Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Management of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:352.01 KB

- 文档页数:10

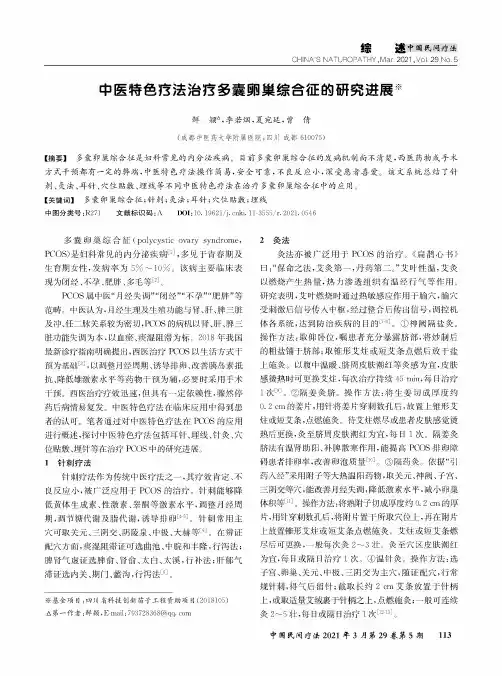

9:CHINA'S NATUROPATHY,Mar.2021,Vol.29No.5中医特色疗法治疗多囊卵巢综合征的研究进展※鲜颖,李若烟,夏宛廷,曾倩(成都中医药大学附属医院,'川成都610075)【摘要】多囊卵巢综合征是妇科常见的内分泌疾病。

目前多囊卵巢综合征的发病机制尚不清楚,西医药物或手术方式干预都有一定的弊端,中医特色疗法操作简易,安全可靠,不良反应小,深受患者喜爱。

该文系统总结了针刺、灸法、耳针、穴位贴敷、埋线等不同中医特色疗法在治疗多囊卵巢综合征中的应用目【关键词】多囊卵巢综合征;针刺;灸法;耳针;穴位贴敷;埋线中图分类号:R270文献标识码:A DOI:10.19621/ki.11-3555/r.2021.0546多囊卵巢综合征(polycystic ovary syndrome, PCOS)是妇科常见的内分泌疾病多见于青春期及生育期女性,发病率为5%〜10%。

该病主要临床表现为闭经、不孕、肥胖、多毛等闪1PCSS属中医“月经失调”“闭经”“不孕”“肥胖”等范畴。

中医认为,月经生理及生殖功能与肾多干、脾三脏及冲、任二脉关系较为密切,PCOS的病机以肾多干、脾三脏功能失调为本,以血瘀、痰湿阻滞为标该20%年我国 最新诊疗指南明确提出,西医治疗PCOS以生活方式干预为基础闪,以调整月经周期、诱导排卵、改善胰岛素抵抗、降低雄激素水平等药物干预为辅,必要时采用手术干预。

西医治疗疗效迅速,但具有一定依赖性,骤然停药后病发。

中医特色疗法在临床应用中得到患者的认可。

笔者通过对中医特色疗法在PCOS的应用 进行概述,探讨中医特色疗法包括、埋线、针灸、穴位贴敷、埋针等在治疗PCOS中的研究进展。

1针刺疗法针刺疗法作为传统中医疗法之一,其疗效肯定、不良反应小,被广泛应用于PCOS的治疗。

针刺能够降低黄体生成素、性激素、睾酮等激素水平,调整周期,调节糖代谢及脂代谢,诱导排卵匚6该针刺常用主穴可取关元、三阴交、阴陵泉任极、大赫等6在辨证方面,痰湿阻滞证可选、中脱和丰隆,行泻法;脾肾气虚证选脾俞、肾俞、太白、太溪,行补法;肝郁气滞证选内关、期门、蠡沟,行泻法囚。

![2021医学考研复试:老年病1[SC长难句翻译文]](https://uimg.taocdn.com/edcf49556bd97f192379e911.webp)

SCI长难句老年病学第一章-姑息医学Cancer is primarily a disease of the elderly and the palliation of both disease-and treatment-related symptoms is of importance in the practice of cancer medicine in all patients.Many older patients are treated within community hospitals,in which anticancer therapies are less likely to be given and in which the palliation of symptoms should be of primary importance.Many oncologists struggle with the palliation of symptoms in patients who are near the end of life.This is despite the considerable energies that are spent in palliating symptoms in patients who are receiving anticancer therapies at all disease stages.癌症主要是老年人的疾病,缓解与疾病和治疗相关的症状对所有患者的癌症医疗实践都非常重要。

许多老年患者在社区医院接受治疗,那里进行抗癌治疗的可能性很小,减轻症状应是最重要的。

许多肿瘤学家都在为缓解晚期病人的症状而努力。

尽管在所有疾病阶段接受抗癌治疗的患者在减轻症状方面都花费了相当大的精力。

知识点总结:①palliation n.减轻②oncologist n.肿瘤学家SCI长难句老年病学第二章-老年综合征Frailty is a new and emerging syndrome in the field of geriatrics.The study of frailty may provide an explanation for the downward spiral of many elderly patients after an acute illness and hospitalization.The fact that frailty is not present in all elderly persons suggests that it is associated with aging but not an inevitable process of aging and may be prevented or treated.The purpose of this article is to review what is known about frailty,including the definition,epidemiology,and pathophysiology,and to examine potential areas of future research.衰弱是老年医学领域中新出现的一种综合征。

二型糖尿病文献综述范文英文回答:Type 2 Diabetes: A Comprehensive Literature Review.Abstract.Type 2 diabetes is a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia and insulin resistance. It is a major public health concern, affecting millions of people worldwide. This literature review provides an overview of type 2 diabetes, including its epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management. The review also discusses current research and emerging therapies for type 2 diabetes.Epidemiology.The prevalence of type 2 diabetes has increased dramatically over the past few decades. It is estimatedthat over 462 million people worldwide have type 2 diabetes, and this number is expected to rise to 700 million by 2045. Type 2 diabetes is more common in certain populations, such as individuals who are overweight or obese, have a family history of the disease, or are of certain ethnicities.Pathophysiology.Type 2 diabetes is primarily caused by insulin resistance. Insulin is a hormone produced by the pancreas that helps glucose enter cells. In type 2 diabetes, thebody becomes resistant to the effects of insulin, resulting in hyperglycemia. Over time, the pancreas may also lose its ability to produce enough insulin, further exacerbating the hyperglycemia.Clinical Presentation.The clinical presentation of type 2 diabetes varies widely. Some individuals may experience classic symptoms such as polyuria, polydipsia, and unexplained weight loss. Others may have no symptoms at all. Over time, uncontrolledtype 2 diabetes can lead to serious complications,including cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, and diabetic retinopathy.Diagnosis.The diagnosis of type 2 diabetes is based on blood glucose levels. A fasting blood glucose level of 126 mg/dL or higher on two separate occasions is diagnostic for type 2 diabetes. An oral glucose tolerance test may also be used to diagnose type 2 diabetes.Management.The management of type 2 diabetes involves lifestyle modifications and medication. Lifestyle modifications include weight loss, regular exercise, and a healthy diet. Medications for type 2 diabetes include oral medications such as metformin and sulfonylureas, and injectable medications such as insulin.Current Research and Emerging Therapies.Current research on type 2 diabetes focuses on developing new medications and therapies to improveglycemic control and prevent complications. Some promising emerging therapies include incretin-based therapies,sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists.Conclusion.Type 2 diabetes is a major public health concern that affects millions of people worldwide. Understanding the epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of type 2 diabetes is crucial for healthcare professionals and patients alike. Ongoing research and the development of new therapies are essential for improving the lives of individuals with type 2 diabetes.中文回答:2型糖尿病,综合文献综述。

《牛津临床医学手册(第十版)英文原版》The Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine, Tenth Edition, is a comprehensive and authoritative guide to the latest advancements in clinical medicine. Renowned for its concise yet comprehensive coverage, this handbook provides a one-stop reference for busy clinicians seeking to stay up-to-date with the latest evidence-based practices.The handbook begins with a section dedicated to basic sciences, providing a solid foundation for understandingthe underlying mechanisms of disease. This section covers topics such as anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, immunology, and pharmacology, ensuring that clinicians have a solid grasp of the fundamental principles of medicine.The subsequent chapters delve into the specificdiseases and disorders, organized by systems of the body. Each chapter provides a detailed overview of the epidemiology, etiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of the respective disease. The handbook also includes up-to-date information on new drugs, therapies, and treatment modalities, ensuringthat clinicians are equipped with the latest tools and knowledge to deliver optimal patient care.Another noteworthy feature of this handbook is its emphasis on evidence-based medicine. The authors have carefully selected and referenced the latest research and clinical trials, ensuring that the information provided is based on solid evidence. This approach not only helps clinicians make informed decisions but also encourages a culture of continuous learning and improvement in medical practice.The Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine, Tenth Edition, is not just a book; it's a trusted companion for clinicians on their journey of lifelong learning. Its portability and user-friendly format make it an ideal reference for busy clinicians who need quick access to reliable information. Whether you're a student, a resident, or a practicing clinician, this handbook will serve as your reliable guideto the world of clinical medicine.**《牛津临床医学手册(第十版)英文原版》深度剖析** 《牛津临床医学手册(第十版)英文原版》是临床医学领域最新进展的全面而权威的指南。

《2021年日本胃肠病学会循证临床实践指南:胆石症》意见要点陈祯美,林晶,陈进宏复旦大学附属华山医院普外科肝胆外科中心,上海 200040通信作者:陈进宏,*********************(ORCID: 0000-0003-0952-9990)摘要:2010年日本胃肠病学会(JSGE)首次发布以循证医学为基础的胆石症临床实践指南,并于2016年进行更新。

2023年4月,基于1983年—2019年8月Medline、Cochrane以及Igaku Chuo Zasshi等数据库中关于胆石症相关临床问题及近5年最新文献证据,JSGE发布胆石症循证临床实践指南(2021)。

本次修订分别从流行病学、发病机制、诊断、治疗、预后及并发症等方面,对上一版中的临床问题进行回顾并重新划分为三类共52个问题:29个背景问题涉及基础背景知识、19个临床问题和4个需进一步积累证据的未来研究问题,为胆石症患者的临床管理决策提供指导。

关键词:胆石症;诊断;治疗学;日本;诊疗准则A brief introduction of Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for cholelithiasis 2021 by the Japanese Society of GastroenterologyCHEN Zhenmei,LIN Jing,CHEN Jinhong.(Center of Hepatobiliary Surgery,Department of General Surgery,Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200040, China)Corresponding author: CHEN Jinhong,*********************(ORCID: 0000-0003-0952-9990)Abstract:The Japanese Society of Gastroenterology (JSGE)first published evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for cholelithiasis in 2010, followed by a revision in 2016. In April 2023, JSGE published the 2021 edition of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for cholelithiasis based on the clinical issues associated with cholelithiasis in the databases such as Medline,Cochrane, and Igaku Chuo Zasshi and the latest evidence in literature published in the past five years. The revised edition reviews related clinical questions in the previous edition from the aspects of the epidemiology,pathogenesis,diagnosis,treatment,prognosis, and complications of cholelithiasis and reclassifies them into three categories, with 52 questions in total, among which there are 29 background questions dealing with basic background knowledge,19 clinical questions,and 4 future research questions requiring further accumulation of evidence, thereby providing guidance for decision making in the clinical management of patients with cholelithiasis.Key words:Cholelithiasis; Diagnosis; Therapeutics; Japan; Practice Guideline1 流行病学与发病机制背景问题1.1 胆石症发病率(1)近年来,胆石症的发病率随肥胖人口的增加而增加,因此肥胖是胆石症危险因素。

地中海贫血书籍1. 《地中海贫血:基因、分子与临床》(Mediterranean Anemia: Genes, Molecules, and Clinics)-编者:Antonino Caruso等人。

这本书提供了关于地中海贫血基因、分子和临床方面的最新研究和进展。

2. 《地中海贫血:分子病理学和治疗方法》(Mediterranean Anemia: Molecular Pathology and Therapeutic Strategies)-编者:George Stamatoyannopoulos等人。

该书综述了地中海贫血的分子病理学,以及目前用于治疗该疾病的策略。

3. 《地中海贫血:临床与实验室方面的综述》(Mediterranean Anemia: Clinical and Laboratory Aspects)-编者:Hassan M. Yaish等人。

这本书提供了地中海贫血的临床特征和实验室诊断方面的详细综述。

4. 《地中海贫血:病理生理学和治疗进展》(Mediterranean Anemia: Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Advances)-编者:Guilhem Bousquet等人。

该书深入探讨了地中海贫血的病理生理学机制,并介绍了最新的治疗进展。

5. 《地中海贫血:遗传学、生物学和治疗方法》(Mediterranean Anemia: Genetics, Biology, and Therapeutics)-编者:Giovanni Caocci 等人。

该书综合了地中海贫血的遗传学、生物学和治疗方法的知识。

6. 《地中海贫血:临床管理指南》(Mediterranean Anemia: Clinical Management Guidelines)-作者:Panos Ioannou等人。

这本书提供了地中海贫血的临床管理和治疗指南,以帮助医生和患者更好地应对这一疾病。

文献生词malignancy 恶性,恶性肿瘤hepatectomy 肝切除术bilirubin 胆红素bilirubinemia 胆红素血症Hyperbilirubinemia 高胆红素血症Indocyanine green 吲哚花青绿indocyanine green retention 靛青绿滞留量试验hepatic insufficiency 肝功能不全,肝功能衰退jaundice 黄疸retrospective review 回顾性调查intraoperative 手术中的,术中parameters 参数Logistic Regression Logistic回归prognosis 预后prognostic 预后的hilar 门的,脐的cholangiocarcinoma 胆管上皮癌intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma 肝内胆管癌anatomic 解剖的,解剖学的hepatic hilus 肝门perioperative 围手术期的indication 适应证,指征curative 治愈的resection 切除术likelihood 可能性liver function 肝功能metastasis 转移hepatocellular carcinoma 肝细胞癌unexpected 意外的,忽然的cholestasis 胆汁淤积biliary drainage 胆汁引流extended hemihepatectomy 扩大半肝切除术Trisegmentectomy 三段切除Chronic viral hepatitis 慢性病毒性肝炎cirrhosis 肝硬化serum 免疫血清,血清on admission 入院时,住医院时percutaneous 经皮的transhepatic 经肝的endoscopic biliary drainage 内镜胆管引流,内镜胆管引流术, endoscopic 内窥镜的;内窥镜检查的drainage tube 引流管,排液管portal vein 门(静)脉embolization 栓塞,栓塞术,栓子形成peritoneal 腹膜的dissemination 播散,散布laparotomy 剖腹手术distant metastasis 远端转移Surgical Procedures 外科手术anastomosis 吻合术enteric 肠的in terms of 以…的观点;以…的方式hemorrhage 出血hemorrhagic 出血性的hemolysis 溶血hemolytic 溶血的hematology 血液学hematological 血液的hemodynamics 血流动力学coagulation status 高凝状态prothrombin time 凝血酶原时间activated partial thromboplastin time 激活部分促凝血酶原激酶时间antithrombin 抗凝血酶thrombolytic 溶血栓药,血栓溶解剂duration 持续时间;期间nonlinear least squares method 非线性最小平方法natural logarithm 自然对数categorize 分类galactose tolerance test 半乳糖耐量试验half life 半衰期computed tomography scan 计算机体层摄影扫描,CT扫描contrast medium 对比剂,造影剂bolus 推注integrated software 集成软件variables 变量continuous variable 连续变量categorical variable 分类变量univariate 单变量multivariate 多变量univariate analysis 单变量分析multivariate analysis 多元分析,多元统计分析stepwise procedure 逐步过程chi square test χ2检验,卡方检验,cutoff value 截断值Odds Ratio 比值比Mann Whitney test 曼-怀二氏检验tailed 有…尾的receiver operating characteristic curve 接受者(机)操作特征曲线morbidity and mortality 并发症和死亡率decompression 减压in regard to 关于,至于living related liver transplantation 活体亲属供肝肝移植术parenchyma 实质liver parenchyma 肝实质excretory 排泄的,分泌的parenchymal 质的,主质的shrinkage 皱缩,皱缩度biotransformation 生物转化adenosine triphosphate 三磷腺苷ammonia 氨Aspartate Aminotransferase 天冬氨酸氨基转移酶Alanine Aminotransferase 丙氨酸氨基转移酶Lactate Dehydrogenase 乳酸脱氢酶alkaline phosphatase 碱性磷酸酶glutamyl 谷氨酰基Inferior Vena Cava 下腔静脉abdominal aorta 腹主动脉Paraaortic 主动脉旁的celiac axis 腹腔干common hepatic artery 肝总动脉proper hepatic artery 肝固有动脉superior mesenteric Artery 肠系膜上动脉Hepatic artery thrombosis 肝动脉血栓形成pseudoaneurysm 假性动脉瘤portacaval shunt 门(静脉与)腔静脉分流术arterialization 动脉化angiography 血管造影术occlusion 闭塞梗塞occluded 闭塞的collateral 侧的,侧支,副的confluence 合流,汇流autologous vein graft 自体静脉移植物porta hepatis 肝门Portal lymph node 肝门淋巴结second order biliary radicles 二级胆管根lobar atrophy 肝叶萎缩caudate lobe 尾状叶falciform ligament 肝镰状韧带periampullary 壶腹周围的Retroduodenal 十二指肠后的jejunum (jejunal) 空肠(的)ileum (ileal) 回肠(的)colon(colonic) 结肠(的)rectum (rectal) 直肠(的)anal canal 肛管oncology 肿瘤学oncological 肿瘤学的neoplasm 肿瘤,新生物neoplastic 肿瘤的,新生物的neoplastic seeding 肿瘤播种papillary tumor 乳头瘤adenocarcinoma 腺癌cystadenoma 囊腺瘤testis 睾丸gastrinoma 胃泌素瘤squamous cell carcinoma 鳞状细胞癌carcinoid tumors 类癌sarcoma 肉瘤focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) 局灶性结节性增生parenchymal disease 器质性疾病advanced cancer 晚期癌症well differentiated 分化良好nodule 结节nodal metastases 淋巴结转移therapeutic effect 疗效neoadjuvant chemotherapy 新辅助化疗radiofrequency ablation 射频消蚀arterial chemoembolization 动脉化疗性栓塞infiltrating 浸润macroscopically 肉眼[检查]的;目视的carcinoembryonic antigen 癌胚抗原indication 适应症指征contraindication 禁忌证preoperative workup 术前全面评估postoperative morbidity rate 术后并发症发生率operative approach 手术入路radical operation 根治术,根治性手术en bloc 整个地,整块地inoperable 不能手术的,不能做手术的palliative 姑息的diagnostic laparoscopy 诊断性腹腔镜检查non-therapeutic laparotomy 非治疗性剖腹探查术invasive techniques 微创技术procedural complications 手术并发症pancreaticoduodenectomy 胰十二指肠切除术Adrenalectomy 肾上腺切除术thrombectomy 血栓摘除术lymphadenectomy 淋巴结切除术Lymph Node Dissection 淋巴结清扫术lymph node harvest 淋巴结清扫end to side anastomosis 端侧吻合术hepaticojejunostomy 肝空肠吻合术cholecystectomy 胆囊切除术Caudate lobectomy 尾状叶切除术radiopharmaceutical agent 放射性药剂iodized oil 碘化油absolute ethanol 无水乙醇scintigraphy 闪烁扫描术helical 螺旋的,螺旋状,螺旋状的cross sectional imaging 横断层面成像magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 磁共振成像endoscopy retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)内镜下逆行胆胰管造影magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)磁共振胰胆管成像intraoperative ultrasonography 术中超声检查法contrast enhanced computed tomography对比增强扫描CTpositron emission tomography PET正电子发射断层扫描cholangiogram 胆管造影Recurrence 复发follow up 随访concomitant 伴发的,附随的comorbidities 并存病bleeding 出血,流血extravasation 外渗,溢出hemobilia 胆道出血biliary fistula 胆瘘pleural effusion 胸腔积液lung edema 肺水肿splenomegaly 脾肿大hypersplenism 脾功能亢进hepatic encephalopathy 肝性脑病ascites 腹水subphrenic abscess 膈下脓肿endotoxaemia 内毒素血症myocardial infarction 心肌梗死pyrexial 发热的hypothermic 低体温的Biliary Stricture 胆管狭窄steatohepatitis 脂肪性肝炎fatty liver 脂肪肝adipose tissue 脂肪组织primary sclerosing cholangitis 原发性硬化性胆管炎angina 心绞痛sepsis 败血症,脓毒症perfusion 灌注ex vivo 离体,在活体外in situ 原位right upper quadrant 右上象限proximal part 近心端perineural 神经周围的bifurcation 二根分叉部,分岔ipsilateral 身体的同侧的,同侧的Institutional Review Board 机构审查委员会Ethics Committees 伦理学委员会predispose to 易患,使易感染、诱发platelet 血小板hyperalimentation 高营养支持cirrhotic 硬变的morbidity 并发症,发病率medications 用药dislodge 移去,逐出,取出gonadal 性腺的,生殖腺的Histologic 组织学的frozen section 冰冻切片atrophy 萎缩hypertrophy 肥大,过度生长proliferation 增生,增殖hyperplasia 增生;数量性肥大Stem cells 干细胞bone marrow derived 骨髓衍生的epithelium 上皮,上皮细胞encased 包裹reconstruction 重建,再造,重构inflammatory 炎症性的broad spectrum antibiotics 广谱抗菌素blood culture 血培养Gram Negative bacillus 革兰阴性[芽胞]杆菌cut surface 切面stent 支架catheter 导管direct cannulation 直接插管spectrophotometer 分光光度计rupture 破裂,vt.(使)破裂somatostatin 生长抑素Extracellular Matrix 细胞外基质cohort 同期组群Length of Stay 住院时间after discharge 出院后stratified 分层的,成层的clear cut 明确的In this regard 在这方面come at a cost 是有代价的progressively 进行性地,渐进地rationale 原理,基础理论homogeneous 同类的同质的heterogeneous 异类的,不同的putative 假定的omnipotent 全能的,无所不能的as controls 作为对照preconditioned 预处理preconditioning 预处理prospectively 前瞻性prospective randomized date 前瞻性随机数据Disease-Specific survival 疾病特异性生存率irreversible 不可逆的references 参考Cochrane 循证医学cholangiopancreatography 胰胆管造影术resolution 分辨率(决心,决议解决)herein 如此,鉴于,在此处iatrogenic 医源性palliation 缓和,减轻running suture 连续缝合orthotopic liver transplantation 原位肝移植chemoradiation 放化疗preneoplastic change 癌前变化carcinogenesis 致癌作用dysplasia 发育不良,不典型增生endoprosthesis 内镜置管术pruritus 瘙痒pruritis 瘙痒症Etiology (aetiology) 病原学etiologic 病原学的epidemiology 流行病学epidemiological 流行病学的pathophysiology 病理生理学lesion 病变Radionuclide 放射性核素nitrosamine 亚硝胺类pathogenesis 发病机制carcinoid 类癌Mucinous Adenocarcinoma 粘液腺癌Clear cell adenocarcinoma 透明细胞腺癌Signet ring cell adenocarcinoma 印戒细胞腺癌Adenosquamous Carcinoma 腺鳞状癌Squamous Cell Carcinoma 鳞状细胞癌Oat Cell Carcinoma 燕麦细胞癌Undifferentiated Carcinoma 未分化癌Papillomatosis 乳头状瘤病Papillary Carcinoma 乳头状癌hepatoblastoma 肝母细胞瘤Haemangioendothelioma 血管内皮瘤neuroendocrine tumour 神经内分泌瘤Leiomyosarcoma 平滑肌肉瘤malignant fibrous histiocytoma 恶化纤维组织细胞瘤nodular tumors 结节性肿瘤cachexia 恶液质sterilize 灭菌,消毒surgical radicality 手术的根治性angiogenetic 血管生成angiogenic 血管源性的,生成血管的antiangiogenic 抗血管生成的chemosensitization 化疗增敏photosensitizer 感光剂,光敏剂irradiation 放射,照射conformational radiotherapy 适形放射治疗brachytherapy 短距离放射治疗stereotactic 立体定位的,立体定向的interventional radiology 介入放射学oxaliplatin 奥沙利铂doxorubicin 多柔比星gemcitabine 吉西他滨immunosuppressant 免疫抑制剂Portography 门静脉造影术contrast agent 对比剂,造影剂lipiodol 碘油Iodophor 碘伏cystic duct 胆囊管choledochal duct 胆总管choledochal cysts 胆总管囊肿Choledocholithiasis 胆总管结石hepatolithiasis 肝内胆管结石病oriental cholangiohepatitis 东方人胆管肝炎Biliary malformation 胆管畸形Liver fluke 肝吸虫protocol 治疗方案therapeutic regimen 治疗方案Palliative Treatment 姑息治疗Signs and Symptoms 体征和症状plethora 多血症,多血质Differential Diagnosis 鉴别诊断Randomized Controlled Trials 随机对照试验enterocinesia 肠动,肠蠕动Ligation 结扎术luminal obstruction 官腔阻塞screening 普检,筛查,筛选predisposing factor 易感因素enhanced susceptibility 增强易感性hyperbaric oxygen treatment 高压氧治疗asymptomatic 无症状的indolent 无痛的Intractable Pain 顽固性疼痛visceral 内脏的steatosis 脂肪变性latency 潜伏期side effects 副作用decompensation 失代偿anoxia 缺养症anoxic 缺氧的anoxemia. 缺氧血症;血缺氧ischemia 局部缺血,缺血Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury 缺血再灌注损伤ischemic change 缺血性改变anemia 贫血pyogenic 化脓的purulent 化脓性,脓性的hepatomegaly 肝肿大umbilical fissure 裂脐cytokine 细胞因子neuropeptide 神经肽neurotransmitter 神经递质fluorescence in situ hybridization 荧光原位杂交necrosis 坏死necrocytosis 细胞坏死apoptosis 凋亡apoptotic 细胞凋亡的desmoplastic reaction 纤维成形性反应oncogene 癌基因Suppressor Genes 抑制基因genetic 遗传的epigenetic change 基因外改变hypermethylation 超甲基化sequential occurrence 顺序发生stepwise 分步的,分段的,逐步的mesenchymal 间质morphology 形态atypia 非典型,异型性Phenotype 表型dehydration 脱水paraffin 石蜡impregnation 浸渍,受精,受孕embedding 包埋,埋植serial section 连续切片anesthesia 麻醉anesthesiology 麻醉学anesthetist 麻醉师palpation 触诊orifice 管口,口,小孔one orifice 一个管口intubate 插管pancreatic secretion 胰腋centrifuge 离心,,离心机cannulation 管子reactive oxygen species 活性氧recanalization 再通,再穿通Celiac Plexus 腹腔丛arteriolar 微动脉的,小动脉的Collateral Circulation 侧支循环intima 内膜subintimal 内膜下的mitochondria 线粒体multifocal 多病灶的endemic 地方性的amenable 适合的more specifically 更具体地说mainstay 主要依据kink 扭折,纽结lethal 致命的peculiarity 特性armamentarium 医疗设备,设备demarcate 划界线,分开,区别paucity 资料贫乏migration 移位interim report 中期报告nihilistic 虚无主义的enigmatic 难理解的,神秘的occult 隐匿的,潜隐的autopsy 尸检detritus 腐屑,腐质,碎屑antegrade 顺行的retrograde逆行的endogenous 内源的,内生的exogenous 外源的,外生的intracorporeal 体内的extracorporeal 体外的autocrine 自分泌paracrine 旁分泌xenogenic 异体的,异种的cryptogenic 隐原性的,原因不明的insidiously 隐袭地congenital 先天的,天生的hereditary 遗传的,遗传性的pitfall 缺陷Biliary anomalies 胆道畸形cholecystolithiasis胆囊结石cholecystitis 胆囊炎choledocholithiasis 胆总管结石total bilirubin总胆红素unconjugated bilirubin 游离胆红素conjugated bilirubin 结合胆红素bile plug 胆栓sinusoid 血窦,窦状隙sinusoidal 血窦的窦状隙的transjugular 经颈静脉的portosystemic shunt 门体分流术hepatic coma 肝昏迷hyperammonaemia 高氨血症hypoalbuminemia 低白蛋白血症neuropsychiatric 神经精神性的confusion 意识错乱,意识模糊disorientation 定向障碍astrocyte 星形胶质细胞inflammatory mediator 炎症介质neutrophil (neutrophilic granulocyte) 嗜中性粒细胞macrophage 巨噬细胞phagocyte 吞噬细胞phagocytosis 吞噬作用mitogen 促细胞分裂原,有丝分裂原reticuloendothelial system 网状内皮系统Synthase 合酶dysregulation 调节异常,失调chromosome 染色体nuclear atypia 核异型nucleotide 核苷酸mitochondria 线粒体mitochondrial 线粒体的microsome 微粒体microsomal 微粒体的detoxify 去毒, 解毒,戒烟毒detoxification 解毒(作用),脱毒,戒毒治疗carcinogen 致癌物mutagen 诱变剂,致突变原carbohydrate antigen 糖类抗原标志物,糖链抗原glycoprotein 糖蛋白extirpation 摘除malignant transformation 恶变,恶性转化forceps biopsy 钳夹活检,钳夹活检术transpapillary 经十二指肠乳头stenosis 狭窄stenotic 狭窄的patency rate 通畅率vasculature 脉管系统diffuse intravascular coagulation 弥散性血管内凝血(DIC) coagulant and fibrinolytic systems 凝血和纤溶系统circulatory disturbance 循环紊乱Vascular Permeability 血管通透性vasodilatation 血管扩张vasopressor 血管升压类药物vasopressin 加压素endothelin 内皮缩血管肽prostaglandin 前列腺素Saphenous Veins 隐静脉renin 肾素angiotensin 血管紧张素aldosterone 醛固酮oestrogen (estrin) 雌激素progestogen (progestin) 孕激素androgen (androtin) 雄激素testosterone 睾酮acute tubular necrosis 急性肾小管坏死oedema 水肿oliguria 少尿症diuretic(a) 利尿剂haemofiltration 血液滤过dialyse 透析dialysate (Dialysis Solutions) 透析液acute respiratory distress syndrome 急性呼吸窘迫综合征(ARDS) diaphragm 横隔dyspnea 呼吸困难pulmonary oedema 肺水肿ventilatory dysfunction 通气功能障碍Total Parenteral Nutrition 全胃肠外营养enteral nutrition 肠道营养malabsorption 吸收不良venoplasty 血管成形术hematoma 血肿perforation 穿孔paracentesis 穿刺,穿刺术granulomatous inflammation 肉芽肿性炎症Bacterial Translocation 细菌移位the administration of antibiotics 抗生素的应用prophylactic antibiotics 预防性抗生素synbiotic therapy 合生元治疗free radical 自由基lactate 乳酸盐malaise 不适感,全身乏力episode 发作idiopathic 特发性的,自发性的tracer 示踪剂relaparotomy 再手术mild to moderate 轻度到中度multifactorial 多因子的,多因素的iohexol 碘海醇procaine 普鲁卡因lidocaine 利多卡因analgesia 镇痛dehiscence 裂开cryopreserved 冷藏保存的discriminant analysis 判别分析cadaveric 尸体的subjects 受试者obliteration 涂去,抹消,删除milieu 环境,境界potent 有力的,有效的schematic diagram 示意图,原理图misidentification 错误认同,错认algorithm 公式,算法,推导strong echo 强回声acoustic shadow 声影hyperecho(ic) 高回声(的)isoecho(ic) 等回声(的)hypoecho(ic) 低回声(的)anecho(ic) 无回声(的)aseptic technique 无菌术asepsis 灭菌antisepsis 消毒emergency operation 急诊手术confine operation 限期手术selective operation 择期手术evidence-based medicine 循证医学polymerase chain reaction (PCR) 聚合酶链反应inquiry 问诊chief complaints 主诉history collection 病史采集history of present illness 现病史past history 既往史personal history 个人史marital history 婚姻史menstrual history 月经史child bearing history 生育史family history 家族史physical examination 体格检查inspection 视诊palpation 触诊percussion 叩诊auscultation 听诊abdominal pain 腹痛abdominal distension 腹胀diarrhea 腹泻constipation 便秘nausea 恶心vomit 呕吐stool 大便urine 小便aspiration 误吸asphyxia (apnea) 窒息atelectasis 肺不张arrhythmia 心律失常cardiac arrest 心脏骤停ventricular fibrillation 心室纤颤hyperthermia 高热hypothermia 低温Natrium (sodium) 钠Kalium (potassium) 钾Chlorine 氯Calcium 钙Magnesium 镁Phosphorus 磷ion 离子homoeostasis 体内平衡derangement 紊乱isotonic dehydration 等渗性缺水hypotonic dehydration 低渗性缺水hypertonic dehydration 高渗性缺水water intoxication 水中毒hyponatremia 低钠血症hypernatremia 高钠血症hypochloremia 低氯血症hyperchloremia 高氯血症hypokalemia 低钾血症hyperkalemia 高钾血症hypocalcemia 低钙血症hypercalcemia 高钙血症hypomagnesemia 低镁血症hypermagnesemia 高镁血症hypophosphatemia 低磷血症hyperphosphatemia 高磷血症metabolic acidosis 代谢性酸中毒metabolic alkalosis 代谢性碱中毒respiratory acidosis 呼吸性酸中毒respiratory alkalosis 呼吸性碱中毒hematocrit (Hct) 血细胞比容autologous blood transfusion 自体输血salvaged autotransfusion 回收式自体输血predeposited autotransfusion 预存式自体输血hemodiluted autotransfusion 稀释式自体输血cryoprecipitate 冷沉淀furuncle 疖furunculosis 疖病carbuncle 痈acute lymphangitis 急性淋巴管炎erysipelas 丹毒abscess 脓肿dermoid cancer 皮肤癌melanotic 黑痣melanoma 黑色素瘤lipoma 脂肪瘤neurinoma 神经鞘瘤neurofibroma 神经纤维瘤capillary hemangioma 毛细血管瘤angiocavernoma 海绵状血管瘤racemosum hemangioma 蔓状血管瘤sebum cyst 皮脂腺囊肿tetanus 破伤风gangrene 坏疽superinfection 二重感染septicemia 败血症debridement 清创术simple goiter 单纯性甲状腺肿hyperthyroidism 甲亢hypothyroidism 甲减mastitis 乳腺炎mastopathy 乳腺病,乳腺增生症mastectomy 乳房切除术teratoma 畸胎瘤inguinal hernia 腹股沟疝femoral hernia 股疝incisional hernia 切口疝umbilial hernia 脐疝hernia of linea alba 白线疝interloop abscess 肠间脓肿helicobacter pylory (HP) 幽门螺杆菌pyloric obstruction 幽门梗阻vagotomy 迷走神经切断术lymphoma 淋巴瘤duodenal diverticulum 十二指肠憩室intussusception 肠套叠polyps 息肉ulcerative colitis 溃疡性结肠炎rectal prolapse 直肠脱垂anorectal abscess 直肠肛管周围脓肿anal fistula 肛瘘anal fissure 肛裂haemorrhoids 痔internal haemorrhoids 内痔external haemorrhoids 外痔mixed haemorrhoids 混合痔annulus haemorrhoids 环形痔proctocolectomy 直肠与结肠切除术major operation 大手术omentum 网膜pancreaticobiliary 胰胆管的Bile canaliculus 胆小管mediastinum 纵隔quadrate lobe 方叶organic 有机的,器官的interferon 干扰素glomerular filtration rate 肾小球滤过率Fulminant Liver Failure 暴发性肝衰竭Nephrotic Syndrome 肾病综合征enteropathy 肠病,肠病变Esophageal cancer 食管癌gastroesophageal varices 胃食管静脉曲张Supine Position 仰卧位informed consent 知情同意sequelae 后遗症,转归demarcate 划界线,分开,区别postprandial 食后的to date 迄今为止regarding 关于serologic 血清学的Serology 血清学hepaplastin test 肝促凝血活酶试验urea 尿素heme 血红素anionic 阴离子的。

医学专业必备英语词汇现今医学分为传统医学、基于“生物-医学模式”近代发展起来的西医,20世纪西医又发展到“社会-心理-生物医学”或综合医学模式,后基因组时代系统生物学的兴起,形成了系统医学在全球的迅速发展,成为继传统医学、西医学之后中、西医学汇通的未来医学。

接下来为大家整理了医学专业必备英语词汇,希望对你有帮助哦!医学专业必备英语词汇一:医学生物学Medical Biology医学遗传学Medical Genetics系统解剖学Systematic Anatomy组织学与胚胎学Histology and Embryology人体生理学Human Physiology生物化学Biochemistry药理学Pharmacology病理生理学Pathophysiology病理学Pathology医学免疫学Medical Immunology医学微生物学Microbiology人体寄生虫学Human Parasitology流行病学Epidemiology卫生学Hygiene局部解剖学Regional Anatomy法医学Forensic Medicine实验诊断学Laboratory Diagnosis诊断学Diagnostics内科学Internal Medicine外科学Surgery妇产科学Obstetrics and Gynecology儿科学Pediatrics神经病学Neurology精神病学Psychiatry康复医学Rehabilitation Medicine中医学Chinese Traditional Medicine皮肤与性病学Dermatology and Venerology 传染病学Infectious Diseases核医学Atomic Medicine口腔解剖生理学Oral Anatomy and Physiology 口腔组织病理学Oral Histology and Pathology 口腔粘膜病学Diseases of the Oral Mucosa牙体牙髓病学Cariology And Endodontics牙周病学Periodontics口腔正畸学Orthodontics口腔修复学Prosthodontics口腔颌面外科学Oral And Maxillofacial Surgery口腔预防医学及儿童口腔医学PDPD麻醉解剖学Anesthesia Anatomy麻醉物理学Anaesthetic Physics临床麻醉学Clinical Anaesthesiology重症监护Intensive Care Therapy疼痛诊疗学Diagnosis and Treatment of Pain麻醉设备学Anesthesia Equipment医学影像学Medical Imaging影像物理学Physics of Medicine Imaging医学专业必备英语词汇二:生物药剂学与药物动力学Biopharmaceutics and Pharmacokinetics生药学Pharmacognosy天然药物化学Natural Medicine Chemistry药剂学Pharmaceutics药事管理学The Science of Pharmacy Administration护理学基础Fundamental Nursing儿科护理学Paediatric nursing内科护理学Medical Nursing外科护理学Surgical Nursing护理管理学Science of Nursing Management护理心理学Nursing Psychology急诊护理学Emergency Nursing医用物理学Medical Physics数学Mathematics体育Physical Education计算机Computer Science毛泽东思想概论Essentials of Mao Zedong Thought 邓小平理论Deng Xiao Ping Theory政治经济学Political Economy马克思主义哲学Marxism Philosophy法律基础Basis of Law医学伦理学Medicine Ethics医学心理学Medical Psychology市场营销Marketing会计学Accounting影像设备学Medical Imaging Equipment医用电子学Medical Electronics超声诊断Ultrasonic Diagnosis眼科学Ophthalmology基础眼科学Fundamental Ophthalmology临床眼科学Clinical Ophthalmology眼科手术学Ophthalmic Operative Surgery 眼科诊断学Ophthalmologic Diagnostics 耳鼻咽喉科学Otorhinolaryngology无机化学Inorganic Chemistry有机化学Organic Chemistry分析化学Analytical Chemistry物理化学Physical Chemistry仪器分析Instrumental Analysis药物化学Medicinal Chemistry药物分析Pharmaceutical Analysis。

内分泌病英文书The title of the book on endocrine disorders in English could be "Endocrine Disorders: A Comprehensive Guide" or "Understanding Endocrine Diseases: A Holistic Approach."The book would cover a wide range of topics related to endocrine disorders, including the endocrine system, hormonal imbalances, diagnostic methods, treatment options, and the impact of these disorders on various bodily functions. It would aim to provide a thorough understanding of the causes, symptoms, and management of different endocrine diseases.The book would also delve into specific endocrine disorders such as diabetes, thyroid disorders, adrenal gland disorders, pituitary gland disorders, and reproductive hormone disorders. It would explore the pathophysiology, epidemiology, and risk factors associated with each disorder, along with the latest research and advancements in their diagnosis and treatment.In addition to discussing the medical aspects of endocrine disorders, the book would also address the psychological and social implications of living with these conditions. It would explore the challenges faced by individuals with endocrine disorders, the impact on their quality of life, and strategies for coping and managing these conditions effectively.Furthermore, the book would provide practical guidance for healthcare professionals, including endocrinologists, primary care physicians, and nurses, on how to diagnose and treat endocrine disorders. It would emphasize evidence-based practices, therapeutic interventions, and multidisciplinary approaches to optimize patient care and outcomes.To enhance the reader's understanding, the book would include illustrations, diagrams, and case studies to illustrate key concepts and real-life scenarios. It would also provide references to relevant research articles and resources for further reading.Overall, this comprehensive book on endocrine disorders in English would serve as a valuable resource for healthcare professionals, medical students, researchers, and individuals seeking in-depth knowledge about these complex conditions. It would aim to promote awareness, education, and effective management of endocrine disorders for the betterment of patients' health and well-being.。

临床医学常见疾病医学英语文献阅读马志方Clinical Medicine Common Disease Medical Literature ReadingThe field of clinical medicine encompasses a vast array of diseases and conditions that affect the human body. As a medical professional, it is essential to have a thorough understanding of these prevalent diseases and their associated medical literature. In this essay, we will delve into the importance of clinical medicine common disease medical literature reading and its implications for healthcare professionals.One of the most significant benefits of reading medical literature on common clinical diseases is the opportunity to stay up-to-date with the latest advancements in the field. Medical research is constantly evolving, and new discoveries, treatment methods, and best practices are being constantly introduced. By regularly reviewing the medical literature, healthcare professionals can ensure that they are providing the most effective and evidence-based care to their patients.Moreover, clinical medicine common disease medical literature offers valuable insights into the epidemiology, etiology, andpathophysiology of these conditions. Understanding the underlying mechanisms and risk factors associated with various diseases can assist healthcare professionals in developing more targeted and personalized treatment plans. This knowledge can also contribute to the development of preventive strategies and public health initiatives aimed at reducing the burden of these diseases on the population.Another crucial aspect of clinical medicine common disease medical literature reading is the opportunity to improve diagnostic accuracy. Many common diseases present with overlapping symptoms, and accurate diagnosis is essential for effective treatment. By familiarizing themselves with the diagnostic criteria, clinical presentation, and diagnostic tools discussed in the medical literature, healthcare professionals can enhance their diagnostic skills and improve patient outcomes.Furthermore, the medical literature on common clinical diseases often includes information on the latest treatment modalities, including pharmacological interventions, surgical techniques, and alternative therapies. By staying informed about these developments, healthcare professionals can make more informed decisions about the most appropriate course of treatment for their patients, taking into consideration the latest evidence-based recommendations.In addition to the clinical benefits, reading medical literature oncommon diseases can also contribute to the professional development of healthcare providers. By engaging with the research and scholarly discourse in the field, healthcare professionals can enhance their critical thinking and problem-solving skills, as well as their ability to interpret and apply scientific evidence. This, in turn, can lead to improved patient care, better research collaborations, and the advancement of the medical profession as a whole.However, the sheer volume of medical literature available can be overwhelming, and healthcare professionals must be strategic in their approach to reading and synthesizing the information. Effective time management, efficient literature search techniques, and the ability to critically appraise the quality and relevance of the research are all essential skills for navigating the vast and ever-expanding body of medical knowledge.In conclusion, the importance of clinical medicine common disease medical literature reading cannot be overstated. By staying informed about the latest developments in the field, healthcare professionals can provide more effective, evidence-based care, improve diagnostic accuracy, and contribute to the advancement of the medical profession. As the landscape of clinical medicine continues to evolve, the ability to effectively engage with and apply the medical literature will remain a crucial skill for all healthcare providers.。

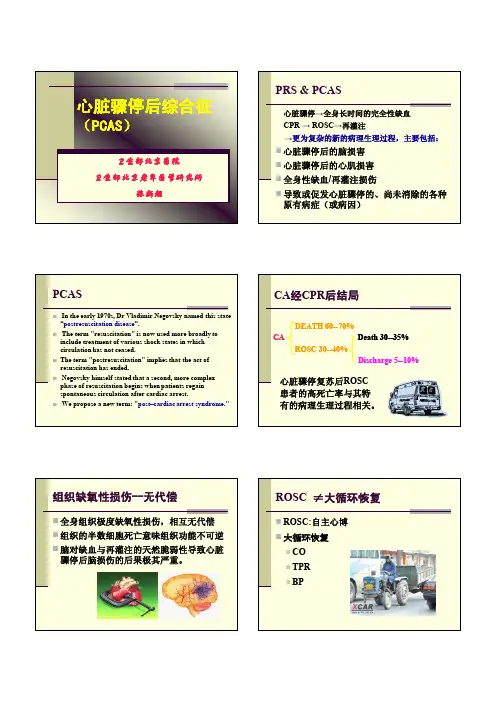

胸阻抗法无创血流动力学监测指导心肺复苏后血管活性药物的应用龚平;康健;冯薇;刘莎莎【摘要】目的评估胸阻抗法无创血流动力学的监测在心肺复苏后血管活性药物应用中的指导作用.方法选取心搏骤停后自主循环恢复的患者13例,随机分为实验组(n=7)及对照组(n=6).实验组根据胸阻抗法测定的CO值来指导血管活性药物的应用,对照组根据外周血压的变化按常规方法调整血管活性药物的应用.入院后(院外心搏骤停)或自主循环恢复后(院内心搏骤停)1、6、12、24、48和72 h监测心率、上肢动脉血压、指尖血氧饱和度和血气分析;胸阻抗法检测CO和CI;检测0 h和6 h动脉血乳酸并计算6 h乳酸清除率;72 h后进行GLS评分;观察28天存活率.结果两组患者在各时间点的心率、血压、指尖血氧饱和度和动脉血氧分压的差异无显著性意义;实验组在6、12、24、48及72 h的CO和CI均高于对照组(均P<0.05);实验组6 h乳酸清除率和72 h的GLS均高于对照组(均P<0.05);两组患者的28天存活率差异无显著性意义.结论胸阻抗法无创血流动力学的监测可以用于指导心肺复苏中血管活性药物的应用.【期刊名称】《大连医科大学学报》【年(卷),期】2013(035)005【总页数】3页(P455-457)【关键词】胸阻抗法;无创血流动力学监测;心肺复苏;血管活性药物【作者】龚平;康健;冯薇;刘莎莎【作者单位】大连医科大学,附属第一医院,急诊科,辽宁,大连,116011;大连医科大学,附属第一医院,急诊科,辽宁,大连,116011;大连医科大学,附属第一医院,急诊科,辽宁,大连,116011;大连医科大学,附属第一医院,急诊科,辽宁,大连,116011【正文语种】中文【中图分类】R459.7心肺复苏(cardiopulmonary resuscitation,CPR)患者自主循环恢复后(return of spontaneous circulation,ROSC)只有5% ~7%幸存出院[1],存活后患者可遗留不同程度的脑和心功能障碍[2],约有1/3的患者最终死于多脏器功能不全[3]。

老年带状疱疹后遗神经痛的发病因素分析及预防陈燕;丁小洁;陈星;王理;熊心猜【摘要】目的探讨年龄≥60岁的带状疱疹后遗神经痛患者发病的相关因素,为预防老年带状疱疹后遗神经痛提供临床依据.方法收集我院皮肤科住院患者168例老年带状疱疹作为研究对象,根据是否有后遗神经痛,分为带状疱疹后遗神经痛组(52例)和非带状疱疹后遗神经痛组(116例).对168例患者治疗康复过程进行临床分析,研究老年带状疱疹发病年龄、就诊时间、是否规范治疗、是否合并有基础疾病等因素与发生后遗神经痛的内在关系.结果与老年带状疱疹后遗神经痛的发病率有显著相关性的主要因素包括:发病年龄大于60岁、就诊时间大于5d、不规范治疗(单独使用抗病毒、营养神经或调节免疫等治疗手段,未联合治疗2周)和合并有基础疾病(系统性红斑狼疮、糖尿病和恶性肿瘤等).结论发病年龄大、合并基础疾病带状疱疹患者,一定要及时给予抗病毒、营养神经、调节免疫等联合治疗,达到有效预防老年带状疱疹后遗神经痛的发生、减轻老年带状疱疹患者病痛的目的.【期刊名称】《老年医学与保健》【年(卷),期】2018(024)005【总页数】3页(P494-496)【关键词】老年;带状疱疹;后遗神经痛;预防【作者】陈燕;丁小洁;陈星;王理;熊心猜【作者单位】川北医学院附属医院皮肤科,四川南充637000;川北医学院附属医院皮肤科,四川南充637000;川北医学院附属医院皮肤科,四川南充637000;川北医学院附属医院皮肤科,四川南充637000;川北医学院附属医院皮肤科,四川南充637000【正文语种】中文老年带状疱疹后遗神经痛是特指年龄≥60岁的带状疱疹后神经痛 (postherpetic neuralgia,PHN)患者,是一种带状疱疹皮疹愈合后的神经疼痛疾病,也是带状疱疹(herpeszoster,HZ)最常见的后遗症。

带状疱疹后遗神经痛的诊断有多种标准:我国研究认为皮损痊愈后疼痛≥4周[1-2]可诊断。

Pain Practice, Volume 1, Number 1, 2001 11–20Epidemiology, Pathophysiology,and Management of Complex Marco Pappagallo, MD*; Andrew D. Rosenberg, MD†*Comprehensive Pain Treatment Center and †Department of Anesthesiology, Hospital for JointDiseases, Mt. Sinai/NYU Health, New York, New YorkIn order to further the understanding of the 2 clinical entities known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD)and causalgia, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) decided to reclassify their terminol-ogy. Thus, in 1994 the IASP renamed the 2 disorders re-spectively CRPS type 1 (formerly referred to as RSD)and CRPS type 2 (the disorder previously known as causalgia, associated with a definable nerve lesion. 1 As described by Stanton-Hicks, 2 the term CRPS implies the presence of regional pain and sensory findings after a noxious event with additional abnormalities including edema and changes in skin color, temperature, and su-domotor activity. These changes all appear to be out of proportion with the physical damage from the noxious event. It must be noted that the IASP diagnostic criteria for CRPS type 1 and type 2 still await full clinical and scientific validation. 3–5Moreover, numerous practitio-ners have questioned the usefulness of these new terms.One major problem is that the diagnostic criteria for CRPS type 1 and type 2 remain too vague. This might result in overdiagnosing the 2 entities and in causing dif-ficulties with analyzing treatment outcome data.Undoubtedly, these disorders are complex and diffi-cult to understand. Pain medicine experts continue to struggle for the development of satisfactory treatment Abstract: Complex regional pain syndromes (CRPS) are challenging neuropathic pain states quite difficult to compre-hend and treat. Although not yet fully understood, advances are being made in the knowledge of the mechanisms in-volved with CRPS. Patients often present with incapacitating pain and loss of function. Patients suffering from these disor-ders need to have treatment plans tailored to their individual problems. A comprehensive diagnostic evaluation and early and aggressive therapeutic interventions are imperative. The therapeutic approach often calls for a combination of treat-ments. Medications such as antiepileptics, opioids, antidepres-sants, and topical agents along with a rehabilitation medicine program can help a major portion of patients suffering from these disorders. Implantable devices can aid those patients with CRPS. While progress is being made in treating patients with CRPS, it is important to remember that the goals of care are always to: 1) perform a comprehensive diagnostic evalua-tion, 2) be prompt and aggressive in treatment interventions,3) assess and reassess the patient’s clinical and psychological status, 4) be consistently supportive, and 5) strive for the max-imal amount of pain relief and functional improvement. In this review article, the current knowledge of the epidemiol-ogy, pathophysiology, diagnostic, and treatment methodolo-gies of CRPS are discussed to provide the pain practitioner with essential and up-to-date guidelines for the management of CRPS. Key Words: CRPS, comprehensive evaluation, aggressive therapeutic regimen, psychological support, prolonged re-habilitationAddress correspondence and reprint requests to: Marco Pappagallo,MD, Director, Comprehensive Pain Treatment Center, Hospital for Joint Diseases, 301 East 17th Street, New York, NY 10003. U.S.Aalgorithms. CRPS is a formidable challenge for pain medicine specialists as well as for affected patients. This remains true despite all the recent scientific advances in the fields of pain neurophysiology and pharmacology.In this review, we will present the most updated and relevant information on the epidemiology and patho-physiology of CRPS. We will also discuss the assessment of patients with CRPS, and the use of diagnostic tech-niques as well as propose new treatment options in its management.THE ROLE OF SYMPATHETICALLYMAINTAINED PAIN IN CRPSIn contradistinction to CRPS, sympathetically main-tained pain (SMP) is a pathogenetic mechanism and not a clinical entity. In the past, it was often misunderstood that all patients with RSD had abnormal sympathetic nervous system involvement. On the contrary, it is now understood that the majority of patients with CRPS do not have SMP. A neuropathic pain state can be main-tained by several peripheral and central nervous system (PNS, CNS) mechanisms. SMP appears to represent 1 of the PNS mechanisms (see below, Pathogenesis). SMP may be present, perhaps only temporarily, and compli-cate CRPS as well as other painful disorders including shingles, neuralgia, and metabolic or autoimmune neu-ropathies. Pain not responsive to sympathetic blockade is referred to as sympathetically independent pain (SIP). It is possible that over time a patient may present to the same physician with SMP, then SMP and SIP, and there-after SIP alone.2,6 Therefore, it should be reasserted that the diagnosis of CRPS no longer rests on the response to a sympathetic block alone.EPIDEMIOLOGY ANDPATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF CRPSKnowledge of the epidemiology of CRPS suffers from a lack of adequate prospective studies. Retrospective study on the subject by Allen, Galer, and Schwartz that includes 134 patients indicates an average age of onset at 38 years.7 In their study, patients with CRPS type 1 presented to a multidisciplinary center with an average disease dura-tion of 2.5 years. Females are affected more commonly than males (2:1). A small percentage (5%) of patients could not recall any traumatic insult precipitating their symptoms. It appears that there may be a genetic predis-position to the development of CRPS type 1, with a higher incidence in certain HLA types. Kelmer demon-strated an increased incidence of CRPS type 1 in patients with HLA DQ 1.8 Mailis and Wade noted an increased incidence of HLA A3, B7, and DR215 in patients with CRPS. A poor response to standard treatments was noted in the DR215 group.6,9A clear understanding of the pathophysiology of CRPS remains to be elucidated. It is unclear as to what ignites the disease process after the traumatic event and how an injury causes the PNS and CNS to react in an abnormal, exaggerated manner. Hypotheses include the development of ectopic nociceptive activity (occasion-ally driven by an SMP mechanism), an abnormal re-sponse to the local release of neurotrophic factors, and the occurrence of a local neuro-immunological inflam-matory process. These peripheral events can be compli-cated by temporary or long-term CNS changes such as central sensitization and then reorganization of the pain pathways at the dorsal horn level. Pathological studies in 8 patients affected by intractable CRPS type 1 demon-strated a microangiopathic process and on electron mi-croscopy the presence of C fiber axonal sprouts in at least four of the affected patients. These findings sug-gested the occurrence of a small fiber neuropathy.10 CRPS, however, is likely the expression of neurophysio-logical abnormalities affecting both the peripheral and central nervous system.11,12 A trauma may result in ec-topic repetitive discharges from the nociceptors inner-vating the injured area. Damaged A-delta and C-noci-ceptors can produce such ectopic discharges. The axons of the injured fibers develop an abnormal mechano-sen-sitivity, and, at times, an alpha-adrenoreceptor excit-ability.13,14 If a component of SMP is present it proba-bly has its origin at this point as injured nociceptors acquire alpha-adrenoreceptor excitability. Of interest, not only abnormal changes are noted in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) cells of the injured afferent axons, but also in the cell bodies of uninjured axons within the same DRG. A state of CNS hyperexcitability occurs as af-fected afferent C-fibers release large amounts of glutamate, substance P, and other neuropeptides. This results in a cen-tral sensitization state with its clinical correlates of allo-dynia and hyperalgesia.15The release of neurotrophic factors from damaged tissue may play a role in CRPS.16,17 Neurotrophic fac-tors, including nerve growth factor, induce the develop-ment of miniature axon sprouts from the endings of small nerve afferent fibers as well as from the sympa-thetic efferent nerves, and this may favor a coupling be-tween the 2 types of nerve fibers.18 If the affected noci-ceptors have begun to express alpha-adrenoreceptor excitability, the coupling may indeed favor the SMP state. Bennett has proposed that CRPS may also be asso-ciated with an abnormal neuro-immunological inflam-matory process.19 If an abnormal immune response oc-curs after an injury, inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 1-beta, IL-6, and IL-8 are released locally. These cytokines are known to induce significant changes in nociceptors, including sensitization, activation, and even axonal damage.19 An outgrowth of the concept that immunological changes may result in the occurrence of CRPS is the number of observations addressing the role of macrophages and macrophage-released cytokines in contributing to hyper-algesia and Wallerian degeneration, as well as the role of biphosphonates as a nerve treatment option for CRPS (see below).20–23In summary, while the multiple pathogeneses of CRPS have not been defined, it appears that a traumatic injury to the distal extremity of genetically predisposed individuals may initiate a process that results in a neuro-pathic “stalemate” state in the affected limb. Of interest is that in several instances CRPS appear to be main-tained by “plastic” mechanisms that can be switched off by early and aggressive therapeutic interventions. It is conceivable that these mechanisms are centered on a complex interplay of both physiological (eg, PNS and CNS sensitization of pain pathways, tissue-released neu-rotrophic factors) and pathological states (eg, neuro-immunological inflammation, expression of abnormal receptors and channels in the nociceptors membrane of the affected limbs) that can be more easily and likely rec-tified by therapeutic interventions employed early in the course of these painful states.EVALUATION OF THE PATIENT WITH CRPSPatients suffering from CRPS need to undergo a thor-ough and comprehensive evaluation so that an individu-alized treatment plan can be initiated. Treatment usually involves a long-term patient-physician relationship, re-quiring initiating a medical plan, reevaluation, and likely repeated adjustments of the treatment plan. It is important to keep the referring physician in the “loop”of medical management decision-making so that a conti-nuity of care can be guaranteed. Treatment goals in-clude satisfactory pain relief and improvement in psy-chological and physical well being.In obtaining the patient’s history, the pain medicine specialist has to determine the nature of the initiating event, and the onset and features of symptoms. While CRPS usually involves a single distal extremity, there are reports of spread to other extremities. The physician has to assess the degree and qualities of spontaneous pain and bring forth the features of allodynia and hyperalge-sia, necessary to the diagnosis of CRPS. At the time of the evaluation, the affected limb may or may not show classic CRPS changes. However, at some point in time from the disease onset, abnormalities such as skin color and temperature changes, edema, and sweating should be elicited. Patients with SMP typically present with cold hyperalgesia in the affected limb.15CRPS is likely dependent on a variety of pathogenetic mechanisms (as discussed under the section Epidemiol-ogy and Pathophysiology), and the clinical experience suggests that multiple treatment modalities are often necessary for the majority of cases. Although there is a paucity of controlled trials in the field of CRPS manage-ment, established clinical experience indicates that a few treatment modalities have some usefulness. However, in the majority of the affected patients, combinations of treatments are often needed to achieve a satisfactory treatment outcome, such as a sympatholytic procedure for SMP, a combination of pharmacological agents, phys-ical therapy and rehabilitation medicine, and for intracta-ble cases, utilization of implantable devices.THE DIAGNOSIS OF SMPUseful diagnostic tests include regional sympathetic blocks, such as the stellate ganglion block for the arm and the lumbar sympathetic block for the leg, and intra-venous sympatholytic blocks, such as the phentolamine or the bretylium blocks. Hereafter, we will describe the techniques for blocking the stellate ganglion and the lumbar sympathetic chain.Stellate Ganglion BlockThe stellate ganglion carries the sympathetic fibers to the upper extremity. It is formed from the inferior cervi-cal and the first thoracic sympathetic ganglia. The stel-late ganglion is located behind the carotid artery and in-ternal jugular vein, anterior to the longus colli muscle and approximately 2.5 cm ϫ 1 cm ϫ 0.5 cm in size. Technique. The patient is placed on the stretcher in the supine position. A folded sheet or towel is placed behind the shoulders, and the neck is extended. This maneuver places the esophagus in a direct line posterior to the tra-chea. The neck is prepped and draped, and the middle and index fingers are placed on the neck above the stern-oclavicular junction in the immediate paratracheal area. This can be done at the C7 level. Some physicians like to perform this maneuver at C6. Pulsations of the carotid artery can be appreciated. While using enough pressureto feel the deep structures of the neck, the carotid sheath and the sternocleidomastoid muscle are retracted later-ally, away from the midline. The fingers are then sepa-rated and a skin wheal is raised between the fingers. A 22-gauge 3.5 needle is advanced perpendicular to the neck until the advancing needle meets the transverse process of C7. The needle is then withdrawn by 1 mm to bring it proximal to the longus colli fascia, stabilized,and then aspirated for any blood or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). If aspiration is negative for blood or CSF, a short acting local anesthetic, eg, lidocaine, 5 mL of 1%, and a long acting anesthetic, eg, bupivacaine 10 mL of 0.25%are administered with intermittent aspiration. After fin-ishing the injection of local anesthetic, the needle is re-moved and the head of the bed is raised. See Figure 1. 24 With blockade of the stellate ganglion, ipsilateral Hor-ner’s signs occur. However, the ipsilateral upper extremity should be examined for an increase in temperature of at least 2 Њ C when compared to the temperature of the con-tralateral limb, the presence of cutaneous vasodilatation,and the absence of any signs of sensory somatic blockade (in particular along the C6, C7, and C8 dermatomes) be-fore a stellate ganglion procedure can be called specific and adequate for the diagnosis of upper limb SMP. When performing this block appropriate resuscitation equip-ment must be available. The patient may complain of some hoarseness and the sensation of a lump in the plications can include injection into the vertebral ar-tery, subarachnoid injection, pneumothorax, or brachial plexus lesion. 25Lumbar Sympathetic BlockThe sympathetic chain lies on the anterolateral aspect of the L2 vertebra. Therefore, an anesthetic injection atthis level is sufficient to obtain a sympathetic blockade of the ipsilateral lower extremity of the patient. Usually,the sympathetic trunk is located 1.5–2 inches deep to the transverse process. The major variable in performing this block is the distance from the skin to the transverse pro-cess and this depends on the body habitus of the patient. 25Technique. In performing this block, the patient is placed on the stretcher in the prone position with a pillow placed under the abdomen. Counting cephalad from the L4-5 in-terspace the L2 spinous process is identified. Alterna-tively, this site can be verified by fluoroscopy. The back is prepped and draped. A skin wheal is raised 4 cm lateral to the L2 spinous process. A needle is passed perpendic-ular to the skin until it encounters the transverse process of L2. The needle is then withdrawn and passed caudal to the transverse process of L2 in a slightly medial direc-tion. The needle can be felt to pass the vertebrae. At this point the needle tip is close to the anterolateral aspect of the L2 vertebrae. A syringe is attached to the needle and 5 mL of 1% lidocaine and 10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine are injected after aspiration is negative for blood or CSF.Aspiration is performed intermittently. 25 Another method of performing the block requires the physician to start more laterally, approximately 7–8 cm laterally, and ad-vance the needle to encounter the anterolateral aspect of the L2 vertebrae. The procedure is performed under fluo-roscopic guidance. 26 If the patient has SMP, relief should be obtained shortly after the procedure has been per-formed. An increase in skin temperature of at least 2 ЊC,increased cutaneous vasodilatation, and no signs of so-matic blockade should be noted in the ipsilateral lower limb before calling the sympatholytic procedure ade-quate for the diagnosis of SMP (Figure 2).Figure 1. (a) When performing a stellate ganglion block the carotid sheath is retracted and the neddle advanced. (b)This view demonstrates how the fingers retract the carotid sheath as the needle is ad-vanced to the stellate gan-glion.TREATMENTSPhysical Therapy and Rehabilitation Medicine Immobilization appears to be an important predis-posing factor to the development of CRPS. Therefore,once this diagnosis is entertained, the patient should be started on an aggressive program of physical and occupa-tional therapy. Early treatment seems to be very advanta-geous. 27 The goal is to make the extremity as functional as possible. If the patient is receiving a series of sympa-thetic blocks as a treatment for CRPS/SMP, it is impor-tant to employ physical therapy while the patient is ben-efiting from the sympatholytic effects of the block. In fashioning an individual treatment plan, the combina-tion of relaxation techniques, biofeedback, and cogni-tive behavioral therapy may be considered as adjuvant therapy for some patients.Pharmacological TherapiesAntiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Some AEDs have been used successfully in the treatment of neuropathic pain, and,as such, they have also been frequently used as a treat-ment modality for CRPS. Controlled clinical trials have shown efficacy of gabapentin in the treatment of pos-therpetic neuralgia and painful diabetic neuropathy. 28,29 Overall clinical experience with gabapentin in the man-agement of CRPS has also been encouraging. Of note,gabapentin act on neither GABA receptors nor sodium channels, and its analgesic mechanism of action is unclear.Trigeminal neuralgia responds well to carbamazepine,while another AED, lamotrigine, has shown some efficacy for carbamazepine-resistant trigeminal neuralgia. 30 Car-bamazepine and lamotrigine are known to block voltage-gated neuronal membrane sodium channels. An overex-pression of these channels at the site of nerve injury (ie,neuroma) or an up-regulation of a nociceptor-specific so-dium channel subtype of the affected limb may play a pathological role in the case of CRPS, in particular per-haps, in CRPS type 2. Lastly, topiramate has been anecdot-ally used with benefit in the treatment of CRPS type 1. 31Opioids, NMDA antagonists, and cannabinoids. Opi-oids are currently the most potent and effective analge-sics utilized to treat acute and chronic painful states, and as such they have been prescribed to patients suffering from intractable CRPS. Efficacy of opioid analgesics for neuropathic pain of noncancer origin has recently been established. 32,33,34 Unlike anti-inflammatory drugs, opi-oid agonists have no analgesic “ceiling dose” and do not cause direct organ damage. Except for constipation, tol-erance occurs for most of the opioid related side effects (eg, nausea, vomiting, respiratory depression, and drows-iness). Of note, studies indicate that patients on a stable opioid analgesic regimen do not report significant im-pairment in their driving ability, attention, mood, and general cognitive functioning. 35,36 Addiction (ie, a pat-tern of abnormal drug-seeking and drug-taking behav-iors for nontherapeutic purposes) and clinically relevant analgesic tolerance 36,37are rarely seen in patients whoFigure 2. The lumbar sympathetic block can be performed (a) 4cm lateral to the spinous process of L2. The needle is advanced until it encounters the transverse process fL2 and then redi-rected caudally onto the anterolateral aspect of the body of L2.Alternatively (b) starting from a point more laterally, 7–8 cm, a needle is advanced under flouroscopic guidance until the ante-rolateral aspect of L2 is encountered.receive these medications for pain control. Among the available opioid agents, methadone has unique proper-ties. It is a potent long acting mu opioid agonist with an intrinsic NMDA antagonistic effect. There is evidence gleaned from animal experiments and clinical observa-tions that NMDA receptors play an important role in the central mechanisms of hyperalgesia and chronic pain.34 Ketamine and the oral agent dextromethorphan are NMDA antagonists that may be used in conjunction with opioids in the management of severe neuropathic states characterized by allodynia and hyperalgesia. H owever, these agents, in particular ketamine, have a very narrow therapeutic window. Ketamine can easily cause intolera-ble side effects, such as hallucinations and memory im-pairment. Also of interest is the possibility that NMDA antagonists may prevent or counteract tolerance to opi-oid analgesia. These agents may be used at subclinical, and therefore safe, dosages in order to block the pro-gression of opioid tolerance.34Several lines of evidence from experimental animal studies and clinical observations indicate that cannab-inoids, including the currently available antiemetic dronab-inol, have analgesic properties. Interestingly, the coadmin-istration of inactive doses of cannabinoids in combination with inactive doses of mu opioid agonists can produce an-tinociception. Moreover, cannabinoids appear to have a predominant antiallodynic/antihyperalgesic effect. This may be quite advantageous in the treatment of some in-capacitating neuropathic pain states.38 Antidepressants. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have often been utilized in the management of chronic pain. Post-herpetic neuralgia and painful diabetic neuropathy may respond to TCAs, such as amitriptyline, nortriptyline, or desipramine.39 Despite the fact that TCAs have been frequently used for more than 30 years in the manage-ment of chronic painful states, their role as primary an-algesics in the treatment of CRPS has been quite limited and unsatisfactory. Side effects of the TCAs, such as orthostatic hypotension, confusion, cardiotoxicity, uri-nary retention, weight gain, dry mouth, and nightmares may be common and persistent, causing serious difficul-ties to patients taking these medications.5 A new antide-pressant, venlafaxine, seems to possess the analgesic prop-erties of TCAs with the advantage of having fewer side effects. While being also used for neuropathic pain, SSRIs, such as paroxetine and fluoxetine, are not as efficacious as the TCAs.5,39 Antidepressants have an important role as adjuvants in the treatment of chronic pain. While not the mainstay medications for CRPS, these agents may be very useful in the management of several comorbidities frequently affecting the CRPS patient population such as anxiety, depression, and insomnia.5Local anesthetics. Local anesthetics, eg, intravenous lidocaine or oral mexiletine, have been utilized in pa-tients with neuropathic pain.40 Mexiletine is a local an-esthetic with antiarrhytmic properties. The putative mech-anism of its analgesic action relies on the blockade of the neuronal membrane sodium channels,41,42 and in this, mexiletine is similar to some AEDs, such as carbamazepine or lamotrigine. If a cardiac conduction defect such as a 2nd or 3rd degree heart block is present, mexiletine may not be administered. In addition, if the patient is taking any anti-arrhytmic medications, a cardiology consultation should be obtained.5Topical analgesics. Capsaicin, lidocaine, and clonidine are 3 agents that can be administered topically to pro-vide pain relief in patients suffering from CRPS and neu-ropathic pain.43,44 Capsaicin, the pungent substance found in the hot chili peppers is a C-fiber/nociceptor specific neu-rotoxin. Indeed, after prolonged use of topical capsaicin, a significant decrease in cutaneous density of C-fibers occurs. Capsaicin is known to activate the vanilloid receptor, which allows calcium and sodium to enter the nerve fi-ber.45,46 Following a brief period of depolarization (cor-responding to the initial burning pain elicited by capsai-cin application), desensitization of the nociceptor fibers occurs. The duration and the degree of the desensitizing effect on the nociceptors are dose-dependent. Unfortu-nately, poor patient compliance is common with the use of capsaicin creams at low concentrations (ie, over-the-counter preparations) since application is painful and a few weeks of multiple daily applications are needed to obtain some benefit.5 The clinical experience with low-dose capsaicin creams has given overall unimpressive re-sults. H owever, the administration of a large dose of capsaicin (compounded at Ͼ1%), when given at the ap-propriate site (ie, at the presumed location of the pain generator) and under regional anesthesia, does appear to be efficacious.46 This novel method of capsaicin ad-ministration may provide a long-lasting benefit after a single application and may facilitate physical therapy and functional recovery of the affected limb. In patients suffering from SMP, transdermal clonidine has been shown to relieve allodynia in the area of patch application. Lidocaine patches have also been used in patients suffer-ing from CRPS, with some reports of benefit.47 Of note,efficacy of transdermal lidocaine has been demonstrated for postherpetic neuralgia.43Biphosphonates. It has been hypothesized that in CRPS type 1 regional osteoporosis (which has been observed to develop over time in the affected limb) as well as sen-sitization of nociceptors may be related, to some extent, to the pathological activation of osteoclasts and mac-rophages with consequent release of proinflammatory cytokinines, eg, tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin (IL) 1-beta, IL-6, and IL-8. Biphosphonates are com-monly used in the treatment of osteoporosis. Some of these agents when given intravenously and at a relatively high dose can also relieve bone pain secondary to meta-static disease. Biphosphonates such as clodronate, alen-dronate, and pamidronate may not only inhibit osteo-clastic and macrophagic activity, but also block or interfere with the macrophagic and osteoclastic release of proin-flammatory cytokinins. Of note, in the neuropathic pain model of sciatic nerve ligature, thermal hyperalgesia was significantly decreased by a biphosphonate.20 While the mechanism of action has not been totally elucidated, it has been suggested that the analgesic effect of intrave-nous biphosphonates may be mediated through the de-pletion of macrophages in the area of injury and20 the decreased release of proinflammatory cytokines.21,22,23 More recently intravenous biphosphonates have been noted to be efficacious in the treatment of CRPS. Intra-venous pamidronate was used in 10 women and 13 men with recalcitrant CRPS. A significant decrease in pain was observed.22 In a recently conducted randomized trial, Varennna et al. utilized clodronate as a 10-day intrave-nous treatment for CRPS type 1. Significant pain relief was obtained when compared to placebo controls.21 The following case report reflects a very recent anecdotal ex-perience from our institution, the Hospital for Joint Dis-eases (HJD) in New York City. It points out not only the potential useful role of intravenous biphosphonate ther-apy in the management of CRPS type 1, but also the im-portance of performing combinations of pharmacologi-cal trials according to our current understanding of CRPS pathophysiology.Case StudyA 38-year-old female sustained a traumatic injury to her right arm after a fall, which resulted in significant wrist and arm pain. The patient underwent carpal tun-nel release after the diagnosis of posttraumatic carpal tunnel syndrome was made by electrodiagnostic studies;the arm was immobilized after the procedure. A few days later, the patient began to experience a new type of pain, which she described as a severe throbbing, burning pain associated with marked skin sensitivity to light touch and air movement. Swelling of the arm and skin color changes were noted. The cast was removed and the patient was diagnosed as having CRPS type 1. She underwent multiple stellate ganglion blocks (Ͼ10 blocks), which provided a few hours of pain relief with a decrease in allodynia after each block. An MRI of the right shoul-der was unremarkable, while a MRI of the cervical spine showed a narrow left C3-C4 foramen.At the time of her presentation to the Comprehensive Pain Treatment Center at HJD (1 year after the onset of her symptoms), she was taking tramadol 100 mg PO QID, propoxyphene 60 mg PO TID PRN, amitriptyline 50 mg PO QHS, gabapentin 900 mg PO TID, Lidoderm patch QD, and ibuprofen 400-800 mg PO TID PRN. She was also applying 0.1 mg clonidine patch to the right deltoid region Q3-4 days. The patient rated her overall pain at 8 on the numerical scale 0–10 (where 0 ϭno pain and 10 ϭ the worst pain imaginable). Her neu-rological examination revealed normal cranial nerves I-XII, full strength in the nonsymptomatic limbs (strength in the right arm was formally untestable due to excruciating pain elicited by minimal movements and tactile stimuli), normal coordination on finger to nose and heel/knee/shin testing bi-laterally, 1ϩ DTRs in the asymptomatic limbs with down-going plantar responses (DTRs of the right arm were un-testable because of pain), normal gait, and a sensory examination remarkable for mechanical allodynia (prima-rily along the radial aspect of her right hand and along the lateral aspect of her forearm).Three days after her initial consultation, the patient was hospitalized for more advanced pharmacological trials and diagnostic work-up. On day #1, propoxyphene, tramadol, amitriptyline and ibuprofen were discontinued. The patient was maintained on gabapentin at the dose of 600 mg QID. She was also started on a patient controlled analgesia (PCA) titration trial of intravenous (IV) fentanyl, intravenous pamidronate 90 mg infusion QD, tizanidine 2 mg BID PRN and dextromethorphan 30 mg PO TID.On hospital day #2, the patient was still symptomatic of her allodynia. She rated her ongoing arm pain at 7 out of 10. She continued to use the IV PCA fentanyl. A transdermal fentanyl patch of 25 mcg/hour was added to her medication regimen. She complained of moderate drowsiness and moderate to severe nausea. For nausea and as analgesic adjuvant, the patient was started on dronabinol 10 mg PO BID, while for drowsiness the pa-。