How it Works: A Field Study of

Non-Technical Users Interacting with an Intelligent System

Joe Tullio

Applications Research Center Motorola Labs Schaumburg, IL 60196 jtullio@https://www.doczj.com/doc/e62320986.html, Anind K. Dey, Jason Chalecki ? Human Computer Interaction Institute Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA 15213 anind@https://www.doczj.com/doc/e62320986.html, James Fogarty Computer Science & Engineering

University of Washington Seattle, WA 98195 jfogarty@https://www.doczj.com/doc/e62320986.html,

ABSTRACT

In order to develop intelligent systems that attain the trust of their users, it is important to understand how users perceive such systems and develop those perceptions over time. We present an investigation into how users come to understand an intelligent system as they use it in their daily work. During a six-week field study, we interviewed eight office workers regarding the operation of a system that predicted their managers’ interruptibility, comparing their mental models to the actual system model. Our results show that by the end of the study, participants were able to discount some of their initial misconceptions about what information the system used for reasoning about interruptibility. However, the overarching structures of their mental models stayed relatively stable over the course of the study. Lastly, we found that participants were able to give lay descriptions attributing simple machine learning concepts to the system despite their lack of technical knowledge. Our findings suggest an appropriate level of feedback for user interfaces of intelligent systems, provide a baseline level of complexity for user understanding, and highlight the challenges of making users aware of sensed inputs for such systems.

Author Keywords

Intelligent systems, context-aware, mental models, qualitative research, machine learning, field study.

ACM Classification Keywords

H5.m. Information interfaces and presentation (e.g., HCI): Miscellaneous. I2.m. Artificial Intelligence: Miscellaneous.

INTRODUCTION

Intelligent systems continue to find their way into everyday applications. These systems gather information about their users, reason from what they have learned in the past, and generate predictions or decisions based on this reasoning. Examples include spam filtering applications and product recommenders. While these applications are quite useful, intelligent systems promise to do much more in terms of automating tasks and increasing awareness by inferring the states of users and environments. Such applications demand a higher degree of trust from users before they are willing to delegate important decisions or personal information to a software system [8, 17]. This trust comes from an ability to predict the system's behavior through observation [20]. To predict and explain the behavior of a system, people construct mental models that may be more or less complete and accurate [22]. Therefore, designers must create intelligent applications that enable the formation of mental models that are predictable enough to merit their trust [3]. This presents a difficult challenge, since designers may not know the degree to which non-technical users can understand concepts related to intelligent systems. In addition, they do not know how these mental models may change over time as users gain experience with the system.

In the interest of increasing designers’ knowledge of how users come to understand intelligent systems, we conducted a six-week field study intended to compare user mental models of an intelligent application with the actual system model. We designed, built, and deployed an application that employed user-trained sensor-based statistical models to provide estimates of worker interruptibility. These estimates were then displayed on screens mounted at their office doors. By interviewing the direct reports of managers who were using the application, as well as capturing in situ use through on-site surveys, we were able to document how their understanding of the system’s operation developed over time. In addition, we were able to ground their stated beliefs about the system with actual instances of use. Our findings show that even when some details of the system’s implementation were revealed, higher-level beliefs about how the system operated remained surprisingly robust, even when those beliefs were flawed and new or contradictory evidence was presented. However, lower-level beliefs about what the system was sensing in order to make its inferences changed substantially over the course of the study period, with participants able to discount some of their early misconceptions before the study’s conclusion.

? Jason Chalecki is now with Oracle Corporation.

In addition, we found that several of our participants gave lay descriptions attributing simple statistical or rule-based machine learning concepts to our application, despite having no technical knowledge of such systems. These results expose the important challenge of dealing with the inertia of static mental models in intelligent UI design, suggesting that users may need additional, high-level feedback in order to adopt more correct structures. We provide some guidance to this challenge by illustrating the various intelligent constructs participants ascribed to our system as a baseline of the complexity users can grasp in intelligent systems. Lastly, while our participants improved their notions of what our system was sensing through experience, simple feedback in the interface about such inputs may not be enough accelerate this improvement.

In this paper, we first discuss related work on mental models and the use of explanations for intelligent systems. We describe our six-week field study of an intelligent system, including the participants used, the technology implemented, and our data collection and analysis methods. We then present our results, showing how participants’ mental models varied across participants but remained stable over time. Finally, we discuss how our results can be used, both in terms of what level of understanding to expect from users and avenues that could mitigate incorrect or incomplete mental models.

RELATED WORK

In this section, we discuss related work in both mental models and explanations in intelligent systems. We regard our work as unique in that it applies an examination of mental models to a field study of an intelligent system. Our intent is to provide designers with practical knowledge that is more broadly applicable to other systems.

Mental models

Mental models are a hypothetical construct defined as a mental representation of a real or imagined situation [13]. Norman describes them as internal representations that provide predictive and explanatory power to users [22]. While rooted in psychology, mental models have also been used to evaluate shared understanding among work teams

[5], and to measure concept learning in educational settings

[6]. Psychological studies of mental models aim to understand how people develop and use these models by focusing on simple physical systems [25] or devices [14] with well-understood, explicit models of operation. While our study borrows from some of the elicitation methods used in this work, it is focused on mental models in the domain of intelligent systems as opposed to fundamental knowledge about the nature of mental models. Moray provides a theory of mental model development for expert users [18]. He states that instead of forming a completely accurate mental model, users will develop a reduced model that encompasses the majority of observed behavior. He describes these models as homomorphisms of the actual system model, where several inputs, or the relationships between them, may be coalesced into a single concept. By breaking down these homomorphic concepts into more detailed accounts of the system’s operation, a user could increase their understanding of the system. However, a particular model may become ingrained to the point that faults are addressed not by a rethinking of the user’s mental model, but by an attempt to fit the new behavior into the existing model. This “cognitive lockup” can be difficult to break, especially if the user has a large body of experience with the system and therefore a high degree of confidence in their mental model.

As we explain later, the results of our study showed that while participants simplified models by reducing the number of elements they believed our system was sensing, the structural complexity of their mental models was stable throughout the study. In the discussion section of this paper, we examine this result in light of Moray’s theories. Trust, explanation, and accountability Explanation has been one of the most frequently used methods for improving trust in intelligent systems [12] by making their behavior more observable [20]. Users have been shown to put greater trust in recommender systems when given additional explanations of the recommendations [11]. Suermondt and Cooper found that physicians using a medical expert system made fewer mistakes when provided with explanations of the system’s diagnoses [23]. Antifakos et al.showed that confidence levels could increase user trust in an intelligent notification system [1].

Along these lines, Dourish observed that the way a system presents its own state of operation has a strong influence on the way users perceive how their tasks on that system are being accomplished [7]. He argues that systems should provide accounts of their own operation that capture the inherent structure of system processes, revealing features deemed relevant and hiding unnecessary details. Bellotti and Edwards reiterate this point with respect to intelligent, context-aware systems, stating that such systems must be intelligible as to their states and intent in order for people to control their behavior [2]. To design for this sort of accountability, it is necessary to provide the appropriate abstractions from the implementation to the interface. By examining user mental models of an intelligent system that incorporates some explanatory power, our results can support accountability in design by reporting on the abstractions developed by people during normal use. Borgman used mental models to gauge the effectiveness of training techniques for an information retrieval system [4]. Her findings showed that subjects found it easier to describe the process of achieving tasks on the system rather than describing the system itself. More recently, Muramatsu and Pratt investigated how users’ mental models of search queries could be improved to correctly use concepts such as logical operators and stop words [21]. By conducting open-ended interviews both before and after users submitted a search query, they were able to assess deficiencies in

mental models and design appropriate explanations to correct them. We take a similar approach, but to a different class of system that incorporates probabilistic inference and machine learning.

METHODS

For this study, we designed and built a system to present estimates of the interruptibility of managers in an office setting. Since this system was intended to be used intermittently throughout the workday, we planned our study as a six-week field deployment. In this way, our

participants were afforded prolonged exposure to the system. By employing several methods of data collection, we were able to obtain a more realistic picture of how their mental models developed over time. Participants

We recruited four managers and nine of their direct reports from a local university’s human resources department. Their responsibilities ranged from payroll and benefits management for the university to coordination of temp services. Participants had no existing knowledge of programming or machine learning. The department was organized such that a small subset of our participants (managers) would generate estimates of interruptibility, while the remaining participants (direct reports) would use them in their work. In this situation, we would focus on the mental models of direct reports as opposed to the managers. Our rationale was that managers, by seeing their own interruptibility estimates, would have more time to monitor and even modify the estimates. In this way, they would develop an understanding of the system that was not achieved through normal work practice and would be less valid in the context of our study.

Our participants consisted of two six-person groups, each comprised of two managers and four of their direct reports (one of the direct reports, due to a hectic work schedule, had to leave the study after two weeks). These groups were split evenly into two different buildings about one city block apart, with little to no contact between them. Every manager had his/her own office and door, and all participants were located on the same floor of their respective buildings. Direct reports had either an individual office or cubicle. Communication was conducted primarily through email, office visits, and scheduled meetings, with occasional phone use. Instant messaging was not in use. Each direct report interacted primarily with only one of the managers in his/her group. All participants received movie theater gift cards as compensation. Interruptibility Estimates

Interruptibility estimates were obtained using sensor-based statistical models developed with Subtle, an extensible toolkit developed by Fogarty and Hudson [10]. A statistical model of interruptibility was constructed for each manager during a three-month pre-deployment training phase. The training phase consisted of prompting each manager once per hour for a self-report of their interruptibility. Potential features were then created by using a small set of operators to explore the available sensor events. Sensor events included input events (e.g., keyboard/mouse), window manager events, nearby wireless access points, and audio. Operators included the current value of a feature, its recent values within a given time window, and whether its value was above/below a learned threshold. The feature set was then filtered to remove equivalent, highly-correlated, or noisy features. Finally, the optimal feature set was selected using a wrapper-based selection method [16]. This approach has been previously demonstrated to produce reliable estimates of office worker interruptibility, with model estimates outperforming human observers [9]. While this paper is not focused on examining the reliability of sensor-based models of human interruptibility, it seems likely that a reasonable level of reliability is necessary before the consumers of interruptibility estimates will place confidence in those estimates. Table 1 therefore presents a very brief summary of the reliability of the interruptibility model for each manager. Model accuracy ranged from 93.8% to 98.2%, estimated using ten-fold cross-validation. We note that the individual models learned here contain some automatically-learned features that are clearly based on small nuances in an individual’s data, are unlikely to be generally applicable, and are difficult to interpret. This seemed to be a larger problem when more self-reports were available for a particular manager, as this provided more data in which the learning system could find such small details. Based on the relative importance of each feature in each learned model, we chose a subset that we felt were both important and interpretable. Only those features were presented to participants in the remainder of this work, and the presented accuracy column in Table 1 presents the accuracy of only those features for each manager. Existing Interruptibility Practices

Interviews conducted with direct reports before we deployed our system indicated that they rely chiefly on two pieces of information in order to determine interruptibility. The first is the state of the manager’s office door. If it is closed, this is a strong indicator that the manager is not to be disturbed. If open, coworkers then listen for the sound of talking within the office. If no talking is heard, the manager is usually understood to be available. Otherwise, a judgment call is made based on the presence and identities of other people in the office, the content of the manager’s Table 1. Summary of sensor-based estimate reliability.

F

u

l

l

M

o

d

e

l

A

c

c

u

r

a

c

y

T

r

u

e

I

n

t

F

a

l

s

e

I

n

t

T

r

u

e

N

o

n

-

I

n

t

F

a

l

s

e

N

o

n

-

I

n

t

A

’

R

O

C

A

r

e

a

P

r

e

s

e

n

t

e

d

A

c

c

u

r

a

c

y

Manager 1 98.2% 72 0 88 3 .996 86.5% Manager 2 98.1% 21 2 134 1 .994 95.0% Manager 3 93.8% 35 0 26 4 .976 93.8% Manager 4 94.8% 41 3 14 0 .977 94.8%

conversation, and the importance or urgency of the information the coworker needs to communicate. For instance, a manager engaged in a conversation about last night’s football game with the coworker across the hall would invite interruption, while being engaged in a business-related phone call would not.

To a lesser extent, some participants reported using the manager’s online calendar as a means of saving a trip down the hall. They reported instances where they had walked to the manager’s office only to find that the manager was either not in the office or holding a scheduled meeting there. In addition, several participants reported making eye contact with their managers and using subtle gestures to negotiate interruption, in a similar manner to that reported by Kendon and Ferber [15]. It should be noted that the system we deployed was not capable of sensing some of the cues participants relied on for determining interruptibility. For example, it could not sense door state, presence, the identity of a conversant, calendar information, or conversational topic. While this made it challenging for participants to apply their existing models of interruptibility, our results show that by the study’s end, participants retained few of their initial notions about what the system could sense.

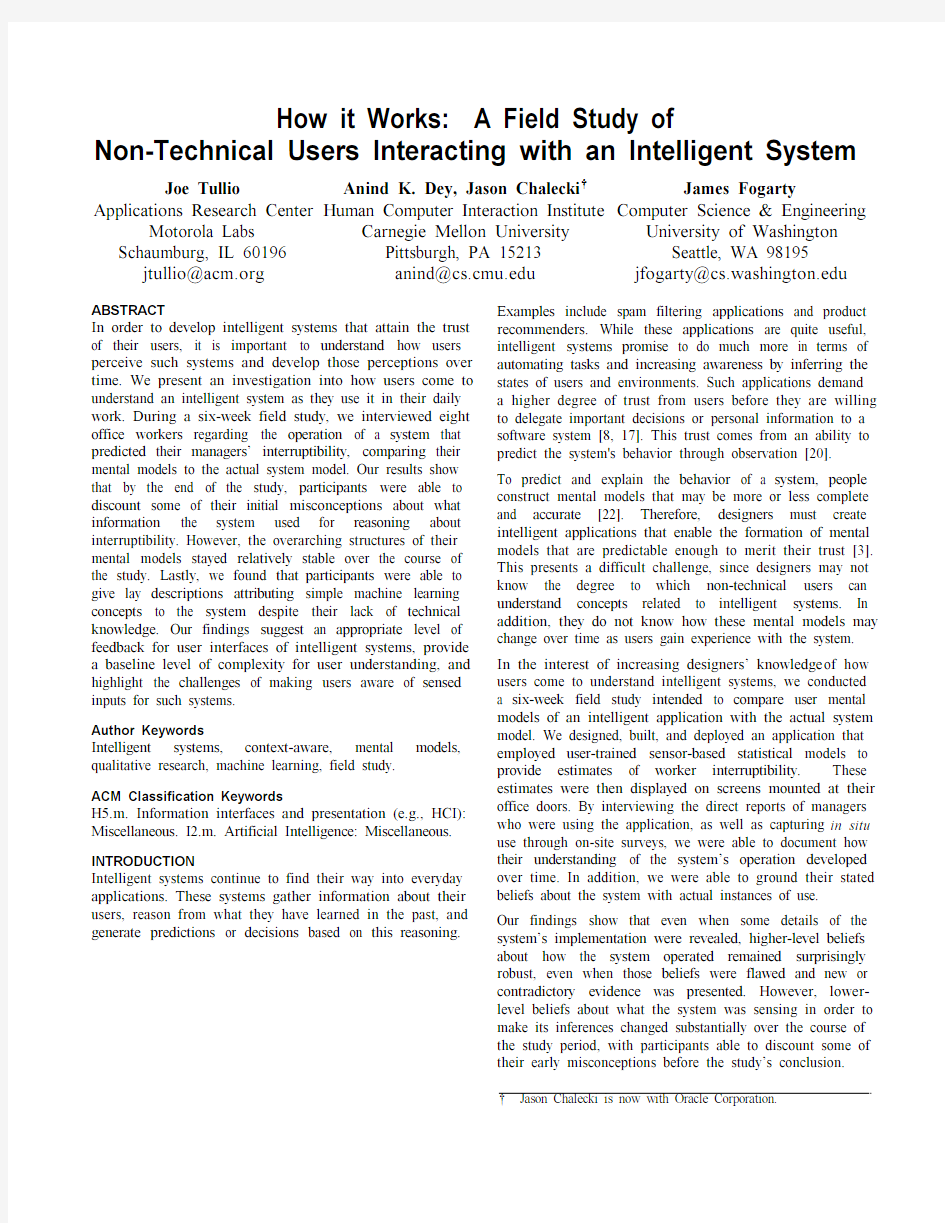

An interesting feature of the workplace was the existence of ceramic tags on each office door (Figure 1). These tags, participants told us, had been created to signal availability to coworkers who veered from the tacit open door/closed door policy that indicated interruptibility. The tags were painted green on one side and red on the other, acting as a “do not disturb” indicator when the red side was displayed. The problem with these tags, we were told, was that new employees had to be educated on their use, and that a fair amount of diligence was required to keep the state of the tags accurate. By the time our interviews were conducted, the tags had been present for several years, but the original proponents had since moved to a different building. Only a small fraction of employees, and none of our managers, still used the tags, and several still had the mistaken belief that they were in use by all of their coworkers. It should be noted here that none of our direct reports were under the impression that their managers were using the tags, so this existing system did not compete with our technology. Interruptibility Displays

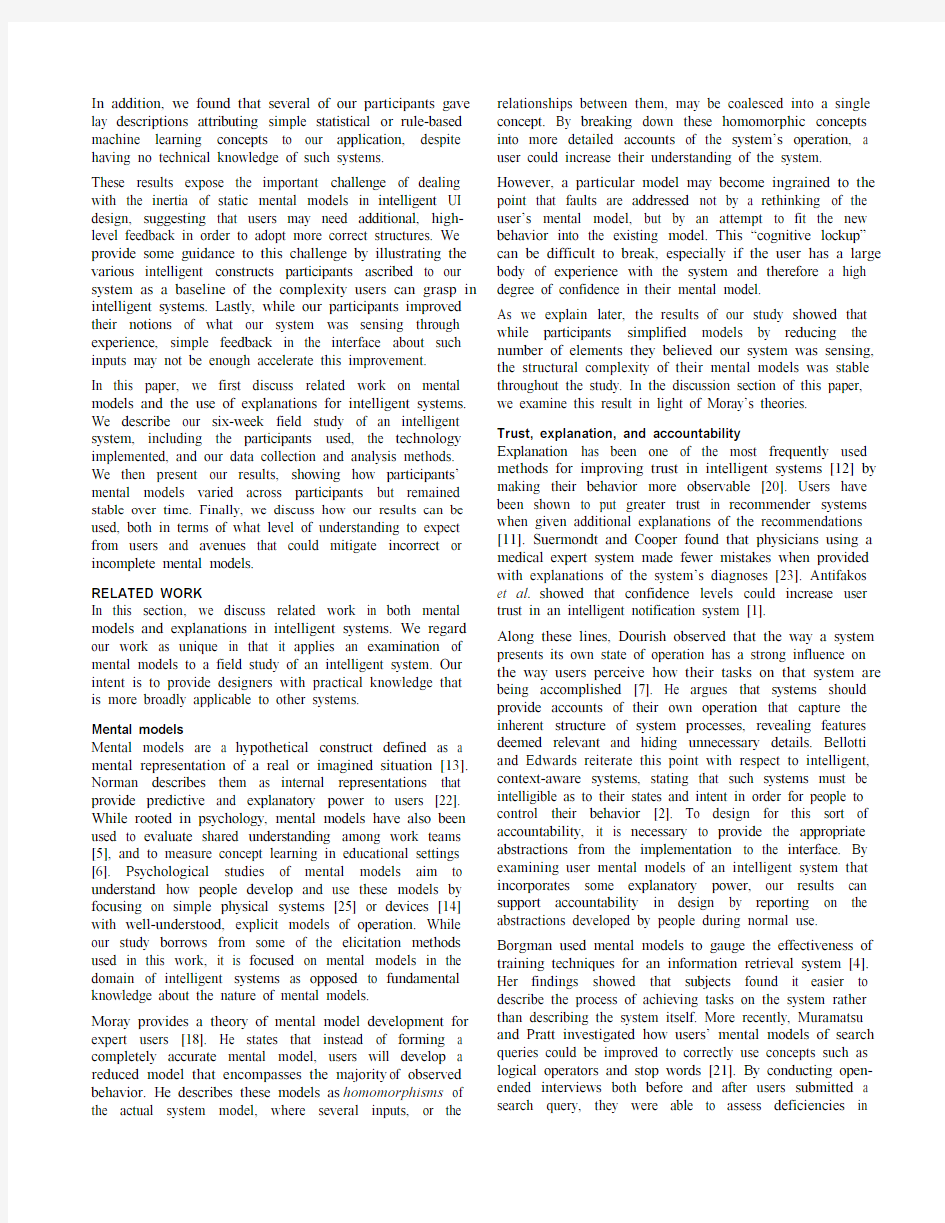

In designing our application, we made use of the existing door tags. Since most participants were familiar with them, we used the door tags as the basis for our application design, with a solid color used to represent interruptibility (Figure 2). A gradient scale below the color shows the position of the estimate on the overall scale, which runs from red (very uninterruptible) to green (very interruptible). Our display used this gradient to indicate its confidence, with the middle yellow region corresponding to situations where the learned model indicated that either value was equally likely. Informal user testing with 11 subjects confirmed that color codes, along with the gradient scale, were more accurately matched to interruptibility levels than photographs using different levels of transparency, levels of saturation, or gaze directions of subjects in photographs. As an additional constraint, some participating managers had reservations about having their photographs displayed in our interface. Lastly, when no estimates had been received from the manager’s computer for more than 10 minutes, the display would show a test pattern, usually indicating that the manager’s computer was turned off.

While the system was capable of further refining its statistical models once deployed, we opted to keep the models static after the training phase. We made this decision in order to simplify the process of comparing participant mental models with the actual system models. With continuous learning, the system models would change frequently, potentially at different rates for each manager. By avoiding this “moving target” problem, we could make more valid comparisons across participants and groups. In addition, feature representations within Subtle were not human-readable, requiring a level of abstraction to transform, for example, a particular computed property of ambient audio into a phrase such as “talking detected”.

While an abstraction of the low-level inputs, we feel these Figure 2. Screenshot of door display, with two relevant

features displayed beneath the color-coded estimate.

Figure 1. Door tags used onsite prior to our study.

human-readable descriptions did not diminish the accuracy of our portrayal of models.

Once the statistical models were built and their features labeled with human-readable text, they were installed on the managers’ computers. A separate program continuously served updated interruptibility estimates based on the current sensor data. These estimates were delivered via the university network to the door displays outside each office.

These displays took the form of 12” touch-sensitive color

LCDs that were stationed

outside the office doors of

each of our four managers (Figure 3). Since participants

in both sites were accustomed to frequent office visits and shared a common hallway, we were confident that they would have sufficient visibility for participants to notice them on a daily basis. The touch-sensitive screen was used for additional data collection, described later.

Providing accountability

Our two six-person groups were each given a different version of the door display user interface in order to examine whether the addition of feedback in the interface would improve users’ mental models of the system’s operation. In one condition, the system dynamically displayed up to three features that contributed the most information to the current interruptibility estimate, using a cross-entropy metric similar to that used by Suermondt and Cooper [23]. These features, which were specific to each manager’s user model, were then displayed at the bottom of the interface along with an associated icon (e.g., a keyboard icon for keyboard activity, speaker for audio activity, etc.). In this way, participants could see exactly what the most important sensors were, as well as their relative contributions to the estimates they were seeing. While estimates were updated continuously, the display itself was updated every 20 seconds to allow time to read the feature descriptions and minimize distraction. Participants in the other condition were able to see only the color-coded interruptibility estimates.

Data Collection

Our primary source of data collection was a series of five semi-structured interviews, each lasting between 30-60 minutes and recorded using both field notes and audio. The managers did not participate in these interviews; we were mainly interested in how their direct reports interpreted the interruptibility estimates generated for the managers. We

did, however, interview managers at the close of the study for their thoughts on the system’s usefulness.

The first of the five interviews were conducted prior to deploying our office displays. These interviews focused mainly on work practices, including job descriptions, the number of meetings per week with participating managers, meetings with other participants, and existing means of estimating interruptibility. The interview concluded with questions about how participants believed a system that predicts interruptibility might work, including what information the computer would use, and how this information might be synthesized into an estimate.

Eliciting technical information from non-technical users

After our system was deployed, we conducted four additional interviews at roughly one-week intervals. These interviews focused primarily on eliciting participants’ mental models of the system’s operation. Our initial concerns were that our participants, whose interaction with computers was primarily through a small set of office and communication applications and whose technical support was handled by the university’s IT department, would not be able to venture an opinion on the operation of a fairly sophisticated machine learning system.

However, as Norman has claimed [22], mental models evolve naturally as users interact with a system. Most useful to our interviews was breaking down the problem into four areas. First we solicited the set of sensors that participants believed were being used by the system. In other words, what was the computer capable of sensing that was relevant to interruptibility? Second, participants were asked for their beliefs on the relative importance of these sensors. Third, they were asked to explain how they thought these sensors were synthesized into an interruptibility estimate. Finally, they were asked to relate their experiences to this model as a means of confirming its validity. Each week participants were asked to describe some instances in which they noticed or used the office displays, and the role they played in choosing whether or not to interrupt a manager.

As a supplement to these interviews, a short (five question, multiple choice) survey was included on the office displays themselves for collecting some in situ information on the use of the displays. These questions asked the user to rate how important his/her need was to speak with the manager (5-point Likert scale), whether he/she would actually interrupt the manager, and whether that decision was based on the display, the status of the manager, or the importance of the information. Lastly, three 5-point Likert ratings were requested for the participant’s agreement with the estimate, the degree to which the display influenced their decision to talk to the manager, and their confidence in the display in absence of any other information.

Participants were encouraged, but not required, to complete the survey prior to visiting a manager’s office, while the

intent of the visit was still at the forefront of their attention.

Figure 3. Door display setup used in our study.

This convention was not always followed, as some visits were time-sensitive and could not be delayed by the survey. Upon the completion of a survey, a follow-up email to the participant would be triggered that would ask a few additional longer-form questions about the office visit. These questions asked what particular aspects of the office and the displays themselves contributed to the estimate on the display as well as the participant’s own personal estimate of interruptibility.

Data analysis

The structures of our participants’ mental models were coded by identifying several types of relationships and entities described during interviews. These included believed sensors used by the system that were listed by participants during interviews, conditions that involved making a decision based on the current state, connections that used the output of one element as the input to another, priority lists of activities or inputs were relevant, and patterns that consisted of activities or input levels that were learned over time and distinguishable by some software recognizer. In addition, participants mentioned history as a means by which patterns could be established. These coded models were then grouped by similarity into the four model types described in the next section.

RESULTS

After our deployment, we were left with a number of completed surveys documenting interactions with our door displays as well as coded interview data on participants’ mental models of the system’s operation. We present these results below.

Door display surveys

Forty-three surveys were completed at our door displays during the course of the study, with 19 of those completed anonymously. We learned later that two people in the office who were not officially part of the study had completed several surveys anonymously. All eight of the direct reports who participated completed at least one survey, with four of them completing at least four. Of the 43 surveys, 29 were completed in the first two weeks of the study. Across all surveys, there was a moderate degree of correlation between the influence of the system on participants’ decision-making and their confidence in relying on it exclusively for deciding whether or not to interrupt (Pearson’s r=0.48). There was a low correlation between the participants’ agreement with the system’s estimates and their confidence in relying on them exclusively (Pearson’s r=0.33). These results seem to indicate that users would rely on the system more if they have confidence in its predictions, but that they tend to trust their own estimates more. Only in nine of the surveys did participants report relying on the display to determine whether to interrupt. Average ratings for confidence in the displays (3.0/5.0, ±1.1) and their degree of influence (2.93/5.0, ±1.6) were higher than for agreement (2.75/5.0, ±1.3), though not significantly. Standard deviations were high, indicating that participants had either high or low degrees of faith in the system.

Fifteen follow-up email surveys were returned from seven of our participants. About half of them (8) were in agreement with the estimate presented on our displays. Of the remaining seven responses, two indicated that the manager had left the office, but was displayed as interruptible. The remaining surveys indicated that the system estimated too conservatively in those cases, predicting lower interruptibility than was the case, at least from the direct reports’ perspectives.

A shortcoming of our system was that we could not explicitly detect a person’s presence in the office. Therefore, the software would estimate interruptibility based on available sensors independent of whether the manager was in the office or not. This was a frequently cited problem in interviews, with participants mentioning that it also affected their responses on the door display surveys. Subsequently, our results in terms of participant agreement and confidence with respect to the system were likely affected by this issue.

Mental models

In eliciting mental models from participants, we asked for their beliefs concerning both the sensors that were being used by our system and the mechanism(s) to convert these inputs into an estimate of interruptibility. In this section, we start with participants’ responses on possible sensors before discussing the actual model structures.

System sensors

The most common factors participants believed were being used by our system included the calendar, the presence of talking, and keyboard/mouse activity. While the presence of calendar-related windows on the screen was influential in one manager’s model, the actual schedule itself was not used by our software. Mouse/keyboard activity was an influential sensor for three of the four managers, and the presence of talking was important to all of them.

An analysis of variance showed a significant effect of interview date on the number of sensors participants believed were being used by our system, F(1, 31) = 7.04, p < 0.05, with fewer sensors reported as the study progressed. However, there was no significant difference between those who received feedback about relevant features from the system’s statistical models and those who did not. By the final week, participants reported an average of only 1.75 of the sensors they believed were being used by the system during the first week. In interviews, participants reported ruling out a number of potential sensors for a variety of reasons. For example, one participant ruled out cameras as “too Big Brother”. Another ruled out audio because she noticed no change in the display after she had conducted a conversation within her manager’s office. Note that in the first case, the decision to rule out cameras made for a more correct model, while in the second, it became less correct since the system was in fact using audio.

We measured correctness by taking the sensors evaluated by each user model of interruptibility and comparing them to the inputs listed by participants. On average, participants listed nearly the same number of correct sensors (2.1) in the first week as the last week (2.0), with no significant difference between the groups with feedback and those without. Given that participants listed significantly fewer sensors at the end of the study, a higher percentage of those features were correct. An analysis of variance showed a significant improvement in correctness between participants’ beliefs for the first two interviews and those for the last three interviews, F(1,31) = 4.44, p < 0.05. Model structure

Despite using similar means to judge managers’ availability

prior to the study, participants reported a fairly diverse range of topologies in terms of how they thought the system was operating. These models varied in the ways they incorporated history, made use of statistics and in one case, whether the inferences were human or machine-generated. Our expectation, however, was that these models would change with time as participants gained experience with the system. Further, those participants who were provided with additional information about the features being used by the system were expected to develop more accurate mental models. What we found was that the overarching structures of their mental models remained for the most part stable throughout the study and having additional information had little impact. Later in our discussion, we remark on why this was the case and propose how the interface could trigger higher-level changes to users’ mental models. Simple set of rules

Two of our participants (one from each condition) believed that the system worked on a simple set of conditional rules to determine interruptibility. An example from one participant is given below:

Is the computer on?

?No: Display test pattern

?Yes: Next condition

Is the manager on the phone?

?Yes: Highly uninterruptible (bright red)

?No: Next condition

Are there voices in the room?

?Yes: Uninterruptible (red)

?No: Next condition

Is there an event on the calendar?

?Yes: Uninterruptible (red)

?No: …

Such rules would continue to be applied until a default value of green (interruptible) was reached. Though neither participant could explain fully where these rules originated, they both assumed that the training phase had some role in formulating them. Self-reported (Remote Control)

One participant held to the belief throughout our study that the display was controlled manually from inside the office by the manager. While one dialog used to collect training data could be that it is a “remote control” to manipulate the display, there was no overlap in the deployment of the training dialog and our door displays.. Therefore, this participant had no visual evidence to support this belief. However, this participant was not confident that a computer system could capture the factors inherent in assessing interruptibility, and therefore adopted the simpler avenue despite having little observational support for it. This mental model proved robust to mismatches between the manager’s displayed and actual interruptibility:

Interviewer: So why would the display say red even when [your manager] is available?

P: Well…maybe she finished whatever she was doing, but for one reason or another, hadn’t hit the key (to change the interruptibility level).

Also interesting was the fact that this participant was part of the group that received additional feedback on our door displays about relevant features used for the system’s estimate. Rather than interpreting these features as leading to the estimates shown, they were instead interpreted as being there to justify the estimate chosen by the manager and help the potential interrupter with their decision of whether or not to heed the display.

Prioritized cases

Two participants (one from each condition) described models incorporating the following elements:

? A prioritized list of activities ranging from most to least important to interruptibility,

? A recognizer of sorts to identify which activity is currently occurring from the sensor inputs,

?One or more conditional rules used to handle overriding situations or special cases.

One such model as described and confirmed by a participant is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. A diagram of one participant's mental model of the experimental system. System inputs are sent to a pattern

recognizer that uses a decision tree-like algorithm to

identify activities that are ordered by importance.

A list of activities might range from web browsing or checking email (low priority) to working on a large report or spreadsheet (high priority). Participants assumed that these priorities were determined during the training phase through either automated means or through interviews/observations of the managers.

In terms of recognition, participants described the system as using available sensor data to test a series of conditions that would establish which activity was occurring. To quote one participant, “…it has to be something like, you know, like a tree…if ‘yes’ then this, if ‘no’ then this.” This participant went on to describe a decision tree-style process by which the system builds its list of activities from past history and tests the current situation along a number of branching conditions to see if it matches anything in the list. Lastly, participants included additional rules outside of the main priority/recognition mechanism to account for special cases or observed behaviors. For example, one participant believed the presence of a calendar appointment would override any other recognized activity and immediately designate the manager as uninterruptible. Another participant added a “confused” state to the model to explain situations where one display appeared to fluctuate between several states within a short amount of time. Similarity to average

Three other participants articulated a model that, while similar structurally to the prioritized cases model described above, also explicitly incorporated the use of simple statistics to determine degrees of interruptibility. In two cases, this constituted a deviation from the mean level of activity sensed in the manager’s training data. In the third case, the participant described a more nebulous “calculation” that nonetheless relied on historical statistics to arrive at an estimate. In these cases, participants thought in terms of “levels” of activity rather than whether a particular activity was occurring or not. One participant described it this way:

P: For example, the number that it looks up tells it they’re not busy, but the number that this is coming up with is higher. Interviewer: Ok, so it has some sort of idea of, uh…

P: A baseline.

The “number” here refers to the average level of several inputs (mouse, keyboard, audio, etc.) that are associated in the training data with a certain level of activity.

We believe two main factors contributed to this belief. First, participants with these models associated the training phase of the study with a collection of “average” levels of activity for the various inputs. Second, these participants noted the continuous nature of the color scale used to display interruptibility and associated it with a continuous range of possible values. It is possible that the two participants who adopted the prioritized case-based model described previously did not make this association and therefore did not develop a statistics-based model. Of all the models described by participants, this class was most similar in structure and function to the actual system used. Most notably, this model incorporated the use of history and statistics, as well as some combination of sensor data with varying degrees of influence, to arrive at the final estimate. Interestingly, two of the three participants with this model came from the group that had no additional feedback about the features used by the system. In fact, none of the four types of models listed seemed to be related to whether the participants were given additional information about the features used. We address this finding in the discussion section. DISCUSSION

Here we review the major findings of our study and discuss their implications for future research and design of intelligent user interfaces.

Similarity to the system model

While none of our participants possessed a mental model that was identical to the system model, three participants developed a statistics-based mental model that used past experience to associate current sensor activity with an estimate of interruptibility. Elements of both the system’s training phase and user interface contributed to this understanding. At a basic level, we observed that for systems incorporating machine learning and estimates of current or future state, the key concepts of learning from history and statistical inference from current sensor data must be effectively communicated in the interface.

It was clear from our results that incorporating feedback about relevant features was of only moderate use in helping our participants understand the system’s operation. Participants had little success in retaining knowledge of these features from week to week, and perhaps more importantly, were unable to make higher-level structural adjustments to their mental models using this feedback. While all participants had some knowledge of the training phase prior to the deployment of our office door displays, not all of them incorporated this phase into their mental models. In addition, despite our use of a gradient scale to represent the continuous nature of the output, only about half of our participants regarded it in these terms, and fewer made the connection of this output to statistical patterns. Stability of structure

The fact that participants described basically the same model structure with each successive interview was somewhat surprising to us. We had expected participants to frequently modify their models as more observations were made of the system’s behavior and conversations with coworkers exposed them to alternative theories. As it turned out, they rarely discussed the system with one another, with some participants worried it would be considered “cheating”, even though we did not discourage it. The most significant changes to mental models came when participants incorporated additional inputs, removed others,

or tacked on conditions to handle special cases that were not covered by the existing model.

In addition, some mental models held up in light of conflicting experiences or clear deficiencies in terms of incorporating known components of the system, such as the training phase. In the case of the participant who saw the system’s estimates as the result of manual control, feedback about relevant features was regarded as auxiliary information, and the training application as being repurposed into a remote control. Moray’s theory of “cognitive lockup”, where operators maintain their beliefs about a system even in the face of contradictory evidence, may hold here, but this theory is intended for expert users with a grasp of the system’s normal operating parameters. Given that a number of our participants verbally expressed low confidence in their mental models at the end of the study, it may not be appropriate to regard them as experts after five weeks of experience.

Instead, it may be that the feedback provided was at too low a level to help participants in breaking out of their conceptualizations of the system’s mechanics. While the interface provided information about inputs and relevant features (in one condition), and clues to the probabilistic nature of the output by using a gradient scale, it provided no higher-level information on the features’ relationships to one another or the process used to relate those features to the training phase.

Retaining knowledge of sensors

In contrast to the stability we observed in model structure, participants showed that they were able to reduce the set of potential sensors they believed were used by our system over the course of the study. Moreover, they were able to achieve modest improvements in the correctness of these beliefs over time. Rather than using the feedback provided by our system, however, participants relied more on observations of the system’s behavior and reflective assessments of the feasibility of potential sensors.

For the group that was given additional information on model features, we noticed that with the exception of audio, in nearly every case where a new sensor was learned from the display in a given week, it was not reported again the following week. These included sensors for window focus events, nearby wireless access points, and keyboard/mouse activity. While these items were not used by participants to determine interruptibility prior to the introduction of our system, participants had consistently mentioned other events that also were not part of their existing practices. It is possible that much more exposure to this information is needed before it is retained. It is also possible that more technical aspects of the system such as window focus events are more difficult to remember than everyday or more familiar events/artifacts such as conversation, email, and calendars. Further study is needed to determine whether more technical inputs to intelligent systems require additional explanation or emphasis to learn. Understanding machine learning concepts

One of the more interesting findings of our study was that participants were able to ascribe basic machine learning concepts to our system despite being unfamiliar with the field. One participant described, in lay terms, the basic decision tree algorithm, while several others described the use of nested yes/no questions that demonstrated the use of decision trees without going into the details of their construction. In addition, over half of our participants described the use of “patterns” or “averages” gleaned from historical data as a means of predicting current or future states. While some of these patterns were described in terms of the decision tree-type structures just mentioned, others were described in terms of simple statistics such as deviation from the mean.

These results are encouraging in that, if demonstrated across a broader cross-section of the population, designers can potentially know what to expect in terms of user sophistication with respect to machine learning systems. In cases where the underlying algorithm makes little difference in terms of functionality, designers may consider using one that is closer to those described by our participants. If a more complex algorithm is needed, a simplified version that is closer to concepts readily understood by users could be presented in the interface. Reliability of interviews

An issue with our data collection method is the nature of mental models and the reliability with which they can be elicited. Norman claims that simply asking participants is less reliable than collecting data in the context of activities or problem solving [22]. The fact that our study was conducted in the field made it difficult to capture such instances reliably, as interactions at the doors happened at random points throughout the day, and the display itself was noticed peripherally regardless of whether one intended to meet with a manager. Knowing this might be the case, we used the survey data collected at the displays to help participants in re-creating their experiences with them, and also to assist in “running’ their mental models to explain how those experiences influenced them. In doing so, we follow the mental model elicitation technique favored by Morgan et al. who, as in our work, focus on less well-constrained domains [19]. The stability of model structure over time lends reliability to our data, given that we made participants describe the entire model at each interview. Overall, our interviewing method was similar to controlled studies of mental models mentioned earlier [14, 25]. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE WORK

A natural next step for this work will be to use our findings in the design of user interfaces that express a correct conceptual model to users. While several of our participants were on the right track in terms of understanding the use of history, statistics, and continuous evaluation of features to arrive at estimates, others were not aware of these key concepts and required more than knowledge of the features being used. Any design must illustrate these higher-level

concepts to assist users in breaking out of incomplete or incorrect mental models, such as those based on simple conditional rules. We hope to generate our designs for the interruptibility displays used in this study and evaluate their effects in a lab setting before returning to the field.

Our study is limited in terms of the domain of our application and our participants’ demographics. Additional work is needed in other application areas with different machine learning algorithms to establish a broader pattern of how users come to understand intelligent systems. Lastly, mainstream intelligent applications such as spam filters and recommenders incorporate adaptive user models that improve over time. By using static models, our study assumed a stable system and ignored any kind of learning phase. An interesting direction for this work would be to examine how user and system models co-evolve during such a learning phase.

In this paper we have described a field study of how users’ mental models develop around an intelligent system. We have shown that users are capable of attributing concepts of machine intelligence to our system. Designers can use these concepts to incorporate higher-level feedback in the user interface that could correct stable but flawed mental models. We have also shown that simple feedback about features used by our system was not enough to improve the rate at which users learned these features, and that more work is needed to ensure that users retain this knowledge. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Eric Horvitz for early discussions that inspired this work. Thank you also to Jen Mankoff, Elaine Huang, and Daniel Avrahami for their help on the paper and analysis. This material is based upon work supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) under Contract No. NBCHD030010, and by the National Science Foundation under grants IIS-0121560, IIS-0325351, and IIS-0205644. REFERENCES

1.Antifakos, S. Kern, N., Schiele, B., Schwaninger, A., (2005) Towards improving trust in context-aware systems by displaying system confidence. In Proc. MobileHCI 2005, pp. 9-14.

2.Bellotti, V. and Edwards, W.K. (2001) Intelligibility and Accountability: Human Considerations in Context-Aware Systems, Human-Computer Interaction, 16(2-4):193-212.

3.Birnbaum, L., Horvitz, E., Kurlander, D., Lieberman, H., Marks, J., and Roth, S. (1997). Compelling intelligent user interfaces—how much AI? In Proc. of IUI’97, pp. 173-175.

4.Borgman, C. (1986) The User’s Mental Model of an Information Retrieval System. ’Int’l Journal of Man-Machine Studies 24(1):47-64.

5.Cannon-Bowers, J.E., Salas, E., and Converse, S. (1993) Shared Mental Models in Expert Team Decision-Making,“ In Individual and Group Decision-Making: Current Issues, J. Castellan, (ed.), Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

6.Chi, M.T.H. (2000). Self-explaining expository texts: The dual processes of generating inferences and repairing mental models. In R. Glaser (Ed.), Advances in Instructional Psychology, Hillsdale, NJ:Erlbaum. pp. 161-238.

7.Dourish, P. (1995). Accounting for System Behaviour: Representation, Reflection and Resourceful Action. In Proc. of Conference on Computers in Context CIC'95, pp. 145-170.

8.Dzindolet, M., Peterson, S., Pomranky, S. Pierce, L. and Beck,

H. (2003) The role of trust in automation reliance, ’Int’l Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 58(6):697-718.

9.Fogarty, J., Hudson, S.E., and Lai, J. (2004). Examining the Robustness of Sensor-Based Statistical Models of Human Interruptibility. In Proc. of CHI 2004, pp. 207-214.

10.Fogarty, J. and Hudson, S.E. (2007) Toolkit Support for Developing and Deploying Sensor-Based Statistical Models of Human Situations. To Appear, CHI 2007.

11.Herlocker , J., Konstan , and J., Riedl, J. (2000) Explaining collaborative filtering recommendations, In Proc. of CSCW 2000, pp.241-250.

12.Johnson, H. and Johnson, P. (1993) Explanation facilities and interactive systems. In Proc. of IUI’93, pp. 159-166. 13.Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1983) Mental Models: Towards a Cognitive Science of Language, Inference, and Consciousness. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Press.

14.Kempton, W. (1987) Two theories of home heat control. In N. Quinn & D. Holland (Eds.) Cultural Models in Language and Thought, Cambridge University Press.

15.Kendon, A. and Ferber, A. (1973) A description of some human greetings. In R. Michael and J. Crook (Eds.), Comparative Ecology and Behavior of Primates, pp. 591-668. New York: Academic Press.

16.Kohavi, R. and John, G.H. (1997) Wrappers for Feature Subset Selection, Artificial Intelligence 97(1-2):273-324.

17.Maes, P. (1994) Agents that Reduce Work and Information Overload. Communications of the ACM, 37(7):31-40. 18.Moray, N. (1987) Intelligent Aids, Mental Models, and the Theory of Machines. ’Int’l Journal of Man-Machine Studies, 27 (5):619-629.

19.Morgan, M.G., Fischhoff, B., Bostrom, A. and Atman, C.J. (2002) Risk Communication: A Mental Models Approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

20.Muir, B. (1994) Trust in automation Part I: Theoretical issues in the study of trust and human intervention in automated systems. Ergonomics 37(11):1905-1922.

21.Muramatsu, J. and Pratt, W. (2001) Transparent Queries: Investigating Users’ Mental Models of Search Engines, In Proc. of SIGIR 2001, pp. 217-224.

22.Norman, D.A. (1983). Some observations on mental models. In D. Gentner & A.Stevens (Eds.) Mental Models, pp. 7-15. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

23.Suermondt, J. and Cooper, G. (1992) An Evaluation of Explanations of Probabilistic Inference. In Proc. Computer Applications in Medical Care, pp. 579-585.

https://www.doczj.com/doc/e62320986.html,ersky, A. and Kahneman, D. (1974) Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases, Science 185(4157):1124-1131.

25.Williams, M.D., Hollan, J.D., and Stevens, A.L. (1983) Human Reasoning about a Simple Physical System. In D. Gentner & A.Stevens (Eds.) Mental Models, pp. 131-154. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

如何写先进个人事迹 篇一:如何写先进事迹材料 如何写先进事迹材料 一般有两种情况:一是先进个人,如先进工作者、优秀党员、劳动模范等;一是先进集体或先进单位,如先进党支部、先进车间或科室,抗洪抢险先进集体等。无论是先进个人还是先进集体,他们的先进事迹,内容各不相同,因此要整理材料,不可能固定一个模式。一般来说,可大体从以下方面进行整理。 (1)要拟定恰当的标题。先进事迹材料的标题,有两部分内容必不可少,一是要写明先进个人姓名和先进集体的名称,使人一眼便看出是哪个人或哪个集体、哪个单位的先进事迹。二是要概括标明先进事迹的主要内容或材料的用途。例如《王鬃同志端正党风的先进事迹》、《关于评选张鬃同志为全国新长征突击手的材料》、《关于评选鬃处党支部为省直机关先进党支部的材料》等。 (2)正文。正文的开头,要写明先进个人的简要情况,包括:姓名、性别、年龄、工作单位、职务、是否党团员等。此外,还要写明有关单位准备授予他(她)什么荣誉称号,或给予哪种形式的奖励。对先进集体、先进单位,要根据其先进事迹的主要内容,寥寥数语即应写明,不须用更多的文字。 然后,要写先进人物或先进集体的主要事迹。这部分内容是全篇材料

的主体,要下功夫写好,关键是要写得既具体,又不繁琐;既概括,又不抽象;既生动形象,又很实在。总之,就是要写得很有说服力,让人一看便可得出够得上先进的结论。比如,写一位端正党风先进人物的事迹材料,就应当着重写这位同志在发扬党的优良传统和作风方面都有哪些突出的先进事迹,在同不正之风作斗争中有哪些突出的表现。又如,写一位搞改革的先进人物的事迹材料,就应当着力写这位同志是从哪些方面进行改革的,已经取得了哪些突出的成果,特别是改革前后的.经济效益或社会效益都有了哪些明显的变化。在写这些先进事迹时,无论是先进个人还是先进集体的,都应选取那些具有代表性的具体事实来说明。必要时还可运用一些数字,以增强先进事迹材料的说服力。 为了使先进事迹的内容眉目清晰、更加条理化,在文字表述上还可分成若干自然段来写,特别是对那些涉及较多方面的先进事迹材料,采取这种写法尤为必要。如果将各方面内容材料都混在一起,是不易写明的。在分段写时,最好在每段之前根据内容标出小标题,或以明确的观点加以概括,使标题或观点与内容浑然一体。 最后,是先进事迹材料的署名。一般说,整理先进个人和先进集体的材料,都是以本级组织或上级组织的名义;是代表组织意见的。因此,材料整理完后,应经有关领导同志审定,以相应一级组织正式署名上报。这类材料不宜以个人名义署名。 写作典型经验材料-般包括以下几部分: (1)标题。有多种写法,通常是把典型经验高度集中地概括出来,一

小学生个人读书事迹简介怎么写800字 书,是人类进步的阶梯,苏联作家高尔基的一句话道出了书的重要。书可谓是众多名人的“宠儿”。历来,名人说出关于书的名言数不胜数。今天小编在这给大家整理了小学生个人读书事迹,接下来随着小编一起来看看吧! 小学生个人读书事迹1 “万般皆下品,惟有读书高”、“书中自有颜如玉,书中自有黄金屋”,古往今来,读书的好处为人们所重视,有人“学而优则仕”,有人“满腹经纶”走上“传道授业解惑也”的道路……但是,从长远的角度看,笔者认为读书的好处在于增加了我们做事的成功率,改善了生活的质量。 三国时期的大将吕蒙,行伍出身,不重视文化的学习,行文时,常常要他人捉刀。经过主君孙权的劝导,吕蒙懂得了读书的重要性,从此手不释卷,成为了一代儒将,连东吴的智囊鲁肃都对他“刮目相待”。后来的事实证明,荆州之战的胜利,擒获“武圣”关羽,离不开吕蒙的“运筹帷幄,决胜千里”,而他的韬略离不开平时的读书。由此可见,一个人行事的成功率高低,与他的对读书,对知识的重视程度是密切相关的。 的物理学家牛顿曾近说过,“如果我比别人看得更远,那是因为我站在巨人的肩上”,鲜花和掌声面前,一代伟人没有迷失方向,自始至终对读书保持着热枕。牛顿的话语告诉我们,渊博的知识能让我们站在更高、更理性的角度来看问题,从而少犯错误,少走弯路。

读书的好处是显而易见的,但是,在社会发展日新月异的今天,依然不乏对读书,对知识缺乏认知的人,《今日说法》中我们反复看到农民工没有和用人单位签订劳动合同,最终讨薪无果;屠户不知道往牛肉里掺“巴西疯牛肉”是犯法的;某父母坚持“棍棒底下出孝子”,结果伤害了孩子的身心,也将自己送进了班房……对书本,对知识的零解读让他们付出了惨痛的代价,当他们奔波在讨薪的路上,当他们面对高墙电网时,幸福,从何谈起?高质量的生活,从何谈起? 读书,让我们体会到“锄禾日当午,汗滴禾下土”的艰辛;读书,让我们感知到“四海无闲田,农夫犹饿死”的无奈;读书,让我们感悟到“为报倾城随太守,西北望射天狼”的豪情壮志。 读书的好处在于提高了生活的质量,它填补了我们人生中的空白,让我们不至于在大好的年华里无所事事,从书本中,我们学会提炼出有用的信息,汲取成长所需的营养。所以,我们要认真读书,充分认识到读书对改善生活的重要意义,只有这样,才是一种负责任的生活态度。 小学生个人读书事迹2 所谓读一本好书就是交一个良师益友,但我认为读一本好书就是一次大冒险,大探究。一次体会书的过程,真的很有意思,咯咯的笑声,总是从书香里散发;沉思的目光也总是从书本里透露。是书给了我启示,是书填补了我无聊的夜空,也是书带我遨游整个古今中外。所以人活着就不能没有书,只要爱书你就是一个爱生活的人,只要爱书你就是一个大写的人,只要爱书你就是一个懂得珍惜与否的人。可真所谓

个人先进事迹简介 01 在思想政治方面,xxxx同学积极向上,热爱祖国、热爱中国共产党,拥护中国共产党的领导.利用课余时间和党课机会认真学习政治理论,积极向党组织靠拢. 在学习上,xxxx同学认为只有把学习成绩确实提高才能为将来的实践打下扎实的基础,成为社会有用人才.学习努力、成绩优良. 在生活中,善于与人沟通,乐观向上,乐于助人.有健全的人格意识和良好的心理素质和从容、坦诚、乐观、快乐的生活态度,乐于帮助身边的同学,受到师生的好评. 02 xxx同学认真学习政治理论,积极上进,在校期间获得原院级三好生,和校级三好生,优秀团员称号,并获得三等奖学金. 在学习上遇到不理解的地方也常常向老师请教,还勇于向老师提出质疑.在完成自己学业的同时,能主动帮助其他同学解决学习上的难题,和其他同学共同探讨,共同进步. 在社会实践方面,xxxx同学参与了中国儿童文学精品“悦”读书系,插画绘制工作,xxxx同学在班中担任宣传委员,工作积极主动,认真负责,有较强的组织能力.能够在老师、班主任的指导下独立完成学院、班级布置的各项工作. 03 xxx同学在政治思想方面积极进取,严格要求自己.在学习方面刻苦努力,不断钻研,学习成绩优异,连续两年荣获国家励志奖学金;作

为一名学生干部,她总是充满激情的迎接并完成各项工作,荣获优秀团干部称号.在社会实践和志愿者活动中起到模范带头作用. 04 xxxx同学在思想方面,积极要求进步,为人诚实,尊敬师长.严格 要求自己.在大一期间就积极参加了党课初、高级班的学习,拥护中国共产党的领导,并积极向党组织靠拢. 在工作上,作为班中的学习委员,对待工作兢兢业业、尽职尽责 的完成班集体的各项工作任务.并在班级和系里能够起骨干带头作用.热心为同学服务,工作责任心强. 在学习上,学习目的明确、态度端正、刻苦努力,连续两学年在 班级的综合测评排名中获得第1.并荣获院级二等奖学金、三好生、优秀班干部、优秀团员等奖项. 在社会实践方面,积极参加学校和班级组织的各项政治活动,并 在志愿者活动中起到模范带头作用.积极锻炼身体.能够处理好学习与工作的关系,乐于助人,团结班中每一位同学,谦虚好学,受到师生的好评. 05 在思想方面,xxxx同学积极向上,热爱祖国、热爱中国共产党,拥护中国共产党的领导.作为一名共产党员时刻起到积极的带头作用,利用课余时间和党课机会认真学习政治理论. 在工作上,作为班中的团支部书记,xxxx同学积极策划组织各类 团活动,具有良好的组织能力. 在学习上,xxxx同学学习努力、成绩优良、并热心帮助在学习上有困难的同学,连续两年获得二等奖学金. 在生活中,善于与人沟通,乐观向上,乐于助人.有健全的人格意 识和良好的心理素质.

优秀党务工作者事迹简介范文 优秀党务工作者事迹简介范文 ***,男,198*年**月出生,200*年加入党组织,现为***支部书记。从事党务工作以来,兢兢业业、恪尽职守、辛勤工作,出色地完成了各项任务,在思想上、政治上同党中央保持高度一致,在业务上不断进取,团结同事,在工作岗位上取得了一定成绩。 一、严于律己,勤于学习 作为一名党务工作者,平时十分注重知识的更新,不断加强党的理论知识的学习,坚持把学习摆在重要位置,学习领会和及时掌握党和国家的路线、方针、政策,特别是党的十九大精神,注重政治理论水平的提高,具有坚定的理论信念;坚持党的基本路线,坚决执行党的各项方针政策,自觉履行党员义务,正确行使党员权利。平时注重加强业务和管理知识的学习,并运用到工作中去,不断提升自身工作能力,具有开拓创新精神,在思想上、政治上和行动上时刻同党中央保持高度一致。 二、求真务实,开拓进取 在工作中任劳任怨,踏实肯干,坚持原则,认真做好学院的党务工作,按照党章的要求,严格发展党员的每一个步骤,认真细致的对待每一份材料。配合党总支书记做好学院的党建工作,完善党总支建设方面的文件、材料和工作制度、管理制度等。

三、生活朴素,乐于助人 平时重视与同事间的关系,主动与同事打成一片,善于发现他人的难处,及时妥善地给予帮助。在其它同志遇到困难时,积极主动伸出援助之手,尽自己最大努力帮助有需要的人。养成了批评与自我批评的优良作风,时常反省自己的工作,学习和生活。不但能够真诚的指出同事的缺点,也能够正确的对待他人的批评和意见。面对误解,总是一笑而过,不会因为误解和批评而耿耿于怀,而是诚恳的接受,从而不断的提高自己。在生活上勤俭节朴,不铺张浪费。 身为一名老党员,我感到责任重大,应该做出表率,挤出更多的时间来投入到**党总支的工作中,不找借口,不讲条件,不畏困难,将总支建设摆在更重要的位置,解开工作中的思想疙瘩,为攻坚克难铺平道路,以支部为纽带,像战友一样团结,像家庭一样维系,像亲人一样关怀,践行入党誓言。把握机遇,迎接挑战,不负初心。

主要事迹简介怎么写 概括?简要地反映?个单位(集体)或个?事迹的材料。简要事迹不?定很短,如果情况 多的话,也有?千字的。简要事迹虽然“简要”,但切忌语?空洞,写得像?学?期末鉴定。 ?应当以事实来说话。简要事迹是对某单位或个?情况概括?简要地反映情况,?如有三个??很突出,就写三个??,只是写某???时,要把主要事迹突出出来。 简要事迹?般来说,?少要包括两个??的内容。?是基本情况。简要事迹开头,往往要??段?字来表述?些基本情况。如写?个单位的简要事迹,应包括这个单位的?员、 承担的任务以及?段时间以来取得的主要成绩。如写个?的简要事迹,应包括该同志的性 别、出?年?、参加?作时间、籍贯、民族、?化程度以及何时起任现职和主要成绩。这 样上级组织在看了材料的开头,就会对这个单位或个?有?个基本印象。?是主要特点。 这是简要事迹的主体部分,最突出的事例有?个??就写成?块,并按照?定的逻辑关系进 ?排列,把同类的事例排在?起,?个??通常由?个?然段或?个?然段组成。 写作时,特别要注意以下四点: 1.?第三?称。就是把所要写的对象,是集体的?“他们”来表述,是个?的称之为“他(她)”。 (她)”,单位可直接写名称,个?可写其姓名。 为了避免连续出现?个“他们”或“他 2.掌握好时限。?论是单位或个?的简要事迹,都有?个时间跨度,既不要扯得太远,也不 要故意混淆时间概念,把过去的事当成现在的事写。这个时间跨度多长,要根据实际情况 ?定。如上级要某个同志担任乡长以来的情况就写他任乡长以来的事迹;上级要该同志两年 来的情况,就写两年来的事迹。当然,有时为了需要,也可适当地写?点超过这个时间的 背景情况。 3.?点他?的语?。就是在写简要事迹时,可?些群众的语?或有关?员的语?,这样会给??种?动、真切的感觉,衬托出写作对象?较?的思想境界。在?他?语?时,可适当加?,但不能造假。 4.?事实说话。简要事迹的每?个??可分为多个层次,?个层次先??句话作为观点,再???两个突出的事例来说明。?事实说话时,要尽量把?个事例说完整,以给?留下深 刻印象。

树立榜样的个人事迹简介怎么写800字 榜样是阳光,温暖着我们的心;榜样如马鞭,鞭策着我们努力奋斗;榜样似路灯,照亮着我们前进的方向。今天小编在这给大家整理了树立榜样传递正能量事迹作文,接下来随着小编一起来看看吧! 树立榜样传递正能量事迹1 “一心向着党”,是他向着社会主义的坚定政治立场;“人的生命是有限的,可是,为人民服务是无限的,我要把有限的生命投入到无限的为人民服务中去”,是他的至理名言;“甘学革命的“螺丝钉”,是他干一行爱一行、钻一行的爱岗敬业态度。他——雷锋,是我们每一个人的“偶像”…… 雷锋的事迹传遍大江南北,他,曾被人们称为可敬的“傻子”。一九六零年八月,驻地抚顺发洪水,运输连接到了抗洪抢险命令。他强忍着刚刚参加救火工作被烧伤的手的疼痛,又和战友们在上寺水库大坝连续奋战了七天七夜,被记了一次二等功。望花区召开了大生产号召动员大会,声势很大,他上街办事,正好看到这个场面,他取出存折上在工厂和部队攒的200元钱,那时,他的存折上只剩下了203元,就跑到望花区党委办公室要为之捐献出来,为建设祖国做点贡献,接侍他的同志实在无法拒绝他的这份情谊,只好收下一半。另100元在辽阳遭受百年不遇洪水的时候,他捐献给了正处于水深火热之中的辽阳人民。在我国受到严重的自然灾害的情况下,他为国家建设,为灾区捐献出自已的全部积蓄,却舍不得喝一瓶汽水。就这样,他毫不犹豫的捐出了自己的所有积蓄,不求功名,不求名利,只求自己心安理得,只求为

革命献出自己的微薄之力,甘愿做革命的“螺丝钉”——在一次施工任务中,他整天驾驶汽车东奔西跑,很难抽出时间学习,他就把书装在挎包里,随身带在身边,只要车一停,没有其他工作时,就坐在驾驶室里看书。他曾经在自己的日记中写下这样一段话:”有些人说工作忙,没时间学习,我认为问题不在工作忙,而在于你愿不愿意学习,会不会挤时间来学习。要学习的时间是总是有的,问题是我们善不善于挤,愿不愿意钻。一块好好的木板,上面一个眼也没有,但钉子为什么能钉进去呢?这就是靠压力硬挤进去的。由此看来,钉子有两个长处:一个是挤劲,一个是钻劲。我们在学习上也要提倡这种”钉子“精神,善于挤和钻。”这就是他,用自己的实际行动来证明自己,用自己的亲生经历来感化世人,用自己的所作所为来传颂古今……人们都拼命地学习他的精神,他的精神被不同肤色的人所敬仰。现在,一切都在变,但是,那些决定人类向前发展的基本要素没有变,那些美好的事物没有变,那些所谓的“螺丝钉”精神没有变——而这正是他的功劳,是他开启了无私奉献精神的大门,为后人树立了做人的榜样…… 这就是他,一位中国家喻户晓的全心全意为人民服务的楷模,一位共产主义战士!他作为一名普通的中国人民解放军战士,在他短暂的一生中却助人无数。而且,伟大领袖毛泽东主席于1963年3月5日亲笔为他题词:“向雷锋同志学习”。 正是因为如此,全国刮起了学习雷锋的热潮。雷锋已经离开我们很长时间了。但是雷锋的精神却深深地在所有中国人心中扎下了根,现在它已经长成一株小树。正以其顽强的生命力,茁壮成长。我坚信,

大学生先进事迹简介怎么写 苑xx,男,汉族,1990年07月22日出生,中国共青团团员,入党积极分子,现任xx学院电气优创0902班班长,担任xx学院09级总负责人、xx学院团委学生会科创部干事、xx学院文艺团主持部部长。 步入大学生活一年以来,他思想积极,表现优秀,努力向党组织靠拢,学习刻苦,品学兼优,工作认真负责,脚踏实地,生活勤俭节约,乐于助人。一直坚持多方面发展,全面锻炼自我,注重综合能力、素质拓展能力的培养。再不懈的努力下获得了多项荣誉: ●获得09-10学年xx大学“百佳千优”(文化体育)一等奖学金和“百佳千优”(班级建设)二等奖学金; ●获得09-10学年xx大学“优秀学生干部”荣誉称号; ●2010年xx大学普通话知识竞赛中获得一等奖; ●2010年xx大学主持人大赛中获得一等奖,被评为金话筒; ●xx学院首届“大学生文明修身”活动周——再生比赛中获得一等奖; ●xx学院首届“大学生文明修身”活动周——演讲比赛中获得一等奖。 一、刻苦钻研树学风 作为班长,他在学习方面,将班级同学分成各个学习小组,布置每日学习任务,分组竞争,通过开展各项趣味学习活动,全面调动班级同学的积极性,如:排演英语戏剧、文学常识竞答、数学辅导小组等。他带领全班同学努力学习、勤奋刻苦,全班同学奖学金获得率达91%,四级通过率达66%。 二、勤劳负责建班风

在日常班级工作中,他尽心尽力,通过网络组织建立班级博客,把班级的日常情况,班级比赛,特色主题班会等活动,及时上传到 班级博客,以方便更多同学了解自己的班级,也把班级的魅力、特色,更全面、更具体的展现出来。 在班级建设中,他带领全班同学参加学院组织的各项文体活动中也收获颇多: ●在xx学院首届“大学生文明修身”活动周中荣获第二名, ●xx学院首届乒乓球比赛中荣获第一名、精神文明奖, ●在xx学院“迎新杯”男子篮球赛中荣获第四名、最佳组织奖。 除了参加学院组织的各项活动外,为了进一步丰富班级同学们的课余生活,他在班级内积极开展各式各样的课余活动: ●普通话知识趣味比赛,感受中华语言的魅力,复习语文文学常识,为南方同学打牢普通话基础,推广普通话知识。 ●“我的团队我的班”主题班会活动中,创办特色活动“情暖你我心”天使行动,亲切问候、照顾其他同学的生活、学习方面细节 小事,即使在寒冷的冬天,也要让外省的同学感受到家一样的温暖。 ●“预览科技知识”科技宫之行,作为现代大学生,不能只顾书本知识,也要跟上时代,了解时代前沿最新科技。 ●感恩节“感谢我们身边的人”主题班会活动,在这个特殊的节日里,他带领同学们通过寄贺卡、送礼物等方式,来感谢老师辛勤 的付出;每人写一封家书,寄给父母,感谢父母劳苦的抚育,把他们 的感激之情,转化为实际行动来感化周围的人;印发感恩宣传单,发 给行人,唤醒人们的感恩的心。 三、热情关怀暖人心 生活中,他更能发挥榜样力量,团结同学,增强班级凝聚力。时刻观察每一位同学的情绪状态,在心理上帮助同学。他待人热情诚恳,积极帮助生活中有困难的同学:得知班级同学生病高烧,病情 严重,马上放下午饭,赶到同学寝室,背起重病同学到校医院进行

个人事迹简介 我是来自计算机与与软件学院的学生,现在为青年志愿者协会的干事,在班级担任生活委员。在过去的一年里,我注重个人能力的培养积极向上,热心公益,服务群众,奉献社会,热忱的投身于青年支援者的行动中!一年时间虽短,但在这一年的时间里,作为一名志愿者,我确信我成长了很多,成熟了很多。“奉献、友爱、互助、进步”这是我们志愿者的精神,在献出爱心的同时,得到的是帮助他人的满足和幸福,得到的是无限的快乐与感动。路虽漫漫,吾将上下而求索!在以后的日子里,我会在志愿者事业上做的更好。 在思想上,我积极进取,关心国家大事,并多次与同学们一起学习志愿者精神,希望我们会在新的世纪里继续努力,发扬我国青年的光传统,不懈奋斗,不断创造,奋勇前进,为实现中华民族的伟大复兴做出了更大的贡献。 在学习上刻苦认真,抓紧时间,不仅学习好学科基础知识,更加学好专业课知识,在课堂上积极配合老师的教学,乐意帮助其它同学,有什么好的学习资料,学习心得也与他们交流,希望大家能共同进步。在上一个年度总成绩在班级排名第四,综合考评在班级排名第二。在工作中,我认真负责,出色的完成老师、同学交给的各项任务,所以班级人际关系良好。

此外参加了学院组织的活动,并踊跃地参加,发挥自己的特长,为班级争得荣誉。例如:参加校举办的大合唱比赛并获得良好成绩;参加了计算机与软件学院党校学习并顺利结业;此外,参加了计算机与软件进行的“计算机机房义务打扫与系统维护”的活动。在这些活动中体验到了大学生生活的乐趣。 现将多次参与各项志愿活动汇报如下:2013年10月26日,参加计算机与软件学院团总支实践部、计算机与软件学院青年志愿者协会组织“志愿者在五福家园的健身公园开展义务家教招新活动”;2013年11月7日,参加组成计算机与软件学院运动员方阵在田径场参加学院举办的学校运动会;2013年12月5日,参与学校学院组织的”一二.五“大合唱比赛;2014年3月12日,参加由宿舍站长组织义务植树并参与植树活动;2014年3月23日,在计算机与软件学院团总支书记茅老师的带领下,民俗文化传承协会、计算机与软件学院青年志愿者协会以及学生会的同学们参观了“计算机软件学院的文化素质教育共建基地--南京市民俗博物馆”的活动;2014年3月26日,参加有宿舍站长组织的“清扫宿舍公寓周围死角垃圾”的活动;2014年4月5日,参加由校青年志愿者协会、校实践部组织的“南京市雨花台扫墓”活动,2014年4月9日,作为班级代表参加计算机软件学院组织部组织的“计算机应用office操作大赛”的活动。 在参与各项志愿活动的同时,我的学习、工作、生活能力得到了提高和认可,丰富生活体验,提供学习的机会,提供学习的机会。

《个人事迹简介》 个人事迹简介(一): 李维波,男,中共党员,自2003年应聘农电工以来,他就把自己的一切奉献给了他热爱的电力事业。在多年的工作中爱岗敬业,勤勤恳恳,任劳任怨。2003年至2007年先后担任过xx供电所线损管理员、用电检查管理员、两率管理员、线路工作负责人;2007年调到xx供电所任用电检查管理员、客户经理;2009年5月调到xx供电所任营销员兼用电检查管理员。 刚踏入电力工作的时候,他还是个电力行业的门外汉,可他深深的明白:知识改变思想!思想改变行动!行动决定命运这句话,明白在当今学习的社会里,对于电力更就应不断的吸取新的知识,更新新的观念,以满足时代对于电力的更高的要求。正是这样他透过自己的努力学习,一步步的从门外汉变成了此刻的技术骨干。 一、加强政治学习,提高理论思想水平 多年以来,他在工作中始终坚持学习邓小平理论和三个代表重要思想。他深知:一个人只有有了与时俱进的思想做指导,人的认识才会提高,思想才能净化,行为也才能与时代同步,与社会同步,与发展同步,也才能成为社会发展的推动者、有作为者,正因为如此,他严格要求自己,认真学习思想理论方面的知识,抓紧一切时间学习,认真听,做好笔记,写好心得,并且用三个代表思想来约束自己,不断提高自身的修养,从而真正实践党的全心全意为人民服务的宗旨。 二、加强专业知识的学习,提高专业技术 在当今信息化的时代,科学技术飞速发展,尤其在电力行业这个技术密集型企业中,学习显得尤为重要。从踏进电力企业的大门开始,他就自觉学习专业知识,以书本为老师,阅读各方面的相关书籍,不断丰富自己的理论基础;以老同志为师傅,细心观察他们的实际操作,不断丰富自己的实践经验;以实践为老师,从中加深对知识的理解和领会。从2003年开始,学会了计算机普通操作,掌握了电力安全方面相关知识、电工基础知识、供电营业规则,参加局每年安规考试多次得到全局前十名,2005年农电体制改革考试应知和应会总分全局第5名。 三、发扬三千精神,做好优质服务 2007年,xx所因滩坑移民影响,电费回收率难以上升,应对电费回收的复杂严峻形势,

员工主要事迹写法: xx,一个普通的名字。一个平凡的身影,经常出现在酒店的各个区域巡视。他是保安部副主管。 xx,自20xx年x月份进入酒店工作以来,一直表现出色,爱岗敬业,努力学习业务知识,也因此由一名普通保安员逐步成长为酒店一名管理人员,在20xx年x月正式接手保安部副主管一职。同年6月,参加宁波消防安全管理员的培训,并拿到了相应的资格证书。 作为酒店一名基层管理者,他处处起到了模范带头的作用,他的工作态度会影响整个团队,正所谓:火车跑得快,全靠车头带。在日常工作中他不怕困难,勇于承担责任,用在工作上,就是那份执着、坚定、信念。每当这时,他总是憨厚的笑笑:“还是领导有方,我只是一个执行者罢了”! 20xx年x月份,根据国家气象局预报的台风预测消息,第9号强台风“梅花”正向本地移动,可能在6日夜间在浙江省中北部沿海登陆,或紧擦宁波市沿海北上,但不管哪种路线都将对宁波造成严重影响。我酒店在林总经理的号召下,立即由工程部张经理带领工程保安部及各部门相关人员迅速成立临时抗台小组。xx也同时参加了前期各项准备工作,并同相关人员一同在酒店蹲守两个日夜,直至“梅花”绕道离开。他还开玩笑说:“这个日子很特别,七夕情人节碰上了梅超风”。

20xx年,对于酒店保安部来说,是较为艰辛的一年,由于市场原因,使得保安部人力处于紧张状态,即使如此,他还是较为圆满的完成了部门的各项培训及其它各项工作,并在xx月份对酒店全员进行了为期三天的消防知识培训,用自己所学到的知识来跟大家一起分享。同月底,在酒店各层领导的组织与鼓励下圆满的完成了消防模拟演习,事后他说:“大家都比我做的好,我还要努力加强学习啊”。 20xx年底,酒店餐饮客情非常好,餐饮部自身人员不能满足服务需求,需要其他部门帮工跑菜,这个问题也就落在了工程保安部的肩上。每天在厨房都能看到那一身保安制服的跑菜员,不用问,那肯定是xx。仅x月份,他在做好自己本职工作的同时,利用非当班时间帮工累计56小时。当然也有其他部门的帮工人员,他们都是优秀的,正是有这些非常优秀的员工,使得酒店营业部门顺利完成了各项任务。每当这时,他又会说:“我虽然是过来帮忙的,但我要把它当成自己的本职工作来做”。 20xx年底,临近春节,好多员工都想回家过年,保安部员工也不例外,但人员紧张怎么办呢,他又给大家做思想工作,同时分开安排人员回家的假期,以保证春节期间的正常排班,保障酒店的正常运行。但谁能知道他在酒店工作三年多了,每年的春节都是在酒店过的,每年的中秋节也都是在酒店过的,难道他不想在佳节时与家人团聚吗?每当这时,他又说:“人员紧张,名额有限,让给他们。呵呵,再说,我是以店为家”,也许这时,他的笑容里带有一丝让人难以察觉的苦涩!

个人工作事迹简介 在每一个岗位上都有积极分子,在评选时我们叫他们先进个人。那么个人工作事迹简介怎么写呢?下面由为你提供的个人工作事迹简介,希望能帮到你。 个人工作事迹简介(一)我想自己并不比别人聪明,但我可以更加努力,所谓勤能补拙、笨鸟先飞”。这就是同志的信条。从92年参加银行工作至今,正是这股“事事处先”的精神一直激励他、支持他,培养了他良好的思想品质和积极的工作态度。现将一年来该同志先进事迹总结如下: 一、认真做好本职工作。 xx年度16月份,该同志主要在分行稽核部工作,另外兼分行会计出纳部会计检查辅导员。主要工作包括:完成了对各支行财务专项稽核、理财业务专项稽核、对分行机关各部室进行了专项稽核、协同分行办公室实施了劳动工资专项稽核、表外业务专项稽核、分行信贷业务专项稽核、参与总行组织的对深圳地区支行的会计专项稽核、配合人行杭州中支对我分行进行真实性专项检查、实施了内控制度评价稽核、分类分层次监管稽核、分行(管理部)专项现场稽核、支行行长离任稽核、做好计算机xx年问题监管工作,做好贷款到期回收的监控工作和重要业务交接工作、参与分行“营业窗口酒店式”服务组织考评工作、对业务工作中出现的问题及时介入实时监督。作为分行会

计检查辅导员,还负责做好了对支行会计业务的检查辅导工作和季度会计规范化检查工作。 下半年,该同志调分行营业部负责营业厅工作。能够从营业厅实际出发,狠抓基础性工作: 1、优化服务环境,规范服务行为。从服务仪表、服务态度、服务语言、服务规范等方面严格要求员工,推出“每周一星”“服务明星”活动,在分行规范化服务评比中取得第一名; 2、抓岗位培训,强员工素质。推出岗位练兵活动,对员工技能进行强化训练,配合分行快捷工程做好限时服务,在分行技能测试中获总分第一; 3、加强内部管理,建立监督机制,员工自我监督、领导日常监督、社会公开监督紧密结合。同时,建立例会制度总结不足,表扬先进,直接调动员工服务意识和主动意识。 4、把解决认识问题和思想教育贯彻始终,开展形式多样的谈心教育,及时澄清员工的模糊认识,做到上下思想统一,员工步调一致。 5、做好业务培训和规范操作工作,在分行会计规范化检查中成绩居前。 经过半年努力,员工的服务意识和服务质量明显提高,营业环境有效改善,内部管理、规范操作、风险控制得到加强,有效地促进了服务工作的全面提高。同时,在不断改善营业环境、服务设施和推行“微笑服务、两站三声、一双手”为基本内容的柜台服务规范基础上,把抓单纯服务态度转变到以客户为中心、以客户满意为准绳的服务要

简历个人先进事迹范文 在简历上拟写一些先进优秀事迹,对自己的有很大的帮助,今天我们就一起来看看简历个人先进事迹吧! xx,男,1992年2月出生,是×××学校××班学生,现任×××学校轮滑协会会长,入校以来,他严格遵守学院的各项规章制度,他认真踏实,学习勤奋,自觉性强,各科成绩优秀,积极参加各项活动,在思想、学习、生活、个人等方面都取得了较大的进展!受到老师和领导的好评! 他自觉努力学习马列主义、毛泽东思想、邓小平理论和 ___等重要思想,坚持科学发展观,认真贯彻党的十八大精神,不断地扩充自己的思想政治知识,学习党的先进理论知识、坚决拥护共产党的领导,自觉践行社会主义荣辱观。并在各方面起到模范带头作用。通过参加党校培训,认真的学习了各种政治理论知识,在政治思想方面,在思想和行动上严格要求自己,在不断加强自身素养的同时,做好各项工作,全心全意为同学服务。 在学习上,他能做到认真踏实,勤学苦练,刻苦钻研专业知识,努力在学习上取得优良的成绩,积极配合老师的的各项工作的展开,配合校学生会、社团联、团委的工作展开,同时还积极参与院学生会、

分团委、新闻资讯台的各项工作。还曾被评为“军训标兵”,并获得荣誉证书! 在班级里,他是一名优秀学生,和同学相处的十分融洽,互相关心,共同努力,同学们都很喜欢他,信任他。平时,他养成了批评与自我批评的优良作风。他不但能够真诚的指出同学的错误缺点,也能够正确的对待同学的批评和意见。面对同学的误解,他总是一笑而过,不会因为同学的误解和批评而耿耿于怀,而是诚恳的接受,从而不断的提高自己。在生活上他也十分俭朴,从不铺张浪费,也从不乱花一分钱。有时候在学习空闲时间找一些兼职工作,增加一些生活费,为家庭减少一些负担。但是,只要哪个同学在生活上遇到了困难,他都能力尽所能的帮助解决,只要听说有什么捐块活动,他都会竭劲所能的献出自己的一份力量,曾为贫困地方捐出过衣服和英语磁带,他具有良好的道德品质,吃苦耐劳的精神,他是值得学习的好榜样! 20xx年入学天津工业大学,加入了天津工业大学分团委实践部,在一年的工作中,刻苦学习,坚持完成部长分配放入各项任务,多次拉到赞助,为分团委的各项工作提供的资金上的保障,获得“优秀个人奖”,20xx年第一学期参加了大学生创业教育课程,担任班长一职,由于每星期只上一节课,而且学生于不同的学院,不同的班级,在这种情况下,老师分配的工作及任务坚持送到每位同学的耳朵中,得到了同学的信赖和好评。期末完成了创业教育课程,并荣获了奖章,

[中学]个人事迹简介范文 事迹简介 **~男~1991年8月15日出生~现担任****大学09金融一班团支部的组织委员。入校以来严格遵守学校的各项规章制度~做好模范带头作用。平日我妥善处理好班级工作以及和同学之间的关系~在各个方面取得了较大的进展。 1..认真学习~努力工作~。 在学习上我还算是比较系统的学习并掌握了较为扎实的专业知识~虽然在刚刚入校的时候由于没有形成较好的文科思维遇到了很多困难~但是在我坚忍不拔的毅力的驱使下~在第一学期获得了全班第四名的好成绩。在大一下学期获得了全班第二名。在大二第一学期更是获得全班第一名的好成绩~在工作方面~可以用尽心尽力来形容~只从当上了的班上的组织委员~才知道这个职位不是那么的容易~不过总的来说还算做的不错~其中我觉得最好的几次也是最有成就感的事就是春游。一次是上学期去落雁岛春游~作为组织委员我是是身先士卒去考察了下当地的情况~历经千辛万苦终于找到了地方~弄到了说明书和优惠方案。第二次春游是去华农~记得那次是两个班联谊~为了这次联谊的顺利进行~我已经做了一个星期的活动策划了~当时去了之后我发现大家都是各玩各的~甚至有些人直接出去逛了~全然不顾春游的目的~后来我鼓起勇气把家里集结在一起~做了一个非常好远的游戏~在场的人无不不亦乐乎。可以说这次联谊是非常成功的~获得了一致好评: 平时在班上我充当的活动组织者~包括团委和班委方面的工作~ 其中我充当的是班上的联络员~帮忙解决同学的困难。反馈同学的消息~同时让他们能及时知道对自己有用的信息:

我还从事过党组织组织的青年志愿者活动~每次都会全身性地投入于工作~可能是太投的缘故~有一次一不小心把手机弄丢了~对我来说可谓是当头棒喝~但是我还是坚持完成了湖北社区的志愿者工作。 在过去的一个暑假里~我进行了暑期社会实践~可谓是真正的的体会到了生活的艰苦~我打工一个月~每天工作15个小时~在里面由于我是新工~虽然我是大学生~但毕竟人家干的事技术活~还是遭到别人的白眼~在我努力的工作下和不断地摸索中~最终获得了500块钱的工资和大家的不舍。实践过后的我更加坚信我学习的信念~对于来自农村的我~唯有读书这座桥梁~能让我通向成功的彼岸: 2..思想积极上进~不断提到思想素养。 在入校以前~我对什么政治~历史~马克思主义~毛泽东思想~邓小平理论~以及三个代表重要思想可谓是没有一点概念。更重要的是我是完全一点兴趣都没有~但是在深刻的学习了以后~我发现我的观念有了很大的改变~觉得原来学习这些提到素养的知识并不是我想象中的那么无聊~对于马克思的剩余价值理论以及辩证观可谓是佩服的五体投地~现在我还是孜孜不倦的学习着~现在的我较以前的水平有了质的飞跃 3.体育方面 入校以来~总共参加了两次新生杯篮球大赛~从刚开始的青涩到 后来的老练~经历了不少起伏~每次比赛过后我都会发生抽搐现象~可能是我体质的原因~一场比赛过后~小腿都会疼几天~但是我没有被困难吓倒~两次篮球比赛我们分别以09级第一名和全员第三名完美的结束比赛。这些肯定是给我大学生活添上了丰富多彩的一笔~同时也增进了我和同学之间的感情: 4.所在寝室卫生以及评比情况 虽然在寝室文化节里~没有获奖。但我还是尖刺吧寝室收拾到最干净~和同寝室的同学关系搞到最好~在我们的努力下~我们寝室已经多次被评为?优秀寝室?。

优秀员工事迹材料简介 篇一:先进个人事迹简介 先进个人事迹简介 XXX,男,XX年XX月出生,XX年毕业于XXX大学,现任XXX 农机管理员。多年来,他兢兢业业,尽心尽责,工作中勇挑重担,思路开阔、善于学习、勤于思考,虚心向老同志学习业务,默默无闻地奋战在农机工作的第一线。 “在岗就要爱岗,爱岗就要敬业”是他的职业理念。工作中,他一心扑在事业上,兢兢业业,埋头苦于。在工作期间他从不擅自离岗和请假。不管大小事情,他都认认真真地去做,而且做得非常出色。他这种敬业精神受到了单位干部职工的广泛赞誉。办公室是个综合部门,日常事务多,人手少,工作繁忙。他主动承担了文明单位创建、职工教育培训、宣传思想工作等工作。同时,在审核文稿、起草有关材料、处理来信来访、接待来人来客、配合纪检监察等工作方面,他也积极主动,任劳任怨。在他的带动和影响下,办公室的各项工作取得了长足进步。 他常年深入农村和农业生产第一线,每到一处,亲自向农民宣传农机技术和机具,把自己所学的知识毫不保留传授给农民。他经常说,要提高农机科技水平,引导农民使用先进适用的农机新技术、新机具,关键是提高农民的科技意识,这就要靠我们农机工作者广泛宣传,不

断加大科普宣传力度。他经常组织科技人员利用现场会等时机,对农民进行培训。每年组织的送科技下乡活动都在5次以上,技术讲座2以上,发放资料100余份。受教育人数近200人次。 多年来,他为了铸造自己的事业,摸爬滚打,苦干实干、无私奉献,他凭着对工作高度负责的态度和执着敬业的精神,深深的感染和激励着身边的每一位同志,起到了模范带头作用。他只是一名普通的农机管理员,他的事迹也并非惊天动地,但平凡孕育高尚、细小昭示博大,他把对农机事业的一片赤诚融于他的行动,在平凡的工作岗位上,做出了卓越的成绩,在他的身后,留下的是一串串坚实而闪光的足迹。篇二:20XX年前台优秀员工先进事迹简介 优秀员工XXX先进事迹简介 XXX,前厅部前台接待。20XX年8月15日入职至今,努力工作,把每一步都走的踏踏实实,并收获了辛勤耕耘的硕果累累。并始终坚持“在其位,谋其政,尽其职,胜其任”的生活,学习和工作方式。20XX年7、8月份,酒店举行的星级服务师考试,考试前努力复习酒店各部门材料必知,熟练前台操作系统,模拟练习客人接待等。在考试中取得了“五星级服务员”头衔。20XX年10月份,由于工作表现与工作努力,在同事与领导投票下,被选为本月“服务明星”。20XX年1月份凌晨,在跟客人办理入住时,通过交谈她细心的发现客人得了感冒,此时也是凌晨 了,她和西餐值班的厨师处借来了姜丝和红糖,从服务中心借了热水壶,为客人熬制了一壶姜汤水送到了房间,客人很是感动,连连表示

主要事迹简介怎么写 主要事迹怎么写?主要事迹范文个人主要事迹范文 个人主要事迹怎么写? 概括而简要地反映一个单位(集体)或个人事迹的材料。简要事迹不一定很短,如果情况多的话,也有几千字的。简要事迹虽然“简要”,但切忌语言空洞,写得像小学生期末鉴定。而应当以事实来说话。简要事迹是对某单位或个人情况概括而简要地反映情况,比如有三个方面很突出,就写三个方面,只是写某一方面时,要把主要事迹突出出来。 简要事迹一般来说,至少要包括两个方面的内容。一是基本情况。简要事迹开头,往往要用一段文字来表述一些基本情况。如写一个单位的简要事迹,应包括这个单位的人员、承担的任务以及一段时间以来取得的主要成绩。如写个人的简要事迹,应包括该同志的性别、出生年月、参加工作时间、籍贯、民族、文化程度以及何时起任现职和主要成绩。这样上级组织在看了材料的开头,就会对这个单位或个人有一个基本印象。二是主要特点。这是简要事

迹的主体部分,最突出的事例有几个方面就写成几块,并按照一定的逻辑关系进行排列,把同类的事例排在一起,一个方面通常由一个自然段或几个自然段组成。 写作时,特别要注意以下四点: 1.用第三人称。就是把所要写的对象,是集体的用“他们”来表述,是个人的称之为“他(她)”。为了避免连续出现几个“他们”或“他(她)”,单位可直接写名称,个人可写其姓名。 2.掌握好时限。无论是单位或个人的简要事迹,都有一个时间跨度,既不要扯得太远,也不要故意混淆时间概念,把过去的事当成现在的事写。这个时间跨度多长,要根据实际情况而定。如上级要某个同志担任乡长以来的情况就写他任乡长以来的事迹;上级要该同志两年来的情况,就写两年来的事迹。当然,有时为了需要,也可适当地写一点超过这个时间的背景情况。 3.用点他人的语言。就是在写简要事迹时,可用些群众的语言或有关人员的语言,这样会给人一种生动、真切的感觉,衬托出写作对象比较高的思想境界。在用他人语言时,可适当加工,但不能造假。

事迹简介 **,男,1991年8月15日出生,现担任****大学09金融一班团支部的组织委员。入校以来严格遵守学校的各项规章制度,做好模范带头作用。平日我妥善处理好班级工作以及和同学之间的关系,在各个方面取得了较大的进展。 1..认真学习,努力工作,。 在学习上我还算是比较系统的学习并掌握了较为扎实的专业知识,虽然在刚刚入校的时候由于没有形成较好的文科思维遇到了很多困难,但是在我坚忍不拔的毅力的驱使下,在第一学期获得了全班第四名的好成绩。在大一下学期获得了全班第二名。在大二第一学期更是获得全班第一名的好成绩,在工作方面,可以用尽心尽力来形容,只从当上了的班上的组织委员,才知道这个职位不是那么的容易,不过总的来说还算做的不错,其中我觉得最好的几次也是最有成就感的事就是春游。一次是上学期去落雁岛春游,作为组织委员我是是身先士卒去考察了下当地的情况,历经千辛万苦终于找到了地方,弄到了说明书和优惠方案。第二次春游是去华农,记得那次是两个班联谊,为了这次联谊的顺利进行,我已经做了一个星期的活动策划了,当时去了之后我发现大家都是各玩各的,甚至有些人直接出去逛了,全然不顾春游的目的,后来我鼓起勇气把家里集结在一起,做了一个非常好远的游戏,在场的人无不不亦乐乎。可以说这次联谊是非常成功的,获得了一致好评! 平时在班上我充当的活动组织者,包括团委和班委方面的工作,

其中我充当的是班上的联络员,帮忙解决同学的困难。反馈同学的消息,同时让他们能及时知道对自己有用的信息! 我还从事过党组织组织的青年志愿者活动,每次都会全身性地投入于工作,可能是太投的缘故,有一次一不小心把手机弄丢了,对我来说可谓是当头棒喝,但是我还是坚持完成了湖北社区的志愿者工作。 在过去的一个暑假里,我进行了暑期社会实践,可谓是真正的的体会到了生活的艰苦,我打工一个月,每天工作15个小时,在里面由于我是新工,虽然我是大学生,但毕竟人家干的事技术活,还是遭到别人的白眼,在我努力的工作下和不断地摸索中,最终获得了500块钱的工资和大家的不舍。实践过后的我更加坚信我学习的信念,对于来自农村的我,唯有读书这座桥梁,能让我通向成功的彼岸!2..思想积极上进,不断提到思想素养。 在入校以前,我对什么政治,历史,马克思主义,毛泽东思想,邓小平理论,以及三个代表重要思想可谓是没有一点概念。更重要的是我是完全一点兴趣都没有,但是在深刻的学习了以后,我发现我的观念有了很大的改变,觉得原来学习这些提到素养的知识并不是我想象中的那么无聊,对于马克思的剩余价值理论以及辩证观可谓是佩服的五体投地,现在我还是孜孜不倦的学习着,现在的我较以前的水平有了质的飞跃 3.体育方面 入校以来,总共参加了两次新生杯篮球大赛,从刚开始的青涩到

---------------------------------------------------------------范文最新推荐------------------------------------------------------ 先进事迹简介怎么写 要拟定恰当的标题。 先进事迹材料的标题,有两部分内容必不可少,一是要写明先进个人姓名和先进集体的名称,使人一眼便看出是哪个人或哪个集体、哪个单位的先进事迹。二是要概括标明先进事迹的主要内容或材料的用途。例如《王鬃同志端正党风的先进事迹》、《关于评选张鬃同志为全国新长征突击手的材料》、《关于评选鬃处党支部为省直机关先进党支部的材料》等。 然后,要写先进人物或先进集体的主要事迹。 这部分内容是全篇材料的主体,要下功夫写好,关键是要写得既具体,又不繁琐;既概括,又不抽象;既生动形象,又很实在。总之,就是要写得很有说服力,让人一看便可得出够得上先进的结论。比如,写一位端正党风先进人物的事迹材料,就应当着重写这位同志在发扬党的优良传统和作风方面都有哪些突出的先进事迹,在同不正之风作斗争中有哪些突出的表现。又如,写一位搞改革的先进人物的事迹材料,就应当着力写这位同志是从哪些方面进行改革的,已经取得了哪些突出的成果,特别是改革前后的。经济效益或社会效益都有了哪些明显的变化。在写这些先进事迹时,无论是先进个人还是先进集体的,都应选取那些具有代表性的具体事实来说明。必要时还可运用一些数字,以增强先进事迹材料的说服力。 1 / 15

最后,是先进事迹材料的署名。 一般说,整理先进个人和先进集体的材料,都是以本级组织或上级组织的名义;是代表组织意见的。因此,材料整理完后,应经有关领导同志审定,以相应一级组织正式署名上报。这类材料不宜以个人名义署名。 先进事迹范文(一) 中国共产党的优秀党员、党的优秀民族干部,内蒙古自治区党委常委、呼和浩特市委书记牛玉儒同志,因病医治无效,于2004年8月14日4时30分在北京不幸逝世,享年51岁。 牛玉儒同志1952年11月出生于内蒙古自治区通辽市一个革命干部家庭。1970年5月在通辽县农村插队锻炼。 1971年12月在哲里木盟盟委办公室工作。1975年11月加入中国共产党。1977年3月担任通辽县莫力庙公社党委书记。1978年2月在中央民族学院干部培训班政治专业学习。1979年7月在内蒙古自治区哲里木盟委员会组织部工作。1980年5月调内蒙古自治区政府办公厅工作。 1983年3月在内蒙古自治区纪律检查委员会先后任秘书、秘书长、常委,其间于1987年9月至1989年11月在内蒙古管理干部学院行政管理专业学习。1989年11月开始,先后任内蒙古自治区政府副秘书长兼办公厅主任、政府党组成员,秘书长兼办公厅党组书记。1996年11月任内蒙古自治区包头市委副书记、市长。2001年2月任内蒙古自治区副主席、政府党组成员。2003年4月任内蒙古自治区党委常委、呼和浩特市委书记。牛玉儒同志是第九届全国人民代表大会代表。