The phase diagram and the structure of CDW state in high magnetic field in quasi-1D materia

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:325.78 KB

- 文档页数:14

铁碳相图中平衡相和平衡组织的计算作者:朱守琴来源:《世界家苑》2018年第10期摘要:铁碳相图是铁碳合金的平衡相图,通过铁碳相图根据杠杆定律可以计算铁碳合金中的各平衡相的含量和各平衡组织的含量,可以大致的分析出铁碳合金不同性能原因。

其中铁碳合金的硬度主要和相的组成有关,相的计算可以公式化。

而强度、塑韧性等性能主要与组织有关,组织的计算需分析铁碳合金的平衡结晶过程。

关键词:平衡相图;杠杆定律;平衡相;平衡组织Calculation of equilibrium phase and equilibrium structure in iron carbon phase diagramZHU Shou-qinMechanical and Electronic Engineering College Chaohu University,chaohu 238000,China) Abstract:The iron-carbon phase diagram is the equilibrium phase diagram of the iron-carbon alloy.According to lever law,the content of each equilibrium phase and the content of eachequilibrium structure in the iron-carbon alloy can be calculated by the iron-carbon phase diagram.Thecause of different properties of iron-carbon alloy can be roughly analyzed.The hardness ofiron-carbon alloy is mainly related to the composition of phase,and the calculation of phase can be formulated.The properties of strength,plasticity and toughness are mainly related to the microstructure.The equilibrium crystallization process of Fe-C alloy should be analyzed in order to calculate the microstructure.Key words:equilibrium phase diagram,lever law,equilibrium phase,equilibrium organization1.引言鐵碳合金相图是研究铁碳合金的重要工具,铁碳合金是应用广泛的工程材料,因此学好铁碳相图是从事各类加工和热处理的基础。

adhesive[胶]allotropic[同素异形的amorphous[无定形的,非晶的anion[负离子]apuy[适当地]austenite[奥氏体]bainte「贝氏体binary isomorphous system[二元匀晶系统]Burgers vector[柏氏矢量]cadmium[镉]canon[正离子]carbide[碳化物Cast Iron[铸铁cementite[渗碳体]ceramic[陶瓷]chloride[氯chromium[铬]composite materials[复合材料cordinate system[坐标系统covalent bond[共价键crystal structure[晶体结构]crystallinity[结晶度ddiy[塑性deteriorative[劣化]dislocation[位错]edge dislocation[刃形位错]equilibrium[平衡]eutectic[共晶的eutectoid[共析的ferrite[铁素体fractional[分数的,部分的,相对的gain[晶粒grain boundary[晶界hase[相hexagonal dose-packed[密排六方的hexagonal[六方的]hypereutectoid[过共析hypoeutectoid[亚共析ion[硅Ionic Dond[离子键]isotherm[等温线lamellae[薄片]lattice[空间点阵,晶格]lever law[杠杆定律liquidus line[液相线martensite[马氏体]martensitic transformation[马氏体相变metallic bond[金属键]microstucture[显微组织monoclinic[单斜的nickel[镍nitride[氮化物]non-crystalline[非晶的]orthorhombic[正交的]parentheses[括孤]pearlite[珠光体periodic table[元素周期表phase diagram[相图]」phase transformation[相交]」point defect[点缺陷]polarize[极化polyethylene[聚乙烯polymerization[聚合]prism[棱镜]proeutectoid[先共析体provoke[诱发]reciprocal[倒数recrystallization[再结晶rhombohedral[菱方的screw dislocation[螺形位错]skew[歪斜]smal-(or low)angle grain boundary[小角度晶界sodium[钠solar cell [太阳能电池]solid solution strengthening[固溶强化solidus line[固相线solute[溶质solvus line[溶解度曲线spiral[螺旋形的]stifness[刚度]strucure[组织]synthesis[合成tetragonal[四方的tetrahedron[四面体thermoplastics[热塑性塑料]thermosets[热固性塑料tie linc[连接线]tilt boundary[倾侧晶界]translucent[半透明的]triclinic[三斜的troley[石油twin boundary[李晶界unit cell[晶胞vacancy[空位valence electron[价电子]Van de Waals bond[范德华键①材料科学是研究材料的加工、组织、性能和功能之间关系的科学。

由三元相图计算活度翟玉春【摘要】The activities formulas of all the points, lines and areas were calculated from the eight typical ternary phase diagrams by means of the melting point free energy method, standard free energy of formation method and chemical equilibrium method. No assumptions and approximations were introduced. The eight typical phase diagrams studied almost cover the whole range of ternary phase diagrams. The calculation methods and formulas could be applied to all kinds of complicated ternary phase diagrams. Additionally, this method could also be widely applied to the ternary isothermal section phase diagrams and multi-component phase diagrams.%采用熔化自由能法、标准生成自由能法和化学平衡法推导出利用8种类型的三元相图计算活度的公式,覆盖了三元相图的点、线、面全部范围.公式本身没有引进假设和近似.这8种类型的三元相图涵盖了有液相面各种类型的三元相图.本研究的计算方法和计算公式可以应用于各种复杂的三元相图,该方法也可以推广到三元等温截面相图和三元以上的多元相图.【期刊名称】《中国有色金属学报》【年(卷),期】2011(021)010【总页数】10页(P2687-2696)【关键词】三元相图;活度;计算;熔化自由能法;标准生成自由能法;化学平衡法【作者】翟玉春【作者单位】东北大学材料与冶金学院,沈阳110819【正文语种】中文【中图分类】TF01活度是重要的热力学数据,活度的测量,尤其是高温体系活度的测量费时、费钱、费力,且不易准确。

Biophysical Chemistry 109(2004)105–1120301-4622/04/$-see front matter ᮊ2003Elsevier B.V .All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.bpc.2003.10.021Cloud-point temperature and liquid–liquid phase separation ofsupersaturated lysozyme solutionJie Lu *,Keith Carpenter ,Rui-Jiang Li ,Xiu-Juan Wang ,Chi-Bun Ching a ,a a b bInstitute of Chemical and Engineering Sciences,Ayer Rajah Crescent 28,࠻02-08,Singapore 139959,Singapore aChemical and Process Engineering Center,National University of Singapore,Singapore 117576,SingaporebReceived 31July 2003;received in revised form 8October 2003;accepted 16October 2003AbstractThe detailed understanding of the structure of biological macromolecules reveals their functions,and is thus important in the design of new medicines and for engineering molecules with improved properties for industrial applications.Although techniques used for protein crystallization have been progressing greatly,protein crystallization may still be considered an art rather than a science,and successful crystallization remains largely empirical and operator-dependent.In this work,a microcalorimetric technique has been utilized to investigate liquid–liquid phase separation through measuring cloud-point temperature T for supersaturated lysozyme solution.The effects of cloud ionic strength and glycerol on the cloud-point temperature are studied in detail.Over the entire range of salt concentrations studied,the cloud-point temperature increases monotonically with the concentration of sodium chloride.When glycerol is added as additive,the solubility of lysozyme is increased,whereas the cloud-point temperature is decreased.ᮊ2003Elsevier B.V .All rights reserved.Keywords:Biocrystallization;Microcalorimetry;Cloud-point temperature;Liquid–liquid phase separation1.IntroductionKnowledge of detailed protein structure is essen-tial for protein engineering and the design of pharmaceuticals.Production of high-quality pro-tein crystals is required for molecular structure determination by X-ray crystallography.Although considerable effort has been made in recent years,obtaining such crystals is still difficult in general,and predicting the solution conditions where pro-*Corresponding author.Tel.:q 65-6874-4218;fax:q 65-6873-4805.E-mail address:lujie@.sg (J.Lu ).teins successfully crystallize remains a significant obstacle in the advancement of structural molecu-lar biology w 1x .The parameters affecting protein crystallization are typically reagent concentration,pH,tempera-ture,additive,etc.A phase diagram can provide the method for quantifying the influence of solu-tion parameters on the production of crystals w 2,3x .To characterize protein crystallization,it is neces-sary to first obtain detailed information on protein solution phase behavior and phase diagram.Recently physics shows that there is a direct relationship between colloidal interaction energy106J.Lu et al./Biophysical Chemistry109(2004)105–112and phase diagram.Gast and Lekkerkerker w4,5x have indicated that the range of attraction between colloid particles has a significant effect on the qualitative features of phase diagram.A similar relationship should hold for biomacromolecules, i.e.the corresponding interaction potentials govern the macromolecular distribution in solution,the shape of the phase diagram and the crystallization process w6x.Many macromolecular crystallizations appear to be driven by the strength of the attractive interactions,and occur in,or close to,attractive regimes w7,8x.Recent intensive investigation has revealed that protein or colloidal solution possesses a peculiar phase diagram,i.e.liquid–liquid phase separation and sol–gel transition exists in general in addition to crystallization w9,10x.The potential responsible for the liquid–liquid phase separation is a rather short range,possibly van der Waals,attractive potential w11,12x.The measurement of cloud-point temperature T can provide useful informationcloudon the net attractive interaction between protein molecules,namely,the higher the cloud-point tem-perature,the greater the net attractive interaction. Herein Taratuta et al.w13x studied the effects of salts and pH on the cloud-point temperature of lysozyme.Broide et al.w14x subsequently meas-ured the cloud-point temperature and crystalliza-tion temperature for lysozyme as a function of salt type and concentration.From these works the cloud-point temperature was found to be typically 15–458C below the crystallization temperature. Furthermore,Muschol and Rosenberger w15x deter-mined the metastable coexistence curves for lyso-zyme through cloud-point measurements,and suggested a systematic approach to promote pro-tein crystallization.In general,an effective way to determine the strength of protein interactions is to study temperature-induced phase transitions that occur in concentrated protein solutions.Liquid–liquid phase separation can be divided into two stages w11x:(1)the local separation stage at which the separation proceeds in small regions and local equilibrium is achieved rapidly;and(2) the coarsening stage at which condensation of these small domains proceeds slowly to reduce the loss of interface free energy w16x.The coexisting liquid phases both remain supersaturated but differ widely in protein concentration.The effect of a metastable liquid–liquid phase separation on crystallization remains ambiguous w17x.Molecular dynamics simulations and analyt-ical theory predict that the phase separation will affect the kinetics and the mechanisms of protein crystal nucleation w18x.tenWolde and Frenkel w19x have demonstrated that the free energy barrier for crystal nucleation is remarkably reduced at the critical point of liquid–liquid phase separation, thus in general,after liquid–liquid phase separa-tion,crystallization occurs much more rapidly than in the initial solution,which is typically too rapid for the growth of single crystal with low defect densities w15x.The determination of the location of liquid–liquid phase separation curve is thus crucial for efficiently identifying the optimum solution conditions for growing protein crystals. Microcalorimetry has the potential to be a useful tool for determining:(1)the metastable-labile zone boundary;(2)the temperature-dependence of pro-tein solubility in a given solvent;and(3)the crystal-growth rates as a function of supersatura-tion w20x.Microcalorimeters can detect a power signal as low as a few microwatts whereas standard calorimeters detect signals in the milliwatt range. Because of this greater sensitivity,samples with small heat effects can be analyzed.In addition, microcalorimetry has the advantage of being fast, non-destructive to the protein and requiring a relatively small amount of material.The present work is concerned with the analysis of the transient heat signal from microcalorimeter to yield liquid–liquid phase separation information for lysozyme solutions at pH4.8.To further examine the role of salt and additive on interprotein interactions, cloud-point temperature T has been determinedcloudexperimentally as a function of the concentrations of salt,protein and glycerol.2.Materials and methods2.1.MaterialsSix times crystallized lysozyme was purchased from Seikagaku Kogyo,and used without further107J.Lu et al./Biophysical Chemistry 109(2004)105–112purification.All other chemicals used were of reagent grade,from Sigma Chemical Co.2.2.Preparation of solutionsSodium acetate buffer (0.1M )at pH 4.8was prepared with ultrafiltered,deionized water.Sodi-um azide,at a concentration of 0.05%(w y v ),was added to the buffer solution as an antimicrobial agent.Protein stock solution was prepared by dissolving protein powder into buffer.To remove undissolved particles,the solution was centrifuged in a Sigma centrifuge at 12000rev.y min for 5–10min,then filtered through 0.22-m m filters (Mil-lex-VV )into a clean sample vial and stored at 48C for further experiments.The concentration of protein solution was determined by measuring the absorbance at 280nm of UV spectroscopy (Shi-madzu UV-2550),with an extinction coefficient of 2.64ml y (mg cm )w 21x .Precipitant stock solution was prepared by dissolving the required amount of sodium chloride together with additive glycerol into buffer.The pH of solutions was measured by a digital pH meter (Mettler Toledo 320)and adjusted by the addition of small volumes of NaOH or HAc solution.2.3.Measurement of solubilitySolubility of lysozyme at various temperatures and precipitant y additive concentrations was meas-ured at pH 4.8in 0.1M acetate buffer.Solid–liquid equilibrium was approached through both crystallization and dissolution.Dissolving lasted 3days,while the period of crystallization was over 2weeks.The supernatant in equilibrium with a macroscopically observable solid was then filtered through 0.1-m m filters (Millex-VV ).The concen-tration of diluted supernatant was determined spec-troscopically and verified by refractive meter(Kruss)until refractive index remained unchanged ¨at equilibrium state.Solubility of each sample was measured in duplicate.2.4.Differential scanning microcalorimetry Calorimetric experiments were performed with a micro-differential scanning calorimeter with anultra sensitivity,micro-DSC III,from Setaram SA,France.The micro-DSC recorded heat flow in microwatts vs.temperature,thus can detect the heat associated with phase transition during a temperature scan.The sample made up of equal volumes of protein solution and precipitant solu-tion was filtered through 0.1-m m filters to remove dust particles further.To remove the dissolved air,the sample was placed under vacuum for 3min while stirring at 500rev.y min by a magnetic stirrer.The degassed sample was placed into the sample cell of 1.0ml,and a same concentration NaCl solution was placed into the reference cell.The solutions in the micro-DSC were then cooled at the rate of 0.28C y min.After every run,the cells were cleaned by sonicating for 10–15min in several solutions in the following order:deionized water,methanol,ethanol,acetone,1M KOH and finally copious amounts of deionized water.This protocol ensured that lysozyme was completely removed from the cells.The cells were then placed in a drying oven for several hours.The rubber gaskets were cleaned in a similar manner except acetone and 1M KOH were omitted and they were allowed to dry at low temperature.3.Results and discussionA typical micro-DSC scanning experiment is shown in Fig.1.The onset of the clouding phe-nomenon is very dramatic and easily detected.The sharp increase in the heat flow is indicative of a liquid–liquid phase separation process producing a latent heat.This is much consistent with many recent investigations of the liquid–liquid phase separation of lysozyme from solution w 22,23x .In fact,such a liquid–liquid phase separation is a phase transition with an associated latent heat of demixing.In this work,the cloud-point tempera-tures at a variety of lysozyme,NaCl and glycerol concentrations are determined by the micro-DSC at the scan rate of 128C y h.3.1.Effect of protein concentrationIn semilogarithmic Fig.2we plot the solid–liquid and liquid–liquid phase boundaries for lyso-108J.Lu et al./Biophysical Chemistry 109(2004)105–112Fig.1.Heat flow of a typical micro-DSC scan of lysozyme solution,50mg y ml,0.1M acetate buffer,pH 4.8,3%NaCl.The scan rate 128C y h is chosen referenced to the experimental results of Darcy and Wiencek w 23x .Note the large deflection in the curve at approximately 4.38C indicating a latent heat resulting from demixing (i.e.liquid–liquid phase separation )process.Fig.2.Cloud-point temperature and solubility determination for lysozyme in 0.1M acetate buffer,pH 4.8:solubility (5%NaCl )(s );T (5%NaCl,this work )(d );T (5%cloud cloud NaCl,the work of Darcy and Wiencek w 23x )(*);solubility (3%NaCl )(h );T (3%NaCl )(j ).cloud Fig.3.Cloud-point temperature determination for lysozyme as a function of the concentration of sodium chloride,50mg y ml,0.1M acetate buffer,pH 4.8.zyme in 0.1M acetate buffer,pH 4.8,for a range of protein concentrations.It is worth noting that,at 5%NaCl,our experimental data of T from cloud micro-DSC are quite consistent with those from laser light scattering and DSC by Darcy and Wiencek w 23x ,with difference averaging at approx-imately 0.88C.This figure demonstrates that liquid–liquid phase boundary is far below solid–liquid phase boundary,which implies that the liquid–liquid phase separation normally takes place in a highly metastable solution.In addition,cloud-point temperature T increases with the cloud concentration of protein.3.2.Effect of salt concentrationFig.3shows how cloud-point temperature changes as the concentration of NaCl is varied from 2.5to 7%(w y v ).The buffer is 0.1M acetate (pH 4.8);the protein concentration is fixed at 50mg y ml.Over the entire range of salt concentrations studied,the cloud-point temperature strongly depends on the ionic strength and increases monotonically with the concentration of NaCl.Crystallization is driven by the difference in chemical potential of the solute in solution and in the crystal.The driving force can be simplified as w 24xf sy Dm s kT ln C y C (1)Ž.eq109J.Lu et al./Biophysical Chemistry 109(2004)105–112Fig.4.The driving force required by liquid–liquid phase sep-aration as a function of the concentration of sodium chloride,50mg y ml lysozyme solution,0.1M acetate buffer,pH 4.8.In the same way,we plot the driving force,f ,required by liquid–liquid phase separation as a function of the concentration of sodium chloride in Fig.4.At the moderate concentration of sodium chloride,the driving force required by liquid–liquid phase separation is higher than that at low or high salt concentration.As shown in Fig.3,with NaCl concentration increasing,the cloud-point temperature increases,which is in accord with the results of Broide et al.w 14x and Grigsby et al.w 25x .It is known that protein interaction is the sum of different potentials like electrostatic,van der Waals,hydrophobic,hydration,etc.The liquid–liquid phase separation is driven by a net attraction between protein molecules,and the stronger the attraction,the higher the cloud-point temperature.Ionic strength is found to have an effect on the intermolecular forces:attractions increase with ionic strength,solubility decreases with ionic strength,resulting in the cloud-point temperature increases with ionic strength.It is worth noting that,the effect of ionic strength on cloud-point temperature depends strongly on the specific nature of the ions w 13x .Kosmotropic ions bind adjacent water molecules more strongly than water binds itself.When akosmotropic ion is introduced into water,the entro-py of the system decreases due to increased water structuring around the ion.In contrast,chaotropes bind adjacent water molecules less strongly than water binds itself.When a chaotrope is introduced into water,the entropy of the system increases because the water structuring around the ion is less than that in salt-free water.This classification is related to the size and charge of the ion.At high salt concentration ()0.3M ),the specific nature of the ions is much more important w 25x .The charges on a protein are due to discrete positively and negatively charged surface groups.In lysozyme,the average distance between thesecharges is approximately 10Aw 26x .As to the salt ˚NaCl used as precipitant,Na is weakly kosmo-q tropic and Cl is weakly chaotropic w 27x .At low y NaCl concentrations,as the concentration of NaCl increases,the repulsive electrostatic charge–charge interactions between protein molecules decrease because of screening,resulting in the increase of cloud-point temperature.While at high NaCl con-centrations,protein molecules experience an attrac-tion,in which differences can be attributed to repulsive hydration forces w 14,25x .That is,as the ionic strength increases,repulsive electrostatic or hydration forces decrease,protein molecules appear more and more attractive,leading to higher cloud-point temperature.At various salt concentra-tions,the predominant potentials reflecting the driving force for liquid–liquid phase separation are different.Fig.4shows that the driving force,f ,is parabolic with ionic strength,while Grigsby et al.w 25x have reported that f y kT is linear with ionic strength for monovalent salts.The possible reasons for that difference include,their model is based on a fixed protein concentration of 87mg y ml,which is higher than that used in our study,yet f y kT is probably dependent on protein concentration,besides the solutions at high protein and salt concentrations are far from ideal solutions.3.3.Effect of glycerolFig.5compares cloud-point temperature data for 50mg y ml lysozyme solutions in absence of glycerol and in presence of 5%glycerol,respec-110J.Lu et al./Biophysical Chemistry109(2004)105–112parison of cloud-point temperatures for lysozyme at different glycerol concentrations as a function of the con-centration of sodium chloride,50mg y ml,0.1M acetate buffer, pH4.8:0%glycerol(s);5%glycerol(j).Fig.6.Cloud-point temperatures for lysozyme at different glycerol concentrations,50mg y ml lysozyme,5%NaCl,0.1M acetate buffer,pH4.8.Fig.7.Cloud-point temperature and solubility determination for lysozyme at different concentrations of glycerol in0.1M acetate buffer,5%NaCl,pH4.8:solubility(0%glycerol)(s); T(0%glycerol)(d);solubility(5%glycerol)(h);cloudT(5%glycerol)(j).cloudtively.Fig.6shows the cloud-point temperature as a function of the concentration of glycerol.The cloud-point temperature is decreased as the addi-tion of glycerol.In semilogarithmic Fig.7we plot the solid–liquid and liquid–liquid phase boundaries at dif-ferent glycerol concentrations for lysozyme in0.1 M acetate buffer,5%NaCl,pH4.8,for a range of protein concentration.This figure demonstrates that liquid–liquid and solid–liquid phase bounda-ries in the presence of glycerol are below those in absence of glycerol,and the region for growing crystals is narrowed when glycerol is added. Glycerol has the property of stabilizing protein structure.As a result,if crystallization occurs over a long period of time,glycerol is a useful candidate to be part of the crystallization solvent and is often included for this purpose w28x.In addition,glycerol is found to have an effect on the intermolecular forces:repulsions increase with glycerol concentra-tion w29x.Our experiment results of solubility and cloud-point temperature can also confirm the finding.The increased repulsions induced by glycerol can be explained by a number of possible mecha-nisms,all of which require small changes in the protein or the solvent in its immediate vicinity.The addition of glycerol decreases the volume of protein core w30x,increases hydration and the size of hydration layer at the particle surface w31,32x. In this work,we confirm that glycerol shifts the solid–liquid and liquid–liquid phase boundaries. The effect of glycerol on the phase diagram strong-111 J.Lu et al./Biophysical Chemistry109(2004)105–112ly depends on its concentration and this canprovide opportunities for further tuning of nuclea-tion rates.4.ConclusionsGrowing evidence suggests protein crystalliza-tion can be understood in terms of an order ydisorder phase transition between weakly attractiveparticles.Control of these attractions is thus keyto growing crystals.The study of phase transitionsin concentrated protein solutions provides one witha simple means of assessing the effect of solutionconditions on the strength of protein interactions.The cloud-point temperature and solubility datapresented in this paper demonstrate that salt andglycerol have remarkable effects on phase transi-tions.The solid–liquid and liquid–liquid bounda-ries can be shifted to higher or lower temperaturesby varying ionic strength or adding additives.Ourinvestigation provides further information upon therole of glycerol used in protein crystallization.Glycerol can increase the solubility,and decreasethe cloud-point temperature,which is of benefit totuning nucleation and crystal growth.In continuingstudies,we will explore the effects of other kindsof additives like nonionic polymers on phasetransitions and nucleation rates.Much more theo-retical work will be done to fully interpret ourexperimental results.AcknowledgmentsThis work is supported by the grant from theNational Natural Science Foundation of China(No.20106010).The authors also thank Professor J.M.Wiencek(The University of Iowa)for kinddiscussion with us about the thermal phenomenaof liquid–liquid phase separation.Referencesw1x A.McPherson,Current approaches to macromolecular crystallization,Eur.J.Biochem.189(1990)1–23.w2x A.M.Kulkarni, C.F.Zukoski,Nanoparticle crystal nucleation:influence of solution conditions,Langmuir18(2002)3090–3099.w3x E.E.G.Saridakis,P.D.S.Stewart,L.F.Lloyd,et al., Phase diagram and dilution experiments in the crystal-lization of carboxypeptidase G2,Acta Cryst.D50(1994)293–297.w4x A.P.Gast, C.K.Hall,W.B.Russel,Polymer-induced phase separations in non-aqueous colloidal suspensions,J.Colloid Interf.Sci.96(1983)251–267.w5x H.N.W.Lekkerkerker,W.C.K.Poon,P.N.Pusey,et al., Phase-behavior of colloid plus polymer mixtures,Euro-phys.Lett.20(1992)559–564.w6x A.Tardieu,S.Finet,F.Bonnete,Structure of the´macromolecular solutions that generate crystals,J.Cryst.Growth232(2001)1–9.w7x D.Rosenbaum,C.F.Zukoski,Protein interactions and crystallization,J.Cryst.Growth169(1996)752–758.w8x A.George,W.W.Wilson,Predicting protein crystalli-zation from a dilute solution property,Acta Cryst.D50(1994)361–365.w9x D.Rosenbaum,P.C.Zamora, C.F.Zukoski,Phase-behavior of small attractive colloidal particles,Phys.Rev.Lett.76(1996)150–153.w10x V.J.Anderson,H.N.W.Lekkerkerker,Insights into phase transition kinetics from colloid science,Nature416(2002)811–815.w11x S.Tanaka,K.Ito,R.Hayakawa,Size and number density of precrystalline aggregates in lysozyme crys-tallization process,J.Chem.Phys.111(1999)10330–10337.w12x D.W.Liu,A.Lomakin,G.M.Thurston,et al.,Phase-separation in multicomponent aqueous-protein solutions,J.Phys.Chem.99(1995)454–461.w13x V.G.Taratuta,A.Holschbach,G.M.Thurston,et al., Liquid–liquid phase separation of aqueous lysozymesolutions:effects of pH and salt identity,J.Phys.Chem.94(1990)2140–2144.w14x M.L.Broide,T.M.Tominc,M.D.Saxowsky,Using phase transitions to investigate the effect of salts onprotein interactions,Phys.Rev.E53(1996)6325–6335. w15x M.Muschol,F.Rosenberger,Liquid–liquid phase sep-aration in supersaturated lysozyme solutions and asso-ciated precipitate formation y crystallization,J.Chem.Phys.107(1997)1953–1962.w16x C.Domb,J.H.Lebowitz,Phase Separation and Critical Phenomena,Academic,London,1983.w17x D.F.Rosenbaum,A.Kulkarni,S.Ramakrishnan,C.F.Zukoski,Protein interactions and phase behavior:sen-sitivity to the form of the pair potential,J.Chem.Phys.111(1999)9882–9890.w18x O.Galkin,P.G.Vekilov,Nucleation of protein crystals: critical nuclei,phase behavior and control pathways,J.Cryst.Growth232(2001)63–76.w19x P.R.tenWolde, D.Frenkel,Enhancement of protein crystal nucleation by critical density fluctuations,Sci-ence277(1997)1975–1978.w20x P.A.Darcy,J.M.Wiencek,Estimating lysozyme crystal-lization growth rates and solubility from isothermalmicrocalorimetry,Acta Cryst.D54(1998)1387–1394.112J.Lu et al./Biophysical Chemistry109(2004)105–112w21x A.J.Sophianopoulos,C.K.Rhodes,D.N.Holcomb,K.E.vanHolde,Physical studies of lysozyme.I.Characteri-zation,J.Biol.Chem.237(1962)1107–1112.w22x Y.Georgalis,P.Umbach, A.Zielenkiewicz,et al., Microcalorimetric and small-angle light scattering stud-ies on nucleating lysozyme solutions,J.Am.Chem.Soc.119(1997)11959–11965.w23x P.A.Darcy,J.M.Wiencek,Identifying nucleation tem-peratures for lysozyme via differential scanning calorim-etry,J.Cryst.Growth196(1999)243–249.w24x M.L.Grant,Effects of thermodynamics nonideality in protein crystal growth,J.Cryst.Growth209(2000)130–137.w25x J.J.Grigsby,H.W.Blanch,J.M.Prausnitz,Cloud-point temperatures for lysozyme in electrolyte solutions:effectof salt type,salt concentration and pH,Biophys.Chem.91(2001)231–243.w26x D.Voet,J.Voet,Biochemistry,Wiley,New Y ork,1990. w27x K.D.Collins,Charge density-dependent strength of hydration and biological structure,Biophys.J.72(1997)65–76.w28x R.Sousa,Use of glycerol and other protein structure stabilizing agents in protein crystallization,Acta Cryst.D51(1995)271–277.w29x M.Farnum, C.F.Zukoski,Effect of glycerol on the interactions and solubility of bovine pancreatic trypsininhibitor,Biophys.J.76(1999)2716–2726.w30x A.Priev,A.Almagor,S.Yedgar,B.Gavish,Glycerol decreases the volume and compressibility of proteininterior,Biochemistry35(1996)2061–2066.w31x S.N.Timasheff,T.Arakawa,Mechanism of protein precipitation and stabilization by co-solvents,J.Cryst.Growth90(1988)39–46.w32x C.S.Miner,N.N.Dalton,Glycerol,Reinhold Publishing, New Y ork,1953.。

习题一1. The differential equation of a system shown below, try to establish the dynamic structure diagram of the system and determine the transfer function Y(s)/R(s),Y(s)/N 1(s), Y(s)/N 2(s).dt)t (dy dt )t (y d )t (x )t (n )t (x )t (x )t (x dt)t (dx )t (x )t (x )t (x )t (x )t (x )t (n )t (y )t (r )t (x +=-==-==+-=22524534523121110232. A Feedback control system has the structure shown in figure 2. Determine the K 1 and K 2 so that the unit step response y(t) has T p = and =2%.Figure 2the input signal of the system is t )t ()t (r +=1,the measured output response for t e .).t ()t (y 109090--+=.(1) Determine the system transfer function )s (R )s (Y . (2) 、(3)For a unit step input and a unit ramp input ,calculate the steady-state error respectively.4. A negative feedback system has a loop transfer function22)s (s K)s (GH +=. (1) Using the Routh-Hurwitz criterion, find the value of the gain K when the closed-loop system has two poles on the imaginary axis.(2) Find the value of the gain K when s=-3 and other roots of the characteristic equation. unity feedback system has a plant211)s ()s (K )s (G -+=(1)Sketch the root locus of the closed-loop system. (2)Determine the range of K for stability. (3)Find the gain K at the breakaway point.…amplitude frequency characteristic curve of minimum phase systems shown below, write out the system transfer function respectively.L(w)dBL(w)dB 07. A unity feedback control system has a plant)s)(s (s )s ()s (G 13012110+++=(1) Plot the Bode diagram of G(s).(2) Determine the phase margin PM and gain margin GM. (3) Plot the polar plot and Mark GM, PM on the this map.习题二1. A unity negative feedback control system has the plant)2()(K s s K s G +=(1) 。

中 文 摘 要高炉炼铁是铁矿石(烧结矿、球团、块矿)还原、软化熔融和渣铁分离获得液态金属铁的过程。

铁矿石软化熔融形成的软熔带和渣铁滴落带直接影响着高炉燃料消耗和冶炼效率。

高炉内铁矿石在软熔带和滴落带的性能与其形成的中间渣的物理性质有着必然联系。

但目前缺少主要组成体系为CaO-SiO2-Al2O3-MgO-FeO的中间渣物理性质数据,导致无法正确认识铁矿石软熔滴落现象。

因此,有必要针对CaO-SiO2-Al2O3-MgO-FeO的中间渣的物理性质进行探讨,为进一步深入研究铁矿石的软熔滴落行为提供理论基础。

本文研究了二元碱度为1.4,10 %FeO-CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3五元渣系,其中MgO含量为6 %~16 %,Al2O3含量为6 %~16 %。

通过测量炉渣的黏度,来分别观察MgO含量、Al2O3含量和MgO/Al2O3对炉渣黏度的影响。

通过对炉渣的稳定性温度、黏流活化能来判断不同含量的MgO和Al2O3对炉渣流动性以及冶金性能的影响。

而且利用XRD和红外线光谱检测手段深入探讨炉渣结构与黏度规律之间的关系。

通过运用FactSage中的Viscosity模块与Phase Diagram模块进行计算,与实验测定的炉渣黏度进行对比。

结果表明:在10 %FeO-CaO-SiO2-MgO-15 %Al2O3五元渣系中,MgO含量为12 %时,炉渣黏度达到最低;在10 %FeO-CaO-SiO2-10 %MgO-Al2O3五元渣系中Al2O3的含量为12 %时,炉渣黏度最低;当MgO/Al2O3在0.7~0.8之间,炉渣流动性较好,并且具有良好的冶金性能。

当MgO含量为10 %,Al2O3含量为10 %时,炉渣的活化能最小,炉渣性能最稳定;当Al2O3含量为15 %,MgO为12 %时,炉渣的活化能最小。

利用FactSage模拟计算出五元渣系的相图与黏度规律,发现FactSage对黏度的模拟计算与实测黏度规律大体相同;通过对炉渣相图的模拟计算发现:1773K下,Al2O3含量为6 %、8 %时,渣系中存在镁硅钙石相(Merwinite)。

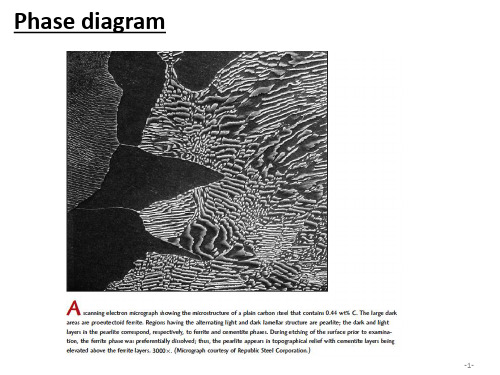

Phase diagramHello everybody, welcome to my class. Today, we will talk about phase diagram and Gibbs phase rule, as well as how to calculate the corresponding proportion of liquid phase and solid phase.译文:大家好,欢迎来到我的课程。

今天,我们将讨论相图,吉布斯相律,以及如何计算液相和固相的相对含量。

First of all, let’s introduce the definition of phase. Phase is defined as a homogeneous part or aggregation of material. This homogenous part is distinguished from another part due to difference in structure, composition, or both. The different structures form an interface to difference in structure and composition. (这里要注意相的概念,相是指在结构和组成方面与其它部分不同的均匀体。

)译文:我们首先学习相的定义。

相是指在一种材料中,结构、组成,或两者同时不同于其他部分的均匀体或聚集体部分。

不同部分间形成界面,也就是相与相之间的分界面。

Some solid materials have the capability of changing their crystal structure under the varying conditions of pressure and temperature, causing an ability of phase-change.译文:一些固体材料随着压力和温度条件的改变而发生结晶结构变化,具有相变的能力。