, both sides relates for this reason first carries on the investment, then rests on the agreement share benefit which draws up in advance.Parr and Jones (Klepper and Jones) according to the outsourcing contract nature difference, divides into three kinds the outsourcing relations:①The market outsourcing, refers to the outsourcing service is the general service which the massive outside contractors can provide;② The partner outsourcing, this figure of enterprise and the identical contractor repeatedly conclude and sign contract, and haveestablished the long-term mutually beneficial cooperation relations. In this kind of outsourcing relations, outsourcing both sides need to make in a big way, aim at this item of outsourcing relations specially the investment, the property special-purpose degree are very high.③The middle outsourcing, refers to is situated between the market and between the partner both's one kind of outsourcing relations. Three kind of relational management pattern which with the market, middle and the partner outsourcing relations correspond respectively is the market regulation pattern, the bureaucrat management pattern and the trust management pattern.The cost of financial outsourcing throughout outsourcing throughout the output. Outsourcing cost should be less than department cost cost, the department cost should be less than department create income, such outsourcing to make enterprise to create more value. For example Singapore the sea huang Oriental shipping company (hereinafter referred to as NOL) in 2003 for getting rid of the 2002 losses 3.3 billion dollars in shadow, NOL trying to save the company's cost and improve operational efficiency. In order to achieve the enterprise thin body, NOL around processing payables &receivables process basic consistent, documents of the process is not complex, it is mainly the related information through Internet relay to the regional finance, processed again teleport home so that financial outsourced will not affect the company's operations, but it can handle this part business by reduction of more than 300 employees and cost savings. Therefore NOL outsource the business to accenture, this enterprise thin body make NOL benefit, it's true purpose is to lower costs and concentrate on developing main business, raise advocate business income make oneself can have more energy to concentrate on transportation of the core business, ascension profitable space.Throughout the global Internet technology development, especially the collection, storage, retrieval, analysis, the application, the comprehensive evaluation software for enterprise financial outsourcing provides technical platform. Enterprise financial outsourcing, can use the network platform for financial information transfer. Information outsourcing program is enterprise will outsourcing bookkeeping, reimbursement, reconciliation and so on complex financial data through the networktransfer to contractors, contractors as a lot of data processing after back of enterprise general ledger system; Similarly, the bank instrument outsource all kinds of business, and also through Internet platform service providers, send to service providers to bank system processing again after. If no network technology, these data transfer only by artificially, in a long journey, information data transfer amount of frequent cases, appear low efficiency, cost is high, and existing data transmission error of risk. And outsourcing, professional organization builds a financial software, you can build scores of even hundreds of sets of account, as long as hiring a small amount of the IT staff, can guarantee routine maintenance. Outsourcing professional orgnaization financial software and hardware can fully apply, they undertake the outsourcing, the more cost is lower. Through the network technology platform, not only eliminates financial outsourcing geographically separation, still can effectively guarantee the effectiveness of business decision-making, realize the win-win situation of outsourcing organizations and enterprises.But not all corporations are applicable to outsourcing. Cheung Steven will return for outsourcing applicable enterprise chrome. ①The new businesses. Build an enterprise all aspects are imperfect, especially the internal control system of accounting system establishment must from scratch, and the set up of this system to demand higher professional technology and higher costs, build an enterprise unbearable pressure, can pass these financial outsourcing will time pressure and financial burden. Put these multifarious work outsource to the professional service agencies, both cost saving, and save time, still can achieve higher quality service; ②Business less enterprise. Some enterprise similar to automobile design industry, the annual turnover is less, have the business finance department to compare when busy, no business mostly with nothing to do. Such enterprise that often occur without living phenomenon, the idle waste of human resource, material resource again wasted, financial outsourced is to cut costs in an effective way. Still another kind is a seasonal enterprise. Seasonal enterprise "refers to a season behavior.by many, while others season and almost no portfolio, from quarter to quarter compared disparity between portfolio differ enterprise. Will the financial outsource to reduce cost, also canachieve the purpose of saving resources; ③Branch huge enterprise. This kind of enterprises in finance department has a lot of little below branch, classify, cooperatively. All kinds of business handled separately, although effective to prevent the fraud and centralization, make each branch each other between contain, but has paid a high cost price. Because division is thinner, each branch of function is different, resource utilization degree is different, so had produced redundancy branches may. The redundant branch outsourced, not only can make full use of resources to optimize configuration, still can increase efficiency, reduce the cost burden.For today's corporations, the ground is shifting. Issues such as globalisation, business efficiency, increased specialisation and product innovation are percolating upwards in priority. And corporations are now focusing more intently than ever on profitability, working capital, cash flow, technology, risk management and investments. To manage these priorities successfully, organisations are moving away from a longstanding business model. We have to break in the technical information specially the conventional model and reduced enterprise entire operation flow cost expense.Looks like New York Service Outsourcing Research institute's execution to be in chargethe American Enterprise which Frank Casale estimated in 1996 on the outsourcing, has spent 100,000,000,000 US dollars, caused its cost reduction 10%-15%. The way to break in the information the conventional model, the modern network finance outsourcing is essential. After the modern network finance outsourcing is the networking popularizes, the traditional finance outsourcing development higher form, each item of outsourcing finance function forms the organic logical relation through the networking platform, this way may also realize the overall financial function outsourcing, moreover the efficiency is high.At present, many Group interior staff function presents “a highly building redundant project tree service unit, the overhead charge to stay at a high level”, in the group as a result of the parent company and the various subsidiary companies' independent operation, basically is a separate legal entity company arranges set of troops in the financial control organization establishment. And what is more, in some group interior illegal person unit like subsidiary company, the services departmentalso has the independence financial control organization. The pattern not only scattered the financial team, raises the group overall finance level with difficulty, causes the management resources repeatedly to invest, the scale benefit which manages forms with difficulty, between the mother and child company cannot realize the resources, the information, ability sharing, cannot cause the headquarters overall plan arrangement group the financial work, moreover increased the communication cost, intensified the internal contradictions and the conflict. Therefore, concentrates the relatively simple foundational financial function, looks like the financial outsourcing to be the same, the package processes for the internal company, the establishment “the service sharing center”, establishes, transparent, the marketability, the highly effective financial control system nimbly, this will become the modern enterprise to seek in the development to use the equally important finance plan which in the near future and the financial outsourcing coordinates, to make up mutually. The financial outsourcing the financial intension which will form from this with the idea initiation achieves the industrial production management pattern before the future financial control.In the whole process of outsourcing, only after repeated thorough analysis, can cause the outsourcing activities fundamentally meet enterprise development demand, realize the transformation from inferiority to advantage, achieve financial outsourcing of various advantage. The biggest challenge is how to maintain the normal operation business does not suffer too much influence the premise, make this outsourcing can smooth transition. To complete this transition, the enterprise must consider specially for this establishment a outsourcing project office, by the chief financial officer or other significant influence enterprise member initiated and lead the process. Also cannot ignore the important factor is, want a smooth transition of another link is adjusted other personnel's communication and collaboration. When enterprise of everyone know what you are doing, why do you want to do this, outsourcing partner who is, outsourcing terms is, and what the service on the play what effect, these to establish employee to this process and outsourcing decision faith and morale is vital.Source:Miller Chaz ,2009 “Outstanding idea: Outsourcing trade”. Trade American ,vol.13,issue.4,August,pp.95-96.二、翻译文章译文:外包理念:外包贸易随着现代科学技术的进步和生产力的迅猛发展,全球竞争日益激烈,经济全球化趋势不可阻挡,加上政治和文化带来的巨大变革,“价值链”概念正是在这种环境下出现的。

高级语言程序设计Advanced Language Programme Design工程造价管理Project Pricing Management工业行业技术评估概论Introduction to Industrial Technical Evaluation 公共关系Public Relations公关礼仪Etiquette for Public Relations管理沟通Managerial Communication国际关系与政治International Relationship and Politics国际技术贸易International Technology Trade机械制图Mechanical Drawing计算机科学Computer Science技术创新Technological Innovation技术经济Technological Economics价格学Pricing建筑项目预算Constructive Project Budgeting金融管理软件Financial Management Software经济文献检索Economic Document Searching经济文写作Economic Article Writing经贸科研论文与写作Research Project on Economics & Trade伦理学Ethics逻辑学Logic社会保障Social Security社会调查Social Survey社会学Sociology世界经济概论Introduction to World Economy世界经贸地理World Geography for Economics and Trade世界市场行情World Market Survey世界政治经济与国际关系World Politics, Economy and International Relations 数据结构Database Structure数据库管理Database Management数据库及其应用Database and Applications数据模型与决策Digital Models and Decision-making外国经济地理Economic Geography of Foreign Countries外国经济史History of Foreign Economies外贸函电Business Correspondence for Foreign Trade外贸口语Oral English for Foreign Trade外贸实务Foreign Trade Practices物流运输计划管理Logistics Planning & management系统工程System Engineering现代国际政治与经济Contemporary International Politics and Economics信息分析Information Analysis信息技术与新组织Information Technology and New Organisations形式逻辑Formal Logic英语经贸文章选读Selected English Readings of Economic and Trade Literature营销管理Marketing Management营运管理Operation Management运筹学Operations Research战略管理Strategic Management职业道德伦理Professional Ethics中国对外经贸政策与投资环境Chinese Foreign Trade Policy and Investment Environment中国对外贸易史History of Chinese Foreign Trade中国外贸概论Introduction to Chinese Foreign Trade资刊选读Selected Reading from Foreign Magazines组织行为学Organisational Behaviour大学课程英文名称(做英文成绩单有用)Advanced Computational Fluid Dynamics 高等计算流体力学Advanced Mathematics 高等数学Advanced Numerical Analysis 高等数值分析Algorithmic Language 算法语言Analogical Electronics 模拟电子电路Artificial Intelligence Programming 人工智能程序设计Audit 审计学Automatic Control System 自动控制系统Automatic Control Theory 自动控制理论Auto-Measurement Technique 自动检测技术Basis of Software Technique 软件技术基础Calculus 微积分Catalysis Principles 催化原理Chemical Engineering Document Retrieval 化工文献检索Circuitry 电子线路College English 大学英语College English Test (Band 4) CET-4College English Test (Band 6) CET-6College Physics 大学物理Communication Fundamentals 通信原理Comparative Economics 比较经济学Complex Analysis 复变函数论Computational Method 计算方法Computer Graphics 图形学原理Computer Interface Technology 计算机接口技术Contract Law 合同法Cost Accounting 成本会计Circuit Measurement Technology 电路测试技术Database Principles 数据库原理Design & Analysis System 系统分析与设计Developmental Economics 发展经济学Digital Electronics 数字电子电路Digital Image Processing 数字图像处理Digital Signal Processing 数字信号处理Econometrics 经济计量学Economical Efficiency Analysis for Chemical Technology 化工技术经济分析Economy of Capitalism 资本主义经济Electromagnetic Fields & Magnetic Waves 电磁场与电磁波Electrical Engineering Practice 电工实习Enterprise Accounting 企业会计学Equations of Mathematical Physics 数理方程Experiment of College Physics 物理实验Experiment of Microcomputer 微机实验Experiment in Electronic Circuitry 电子线路实验Fiber Optical Communication System 光纤通讯系统Finance 财政学Financial Accounting 财务会计Fine Arts 美术Functions of a Complex Variable 单复变函数Functions of Complex Variables 复变函数Functions of Complex Variables & Integral Transformations 复变函数与积分变换Fundamentals of Law 法律基础Fuzzy Mathematics 模糊数学General Physics 普通物理Graduation Project(Thesis) 毕业设计(论文)Graph theory 图论Heat Transfer Theory 传热学History of Chinese Revolution 中国革命史Industrial Economics 工业经济学Information Searches 情报检索Integral Transformation 积分变换Intelligent robot(s); Intelligence robot 智能机器人International Business Administration 国际企业管理International Clearance 国际结算International Finance 国际金融International Relation 国际关系International Trade 国际贸易Introduction to Chinese Tradition 中国传统文化Introduction to Modern Science & Technology 当代科技概论Introduction to Reliability Technology 可靠性技术导论Java Language Programming Java 程序设计Lab of General Physics 普通物理实验Linear Algebra 线性代数Management Accounting 管理会计学Management Information System 管理信息系统Mechanic Design 机械设计Mechanical Graphing 机械制图Merchandise Advertisement 商品广告学Metalworking Practice 金工实习Microcomputer Control Technology 微机控制技术Microeconomics & Macroeconomics 西方经济学Microwave Technique 微波技术Military Theory 军事理论Modern Communication System 现代通信系统Modern Enterprise System 现代企业制度Monetary Banking 货币银行学Motor Elements and Power Supply 电机电器与供电Moving Communication 移动通讯Music 音乐Network Technology 网络技术Numeric Calculation 数值计算Oil Application and Addition Agent 油品应用及添加剂Operation & Control of National Economy 国民经济运行与调控Operational Research 运筹学Optimum Control 最优控制Petroleum Chemistry 石油化学Petroleum Engineering Technique 石油化工工艺学Philosophy 哲学Physical Education 体育Political Economics 政治经济学Primary Circuit (反应堆)一回路Principle of Communication 通讯原理Principle of Marxism 马克思主义原理Principle of Mechanics 机械原理Principle of Microcomputer 微机原理Principle of Sensing Device 传感器原理Principle of Single Chip Computer 单片机原理Principles of Management 管理学原理Probability Theory & Stochastic Process 概率论与随机过程Procedure Control 过程控制Programming with Pascal Language Pascal语言编程Programming with C Language C语言编程Property Evaluation 工业资产评估Public Relation 公共关系学Pulse & Numerical Circuitry 脉冲与数字电路Refinery Heat Transfer Equipment 炼厂传热设备Satellite Communications 卫星通信Semiconductor Converting Technology 半导体变流技术Set Theory 集合论Signal & Linear System 信号与线性系统Social Research 社会调查SPC Exchange Fundamentals 程控交换原理Specialty English 专业英语Statistics 统计学Stock Investment 证券投资学Strategic Management for Industrial Enterprises 工业企业战略管理Technological Economics 技术经济学Television Operation 电视原理Theory of Circuitry 电路理论Turbulent Flow Simulation and Application 湍流模拟及其应用Visual C++ Programming Visual C++程序设计Windows NT Operating System Principles Windows NT操作系统原理Word Processing 数据处理姓名NAME性别SEX入学时间1ST TERM ENROLLED IN系别DEPARTMENT专业SPECIALITY毕业时间GRADUATION DA TE19XX-19YY学年度第一/二学期1st/2nd TERM. 19XX-19YY课程名称COURSE TITLE学分CREDIT成绩GRADE高等数学Advanced Mathematics工程数学Engineering Mathematics中国革命史History of Chinese Revolutionary程序设计Programming Design机械制图Mechanical Drawing社会学Sociology体育Physical Education物理实验Physical Experiments电路Circuit物理Physics哲学Philosophy法律基础Basis of Law理论力学Theoretical Mechanics材料力学Material Mechanics电机学Electrical Machinery政治经济学Political Economy自动控制理论Automatic Control Theory模拟电子技术基础Basis of Analogue Electronic Technique 数字电子技术Digital Electrical Technique电磁场Electromagnetic Field微机原理Principle of Microcomputer企业管理Business Management专业英语Specialized English可编程序控制技术Controlling Technique for Programming 金工实习Metal Working Practice毕业实习Graduation Practice。

陈雨露、张杰、瞿强联合推荐2004-12-71、《经济学原理》N·格里高利·曼昆(N.Gregory Mankiw),中国人民大学出版社。

2、《应用经济计量学》拉姆·拉玛纳山(Ramu Ramanathan),机械工业出版社。

3、《货币金融学》弗雷德里克·S·米什金(Fredcric S.Mishkin),中国人民大学出版社。

4、《金融学》兹维·博迪、罗伯特·默顿,中国人民大学出版社。

5、《公司理财》斯蒂芬·A·罗斯,机械工业出版社。

6、《投资学精要》兹维·博迪,中国人民大学出版社。

7、《国际金融管理》Jeff.Madura,北京大学出版社。

8、《固定收入证券市场及其衍生产品》Suresh.M.Sundaresan,北京大学出版社。

9、《银行管理——教程与案例》(第五版),乔治·H·汉普尔,中国人民大学出版社。

10、《投资组合管理:理论及应用》小詹姆斯·法雷尔,机械工业出版社。

11、《衍生金融工具与风险管理》唐·M·钱斯(Don.M.Chanc),中信出版社攻读博士学位预备生精读书目陈雨露、张杰、瞿强联合推荐2004-12-71、《经济学原理》N·格里高利·曼昆(N.Gregory Mankiw),中国人民大学出版社。

2、《应用经济计量学》拉姆·拉玛纳山(Ramu Ramanathan),机械工业出版社。

3、《金融经济学》(德)于尔根·艾希贝格尔,西南财经大学出版社。

4、《货币金融学》弗雷德里克·S·米什金(Fredcric S.Mishkin),中国人民大学出版社。

5、《金融学》兹维·博迪、罗伯特·默顿,中国人民大学出版社。

6、《国际经济学》(美)保罗·克鲁德曼,中国人民大学出版社。