Mol Genet Genomics (2008) 280:187–198

DOI 10.1007/s00438-008-0355-0

ORIGINAL PAPER

Recent duplications dominate NBS-encoding gene expansion in two woody species

Sihai Yang · Xiaohui Zhang · Jia-Xing Yue ·

Dacheng Tian · Jian-Qun Chen

Received: 14 January 2008 / Accepted: 1 June 2008 / Published online: 19 June 2008

? Springer-Verlag 2008

Abstract Most disease resistance genes in plants encode NBS-LRR proteins. However, in woody species, little is known about the evolutionary history of these genes. Here, we identi W ed 459 and 330 respective NBS-LRRs in grape-vine and poplar genomes. We subsequently investigated protein motif composition, phylogenetic relationships and physical locations. We found signi W cant excesses of recent duplications in perennial species, compared with those of annuals, represented by rice and Arabidopsis. Conse-quently, we observed higher nucleotide identity among par-alogs and a higher percentage of NBS-encoding genes positioned in numerous clusters in the grapevine and pop-lar. These results suggested that recent tandem duplication played a major role in NBS-encoding gene expansion in perennial species. These duplication events, together with a higher probability of recombination revealed in this study, could compensate for the longer generation time in woody perennial species e.g. duplication and recombination could serve to generate novel resistance speci W cities. In addition,we observed extensive species-speci W c expansion in TIR-NBS-encoding genes. Non-TIR-NBS-encoding genes were poly- or paraphyletic, i.e. genes from three or more plant species were nested in di V erent clades, suggesting di V erent evolutionary patterns between these two gene types. Keywords NBS-LRR genes · Disease resistance genes · Evolution · Grapevine · Poplar

Introduction

Numerous disease resistance genes (R-genes) conferring resistance to a diverse spectrum of pathogens, including bacteria, fungi, oomycetes, viruses, and nematodes, have been isolated from a wide range of plant species (Dangl and Jones 2001; Meyers et al. 2003; McHale et al. 2006). The NBS-LRR gene, which contain a nucleotide-binding site (NBS) and leucine-rich repeats (LRRs), is the largest class of R-genes. These proteins have been shown to function as intracellular immune receptors that recognize, directly or indirectly, speci W c pathogen e V ectors encoded by aviru-lence (Avr) genes (Bent and Mackey 2007). For example, in solanaceous plants, four R-genes were found to detect Avr proteins directly, while four others recognized the Avr pro-tein indirectly, which exerted e V ects on a target protein (van Ooijen et al. 2007).

The deduced NBS-LRR proteins can be divided into two subfamilies, TIR-NBS-LRR (TNL) and non-TNL based on their N-terminal features. TNLs possess a domain with sim-ilarity to both the intracellular signaling domains of Dro-sophila Toll and the mammalian Interleukin-1 receptor (TIR). Non-TNL often have a putative N-terminal coil-coil (CC) and are thus designated CNLs (Dangl and Jones 2001). The highly conserved NBS domain in the R proteins

Sihai Yang and Xiaohui Zhang contributed equally to this work. Communicated by A. Tyagi.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00438-008-0355-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

S. Yang · X. Zhang · J.-X. Yue · D. Tian (&) · J.-Q. Chen (&) State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Department of Biology, Nanjing University,

210093 Nanjing, China

e-mail: dtian@https://www.doczj.com/doc/dd4327277.html,

J.-Q. Chen

e-mail: chenjq@https://www.doczj.com/doc/dd4327277.html,

has been demonstrated to be able to bind and hydrolyze ATP and GTP and this domain is also found in other pro-karyotic and eukaryotic proteins (Meyers et al. 1999). Di V erent from NBS domain, the LRR motif is typically involved in protein-protein interactions and responsible for recognition speci W city (Dangl and Jones 2001).

Gene encoding NBS-LRR proteins comprise one of the largest gene families in plant genomes, with a total of 149 and 480 members identi W ed in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa, respectively (Meyers et al. 2003; Zhou et al. 2004; Yang et al. 2006). In addition, CNLs are found widely in angiosperm (Cannon et al. 2002). In rice, three atypical “TNs” (TNL but lacking an LRR domain) have been characterized, which di V er substantially from typical TNL genes (Bai et al. 2002). These data suggested that R-gene arsenals have diverged substantially between mono-cot and dicot lineages over the course of evolution. More recently, approximately 330 NBS-encoding genes were detected in incomplete genome sequences (?58% of the whole genome) of Medicago truncatula (Ameline-Torreg-rosa et al. 2008). In addition, over 1,600 NBS sequences have been ampli W ed from a diverse array of plant species using degenerate PCR primers (Cannon et al. 2002; McHale et al. 2006). Furthermore, results of nucleotide polymorphism analyses have demonstrated extremely high levels of inter- and intraspeci W c variation, which presum-ably evolved rapidly in response to pathogen population changes (Ding et al. 2007a, b; Shen et al. 2006; Yang et al. 2007).

Most NBS-LRR genes are unevenly distributed in plant genomes and existing mainly as multi-gene clusters (Meyers et al. 2003; Zhou et al. 2004; Ameline-Torregrosa et al. 2008). In the rice genome, 24.98% R-like genes are present on chromosome 11, with most located in several large clusters. These genes were possibly originated by tan-dem duplication and subsequent divergence under the selective pressure of rice pathogens (Rice Chromosomes 11 and 12 Sequencing Consortia 2005). The clustered distribu-tion of R-genes provides a reservoir of genetic variation from which new speci W cities to pathogens can evolve via gene duplication, unequal crossing-over, ectopic recombi-nation or diversifying selection (Michelmore and Meyers 1998). However, the speci W c evolutionary routes of NBS-encoding genes still remain elusive. The complete genome sequences of grapevine (Vitis vinifera), poplar (Populus trichocarpa), Arabidopsis(Arabidopsis thaliana) and rice (Oryza sativa) provide an opportunity to conduct compara-tive genomic analyses of NBS-encoding genes (Arabidop-sis Genome Initiative 2000; International Rice Genome Sequencing Project 2005; Jaillon et al. 2007; Tuskan et al. 2006). In this study, we W rst identi W ed 535 and 416 respec-tive NBS-encoding genes residing in grapevine and poplar genomes. We subsequently analyzed their evolution and genomic organization. Di V erent patterns of TIR versus non-TIR-NBS-encoding gene evolution were observed. This analysis also suggested that recent tandem duplication could play a major role in the expansion of NBS-encoding genes in the two woody species.

Materials and methods

Identi W cation of NBS-encoding genes

Grapevine (Vitis vinifera) assembly and annotation V1.0 were downloaded from https://www.doczj.com/doc/dd4327277.html,s.fr/externe/ English/Projets/Projet_ML/index.html. Poplar (Populus trichocarpa) genome sequences V1.1 were found in http:// https://www.doczj.com/doc/dd4327277.html,/poplar. The same methods (as in Zhou et al. 2004; Yang et al. 2006) were employed to identify NBS-encoding genes in grapevine and poplar. Firstly, amino acid sequence of NB-ARC domain (Pfam: PF00931) was adopted as a query in BLASTP searches for possible homologs encoded in grapevine and poplar genomes. The threshold expectation value was set to 10?4, a value deter-mined empirically to W lter out most of the spurious hits. Secondly, the NBS domain was determined by Pfam ver-sion 22.0 (https://www.doczj.com/doc/dd4327277.html,/). Then, the nucleotide sequences of candidate NBS genes were used as queries to W nd homologs in grapevine or poplar genomes by BLASTn searches. This step was crucial to W nd the maximum number of candidate genes. All new BLAST hits in the genomes, together with X ank regions of 5,000–10,000 bp at both sides, were annotated using the gene-W nding programs FGENESH (https://www.doczj.com/doc/dd4327277.html,/) and GENSCAN (https://www.doczj.com/doc/dd4327277.html,/genescan.html/ ) to obtain information on complete open reading frames (ORFs).

To exclude potentially redundant candidate NBS genes, all sequences were orientated by BLASTn, and sequences located in the same location were eliminated. All non-redundant candidate NBS genes were surveyed to further verify whether they encoded TIR, CC, NBS, or LRR motifs using the Pfam database (https://www.doczj.com/doc/dd4327277.html,/), SMART protein motif analyses (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/), MEME (Multiple Expectation Maximization for Motif Elicitation, Bailey and Elkan 2005), and COILS with a threshold of 0.9 to speci W cally detect CC domains (Lupas et al. 1991). This detailed information on protein motifs and domains was used to classify the NBS-encoding genes into subgroups (Table1).

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis

Multiple alignments of amino acid sequences were per-formed using ClustalW with default options (Thompson et al. 1994). The alignments were carried out using the

NBS region, based on the Pfam results. Phylogenetic trees were constructed based on the Bootstrap neighbor-joining (NJ) method with a Kimura 2-parameter model by MEGA v4.0 (Tamura et al. 2007). The stability of internal nodes was assessed by bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replicates.

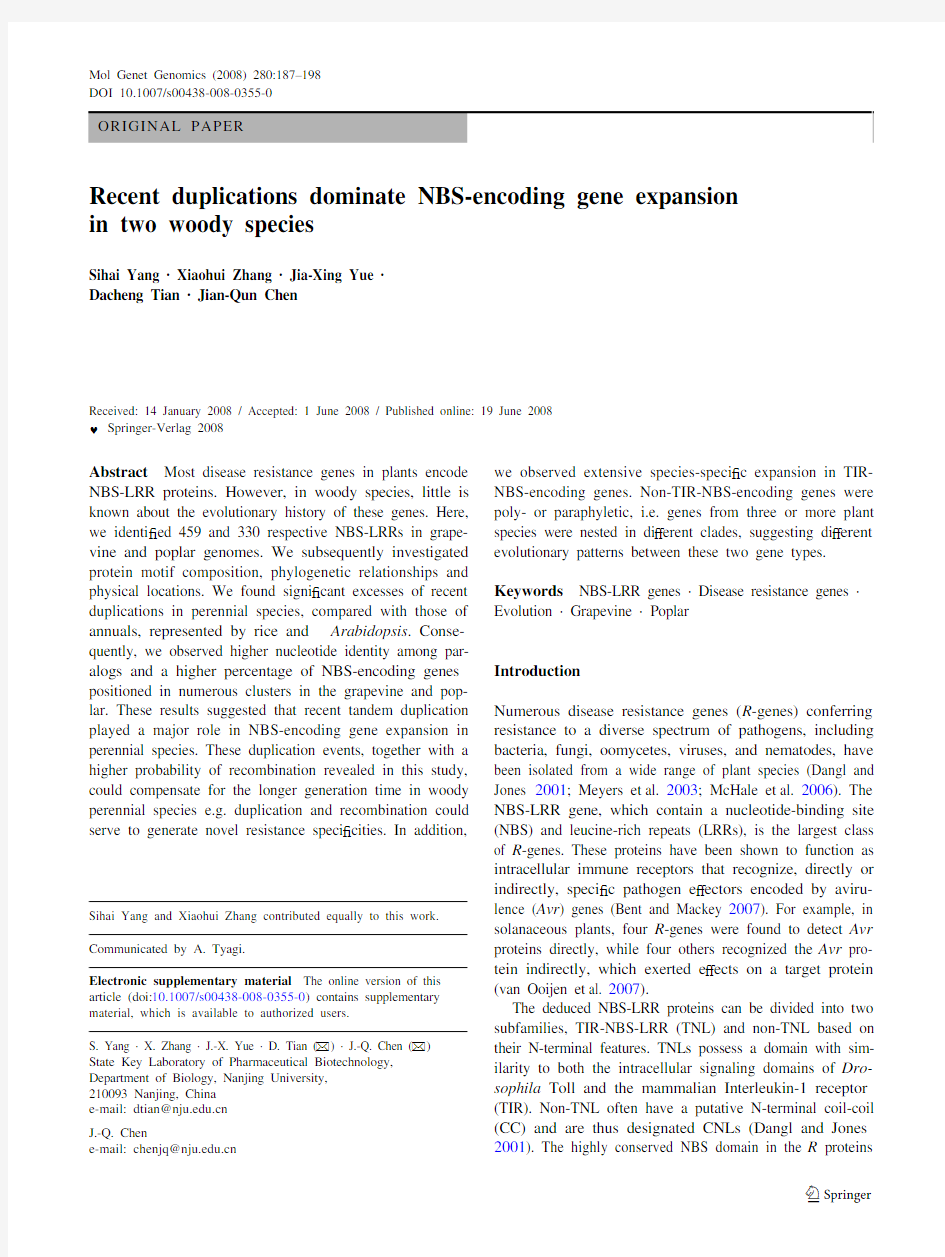

The number of nonsynonymous substitutions per nonsyn-onymous site and the number of synonymous substitution per synonymous site were denoted by K a and Ks respec-tively. In order to detect the mode of selection, we evaluated the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous nucleotide sub-stitutions (K a/K s) among paralogs. Protein sequences of par-alogs were initially aligned by ClustalW, and the resulting alignments were then used to guide the aligning of nucleo-tide coding sequences (CDSs) using MEGA. The K a and K s were calculated by DnaSP v4.0 (Rozas et al. 2003) based on Nei and Gojobori (1986). Generally, a K a/K s ratio >1 indi-cates positive selection, the ratio <1 indicating negative or purifying selection, while the ratio 1 indicating neutral evo-lution. Full-length CDS sequences were used to infer the information of gene duplication. The time of duplication event for each node in phylogenetic trees was determined by average K s of the node, which was calculated by taking the arithmetic mean of all left-right branch combinations (Fig.1). For example, K s for node AII was determined by the sum of the K s of sequence pairs A&C and B&C divided by the number of pairs; K s for node BIII was determined by the sum of the K s of sequence pairs A&C, A&D, B&C and B&D divided by the number of pairs (Fig.1).

Nucleotide divergence among paralogs was estimated by with the Jukes and Cantor correction (Lynch and Crease 1990) using DnaSP v4.0 (Rozas et al. 2003). A gene cluster was de W ned as a region in which two neighboring homolo-gous genes were < 200 kb apart (Holub 2001). Sequence exchange between duplicates was investigated by the pro-gram GENECONV 1.81 (https://www.doczj.com/doc/dd4327277.html,/?sawyer/geneconv/). The default setting with 10,000 permu-tations was used for the analysis. The statistical signi W cance of gene conversion events were de W ned as a global permu-tation P value of <0.05.

Results

Total number of NBS-encoding genes in grapevine

and poplar

Five hundred thirty-W ve and 416 NBS-encoding genes, including 459 and 330 NBS-LRR-encoding genes, were identi W ed in grapevine and poplar, respectively (Table1). Among the 459 NBS-LRR grapevine genes, 97 were identi-W ed as TNL resistance genes, including TNL?, TCNL, TNLT, TNLTN, and TNLTNL (Table1) and 362 non-TNLs, including CNL, CNNL, CNLNL, XNL, and NL. In addition, 76 NBS type genes, which lacked LRR domains, were detected containing CN, TN and XN genes (Table1). In the poplar genome, 78 and 252 respective NBS-encoding

Table1The number of genes that encode domains similar to NBS genes in four plant genomes Predicted protein domains Letter code Grapevine Poplar Arabidopsis a Rice b

Total NBS-encoding genes535416174519 NBS-LRR type genes

TIR-NBS-LRR TNL

TIR-NBS-LRR TNL?9073930 TIR-CC-NBS-LRR TCNL1000 TIR-NBS-LRR-TIR TNLT3400 TIR-NBS-LRR-TIR-NBS TNLTN1100 TIR-NBS-LRR-TIR-NBS-LRR TNLTNL2000 Non-TIR-NBS-LRR Non-TNL

CC-NBS-LRR CNL20011951159 CC-NBS-NBS-LRR CNNL2101 CC-NBS-LRR-NBS-LRR CNLNL1000 X-NBS-LRR XNL1471320304 NBS CC-LRR NL12030 Total459330147464 NBS type genes

CC-NBS CN261457 X-NBS XN3662145 TIR-NBS TN1410213 Total76862755 TIR-X type genes TX27108301

CC coiled-coil domain,

LRR leucine-rich repeat domain, NBS nucleotide-binding site, TIR Toll/interleukin-1-receptor, X some unknown motifs

a Data from Meyers et al. (2003)

b Data from Zhou et al. (2004) and Yang et al. (2006)

genes were classi W ed as TNLs and non-TNLs. Eighty-six NBS genes were found, which lacked the LRR domain (Table1).

Approximately 30,434, 45,555, 27,000 and 37,544 pro-tein-coding genes were estimated in the full sequenced grapevine, poplar, Arabidopsis and rice genomes, respec-tively (Jaillon et al. 2007; Tuskan et al. 2006; Arabidopsis Genome Initiative 2000; International Rice Genome Sequencing Project 2005). The NBS-LRR genes accounted for approximately 1.51, 0.72, 0.53 and 1.23% of all pre-dicted ORFs in these four species, respectively. Both the absolute number and relative proportion of NBS-LRR genes in grapevine and rice were signi W cantly higher than those in poplar and Arabidopsis genomes (Table1).

The average number of exons detected in NBS-LRR genes was 3.96 in grapevine, 3.72 in rice, 2.35 in poplar and 4.19 in Arabidopsis. These exon estimates were less than that in all predicted genes within each of the four taxa, which was 5.0, 4.9, 4.3 and 5.8 per gene, respectively (Jail-lon et al. 2007; International Rice Genome Sequencing Pro-ject 2005; Tuskan et al. 2006; Arabidopsis Genome Initiative 2000). The average TNL exon numbers were sig-ni W cantly greater than those in non-TNLs (t test, P< 0.001). In grapevine, 7.68 TNL exons were detected vs.

3.22 non-TNLs and 3.5 vs. 2.23 in poplar. This result was consistent with previous studies in Arabidopsis that indi-cated most CNL genes were encoded by a single exon (2.17 on average) and TNLs were encoded by multiple exons (5.25 on average; Meyers et al. 2003).

Organization and phylogeny of NBS-encoding genes

in two woody genomes

Studies in Arabidopsis and rice report an uneven distribu-tion of NBS-encoding genes on chromosomes (Meyers et al. 2003; Zhou et al. 2004). In the present study, based on the location of individual NBS genes on chromosomes (Jaillon et al. 2007; Tuskan et al. 2006), 354 out of 535 grapevine NBS-encoding genes (66.2%) were mapped on 19 chromosomes. The remaining genes were situated on unanchored supercontigs (chromosome(s) unknown). For the 354 anchored NBS genes, 236 (66.7%) were physically located on chromosomes 9, 12, 13 and 18, with 49, 49, 58 and 80 NBS-encoding genes on each respective chromo-some. NBS genes were absent from chromosomes 7 and 10 (Table2; Fig. S1). Similarly, in poplar 43.3% (180 out of 416) of NBS genes were mapped on 19 chromosomes (Table2; Fig. S2); 61.7% (111 out of 180) were found physically localized on chromosomes 1, 2, 3 and 19, including 26, 23, 20 and 42 genes, respectively (Table2; Fig. S2). In addition, two chromosomes lacked NBS-encod-ing genes, e.g. chromosomes 10 and 17.

The majority of NBS-containing genes in the grapevine (83.2%) and the poplar (67.5%) genomes were found in clusters (Tables2 and 3; Fig. S1 and S2). A gene cluster is de W ned as a region in which two neighboring homologous genes are <200 kb apart. In grapevine, 77 clusters, includ-ing 445 NBS genes, were identi W ed (Tables2 and 3). On an average, 5.78 NBS members were detected in a cluster, which could be slightly underestimated due to unanchored sca V old sequences. The largest cluster, comprised of 26 NBS members (14 TNLs, 7 TNs and 5 XNLs), was detected on chromosome 18 (Fig. S1). In poplar, there were 281 NBS genes in 75 clusters (Table2), with an average of 3.75 NBS members per cluster. The largest cluster, contain-ing 19 NBS members (4 TNLs, 2 CNLs, 9 XNLs and 4 XNs), was found on chromosome 19.

Previous studies have shown that phylogenies con-structed from the NBS domain were robust and distin-guished TNL and non-TNL subfamilies (Meyers et al. 1999; Meyers et al. 2002). These two distinct groups (Boot-strap value >98%) were also identi W ed in the phylogenetic reconstruction using grapevine and poplar conserved NBS protein sequences (Figs. S3 and S4). In grapevine, the

Fig.

1Schematic diagram average K s calculations at each node, each

node represents one duplication event. The K s value for each node was calculated by taking the arithmetic mean of all left-right branch com-binations. For example, K s for node AII was determined by the sum of K s sequence pairs A&C and B&C divided by the number of pairs;K s for node AIII was determined by the sum of K s sequence pairs A&D, B&D and C&D divided by the number of pairs; K s for node BIII was determined by the sum of K s sequence pairs A&C, A&D, B&C and B&D divided by the number of pairs

TIR-NBS clade included 97 TNLs, 14 TNs, 2 CNLs, 13 XNLs and 1 XN. Interestingly, 2 CNL genes, G_11213 (on unknown chromosome) and G_21959 (on chromosome 18), were found nested in the TIR-NBS clade. G_11213 showed a high nucleotide identity (86%) with a typical TCNL gene (G_38789). Compared to G38789, a 90 amino acid deletion was found at the N-terminal end of G_11213, suggesting a truncation or fusion of domains leading to novel domain compositions. The other CNL gene resided in a cluster con-taining 13 TNLs or TNs members, suggesting TN ancestry.

Table2Distribution of NBS-encoding R-genes on chromo-somes in grapevine and poplar genomes Chromosome Species TNL TN CNL CN XNL XN Clusters

(Gene no.)

Total Tir_X

1Grapevine206011 2 (10)100 Poplar4110335 6 (18)262 2Grapevine0000100 (0)10 Poplar1016042 3 (20)231 3Grapevine005162 1 (10)140 Poplar219053 3 (12)203 4Grapevine0010000 (0)10 Poplar100010 1 (2)21 5Grapevine11120110 4 (25)251 Poplar101011 1 (2)41 6Grapevine204061 4 (12)131 Poplar003020 1 (3)50 7Grapevine0000000 (0)00 Poplar303010 2 (5)71 8Grapevine001010 1 (2)20 Poplar200000 1 (2)20 9Grapevine0032377 6 (45)490 Poplar0000110 (0)20 10Grapevine0000000 (0)00 Poplar0000000 (0)00 11Grapevine004020 1 (3)61 Poplar534131 2 (16)1714 12Grapevine131131137 6 (44)490 Poplar203130 1 (5)90 13Grapevine102732347 (54)580 Poplar404032 2 (5)131 14Grapevine005011 2 (5)70 Poplar0010000 (0)10 15Grapevine006241 3 (10)130 Poplar011010 1 (2)30 16Grapevine0000200 (0)20 Poplar0000100 (0)11 17Grapevine003020 1 (3)50 Poplar0000000 (0)00 18Grapevine548401318 (76)8011 Poplar101010 1 (2)31 19Grapevine0011161 4 (16)192 Poplar110202277 (41)4211 Chro-Unknown Grapevine1447914601027 (130)18111 Poplar414629804043 (146)23671 Total Grapevine9714203261593677 (445)53527 Poplar7810120141326275 (281)416108

In addition, numerous XNLs or XNs were located in the TIR-NBS clade, indicating that all the XNL or XN genes might be TIR-NBS-related, although no TIR domain was detected.

In grapevine, 80.4% of TNLs and 71.4% of TNs were located on chromosomes 5, 12 and 18 (Table2; Fig. S1). Chromosome 18 was nearly an exclusive TIR-NBS chro-mosome (Table2), with 55.7% (54 out of 97) of the TNLs and 57.1% (8 out of 14) of the TNs were detected on this chromosome. Furthermore, 14 NBS genes, 13 XNLs and 1 XN, were found on this chromosome. These genes were positioned in the TIR-NBS clade and therefore were most likely TIR-related (Fig. S3). The remaining four genes on chromosome 18 were CNLs (Table2). The phylogenetic analysis suggested that G_11213 (as mentioned above) evolved from a TNL gene with a TIR domain deletion. Two of the other three CNLs, G_01807 and G_21959, were sin-gle genes located in heterogeneous clusters mixing with TIR-NBS genes. The remaining 1 CNL had a high nucleo-tide identity with a large NBS gene family (identity ranging from 77 to 95% and 87% on average) that included other 8 CNL and XNL members located on chromosome 5, sug-gesting that this gene might translocate to chromosome 18 from chromosome 5 after gene duplication.

The poplar phylogeny (Fig. S4) shows the TIR-NBS clade were composed of 78 TNLs, 10 TNs, 18 XNLs and 15 XNs. The non-TIR-NBS clade exhibited an intriguing phylogenetic subclade (bootstrap value >95%), which included 59 members of 45 XNLs, 3 CNLs and 11 XNs. In this subclade, 45 members carried an N-terminal BED binding zinc W nger domain (Zf_BED domain; Pfam: PF02892; Tuskan et al. 2006), containing 35 Zf_BED-NBS-LRRs (BNL), 2 Zf_BED-CC-NBS-LRRs (BCNL) and 8 Zf_BED-NBS lacking LRR (BN). However, none of the Zf_BED-NBS genes could be detected outside the pop-lar clade, with the exception one BNL (Xa1) in rice.

Another domain (Pfam: PF05659) shared by the broad-spectrum resistance protein RPW8 and its family members in Brassicaceae (Xiao et al. 2001, 2004) was detected in a few NBS genes from grapevine and poplar (Figs. S3 and S4). Five CNLs or CNs (G_08450, G_03901, G_10062, G_04842, and G_12615) in grapevine and one XNL (P_563015) in poplar were found carrying this domain. This result suggested that NBS-LRR novel domain compo-sitions might occur by the fusion of CNL and RPW8 domains. Therefore, the RPW8 gene exhibiting broad-spec-trum mildew resistance in Arabidopsis could have ancient origins and have co-evolved with or possess functional requirements to NBS-LRR genes.

NBS gene duplication

Based on the NBS-LRR gene analysis in Arabidopsis, results suggested that both tandem and large-scale block duplication contributed to the expansion of this gene group (Leister 2004). To identify duplicated gene pairs, we de W-ned a gene family according to the following criteria (Zhou et al. 2004): (1) the alignable nucleotide sequence covered >70% of the longer aligned gene, and (2) the amino acid identity between the sequences was >70%. Ninety-four and 61 NBS gene families were identi W ed in grapevine and pop-lar, including 416 (77.8%) and 325 (78.1%) respective NBS genes. The percentage of NBS genes in multi-gene families (two or more members in a family) of the two woody spe-cies was signi W cantly higher than those (47.3 and 53.7%) in the Arabidopsis and rice genomes (Table3). The average number of NBS members per multi-gene family was 4.43 (ranging from 2 to 10) and 5.33 (ranging from 2 to 23) in grapevine and poplar, respectively. Furthermore, the size of the members was signi W cantly larger than those (3.24 and 3.00) in Arabidopsis and rice (Table3). This analysis revealed more duplication in the genomes and the multi-gene families of grapevine and poplar.

To distinguish recent duplications of NBS genes in plant genomes, we employed a more stringent criteria for de W n-ing a multi-gene family, e.g. an amino acid identity >80%. Under this rule, 23.4 and 11.4% of the NBS genes belonged to multi-gene families in Arabidopsis and rice, respectively

Table3Organization of NBS-encoding R-genes in the four plant genomes Organization Grapevine Poplar Arabidopsis Rice

Single-genes119 (172)91 (106)93 (134)240 (460) Multi-genes416 (363)325 (310)81 (40)279 (59) Gene family no.94 (102)61 (64)25 (15)93 (24) Maximal members of a family13 (10)23 (17)7 (4)10 (3) Average members per family 4.43 (3.56) 5.33 (4.84) 3.24 (2.67) 3.00 (2.46) Singleton genes9013546157 Clustered genes445281125362 Cluster no.777539104 Maximal members of a cluster26191111 Average members per cluster 5.78 3.75 3.21 3.48

A multi-gene family was de W ned as genes within >70% (or >80%) amino acid identify

(Table 3). However, 67.9 and 74.5% of the respective multi-genes were identi W ed in grapevine and poplar, com-parable to the percentages generated with a 70% amino acid identity criterion. These results suggested recent duplica-tions were common in the two perennial species and the NBS phylogenetic trees con W rmed the recent duplications.Short branches from the terminal nodes were more frequent in grapevine and poplar than those in Arabidopsis and rice (Fig. S5).

The time of duplication events was estimated by the average K s at each node in the phylogenetic tree. We con-structed phylogenetic trees using full-length protein sequences from each genome, and divided them down into many smaller phylogenetic units using a >70% amino acid identity. In each phylogenetic unit, every node represented one duplication event (Fig.1). The average K s of each node was calculated by taking the arithmetic mean of all left-right branch combinations (Fig.1). K s was considered as the time proxy for duplication event, and the frequency dis-tributions of individual K s values re X ected the relative time of genome duplications. A quite di V erent individual K s dis-tribution was revealed between perennial and annual spe-cies (Fig.2). Compared with both Arabidopsis and rice

genomes, a higher proportion of young duplicates (the smallest K s classes) were present in grapevine and poplar,indicating recent expansion. Additional analyses indicated that 91.8% of NBS multi-genes and all duplicates with K s <0.1 were located in tandem clusters in grapevine. In poplar,the proportion of those genes within tandem clusters was 72.9 or 84.6%, respectively. The clustered locations of young duplicates provided additional evidence that recent tandem duplication, but not ancient large-scale duplication played the major role in NBS gene expansion in the two perennial species.

TIR and non-TIR NBS-encoding genes evolution

Phylogeny reconstruction was employed to estimate evolu-tionary patterns of TIR- and non-TIR-NBS-encoding genes using only conserved NBS domains of the perennial and annual species (Fig. S5). Both TIR- and non-TIR-group were identi W ed in all genes (Fig. S5), therefore we subse-quently constructed separate phylogenies for the two sub-groups (Figs.3 and 4).

The analysis revealed di V erent evolutionary patterns of TIR- and non-TIR-NBS-encoding genes. The TIR-NBS

Fig.2

The frequency distribu-tion of relative K s nodes in the four plant genomes. a grapevine; b poplar; c rice; d Arabidopsis

phylogenetic tree was divided into four major clades sup-ported by branch lengths and bootstrap values (>80%;Fig.3). Clade I was largely a woody-speci W c clade, with grapevine-speci W c subclades Ia and Ic and poplar-speci W c subclades Ib and Id. However, subclade Ib also contained three TNLs from Arabidopsis . Clade II was an Arabidop-sis -speci W c clade including two distinct subclades. Clade III was also comprised of two distinct subclades but was repre-sented by genes from all three dicot species. Clade IV was represented by three atypical TNs from rice (Bai et al.2002) and was therefore considered as the outgroup. The phylogenetic distribution in this tree exhibited a lineage-speci W c expansion in the TIR-type NBS genes, suggesting these genes might be traced to a small number of species-speci W c progenitors.

In contrast, the non-TIR-NBS clades contained NBS genes from at least two or more species (Fig.4). Neverthe-less, three distinct species-speci W c clades could be detected.Subclade A and B were rice-speci W c with 106 and 181 NBS genes, and subclade C was a Zf_BED-NBS poplar speci W c

Fig.3

Phylogenetic tree based on NBS domains from TIR-type NBS genes. Green (grapevine), Blue (poplar), Red (Arabidopsis ), and Black (rice). Subclade I represents a woody-speci W c clade; subclade II repre-sents an Arabidopsis -speci W c clade; subclade III represents a mixed clade; and subclade IV represents a rice-speci W

c clade

Fig.4Phylogenetic tree based on NBS domains from non-TIR-type NBS genes. Green (grapevine), Blue (poplar), Red (Arabidopsis ), and Black (rice). Subclades A and B represent rice-speci W c clades; and subclade C represents a poplar-speci W c BED-NBS clade

clade comprised of 59 members. In general, bootstrap val-ues were low for the non-TIR-NBS analysis, resulting in equivocal results. Results revealed highly divergent non-TIR-NBS genes suggesting a large number of non-speci W c progenitors.

In summary, the topologies of the TIR and non-TIR trees were signi W cantly di V erent. Species-speci W c sequences resulted in short branch lengths in the TIR subfamily. How-ever, multiple sequences resulted in several divergent clad-eds in the non-TIR-NBS subfamily. Furthermore, orthologous genes were readily identi W ed in some non-TIR-NBS clades, while orthologs were not detected in the TIR-NBS phylogeny.

Duplicated NBS gene non-synonymous to synonymous substitution and gene conversion

To explore di V erent selective constrains on duplicated NBS genes, the K s and K a/K s ratio for each pairwise of duplicates were calculated. We excluded the duplicated pairs with a K s < 0.005, which was generally too small to obtain a reliable K a/K s ratio (Zhang et al. 2003). K s was used as a proxy for time and resulted in a signi W cant negative correlation between K a/K s and K s among the most closely related para-logs in both perennial and annual taxa (Fig.5a). These results showed a signi W cantly higher K a/K s in the recent NBS duplicates, and suggested positive selection or relaxa-tion of negative selection occurred soon after duplication events. The RLK gene family demonstrated similar results consistent with the expectation that higher levels of nonsyn-onymous polymorphisms occurred in recently duplicated genes as a result of functional redundancy (Shiu et al. 2004).

The K a/K s ratio varied in di V erent individual NBS-LRR gene domains (Jiang et al. 2007). Our duplicated gene fam-ily analysis in the two woody species con W rmed that the ratio of the LRR domains was signi W cantly higher than the NBS regions (Fig.5 b, c; a two-tailed t test, P < 0.001). The average K a/K s ratios for the LRR and the NBS regions were 0.666 (ranging from 0.22 to 2.78) and 0.552 (0.27–1.46) in grapevine, and 0.733 (0.21–1.49) and 0.518 (0.08–0.96) in poplar, respectively. Relative to the NBS region, a higher K a/K s ratio in the LRR region was detected in grape-vine (72.7% of the families) and poplar (68.1% of the families). In addition, the number of the LRR regions dem-onstrating a K a/K s > 1 exceeded that of NBS regions.

Interestingly, the K a/K s ratio was signi W cantly higher in the non-TIR NBS families than the TIR NBS families (0.664 vs. 0.585 in poplar and 0.673 vs. 0.575 in grapevine; P < 0.05). This observation was consistent with previous studies (Cannon et al. 2002), suggesting stronger diversify-

ing selection in the non-TIR-NBS subfamily.

Gene conversion (and/or unequal crossing-over) events were identi W ed using the GENECONV program. In total,823 and 468 gene conversion events, involving 299 and 187 NBS-encoding genes, were detected in grapevine and poplar, respectively. However, only 143 and 81 gene Fig.

5a The relationships between K a/K s and K s NBS paralogs in grapevine (r2 = 0.97, P < 10?4), poplar (r2 = 0.84, P < 0.005), Arabid-opsis (r2 = 0.93, P < 10?4) and rice (r2 = 0.98, P < 10?4), respectively. The X-axis denotes average K s per unit of 0.1, e.g. K s = 0–0.1, 0.1–0.2, 0.2–0.3 etc. The Y-axis denotes average K a/K s ratios. (b) and (c) K a/K s ratio in di V erent domains in grapevine (b) and poplar (c). Each dot de-notes the average K a/K s ratio in a NBS family. The X-axis and Y-axis denote average K a/K s in the NBS and LRR region, respectively. The line indicates equal K a/K s ratios between NBS and LRR regions

conversion events were detected in Arabidopsis and rice, indicating more sequence exchange between NBS-encod-ing paralogs in perennial species than those in annual plants.

Discussion

Recent tandem duplication in NBS gene expansion

of perennial species

Previous studies identi W ed 174 and 519 NBS-encoding genes, including 149 and 464 NBS-LRR-encoding genes in the Arabidopsis and rice genomes, respectively (Meyers et al. 2003; Zhou et al. 2004; Yang et al. 2006). Gene dupli-cation, including tandem and whole-genome duplication (WGD), has resulted in a substantial increase in gene num-ber. However, NBS-LRR genes in WGD blocks were <10% in Arabidopsis and 0% in rice (Nobuta et al. 2005; Yu et al. 2005). In poplar, WGD resulted in two duplication blocks containing 12 NBS genes. These results were deter-mined by shared phylogenetic clade combinations within multiple physical clusters and by localizations within regions of demonstrated intragenomic synteny (Figs. S2 and S4). WGD NBS blocks were not detected in grapevine (Figs. S1 and S3), indicating that soon after WGD, most duplicated NBS genes were lost. On the other hand, ?91.8, 72.9, 71.2 and 74.6% of NBS family members were detected in tandem clusters of grapevine, poplar, Arabidop-sis and rice, respectively. These results suggested that tan-dem duplication, but not WGD, played a major role in NBS gene expansion in the four plant genomes. Tandemly clus-tered R-genes distribution could provide a reservoir of genetic variation from which new disease resistant speci W c-ities could evolve (Michelmore and Meyers 1998).

However, the duplications shapes in the two woody spe-cies were signi W cantly di V erent from those in rice and Ara-bidopsis based on K s as a time proxy for duplication events (Fig.2). In grapevine and poplar, the recent tandem dupli-cations (K s = 0–0.1) played a substantial role in NBS gene expansion (42.3% in grapevine and 49.4% in poplar). How-ever, a majority of tandem duplicates were found for the K s 0.1–0.4 time frames in Arabidopsis (54.6%) and rice (55.0%). Sequence exchanges between the NBS paralogs also showed that increased gene conversion events (about 3–10-fold larger) were detected in the two perennial species compared with the annual taxa. These results suggested divergent evolutionary patterns between the annual and perennial plants investigated in this study.

The likelihood that a perennial plant will encounter a pathogen or herbivore before reproduction is unequivocal (Tuskan et al. 2006). Compared with the annual plants included in this study, e.g. rice and Arabidopsis, the life history of long-lived perennials limits the plants to catch the evolutionary rates of a microbial or insect pest (Tuskan et al. 2006). Therefore, the recent frequent tandem duplications in woody perennials could result in an increased probability for meiotic and somatic recombination to evolve more novel disease resistance speci W cities (Parniske et al. 1997).

The K a/K s ratio declined sharply over time when using K s as a time proxy in the four plant genomes (Fig.5a), sug-gesting positive selection or relaxation of negative selection on the newly duplicated R-genes. The results also indicated that the majority of duplicated NBS-encoding genes might accumulate degenerative mutations (under a relaxed purify-ing selection or positive selection) for a period of time, fol-lowed by functional specialization (under purifying selection again) by complementary partitioning of ancestral or newly evolved functions.

Unique evolutionary patterns between

TIR- and non-TIR-NBS genes

The conserved NBS domain was used to study the genomic architecture of this gene family. The TIR and non-TIR sequences, including the three atypical rice TNs, were deeply separated in the four plant species (Fig. S5), sug-gesting ancient origins and subsequent divergence between the two NBS genes types. The number of TNLs was similar in Arabidopsis, poplar and grapevine (93, 78 and 97, respectively; Table1). However, the number of non-TIR-NBS-LRR genes varied from 54 in Arabidopsis, 252 in poplar, 362 in grapevine and 464 in rice. Therefore, within each of the four genomes, the total number of R-genes was primarily determined by the variation of non-TNLs.

One of the striking features of the analyses was the topology di V erence between TIR and non-TIR trees. The TIR-NBS results detected “species-speci W c” clades (Fig.3), suggesting that expansion occurred after divergence. Therefore, these types of NBS genes would likely take charge of recognizing “species-speci W c” pathogens. How-ever, in the non-TIR NBS tree, most NBS genes within a clade were from at least two or more species, indicating their ancient origins originated prior to a split between species, even before the monocot and dicot divergence (Fig.4). On the other hand, apparently orthologous genes, which existed in at least three plant genomes, could be detected in no less than 12 clades in the non-TIR NBS phylogeny (Fig.4). However, orthologous genes were not detected in the TIR-NBS subfamily (Fig.3). This unusual variation in the non-TIR-NBS genes suggested these genes play some basic defense roles, possibly as a result of regional adaptation to the biotic environment, owing to balancing selection.

Most “species-speci W c” TIR-NBS genes were concen-trated on one chromosome and typically arranged in one or

a small number of genomic clusters, e.g. on chromosome

18 in grapevine and chromosome 19 in poplar (Table2; Fig. S1 and S2). In particular, 55.7% (54 out of 97) of the TNLs and 57.1% (8 out of 14) of the TNs were localized on grapevine chromosome 18, indicating ongoing tandem duplication for the expansion of this family. These results were consistent with the birth-and-death theory (Michel-more and Meyers 1998). The results also suggested a link between the genome physical organization and the origin of gene structure novelties.

Atypical structures in both non-TIR-NBS and TIR-NBS genes were observed in our study. In the poplar non-TIR-NBS group, an intriguing Zf_BED-NBS clade comprised of 59 members was detected (Fig. S4), which could result from the fusion of an N-terminal BED binding zinc W nger domain with the CC-NBS homolog, and subsequently duplicated. Another unusual domain, RPW8, was identi W ed in a few non-TIR-NBS genes in the two woody species and several TIR-NBS genes with atypical domain arrange-ments, including TNLT, TNLTN, TNLTNL, were also found (Table1). R-genes with similar structure have been characterized in Arabidopsis (Meyers et al. 2002) and Medicago (Ameline-Torregrosa et al. 2008), which were hypothesized to be a fusion of di V erent genes, e.g. a TNTNL gene was a fusion of a TN and TNL gene (Meyers et al. 2002). These W ndings suggested that domain co-option frequently occurred in NBS genes.

Co-evolution between TIR-NBS-encoding genes

and TX genes

Thirty TIR-X genes, which lacked both NBS and LRR domains, were previously identi W ed in Arabidopsis (Meyers et al. 2002). These gene products might be ana-logues of small TIR-adapter proteins that functioned in mammalian innate immune responses (Meyers et al. 2002). In our study, 27, 108 and 1 TXs were identi W ed in grape-vine, poplar and rice, respectively (Table1). Interestingly, approximately 70.4 and 64.5% TXs in grapevine and poplar were found residing in complex clusters, mixed with TN or TNL genes (Fig. S1 and S2). Phylogenetic analysis of the TIR domain showed a pattern similar to that of the TIR-NBS genes, which represented a species-speci W c expan-sion. Furthermore, all TXs were found to reside in mixed phylogenetic clades with TNs or TNLs, except for one unique TX subclade, which included 7 TXs from all four-plant genomes (Fig. S6). The phylogenetic relationship and chromosomal position of TXs to TNs and TNLs suggested TXs were derived from TNs or TNLs and co-evolved. An explanation for the mixed clusters, phylogenetic clades or conserved duplications among TX, TN and TNL genes remains equivocal. However, natural selection may have favored these alleles as functional units.

In the particular TX subclade (Fig. S6), one, one, two and three homologs were detected in rice, grapevine, Ara-bidopsis and poplar, respectively. The average identity between the TX gene in rice (BAF21932) and the six dicot TXs was 55.6% (ranging from 53.7 to 58.4%), suggesting a highly conserved gene indicated by identity values and sim-ilar copy numbers. It was previously hypothesized that TIR encoding genes were lost in grass genomes (Bai et al. 2002). However, here we detected one TIR-X gene (E-value <10?11 from Pfam) in rice. It remains unclear why grass genomes have a greatly reduced set of TIR encoding genes. This could be a lack of TIR encoding gene ampli W cation or gene loss.

Conclusion

To date, the majority of pathogen resistance genes character-ized in plants have provided monogenic dominant resis-tance. Furthermore, most of these genes were allied with the NBS-LRR class of resistance genes and tremendous pro-gress has been made in understanding the evolution and molecular mechanisms of plant NBS-LRR gene-based resis-tance. Compared with annual plants, the long-generation time of woody species prevents a comparable rate of evolu-tionary change relative to microbial or insect pests. How-ever, in this study, we found a signi W cant excess of recent duplications and a higher homologous recombination rate in grapevine and poplar, which could compensate for life his-tory traits and generate novel resistance pro W les. Further-more, an intriguing Zf_BED-NBS-encoding phylogenetic clade, including 59 members, was detected in poplar, indi-cating that some unique R-genes could exist in some species. In addition, TIR-NBS-encoding genes revealed an extensive species-speci W c expansion. Most of the phylogenetic clades in non-TIR-NBS-encoding genes were mixed with genes from at least three species, suggesting di V erent evolutionary patterns between these two gene types. Finally, a signi W cant negative correlation between K a/K s and K s with NBS dupli-cates was observed in grapevine, poplar, Arabidopsis, and rice, indicating that positive selection or relaxation of nega-tive selection occurred soon after duplication.

Acknowledgments This work was supported by the National Natu-ral Science Foundation of China (30570987 and 30470122), Pre-pro-gram for NBRPC (2005CCA02100) and 111 project to D. T., or J-Q. C. References

Ameline-Torregrosa C, Wang BB, O’Bleness MS, Deshpande S, Zhu H, Roe B, Young ND, Cannon SB (2008) Identi W cation and char-acterization of NBS-LRR genes in the model plant medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol 146:5–21

Arabidopsis Genome Initiative (2000) Analysis of the genome sequence of the X owering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408:796–815

Bai J, Pennill LA, Ning J, Lee SW, Ramalingam J, Webb CA, Zhao B, Sun Q, Nelson JC, Leach JE, Hulbert SH (2002) Diversity in nucleotide binding site-leucine-rich repeat genes in cereals. Ge-nome Res 12:1871–1884

Bailey TL, Elkan C (2005) The value of prior knowledge in discover-ing motifs with MEME. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol 3:21–29

Bent AF, Mackey D (2007) Elicitors, e V ectors, and R-genes: the new paradigm and a lifetime supply of questions. Annu Rev Phytopa-thol 45:399–436

Cannon SB, Zhu H, Baumgarten AM, Spangler R, May G, Cook DR, Young ND (2002) Diversity, distribution, and ancient taxonomic relationships within the TIR and non-TIR NBS-LRR resistance gene subfamilies. J Mol Evol 54:548–562

Dangl JL, Jones JD (2001) Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature 411:826–833

Ding J, Araki H, Wang Q, Zhang P, Yang S, Chen JQ, Tian D (2007a) Highly asymmetric rice genomes. BMC Genomics 8:154

Ding J, Zhang W, Jing Z, Chen JQ, Tian D (2007b) Unique pattern of R-gene variation within populations in Arabidopsis. Mol Genet Genomics 277:619–629

Holub EB (2001) The arms race is ancient history in Arabidopsis, the wild X ower. Nat Rev Genet 2:516–527

International Rice Genome Sequencing Project (2005) The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature 436:793–800

Jaillon O, Aury JM, Noel B, Policriti A, Clepet C et al (2007) The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in major angiosperm phyla. Nature 449:463–467

Jiang H, Wang C, Ping L, Tian D, Yang S (2007) Pattern of LRR nucleotide variation in plant resistance genes. Plant Sci 173:253–261 Leister D (2004) Tandem and segmental gene duplication and recom-bination in the evolution of plant disease resistance genes. Trends Genet 20:116–122

Lupas A, Van Dyke M, Stock J (1991) Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science 252:1162–1164

Lynch M, Crease TJ (1990) The analysis of population survey data on DNA sequence variation. Mol Biol Evol 7:377–394

McHale L, Tan X, Koehl P, Michelmore RW (2006) Plant NBS-LRR proteins: adaptable guards. Genome Biol 7:212

Meyers BC, Dickerman AW, Michelmore RW, Sivaramakrishnan S, Sobral BW, Young ND (1999) Plant disease resistance genes en-code members of an ancient and diverse protein family within the nucleotide-binding superfamily. Plant J 20:317–332

Meyers BC, Kozik A, Griego A, Kuang H, Michelmore RW (2003) Genome-wide analysis of NBS-LRR-encoding genes in Arabid-opsis. Plant Cell 15:809–834

Meyers BC, Morgante M, Michelmore RW (2002) TIR-X and TIR-NBS proteins: two new families related to disease resistance TIR-NBS-LRR proteins encoded in Arabidopsis and other plant genomes. Plant J 32:77–92

Michelmore RW, Meyers BC (1998) Clusters of resistance genes in plants evolve by divergent selection and a birth-and-death process. Genome Res 8:1113–1130Nei M, Gojobori T (1986) Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions.

Mol Biol Evol 3:418–426

Nobuta K, Ash W eld T, Kim S, Innes RW (2005) Diversi W cation of non-TIR class NB-LRR genes in relation to whole-genome duplica-tion events in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 18:103–109

Parniske M, Hammond-Kosack KE, Golstein C, Thomas CM, Jones DA, Harrison K, Wul V BB, Jones JD (1997) Novel disease resistance speci W cities result from sequence exchange between tandemly re-peated genes at the Cf–4/9 locus of tomato. Cell 91:821–832 Rice Chromosomes 11 and 12 Sequencing Consortia (2005) The se-quence of rice chromosomes 11 and 12, rich in disease resistance genes and recent gene duplications. BMC Biol 3:20

Rozas J, Sánchez-DelBarrio JC, Messeguer X, Rozas R (2003) DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other meth-ods. Bioinformatics 19:2496–2497

Shen J, Araki H, Chen L, Chen JQ, Tian D (2006) Unique evolutionary mechanism in R-genes under the presence/absence polymorphism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 172:1243–1250

Shiu SH, Karlowski WM, Pan R, Tzeng YH, Mayer KF, Li WH (2004) Comparative analysis of the receptor-like kinase family in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Cell 16:1220–1234

Xiao S, Ellwood S, Calis O, Patrick E, Li T et al (2001) Broad-spec-trum mildew resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana mediated by RPW8. Science 291:118–120

Xiao S, Emerson B, Ratanasut K, Patrick E, O’Neill C et al (2004) Ori-gin and maintenance of a broad-spectrum disease resistance locus in Arabidopsis. Mol Biol Evol 21:1661–1672

Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S (2007) MEGA4: molecular evo-lutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol 24:1596–1599

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ (1994) CLUSTAL W: improv-ing the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-speci W c gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22:4673–4680 Tuskan GA, Difazio S, Jansson S, Bohlmann J, Grigoriev I et al (2006) The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (torr. & gray). Science 313:1596–1604

van Ooijen G, van den Burg HA, Cornelissen BJ, Takken FL (2007) Structure and function of resistance proteins in solanaceous plants. Annu Rev Phytopathol 45:43–72

Yang S, Feng Z, Zhang X, Jiang K, Jin X, Hang Y, Chen JQ, Tian D (2006) Genome-wide investigation on the genetic variations of rice disease resistance genes. Plant Mol Biol 62:181–193

Yang S, Jiang K, Araki H, Ding J, Yang YH, Tian D (2007) A molec-ular isolation mechanism associated with high intra-speci W c diversity in rice. Gene 394:87–95

Yu J, Wang J, Lin W, Li S, Li H et al (2005) The Genomes of Oryza sativa: a history of duplications. PLoS Biol 3:e38

Zhang P, Gu Z, Li WH (2003) Di V erent evolutionary patterns between young duplicate genes in the human genome. Genome Biol 4:R56 Zhou T, Wang Y, Chen JQ, Araki H, Jing Z, Jiang K, Shen J, Tian D (2004) Genome-wide identi W cation of NBS genes in rice reveals signi W cant expansion of divergent non-TIR NBS genes. Mol Genet Genomics 271:402–415

浙大图书馆2018年11月经济类新书推荐 各位老师: 浙大图书馆2018年11月经济类新书书目如下,请参阅。检索网址: https://www.doczj.com/doc/dd4327277.html,:8991/F/?func=file&file_name=hotinfo 图书资料与档案室 2018年11月5日 附:2018年11月经济类新书书目 1.華南農村社會文化研究論文集(作者:庄英章) 2.制度经济学入门(作者:青木昌彦,) 3.四川旅游发展研究中心研究成果集萃, 乡村旅游(作者:宋秋) 4.建设工程项目管理(作者:封金财) 5.海归创业 :海淀留创园20年(作者:李长萍) 6.工程管理专业英语(作者:王凯英) 7.农产品SPS适度保护水平的形成机理与应用策略研究(作者:董银果,) 8.会计信息系统理论与实务 :基于金蝶KIS案例教程(作者:甄阜铭) 9.物流学概论(作者:袁雪妃) 10.大而不倒 :经典版(作者:索尔金) 11.交易金融(作者:林治洪) 12.智能算法在迁移工作流中的应用研究(作者:程秋云) 13.国际服务外包的制度因素分析与制度构建研究(作者:孔祥荣) 14.银行融资结构、银行间竞争与信用风险研究(作者:刘航,) 15.自商业 :未来网络经济新形态(作者:杨健) 16.云南的“西部大开发” :日中共同研究的视点(作者:波平元辰,) 17.The people make the place : dynamic linkages between individuals and organizations /(作者:Smith, D. Brent.) 18.The Oxford handbook of creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship /(作者:Shalley, Christina E.) 19.构建“价值内控体系”的理论与实践(作者:李季泽,) 20.重塑 :信息经济的结构 :the structure of information economy(作者: 张翼成)

第七章:现代生物进化理论 第一节:现代生物进化理论的由来 1.历史上第一个提出比较完整的进化学说的是法国的博物学家拉马克。 拉马克进化学说基本观点:用进废退和获得性遗传,这是生物不断进化的主要原因(先选择后变异,定向变异) (1)地球上所有的生物都不是神造的,而是由更古老的生物进化来的; (2)生物是由低等到高等逐渐进化的; (3)生物的各种适应性特征的形成都是由于用进废退和获得性遗传。 错误观点赏析: (1)抗菌素的使用,病菌向抗药能力增强的方向变异 (2)工业煤烟使浅色桦尺蠖变成黑色 (3)在长期有毒农药的作用下,农田害虫产生了抗药性 (4)北极熊生活在冰天雪地的环境里,它们的身体就产生了定向的白色变异 (5)长颈鹿经常努力伸长颈和前肢去吃树上的叶子,因此颈和前肢都变得很长 注意:变异与环境的关系:变异在环境变化之前已经产生,环境只是起选择作用,不是影响变异的因素,通过环境的选择将生物个体中产生的不定向的有利变异选择出来,其余变异遭到淘汰。例如喷洒杀虫剂只是将抗药性强的个体选择出来,而不是使害虫产生抗药性。 2.达尔文的自然选择学说 自然选择学说的主要内容: 过度繁殖(进化的基础)、生存斗争(进化的动力、外因、条件)、遗传变异(进化的内因)、适者生存(选择的结果) 自然选择:在生存斗争中,适者生存,不适者被淘汰的过程。 意义:科学地解释了生物进化的原因以及生物多样性与适应性,第一次摆脱神学的束缚,走上科学的轨道。 局限:由于受到当时科学发展水平的限制,达尔文不能解释遗传和变异;他对生物进化的解释也仅限于个体水平。达尔文强调物种形成都是渐变的结果,不能很好的解释物种大爆发等现象。 3.现代生物进化理论发展

文献检索一般方法 同学们: 可能你们目前接触到的文献并不多,但以后你的作业和设计很大一部分要求自己查阅文献,期刊,论文来解决(比如说:微生物学,微生物工程工艺原理,酶工程,白酒工艺学,啤酒工艺学,食品安全学,白酒勾兑等)。在四川理工学院我们检索文献的方式不外乎在图书馆找纸质档案和网络检索两种,因为我们通常使用的文献都要求是近三年核心期刊发表的文章,因为只有这些才能反映某个领域目前发展的现状,所以我们一般都偏向于跟新更快的网络搜索,其中又以知网和超星使用最多。下面简单介绍文献检索的一般方法,希望能给大家的学习,包括实验室学习带来一点帮助,有不明白的地方请直接联系我。 1、检索课题名称(中英文) 计算机在中学物理中的应用 The application of computer to physics in middle school 2、分析研究课题 随着计算机技术的不断发展,计算机在教育中的作用愈发突出。在中学物理教育 中,同样可以引入计算的先进技术,改进教育方法,提高教学效率。如今,计算机在 中学物理中的应用主要体现在以下几个方面: 1)计算机技术在课件制作中的应用。 2)计算机在实验仿真中的应用。 3)计算机在教学数据处理中的应用。 根据以上分析,本课题主要是根据计算机在中学物理教学中的几个应用进行相关 材料的查找。 3、检索策略 3.1 检索工具 1)利用“中国知网”查找有关硕士、博士论文。 2)利用“中国期刊全文数据库”查找相关期刊论文。 3)利用“维普科技期刊数据库”查找相关期刊论文。 4)利用“超星数字图书馆”查找相关图书。 5)利用“SpringLink”查找相关论文。

西方图书馆发展史 西方图书馆事业已有4000多年的发展历史,大致可划分为古代、中世纪初期和中期、文艺复兴时期、16~18世纪、1789~1870年和1870~1945年等六个历史时期。 1、古代图书馆的产生是同文字的创造和书写材料的使用是分不开的。随着文献的增多,便开始了如何收集、保存和使用这些文献的问题,图书馆由此应运而生。最古老的图书馆出现于美索不达米亚、中国、古埃及、古希腊等人类文明的最早发源地。 > 美索不达米亚的图书馆考古学家在伊拉克巴格达南部尼普尔的一个寺庙废墟附近发现许多刻有楔形文字的泥板文献,上面刻有祈祷文、神话等等,这是迄今人们所知道的最早的图书馆遗迹之一,该图书馆约存在于公元前30世纪上半叶。在美索不达米亚及其邻近各国也发现了好几批泥板文献。公元前7世纪,亚述王国的国王亚述巴尼拔在首都尼尼微(位于底格里斯河上游)建立了一所很大的皇家图书馆,所藏泥板文献约有2.5万块之多,它们按不同的主题排列,在收藏室的入口处和附近的墙壁上还有这些泥板文献的目录。 > 古代埃及的图书馆考古学家在古埃及的许多地方也发现了图书馆的遗迹,这些图书馆主要收藏泥板文献和纸草文献。新王国第18王朝末的阿门霍特普四世埃赫那顿(公元前1379~前1362在位)在首都阿玛尔那(位于开罗南部)建造了一所皇家图书馆。据古希腊历史学家西西里的狄奥多洛斯编纂的《历史丛书》记载,第19王朝的拉美西斯二世(公元前1304~前1237)在首都底比斯建立了一所图书馆,该馆的入口处有一块刻有"拯救灵魂之处"等字样的石碑。 > 古希腊的图书馆在古希腊,文艺和科学十分繁荣,暨主和学者都拥有藏书。公元前4世纪,各哲学流派在雅典相继产生。柏拉图和亚里士多德都有很大的私人图书馆。据古希腊史地学者斯特拉本说,亚里士多德的大批藏书数易其地,几经沧桑,后来被L.C.苏拉作为战利品带回罗马,政治家M.T.西塞罗有机会享用了这批书。在古希腊的废墟上,还发现了体育学校和医学学校图书馆的遗迹。 > 亚历山大图书馆公元前4世纪,希腊北部的马其顿国王亚历山大征服埃及之后,在尼罗河三角洲的地中海沿岸建立了亚历山大城,托勒密时期该城成为整个地中海地区的最大城市和地中海地区与东方各国的经济和文化交流中心。古代最大的图书馆即是公元前4~前3世纪由托勒密一世祖孙三代建造的亚利山大图书馆。当时正值托勒密王朝鼎盛时期,各国学者云集亚历山大。历代国王又十分热心于搜集图书,致使亚历山大图书馆的馆藏一度达70万卷。历任馆长都是著名学者。馆藏不仅包括希腊的几乎全部重要文献,还包括地中海、中东和古代印度等异族教徒的文献,反映了亚历山大时期崇尚自由的学风。公元前三世纪,该馆馆长卡利马科斯主编的《皮纳克斯》是一部多达120卷的名著提要目录(现存残片)。200多年间,该馆一直是希腊化文化文献的中心。 > 帕加马图书馆在希腊化时期,小亚细亚(今土耳其)帕加马王国的帕加马图书馆可与亚历山大图书馆相媲美。帕加马的历代国王试图使它超过亚历山大图书馆。国王欧墨涅斯二世广泛网罗学者到帕加马,并一度试图劫持亚历山大图书馆馆长。埃及国王为阻止帕加马图书馆的发展,严禁向帕加马输出埃及的纸草。帕加马只好改用羊皮来代替纸草,制成羊皮书。据记载,该馆馆藏曾达20万卷。公元前41年罗马政治家M.安东尼把这些藏书赠给了埃及女王克娄巴特拉七世,由亚历山大图书馆收藏。考古学家发掘了帕加马图书馆遗址,使后人了解到希腊化时代典型的图书馆建筑格局。其馆舍与神庙毗连,入口处立有雅典娜女神像和著名学者碑文。馆内辟有阅览室和书库。图书馆与神庙大殿之间由柱廊连接,读者可在这里讨论问题。 > 古罗马的图书馆古罗马从公元前2世纪开始注意搜集图书。罗马统治者征服各国后,

大学生推荐阅读的100本经典书籍! 追寻生命的意义[奥地利] 弗兰克尔 弗兰克尔是20世纪著名的心理学家,纳粹时期,作为犹太人,他的全家都被关进了奥斯威辛集中营,他的父母、妻子、哥哥,全都死于毒气室中,只有他和妹妹幸存。弗兰克尔不但超越了这炼狱般的痛苦,更将自己的经验与学术结合,开创了意义疗法,替人们找到绝处再生的意义。本书第一部分叙述了弗兰克尔的集中营经历,第二部分阐述了他的“意义疗法”。本书不仅适合于心理学爱好者,也适合面临挑战希望寻找生活意义的人们。 拖延心理学[美] 简?博克/ [美] 莱诺拉?袁 你想要向拖延的恶习开刀吗?这两位加利福尼亚心理学家在她们治疗拖延者的实践中精准地捕捉到了拖延的根本原因。这本书可以帮助读者减轻拖延,更好地享受生活。 宽容[美] 房龙 在宽容与不宽容之间,宗教以血腥和仁慈维护着它几千年的统治,更迭变幻、不滞不流。从众神的黄昏到好奇的人,从宗教裁判所到新天堂,从耶稣基督到布鲁诺……历史席卷一切,也记忆一切。而在这一切之后,始终不离其左右,是利益抑或是人性?这是一部宗教的历史,一部宽容与不宽容的历史,也是一郜人性血腥与进步的历史。文图之间,《宽容》生动地再现了这一历史。 影响力[美] 罗伯特?B?西奥迪尼 影响力是改变他人思想和行动的能力。政治家运用影响力来赢得选举,商人运用影响力来兜售商品,推销员运用影响力诱惑你乖乖地把金钱捧上…人们对影响力的运用存在于社会的每个角落,当一个要求用不同的方式提出来时,你的反应就会不知不觉地从负面抵抗变成积极合作,你为什么会说“是”,这一转变中究竟

蕴涵着怎样的心理策略?《影响力》这本妙趣横生的书可以告诉你。 策略思维迪克西特/奈尔伯夫 耶鲁大学教授奈尔伯夫和普林斯顿大学教授迪克西特的这本著作,用许多活生生的例子,向没有经济学基础的读者展示了博弈论策略思维的道理。人生是一个永不停息的决策过程。从事什么样的工作,怎样打理一宗生意,该和谁结婚,怎样将孩子抚养成人,要不要竞争总裁的位置,都是这类决策的例子。这本书不仅适合对博弈论感兴趣的同学,也同样适合所有希望让生活决策更有条理的同学。 无价[美] 威廉?庞德斯通 为什么免费的巧克力让我们疯狂?为什么百老汇剧场里价格越高的位置卖得越火?为什么100 万美元带来的愉悦感,400万美元才能让它翻倍?为什么议价时,一定要抢先报价,而且一定要狮子大开口?威廉?庞德斯通告诉我们答案:价格只是一场集体幻觉。如果你想了解价格的奥秘,就来读这本书吧! 浅薄[美] 尼古拉斯?卡尔 “谷歌在把我们变傻吗?”当尼古拉斯?卡尔在发表于《大西洋月刊》上赫赫有名的那篇封面文章中提出这个问题的时候,他就开启了人们热切渴望的期盼源泉,让人急于弄清楚互联网是在如何改变我们的。卡尔在本书中阐述了他对互联网时代的看法:互联网会在现代人的心智中打下深深的烙印。这本书会让你看到互联网对我们的影响的另一面。 定位[美] 艾?里斯/杰克?特劳特

高中生物生物的进化知识点归纳 名词: 1、过度繁殖:任何一种生物的繁殖能力都很强,在不太长的时间内能产生大量的后代表现为过度繁殖。 2、自然选择:达尔文把这种适者生存不适者被淘汰的过程叫作自然选择。 3、种群:生活在同一地点的同种生物的一群个体,是生物繁殖的基本单位。个体间彼此交配,通过繁殖将自己的基因传递给后代。 4、基因库:种群全部个体所含的全部基因叫做这个种群的基因库,其中每个个体所含的基因只是基因库的一部分。 5、基因频率:某种基因在整个种群中出现的比例。 6、物种:指分布在一定的自然区域,具有一定的形态结构和生理功能,而且在自然状态下能互相交配,并产生出可育后代的一群生物个体。 7、隔离:指同一物种不同种群间的个体,在自然条件下基因不能自由交流的现象。包括: a、地理隔离:由于高山、河流、沙漠等地理上的障碍,使彼此间不能相遇而不能交配。(如: 东北虎和华南虎) b、生殖隔离:种群间的个体不能自由交配或交配后不能产生可育的后代。 语句: 1、达尔文自然选择学说的内容有四方面:过度繁殖;生存斗争;遗传变异;适者生存。 2、达尔文认为长颈鹿的进化原因是:长颈鹿产生的后代超过环境承受能力(过度繁殖);它们都要吃树叶而树叶不够吃(生存斗争);它们有颈长和颈短的差异(遗传变异);颈长的能吃到树叶生存下来,颈短的因吃不到树叶而最终饿死了(适者生存)。 3、现代生物进化理论的基本内容也有四点:种群是生物进化的单位;突变和基因重组产生进化的原材料;自然选择改变基因频率;隔离导致物种形成。 4、种群基因频率改变的原因:基因突变、基因重组、自然选择。生物进化其实就是种群基因频率改变的过程。 5、基因突变和染色体变异都可称为突变。突变和基因重组使生物个体间出现可遗传的差异。 6、种群产生的变异是不定向的,经过长期的自然选择和种群的繁殖使有利变异基因不断积累,不利变异基因逐代淘汰,使种群的基因频率发生了定向改变,导致生物朝一定方向缓慢进化。因此,定向的自然选择决定了生物进化的方向。(实例——桦尺蠖在工业区体色变黑:a、从宏观上看:19世纪中期桦尺蠖的浅色性状与环境色彩相似,属于保护色,较能适应环境而大量生存;黑色性状与环境色彩差异很大,不能适应环境,易被捕食者捕食,因此,突变产生后,后代的个体数受到限制。19世纪中期到20世纪中期,由于地衣死亡,桦尺蠖栖息的树干裸露并被烟熏黑,使得黑色性状与环境色彩相似而大量生存,浅色性状与环境色彩差异很大,易被捕食者捕食而大量被淘汰。表现为适者生存,不适者被淘汰。

广外外校首届读书节图书馆推荐读物 社会科学部分 中学 1、《中国人》林语堂索书号:C955.2/14 存放地点:综合书库(二) 2、《城市季风》杨东平索书号:G122/4 存放地点:综合书库(二) 3、《苏东坡传》林语堂索书号:I25/74 存放地点:三楼文学馆 4、《论语别裁》南怀瑾索书号:B222.2/N082 存放地点:综合书库(二) 5、《美的历程》李泽厚索书号:B83-092 存放地点:综合书库(二) 6、《边城》沈从文索书号:I246.5 存放地点:综合书库(一) 7、《我的精神家园》王小波索书号:I267 存放地点:三楼文学馆 8、《守望的距离》周国平索书号:I267 存放地点:三楼文学馆 9、《中华散文百年精华》丛培香等编索书号:I266/12 存放地点:三楼文学馆 10、《空山灵雨》许地山著索书号:I266 存放地点:三楼文学馆 11、《上下五千年》林汉达、曹余章索书号:K109 存放地点:综合书库(一) 12、《与世界伟人谈心》房龙索书号:K812 存放地点:综合书库(一) 13、《苏菲的世界》乔斯坦-贾德索书号:I533.45 存放地点:综合书库(一) 14、《学生阅读经典——毕淑敏散文》索书号:I267.1 存放地点:三楼文学馆 15、《中国大历史》黄仁宇索书号:K207 存放地点:综合书库(一) 16、《杰出青少年的七个习惯:美国杰出少年训练计划》肖恩-;柯维陈允明等译 索书号:B848.4 存放地点:综合书库(二) 17、《中学人文读本》丁东等编索书号:B821-49 存放地点:综合书库(二) 18、《成功之路》拿破仑索书号:B848 存放地点:综合书库(二) 19、《林肯传》卡耐基索书号:K837.127.76 存放地点:综合书库(一) 20、《居里夫人传》艾夫-居里索书号:K837.126.11 存放地点:综合书库(一) 21、《起个好名好运一生》李然主编索书号:K810.2 存放地点:综合书库(一) 22、《瓦尔登湖》梭罗索书号:I712.64 存放地点:综合书库(一) 23、《鹰击长空》王忠瑜索书号F279/ 存放地点:综合书库(二) 24、《伟人邓小平》中共中央文献研究室邓小平研究组索书号D2-0 存放地点:综合书库(一) 25、《红岩》罗广斌杨益言索书号I247.5 存放地点:综合书库(一) 26、《青春之歌》杨沫索书号I247.51 存放地点:综合书库(一) 27、《钢铁是怎样炼成的》奥斯特洛夫斯基索书号I512.45 存放地点:综合书库(一) 28、《牛虻》优尼契李民译索书号I561.44 存放地点:综合书库(一) 29、《繁星.春水》冰心索书号I226 存放地点:综合书库(一) 30、《名人传》罗曼-罗兰索书号I565.44 存放地点:综合书库(一) 31、《假如给我三天光明》孙达译索书号K837.127 存放地点:综合书库(一) 32、《去明天的路上》洪峰索书号I217.2 存放地点:综合书库(一) 33、《女神》郭沫若索书号I226 存放地点:综合书库(一) 34、《轮椅上的梦》张海迪索书号I247.5 存放地点:综合书库(一) 35、《平凡的世界》路遥索书号I247.5 存放地点:综合书库(一) 36、《未来之路》比尔-盖茨索书号G303 存放地点:综合书库(二) 37、《世界是平的》(美)托马斯·弗里德曼著索书号D81/4 存放地点:综合书库(一)

国家数字图书馆数字资源唯一标识符系统的设计与实现 童忠勇李志尧杨东波 摘要本文针对我国图书馆数字资源建设和服务中存在的问题,提出了国家数字图书馆数字资源唯一标识符系统(简称CDOI系统)建设的必要性,分析了CDOI 系统的建设思路和设计框架,重点介绍了系统核心功能的实现方式,并对CDOI 系统在图书馆中的应用进行了展望。 关键词唯一标识符;数字图书馆;CDOI系统 Abstract:In order to solve several problems in digital resources development and services of the library which are mentioned in this paper, it is necessary to build the Digital ObjectUniqueIdentifier System of National Digital Library of China (CDOI). The paper analyzes the constructionideas and design framework of the CDOI system, and particularly introduces how to implement its core function, and then discusses its application in the future. KEYWORDS: Unique identifier.Digitallibrary. CDOI system “十二五”期间,随着数字图书馆推广工程的逐步推进,我国数字图书馆建设进入高速发展期,数字资源呈现急剧增长趋势,以数字资源为中心、围绕整个数字资源生命周期的各个业务系统逐步投入使用,业务的多样性、融合性对资源的管理和系统的建设要求越来越高。 目前,各省、市图书馆侧重于数字资源的建设和服务,但是缺乏对数字资源的规范管理,资源重复建设情况普遍存在,各应用系统的资源获取方式也是各图书馆自己定义,没有统一的接口规范,限制了图书馆应用系统间的互操作,阻碍了人们对数字资源的有效利用[1]。唯一标识符技术的出现在很大程度上解决了上述难题。数字资源的唯一标识符是数字资源的条形码[2],通过对资源的唯一标识,不仅可以将采集、加工、组织、检索、服务以及保存等各环节中的数字资源进行统一编号和规范管理,实现资源的精确定位,同时也为全国图书馆之间的数据交换和应用系统之间的互操作提供了一种新技术。 1国内外唯一标识符系统的研究现状分析 目前,国际上主流的唯一标识符系统大多是采用Handle系统[3]或者是以Handle系统作为原型进行开发的。如美国国会图书馆在“美国记忆”的数字图书馆项目中,采用Handle来标识数字对象,在全球Handle注册中心独立申请了国会图书馆的一级命名授权“loc”,二级命名授权采用收藏部门的代码[2]。日本的内容标识符论坛是以Handle系统为底层支撑技术,独立开展了唯一标识符的

欧美图书馆文化之发展历程 110403班 110654120 杨沛沛 图书馆,对我们来说是一个熟悉又陌生的词语。熟悉,是因为我们从小到大都知道我们的学校或者所在的城市乃至国家都有图书馆,我们可以去图书馆看书,查资料,借阅书籍;陌生,是因为我们对图书馆的存在,发展,文化,乃至图书馆学的了解少之又少。 图书馆其实早在公元前4世纪就已经出现。世界上最早的图书馆是亚述巴尼拔图书馆,并且保存完整。而我国作为有着五千年历史的文明古国,图书馆历史悠久,只是在我国古代不叫“图书馆”,而是称作“阁”,“院”,“斋”,“堂”等。之所以会这么早出现图书馆,我想这跟图书馆本身的职能是分不开的。图书馆是收集文献、资料、信息的地方,用来供以人们查阅、参考的机构。图书馆在人类文化发展上起着非常重要的作用。每一次文化的变革,思想的进步,图书馆都承载了记录其历程的使命。同时,从古代到现代图书馆的发展及变化也能够从侧面的反映出文化发展对图书馆的影响。 图书馆发展至今,已经成为了我们生活中不可或缺的一部分。图书馆不仅仅只是一个机构,还由此产生了一门学科,“图书馆学”。图书馆的发展与图书馆学的发展有着重要的联系。 图书馆学,是研究图书馆的发生发展、组织管理,以及图书馆工作规律的科学。其目的是总结图书馆工作和图书馆事业的实践经验,建立科学的图书馆学的理论体系,以推动图书馆事业的发展,提高图书馆在人类社会进步中的地位和作用。目前,图书馆学还是一门新兴学科,正在不断的发展中,有着很好的前景。 图书馆学的研究发展是从近代开始的,期间经历了漫长的发展时期。最著名的图书馆学家就是美国的约翰.杜威。他是19世纪后期最伟大的图书馆学家,是图书馆学的集大成者。杜威,生于1851年,21岁在Amherst学院图书馆当学生助理。在那里,杜威创立了《杜威十进分类法》(DDC)。DDC是杜威1873年创立的,1876年正式出版。DDC创立的标记符号制度以简明的方式改变了图书馆的目录排列和图书排架的制度,使图书馆的知识组织现代化,有效地提高了图书馆的工作效率。由于DDC的简明性与科学性,DDC已经成为了被世界上最多图书馆实用的分类法,已被135个国家的图书馆使用。不仅如此,他于1876年发起了费城的首届图书馆员大会,它是世界上第一个图书馆协会—美国图书馆协会(ALA)的前身。他担任过美国第一个现代大学图书馆—美国哥伦比亚大学图书馆馆长,美国第一流的州立公共图书馆—纽约图书馆的馆长。他还创办了世界上第一个正规的图书馆学教育机构—哥伦比亚大学图书馆管理学校。 在理论价值取向方面,杜威倡导的图书馆学十分注重理论的实用性。他的图书馆思想广泛传播,它孤立图书馆工作人员着眼于实际工作,多做有益于读者的事情,从而推动了图书馆学实践的发展,但同时,它禁锢了人们的思想,延缓了图书馆学的科学化进程。 紧接着,在20世纪中期,迎来了图书馆学的理性主义思潮。这一时期涌现出的思潮和图书馆学家对杜威的经验图书馆学做出了极大的挑战。 1928年芝加哥大学成立了一所具有博士学位的图书馆学院(GLS)。从GLS成立到1942年为止,GLS是美国唯一具有博士课程的图书馆学校。GLS的学风和理论追求影响了整整一代图书馆学家。GLS成立后,该校师生致力于发展具有高度理性的图书馆学知识体系,他们从历史、文化和社会的角度思考图书馆活动的哲学问题,同时也以社会科学中流行的实证方法或思辨方法研究图书馆基础理论。这一具有鲜明学术特色的学术群体,被后人称为“芝加哥学派”。提到芝加哥学派,便不能不介绍巴特勒。他是芝加哥大学GLS最早引进的具有社会科学背景的四位教师之一。他最有代表性的著作是1933年出版的《图书馆学导论》。巴特勒对图书馆学的研究方法基本上是社会科学的方法,他抓住图书馆作为社会的一种现象,他正是凭借这些与杜威完全不同的理论主张,在学院派图书馆学中赢得了巨大的声望。

《生物进化理论》教学设计 一、教材分析 本节课是高中生命科学第九章第二节的内容,教材首要介绍达尔文进化思想的来源——拉马克的进化学说,进而说明达尔文进化论形成过程——“贝格尔号”舰的环球航行,以及代表著作《物种起源》。然后通过对自然选择学说的核心内容:遗传变异、繁殖过剩、生存斗争和适者生存,以及自然选择作用例子的介绍,向学生展示达尔文进化论的主要思想和观点。学习本节内容,不仅能使学生获得有关生物进化发展的知识,更能使学生接受生动的辩证唯物主义教育。二、学情分析 学生在初中阶段已经接触过生物进化的内容,对于达尔文提出的进化理论有所了解,但是仍停留在表面,对于自然选择学说的四个要点以及它们在进化过程中所起的作用不是很清楚,并且对达尔文进化论的贡献及其局限性尚不了解。因此介绍生物进化理论的发展过程,分析达尔文进化理论的重要贡献和历史局限性,有助于学生更深刻地理解生物进化的过程,理解科学不是一个静态的体系,而是一个不断发展的动态过程。 三、教学目标 1. 知识与技能 (1)学会概述自然选择学说的基本论点。 (2)学会运用自然选择学说观点描述生物适应性的形成。 (3)学会评述达尔文自然选择学说的贡献性和局限性。 2. 过程与方法 (1)通过对拉马克和达尔文进化理论分别进行讲解,了解生物进化理论的形成过程。 (2)通过对自然选择学说四个主要论点的探讨,学会描述生物适应性的形成。 3. 情感态度与价值观 通过对达尔文生物进化学说的学习,感悟生命延续的规律,形成生物进化的观点,强化辩证唯物主义世界观。 四、教学重点和难点

1. 教学重点 达尔文自然选择学说的四个基本论点 2. 教学难点: (1)生物的适应性 (2)自然选择的作用 五、教学主线 六、教学过程设计 1. 情景导入 由地球上多种多样的物种导入,引导学生思考如此多样的物种的由来,从而引出本节课所要学习的内容。 2. 拉马克的进化学说 介绍拉马克的观点,让学生了解达尔文自然选择学说的基础之一。屏幕展示

龙源期刊网 https://www.doczj.com/doc/dd4327277.html, 从巴特勒《图书馆学导论》看我馆发展困境与改进方向 作者:李红 来源:《科技视界》2020年第06期 摘要 皮尔斯.巴特勒的《图书馆学导论》对世界图书馆的發展产生了重大的影响。该书从社会学、心理学、历史学角度揭示了图书馆的本质及功能。本文从巴特勒《图书馆学导论》的基本内容入手,结合该书研究的角度分析了三亚学院图书馆的发展困境和机遇,指出了本馆改进和发展的方向。 关键词 图书馆;图书馆学;本质;困境;改进 中图分类号: G250 ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; 文献标识码: A DOI:10.19694/https://www.doczj.com/doc/dd4327277.html,ki.issn2095-2457 . 2020 . 06 . 56 0 前言 巴特勒是美国图书馆学思想史上的一位重要作者。皮尔斯?巴特勒1886?年12月19日 出生于美国芝加哥远郊,他是家中第三子,童年体弱多病,听力不佳,小儿麻痹使他暂时跛足以及脊柱弯曲,求学之路也非一帆风顺,辗转获得神学学士、德国文学硕士学位以及神学博士学位。历经教师、牧师、图书馆员等各种职位,1952年从芝加哥大学图书馆研究生院退休。 我们今天阅读这本书,需要仔细体会当时芝加哥大学图书馆研究生院(GSL)所处的社会环境。 1 《图书馆学导论》的基本内容 本文提及的版本是2018年谢欢对《导论》的重译本,王子舟为其写了导言。在导言之后,《导论》共有五部分:第一章科学的本质,界定了“科学”一词在本书中的含义;第二三四章分别从社会学、心理学、历史问题三个角度出发,对图书馆实践领域分析的问题和现象进行了剖析;第五章阐述了对图书馆学的实践思考。

《中国基础教育文献资源总库》使用手册 目录 1.平台介绍 (1) 2.登录 (1) 3.文献分类导航 (3) 4.检索 (5) 4.1一框检索 (5) 4.2高级检索 (8) 4.3专业检索 (9) 4.4作者发文检索 (10) 4.5句子检索 (10) 5.检索结果 (10) 5.1排序 (11) 5.2设置显示记录数 (11) 5.3切换显示模式 (11) 5.4筛选 (12) 5.5导出/参考文献 (13) 5.6计量可视化分析 (14) 5.7相关学者 (15) 6.知网节 (17) 7.在线预览 (18) 8.下载 (20) 9.CAJ浏览器的使用 (21) 10.出版物导航检索 (25) 10.1期刊导航 (25) 10.2报纸导航 (29) 10.3博硕士导航 (31) 10.4会议导航 (32)

1.平台介绍 《中国基础教育文献资源总库》(简称CFED)是经国家批准正式出版,以光盘和网络为载体,连续出版的国家级专业资源库,是国家新闻出版总署“十五”国家重点电子出版项目、“十一五”国家重大出版工程项目《中国知识资源总库》和中国知识基础设施工程(CNKI工程)的重要组成部分。 CFED以数字化方式全文收录我国基础教育领域的期刊、报纸、博硕士论文、会议论文等出版资源,是当前中国基础教育领域内,最具权威、文献信息量最全最大的动态资源系统,是中国最先进的基础教育知识服务与数字化学习平台。它能有效地支持基础教育中的教育教学、科研选题、论文撰写、自主学习、研究性学习、教育管理、校本资源建设等活动,并可支持各级各类文献检索课程和信息素养课程的教学与研究。 CFED包括《中国基础教育期刊全文数据库》、《中国基础教育报纸全文数据库》、《中国基础教育博硕士学位论文全文数据库》、《中国基础教育会议论文全文数据库》等数据库。 文献量 数据库名称文献来源收录时间 中国基础教育期刊全文数据库2194种期刊1994~今1500万 中国基础教育重要报纸全文数据库518种报纸2000~今103万 中国基础教育优秀博硕士学位论文全文数据库187家院校1999~今14万 中国基础教育重要会议论文全文数据库72家单位1999~今14万 2.登录 在浏览器的地址栏中输入网址https://www.doczj.com/doc/dd4327277.html,/,即可登陆CNKI中小学数字图书馆。

第16章《生命起源和生物进化》知识点总结 苏教版 1、化学演化学说生命起源过程 原始地球火山爆发 ↓ 第一步 第二步 第三步 原始大气──→有机小分子──→有机大分子──→原始生命──→原始单细胞生物 (氨基酸等)(蛋白质、核酸等)(能生长、繁殖、遗传)。 原始大气的成分:二氧化碳、甲烷、氮气、氨、氢气和水蒸气(注意:没有氧气) 原始生命诞生的场所:原始海洋 2、生命起源的实验证据 米勒模拟原始地球条件的实验: ①火花放电的作用:模拟原始地球的闪电 ②向装置内输入的气体主要是:甲烷、氨、氢气和水蒸气 ③米勒提出的问题是:原始地球有没有可能产生生命

④米勒作出的假设是:原始地球有可能产生生命 ⑤米勒在实验中搜集到的证据是:容器中产生了原先不存在的各种氨基酸等有机小分子 ⑥米勒得出的结论是:在一定的条件下,原始大气中各种成分能够转变为有机小分子。 3、生物进化的证据 生物进化的直接证据:化石。化石是保存在地层中的古代生物的遗体、遗物和遗迹 马的进化趋势是体型由小到大,四肢越来越长,多趾着地逐渐变成只有中趾发达并惟一着地。 在德国发现的“始祖鸟”化石就是爬行类进化成鸟类的典型证据。我国辽宁省发现的孔子鸟化石为爬行类进化成鸟类提供了新证据。 越简单、越低等的生物的化石总是出现在越古老的地层里; 越复杂、越高等的生物的化石总是出现在越新近形成的地层里。 4、生物进化的主要历 生物进化的规律:从单细胞到多细胞、从低等到高等、从简单到复杂、从水生到陆生 5、达尔文的进化学说自然选择学说(“19世纪自然科学三大发现之一”)

达尔文认为,地球上的生物一般具有很强的生殖能力,但是由于食物和生活空间等条件有一定限度,因而生物会为争夺必需的食物和生活空间等进行生存斗争。生物进化是自然选择的结果。生物多样性是生物长期进化的结果 在生存斗争中,通过激烈的竞争,适者生存、不适者被淘汰的过程称为自然选择。 尝试用达尔文的自然选择学说解释长颈鹿颈长的原因:古代的长颈鹿,有颈长的和颈短的,颈的长短是可以遗传的。在环境条件发生变化,如缺乏青草的时候,颈长的可以吃到高处的树叶,就容易生存下来,并且繁殖后代。颈短的长颈鹿吃不到足够的树叶,活下来的可能性就很小,留下来的后代也更少,经过许多代以后,颈短的就被淘汰。因此,我们现在看到的长颈鹿都是颈长的。 尝试用达尔文的自然选择学说解释桦尺蛾在污染地区的黑化现象:桦尺蛾的变异会产生黑色和灰色。在污染区,黑色桦尺蛾是有利变异,在生存斗争中获胜,适者生存,并繁殖后代;灰色个体在自然选择中易被淘汰。这样在一代代的繁殖过程中,黑色个体就会越来越多,出现了在污染地区的黑化现象。 6、加拉帕戈斯雀进化的原因B 原因:自然选择

中国近代及近代以前图书馆的发展图书是图书馆构成要素的主体,图书及图书馆在我国有着极其悠久的历史。 一: xx古代图书馆的发展 我国古代图书馆大致可分为官府藏书、书院藏书、私人藏书、寺观藏书4个体系。它的主要特点是以藏为主,图书馆文献仅为少数人利用,所以人们普遍称这个时期的图书馆为藏书楼,但是古代图书馆以收藏和保存图书为主,基本上属于宫廷和神学的附属品。 根据文献和考古来看,我国的官方藏书早在夏朝就已出现。关于图书的起源,《易.系辟上》说: “河出图,洛出书”,可见在周代以前就有了藏书之举。商王朝从商汤开始就有典籍记载了推翻夏王朝的历史,并设有史官负责收藏商王的言行、前朝的文献和刻辞甲骨。其中刻辞甲骨是今人所见最丰富的原始文献,主要有干支表,记事刻辞和卜辞。甲骨卜辞更可视为一部编年体的商代百科全书,记载占卜与应验情况,是统治者寻求神权统治的依据,文献多贮藏于宗庙“龟室”中。 我国图书馆起源于周朝,周代除王室有收藏文献的库室外,各诸侯国也有本国的文献库室。另外,周朝设有专门收藏典籍的机构“盟府”,并配下史一职进行管理。《史记》记载老子曾任周朝的“收藏室之史”。班固在《汉书·艺文志》也说,老子做柱下史,博览古今典籍。 随后,从春秋到战国,我国由奴隶社会向封建社会过渡。由于“士”阶层的出现和壮大,出现了中国历史上第一个文化大发展、学术大繁荣的时期: 诸子蜂起,百家争鸣。同时社会上开始流行以竹木和绵帛为载体的文献,更加方便了社会信息的记载和传播。藏书事业也由官府著述、垄断藏书发展到公私并存,官府与知识分子俱有。这时出现了许多著名的藏书家,如孔子、老子、墨子、庄子、荀子、韩非子等。 他们收藏书籍用于著书立说,即出现了私家藏书这种新形式。

《生物的进化》知识点整理 《生物的进化》知识点整理 第七生物的进化名词: 1、过度繁殖:任何一种生物的繁殖能力都很强,在不太长的时间内能产生大量的后代表现为过度繁殖。 2、自然选择:达尔把这种适者生存不适者被淘汰的过程叫作自然选择。 3、种群:生活在同一地点的同种生物的一群个体,是生物繁殖的基本单位。个体间彼此交配,通过繁殖将自己的基因传递给后代。 4、基因库:种群全部个体所含的全部基因叫做这个种群的基因库,其中每个个体所含的基因只是基因库的一部分。 、基因频率:某种基因在整个种群中出现的比例。 6、物种:指分布在一定的自然区域,具有一定的形态结构和生理功能,而且在自然状态下能互相交配,并产生出可育后代的一群生物个体。 7、隔离:指同一物种不同种群间的个体,在自然条下基因不能自由交流的现象。包括:a、地理隔离:由于高、河流、沙漠等地理上的障碍,使彼此间不能相遇而不能交配。(如: 东北虎和华南虎)b、生殖

隔离:种群间的个体不能自由交配或交配后不能产生可育的后代。 语句:1、达尔自然选择学说的内容有四方面:过度繁殖;生存斗争;遗传变异;适者生存。 2、达尔认为长颈鹿的进化原因是:长颈鹿产生的后代超过环境承受能力(过度繁殖);它们都要吃树叶而树叶不够吃(生存斗争);它们有颈长和颈短的差异(遗传变异);颈长的能吃到树叶生存下,颈短的因吃不到树叶而最终饿死了(适者生存)。 2、现代生物进化理论的基本内容也有四点:种群是生物进化的单位;突变和基因重组产生进化的原材料;自然选择改变基因频率;隔离导致物种形成。 3、种群基因频率改变的原因:基因突变、基因重组、自然选择。生物进化其实就是种群基因频率改变的过程。 4、基因突变和染色体变异都可称为突变。突变和基因重组使生物个体间出现可遗传的差异。 、种群产生的变异是不定向的,经过长期的自然选择和种群的繁殖使有利变异基因不断积累,不利变异基因逐代淘汰,使种群的基因频率发生了定向改变,导致生物朝一定方向缓慢进化。因此,定向的自然选择决定了生物进化的方向。(实例——桦尺蠖在工业区体色变黑:a、

考试题型 一、填空题20分(20*1) 二、名词解释15分(5*3) 三、选择题30分(15*2) 四、判断题10分(10*1) 五、问答题25分(5*3+10) 课程知识要点 第1、2章基础理论部分 信息素养:信息素养(Information Literacy)也称信息素质,是指人们自觉获取、处理、传播、认识和利用信息的综合行为能力,是人们适应信息社会的要求、寻求生存和发展空间的基本保障能力。 信息素养由信息意识、信息能力、信息道德三个方面内容构成,是一个不可分割的统一整体。 信息(Information)是被反映事物属性的再现,是物质的存在方式、表现形态及运动规律的反映形式和表现特征。 情报(Intelligence)是在特定时间、特定状态下,对特定的人提供的有用知识和信息。 文献是记录有知识的一切载体。 信息资源是经过人类筛选、组织、加工并可以存取、能够满足人类

需求的各种信息的集合。 按照信息载体形态,信息源主要有:口语(口头)信息源、实物信息源、文献信息源 文献的三个基本要素:信息内容、载体材料、记录方式 按照出版形式,十大文献信息源(P19-20) 信息检索是指将信息按一定方式组织和存储起来,并根据用户的需要找出相关信息的过程。 检索语言是根据信息检索的需要创造出来的一种人工语言,是在信息检索领域中用来描述信息特征和表达信息检索提问的一种专用语言。 检索语言的主要类型分类检索语言和主题检索语言 我国分类检索语言使用最广泛的两种:《中图法》以字母+数字为标识符号《科图法》以数字为标识符号 信息检索手段:手工检索(简称手检)、计算机检索(简称机检) 检索工具:是指人们用来报道、存储和查找信息线索的工具。它是检索标识的集合体,它的基本职能一方面是揭示信息及其线索,另一方面提供一定的检索手段,使人们可以按照它的规则,从中检索出所需信息的线索。

图书馆:历史、现在和未来

————————————————————————————————作者:————————————————————————————————日期:

图书馆:历史、现在和未来-建筑论文 图书馆:历史、现在和未来 徐长柱 (济南大学图书馆,山东济南250022) 【摘要】图书馆的信息环境在最近几十年发生了急剧的变化,回眸历史,由藏书楼到现代层出不穷的未来图书馆新概念,可以以资参照。并对解决作为当下困惑业界的图书馆发展趋势问题,以及更好的解决图书馆转型问题提供一些粗浅的思路。 关键词图书馆;藏书楼;信息环境 在最近的几十年,图书馆界一直在追问:在时代急剧发生的根本性改变的基础信息环境下,图书馆的职能怎样才能最大程度地实现?全球性的信息战略的影响,一方面使图书馆发展的社会和技术等诸要素发生了剧烈的变化;另一方面,图书馆员具备的传统的业务技能已经追不上现代化发展的要求。图书馆员的职业使命怎样才能实现?图书馆的形态和业务发生了显而易见的变化。整个社会,无论是科研环境、教育领域还是公共领域中的时代变革既是挑战也是机遇,重新定位图书馆的价值,实现转型和再生长成为蜕变时代必须厘清的主题。 1 历史回眸:藏书楼与近现代图书馆之“信息深井” 图书馆作为一个专门收集、整理、加工、保存、传播文献并提供利用的机构,它的产生和出现经历了漫长的“藏书楼”,时代,迄今已有数千年的历史。 我国最早从周朝就有了专门的藏书机构。秦王朝,设置“柱下史”负责管理图书。汉朝时期,刘向、刘歆父子整理、编成我国最早的藏书目录《七略》,开创了我国图书馆学术的肇始元年。我国的私人藏书始自隋、唐。及至宋代,皇室藏

数字图书馆资源建设和服务中的 知识产权保护政策指南 (2010年7月15日) 第一条在数字图书馆资源建设和服务过程中均涉及知识产权保护问题。为指导全国数字图书馆建设和服务中的知识产权保护和知识传播服务,根据《中华人民共和国著作权法》、《中华人民共和国著作权法实施条例》、《信息网络传播权保护条例》和《著作权集体管理条例》等法律法规,特制订本指南。 第二条本指南中的知识产权是指在数字图书馆资源建设和服务过程中涉及到的作品的著作权及其相关权益、专利权、商标权等。 第三条在数字图书馆的资源建设和服务过程中,应注重知识产权的保护,坚持公益性原则、利益平衡原则、实用性原则,确保数字图书馆建设的健康、科学、可持续发展。 公益性原则是指数字图书馆资源建设和服务中的知识产权保护应以促进知识的创建与传播,保障公众获取信息的权利,满足公众的信息需求为出发点,不以营利为目的。 利益平衡原则是指数字图书馆资源建设和服务中的知识产权保护既要保护知识产权权利人的利益,也要保护图书馆及社会公众的利益。 实用性原则是指数字图书馆资源建设和服务中的知识产权保护方案、手段要具有可操作性,要符合数字图书馆建设实践的需要,符合知识产权保护的需要,要有利于数字图书馆的发展。 第四条在数字图书馆资源建设和服务过程中,应当按照《中华人民共和国著作权法》的规定,区分不受著作权法保护的作品及受著作权法保护的作品。对于受著作权法保护的作品,要进一步确认哪些作品已过权利保护期,哪些作品仍处于权利保护期,在此基础上开展下一步工作。 第五条不受著作权法保护的作品包括: 1、法律、法规,国家机关的决议、决定、命令和其他具有立法、行政、司法性质的文件,及其官方正式译文; 2、时事新闻;