Paul Ehrlich

- 格式:doc

- 大小:100.50 KB

- 文档页数:5

第一句The environmentalists, inevitably, respond to such critics. The true enemies of science, argues Paul Ehrlich of Stanford University, a pioneer of environmental studies, are those who question the evidence supporting global warming, the depletion of the ozone layer and other consequences of industrial growth.词汇突破:1.environmentalist 环保主义者 2.Inevitably 不可避免的3.depletion of the ozone layer 臭氧层破坏(这属于是环保的标配词汇)4.consequences of industrial growth 工业增长的后果5.critics 批评6.pioneer 先驱7. question 质疑8. argue 认为The environmentalists, inevitably, respond to such critics. 环保主义者们不可避免地对这样的批评做出了回应。

第二句:主干识别: argues Paul Ehrlich of Stanford University, = Paul Ehrlich of Stanford University argues主谓充当的插入语:The true enemies of science are those其他成分:a pioneer of environmental studies, 同位语who question the evidence supporting global warming, the depletion of the ozone layer and other consequences of industrial growth. 定语从句翻译点拨:切分之后调整语序(按中文习惯)1.Paul Ehrlich of Stanford University (is)a pioneer of environmental studies,2.Paul Ehrlich of Stanford University argues斯坦福大学的Paul Ehrlich是环境研究方面的先驱,(这样诡异的不知道读音的人名在考场上一般就直接抄英文)他认为,或者翻译为:环境研究方面的先驱之一,斯坦福大学的Paul Ehrlich认为,3. The true enemies of science are those科学真正的敌人是这样一些人。

第二章肝脏疾病的检查项目及临床意义一、肝脏疾病实验室检查(一)肝脏实验室检查的临床意义1、筛选无症状肝病,判断有无肝损害2、辅助诊断各种类型肝病,评估肝病严重程度3、监测肝病进展,判断治疗效果和预后4、嗜肝病毒标志物、肝病自身抗体检查以判断病因(二)影响实验室因素1、在留取标本的过程中,受样本采集、贮运方法及是否溶血的影响2、在不同人种、个体之间存在性别、年龄、营养状况等多种影响因素(三)肝脏生化检查指标意义分述1 血清氨基转移酶:血清氨基转移酶主要包括丙氨酸氨基转移酶(ALT)和天门冬氨酸氨基转移酶(AST)。

ALT广泛存在于组织细胞内,以肝细胞含量最多,其次为心肌,脑和肾组织。

组织中ALT位于细胞质,其肝内浓度较血清高3000倍,是反映肝细胞损害的敏感指标。

AST主要分布于心肌,其次为肝脏、骨骼肌和肾脏等组织,存在于细胞质和线粒体,其中线粒体型AST活性占肝脏AST总活性80%左右。

心肌梗塞和慢性酒精性病等情况下AST升高以线粒体型为主,血清中AST/ALT比值升高。

正常人群血清ALT和AST浓度范围5~60 U/L,国际上将ALT检测上限(ULN)定为男性40 U/L,女性35 U/L;AST ULN为男性40U/L,女性34 U/L。

但有调查结果发现,约5%~10%的慢性乙型肝炎(CHB),15%慢性丙型肝炎(CHC)和非酒精性脂肪性肝炎(NASH)患者的血清氨基转移酶水平在“正常范围”内,因此认为目前的血清氨基转移酶ULN可能定义过高,已有专业学会提出降低ULN水平。

2008年美国专家委员会将ALT ULN定义为男性30 IU/L,女性19 IU/L;2009年欧洲肝病学会(EASL)将ALT ULN定义为男性31 IU/L,女性19 IU/L;2008年亚太专家共识建议ALT ULN不分性别,均定义为40 IU/L。

临床上氨基转移酶水平升高是指高于某临床实验室推荐的基线ULN水平,就专科而言,在制定抗病毒治疗方案时可以参考上述ULN指标。

诺贝尔奖与免疫学的百年渊源10月3日,瑞典卡洛琳医学院宣布:三位免疫学家布鲁斯·巴特勒(Bruce A. Beutler)、朱尔斯·霍夫曼(Jules A. Hoffmann)和拉尔夫·斯坦曼(Ralph M. Steinman),共同获得本年度诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

算上本届,近百年来免疫学研究获诺贝尔生理学或医学奖已经累计达到17次。

作为一个年轻的学科,免疫学能够屡获殊荣,这主要源于是其生命科学理论上取得的突破,以及在临床应用上获得的巨大成功。

理论上的突破19世纪,虽然人痘、牛痘可以预防天花,也出现了灭活疫苗(巴斯德的炭疽疫苗、狂犬疫苗),但是人们只能靠接种疫苗“主动免疫”,而对于机体免疫过程的发生原理却毫无认识。

1901年,首届诺贝尔生理或医学奖就授予了德国人贝林(Emil V on Behring),其发现了“抗毒素”,用动物血清治疗白喉患者取得巨大成功。

这也是免疫学上“被动免疫”和“血清疗法”的先河。

当初的“抗毒素”便是今天免疫学上“抗体”概念的雏形。

1908年,诺贝尔生理或医学奖授予德国科学家欧立希(Paul Ehrlich)和俄国科学家梅切尼科夫(Elie Metchnikoff),前者提出了抗体侧链形成的理论,认为抗体和抗原可以如同“钥匙和锁的匹配”,并且发现了补体的效应功能,因此被称为“体液免疫之父”;后者发现巨噬细胞和小噬细胞可以清除病原菌,提出创立了“细胞吞噬学说”,被誉为“细胞免疫之父”。

体液、细胞免疫学说的形成,也标志着免疫学科理论架构的形成。

此后,诺贝尔生理学或医学奖就格外钟情“免疫学”这个年轻学科,基本上免疫学范畴内每一个核心问题的阐释,每一次基础理论的突破,都在若干年后荣膺诺奖。

对于抗体的物质基础,美国科学家埃德尔曼、英国科学家波特研究发现,抗体是四肽组成的免疫球蛋白(1972年诺贝尔奖)。

对于抗体多样性的来源问题,从开始的“侧链形成理论”(1908年诺贝尔奖),发展到“克隆选择学说”(1960年诺贝尔奖),再到相对成熟的“天然选择学说”(1984年诺贝尔奖),最终通过杂交瘤技术(1984年诺贝尔奖)和抗体基因重排规律(1987年诺贝尔奖)得以证明。

Literary Onomastics StudiesVolume 2Article 71975What Happened to Sam-Kha in "The Epic of Gilgames?"John R. MaierFollow this and additional works at:/los****************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************,pleasecontact ********************.Recommended CitationMaier, John R. (1975) "What Happened to Sam-Kha in "The Epic of Gilgames?","Literary Onomastics Studies : Vol. 2, Article 7.Available at:/los/vol2/iss1/7What Happened to Sam-kha inThe Epic of Gilgame�?John R. MaierBefore a cave not far from the ancient Mesopotamian city of Uruk (Biblical Erech) rests an ancient poet and seer, grave in his turban and long beard, exiled, the poet says, 11By his own will from all the haunts of men.111 Heis a suitably dignified personage for an epic poem. His name is Heabani--Enkidu, we would say today. He belongs to the excitement caused when a brilliant British Museum scholar, George Smith, unearthed the cuneiform tablets of an epic poem now known as The Epic of Gilgame In spiteof his dignity, the seer Heabani is in a sense no longer with us. Gone is the turban; gone is the sage lover of Nature and Solitude: he belongs to a poem written in 1884 by a man, Leonidas Le Cenci Hamilton, who intended to complete the fragments translated earlier by George Smith, to make a poem that was both ancient and yet strikingly modern. Its name: Ishtar and Izdubar, The Epic of Babylon. Unlike the famous Rub of Omar Khy y am, the piece did not bring fame to the scholar-poet who labored so long to bring itMaier 2forth, and it inspired no cults. A hundred ye a rs of Gilgame� scholarship has passed it by. Today it is important mostly as a Nineteenth Century literary work reflecting an 1800s image of the Ancient Near East.My interest in this paper is in certain names appearing in one short but important early section of Hamilton's poem. The section is from the third of twelve tablets comprising the epic. For the most part I will mention only those names which subsequent scholarship on theGilgame� has found to be incorrect--almost ridiculous, some might say. But these names will serve as an introduction to the problems of translating names in ancient texts, and also as an indication of the way names deeply effect a narrative line and the concept of character in a1 i t erary work.A few preliminary remarks are necessary. The language of the original epic is Akkadian, an ancient Semitic language. The Akkadian epic of Gilgame�--a version of which goes back to about 1800 B.C.--in turn draws upon the Sumerian Gilgame� stories. (Sumerian is a language unre-Maier 3lated to Akkadian but a language that influenced nearlyall others in the Ancient Near East.) Hamilton, by the way, could not have known Sumerian or the influence oftexts older than the Akkadian version.2The Epic of Gilgame is complex. Here we are interested in only one part: how a creature, Heabani, i s seducedby a person called Sam-kha and makes his way thence to the city of Erech (Uruk) to meet the hero of the poem, Gilgame�, or as Hamilton called him, Izdubar. Doubtless the most moving part of the Gilgame� story is the grief of the heroat the loss of this friend Heabani, and the hero's subsequent search through the universe to find the answer to the problem of death. But the section w e are interestedin deals with .a very fascinating early stage of the story, just before the friendship between the hero and Heabani develops.Though modern scholars disagree about the interpretation of the events in the section (today it is Tablet Iof the epic),3 the events themselves are these. The people of Erech need someone to equal their restless king; inMaier 4response to their prayer, Heabani (Enkidu) is formed from clay and thrown into the wilds where the creature grows up with wild animals. The seduction by the or sacred prostitute, brings Heabani to manhood. Having become a man, he then abandons the wilds and enters the city, to meet the greatest of men, Izdubar (or Gilgame�).So at least goes the story as it is known today, made rather sure by a hundred years of intense research and translation. Hamilton's 1884 version of the events is abit different.The incredible change in the characterization of the wild man, Enkidu, provides a remarkable example of translation problems involving names that have tantalized the student of th� Gilgame� poem for nearly a century. For convenience I have chosen a few lines of the text that illustrate the problems, lines that have the advantage of being "nearly perfect11 in the original, according to George Smith. The same lines in R. Campbell Thompson's transcription and translation show the modern concept ofthe wild man, which he calls "Enkidu11 (see Appendix forMaier 5text, transliteration and translation).Enkidu has just been seduced by a prostitute in the service of the go d dess, I�tar. A savage being with no traces of human behavior, Enkidu is won over to humanityby the prostitute; for 11Six days and seven nights" she sleeps with the wild creature. At the end he has becomea man. The prostitute then initiates Enkidu into thearts and ways of civilization. In this passage the prostitute is encouraging Enkidu to go to the glorious cityof Erech, which has been oppressed by the mighty king, Gilgame�. Enkidu's response, in true epic fashion, is to boast of her might. The passage anticipates the furious battle to follow, when Gilgame� and Enkidu will wrestle-and then suddenly become friends. The heroes will then go off together to a series of great epic adventures.Imagine the astonishment, then, at taking up George Smith's translation of 1876 and the fuller account by Leonidas Hamilton (1884)!4 The character here is called11Heabani,11 not 11Enkidu.11 There is really little to dispute there, though. The modern reading is Sumerian. Hamilton'sMaier 6 11Heabani" is a rendering of the same cuneiform signs inAkkadian. The older suggestion was that the name meant the go d 11Hea11 (moder n 11Ea11) 11begot" or 11Created11 X--a s i n a name like Assurbanipal. "Enkidu,11 similarly',could carry the same meaning in Sumerian, the Sumerian god "Enki" being the equivalent of the Akkadian "(H)Ea."5The so-called temple 11Ellitardusi11 i.n dicates a second, but related, problem in dealing with Akkadian names. Campbell Thompson reads two words, i m qud-du-11holy (and) sacred,11 adjectives describing the dwelling of god Anu and the goddess I�tar (Appendix, line 44). In this case 111im" and "li11 are possible for the same (IGI) sign. 11Qud" is a reading of a sign that could be 11tar; tara; �ar;tir; t{r; kud/t; qud/t; has/s({,/z; �il or sil. "6 Notice . �·.that the texts do not indicate a break between the words in 1 i n e 44.These are typical problems. In a sense they are very minor ones, especially because they do not seriously effect the meaning of the passage or the work as a whole.But Hamilton's handling of 11Sam-kha" (mentioned in the89Maier 7sixth line of his version) and the "middannu" beast are serious indeed. The astonishing transformation of 11Heabani" can be seen in these two names.11Sam-kha," as Hamilton takes her, is both a person (she is Smith's 11Samhat") and "sweet Joy11 mentioned in the fourth line. Another woman--the one with the flashingeyes "half languid" is called Kharimtu. Kharimtu•s description of the "giant" Izdubar has persuaded somewhat the seer to meet the giant. But what really excites the wild man to go to Erech is not to match his strength againstI zdubar. (In fact, he does not fight the great king of Erech, in Hamilton's version.) What excites him is the delicious woman, "Sam-kha." The allegorizing tendency--as her name means '�J oy"--does not fully develop. But the distinction between 11Kharimtu" (or "Seduction11) and "Sam-kha" (11J oy") is based on a misconception that has very serious consequences. The two names actually describe one person-and neither is a proper name. Both refer to the prostitute sent to seduce the wild man. The confusion comes when thenames are written together, without any sign of punctuationMaier 8or coordination, as an epithet of the prostitute, One odd consequence is that Hamilton knew whatwas happening to Kharimtu as he read George Smith•s ver-sion, but Smith's version did not mention Samhat at the point where the women had been brought before Heabani•s11cave." Hamilton solves the problem by asking a question, in his usual florid way:But where hath Joy, sweet Sam-kha, roving gone?When they arrived at setting of the sunShe disappeared within with waving arms;With bright locks flowing she displayed her charms.As some sweet zir-ru did young Sam-kha seem,A thing of beauty Of some mystic dream.(III.III.48-53)Well, where did she go? Into a mystic whilethe other girl waited? According to Hamilton, Sam-khaenters the 11C ave11 where the turbaned seer, a hermit choice, it should be recalled, lives. The lines which describe the sexual encounter between the wild man and the prostitute are very graphic and possibly reach as close to our idea of pornography as Akkadian literature approaches, it seems. The Victorian scholar, George Smith, knew what to do: he simply deleted twenty-two lines of "directions11Maier 9 which he disguises in an innocuous comment buried at the end of his chapter: 11! have omitted some of the detailsin columns III. and IV. because they were on the one side obscure, and on the other hand appeared hardly adapted for genera 1reading.'' The Reverend A. H. Sayee, who revised Smith's book, deciding that even such an innocuous a comment as that was unnecessary, silently dropped even that.7So Hamilton faced the problem of the seduction by in-venting a scene that is delightfully vague.Her glorious arms she opens, flees away,While he doth follow the enticer gay.He seizes, kisses, takes away her breath,And she falls to the ground--perhaps in deathHe thinks, and o•er her leans where she now lay;At last she breathes, and springs, and flees away.But he the sport enjoys, and her pursues.(III.IV.21-27)Thus "sweet Joy" prompts him. Smith knew nothing of any great love of the wild man for this girl (developed in this scene). The only love which he shows again and again is the wild man•s love for Izdubar. The curious line in Smith, 11I join to Samhat my companionship,11 (line 42) isas far as Smith would go For Hamilton, though, a romanticMaier 10affair was a must for an ancient epic. He invents a love interest for Izdubar, a girl, Mua, and even beyond thatthe love interest between Izdubar and the goddess Ishtar. The separation of "Samkha11 and "Harimtu11 becomes the chief motivation for Heabani's entry into Erech.More curious than Sam-kha is the best called mid-dan-nu. The hunt for the "midannu11 beast is one of the fas-cinating chapters in early Assyriology. Smith thought it was a tiger. Sayee added more information, calling it a "fierce carnivorous animal allied to the lion and leopard;'' the 11midannu he found associated with the dumamu or cat.8A famous Khorsabad sculpture showing a hero holding a lion, was taken to be Izdubar strangling the midannu. Hamilton even took the,beast to be a pet of Heabani! usepet, which guarded the cave of Heaban, terri es a in 11Prince Zaidu,11 who had been sent by Izdubar to persuade Heabani to come to Erech, the king had had to send the two girls to seduce the hermit. Notice that (1) Heabani will take his pet to Erech in order to test Izdubar's strength; and (2) he will interpret a dream if Izdubar destroys theMaier 11 beast. In column V Hamilton does indeed describe thefight between the Herakles-figure, Izdubar, and the lion; Heabani then agrees to interpret the puzzling dream forthe king.What is astonishing about this is that no midannu beast existed--at least in this epic. A glance at Campbell Thompson•s text and transliteration will reveal the reason. The first line of column 5, the boast of Enkidu, includes the emphatic (and rather unusual) form of the first person pronoun: 111, too, am mighty!"--anaku-mi together with the ordinary Akkadian word for strength, dannu. Smith, with a corrupt text, had read across anaku-mi to mi-dan-nu. Once that was done, the beast is described as begotten "in desert11 with g�eat strength. It was but a short s to the idea that the beast would contest Izdubar, and the11prize11 would an interpretation of his dream.Hamilton's Heabani is, we see, not a primitive. sav�ge after all. A famous "barb" and seer, Heabani had lived inErech, had sung of the defeat of the city the hands of the Elamites, and had sung of Izdubar•s victory over the94Maier 12Elamites thereafter--this long before the episode we have been considering. But the seer had retired to his solitary cave. Indeed, Hamilton invents an "ode to solitude11in the manner of Coleridge for Heabani to sing when the seer discovers (through a divine revelation) he must go to Erech (Tablet II, column VI). Even Sam-kha•s seduction of him had been foreseen by this more than 11natural man.11With his turban and long beard, the seer Heabani was the archetypal poet-seer.Needless to say, perhaps, the concept of Heabani as a poet, as a seer, as the interpreter of dreams, has since been exploded. There was support for it in fragmentary texts, it seemed, but the laborious task of joining frag-ments of tablets� of establishing the sequence led to a creature fashioned by the godstab 1e ts, Gil g ame�.Campbell Thompson's translation shows the modern concept. The wild man describes, not his pet midannu but himself in the passage. Hardly a seer, Enkidu is entirely ignorant of mankind until the prostitute initiates him. Indeed, this passage is the first one in which Enkidu shows the human95Maier 13 capability of intelligible speech.Thus a misplaced sign sequence and a· split of one common name into two proper names has produced the midannubeast and Sam-kha. Both in turn develop the image of the poet seer, sensitive, a mystic and a loner, with a romantic's feeling for Nature and Love. What happened to Samkha? In her disappearance The Epic of Gilgame lost afirst�rate pre-Raphaelite love interest--and a poet.John R. MaierState University of New YorkCollege at BrockportNoteslLeonidas Le Cenci Hamilton, Ishtar and Izdubar, Theof Babylon (London: W .H. A 11 e n, Tab 1 e t I,Column IV, line 3.962on the Sumerian sources of The �ic of Gilgame see Paul Garell i , ed., Gi 1 g ame �et g_ l "\Paris:Imprimerie Nationale, 39-7. 3The earliest complete text of the epic is Paul Haupt, Das Babylonische Nimrodepos (Leipzig, 1884-1890), which Hamilton had seen. The standard text today is still R : Campbell Thompson, The Epi of Gilgame Text, Transllteration and Notes (London, 19294George Smith, The Chaldean Account of Genesis(London, 1876), pp. -S An 'Ay ('Ayya-Is-MY-Cre a tor ) is attested in Old Akkadian Sargonic Period )by J.J.M. Roberts, The Earliest Semitic Pantheon (Baltimore, 1972), pp. l g:-6; see also the ban art1cle in Chicago Assyrian Dictionary, vol. 2, pp. 81-95. 6Rykle Borger, Akkadische Zeichenliste (NeukirchenVluyn, 1971), p. 78 7smith,p. 205; George Smith, The Chaldean Account of Genesis, ed. , rev. , corrected A. H. Sayee ,p. 2Hamilton used Sayee's i on. B smith, pp. 205-206; Sayee, p. 4.AppendixLeonidas La Cenci Hamilton, ISHTARTHE IC OF BABYLON (1884) Tablet III, Column IV:IZDUBAR,Her flashing eyes half 1 d pierce seer, Until his first resolves a disappear�And rising to his feet his eyes he Toward sweet Joy, whose love for him And eyeing both with beaming sai 11With Sam-kha•s love the seer hath pl faith; And I will go to Elli-tar-d u-si, Great Anu's �eat and Ishtar's where wi thee, I will behold the giant Izdubar, Whose fame is known to me as king of war; And I will meet him there, and test power Of him whose fame above aii men .tower.A mid-dan-nu to Erech I will ke, To see -rfhe its mighty strength can break. In those wild caves i strength mighty If he the beast , I will make known His dream h all97Paul H IS NI , I, IV & VR.Ca mp be ll, THE EPIC}:;!" f:}f\ I, I . � 4-C ..-;:ru 1E! � Tf &>-�r v .q--:-�f31r Tf �T �nrr t:�r ��-�0-�;-;:if 4-s Tf � M-r-t:-r xr:s-:f-f::r JbT �;t':-r-. � �rr ff"'n <-w.. Tf rt�T �y-�rr � .. � .... �-�: ... � ...George Smith, THE CHALDEAN ACCOUNT OF GENESIS (1876) Tablet I II, Column IV:39. She spake to him and before her speech, 45 .40. the wisdom of his heart flew away and disappeared. 41. Heabani to her also said to Harimtu: 42. I join to Samhat my companionship, 43. to the templs of Elli-tardusi the of Anu I shtar, 44. the dwelling of Izdubar the mii 45. who also like a bull towers over 46. I will meet him and see his power,1. I2.3. In Column V:R. 11 Thompson, � I·;:r11'{ i'1--'fff ,_ �1rr�:�11 �·lt. F-�,c!f �"f r J:.r . �rIC ait s [1 , I, V 98R. Campbell Thompson, THE EPIC OF GILGAMISH [1929]Tablet I, Column IV40. i-ta-rna-as-sum-ma ma-gir ka-ba-sa41. mu-du-u lib-ba-su i-se-'-a ib-ra42. il UEN.KI.DU a-na sa-si-ma izakkara(ra) s al ha-rim-t43. -ki sal sam-hat ki-ri-en-ni ia-a-si44. a-na bi el-lim k du-si mu-sab il m il s-tar45. a-sar ilu Gilgamis git-ma-lu e-mu-ki46. u -i rimi ug-da-as-sa-ru eli nise P147. a-na-ku lu-uk-ri-sum-ma da-an-n[is 1] [bi-ma]Tablet I, Column V1. [lu-us]-ri-ih ina lib Uruk ki a-na-ku-mi dan-nu2. [a-na-ku]-um-ma si-ma-tu u-nak-kar3. [sa i-n]a seri 1--du [da-a]n i-mu�ki-suR. Campbell Thompson, THE IC OF LGAMISH [lTablet I, Column IV40. Her counselE'en as spake it found favour, cons ous he was45. Tabl of his longingSome c�mpanion so II Up' ' 0 giin meMe, to1 sh is'I' Co lumn Vi n o'er men li anL I' I 11 summon m, len dl y ( ng throughII , too,al ruly),(is am mighty! 11 NayI s0 is! )I '(I) ' will (e'en)in whoseny。

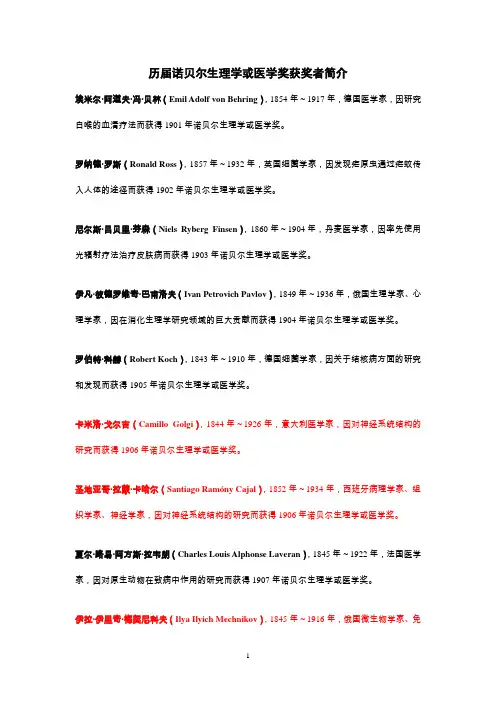

历届诺贝尔生理学或医学奖获奖者简介埃米尔〃阿道夫〃冯〃贝林(Emil Adolf von Behring),1854年~1917年,德国医学家,因研究白喉的血清疗法而获得1901年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

罗纳德〃罗斯(Ronald Ross),1857年~1932年,英国细菌学家,因发现疟原虫通过疟蚊传入人体的途径而获得1902年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

尼尔斯〃吕贝里〃芬森(Niels Ryberg Finsen),1860年~1904年,丹麦医学家,因率先使用光辐射疗法治疗皮肤病而获得1903年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

伊凡〃彼德罗维奇〃巴甫洛夫(Ivan Petrovich Pavlov),1849年~1936年,俄国生理学家、心理学家,因在消化生理学研究领域的巨大贡献而获得1904年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

罗伯特〃科赫(Robert Koch),1843年~1910年,德国细菌学家,因关于结核病方面的研究和发现而获得1905年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

卡米洛〃戈尔吉(Camillo Golgi),1844年~1926年,意大利医学家,因对神经系统结构的研究而获得1906年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

圣地亚哥〃拉蒙〃卡哈尔(Santiago Ramóny Cajal),1852年~1934年,西班牙病理学家、组织学家、神经学家,因对神经系统结构的研究而获得1906年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

夏尔〃路易〃阿方斯〃拉韦朗(Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran),1845年~1922年,法国医学家,因对原生动物在致病中作用的研究而获得1907年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

伊拉〃伊里奇〃梅契尼科夫(Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov),1845年~1916年,俄国微生物学家、免疫学家,因对免疫性的研究而获得1908年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

保罗〃埃尔利希(Paul Ehrlich),1854年~1915年,德国细菌学家、免疫学家,因发明“606”药品而获得1908年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

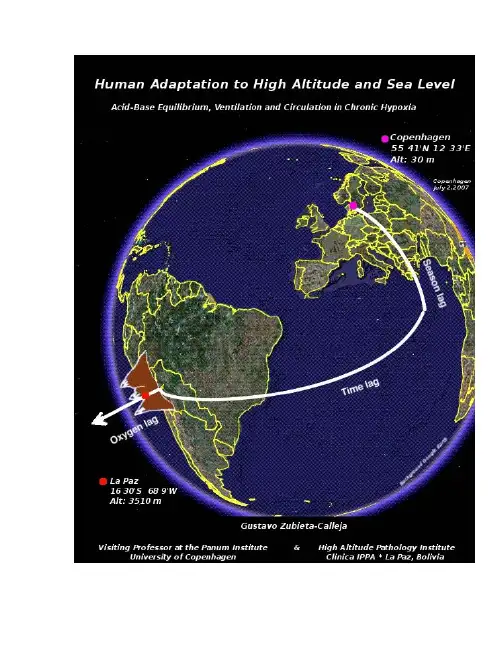

HUMAN ADAPTATION TO HIGH ALTITUDEAND TO SEA LEVELACID-BASE EQUILIBRIUM, VENTILATION AND CIRCULATIONIN CHRONIC HYPOXIAGustavo Zubieta-Calleja, MDHigh Altitude Pathology InstituteClinica IPPALa Paz,Bolivia Visiting Professor at the Panum Institute Faculty of Health SciencesUniversity of CopenhagenDenmarkE-mail: gzubietajr@Copenhagen, July 1st, 2007CONTENTSINTRODUCTION (7)CHAPTER A (11)ACID-BASE DISORDERS AT HIGH ALTITUDE (11)Normal values of blood gases at different altitudes (11)Arterial acid-base distribution curves at high altitude (11)Correction factors in {A} (15)CHAPTER B (18)SPORTS AT HIGH ALTITUDE (18)High altitude diving depths (18)Exercise at high altitude (19)Football at high altitude (21)CHAPTER C (23)BREATH-HOLDING AND CIRCULATION TIME AT HIGH ALTITUDE (23)Breath-holding at high altitude (23)Voluntary hyperventilation and breath-holding at high altitude (24)Defining circulation in relation to gravity (25)CHAPTER D (28)HYPO- AND HYPERVENTILATION AT HIGH ALTITUDE (28)Hypoventilation in CMS: an energy saving mechanism (28)Relativity applied to hyperventilation at high altitude (28)The increase of p a o2 through deep inspirations (30)The RQ is often different from R (30)CHAPTER E (33)CHRONIC MOUNTAIN SICKNESS (33)High altitude hematological terminology (33)The inadequate use of term “excessive polycythemia” (34)Low oxyhemoglobin saturation in CMS patients during exercise (35)Pulse oximetry in CMS (37)CHAPTER F (38)ADAPTATION TO HIGH ALTITUDE AND SEA LEVEL (38)Adaptation versus acclimatization (39)Effects of high altitude acclimatization (40)The increase in hematocrit during high altitude adaptation (40)High altitude residents suffer acute sea level sickness (43)Effects of low Altitude acclimatization (for highlanders) (44)Bloodletting (45)Bloodletting for space travel (46)Hypoxic environment in the space vehicles (47)CONCLUSIONS (48)CONCLUSIONS / SUMMARY in Danish (51)SYMBOLS AND UNITS (54)REFERENCES (58)To my beloved wife, Lucrecia De Urioste Limariño,for her kind and loving support during all these years ofresearch in Copenhagenand to my two daughters Natalia and Rafaela, for their interest, stimulus and with whom we enjoy so muchthe “ride in the train of life”.ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSI am most grateful to:Gustavo Zubieta-Castillo (Sr), Poul-Erik Paulev, Luis Zubieta-Calleja, Nancy Zubieta-Calleja, Rosayda de Bersatti, Clotilde Calleja, Ole Siggaard-Andersen, Kirsten McCord, Kirsten Paulev, Carsten Lundby, Jørgen Warberg, Kristian Karlsen, Martiniano Vicente, High Altitude Pathology Institute, Instituto Geografico Militar, Armada Boliviana, Ejercito de Bolivia, University of Copenhagen, The Copenhagen University Library, and the Danish Society.INTRODUCTIONTwenty three years of medical practice and research at high altitude in the city of La Paz evolved into a dilemma upon arriving to Copenhagen four years ago. The author’s wife was sent on mission to the Bolivian Embassy and he had contacted Dr. Poul-Erik Paulev at the Panum Institute of Medical Physiology of the University of Copenhagen. The experience with high altitude medicine and physiology appeared of limited use in a country where the highest point is at 170 meters above sea level. Nevertheless, Dr Paulev showed keen interest in scientific collaboration, immediately upon arrival. We began to work jointly on a paper called “Essentials in the diagnosis of acid-base disorders and its high altitude application”. The first section is dedicated to a review and analysis of the historical and transcendental development in Acid-Base physiology born fundamentally here in Copenhagen. The second part is an application of the nomogram developed by Ole Siggaard-Andersen to high altitude, a subject thus far overlooked and important in intensive care life saving therapy. Scientific collaboration further extended to the Glostrup hospital with adaptation studies of the retina with Michael Larsen and football (soccer) at altitude matters at the August Krogh Institute with Jens Bangsbo.Close to 2 million people live in the city of La Paz, Bolivia, a modern bowl-shaped city, with altitudes ranging from 3100 m to 4100 m above sea level in the heart of the Andes. The airport, located at 4000 m, is enveloped by close to 600,000 inhabitants. The local mean barometric pressure at IPPA, our laboratory, is around 490 Torr (65% that of sea level). The partial pressure of oxygen molecules in the inspired air = 94 Torr is 1/3 less than at sea level. Similarly, the mean arterial partial pressure of oxygen = 60 Torr (7.99kPa) and of carbon dioxide = 30 Torr (3.99 kPa) are 1/3 and 1/4 less, respectively.Given the difficulty of attaining reliable data on altitude related pathologies, Dr. Gustavo Zubieta Castillo (Senior), a highly trained and experienced Bolivian physician, specialized in the field of cardio-respiratory physiology, created in 1970 "Clinica IPPA: del Instituto de Patologia de la Altura", an internationally prestigious medical Institute specialized in high altitude medicine. The author has worked in thisinstitution during 26 years as a medical doctor, research scientist, pulmonologist and professor.Travelers arriving to high altitude from sea level can present acute mountain sickness (AMS) and occasionally High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) or High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE). IPPA also functions as a clinic attending local residents - whose medical test results and clinical problems differ from those at sea level. Residents with chronic pulmonary disease and those with sequelae from previous lung disease frequently suffer from Chronic Mountain Sickness. Most of the equipment and software is developed in the same Institute by the author, making the Institute highly sophisticated with on-line data acquisition. The equipment can be modified in short term, involving software or hardware setup, in order to carry out research.Until now, medicine in the Bolivian Andean region (and in many mountain areas of the world) is practiced according to sea level standards. Most physicians return from sea-level training, applying their up-to-date knowledge to high altitude residents encountering varied problems in doing so. At the same time, few scientific expeditions from abroad arrive, making only short period observations in basic physiology mostly applied to acute changes due to mountain ascent. However, the problems of permanent residents and the changes they suffer on descent to sea level are broadly overlooked. The “abundance” of oxygen at sea level is taken as a favorable event. For example, difficulties encountered by high altitude soccer players switching to high oxygen pressures at sea level, are disregarded and poorly understood. The complete adaptation times of both changes of altitude (going up or down) are important. A new system to measure full hematological adaptation is required and here presented. A formula of hematological adaptation or acclimatization periods is created giving numeric values to be used when going to any fixed altitude.The collaboration with Dr. Paulev has given rise to joint publications where high altitude data previously acquired over many years was analyzed applying Danish knowledge and experience in physiology. The following hypotheses were formulated:A. Are sea level acid-base charts suitable for diagnosis of disorders and theirtreatment at high altitude?B. Is it possible to improve the high altitude diving tables?8C. Is there a difference in circulation time between patients with chronicmountain sickness and normal residents at high altitude?D. Do Chronic Mountain Sickness (CMS) patients save energy by decreasingventilation and increasing the number of red cells, thereby achieving the most energy efficient mechanism of oxygen transport in order to sustain life?E. Can CMS be defined as polyerythrocythemia due to a broad spectrum ofmedical conditions?F. What is the explanation for acute, sub-acute and chronic mountains sickness athigh altitude? What are the physiologic changes of high altitude residents and temporary visitors to high altitude, upon return to sea level?The following are the peer reviewed and published papers that answer these questions;A. “ESSENTIALS IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF ACID-BASE DISORDERS ANDTHEIR HIGH ALTITUDE APPLICATION”.P.E. PAULEV, G.R. ZUBIETA-CALLEJA.JOURNAL OF PHYSIOLOGY AND PHARMACOLOGY 2005, 56, Supp 4, 155-170.B. “HIGH ALTITUDE DIVING DEPTHS”. P.E. PAULEV and G.R. ZUBIETA-CALLEJA.RESEARCH IN SPORTS MEDICINE. Volume 15, Issue 3 July 2007 , pages 213 – 223.C. “NON-INVASIVE MEASUREMENT OF CIRCULATION TIME USINGPULSE OXIMETRY DURING BREATH HOLDING IN CHRONICHYPOXIA”. G.R. ZUBIETA-CALLEJA, G. ZUBIETA-CASTILLO, P-E. PAULEV, L. ZUBIETA-CALLEJA. JOURNAL OF PHYSIOLOGY AND PHARMACOLOGY 2005, 56, Supp 4, 251-256.D. “HYPOVENTILATION IN CHRONIC MOUNTAIN SICKNESS: AMECHANISM TO PRESERVE ENERGY”.G.R. ZUBIETA-CALLEJA, P-E. PAULEV, L.ZUBIETA-CALLEJA, N. ZUBIETA-CALLEJA, G. ZUBIETA-CASTILLO.JOURNAL OF PHYSIOLOGY ANDPHARMACOLOGY 2006, 57, Supp 4, 425-430.E. “CHRONIC MOUNTAIN SICKNESS: THE REACTION OF PHYSICALDISORDERS TO CHRONIC HYPOXIA”.G. ZUBIETA-CASTILLO Sr, G.R. ZUBIETA-CALLEJA Jr, L. ZUBIETA-CALLEJA .JOURNAL OF PHYSIOLOGY AND PHARMACOLOGY 2006, 57, Supp 4,431-442.9F. “ALTITUDE ADAPTATION THROUGH HEMATOCRIT CHANGES”.G.R.ZUBIETA-CALLEJA, P-E. PAULEV, L. ZUBIETA-CALLEJA, & G. ZUBIETA-CASTILLO. JOURNAL OFPHYSIOLOGY AND PHARMACOLOGY 2007, 58, Suppl 5, 811.818Please note that reference within the following pages to these articles are enclosed in bold letters and brackets as in {A}. T his dissertation is by no means a review of all the scientific literature of every detail presented here, although in some areas there is comparison. The reason is that the material, herein presented, is quite extensive and a resume of original observations of over 36 years at the High Altitude Pathology Institute that has led to the current work at the University of Copenhagen. CMS is only touched briefly and is subject of discussion in other publications [1-6].1011CHAPTER AACID-BASE DISORDERS AT HIGH ALTITUDENormal values of blood gases at different altitudesAs the barometric pressure exponentially decreases with incrementing altitude, the P a O 2 and P a CO 2 both decrease as shown in Table 1. These are normal values from our laboratory in La Paz and the three lower rows only come from a few samples drawn under difficult conditions during mountain climbing. This data is shown here for comparison only. The altitude of major importance for this work is at 3510 m in our laboratories in the city of La Paz, a bowl shaped city in the Andes, ranging between 3100 m up to 4100 m.ALTITUDEm PB Torr P a CO 2 Torr (kPa ) P a O 2 Torr (kPa ) Sea Level 760 40 (5.33) 100 (13.33) 3510 (La Paz)49530 (3.99)60 (7.99)6400 344 20.7 (2.76) 38.1 (5.08) 7440 300 15.8 (2.11) 33.7 (4.49) 7830 288 14.3 (1.91) 32.8 (4.37) 8848*253 7.5 (1.00)29.5 (3.90)Table 1. Normal values of blood gases for different altitudes. * The Everest values are calculated [7].Arterial acid-base distribution curves at high altitudeAt the High Altitude Pathology Institute - Clinica IPPA, located at 3510 m above sea level in the city of La Paz [8], a computerized database containing 2431 records of blood gas studies recollected over 10 years, was analyzed. These had been run on a pHmK2 Radiometer Acid-Base Analyzer, properly calibrated according to the company's specifications. These results show the variation of blood acid-base values and blood gases in a high altitude population that lives a normal life that include all activities of a metropolis in spite of the chronic hypoxia. After excluding all the tests performed using supplementary oxygen, a total of 1865 records that included both sexes, with a meanweight of 64.52 ± 17.21 (SD) kg and a mean hemoglobin concentration of 10.4 ± 2.17 mM (16.85 ± 3.45 g%) gave the following results. Note that this refers to data taken from a medical center in order to observe a distribution pattern of patients at high altitude and is not to be taken as normal values.pH P a CO 2 Torr (kPa )Pa O 2 Torr (kPa )Mean = 7.38 29.4 (3.91) 52.4 (6.98) S.D. =0.19 6.9 (0.91) 9.8 (1.30)Table 2. The mean and standard deviation of the arterial blood gases of the IPPA database of 1865 patients.Fig. 1. Frequency pH distribution of arterial blood of 1865 patients at high altitude 3510 m.The high kurtosis curve in Fig. 1, shows that most patients had a normal pH of 7.4. This is because many were suffering from disease that did not compromise the acid-12base status of blood. However, the incidence of a pH of 7.5 is also important since at high altitude hyperventilation is one of the fundamental compensation mechanisms for acute hypoxia. Metabolic (or rarely respiratory) acidosis is present and a result of disease that is of the same characteristics as at sea level.Fig 2.P a O2 frequency distribution of 1865 patients examined at our laboratory in La Paz.The normal P a O2 is 60 Torr (7.99 kPa) in the capital of La Paz (Table 1). Fig. 2 shows a negatively skewed curve as the patients at high altitude with cardio-respiratory disease tend to have a decrease in the P a O2. On the far left there are some subjects that had a very low P a O2. These unusual cases led to further investigation and the description of the Triple Hypoxia Syndrome by Gustavo Zubieta-Castillo (Sr.) not detailed in this dissertation [9, 10]. These tolerance to low P a O2 values also led to the proposal of a new theory by Gustavo Zubieta-Castillo (Sr.) of human adaptation to the hypoxic levels of the summit of Mt. Everest [11, 12].13Fig 3. Distribution curve of the P a CO2 in 1865 patients including both sexes at 3510 m.Above 90 % of the patients have a P a CO2 below 40 Torr (5.33kPa) (Fig. 3). The average is at 29.4 as seen in Table 2, happens to be the same as the value of normal at 3510 shown on Table 2. This implies that although the average P a O2 can be lower at high altitude during disease, the average P a CO2 remains within the normal limits. It also shows that the highest values reached are around 57 and in some extreme but very isolated and serious cases up to 73 Torr (9.73kPa). At high altitude it is not possible to tolerate a high P a CO2.All medical centers in the world working above 2500 m of altitude are using sea level tables and nomograms to make acid-base corrections in critically ill patients. If the Siggaard-Andersen nomogram is observed in the city of La Paz (3510 m), where the normal P a CO2 = 30 Torr (3.99 kPa), the base deficit (currently renamed Titratable Hydrogen Ion Concentration) by its original author [13] and Titratable Hydrogen Ion concentration Difference from normal (THID) by us [14]) is found to be –5. However, the acid-base correction, is made to 0. A critically ill patient from diverse conditions,14such as post-operative, acute metabolic acidosis like in diabetes will be corrected to sea level values. This implies regulating the optimal cellular equilibrium to a different environment, where P a CO2 would be 40 Torr (5.33kPa) at a pH of 7.4. Clearly this is not the way to correct acid base disorders at any altitude as the Base Deficit increases exponentially with altitude following the barometric change (Fig. 4).Fig. 4. Shown here is the old Base deficit terminology and the actual high altitude values plotted against the barometric pressure with the current sea level Van Slyke formula. The equation corresponds to the best fit curve.In our report {A}, three tables are presented for different altitudes. These were developed based on the calculated value of P a CO2 at different altitudes and setting the 0 point of THID to these values. P a CO2 versus altitude was analyzed from data provided by different authors as explained in {A}.Correction factors in {A}The development of the corrected Van Slyke formula for high altitudes {A}, is herein developed and explained.15We initiate the application to high altitude by modifying the original Van Slyke formula.:THID = - 0.93 * ∆(HCO3-) + 14.6 * (pH-7.40) (1)where ∆ (HCO3-) = (actual bicarbonate) - 24.5 mM, for a hemoglobin concentration of 3 mM in eECF. This is due to the fact that the normal hemoglobin (at sea level) taken to be around 9.18 mM is divided by 3 as originally suggested by Ole Siggaard-Andersen, as he considers this to be the buffering capacity in the extended extra cellular fluid volume (eECF). Note that extended includes the extra-cellular fluid plus the red blood cell volume.The first constant factor 0.93 and the second constant factor 14.6 depend upon the hemoglobin concentration [15].The following formula shows the formula above (1) in detail:THID in eECF = (1 – ((Hb) / 43)) * (∆ (HCO3-) + βB * (pH-7.4)) (2)Where (Hb) = (Hb in mM)/3 in the eECF and∆ (HCO3-) = (actual HCO3-) - (Altitude HCO3-)(Altitude HCO3-) = -1.8 x (altitude in km) + 24.32 (3)The calculated mean altitude HCO3- values for the chosen altitudes (2500 m, 3500 m, and 4500 m) are 19.8, 18 and 16.2 mM, respectively. These go into the altitude formulas described below and shown in bold italic characters.The 43 factor above is an empirical constant accounting for plasma-erythrocyte bicarbonate distribution [15].Additionally the buffering capacity of a normally increased hemoglobin concentration at high altitude must be taken into account in order to be precise. The first term in the Van Slyke equation ((Hb) factor 1) is calculated based on the data from our aboratory: (Altitude Hb) = (Hb) + 0.2 * (altitude in km) (4) where (Hb) is the normal eECF sea level value of 3.16which results in 0.93, 0.92 and 0.91 at the three altitudes, respectively. The buffer valueof non-bicarbonate buffers in blood (βB) is calculated using these altitude Hbvalues and the formula:βB = 2.3 * (Hb) + 7.7 mM [15] (5) being 14.9, 15.1, and 16.7 mM at the 3 altitudes, respectively.Furthermore, one fundamental observation that is borne from this analysis is that the much lower bicarbonate buffer concentration at high altitude minimizes its buffer capacity, whereas the non-bicarbonate buffer capacity increases somewhat.These same calculations (equations 3 and 4 above) can be performed using the barometric pressure:(Altitude HCO3-) = 0.0256 x (PB in Torr) + 5.15 (6) (Altitude Hb) = (Hb) + (2.25 - 0.003 * (PB in Torr)). (7) Barometric pressure is taken into account, since most acid-base analyzers now have barometers included. Accordingly, the formulas for each level shown in the graphs in {A} are:At sea level:THID in eECF = -0.93 * (∆ (HCO3-) + 14.6 * ∆pH)where∆ (HCO3-) = (actual bicarbonate) - 24.5 mM.At 2500 m:THID in eECF = -0.93 * (∆ (HCO3-) + 14.9 * ∆pH)where ∆ (HCO3-) = (actual bicarbonate) - 19.8 mMAt 3500 m:THID in eECF = -0.92 * (∆ (HCO3-) + 15.1 * ∆pH)where ∆ (HCO3-) = (actual bicarbonate) - 18.0 mM.At 4500 m:THID in eECF = -0.91 * (∆ (HCO3-) + 16.7 * ∆pH)where ∆ (HCO3-) = (actual bicarbonate) - 16.2 mM.If the bicarbonate high altitude levels are used in the sea level equation, then the result will give a false THID. This is the reason for creating 3 tables for the altitudes (2000-2999, 3000-3999 and 4000-5000 m) in {A}.17CHAPTER B SPORTS AT HIGH ALTITUDEThe practice of sports at high altitude is a subject of growing interest worldwide. The practice of mountain climbing increases and brings forth further goals and challenges. The understanding of the physiology helps improve the quality and reduce the risks of these sports.High altitude diving depthsDiving at high altitude carries a higher risk as noted by Prof. Paulev upon a visit to the Bolivian Navy high altitude diving school, located on Lake Titicaca at 3600m. Several years back the US Navy visited the lake and brought along several divers, scientists and even pressure chambers. The deepest dive under controlled conditions was made to 15 meters. They developed tables with barometric corrections, but these were not complete and overlooked some aspects. We have introduced the Standard Equivalent Sea Depth (SESD) which allows conversion of the Actual Lake Diving Depth (ALDD) to an equivalent sea dive depth.SESD is defined as the sea depth in meters or feet for a standardized sea dive equivalent to a mountain lake dive at any altitude, such that:SESD = ALDD * [Nitrogen Ratio] * [Water density ratio]SESD = ALDD * [(760 – 47)/(P B - 47)] * [1000/1033]SESD = ALDD * [SESD factor]For this reason, it was found convenient to re-analyze the data following calculation of the SESD factor, we recommended the use of our diving table with 2 guidelines:1) The classical decompression stages (30,20, and 10 feet or 9,6, and 3 m)are corrected to the altitude lake level, dividing the stage depth by theSESD factor, including the water vapor pressure factor and thenitrogen ratio in {B}.182) The lake ascent rate during diving is equal to the Sea Ascent ratedivided by the SESD factor.The new diving table was presented at the 1st Symposium on the Effect of Chronic Hypoxia on Diseases at High Altitude. It is a contribution to safer diving at high altitude thereby reducing the risk of decompression sickness at the altitude of Lake Titicaca. The tables are now under evaluation at the naval diving school.Another study looked at the decompression sickness following seawater hunting using underwater scooters. (Hans Christian Møller Thorsen, Gustavo Zubieta-Calleja Jr. and Poul-Erik Paulev. In print at Research in Sports Medicine).Exercise at high altitudeThe metabolic carbon dioxide production divided by the simultaneous oxygen consumption equals the metabolic respiratory quotient (RQ) for all cells of the body. The ventilatory exchange ratio (R) equals the carbon dioxide elimination from the lungs divided by the simultaneous oxygen input.RQ equals R at respiratory steady state but otherwise not (see the section “The RQ is often different from R”).The accumulative sub-maximal work capacity of 17 male Aymara natives of La Paz, as evaluated and compared in three conditions: 1) La Paz (LP) 3510 m, PB = 495 Torr (66.0 kPa), PIO2 = 94 Torr (12.5 kPa). 2)Simulating Chacaltaya (SC) at the same altitude in the hyperoxic/hypoxic adaptation chamber with a PIO2 = 77 Torr (10.3 kPa) and 3) in the Chacaltaya Glass Pyramid Laboratory (CH), at 5200 m, PB = 398 Torr (53 kPa) and PIO2 = 74 Torr (9.8 kPa) [16],[17, 18]. ECG, V E, PEO2, P E CO2 and SaO2 (pulse oximetry) were measured on-line in a computerized system that calculated VO2, VCO2 and the ventilatory exchange ratio (R). The USAFM exercise treadmill protocol was utilized with 0/0, 2/0, 3/0, 3/5, 3/10, 4/10 (mph/Degrees) 3 minutes each stage. Expired air samples were taken near the end of each stage with automatic calibration software taking into account the barometric changes. Data analysis (mean ± SEM) at rest (standing on a treadmill) and at sub-maximal exercise was performed during the final minute of the 5th level of exercise (Table 3).19RestVO2 L/min VCO2 L/min R SaO2 % Pulse /min RLP 0.46 ± 0.12 0.50 ± 0.12 1.07 ± 0.14 90.4 ± 1.7 72.5 ± 6.0 SC 0.37 ± 0.20 0.51 ± 0.17 1.35 ± 0.31 84.4 ± 3.4 84.9 ± 13.7 CH 0.17 ± .08 0.22 ± .07 1.25 ± 0.15 82.1 ± 5.0 92.0 ± 11.4 Sub-maximal ExerciseE VO2 L/min VCO2 L/min R SaO2 % Pulse /min LP 3.76 ± 0.50 4.29 ± 0.71 1.14 ± 0.15 86.5 ± 1.8 142.3 ± 11.9 SC 3.16 ± 0.68 4.29 ± 0.53 1.35 ± 0.33 76.2 ± 3.3 151.2 ± 13.9 CH 1.37 ± 0.49 1.83 ± 0.27 1.33 ± 0.17 76.2 ± 6.1 152.4 ± 11.5 Table 3. Gas exchange, R, SaO2 and pulse as measured in 17 Aymara natives both at rest and at the end of a sub-maximal exercise.The Table 3 material is shown in detail graphically in Fig. 5 and Fig. 6.Fig 5. VO2 and VCO2 at rest and different stages of exercise in La Paz 3510 m. solid lines (shown here as IGM, which stands for Instituto Geografico Militar) and at Chacaltaya 5230 m in doted lines.20Fig. 6. Saturation, pulse and ventilation measured in La Paz (shown as IGM) and in Chacaltaya at rest and during the different stages of exercise (data From Table 6).The accumulative sub-maximal work capacity is essentially the same during the 3 different conditions at both altitudes in spite of a lower oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production at high altitude.Football at high altitudeTwo groups were tested for a football adventure. The Sajama Group (SG) were 7 healthy male Aymara natives (Age: 32.2 ± 5.7) born and living in the Sajama village at 4200 m at the base of the Sajama Mountain (6542 m), that work as guides and porters at the mountain Sajama and other high mountains in Bolivia. The La Paz group (LP) were 17 healthy Aymara male natives (Age: 21.3 ± 6.5) of the Bolivian army Instituto Geografico Militar (IGM), born and living in La Paz (3500 m), constantly in physical exercise. The USAFM exercise protocol described above was used once more.The SG maintains the SaO2 at rest and during the first 3 stages of exercise, and drops in the last two stages. In the LP group the SaO2 drops immediately at the start of exercise (Fig. 7).21Fig. 7. Comparison of the two groups Sajama (SG) and IGM normal residents both at La Paz (LP) during a sub-maximal treadmill exercise test..The SG ascended in 7 hours from the Sajama Village at 4200 m to the summit at 6542 m, prepared the soccer field, played 40 minutes intensely and returned to celebrate to the Sajama Village, all in 16 hours. This traduces a remarkable capacity to perform accumulative sub-maximal exercise at extreme altitudes. The football game played by the Bolivian Aymara on the summit of Mount Sajama at 6542 m in August 2nd, 2001, shows that even at that altitude, football is possible. One player vomited but continued to play. We have the video recording showing the game that lasted 20 minutes per side.Football (soccer) at high altitude is a subject of constant controversy in the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA). In 2001 they vetoed world cup games in the city of La Paz. There was a social outcry and a defense of the practice of sports at high altitude. Now in June, 2007, the FIFA once more has proposed the same veto. Immediately after, the President of Bolivia, Evo Morales played a soccer game at 6000 m on Mount Sajama to prove that it is possible without AMS and no cases were reported. The BBC reported both events (2001 and 2007). Highland football players going to sea level can suffer the effects of “relative hyperoxia lag” (Table 11).22.CHAPTER C BREATH-HOLDING AND CIRCULATION TIMEAT HIGH ALTITUDEBreath-holding at high altitudeBreath holding produces respiratory and cardiac changes well documented at sea level [19-21]. The great variations in the low pulse oximetry saturation in normal residents at La Paz were observed with a new breath-holding (BH) technique. A computer was set up to display on-line, ventilation by pneumotachograph, infra-red capnography, and pulse oximetry (finger probe). The seated subject using a nose-clip and breathing in steady state through a mouthpiece during 2.5 minutes (1 screen), was asked to hold his breath at total lung capacity (TLC) up to the breaking point (beyond no-respiratory sensation).A typical graph of the saturation response is plotted, where two peaks are shown, one after deep inspiration and the other following the compensatory hyperventilation, with a low saturation in-between (Fig. 8). In fourteen non-trained normal native males (mean age 28.2 ± 7.81 S.D.) the average breath-holding time (BHt) was 65.2 ± 20.08 S.D. seconds. The resting saturation (x = 90.4% ± 1.34) rose to a peak saturation (SATmax) x = 97.1% ± 1.29 (p<0.0001), similar to sea level values, following maximum inspiration prior to BH at x = 34.9 ± 9.93 seconds (maxSATt), an unexpected long blood transit time. In spite of individual variations, saturation decreased after BH to an average of 78.0% ± 5.70.The first deep inspiration followed by hyperventilation induced at breaking point gave a second peak of saturation at 36.4 ± 10.59 seconds with a correlation of r=0.93 with respect to maxSATt. The end-tidal CO2 (ETCO2) remained constant with resting respiration (x = 29.0 ± 1.53 Torr) (3.87 ± 0.20kPa) and increased to x = 33.6 ± 1.90 Torr (4.48 ± 0.25kPa) (BH- ETCO2) at breaking point expiration (p <0.0001). The correlation between BHt and BH- ETCO2 was r = 0.66.23。