Law Governed Interaction (LGI) the Concept, its Implementation, and its Usage 1

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:375.71 KB

- 文档页数:83

构建公权与私权相结合的大数据技术规治体系*吴伟光(清华大学法学院副教授)内容提要数据是信息的一种载体形式,由于大数据能够被机器智能处理而产生了大数据技术。

对大数据技术的规治应该采取公权力规制和私权自治相结合的模式。

信息主体和数据主体是不同的法律主体,分别享有不同的法益。

数据主体分为数据产生和存储主体和数据分析与处理主体,他们在大数据技术规治中承担着相应的权利、义务和责任。

对大数据技术的规治要遵守六个原则,即大数据技术使用目的正当性原则、数据产生合法性原则、民事主体信息数据化平等与公平原则、数据产生主体对数据享有专有权原则、促进大数据资源共享原则和数据安全原则。

对大数据技术的法律规制应该主要通过公法路径将六个原则转变成数据主体的公法义务和责任,数据主体将公法义务和责任转化成内部的管理责任和数据主体之间依赖私权利的契约责任,形成对大数据技术的公权力规制和私权自治相互配合的局面。

关键词大数据技术大数据数据主体信息法大数据技术规治·721·*本文获得清华大学社会科学学院和数据研究院合作计划&清华大学自主科研计划文科专项经费支持。

本文中“规治”一词对应英文的“governance ”,指公权力和私权利共同规范治理。

人类因为信息而聪明,机器因为数据而智能。

大数据技术被认为将对人类社会有重大影响,其基本特征是可以将大量信息加以数据化并通过智能分析和处理来实现人类对信息使用的智能化。

大数据的生命周期可以有四步:(1)收集;(2)编辑和合并;(3)挖掘和分析;和(4)使用。

①对数据的分析最为重要,“分析使得大数据具有生命力。

没有分析,大数据可以部分或者全部地被存储或者被提取,但是其结果与最初是一样的。

分析,包括以各种不同计算技术的分析是大数据变革的推动力。

分析可以在大数据中产生新的价值,比大数据本身集合所产生的价值大得多”。

②有学者将大数据技术总结为四大能力,(1)大数据技术能够提供新形态的数据;(2)大数据技术能够提供诚实的数据;(3)大数据技术能够使得我们可以聚焦到特定人身上;以及(4)大数据技术能够使我们做很多发现因果关系的实验。

The concept of justice in sociolegal studiesPatricia EwickClark UniversityJustice is one of the most overused and underspecified concepts in the social scientific study of law. One reason for the lack of conceptual specificity is the uneasiness social scientists experience when asked to make a moral assessment of some decision, act or state of affairs. Naming and observing justice necessitates making a judgment rooted in values: Was an act or decision fair? Was it appropriate? Did it achieve some measure of justness? To engage in such assessments means we need to leave the value-free realm of so-called objective social science. Curiously- given the reluctance of social scientists to analyze justice - there seems to be general agreement that there are different sorts of justice. Often the word is preceded by an adjective connoting the various distinctions that have been drawn: procedural, substantive, and distributive. Although on the surface these qualifiers would seem to represent ever –finer distinctions of justice, they are actually evasions. Inflecting the qualifier allows us to ignore the core term (procedural justice has something to do with process, but what exactly about a process makes it just?).To avoid such epistemological exile, socio-legal scholars are much more likely to focus on justice’s evil twin: power. Unlike justice, power leaves a mark: it maims, it destroys, and (if we are to believe Foucault) it produces all sorts of things. In short it can be known by the trail it leaves and, thus, it avails itself of being observed, recorded and measured. Although I have written about – and thus must have been aware of - how social scientists tend to neglect justice by making it an understudy of power (Ewick 1997), I hadn’t fully recognized the degree to which this tendency marks my own empirical research and scholarship. For instance, in The Common Place of Law (Ewick and Silbey, 1997), the term “power,” has 17 entries (with instruction for the reader to “see also, ideology, hegemony and hierarchy”); “Resistance” has 37 entries.“Justice” does not appear in the index at all ( nor does the term “injustice”). Although this is a crude measure, it would suggest that justice has little to do with law and legality in either the legal consciousness of ordinary citizens or the imagination of sociolegal scholars.More recently, I have been studying a chapter of Voice of the Faithful, an international organization of faithful Catholics who formed after the sex scandal in order to bring about structural change in the Church (empowering the laity) and to support the victims of clergy sex abuse. In light of the group’s outrage at the scandal, and especially at the complicity of the Church hierarchy, I expected that notions of justice and injustice would be a central part of their experience and discourse. Yet, much like the citizens of NewJersey, members of VOTF are strangely silent on the subject of justice - expressing anger, hurt, outrage, betrayal, but rarely a sense of injustice.What, then, are we to make of this preoccupation with power? Is it merely epistemological? How are we to explain the relative infrequency with which people (who are not as wedded to positivist social science as social scientists of law might be) employ a discourse of justice?I have elsewhere theorized the relationship between justice and power as mutually constitutive. This relationship, moreover, offers a possible clarification of the eclipse of justice in both our understanding of law and the absent discourse about justice/injustice among citizens. Typically justice is thought of as external from legal power, functioning to demarcate the limits of such power by specifying standards against which it can be held accountable or by offering ideals that law does not yet embody. By contrast, I have proposed that justice and power stand in a dialectical relationship to one another. Conceptions of justice, in other words, catalyze, rather than simply contain power. Justice calls forth power; it demands actions as much as it limits it. Moreover, to the extent that conceptions of justice are historical constructions, whose articulation and acceptance needs to be explained, power is implicated in the construction of justice. In other words, just as the exercise of legal power is constituted by conceptions of justice, cultural understandings of justice are likewise defined by the power against which they are poised. This conceptualization invites us to examine the dynamic, historical processes through which power and justice operate and the sorts of misrecognitions that might result.Recently, for instance, I explored this process in an essay entitled “The Scale of Injustice” (2009). The essay examines transformation in the operation of power that make the recognition of injustice increasingly difficult. In the contemporary world of neoliberal law, hyper-rationalized governance, and global economies, power often operate from a distance and yet, at the same time, through finer circuitries of social life. In this world, individuals are part of shifting and overlapping networks rather than role-based relationships. Law exists at multiple, parallel planes. As a result, injustices often occur from a distance and, simultaneously, at a smaller scale. Responsibility for redressing systemic harms is shifting and vague. Woven into markets and bureaucracies, embedded into protocols and standard operating procedures, the scope of injustice is wide and deep. Such injustices are frequent, systemic and impersonal. Their consequences are often erosive rather than violent, they are cumulative rather than singular. In other words, as the scalar resolution of power shifts, the ability to apprehend its operation from the ground of everyday life diminishes. Finally, because it becomes increasingly difficult to name an event as unjust, to attribute agency or motive, or even calculate injury, these mundane injustices often go unrecognized and thus unnamed, although not unfelt. Perhaps our preoccupation with power (and correlative neglect of justice) , then, can be traced to the thing itself. Globalization and what Foucault has called governmentality have seemingly effaced power by removing it from the “here” and “now.” The apparent evacuation of power from everyday life inhibits the naming of injustice insofar as theincommensurability between the scale at which injuries are felt and the scale at which power operates incapacitates the sorts of ideological revisions that activate a sense of injustice.。

第25卷第12期河北法学V ol.25,No.122007年12月Hebei L aw ScienceDec .,2007国际商事合同中法律规避与意思自治的制约与权衡王 慧收稿日期:2007208228作者简介:王 慧(19582),女,天津人,北京大学法学院党委委员,副教授,国际经济法专业硕士研究生导师、导师组组长,研究方向:国际经济法学。

(北京大学法学院,北京100871)摘 要:在国际商事合同的准据法的确定问题上,当事人意思自治原则是各国及国际公约公认的首要原则。

但在理论上及有些国家的立法中,对当事人意思自治还有一些不合理的限制,其中包括要求当事人所选择的法律必须与合同有实际联系。

当事人通过改变或创设连结点的方式以使其合同表面符合有“实际联系”的要求,被认为构成国际私法上的法律规避。

对此问题的澄清有利于正确认识国际私法各种制度存在的价值。

通过分析得出,意思自治原则承认当事人有选择法律的自由,就等于接受了当事人有权规避某一国法律的事实。

当事人规避“实际联系”并未侵害法律所保护的正当利益。

国际私法不能用“实际联系”来限制当事人选择合同准据法的自由。

关键词:国际商事合同;意思自治;实际联系;法律规避中图分类号:DF961 文献标识码:A 文章编号:100223933(2007)1220117204On R estriction and B alance bet w een Evasion of La wand Autonomy of Will in International Commercial ContractsWAN G Hui(Law School ,Peking University ,Beijing 100871China )Abstract :As to ascertaining the governing law applicable to the international commercial contracts ,the rule of autonomy of will isthe primary principle widely accepted by both domestic laws of most countries and international treaties.However ,in theory as well as the legislation of some countries ,there are still some unreasonable restrictions on the rule of autonomy of will ,including the requirement of substantial connection between the law chosen by the parties and the contract.It is deemed to be the evasion of law that the parties make their contract meet the requirement of “substantial connection ”ostensibly by way of changing or establishing the connecting point.Clarification concerning this issue helps with understanding the value of various mechanisms in private international law.After analysis ,a conclusion can be drawn that the parties ’freedom to choose governing law itself indicates the parties ’rights to evade the law of a country.Evasion of substantial connection does not damage the legitimate interests protected by law.Private international law shall not restrict the parties ’freedom to choose governing law of contract with the substantial connection theory.K ey w ords :international commercial contract ;autonomy of will ;substantial connection ;evasion of law 在国际民事领域,法律规避的现象比较普遍,从法律规避现象最早出现在亲属法领域开始,现已扩展到国际民商事交往的各个领域,其中法律规避与国际商事合同中当事人选择合同准据法的意思自治原则又存在着某种关联。

Law of the People's Republic of China on Application of Laws toForeign-Related Civil RelationsPromulgating Institution: Standing Committee of the National People's CongressDocument Number: Order No. 36 of the President of the People's Republic of China Promulgating Date: 10/28/2010Effective Date: 04/01/2011Validity Status: ValidOrder No. 36 of the President of the People's Republic of ChinaThe Law of the People's Republic of China on Application of Laws to Foreign-Related Civil Relations, adopted on October 28, 2010 at the 17th session of the Standing Committee of the 11th National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China, is hereby promulgated and shall come into effecton April 1, 2011.President of the People's Republic of China Hu JintaoOctober 28, 2010 Law of the People's Republic of China on Application of Laws to Foreign-Related Civil Relations (Adopted at the 17th session of the Standing Committee of the 11th National People's Congress onOctober 28, 2010)Table of ContentsChapter 1 General ProvisionsChapter 2 Civil SubjectsChapter 3 Marriage and FamilyChapter 4 SuccessionChapter 5 Property RightsChapter 6 Creditor's RightsChapter 7 Intellectual Property RightsChapter 8 Supplementary ProvisionsChapter 1 General ProvisionsArticle 1 This Law is formulated with a view to specifying the application of laws to foreign-related civil relations, resolving foreign-related civil disputes in a reasonable manner, and safeguarding the legitimate rights and interests of the parties concerned.Article 2 Laws applicable to foreign-related civil relations shall be determined in accordance with this Law. Provisions on the application of laws to foreign-related civil relations otherwise prescribed in other laws shall prevail.In the absence of provisions on the application of laws to foreign-related civil relations as prescribed in this Law and other laws, laws having the most significant relationship with the foreign-related civil relation in question shall apply.Article 3 Parties concerned may, in accordance with the law, expressly choose laws applicable to foreign-related civil relations.Article 4 Mandatory provisions on foreign-related civil relations prescribed in laws of the People's Republic of China shall directly apply.Article 5 Laws of the People's Republic of China shall apply where the application of foreign laws will undermine social and public interests of the People's Republic of China.Article 6 In the event that laws of a given foreign country apply to the foreign-related civil relation inquestion, if different regions of the foreign country are governed by different laws, laws of the region having the most significant relationship with the foreign-related civil relation shall apply.Article 7 Limitations shall be governed by the laws applicable to the foreign-related civil relation in question.Article 8 Lex fori shall apply in determining the nature of foreign-related civil relations.Article 9 Foreign laws applicable to foreign-related civil relations shall not include laws on the application of laws of the foreign countries.Article 10 Foreign laws applicable to foreign-related civil relations shall be ascertained by people's courts, arbitration commissions or administrative organs. Parties concerned shall provide laws of the relevant foreign country if they choose to be governed by foreign laws.In the event that foreign laws are unable to be ascertained or contain no relevant provisions, laws of the People's Republic of China shall apply.Chapter 2 Civil SubjectsArticle 11 The capacity for civil rights of natural persons shall be governed by laws of their habitual residence.Article 12 The capacity for civil conduct of natural persons shall be governed by laws of their habitual residence.In the event that a natural person engages in civil activities, where he/she has no civil conduct capacity in accordance with the laws of the habitual residence but has such capacity in accordance with lex loci actus, the latter shall prevail, except for matters relating to marriage, family and succession.Article 13 Where a natural person is to be declared missing or dead, laws of the habitual residence of the natural person shall apply.Article 14 Laws of the registration place shall apply to the capacity for civil rights, capacity for civil conduct, organizational structure, shareholders' rights and obligations and other matters of a legal person and the branch offices thereof.Where the place of principal office of a legal person is different from its place of registration, laws of the place of principal office may apply. The habitual residence of a legal person shall be its place of principal office.Article 15 Contents of the rights of personality shall be governed by laws of the habitual residence of the right holder.Article 16 Agency shall be governed by lex loci actus, provided that the civil relation between the principal and the agent shall be governed by laws of the place of occurrence of the agency relationship. Parties concerned may choose laws applicable to entrustment and agency by agreement.Article 17 Parties concerned may choose laws applicable to trust by agreement. Where the parties have made no such choice, lex rei sitae of the trust property or laws of the place of occurrence of the trust relationship shall apply.Article 18 Parties concerned may agree upon the laws applicable to an arbitration agreement. Where the parties have made no such choice, laws of the domicile of the arbitration commission or laws of the place of arbitration shall apply.Article 19 In the event that lex patriae applies in accordance with this Law, where a natural person has two (2) or more nationalities, lex patriae of the country with his/her habitual residence shall apply; where no country of nationality has his/her habitual residence, lex patriae of the country having themost significant relationship with him/her shall apply. In the case of stateless natural persons or natural persons without clear nationality, laws of their habitual residence shall apply.Article 20 In the event that laws of the habitual residence shall apply in accordance with this Law, and that the habitual residence of a natural person is unclear, laws of his/her current residence shall apply.Chapter 3 Marriage and FamilyArticle 21 Conditions for marriage shall be governed by laws of the common habitual residence of both parties concerned. In the absence of a common habitual residence, common lex patriae of the parties shall apply. Where the parties are of different nationalities, and the parties get married in the habitual residence or country of nationality of either party, laws of the place of marriage shall apply.Article 22 Formalities for marriage shall be valid if they are in compliance with the laws of the place of marriage, or the laws of the habitual residence or lex patriae of either party.Article 23 Matrimonial personal relationship of a couple shall be governed by laws of their common habitual residence. In the absence of a common habitual residence, the common lex patriae of the couple shall apply.Article 24 Matrimonial property relationship of a couple may be governed by laws of the habitual residence or lex patriae of either party, or lex rei sitae of major properties, as chosen by the couple upon agreement. Where the couple have made no such choice, laws of their common habitual residence shall apply. In the absence of a common habitual residence, the common lex patriae of the couple shall apply. Article 25 Personal and property relationship between parents and children shall be governed by laws of their common habitual residence. In the absence of a common habitual residence, laws of the habitual residence or lex patriae of a party concerned that favors the rights and interests of the weak shall apply.Article 26 In the event of an uncontested divorce, the couple concerned may choose to apply laws of the habitual residence or lex patriae of either party. Where the couple have made no such choice, laws of their common habitual residence shall apply. In the absence of a common habitual residence, the common lex patriae of the couple shall apply. Where the couple are of different nationalities, laws of the place where the agency handling the divorce formalities is located shall apply.Article 27 In the case of a contested divorce, lex fori shall apply.Article 28 Conditions and formalities for adoption shall be governed by both the laws of the habitual residence of the adopter and the laws of the habitual residence of the adoptee. The validity of adoption shall be governed by laws of the habitual residence of the adopter at the time of adoption. Termination of the adoptive relationship shall be governed by lex fori or laws of the habitual residence of the adoptee at the time of adoption.Article 29 Dependence shall be governed by laws of the habitual residence or lex patriae of either party or lex rei sitae of major properties that favors the rights and interests of the dependent.Article 30 Guardianship shall be governed by laws of the habitual residence or lex patriae of either party that favors the rights and interests of the ward.Chapter 4 SuccessionArticle 31 Statutory succession shall be governed by laws of the habitual residence of the decedent at the time of death, provided that statutory succession to real properties shall be governed by lex situs of the properties.Article 32 In the case of succession ex testamento, a will shall be valid if it is in compliance with laws of the habitual residence or lex patriae of the testator or lex loci actus of will creation at the time of death or will creation.Article 33 The validity of a will shall be governed by laws of the habitual residence or lex patriae of the testator at the time of death or will creation.Article 34 Matters relating to the administration of estate shall be governed by lex rei sitae of the estate.Article 35 The ownership of estate left with no successor shall be governed by lex rei sitae of the estate at the time of death of the decedent.Chapter 5 Property RightsArticle 36 Property rights of real properties shall be governed by lex situs.Article 37 Parties concerned may choose the laws applicable to property rights of movable properties by agreement. Where the parties have made no such choice, lex rei sitae of the movable properties at the time of occurrence of the legal incident shall apply.Article 38 Parties concerned may agree upon the laws applicable to the change of property rights of movable properties during transport. Where the parties have made no such choice, laws of the transport destination shall apply.Article 39 In the case of marketable securities, laws of the place of realization of the rights of such securities or other laws having the most significant relationship with the securities shall apply. Article 40 Pledge of rights shall be governed by laws of the place where the pledge is instituted.Chapter 6 Creditor's RightsArticle 41 Parties concerned may choose the laws applicable to a contract by agreement. Where the parties have made no such choice, laws of the habitual residence of the party whose performance of obligations best reflects the characteristics of the contract or other laws having the most significant relationship with the contract shall apply.Article 42 A consumer contract shall be governed by laws of the habitual residence of the consumer. Where the consumer chooses to apply laws of the place where the goods or services are provided, or the business operator concerned does not engage in relevant business activities at the habitual residence of the consumer, laws of the place where the goods or services are provided shall apply.Article 43 A labor contract shall be governed by laws of the work place of the laborer. Where it is difficult to determine the work place of the laborer, laws of the place of principal office of the employer shall apply. Labor dispatch services may be governed by laws of the place of dispatch.Article 44 Tort liabilities shall be governed by lex loci delicti, provided that where the parties concerned have a common habitual residence, laws of the common habitual residence shall apply. Agreements on the application of laws reached by the parties concerned after the occurrence of tort shall prevail.Article 45 Product liabilities shall be governed by laws of the habitual residence of the infringed party. Where the infringed party chooses to apply laws of the place of principal office of the infringer or lex loci delicti, or the infringer does not engage in relevant business activities at the habitual residence of the infringed party, laws of the place of principal office of the infringer or lex loci delicti shall apply.Article 46 Infringement on the right of name, portrait, reputation or privacy or other rights of personality via the Internet or by other means shall be governed by laws of the habitual residence of the infringed party.Article 47 In the case of unjust enrichment and negotiorum gestio, laws chosen by the parties concerned by agreement shall apply. Where the parties have made no such choice, laws of the common habitual residence of the parties shall apply. In the absence of a common habitual residence, laws of the place of unjust enrichment or negotiorum gestio shall apply.Chapter 7 Intellectual Property RightsArticle 48 The ownership and contents of an intellectual property right shall be governed by laws of the place where protection is claimed.Article 49 Parties concerned may choose the laws applicable to the transfer and user-licensing of intellectual property rights by agreement. Where the parties have made no such choice, provisions on contracts herein shall apply.Article 50 Liabilities for infringement upon intellectual property rights shall be governed by laws of the place where protection is claimed. Parties concerned may also choose to apply lex fori by agreement after occurrence of the infringement.Chapter 8 Supplementary ProvisionsArticle 51 In the event of any discrepancy between this Law and Article 146 and Article 147 of the General Principles of the Civil Law of the People's Republic of China, as well as Article 36 of the Law of Succession of the People's Republic of China, this Law shall prevail.Article 52 This Law shall come into effect on April 1, 2011.。

国际私法期末考试知识点整理名词解释1:间接调整方法(Indirect adjustment method).所谓间接调整方法,就是在有关的国内法和国际条约中规定某类国际民商事关系应受何种法律支配或调整,而不是直接规定民商事关系当事人权利与义务关系的方法,即通过冲突规范来调整国际民商事关系,它是国际私法的特有调整方法。

2(@):法域,英文为law district, legal unit, legal region, territorial legal unit等多种表达法,是指适用独特法律制度的特定范围。

这个特定的范围既可能是空间范围,又可能是成员范围,还可能是时间范围。

正是基于此,法域有属地性法域、属人性法域和属时性法域之分。

3:法人(legal person)是指按照法定程序设立,有一定的组织机构和独立的财产,并能以自己的名义享有民事权利和承担民事义务的社会组织。

4:识别(qualification,classification,characterization)识别也称为定性或分类,是指法院在适用冲突规范时,依据一定的法律观念,对有关的事实构成作出定性或分类,将其归入特定的法律范畴,并对有关冲突规范所使用的名词进行解释,从而确定应适用的冲突规范的认识过程。

5: 反致(renvoi)广义的反致包括狭义的反致(remission)、转致、间接反致和外国法院说。

狭义的反致是对某一涉外民商事案件,法院按照法院地的冲突规则本应适用外国法,但外国法中的冲突规则指定适用法院地法,如果法院接受这种指定并适用法院地法,这种现象就叫做反致。

转致(transmissin):是指对某一国际私法案件,甲国法院按照本国的冲突规范本应适用乙国法,乙国的冲突规范又指定适用丙国法,甲国法院因此适用了丙国实体法。

转致在法文中称为“二级反致”。

间接反致:是指对某一国际私法案件,甲国法院依本国的冲突规范应适用乙国法,依乙国的冲突规范又适用于丙国法,依丙国的冲突规范确适用于甲国法,甲国法院因此适用本国的实体法作为准据法。

《涉外民事关系法律适用法》英文作者:陈卫佐等STATUTE ON THE APPLICATION OF LAWS TO CIVIL RELATIONSHIPS INVOLVING FOREIGN ELEMENTS OF THEPEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA(ADOPTED BY THE 17th SESSION OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE OF THE ELEVENTH NATIONAL PEOPLE’S CONGRESS ON 28 OCTOBER 2010)Translation by CHEN Weizuo* and Kevin M. MOORE** ContentsChapter I General ProvisionsChapter II Civil SubjectsChapter III Marriage and FamilyChapter IV SuccessionChapter V Rights in RemChapter VI ObligationsChapter VII Intellectual Property RightsChapter VIII Supplementary ProvisionsChapter I General ProvisionsArticle 1 The present Statute is enacted in order to clarify the application of laws to civil relationships involving foreign elements, to resolve civil disputes involving foreign elements in an equitable manner, and to safeguard the lawful rights and interests of parties.Article 2 The law applicable to civil relationships involving foreign elements shall be determined in accordance with the present Statute. If other statutes contain special provisions on the application of laws to civil relationships involving foreign elements, those provisions shall prevail.If the present Statute or other statutes contain no provisions with regard to the application of laws to civil relationships involving foreign elements, the law that has the closest connection with the civil relationship involving foreign elements shall be applied.Article 3 In accordance with statutory provisions, the parties may expressly choose the law applicable to a civil relationship involving foreign elements.Article 4 If the law of the People’s Republic of China contains mandatory rules on civil relationships involving foreign elements, those mandatory rules shall be applied directly.Article 5 If the application of a foreign law would cause harm to social and public interests of the People’s Republic of China, the law of the People’s Republic of China shall be applied.Article 6 If a civil relationship involving foreign elements is to be governed by foreign law, and if different regions in the foreign country have different laws in force, the law of the region with which the civil relationship involving foreign elements has the closest connection shall be applied.Article 7 Limitation of actions shall be governed by the law that is to govern the relevant civil relationship involving foreign elements.Article 8 The characterization of any civil relationship involving foreign elements shall be governed by the lex fori.Article 9 The law of a foreign country that is to govern a civil relationship involving foreign elements does not refer to the law on the application of laws of that country.Article 10 The law of a foreign country that is to govern a civil relationship involving foreign elements shall be ascertained by the people’s courts, arbitration institutions or administrative organs.If the law of a foreign country cannot be ascertained, or if the law of that country contains no relevant provisions, the law of the People’s Republic of China shall be applied.Chapter II Civil SubjectsArticle 11 The civil legal capacity of a natural person shall be governed by the law of the place of his/her habitual residence.Article 12 The capacity to engage in civil juristic acts of a natural person shall be governed by the law of the place of his/her habitual residence.If a natural person is engaged in civil activities, and he/she has no capacity to engage in civil juristic acts according to the law of the place of his/her habitual residence, but he/she has the capacity to engage in civil juristic acts according to the lex loci actus, the lex loci actus shall be applied, except if marriage, family or succession is involved.Article 13 Declaration of a missing person or declaration of death shall be governed by the law of the place of habitual residence of the natural person concerned.Article 14 Matters such as the civil legal capacity, the capacity to engage in civil juristic acts, organizations and institutions of a legal person and its branches, as well as shareholders’ rights and duties, shall be governed by the law of the place of registration.If the principal place of business of a legal person differs from the place of registration, the law of the principal place of business may be applied. The place of habitual residence of a legal person is its principal place of business.Article 15 Contents of rights of personality shall be governed by the law of the place of habitual residence of the right holder.Article 16 Agency shall be governed by the lex loci actus of the act of agency, but civil relationships between the principal and the agent shall be governed by the law of the place where the agency relationship occurs.The parties may choose by agreement the law applicable to an entrusted agency.Article 17 The parties may choose by agreement the law applicable to a trust. In the absence of a choice by the parties, the law of the place where the trust property is situated or the law of the place where the trust relationship occurs shall be applied.Article 18 The parties may choose by agreement the law applicable to an arbitration agreement. In the absence of a choice by the parties, the law of the place where the arbitration institution is situated or the law of the place of arbitration shall be applied.Article 19 If the law of the country of nationality is to be applied according to the present Statute, and a natural person has two or more nationalities, the law of the country of nationality in which he/she has a habitual residence shall be applied; if he/she has no habitual residence in any country of nationality, the law of the country of nationality with which he/she has the closest connection shall be applied. If a natural person has no nationality, or if his/her nationality is unknown, the law of the place of his/her habitual residence shall be applied.Article 20 If the law of the place of habitual residence is to be applied according to the present Statute, and the place of habitual residence of a natural person is unknown, the law of the place ofhis/her current residence shall be applied.Chapter III Marriage and FamilyArticle 21 Conditions of marriage shall be governed by the law of the place of common habitual residence of the parties; they shall be governed by the law of the country of the common nationality in the absence of a place of common habitual residence; they shall be governed by the lex loci celebrationis if there exists no common nationality and the marriage is to be entered into at the place of habitual residence of one party or in his/her country of nationality.Article 22 Formalities of marriage are valid if they satisfy the lex loci celebrationis, the law of the place of habitual residence or the law of the country of nationality of one party.Article 23 Personal relationships of spouses shall be governed by the law of the place of their common habitual residence; in the absence of a place of common habitual residence, the law of the country of their common nationality shall be applied.Article 24 With regard to property relationships of spouses, the parties may choose by agreement the law of the place of habitual residence or the law of the country of nationality of one party, or the law of the place where the principal property is situated, as applicable. In the absence of a choice by the parties, the law of the place of their common habitual residence shall be applied; in the absence of a place of common habitual residence, the law of the country of their common nationality shall be applied.Article 25 Personal relationships and property relationships between parent and child shall be governed by the law of the place of their common habitual residence; in the absence of a place of common habitual residence, the law of the place of habitual residence or the law of the country of nationality of one party shall be applied, provided that it is the law favoring protection of the rights and interests of the weaker party.Article 26 With regard to divorce by agreement, the parties may choose by agreement the law of the place of habitual residence or the law of the country of nationality of one party as applicable. In the absence of a choice by the parties, the law of the place of their common habitual residence shall be applied; in the absence of a place of common habitual residence, the law of the country of their common nationality shall be applied; in the absence of a common nationality, the law of the place where the institution conducting the divorce formalities is situated shall be applied.Article 27 Divorce by litigation shall be governed by the lex fori.Article 28 Conditions and formalities of adoption shall be governed by the law of the place of habitual residence of the adopter and the law of the place of habitual residence of the adoptee. Effects of adoption shall be governed by the law of the place of habitual residence of the adopter at the time of adoption. Dissolution of an adoption relationship shall be governed by the law of the place of habitual residence of the adoptee at the time of adoption or the lex fori.Article 29 Maintenance shall be governed by the law of the place of habitual residence or the law of the country of nationality of one party, or the law of the place where the principal property is situated, provided that it is the law favoring protection of the rights and interests of the person to be maintained.Article 30 Guardianship shall be governed by the law of the place of habitual residence or the law of the country of nationality of one party, provided that it is the law favoring protection of the rights and interests of the ward.Chapter IV SuccessionArticle 31 Intestate succession shall be governed by the law of the place of habitual residence of the decedent upon his/her death, but intestate succession of immovable property shall be governed by the law of the place where the immovable property is situated.Article 32 A testament is valid as to form if the form of the testament satisfies the law of the place of habitual residence, the law of the country of nationality of the testator or the lex loci actus of the act of testament at the time of making the testament, or upon the death of the testator.Article 33 Effects of a testament shall be governed by the law of the place of habitual residence or the law of the country of nationality of the testator at the time of making the testament, or upon the death of the testator.Article 34 Matters such as the administration of estates shall be governed by the law of the place where the estates are situated.Article 35 Devolution of heirless estates shall be governed by the law of the place where the estates are situated upon the death of the decedent.Chapter V Rights in RemArticle 36 Rights in rem of immovable property shall be governed by the law of the place where the immovable property is situated.Article 37 The parties may choose by agreement the law applicable to rights in rem of movable property. In the absence of a choice by the parties, the law of the place where the movable property is situated at the time of the occurrence of the juristic fact concerned shall be applied.Article 38 The parties may choose by agreement the law applicable to any change of rights in rem of movable property that takes place during transport. In the absence of a choice by the parties, the law of the transport destination shall be applied.Article 39 Securities shall be governed by the law of the place where the rights of the securities are realized, or by any other law that has the closest connection with the securities.Article 40 Pledge of rights shall be governed by the law of the place where the pledge is established.Chapter VI ObligationsArticle 41 The parties may choose by agreement the law applicable to a contract. In the absence of a choice by the parties, the contract shall be governed by the law of the place of habitual residence ofone party whose performance of obligations can best embody the characteristics of the contract, or by any other law that has the closest connection with the contract.Article 42 Consumer contracts shall be governed by the law of the place of the consumer’s habitual residence; if the consumer has chosen the law of the place of the provision of commodities or services as applicable, or if the entrepreneur has not been engaged in relevant business activities at the place of the consumer’s habitual residence, the law of the place of the provision of commodities or services shall be applied.Article 43 Labor contracts shall be governed by the law of the place where the laborer works; if the place where laborer works is difficult to ascertain, the law of the principal place of business of the employing unit shall be applied. Labor dispatch may be governed by the law of the dispatching place.Article 44 Tortious liability shall be governed by the lex loci delicti, but it shall be governed by the law of the place of common habitual residence if the parties have a place of common habitual residence. If the parties agree to choose the applicable law after the occurrence of a tortious act, their agreement shall be followed.Article 45 Product liability shall be governed by the law of the place of habitual residence of the person whose right has been infringed upon; if the person whose right has been infringed upon has chosen the law of the principal place of business of the infringing person or the lex loci damni as applicable, or if the infringing person has not been engaged in relevant business activities at the place of habitual residence of the person whose right has been infringed upon, the law of the principal place of business of the infringing person or the lex loci damni shall be applied.Article 46 If rights of personality, such as right of name, right of portrait, right of reputation and right of privacy, have been infringed upon via the internet or by any other means, the law of the place of habitual residence of the person whose right has been infringed upon shall be applied.Article 47 Unjust enrichment or negotiorum gestio shall be governed by the law chosen as applicable by the parties by agreement. In the absence of a choice by the parties, the law of the place of common habitual residence of the parties shall be applied; in the absence of a place of common habitual residence, the law of the place of occurrence of the unjust enrichment or negotiorum gestio shall be applied.Chapter VII Intellectual Property RightsArticle 48 Devolution and contents of intellectual property rights shall be governed by the law of the place for which the protection is invoked.Article 49 The parties may choose by agreement the law applicable to the transfer and licensed use of intellectual property rights. In the absence of a choice by the parties, the provisions of the present Statute relating to contracts shall be applied.Article 50 Tortious liability arising out of infringement of intellectual property rights shall be governed by the law of the place for which the protection is invoked; after occurrence of the tortious act, the parties may also choose by agreement the lex fori as applicable.Chapter VIII Supplementary ProvisionsArticle 51 Where Articles 146 and 147 of the General Principles of Civil Law of the Peop le’sRepublic of China, and Article 36 of the Succession Law of the People’s Republic of China, differ from the provisions of the present Statute, the present Statute shall be applied.Article 52 The present Statute shall come into force on 1 April 2011.* Director of the Research Centre for Private International Law and Comparative Law, Tsinghua University School of Law, Beijing, China; Doctor of Laws, Wuhan University, China; LL.M. and doctor iuris, Universität des Saarlandes, Germany; professeur invite à la Faculté internationale de droit comparéde Strasbourg, France (since 2003); professeur invité à l’Université de Strasbourg, France (2005-2010); to teach a special course in French on La nouvelle codification du droit international privé chinois (The New Codification of Chinese Private International Law) from 30 July to 3 August 2012 at the Hague Academy of International Law during its 2012 summer session of private international law. Address: Tsinghua University School of Law, 100084 Beijing, China. E-mail: chenwz@. The present author owes great thanks to Kevin M. Moore (LL.M., Peking University; Legislative Aide, Oregon Senator Floyd Prozanski; juris doctor candidate, Willamette University College of Law) for his assistance and helpful suggestions.* * LL.M., Peking University; Legislative Aide, Oregon Senator Floyd Prozanski; juris doctor candidate, Willamette University College of Law.本文原载于《国际私法年刊》(Yearbook of Private International Law)第12卷(2010年),第669-674页,由德国sellier. european law publishers 和瑞士比较法研究所出版。

总第499期Vol.499大学(社会科学)University (Social Science )2021年2月Feb.2021名古屋议定书框架下遗传资源利用者的国内立法概述———欧盟规则与日本法的比较何劼(西南学院大学法学研究科,日本福冈8148511)摘要:名古屋议定书被认为是在遗传资源的相关权利保护方面最具有可实践性和实际拘束力的国际条约之一。

作为议定书缔约方中具有代表性的遗传资源利用者,欧盟和日本均批准加入了议定书,并且按照议定书第15条的要求采取了本国的司法性的、行政性的或者政策性的措施。

本文探索了名古屋议定书框架下遗传资源利用者的国内立法背景、主要制度、对不遵守规则者的应对,以及例外与限制。

研究发现,两个体系均设定有各种适用限制,这也对我国的相关立法在效率和时间上提出了一定的要求。

关键词:欧盟规则;应有的注意;ABS 指南;报告义务中图分类号:D93/97文献标识码:A文章编号:1673-7164(2021)05-0035-03作者简介:何劼(1986—),男,法学博士,日本西南学院大学法学研究科博士后研究员,研究方向:环境法、知识产权法、传统知识与遗传资源的保护。

①EU.Regulation (EU )No 511/2014of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16April 2014on Compliance Mea-sures for Users from the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization in the Union [DB/OL ].[2019-09-20].https ://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ :JOL_2014_150_R_0002.(该规则的英文文本可以在欧盟规则数据库EUR-Lex 中在线阅览)②mission Implementing Regulation (EU )2015/1866/of 13October 2015Laying Down Detailed Rules for the Implementation of Regulation (EU )No 511/2014of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards the Register of Collections ,Monitoring User Compliance and Best Practices [EB/OL ].[2019-09-20].https ://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/a0c57c2c-76f5-11e5-86db-01aa75ed71a1/language-en.(细则的英文文本可以在链接中获取)③这里的利用过程中的相关当事人包括资源的输入者、中转者、利用者(从事研究开发的个人或单位)、商业活动者(对资源及开发成果进行商业化利用,比如生产贩卖的个人或单位)以及排他性权利保有者。

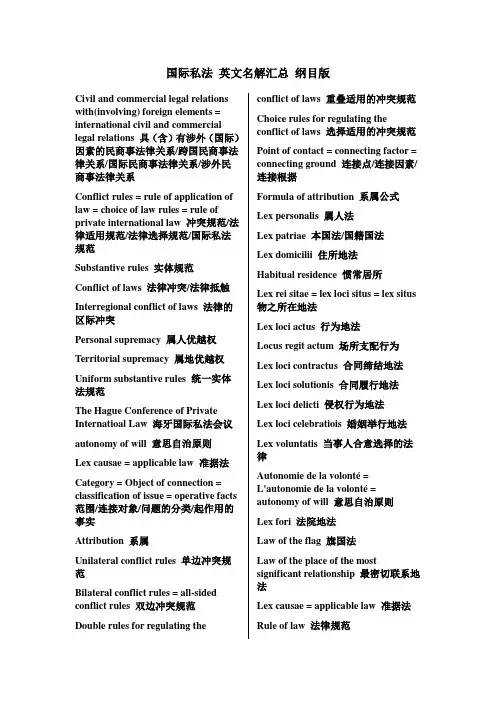

国际私法英文名解汇总纲目版Civil and commercial legal relations with(involving) foreign elements = international civil and commercial legal relations 具(含)有涉外(国际)因素的民商事法律关系/跨国民商事法律关系/国际民商事法律关系/涉外民商事法律关系Conflict rules = rule of application of law = choice of law rules = rule of private international law 冲突规范/法律适用规范/法律选择规范/国际私法规范Substantive rules 实体规范Conflict of laws 法律冲突/法律抵触Interregional conflict of laws 法律的区际冲突Personal supremacy 属人优越权Territorial supremacy 属地优越权Uniform substantive rules 统一实体法规范The Hague Conference of Private Internatioal Law 海牙国际私法会议autonomy of will 意思自治原则Lex causae = applicable law 准据法Category = Object of connection = classification of issue = operative facts 范围/连接对象/问题的分类/起作用的事实Attribution 系属Unilateral conflict rules 单边冲突规范Bilateral conflict rules = all-sided conflict rules 双边冲突规范Double rules for regulating the conflict of laws 重叠适用的冲突规范Choice rules for regulating the conflict of laws 选择适用的冲突规范Point of contact = connecting factor = connecting ground 连接点/连接因素/连接根据Formula of attribution 系属公式Lex personalis 属人法Lex patriae 本国法/国籍国法Lex domicilii 住所地法Habitual residence 惯常居所Lex rei sitae = lex loci situs = lex situs 物之所在地法Lex loci actus 行为地法Locus regit actum 场所支配行为Lex loci contractus 合同缔结地法Lex loci solutionis 合同履行地法Lex loci delicti 侵权行为地法Lex loci celebratiois 婚姻举行地法Lex voluntatis 当事人合意选择的法律Autonomie de la volonté =L'autonomie de la volonté = autonomy of will 意思自治原则Lex fori 法院地法Law of the flag 旗国法Law of the place of the most significant relationship 最密切联系地法Lex causae = applicable law 准据法Rule of law 法律规范Preliminary question = incidental problem 先决问题/附带问题Principal question 主要问题/本问题Jurisdiction-selecting rules 管辖权选择方法Substance 实体问题Procedure 程序问题Right 权利(问题)/实体问题Remedy 救济(问题)/程序问题Statues of limitation 时效问题Burden of proof 举证责任Presumptions 推定Presumptions of fact 事实的推定Presumptions of law 法律的推定Characterization = qualification = classification = identification 识别/定性/分类Movable property 动产Immovable property 不动产Personal property v. Real property Renvoi 反致Remission = renvoi au premier degré直接反致/一级反致/狭义反致Transmission = renvoi au second degré转致/二级反致Indirect remission 间接反致/大反致Double renvoi = foreign court theory 双重反致/外国法院说Evasion of law = fraude a la loi = fraudulent creation of points of contact 法律规避/法律欺诈/僭窃法律/欺诈设立连接点The reservation of public order 公共秩序保留制度Substantial contact 实质的联系The ascertainment of foreign law = proof of foreign law 外国法(内容)的查明/外国法的证明Nationality 国籍dependency 法定住所/从属住所Residence 居所Habitual resident 习惯居所/惯常居所Legal person 法人Public body 公共团体State immunity 国家豁免Immunity from jurisdiction = immunity ratione personae 司法管辖豁免/属人理由的豁免Immunity from execution/immunity ratione materiae 执行豁免/属物理由的豁免The doctrine of absolute immunity 绝对豁免理论The doctrine of relative or restrictive immunity 限制豁免论/职能豁免论Immunity of state property 国家财产豁免National treatment 国民待遇Most-favoured-nation treatment = MFN 最惠国待遇Preferential treatment 优惠待遇Non-discriminate treatment 非歧视待遇Capacity for right (民事)权利能力Allgemeine Rechtsfähigkeit 一般权利能力Besondere Rechtsfähigkeit 特别权利能力Declaration of absence 宣告失踪Declaration of death 宣告死亡/推定死亡Right in rem 物权Lex loci rei sitae = lex situs = Lex rei sitae物之所在地法Shares 股份Nationalization 国有化Requisition 征用Confiscation 没收Expropriation 征收Trusts 信托Trust property 信托财产Bills of exchange 汇票Promissory notes 本票Cheques 支票Intellectual property 知识产权/智慧产权Industrial property 工业产权Patent 专利Trade mark 商标Priority of registration “注册在先”原则Priority of use “使用在先”原则Copyright 著作权/版权Droit de autear 作者权理论Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property 《保护工业产权的巴黎公约》The doctrine of the most significant relationship 最密切联系原则The most real connection 最真实联系Contracting states 缔约国Reservation 保留Production sharing contract 产品分成合同The service contract 服务合同The law of the place of the tort 侵权行为地法The place of acting 加害行为实施地The place of injury 加害结果发生地The law of the forum 法院地法A mixture of the lex fori and the lex loci delicti = Rule of double actionability重叠适用侵权行为地法和法院地法/双重可诉原则Unjust enrichment 不当得利Negotiorum gestio = voluntary agency 无因管理Quasi-contractual obligation 准合同之债True successor 真正的继承人International civil procedure 国际民事诉讼International commercial arbitration 国际商事仲裁China International Ecomomic and Trade Arbitration Commission = CIETAC = The Court of Arbitration of China Chamber of International Commerce = CCOIC Court of Arbitration 中国国际经济贸易仲裁委员会/中国国际商会仲裁院Agreement of international commercial arbitration 国际商事仲裁协议Principal contract 主合同Arbitration clause 仲裁条款Submission agreement 仲裁协议书Litigation 排除诉讼Capacity (仲裁当事人的)资格The Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards 《承认和执行外国仲裁裁决公约》/《纽约公约》Exclusive jurisdiction 排他的管辖权Substantive law 实体法Adjective law 程序法Rules of procedure of arbitration 仲裁程序规则Mandatory rules 强制性规则Agency agreement 代理协定Home state 本国Direct line直接适用的法International jurisdiction = competence generale = competence internationale 国际管辖权/一般的管辖权Local jurisdiction = competence speciale = competence interne国内管辖权/特别的管辖权Competence generale directe 直接的一般管辖权Competence generale indirecte 间接的一般管辖权International judicial assistance in civil matters 国际(民事领域)司法协助Service = evidence abroad 司法协助Commissioner 特派员取证Public summons 公共传票Forcible service 强制送达Non-forcible service 非强制送达Nonformal service 非正式送达Arbitration 仲裁/公断Arbitrability 争议可仲裁性Arbitration clause 仲裁条款Submission to arbitration agreement 提交仲裁协议书Ad hoc arbitration agency 临时仲裁机构/特别仲裁机构/专设仲裁机构Institutional arbitration 机构仲裁Arbitration Court of International Chamber of Commerce = ICC国际商会仲裁院Arbitral proceedings 仲裁程序London Court of International Arbitration = LCIA 伦敦国际仲裁院Charted Institute of Arbitration 特许仲裁员协会China International Ecomomic and Trade Arbitration Commission = CIETAC 中国国际经济贸易仲裁委员会/中国国际商会仲裁院China Maritime Arbitration Commission = CMAC 中国海事仲裁委员会Final award 最后裁决Preliminary award 初裁决/预裁决Partial award 部分裁决Default award 缺席裁决No proper notice 未给予适当通知Unable to present the case 未能提出申辩。

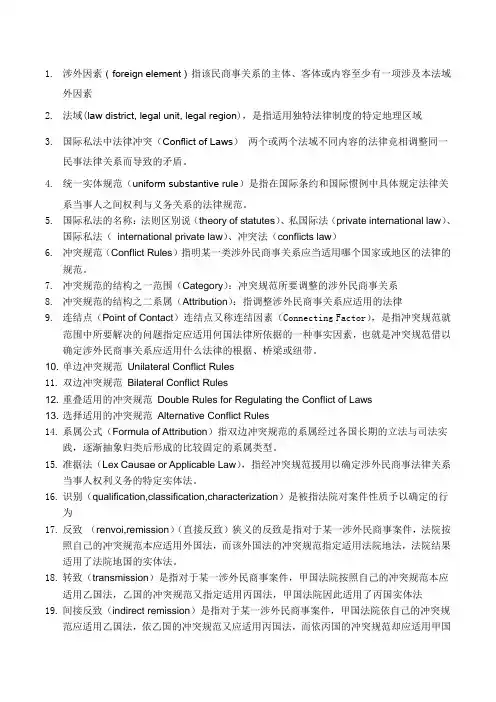

1.涉外因素(foreign element)指该民商事关系的主体、客体或内容至少有一项涉及本法域外因素2.法域(law district, legal unit, legal region),是指适用独特法律制度的特定地理区域3.国际私法中法律冲突(Conflict of Laws)两个或两个法域不同内容的法律竞相调整同一民事法律关系而导致的矛盾。

4.统一实体规范(uniform substantive rule)是指在国际条约和国际惯例中具体规定法律关系当事人之间权利与义务关系的法律规范。

5.国际私法的名称:法则区别说(theory of statutes)、私国际法(private international law)、国际私法(international private law)、冲突法(conflicts law)6.冲突规范(Conflict Rules)指明某一类涉外民商事关系应当适用哪个国家或地区的法律的规范。

7.冲突规范的结构之一范围(Category):冲突规范所要调整的涉外民商事关系8.冲突规范的结构之二系属(Attribution):指调整涉外民商事关系应适用的法律9.连结点(Point of Contact)连结点又称连结因素(Connecting Factor),是指冲突规范就范围中所要解决的问题指定应适用何国法律所依据的一种事实因素,也就是冲突规范借以确定涉外民商事关系应适用什么法律的根据、桥梁或纽带。

10.单边冲突规范Unilateral Conflict Rules11.双边冲突规范Bilateral Conflict Rules12.重叠适用的冲突规范Double Rules for Regulating the Conflict of Laws13.选择适用的冲突规范Alternative Conflict Rules14.系属公式(Formula of Attribution)指双边冲突规范的系属经过各国长期的立法与司法实践,逐渐抽象归类后形成的比较固定的系属类型。

证据法学英文Title: The Study of Evidence Law in the Field of Legal StudiesIntroduction:Evidence law plays a crucial role in the field of legal studies, providing the framework for determining the admissibility, relevance, and weight of evidence presented in a court of law. This article delves into the study of evidence law, exploring its fundamental principles, types of evidence, and the manner in which it influences the outcome of legal proceedings.I. The Basic Principles of Evidence LawA. Relevance:Relevance is a fundamental principle of evidence law, ensuring that the evidence presented in court is directly related to the issue at hand. Court proceedings require a connection between the evidence and the facts that need to be proven or disproven.B. Admissibility:Admissibility refers to the criteria that must be met in order for evidence to be considered legally valid. This includes rules on hearsay, authenticity, expert testimony, and the exclusion of illegally obtained evidence.C. Weight:Weight refers to the value or probative force of evidence. It is determined by the court based on its relevance, credibility, andpersuasiveness. The weight of evidence has a significant impact on the final determination of guilt or liability.II. Types of EvidenceA. Direct Evidence:Direct evidence is evidence that directly proves a fact at issue. It includes witness testimony, video footage, documents, or any tangible evidence that directly supports or contradicts the claims made by either party.B. Circumstantial Evidence:Circumstantial evidence indirectly proves a fact, relying on inferences drawn from a combination of circumstances. It consists of facts that, when taken together, imply the existence of the fact in question.C. Documentary Evidence:Documentary evidence refers to written or printed documents that are formally admitted by the court as evidence. This includes contracts, letters, emails, medical records, and other forms of written communication that are relevant to the case.D. Expert Testimony:Expert testimony is presented by qualified individuals with specialized knowledge or skills in a specific field. Their testimony provides insight, explanations, and opinions that assist the court in understanding complex issues and making informed decisions.III. The Role of Evidence in Legal ProceedingsA. Burden of Proof:Evidence plays a pivotal role in establishing the burden of proof, which is the responsibility of the party making the claim. Depending on the legal system, the burden of proof may be placed on the prosecution (in criminal cases) or the plaintiff (in civil cases).B. Presumption of Innocence:The principle of the presumption of innocence places the burden of proof on the prosecution in criminal cases. It requires the prosecution to present sufficient evidence to convince the court of the defendant's guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.C. Standard of Proof:The standard of proof is the level of certainty required to establish the truth or falsehood of a disputed fact. It differs in different legal systems, with criminal cases generally requiring proof beyond a reasonable doubt and civil cases relying on the balance of probabilities.IV. The Influence of Evidence Law on Legal Decision-MakingA. Judicial Discretion:Judicial discretion allows judges to evaluate and determine the weight and admissibility of evidence presented in court. It grants judges the authority to make informed decisions based on their expertise, legal principles, and the specific circumstances of each case.B. Precedents:Decisions made in previous cases, known as precedents, have a significant impact on the interpretation and application of evidence law. Judges often refer to these precedents to maintain consistency and predictability in the legal system.C. Appeal Process:The credibility and sufficiency of evidence can be challenged during the appeal process, providing an avenue for reconsideration if there are doubts about the fairness or accuracy of the original decision.Conclusion:The study of evidence law is of utmost importance in the field of legal studies. It forms the backbone of legal proceedings by ensuring the admissibility, relevance, and weight of evidence presented in court. Understanding the principles and types of evidence, as well as their role in legal decision-making, is essential for legal practitioners, scholars, and anyone interested in the field of law.。

2021年2月Feb. 2021《齐齐哈#$学学&》('学社会科学版).Journal of Qiqihar University^ Phi& Soc Sci )形式法治的关怀、理据和图景曾星星,胡平仁(中南大学法学院,湖南长沙410012 )摘要:西方形式法治观是一种以权力制约和自然权利保障为现实关怀的理论学说,但其现实指向却是以自然权利确认、保障和实现为目标的社会实践。

以自然权利为理据的形式法治观,在市场经济背景条件下却抽空了 主权者(国家)的意志,取而代之的是返还于“自然状态”中的个体意志。

在市场经济体制下,所有个体意志逆向转化为自由市场中的资本要素,由此,形式法治观最终导向的是绝大多数个体意志洽丧为资本的附庸。

关键词:形式法治;自然权利;市场经济;法治图景中图分类号:D920.0 文献标识码:A 文章编号:1008-2638( 2021 )02-0079-04The Care , Rationale and Vision of the Formal Rule of LawZENG Xing-xing , HU Ping-ren(Law School of Central South University, Changsha Hunan 410000, China )Abstract :The western form of the rule of law is a theoretical doctrine that takes power restriction and the protection of naturalrights as practical concerns , but its practical orientation is social practice with the goal of confimiing , guaranteeing and realizing natural rights. The fomial concept of rule of law based on natural rights has emptied the sovereign's ( state ) will in the context of a market e cono y and replaced it ith the individual ill returned to the “ state of nature ” . nder the arket econo y syste , all individual illsare reversely transfor ed into capital ele ents in the free arket. s a result , the concept of for al rule of la ulti ately leads to theovervhelming majority of individual wills becoming vassals of capital.: for al rule of la ; natural rights ; arket econo y ; picture of rule of la法治作为一种特定政治法律理想已经获得普遍共识,法 治的话语也已然逐步取代传统道德、政治话语成为当下中国话语体系中新的真理建制。

高三英语文章公平正义单选题50题1.Fairness, justice and equality are important concepts. In a just society, people are treated equally and have access to the same opportunities. What is the main difference between fairness and justice?A.Fairness emphasizes equal treatment, while justice emphasizes moral rightness.B.Fairness emphasizes moral rightness, while justice emphasizes equal treatment.C.Fairness and justice have no difference.D.Fairness is only for the rich, while justice is only for the poor.答案:A。

公平(fairness)强调平等对待,而正义(justice)强调道德上的正确性。

2.In history, many people fought for justice. Which of the following is most closely related to justice?A.WealthB.PowerwD.Fame答案:C。

在历史上,许多人都为正义而战。

法律(Law)与正义最为密切相关,因为法律旨在维护公平正义。

3.What does equality mean in the context of fairness and justice?A.Everyone has the same amount of money.B.Everyone has the same opportunities and rights.C.Everyone has the same job.D.Everyone has the same hobbies.答案:B。

“北大法宝”中文在线数据库vip.c hinalaw info.c om一、北大法律信息网简介建站时间:1995年特点:国内成立时间最早、规模最大的法律综合站点;内容:以“北大法宝”在线数据库为主要内容,辅以天问咨询、法律网校、法学文献、法律网站导航等众多法律信息服务北大法律信息网是由北大法学院创建和主管的全国最早的法律网站,现由北大英华公司运营、北大法制信息中心协办,以法律信息、法律教育、法律技术为主营业务。

其主要产品和服务为:北大法宝-《中国法律检索系统》,北京大学法学远程教育,英华司法考试培训。

这些产品和服务已在行业内取得了领先优势。

北大法宝目前已成为全国市场占有率最高的法律信息服务产品,拥有众多的法律机构用户。

2004年10月“北大法宝”为基础,为人民法院系统研制的《中国审判法律应用支持系统》荣获了国家电子出版物奖,并已在全国大多数法院投入使用。

二、“北大法宝”中文在线数据库内容“北大法宝”在线收录了1949年至今24万多篇法律文件(数据不断更新中),详细分为15个子数据库,涵盖了法律和法学文献资源的各个方面,是目前收录内容最全面的法律专业数据库之一,并且推出了免费“最新立法简介”邮件订阅服务,可以随时了解立法动态。

并且进一步的内容扩充和新产品计划包括:收录更多法学期刊的内容,丰富法学论文库。

三、“北大法宝”的资料来源在规范性文件收录方面,尽量采用《中华人民共和国立法法》及有关规定认可的政府出版物(公报、政报)所登载的法规文本,同时获得全国人大常委会、国务院法制办、最高人民法院等机关大力支持,保证法规收录渠道具有权威性。

在数据信息化处理过程中参照正式出版物的质量要求进行录入、校对和编辑,力求数据准确,保持法规文本的严肃性和检索结果的准确性。

四、“北大法宝”功能(详见《用户指南》)“北大法宝”除包括跨库检索,复合检索以及二次检索等功能外,还可以实现下载,打印,转发,浏览字体大小调整等多种功能。

·贵州■官职韭学院学报·JO U R从【O f G UI Z HO U r OU C EO F F lC E RV O C盯I O_从C O L【瞄E检察机关非法取证行为调查核实权的正当程序完善以《刑事新讼法》和《人民检嚓蝴l事新喻溯则(铀瀚)》为视墒口张少波,刘青(东莞市第三市区人民检察院,广东东莞523710)摘要:检察机关对非法取证行为是否享有调查核实权一直是理论和实践中争i'e-的热点问题修改后的《中华人民共和国丹q事诉讼法》对检察机关该项权力的确立,契合了检察机关的职能定位和司法实践的现实需要。

但鉴于法律条文对简洁性和凝练性的内在要求,该规定难免失之原则与抽象?尽管修改后的《人民检察院刑事诉讼规则(试行)》细化了上述规定,但仍未能涵盖司法实践中可能遭遇的各种困境应通过保障权力行使线索来源、科学界定两类不同权{力行使对象以及健全权力行使法律效果等正当程序对检察机关的调查核实权予以完善二关键词:非法取证;调查核实权;检察机关非法取证行为调查核实权Perfect ing t h e P rocu rator ate,s R i gh t o f Investigating an d C h e ck i n g I ll eg al ly Ob ta i ni ng E vi de n ce B eh av i or by DueP ro c e du r e——_T啦ng th e N e w l y—a me n d e d C rim in al Procedure Law and t h e Pe o p l e"s Procuratorate Criminal Rules(Trial)aS A ng leZHA NG S h a o—b o,L I U Qing(No.3 Municipal P eopl e,S Pro cur ato rat e,S of D on g gu a n Ci ty,I)on g gu a n 523710,Guan gdong Provillee,P.R.China) Abstract:Whether the p r oc u ra t or a te h a s the r ight of in ve sti ga ti ng and check ing of ill ega ll y'o bta in ing evidence is t he h ot top ic i n th e or y an d pr a ct i ce.T h e Amendments to the Cr inf in al I且w of th e PRC(the8th Edition)confirmed th e procuratorate,S right,wh i ch meets the realistic requirements of prtm urato rale,S f un ct io na l po si tio n all{{iudicialy p ra c ti ce.B ut in c on s id e ra t io n of t he inl ern al 1.e quir emen ts of si mp li ci ty a nd cohesion of l egal art icles,th e re g ul a rion i s hm’d tO av oi d pr in ci p le and ab s t ra c ti o n.T h e a m e n de d People,S Pro eur ato rate,s C ri nfi na I Pr ocedur e Regulation(Trial)detailed th e a bove—mention ed re gu la ti on,bu t il di d n,l t he dif fi cu hi es that w e may meet in judiciary pi’a cf i c e.S o th e procul‘atorate.s l‘i g h t of in ve st ig at in g an d chec king s h o u l d be p P fl e e te d by pr ot ec ti ng th e power use,s(‘i e n t i f i c a ll y d ef i ni ng t he two kin d s of subjects of power use,es ta bl is hi ng the e ff ect iv en es s ot、po wer u,q e and o th er due processes.Key Words:illegally obtaining e v i d en c e;r i g ht of i nv e st i ga t in g and checking;the procuratorate.S right of in ve s ti g at i ng and checking illegally o bt a i ni n g evidence[中图分类号:D925.2 文献标识码:A 文章编号:1671—5195(2013)02—0045—05】为规范侦查机关的取证行为,遏制司法实践中动,促进惩罚犯罪与保障人权相平衡,修改后的存在的刑讯逼供,暴力、威胁取证等非法取证活《中华人民共和国刑事诉讼法》(以下简称修改后收稿日期:2012—12-06 基金项目:广东省东莞市社会科学联合会科研项目(2012ZDB02)。