Through the Tunnel

- 格式:docx

- 大小:25.72 KB

- 文档页数:10

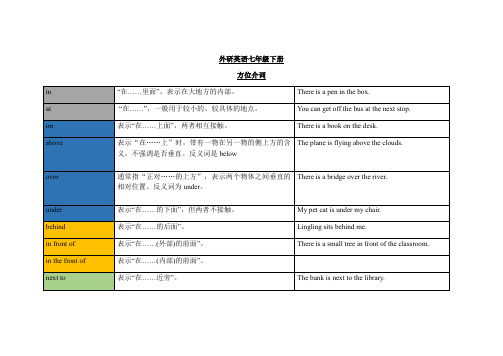

外研英语七年级下册方位介词方位介词常考考点:1. above/overover指在物体的正上方;above则指在高于某物的地方。

We are flying above the clouds.我们在云层上面飞行。

There is a lamp hanging over the table.桌子上方吊着一盏灯。

2. in/on/atin表示在某区域内、在一个空间的内部;on表示“在……上”,并与之相接触;at表示“在某地点”,强调在某个位置点。

The cat is in the box.这只猫在箱子里。

These cats are lying on the sofa.这些猫正躺在沙发上。

Jack is at home. Jack在家。

练一练:1)There is a bridge ______ the river.A.onB.beneathC.underD.over2) The window juts (伸,突) out ______ the street.A.onB.overC.belowD.under3)The plane is flying ______ the city.A.aboveB.belowC.onD.under4)Can you see the helicopter flying ______ the building?A.overB.belowC.onD.under选词填空。

1)- What can you see ______ the desk? (above/on) -I can see a computer.2)We built a little house ______ the lake. (above/on)3)There's a magazine ______ the table. (on/over)4)I like the people in the apartment ______ mine. (on/above)3. behind/in front of/in the front ofbehind表示“在……后面”;in front of表示“在某物外部的前面”;in the front of表示“在某物内部的前面”。

介词专项练习A组基础题组Ⅰ.单项选择1.Ben was helping his mother when the rain began to beat heavily the windows.A.belowB.acrossC.behindD.against2.On sunny days, my grandma often reads a novel the window.A.forB.byC.withD.from3.Volunteering is a good way to experience life the campus (校园). Take an active part in it, and you will learn more about the world.A.overB.beyondC.againstD.above4.Don’t stay inside such a sunny day. Let’s go out to enjoy the sweet flowers.A.inB.onC.byD.through5.I can hardly imagine what our life will be like the Internet in the information age nowadays.A.throughB.underC.withoutD.against6.In order to get the difficult times, it is of great importance for countries all over the world to work closely together.A.beyondB.acrossC.throughD.against7.When are you arriving I’ll pick you up the station.A.atB.toC.onD.off8.Friday afternoon, our school ends earlier than usual.A.AtB.OnC.ToD.In9.The blue planet is so far from the earth that radio signals, traveling the speed of light, take 16 hours to reach the spacecraft.A.forB.inC.onD.at10.Arthur Conan Doyle is considered a master at solving crimes.A.forB.asC.withD.by11.—How long have you been here —the end of last year.A.ByB.AtC.SinceD.In12.Peter is clever enough to read and write the age of 4.A.betweenB.atC.toD.during13.The simplest everyday activities can make a difference the environment.A.forB.inC.ofD.to14.To my pleasure, my family are always me, so I can follow my dreams with great courage.A.pastB.aboveC.uponD.behind15.If you want to be a good teacher, you should be patientstudents.A.aboutB.toC.withD.ofⅡ.词汇运用1.—Where is the city library—It’s (在……对面)the front gate of the Grand Hotel. 2.It’s so nice to take a walk on the path which leads (穿过)the trees to the river.3.The temperature in our hometown usually drops (在……以下) zero in winter.4.—Jim, I want to join the army.—Are you joking People (在……下) eighteen aren’t allowed to join the army.5.In spring, bees and butterflies play (在……中) the flowers.B组提升题组Ⅰ.单项选择1.When the accident happened the evening of last Saturday, it was blowing and raining.A.atB.onC.inD./2.—Hi, Mom directed by Jia Ling is a hit this year.—It really is. It shows us the deep love between a mother and a daughter.A./B.inC.onD.at3.—the way, can you offer me some advice on how to improve my English—Why not buy an English dictionary It can help you many ways.A.In;byB.On;inC.By;inD.By;with4.—Look! Many volunteers are recording birds’ types and changes their numbers.—I think it’s meaningful them to work here in their spare time.A.in;ofB.in;forC.on;forD.on;of5.Xinjiang cotton is praised the best cotton in our country its high quality.A.for;asB.for;byC.as;forD.by;for6.The Tom and Jerry series first appeared on screen 1940. And a new live-action(真人版)Tom and Jerry came out February 26 in the US this year.A.in;inB.in;onC.on;onD.on;in7.Since he had no tools, he had to put the picture the wall before he could put it up.A.onB.inC.againstD.over8.—I c an’t think of any other actress prettier than Audrey Hepburn.—Exactly. Her beauty is words.A.overB.beyondC.aboveD.without9.Mr. Black has gone to Shanghai on business. He will return three days.A.inB.atC.forD.on10.—How did you get the wonderful news— a Mr. Lorry, one well-informed person.A.AcrossB.IncludingC.ThroughD.ByⅡ.词汇运用1.(在……期间) his stay in Yancheng, he made some good friends.2.(没有) much work to deal with, David decided to have a drink to get relaxed.3.—What you said goes far my understanding, Miss Lee.—Sorry, I will explain it again with simple words.4.As you walk (穿过) a door, look to see if you can hold it open for someone else.5.Everyone handed in their work (除了) Li Hua because of his illness.6.—Look! The zoo is on the other side of the river.—Let’s go the bridge and see the giant pandas.拓展培优Jillian Magee, 30, is a third-grade teacher from Washington D. C. She has become very popular for her“ Tattle Box(告状盒)”.Jillian said she started to make the box because she was getting tired of being interrupted(打断)during lessons." Kids tell you every little thing that's going on. I finally told them to just write it down on paper and put it in the box,” she said.She reads the paper after school. If there's anything that's very important, she will talk to them about it. “I think the box is good for communication(交流).It helps students solve conflicts(矛盾),”Jillian said.The box helps shy students find their voice. “If they have s omething to tell me, but they're too afraid to say it themselves, they can write it down,” Jillian said. Students don't have to write their names on it. Just put it in the box, stop thinking about it and they will feel better about it.1.What makes Jillian popular2.Why did Jillian start to make the box3.What will Jillian do if there is anything important on the paper in the box4.Do students write their names on the paper5.How do you like the “Tattle Box” WhyA组基础题组Ⅰ.单项选择1.Ben was helping his mother when the rain began to beat heavily the windows.A.belowB.acrossC.behindD.against答案D句意:当雨点开始重重地敲打窗户的时候,本正在帮助他的母亲。

介词的用法(基础知识)中考经常考查的几组介词的用法时间介词:1)at表示具体的时间点(几点钟)前面用介词。

At noon, at night, at the end of at the beginning, at the moment, at the age of.I usually get up at six in the morning.。

特例:at weekends 在周末at Christmas 在圣诞节2)On表示在特定的某一天、某月某日、星期几、节日等时间的前面,We can play football on Sunday. 我们可以在星期天踢足球。

on Monday / on Sunday afternoon/ on July 24, 2015 on teachers? day3) in表示较长的一段时间,如在早上、下午、晚上;某月、某年等。

I was born in May. 我出生在五月。

They came here in 1998. 他们在1998年来这里的。

What are you going to do in the winter holiday? 寒假你打算做什么?4) for表示“一段时间”,后接与数词连用的时间名词。

翻译“达、长达”I?ve been a soldier for 5 years.我入伍已5年了。

5) during表示“在……期间”What did you do during the summer vacation?你在暑假做了什么?6) from表示“等时间的起点”,作“从……”You can come any time from Monday to Friday.周一至周五你什幺时间来都行。

The exam will start from 9:00 a.m.考试将从上午九点开始。

from 1995 to 1998.从1995年到1998年。

7) since表示“自从……以来(直到现在)”He has been away from home since 1973.他自从1973年就离开了家乡。

(完整版)⼈教精通版六下英语第⼆单元知识点总结,推荐⽂档六年级知识点总结(下册)Unit 21. in front of 在物体外部的前⾯例:There are some trees in front of the building.反义词 behind 在这个楼前有⼀些树。

in the front of 在物体内部的前⾯例:There is a desk in the front of the classroom.反义词 behind 或 at the back of 在教室的前部有⼀张书桌。

2. next to 靠近,⼏乎例: She sat next to her mother. 她坐在她妈妈的旁边。

It’s next to impossible to win the game. 要赢那场⽐赛⼏乎不可能。

3.cross ,across 和through (都有穿越,穿过的意思,⽤法不同)① cross 是动词例:I want to cross that street soon. 我想迅速穿过那条⼤街。

② across 是副词,指从⼀个平⾯的⼀端到另⼀端,如:海的⼀端到另⼀端,across the ocean,③ through 是副词,强调在三维⽴体的内部穿过.还有抽象的意义,如度过了某段时间等。

如:through the tunnel 穿过隧道4.问路的⼏个表达⽅法①How can I get to the + 你想去的地点②Where is the + 你想去的地点③Can you tell me the way to the+ 你想去的地点5.巧记时间名词前的介词的⽤法年⽉周前要⽤in ,⽇⼦前⾯却不⾏。

遇到⼏号要⽤on ,上午下午⼜是in 。

要说某⽇上下午,⽤on 换in 才能⾏。

正午夜晚⽤at ,黎明⽤它也不错。

at 也在钟点前,说“差”⽤to ,past 表⽰“过”。

6.巧记地点名词前介词的⽤法:⾥⾯、上⾯in 和on ,over ,under 上下⽅,in front of 前,behind 后,at 是在某点上。

小学英语常用介词用法第一篇:小学英语常用介词用法小学英语常用介词用法摘要:英语介词并不很多,但其用法灵活多样。

掌握常用介词的用法及常见的介词搭配,是学习英语的重点和难点。

关键词:英语介词用法介词是英语中一个十分活跃的词类,在句子的构成中起着非常重要的作用。

介词也是英语中的一个最少规则可循的词类,几乎每一个介词都可用来表达多种不同的含义;不同的介词往往又有十分相似的用法。

因此,要学好介词,最好的方法就是在掌握常用介词的基本用法的基础上,通过广泛阅读去细心地揣摩,认真地比较,归纳不同的介词的用法,方能收到良好的效果。

那么,什么是介词呢?小学常用的介词都有哪些以及它们的用法?一·介词 1 介词的含义介词又叫前置词,是一种虚词,用来表明名词,代词(或相当于名词的其他词类,短语或从句)与句中其他词关系的词。

介词不能重读,不能单独做句子成分,必须与它后面的名词或代词(或相当于名词的其他词类,短语或从句)构成介词短语,才能在句子中充当一个成分。

介词后面的名词,代词或相当于名词的部分称为介词宾语,简称介宾。

2介词的分类1)根据介词的构成形式,可将介词分为简单介词,合成介词,双重介词,短语介词四类。

而小学英语中涉及到的介词仅为简单介词和一些短语介词,如:after(在……之后),against(反对),along (沿着),among(在……之中),at(在),behind(在……后面),near(在……附近),into(在……里),in(在……内,用,戴),from(从),for(为,给),except(除……之外),by(乘,在,由,到),on the left(在左边),on the right(在右边)······2)根据介词的意义,可将介词分为表示空间关系的介词,表示时间的介词,表示原因,目的的介词,表示手段的介词和其他介词。

如:表示时间的介词in,on,at,表示方位的介词in,on,to······下文则主要是从介词的意义方面来讲介词的用法。

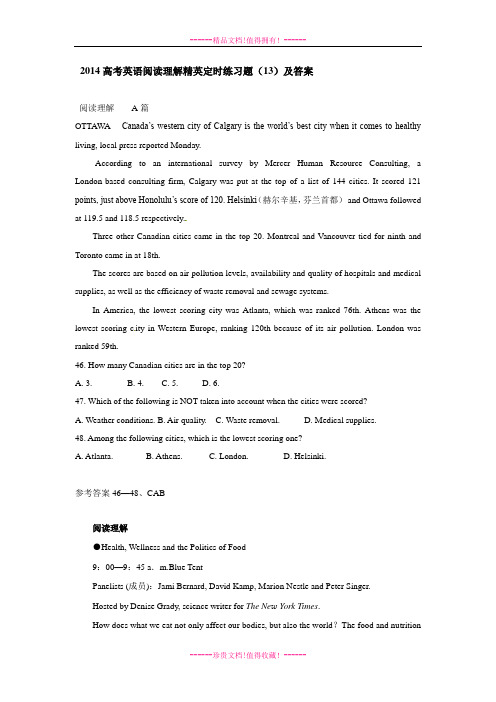

2014高考英语阅读理解精英定时练习题(13)及答案阅读理解------A篇OTTAWA -- Canada’s western city of Calgary is the world’s best city when it comes to healthy living, local press reported Monday.According to an international survey by Mercer Human Resource Consulting, a London-based consulting firm, Calgary was put at the top of a list of 144 cities. It scored 121 points, just above Honolulu’s score of 120. Helsinki(赫尔辛基,芬兰首都)and Ottawa followed at 119.5 and 118.5 respectively.Three other Canadian cities came in the top 20. Montreal and Vancouver tied for ninth and Toronto came in at 18th.The scores are based on air pollution levels, availability and quality of hospitals and medical supplies, as well as the efficiency of waste removal and sewage systems.In America, the lowest scoring city was Atlanta, which was ranked 76th. Athens was the lowest scoring c ity in Western Europe, ranking 120th because of its air pollution. London was ranked 59th.46. How many Canadian cities are in the top 20?A. 3.B. 4.C. 5.D. 6.47. Which of the following is NOT taken into account when the cities were scored?A. Weather conditions.B. Air quality.C. Waste removal.D. Medical supplies.48. Among the following cities, which is the lowest scoring one?A. Atlanta.B. Athens.C. London.D. Helsinki.参考答案46—48、CAB阅读理解●Health, Wellness and the Politics of Food9:00—9:45 a.m.Blue TentPanelists (成员):Jami Bernard, David Kamp, Marion Nestle and Peter Singer.Hosted by Denise Grady, science writer for The Ne w York Times.How does what we eat not only affect our bodies, but also the world?The food and nutritionexperts debate the role that the diet plays in both personal and global health, and present a look at food politics.●Sports Writing:For the Love of the Game9:50—10:35 a.m. Blue TentPanelists:Christine Brennan, Ira Rosen, Joe Wallace and Joe Drape.Hosted by William C.Rhoden, sports writer for The Ne w York Times.Whether catching that key moment of victory or defeat, or covering breaking news, sports writers are anything but audience.Listen as some professionals discuss the special experience in reporting of sports news.●The Art of the Review11:15—12:00 a.m.Green TentPanelists:John Freeman, Barry Gewen, David Orr, Celia McGee and Jennifer Schuessler.Hosted by Sam Tanenhaus, editor for The Ne w York Times Book Re v ie w.How much of an effect does the book review have on book sales?Join this group of critics(评论家) as they discuss the reality of book review and bestseller lists, and how they choose books for review.●New York Writers, New York Stories3:00—3:45 p.m.Green TentPanelists: Cindy Adams, Richard Cohen, Ric Klass and Lauren Redniss.Hosted by Clyde Haberman, columnist (专栏作家) for the City Section of The Ne w York Times.Join this inspiring group of New York-centric writers as they talk about why New York is a gold mine of ideas for their work.1.If you are free in the afternoon, you can attend ________.A.The Art of the ReviewB.New York Writers, New York StoriesC.Health, Wellness and the Politics of FoodD.Sports Writing: For the Love of the Game2.If you like sports writing, you will most probably ________.A.go to Blue Tent at 11:15 a.m.B.enjoy Jami Bernard's talkC.listen to Christine BrennanD.attend The Art of the Review3.Sam Tanenhaus is in charge of ________.A.The Art of the ReviewB.Health, Wellness and the Politics of FoodC.New York Writers, New York StoriesD.Sports Writing:For the Love of the Game4.All the four activities above ________.A.are about writingB.will last 45 minutes eachC.can be attended freelyD.will attract many readers5.We can learn from the text that________.A.sports writers are a type of audienceB.The Ne w York Times is popularC.Denise Grady will discuss politicsD.book reviews may affect book sales(1)Napoleon agreed to plans for a tunnel(隧道) under the English Channel in 1802. The British began digging one in 1880. Neither tunnel was completed. Europe has had to wait until the end of the 20th century for the Channel Tunnel. After nearly two centuries of dreaming, the island of Great Britain is connected to Continental Europe for the first time since the Ice Age, when the two land masses moved apart.On May 6, 1994, Britain’s Queen Elizabeth and France’s President Mitterrand carried out the official opening. The Queen was accompanied(陪同) on her train journey through the historictunnel by one of her Rolls-Royce cars which was placed on the train. The following day saw celebrations taking place in Folkestone and Calais. Regular public services did not start until the latter part of 1994.1. The island of Great Britain is _______.A. connected to France all the timeB. separated from France with a tunnelC. separated from France all the timeD. joined to France with the tunnel2. Queen Elizabeth _______ at the opening.A. took her car Rolls-Royce through the tunnelB. took her car which was placed on her train through the tunnelC. took her train through the tunnelD. took Mitterrand’s train through the tunnel3. Before 1994, one could go to Britain from France _______.A. only by shipB. by ship or planeC. by car or trainD. by ship, car or train4. Which of the following is right?A. Napoleon made plans for the tunnel.B. The public could pass through the tunnel by train after May 6, 1994.C. The tunnel was built for two centuries.D. The tunnel will do great good to Britain and France.【答案与解析】本文主要讲述拿破仑早在1802年就同意在英吉利海底修建隧道的计划,英国在1880年就开始挖掘,但都没有完成。

Through the TunnelGoing to the shore on the first morning of the holiday, the young English boy stopped at a turning of the path and looked down at a wild and rocky bay, and then over to the crowded beach he knew so well from other years. His mother walked on in front of him, carrying a bright-striped bag in one hand. Her other arm, swinging loose, was very white in the sun. The boy watched that white, naked arm, and turned his eyes, which had a frown behind them, towards the bay and back again to his mother. When she felt he was not with her, she swung round. "Oh, there you are, Jerry.”She said. She looked impatient, and then smiled. "Why, darling, would you rather not come with me? Would you rather..." She frowned, conscientiously worrying over what amusements he might secretly be longing for which she had been too busy or too careless to imagine. He was very familiar with that anxious, apologetic smile. Contrition sent him running after her. And yet, as he ran, he looked back over his shoulder at the wild bay, and all morning, as he played on the safe beach, he was thinking of it.Next morning, when it was time for the routine of swimming and sunbathing, his mother said, "Are you tired of the usual beach, Jerry? Would you like to go somewhere else?""Oh, no!" he said quickly, smiling at her out of that unfailing impulse of contrition a sort of chivalry. Yet, walking down the path with her, he blurted out , "I'd like to go and have a look at those rocks down there."She gave the idea her attention. It was a wild-looking place, and there was no one there, but she said, "Of course, Jerry. When you've had enough, come to the big beach. Or just go straight back to the villa, if you like." She walked away, that bare arm, now slightly reddened from yesterday's sun, swinging. And he almost ran after her again, feeling it unbearable that she should go by herself, but he did not.She was thinking: Of course he's old enough to be safe without me. Have I been keeping him too close? He mustn't feel he ought to be with me. I must be careful.He was an only child, eleven years old. She was a widow. She was determined to be neither possessive nor lacking in devotion. She went worrying off to her beach.As for Jerry, once he saw that his mother had gained her beach, he began the steep descent to the bay . From where he was, high up among red-brown rocks, it was a scoop of moving bluish green fringed with white. As he went lower, he saw that it spread among small promontories and inlets of rough, sharp rock, and the crisping, lapping surface showed stains of purple and darker blue. Finally, as he ran sliding and scraping down the last few yards, he saw an edge of white surf, and the shallow, luminous movement of water over white sand, and, beyond that, a solid, heavy blue.He ran straight into the water and began swimming. He was a good swimmer. He went out fast over the gleaming sand, over a middle region where rocks lay like discolored monsters under the surface, and then he was in the real sea a warm sea where irregular cold currents from the deep water shocked his limbs.When he was so far out that he could look back not only on the little bay but past the promontory that was between it and the big beach, he floated on the buoyant surface and looked for his mother. There she was a speck of yellow under an umbrella that looked like a slice of orange-peel. He swam back to shore, relieved at being sure she was there, but all atonce very lonely.On the edge of a small cape that marked the side of the bay away from the promontory was a loose scatter of rocks. Above them, some boys were stripping off their clothes. They came running, naked, down to the rocks. The English boy swam towards them, and kept his distance at a stone's throw. They were of that coast, all of them burned smooth dark brown, and speaking a language he did not understand. To be with them, of them, was a craving that filled his whole body. He swam a little closer; they turned and watched him with narrowed, alert dark eyes. Then one smiled and waved. It was enough. In a minute he had swum in and was on the rocks beside them, smiling with a desperate, nervous supplication. They shouted cheerful greetings at him, and then, as he preserved his nervous, uncomprehending smile , they understood that he was a foreigner strayed from his own beach, and they proceeded to forget him . But he was happy. He was with them.They began diving again and again from a high point into a well of blue sea between rough, pointed rocks. After they had dived and come up, they swam round, hauled themselves up , and waited their turn to dive again. They were big boys men to Jerry. He dived, and they watched him, and when he swam round to take his place, they made way for him. He felt he was accepted, and he dived again, carefully, proud of himself.Jerry dived, shot past the school of underwater swimmers , saw a black wall of rock looming at him , touched it, and bobbed up at once to the surface, where the wall was a low barrier he could see across. There was no one visible; under him, in the water, the dim shapes of the swimmers had disappeared. Then one and then another of the boys came up on the far side of the barrier of rock, and he understood that they had swum through some gap or hole in it. He plunged down again. He could see nothing through the stinging salt water but the blank rock. When he came up, the boys were all on the diving rock, preparing to attempt the feat again. And now, in a panic of failure, he yelled up, in English, "Look at me ! Look!" and he began splashing and kicking in the water like a foolish dog.They looked down gravely, frowning. He knew the frown. At moments of failure, when he clowned to claim his mother's attention, it was with just this grave, embarrassed inspection that she rewarded him. Through his hot shame, feeling the pleading grin on his face like a scar that he could never remove, he looked up at the group of big brown boys on the rock and shouted "Bonjour! Merci! Au revoir! Monsieur, monsieur!" while he hooked his fingers round his ears and waggled them.Water surged into his mouth; he choked, sank, came up. The rock, lately weighted with boys, seemed to rear up out of the water as their weight was removed. They were flying down past him, now, into the water; the air was full of falling bodies. Then the rock was empty in the hot sunlight. He counted one, two, three...At fifty he was terrified. They must all be drowning beneath him, in the watery caves of the rock! At a hundred he stared around him at the empty hillside, wondering if he should yell for help. He counted faster, faster, to hurry them up, to bring them to the surface quickly, to drown them quickly anything rather than the terror of counting on and on into the blue emptiness of the morning. And then, at a hundred and sixty, the water beyond the rock was full of boys blowing like brown whales. They swam back to the shore without a look at him.He climbed back to the diving rock and sat down, feeling the hot roughness of it under his thighs. The boys were gathering up their bits of clothing and running off along the shore toanother promontory. They were leaving to get away from him. He cried openly, fists in his eyes . There was no one to see him, and he cried himself out.It seemed to him that a long time had passed, and he swam out to where he could see his mother. Yes, she was still there, a yellow spot under an orange umbrella. He swam back to the big rock, climbed up, and dived into the blue pool among the fanged and angry boulders . Down he went, until he touched the wall of rock again. But the salt was so painful in his eyes that he could not see.He came to the surface, swam to shore, and went back to the villa to wait for his mother. Soon she walked slowly up the path, swinging her striped bag, the flushed, naked arm dangling beside her. "I want some swimming goggles, " he panted, defiant and beseeching.She gave him a patient, inquisitive look as she said casually, "Well of course, darling."But now, now, now! He must have them this minute, and no other time. He nagged and pestered until she went with him to a shop. As soon as she had bought the goggles, he grabbed them from her hand as if she were going to claim them for herself , and was off, running down the steep path to the bay.Jerry swam out to the big barrier rock, adjusted the goggles, and dived. The impact of the water broke the rubber-enclosed vacuum, and the goggles came loose. He understood that he must swim down to the base of the rock from the surface of the water. He fixed the goggles tight and firm, filled his lungs, and floated, face down, on the water. Now he could see. It was as if he had eyes of a different kind fish-eyes that showed everything clear and delicate and wavering in the bright water.Under him, six or seven feet down, was a floor of perfectly clean, shining white sand, rippled firm and hard by the tides. Two greyish shapes steered there, like long, rounded pieces of wood or slate. They were fish. He saw them nose towards each other, poise motionless, make a dart forward, swerve off, and come round again. It was like a water dance. A few inches above them, the water sparkled as if sequins were dropping through it. Fish again myriads of minute fish, the length of his finger-nail, were drifting through the water, and in a moment he could feel the innumerable tiny touches of them against his limbs. It was like swimming in flaked silver. The great rock the big boys had swum through rose sheer out of the white sand, black, tufted lightly with greenish weed. He could see no gap in it. He swam down to its base. Again and again he rose, took a big chestful of air, and went down. Again and again he groped over the surface of the rock, feeling it, almost hugging it in the desperate need to find the entrance. And then, once, while he was clinging to the black wall, his knees came up and he shot his feet out forward and they met no obstacle. He had found the hole.He gained the surface, clambered about the stones that littered the barrier rock until he found a big one , and, with this in his arms, let himself down over the side of the rock. He dropped, with the weight, straight to the sandy floor. Clinging tight to the anchor of stone, he lay on his side and looked in under the dark shelf at the place where his feet had gone. He could see the hole. It was an irregular, dark gap, but he could not see deep into it. He let go of his anchor, clung with his hands to the edges of the hole, and tried to push himself in.He got his head in, found his shoulders jammed, moved them in sidewise, and was inside as far as his waist. He could see nothing ahead. Something soft and clammy touched his mouth, he saw a dark frond moving against the greyish rock, and panic filled him. He thought of octopuses, of clinging weed. He pushed himself out backward and caught a glimpse, as heretreated, of a harmless tentacle of seaweed drifting in the mouth of the tunnel. But it was enough. He reached the sunlight, swam to shore, and lay on the diving rock. He looked down in the blue well of water. He knew he must find his way through that cave, or hole, or tunnel, and out the other side.First, he thought, he must learn to control his breathing. He let himself down into the water with another big stone in his arms, so that he could lie effortlessly on the bottom of the sea. He counted. One, two, three. He counted steadily. He could hear the movement of blood in his chest. Fifty-one, fifty-two...His chest was hurting. He let go of the rock and went up into the air. He saw that the sun was low. He rushed to the villa and found his mother at her supper. She said only "Did you enjoy yourself?" and he said "Yes".All night the boy dreamed of the water-filled cave in the rock, and as soon as breakfast was over he went to the bay.That night his nose bled badly. For hours he had been underwater, learning to hold his breath, and now he felt weak and dizzy. His mother said, "I shouldn't overdo things, darling, if I were you. "That day and the next, Jerry exercised his lungs as if everything, the whole of his life, all that he would become, depended upon it . And again his nose bled at night, and his mother insisted on his coming with her the next day. It was a torment to him to waste a day of his careful self-training, but he stayed with her on that other beach, which now seemed a place for small children, a place where his mother might lie safe in the sun. It was not his beach.He did not ask for permission, on the following day, to go to his beach. He went, before his mother could consider the complicated rights and wrongs of the matter. A day's rest, he discovered, had improved his count by ten. The big boys had made the passage while he counted a hundred and sixty. He had been counting fast, in his fright . Probably now, if he tried, he could get through that long tunnel, but he was not going to try yet. A curious, most unchildlike persistence, a controlled impatience, made him wait. In the meantime, he lay underwater on the white sand, littered now by stones he had brought down from the upper air, and studied the entrance to the tunnel. He knew every jut and corner of it, as far as it was possible to see. It was as if he already felt its sharpness about his shoulders【考点解析】1. 辨析unfailing (para.3)和lastingunfailing:(尤指优良的特性)无尽的;无穷的;永久的e.g.①with unfailing inter est 永不衰竭的兴趣;②an unfailing admirer of modern art 永远热爱现代艺术的人。

初中连词用法:1. as as作为连词,引导时间状语从句,“当……的时候”,一般用于一般过去时。

例如: As he explored the sea,he took a lot of pictures. 他在探海时,拍了许多照片。

还可以引导原因状语从句,只说明一般的因果关系,语气比because弱,说明比较明显的原因,它引导的从句通常放在句首,有时也放在句尾。

例如: As the car is expensive,we can’t buy it. 由于汽车太贵,我们买不起。

As everybody has come,we can set off. 既然大家都到了,我们可以动身了。

as soon as 一……就 例如: As soon as he arrived in France,he called me. 他一到法国,就给我打电话。

as…as… 表示双方程度相等,“和……一样”。

基本句式: A、主语+谓语(系动词)+as+原级形容词+as… 例如: Xiao Li is as tall as his brother. 小李和他哥哥一样高。

Your jacket is as new as mine. 你的茄克衫和我的一样新。

B、主语+谓语(行为动词)+as+ 原级副词 +as… 例如: He speaks French as fluently as you. 他说法语和你说得一样流利。

Wang Ying teaches maths as conscientiously as her sister.王莹教数学和她姐姐一样认真。

2. a few;few;a little;little few或a few在句中修饰可数名词,后接可数名词复数;也可用来代替复数名词。

其中few表示否定,意为“几乎没有”,a few则表示肯定,意为“有一些”。

例如: Few people lived here many years ago.许多年前几乎没有人住在这儿。

Through the TunnelBy Doris LessingGoing to the shore on the first morning of the holiday, the young English boy stopped at a turning of the path and looked down at a wild and rocky bay, and then over to the crowded beach he knew so well from other years. His mother walked on in front of him, carrying a bright-striped bag in one hand. Her other arm, swinging loose, was very white in the sun. The boy watched that white, naked arm, and turned his eyes, which had a frown behind them, toward the bay and back again to his mother. When she felt he was not with her, she swung around. "Oh, there you are, Jerry!" she said. She looked impatient, then smiled. "Why, darling, would you rather not come with me? Would you rather-" She frowned, conscientiously worrying over what amusements he might secretly be longing for which she had been too busy or too careless to imagine. He was very familiar with that anxious, apologetic smile. Contrition sent him running after her. And yet, as he ran, he looked back over his shoulder at the wild bay; and all morning, as he played on the safe beach, he was thinking of it.Next morning, when it was time for the routine of swimming and sunbathing, his mother said, "Are you tired of the usual beach, Jerry? Would you like to go somewhere else?""Oh, no!" he said quickly, smiling at her out of that unfailing impulse of contrition - a sort of chivalry. Yet, walking down the path with her, he blurted out, "I'd like to go and have a look at those rocks down there."She gave the idea her attention. It was a wild-looking place, and there was no one there, but she said, "Of course, Jerry. When you've had enough come to the big beach. Or just go straight back to the villa, if you like." She walked away, that bare arm, now slightly reddened from yesterday's sun, swinging. And he almost ran after her again, feeling it unbearable that she should go by herself, but he did not.She was thinking, Of course he's old enough to be safe without me. Have I been keeping him too close? He mustn't feel he ought to be with me. I must be careful.He was an only child, eleven years old. She was a widow. She was determined to be neither possessive nor lacking in devotion. She went worrying off to her beach.As for Jerry, once he saw that his mother had gained her beach, he began the steep descent to the bay. From where he was, high up among red-brownrocks, it was a scoop of moving bluish green fringed with white. As he went lower, he saw that it spread among small promontories and inlets of rough, sharp rock, and the crisping, lapping surface showed stains of purple and darker blue. Finally, as he ran sliding and scraping down the last few yards, he saw an edge of white surf, and the shallow, luminous movement of water over white sand, and, beyond that, a solid, heavy blue.He ran straight into the water and began swimming. He was a good swimmer. He went out fast over the gleaming sand, over a middle region where rocks lay like discoloured monsters under the surface, and then he was in the real sea - a warm sea where irregular cold currents from the deep water shocked his limbs.When he was so far out that he could look back not only on the little bay but past the promontory that was between it and the big beach, he floated on the buoyant surface and looked for his mother. There she was, a speck of yellow under an umbrella that looked like a slice of orange peel. He swam back to shore, relieved at being sure she was there, but all at once very lonely.On the edge of a small cape that marked the side of the bay away from the promontory was a loose scatter of rocks. Above them, some boys were stripping off their clothes. They came running, naked, down to the rocks. The English boy swam towards them, and kept his distance at a stone's throw. They were of that coast, all of them burned smooth dark brown, and speaking a language he did not understand. To be with them, of them, was a craving that filled his whole body. He swam a little closer; they turned and watched him with narrowed, alert dark eyes. Then one smiled and waved. It was enough. In a minute, he had swum in and was on the rocks beside them, smiling with a desperate, nervous supplication. They shouted cheerful greetings at him, and then, as he preserved his nervous, uncomprehending smile, they understood that he was a foreigner strayed from his own beach, and they proceeded to forget him. But he was happy. He was with them.They began diving again and again from a high point into a well of blue sea between rough, pointed rocks. After they had dived and come up, they swam around, hauled themselves up, and waited their turn to dive again. They were big boys — men to Jerry. He dived, and they watched him, and when he swam around to take his place, they made way for him. He felt he was accepted, and he dived again, carefully, proud of himself.Soon the biggest of the boys poised himself, shot down into the water, and did not come up. The others stood about, watching. Jerry, after waiting for the sleek brown head to appear, let out a yell of warning; they looked at him idly and turned their eyes back towards the water. After a long time, the boy came up on the other side of a big dark rock, letting the air out of his lungs in a spluttering gasp and a shout of triumph. Immediately, the rest of them dived in. One moment, the morning seemed full of chattering boys; the next, the air and the surface of the water were empty. But through the heavy blue, dark shapes could be seen moving and groping.Jerry dived, shot past the school of underwater swimmers, saw a black wall of rock looming at him, touched it, and bobbed up at once to the surface,where the wall was a low barrier he could see across. There was no one visible; under him, in the water, the dim shapes of the swimmers had disappeared. Then one, and then another of the boys came up on the far side of the barrier of rock, and he understood that they had swum through some gap or hole in it. He plunged down again. He could see nothing through the stinging salt water but the blank rock. When he came up, the boys were all on the diving rock, preparing to attempt the feat again. And now, in a panic of failure, he yelled up, in English, "Look at me! Look!" and he began splashing and kicking in the water like a foolish dog.They looked down gravely, frowning. He knew the frown. At moments of failure, when he clowned to claim his mother's attention, it was with just this grave, embarrassed inspection that she rewarded him. Through his hot shame, feeling the pleading grin on his face like a scar that he could never remove, he looked up at the group of big brown boys on the rock and shouted, "Bonjour! Merci! Au revoir! Monsieur, monsieur!"while he hooked his fingers round his ears and waggled them.Water surged into his mouth; he choked, sank, came up. The rock, lately weighed with boys, seemed to rear up out of the water as their weight was removed. They were flying down past him, now, into the water; the air was full of falling bodies. Then the rock was empty in the hot sunlight. He counted one, two, three . . . .At fifty, he was terrified. They must all be drowning beneath him, in the watery caves of the rock! At a hundred, he stared around him at the empty hillside, wondering if he should yell for help. He counted faster, faster, to hurry them up, to bring them to the surface quickly, to drown them quickly - anything rather than the terror of counting on and on into the blue emptiness of the morning. And then, at a hundred and sixty, the water beyond the rock was full of boys blowing like brown whales. They swam back to the shore without a look at him.He climbed back to the diving rock and sat down, feeling the hot roughness of it under his thighs. The boys were gathering up their bits of clothing and running off along the shore to another promontory. They were leaving to get away from him. He cried openly, fists in his eyes. There was no one to see him, and he cried himself out.It seemed to him that a long time had passed, and he swam out to where he could see his mother. Yes, she was still there, a yellow spot under an orange umbrella. He swam back to the big rock, climbed up, and dived into the blue pool among the fanged and angry boulders. Down he went, until he touched the wall of rock again. But the salt was so painful in his eyes that he could not see.He came to the surface, swam to shore and went back to the villa to wait for his mother. Soon she walked slowly up the path, swinging her striped bag, the flushed, naked arm dangling beside her. "I want some swimming goggles," he panted, defiant and beseeching.She gave him a patient, inquisitive look as she said casually, "Well, of course, darling."But now, now, now! He must have them this minute, and no other time. He nagged and pestered until she went with him to a shop. As soon as she had bought the goggles, he grabbed them from her hand as if she were going to claim them for herself, and was off, running down the steep path to the bay.Jerry swam out to the big barrier rock, adjusted the goggles, and dived. The impact of the water broke the rubber-enclosed vacuum, and the goggles came loose. He understood that he must swim down to the base of the rock from the surface of the water. He fixed the goggles tight and firm, filled his lungs, and floated, face down, on the water. Now he could see. It was as if he had eyes of a different kind —fish eyes that showed everything clear and delicate and wavering in the bright water.Under him, six or seven feet down, was a floor of perfectly clean, shining white sand, rippled firm and hard by the tides. Two greyish shapes steered there, like long, rounded pieces of wood or slate. They were fish. He saw them nose towards each other, poise motionless, make a dart forward, swerve off, and come around again. It was like a water dance. A few inches above them, the water sparkled as if sequins were dropping through it. Fish again — myriads of minute fish, the length of his fingernail, were drifting through the water, and in a moment he could feel the innumerable tiny touches of them against his limbs. It was like swimming in flaked silver. The great rock the big boys had swum through rose sheer out of the white sand, black, tufted lightly with greenish weed. He could see no gap in it. He swam down to its base.Again and again he rose, took a big chestful of air, and went down. Again and again he groped over the surface of the rock, feeling it, almost hugging it in the desperate need to find the entrance. And then, once, while he was clinging to the black wall, his knees came up and he shot his feet out forward and they met no obstacle. He had found the hole.He gained the surface, clambered about the stones that littered the barrier rock until he found a big one, and, with this in his arms, let himself down over the side of the rock. He dropped, with the weight, straight to the sandy floor. Clinging tight to the anchor of stone, he lay on his side and looked in under the dark shelf at the place where his feet had gone. He could see the hole. It was an irregular, dark gap, but he could not see deep into it. He let go of his anchor, clung with his hands to the edges of the hole, and tried to push himself in.He got his head in, found his shoulders jammed, moved them in sidewise, and was inside as far as his waist. He could see nothing ahead. Something soft and clammy touched his mouth, he saw a dark frond moving against the greyish rock, and panic filled him. He thought of octopuses, of clinging weed. He pushed himself out backward and caught a glimpse, as he retreated, of a harmless tentacle of seaweed drifting in the mouth of the tunnel. But it was enough. He reached the sunlight, swam to shore, and lay on the diving rock. He looked down into the blue well of water. He knew he mustfind his way through that cave, or hole, or tunnel, and out the other side.First, he thought, he must learn to control his breathing. He let himself down into the water with another big stone in his arms, so that he could lie effortlessly on the bottom of the sea. He counted. One, two, three. He counted steadily. He could hear the movement of blood in his chest. Fifty-one, fifty-two . . . . His chest was hurting. He let go of the rock and went up into the air. He saw that the sun was low. He rushed to the villa and found his mother at her supper. She said only "Did you enjoy yourself?" and he said "Yes."All night, the boy dreamed of the water-filled cave in the rock, and as soon as breakfast was over he went to the hay.That night, his nose bled badly. For hours he had been underwater, learning to hold his breath, and now he felt weak and dizzy. His mother said, "I shouldn't overdo things, darling, if I were you."That day and the next, Jerry exercised his lungs as if everything, the whole of his life, all that he would become, depended upon it. And again his nose bled at night, and his mother insisted on his coming with her the next day. It was a torment to him to waste a day of his careful self-training, but he stayed with her on that other beach, which now seemed a place for small children, a place where his mother might lie safe in the sun. It was not his beach.He did not ask for permission, on the following day, to go to his beach. He went, before his mother could consider the complicated rights and wrongs of the matter. A day's rest, he discovered, had improved his count by ten. The big boys had made the passage while he counted a hundred and sixty. He had been counting fast, in his fright. Probably now, if he tried, he could get through that long tunnel, but he was not going to try yet.A curious, most unchildlike persistence, a controlled impatience, made him wait. In the meantime, he lay underwater on the white sand, littered now by stones he had brought down from the upper air, and studied the entrance to the tunnel. He knew every jut and corner of it, as far as it was possible to see. It was as if he already felt its sharpness about his shoulders.He sat by the clock in the villa, when his mother was not near, and checked his time. He was incredulous and then proud to find he could hold his breath without strain for two minutes. The words "two minutes", authorized by the clock, brought the adventure that was so necessary to him close.In another four days, his mother said casually one morning, they must go home. On the day before they left, he would do it. He would do it if it killed him, he said defiantly to himself. But two days before they were to leave - a day of triumph when he increased his count by fifteen - his nose bled so badly that he turned dizzy and had to lie limply over the big rock like a bit of seaweed, watching the thick red blood flow on to the rock and trickle slowly down to the sea. He was frightened. Supposing he turned dizzy in the tunnel? Supposing he died there, trapped? Supposing —his head went around, in the hot sun, and he almost gave up. He thought he would return to the house and lie down, and next summer, perhaps, when he had another year's growth in him - then he would go through the hole.But even after he had made the decision, or thought he had, he found himself sitting up on the rock and looking down into the water, and he knew that now, this moment when his nose had only just stopped bleeding, when his head was still sore and throbbing — this was the moment when he would try. If he did not do it now, he never would. He was trembling with fear that he would not go, and he was trembling with horror at that long, long tunnel under the rock, under the sea. Even in the open sunlight, the barrier rock seemed very wide and very heavy; tons of rock pressed down on where he would go. If he died there, he would lie until one day —perhaps not before next year — those big boys would swim into it and find it blocked.He put on his goggles, fitted them tight, tested the vacuum. His hands were shaking. Then he chose the biggest stone he could carry and slipped over the edge of the rock until half of him was in the cool, enclosing water and half in the hot sun. He looked up once at the empty sky, filled his lungs once, twice, and then sank fast to the bottom with the stone. He let it go and began to count. He took the edges of the hole in his hands and drew himself into it, wriggling his shoulders in sidewise as he remembered he must, kicking himself along with his feet.Soon he was clear inside. He was in a small rock-bound hole filled with yellowish-grey water. The water was pushing him up against the roof. The roof was sharp and pained his back. He pulled himself along with his hands — fast, fast — and used his legs as levers. His head knocked againstsomething; a sharp pain dizzied him. Fifty, fifty-one, fifty-two . . . . He was without light, and the water seemed to press upon him with the weight of rock. Seventy-one, seventy-two . . . . There was no strain on his lungs. He felt like an inflated balloon, his lungs were so light and easy, but his head was pulsing.He was being continually pressed against the sharp roof, which felt slimy as well as sharp. Again he thought of octopuses, and wondered if the tunnel might be filled with weed that could tangle him. He gave himself a panicky, convulsive kick forward, ducked his head, and swam. His feet and hands moved freely, as if in open water. The hole must have widened out. He thought he must be swimming fast, and he was frightened of banging his head if the tunnel narrowed.A hundred, a hundred and one. . . The water paled. Victory filled him. His lungs were beginning to hurt. A few more strokes and he would be out. He was counting wildly; he said a hundred and fifteen, and then, a long time later, a hundred and fifteen again. The water was a clear jewel-green all around him. Then he saw, above his head, a crack running up through the rock. Sunlight was falling through it, showing the clean dark rock of the tunnel, a single mussel shell, and darkness ahead.He was at the end of what he could do. He looked up at the crack as if it were filled with air and not water, as if he could put his mouth to it to draw in air. A hundred and fifteen, he heard himself say inside his head — but he had said that long ago. He must go on into the blackness ahead, or he would drown. His head was swelling, his lungs cracking. A hundred and fifteen, a hundred and fifteen pounded through his head, and he feebly clutched at rocks in the dark, pulling himself forward, leaving the brief space of sunlit water behind. He felt he was dying. He was no longer quite conscious. He struggled on in the darkness between lapses into unconsciousness. An immense, swelling pain filled his head, and then the darkness cracked with an explosion of green light. His hands, groping forward, met nothing, and his feet, kicking back, propelled him out into the open sea.He drifted to the surface, his face turned up to the air. He was gasping like a fish. He felt he would sink now and drown; he could not swim the few feet back to the rock. Then he was clutching it and pulling himself up on it. He lay face down, gasping. He could see nothing but a red-veined, clotted dark. His eyes must have burst, he thought; they were full of blood. He tore off his goggles and a gout of blood went into the sea. His nose was bleeding, and the blood had filled the goggles.He scooped up handfuls of water from the cool, salty sea, to splash on his face, and did not know whether it was blood or salt water he tasted. After a time, his heart quieted, his eyes cleared, and he sat up. He could see the local boys diving and playing half a mile away. He did not want them. He wanted nothing but to get back home and lie down.In a short while, Jerry swam to shore and climbed slowly up the path to the villa. He flung himself on his bed and slept, waking at the sound of feet on the path outside. His mother was coming back. He rushed to the bathroom, thinking she must not see his face with bloodstains, or tearstains, on it. He carne out of the bathroom and met her as she walked into the villa, smiling, her eyes lighting up. "Have a nice morning?" she asked, laying her head on his warm brown shoulder a moment."Oh, yes, thank you," he said."You look a bit pale." And then, sharp and anxious. "How did you bang your head?""Oh, just banged it," he told her.She looked at him closely. He was strained. His eyes were glazed-looking. She was worried. And then she said to herself, "Oh, don't fuss! Nothing can happen. He can swim like a fish."They sat down to lunch together."Mummy," he said, "I can stay under water for two minutes —three minutes, at least."It came bursting out of him."Can you, darling?" she said. "Well, I shouldn't overdo it. I don't think you ought to swim any more today."She was ready for a battle of wills, but he gave in at once. It was no longer of the least importance to go to the bay.。