Awarding a Prize_ An Ethnography of a Juried Ceramic Art Exhibition in Japan

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:1.67 MB

- 文档页数:32

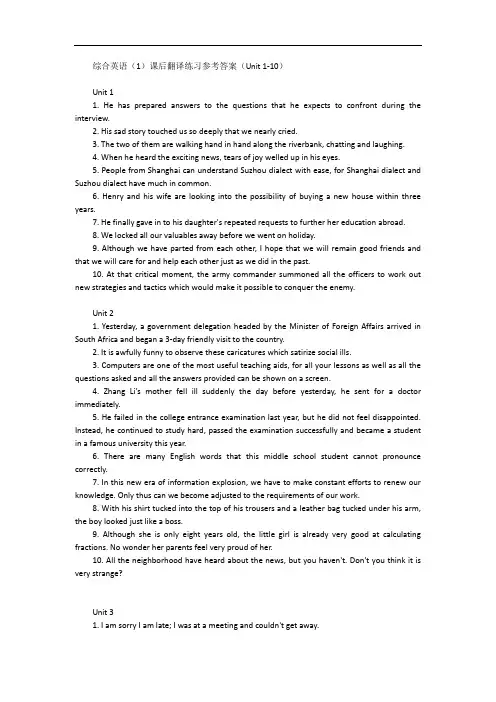

综合英语(1)课后翻译练习参考答案(Unit 1-10)Unit 11. He has prepared answers to the questions that he expects to confront during the interview.2. His sad story touched us so deeply that we nearly cried.3. The two of them are walking hand in hand along the riverbank, chatting and laughing.4. When he heard the exciting news, tears of joy welled up in his eyes.5. People from Shanghai can understand Suzhou dialect with ease, for Shanghai dialect and Suzhou dialect have much in common.6. Henry and his wife are looking into the possibility of buying a new house within three years.7. He finally gave in to his daughter's repeated requests to further her education abroad.8. We locked all our valuables away before we went on holiday.9. Although we have parted from each other, I hope that we will remain good friends and that we will care for and help each other just as we did in the past.10. At that critical moment, the army commander summoned all the officers to work out new strategies and tactics which would make it possible to conquer the enemy.Unit 21. Yesterday, a government delegation headed by the Minister of Foreign Affairs arrived in South Africa and began a 3-day friendly visit to the country.2. It is awfully funny to observe these caricatures which satirize social ills.3. Computers are one of the most useful teaching aids, for all your lessons as well as all the questions asked and all the answers provided can be shown on a screen.4. Zhang Li’s mother fell ill suddenly the day before yesterday, he sent for a doctor immediately.5. He failed in the college entrance examination last year, but he did not feel disappointed. Instead, he continued to study hard, passed the examination successfully and became a student in a famous university this year.6. There are many English words that this middle school student cannot pronounce correctly.7. In this new era of information explosion, we have to make constant efforts to renew our knowledge. Only thus can we become adjusted to the requirements of our work.8. With his shirt tucked into the top of his trousers and a leather bag tucked under his arm, the boy looked just like a boss.9. Although she is only eight years old, the little girl is already very good at calculating fractions. No wonder her parents feel very proud of her.10. All the neighborhood have heard about the news, but you haven't. Don't you think it is very strange?Unit 31. I am sorry I am late; I was at a meeting and couldn't get away.2. At the concert, whenever a singer finished singing a beautiful song, the audience would burst into loud cheers to show their appreciation.3. As a stylish dresser, she is always wearing stylish clothes, but she seldom cares about what she eats or drinks.4. The nurse tells me that the doctors have done wonders for your heart disease.5. When awarding the prize, the chairman complimented the winner on his great contribution to mankind.6. This problem has bothered the experts for many years.7. The crowd of demonstrators melted away when the police arrived.8. Since punctuality is a good habit, we should pay much attention to it and make great efforts to cultivate this good habit.9. The old man cherishes that girl, as if she were his own daughter.10. It is just a routine physical checkup, nothing to get worded about.Unit 41. It is a systematic attempt to strengthen our competitive ability.2. The police in this district know where the thieves hang out.3. The agreements signed will break down all barriers to free trade.4. It was a very difficult situation, but he handled it quite successfully.5. He is my best friend. I just can't turn my back on him now that he needs my help.6. So long as you work hard, you are bound to succeed and realize your ambition sooner or later.7. Although he hates the job, yet he is determined to stick it out because he needs the money to support his family.8. That cancer patient kept an optimistic attitude towards his disease, persisted in combating it, and conquered it in the end.9. This university has a staff of more than 2000, including about 150 professors and over 500 associate professors.10. The concert was held to mark the 75th anniversary of the composer's death.Unit 51. That psychiatrist, who had talked about his patients, was charged with violating professional ethics.2. Hanging on the walls of the classroom are some famous sayings, which inspire and urge people to exert themselves.3. All kinds of commodities are available. Nothing is in short supply.4. We all trust the president of the board of directors, who is a man of absolute integrity.5. Before we vote for him, we want to know what he stands for.6. The defendant couldn't account for the fact that the money was found in his house.7. When I saw that he was right, I had to back down.8. She has been appointed sales director, for she is both clever and diligent.9. One of the biggest challenges faced by the present government is that of creating more jobs.10. The enemy succumbed soon after our soldiers stormed its stronghold.Unit 61. The dilemma she is facing is whether to tell her husband the truth about his fatal disease.2. Don’t you think it a sort of stigma that you, already in your thirties, still have to depend on your old parents?3. Almost all the governments in the world are very much concerned about the financial issue.4. With regard to the seminar on English teaching (the English seminar), I suggest we hold it at the weekend (this weekend).5. Whether to go abroad for further education or not is entirely up to you.6. Just a single spark can lead to an explosion in a room filled with gas.7. No matter what efforts the government has made, the price of housing has barely declined.8. In order to pass TOEFL, he has devoted every minute of his spare time to English studies.9. With his acting potential, the young man is likely to be a superstar in the field of entertainment.10. It is believed that sibling jealousy exists more in a rich family than in a poor one.Unit 71. I scrambled up the cliff for a better view of the sea.2. He lunged at the burglar and wrestled with him for the weapon.3. I figure that our national economy will continue to develop rapidly.4. The chairman made effort to reassure the shareholders that the company's bad results would not be repeated.5. Stop acting like a baby! Pull yourself together!6. Being very much a private man, he does not confide in anyone.7. We all hate the terrorists' indiscriminate violence against ordinary people.8. Many people in this country are alarmed by the dramatic increase in violent crime.9. We anticipated that the enemy would try to cross the river. That was why we destroyed the bridge.10. I am indebted to all the people who worked so hard to make the party a great success.Unit 81. At Christmas people enjoy themselves very much; they visit one another and present each other with Christmas cards and presents.2. The walls of her bedroom and living room are all decorated with pictures of pop stars and film stars.3. Sophia teased Tom about his new hat mildly, but Tom teased her about her curly hair unmercifully.4. He had attained remarkable achievements which surpassed the goal he had set for himself.5. He kept crying bitterly and I tried to persuade him not to give way to grief.6. I took it for granted that you would want to see the play, so I bought you a ticket.7. They have relegated these problems somewhere down on the priority list.8. I am going to address the letter to Donna in care of her lawyer.9. I could not account for the lump in my throat as I was telling her the news.10. Sailors signal with flags by day and with lights at night.Unit 91. Towering above all the others, this mountain peak commands a fine view.2. I have asked my friends to recommend a doctor who is good at treating children.3. The children were swinging on a rope hanging from a tree.4. Direct contact with the patients suffering from SARS must be avoided at all costs.5. Being cruel, treacherous, and unscrupulous, that terrorist committed murder, arson, and every crime imaginable.6. That old woman is always interfering in other people's affairs.7. After having several influential papers published, he became quite distinguished in the academic world.8. The huge outdoor amphitheater is an attractive place, where symphonies by great musicians are played every summer.9. He packed a briefcase with what might be required, while I packed a suitcase with all the things that might be needed.10. We Chinese usually associate the Spring Festival with family reunion.Unit 101. Some students longed to study what they want to, not what they are asked to.2. Many volunteers rendered a valuable service to the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games.3. The world economy is in a desperate situation, so all governments must take desperate measures to cope with it.4. Scissors, knives, matches and medicine must be kept beyond the reach of children.5. I always keep a sum of at least 1, 000 yuan on hand, in case of an emergency.6. Honest people despise lies and liars.7. It was a long time before I began to feel at home in English.8. Because of the financial recession, some of the entrepreneurs who are running small and middle-sized businesses are, so to speak, up to their necks in debt.OR: Because of the financial recession, some of those running small and medium-sized businesses are, so to speak, up to their necks in debt.9. He is a man who always mouths fine words about people to their faces and speaks ill of them behind their backs.10. I was greatly scared by the zest demonstrated by those radicals.。

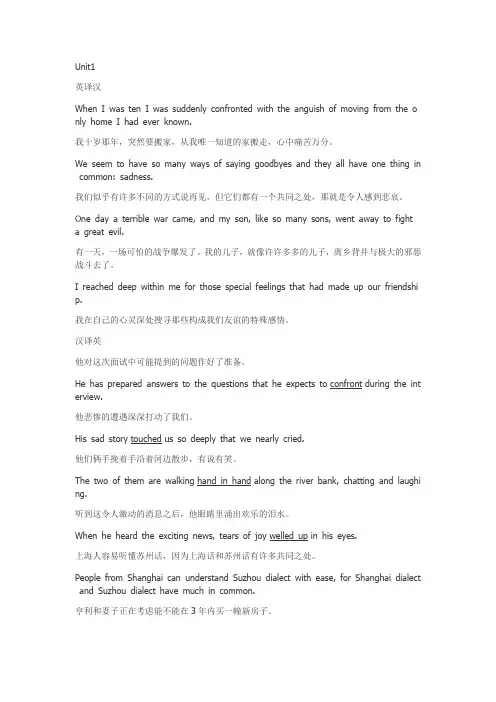

Unit1英译汉When I was ten I was suddenly confronted with the anguish of moving from the o nly home I had ever known.我十岁那年,突然要搬家,从我唯一知道的家搬走,心中痛苦万分。

We seem to have so many ways of saying goodbyes and they all have one thing in common: sadness.我们似乎有许多不同的方式说再见,但它们都有一个共同之处,那就是令人感到悲哀。

One day a terrible war came, and my son, like so many sons, went away to fight a great evil.有一天,一场可怕的战争爆发了。

我的儿子,就像许许多多的儿子,离乡背井与极大的邪恶战斗去了。

I reached deep within me for those special feelings that had made up our friendshi p.我在自己的心灵深处搜寻那些构成我们友谊的特殊感情。

汉译英他对这次面试中可能提到的问题作好了准备。

He has prepared answers to the questions that he expects to confront during the int erview.他悲惨的遭遇深深打动了我们。

His sad story touched us so deeply that we nearly cried.他们俩手挽着手沿着河边散步,有说有笑。

The two of them are walking hand in hand along the river bank, chatting and laughi ng.听到这令人激动的消息之后,他眼睛里涌出欢乐的泪水。

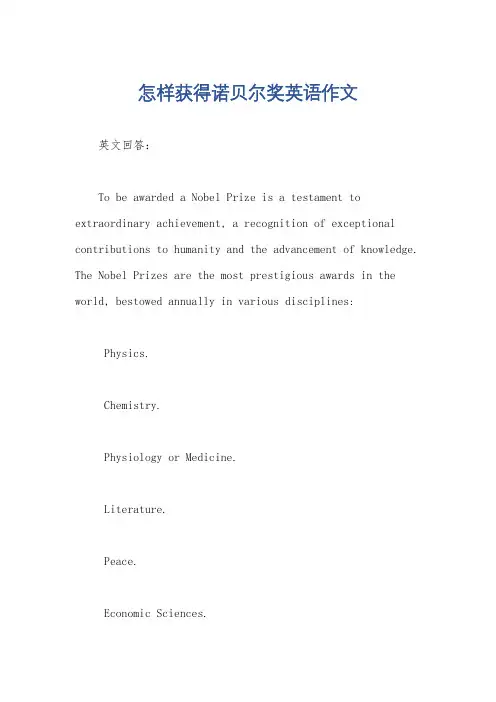

怎样获得诺贝尔奖英语作文英文回答:To be awarded a Nobel Prize is a testament to extraordinary achievement, a recognition of exceptional contributions to humanity and the advancement of knowledge. The Nobel Prizes are the most prestigious awards in the world, bestowed annually in various disciplines:Physics.Chemistry.Physiology or Medicine.Literature.Peace.Economic Sciences.The path to winning a Nobel Prize is arduous and highly competitive. It requires years of dedication, perseverance, groundbreaking research, and the ability to transcend the boundaries of existing knowledge.There is no formula or guaranteed method to secure a Nobel Prize, but certain factors can increase thelikelihood of recognition:Excellence in Research: Nobel laureates are typically at the forefront of their fields, making significant discoveries and advancements.Innovation and Originality: Nobel Prizes often honor work that breaks new ground and challenges established paradigms.Impact on Society: Nobel Prizes recognize work that has a profound impact on humanity, improving lives or expanding our understanding of the world.Dissemination of Knowledge: Nobel laureates are expected to share their knowledge and discoveries with the global community through publications, lectures, and collaborations.International Collaboration: Nobel Prizes often recognize work that transcends national boundaries and fosters international cooperation.The Nobel Prize is not merely an accolade but a testament to a life dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge, innovation, and the betterment of humanity. It is a recognition of exceptional contributions that have shaped our understanding of the world and continue to inspire future generations.中文回答:要获得诺贝尔奖,这是一种非凡成就的证明,是对为人类和知识进步做出杰出贡献的认可。

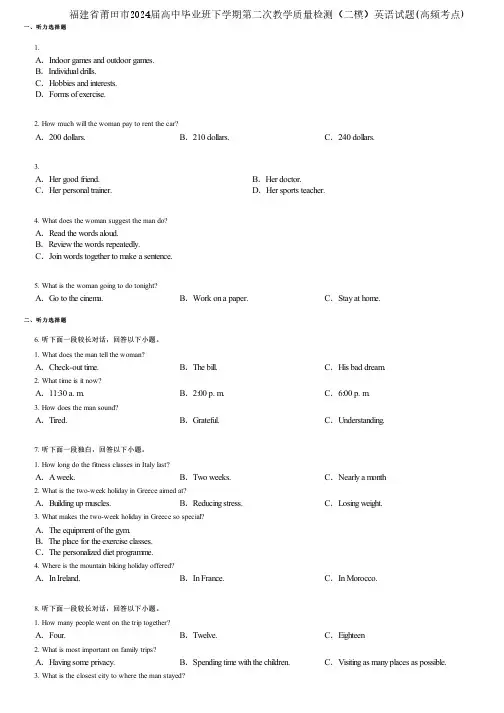

福建省莆田市2024届高中毕业班下学期第二次教学质量检测(二模)英语试题(高频考点)一、听力选择题1.A.Indoor games and outdoor games.B.Individual drills.C.Hobbies and interests.D.Forms of exercise.2. How much will the woman pay to rent the car?A.200 dollars.B.210 dollars.C.240 dollars.3.A.Her good friend.B.Her doctor.C.Her personal trainer.D.Her sports teacher.4. What does the woman suggest the man do?A.Read the words aloud.B.Review the words repeatedly.C.Join words together to make a sentence.5. What is the woman going to do tonight?A.Go to the cinema.B.Work on a paper.C.Stay at home.二、听力选择题6. 听下面一段较长对话,回答以下小题。

1. What does the man tell the woman?A.Check-out time.B.The bill.C.His bad dream.2. What time is it now?A.11:30 a. m.B.2:00 p. m.C.6:00 p. m.3. How does the man sound?A.Tired.B.Grateful.C.Understanding.7. 听下面一段独白,回答以下小题。

1. How long do the fitness classes in Italy last?A.A week.B.Two weeks.C.Nearly a month2. What is the two-week holiday in Greece aimed at?A.Building up muscles.B.Reducing stress.C.Losing weight.3. What makes the two-week holiday in Greece so special?A.The equipment of the gym.B.The place for the exercise classes.C.The personalized diet programme.4. Where is the mountain biking holiday offered?A.In Ireland.B.In France.C.In Morocco.8. 听下面一段较长对话,回答以下小题。

万圣节的安排英语作文As the crisp autumn air sets in, the excitement for Halloween begins to build. This year, I have a series of plans that promise to make the most out of the spooky season. Here's a glimpse into my Halloween arrangements:Themed DecorationsThe first order of business is to transform my home into a haunted haven. I plan to string up cobwebs, hang ghostly figures from the trees, and carve pumpkins into Jack-o'-lanterns with eerie faces. The front porch will be adorned with flickering LED candles and a "Beware of Ghosts" sign to set the mood for trick-or-treaters.Costume PartyOn the eve of Halloween, I'm hosting a costume party for friends and family. Everyone is encouraged to come dressed as their favorite character or monster. I'll be judging the best costume and awarding a prize to the winner. The party will feature Halloween-themed games like "Pin the Tail on the Witch" and "Bobbing for Apples."Trick-or-TreatingAfter the party, the younger guests and I will embark on a trick-or-treating adventure around the neighborhood. We'll make sure to check the treats for any signs of tampering and enjoy the spectacle of various houses decked out in Halloween finery.Movie NightOnce we're back from trick-or-treating, it's time to settlein for a Halloween movie marathon. I've curated a list of classic horror films and family-friendly spooky movies thatwill keep us entertained well into the night.Community EventOur community center is organizing a Halloween fair with a pumpkin carving contest, a haunted house, and a magic show. I plan to participate in the pumpkin carving contest and maybe even volunteer to help with the haunted house.Safety MeasuresGiven the current global health situation, I'll be ensuring that all activities adhere to safety guidelines. Thisincludes providing hand sanitizers, encouraging mask-wearing when necessary, and maintaining social distancing during the party and trick-or-treating.Halloween is not just about scares; it's a time for community, creativity, and loads of fun. With these plans in place, I'm looking forward to a memorable and enjoyable Halloween celebration.。

获得诺贝尔奖的人物介绍英语作文1Tu Youyou is a remarkable figure who has made an indelible contribution to the field of global health and medicine. Born in Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, China, she dedicated her life to scientific research.Tu Youyou's most significant achievement lies in her discovery of artemisinin, a breakthrough in the treatment of malaria. Her journey was far from easy. It involved countless experiments, extensive research, and unwavering determination. Facing numerous challenges and setbacks, she persisted without giving up.The discovery of artemisinin has had an extraordinary impact on global health. It has saved countless lives, especially in regions where malaria is endemic. Her work has not only alleviated the suffering of patients but also provided a powerful tool for combating this deadly disease.Tu Youyou's contribution extends beyond the realm of medicine. Her perseverance and dedication have inspired countless scientists and researchers. Her story serves as a reminder that with hard work and a spirit of exploration, great achievements can be made to benefit humanity.In conclusion, Tu Youyou's name will forever be engraved in the annals of history as a symbol of scientific excellence and humanitarianism. Her work will continue to inspire future generations to strive for thebetterment of the world.2Marie Curie, a name that resonates through the corridors of scientific history, is a remarkable figure whose dedication and perseverance have left an indelible mark on the world. Born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1867, Marie Curie faced numerous challenges and prejudices in a time when women's access to education and scientific research was severely limited.Despite the odds stacked against her, Marie Curie was undeterred. She conducted her groundbreaking research in often-harsh conditions, with limited resources and equipment. Her focus was on the study of radioactive substances, a field that was largely unexplored at the time.Her determination led to the discovery of polonium and radium, elements that revolutionized the understanding of atomic structure and radiation. This was no small feat, considering the painstaking process of extracting and purifying these substances.Marie Curie's work was not only scientifically significant but also an inspiration to countless individuals. Her persistence in the face of adversity, her unwavering commitment to the pursuit of knowledge, and her willingness to push the boundaries of what was known are qualities that define true scientific excellence.Even in the face of personal tragedy and ill health due to her prolonged exposure to radiation, Marie Curie remained steadfast in her passion forscience. Her legacy lives on, serving as a beacon of hope and determination for future generations of scientists.3Mo Yan is a remarkable figure who has won the Nobel Prize in Literature. His works have left an indelible mark on the literary world.Mo Yan's literary creations are characterized by a rich and vivid portrayal of rural life in China. His novels often delve deep into the complexities of human nature and social issues. For instance, in his renowned work "Red Sorghum," he vividly depicts the struggles and hopes of the common people, presenting a panorama of rural society.His unique narrative style and powerful language have not only captivated readers within China but have also attracted a global audience. Through his works, he has opened a window for the world to understand the profound changes and cultural heritage of China.Mo Yan's achievements have played a significant role in promoting Chinese literature to the international stage. His success has encouraged more Chinese writers to pursue excellence and has enhanced the global influence of Chinese literature. His works have sparked cross-cultural dialogues and have contributed to the diversity and enrichment of the world's literary landscape.In conclusion, Mo Yan's contributions to literature are highly valuable, and his works will continue to inspire and enlighten readers for generationsto come.4Albert Einstein, one of the most renowned physicists of the 20th century, was a revolutionary thinker whose contributions transformed our understanding of the universe. His theory of relativity, composed of the special theory of relativity and the general theory of relativity, stands as a remarkable achievement that has forever changed the landscape of physics.The special theory of relativity, proposed by Einstein in 1905, challenged the conventional notions of time and space. It introduced the concept that the laws of physics are the same for all non-accelerating observers and that the speed of light is a constant regardless of the motion of the source or the observer. This radical idea not only revolutionized our understanding of the nature of light but also had profound implications for the concepts of simultaneity and time dilation.The general theory of relativity, developed in 1915, took the understanding of gravity to a new level. It proposed that gravity is not a force but rather a curvature of spacetime caused by the presence of mass and energy. This theory predicted phenomena such as the bending of light by massive objects and the precession of the perihelion of Mercury, which were later confirmed by experiments and observations.Einstein's work not only advanced the field of physics but also inspired countless scientists to pursue bold and innovative ideas. Histhinking was characterized by a willingness to question established beliefs and to envision new possibilities. His perseverance and intellectual courage in the face of skepticism and conventional wisdom serve as an inspiration to all those who strive for intellectual breakthroughs and the pursuit of truth.5Martin Luther King Jr., a name that resonates through the corridors of history, was an extraordinary figure whose impact still reverberates to this day. Born in an era marked by deep-seated racial discrimination and injustice, King emerged as a beacon of hope and change.The social backdrop against which King operated was rife with prejudice and inequality. Segregation was the norm, and African Americans faced systemic oppression in various aspects of life, from education and employment to basic civil rights. However, King refused to accept this status quo. His unwavering commitment to nonviolent resistance and his powerful oratory skills became the driving forces behind the Civil Rights Movement.His speeches, filled with passion and moral clarity, struck a chord in the hearts of millions, inspiring them to join the fight for equality. King's vision of a society where people were judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character was not only revolutionary but also a clarion call for justice.It was this unwavering dedication and the profound impact of hisefforts that led to his being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The Nobel Committee recognized the significance of his work in fostering social change and promoting peace through nonviolent means.In conclusion, Martin Luther King Jr.'s achievements were not merely individual triumphs but were deeply intertwined with the social and cultural context of his time. His story serves as a reminder of the power of perseverance, moral courage, and the collective pursuit of a more just and equitable world.。

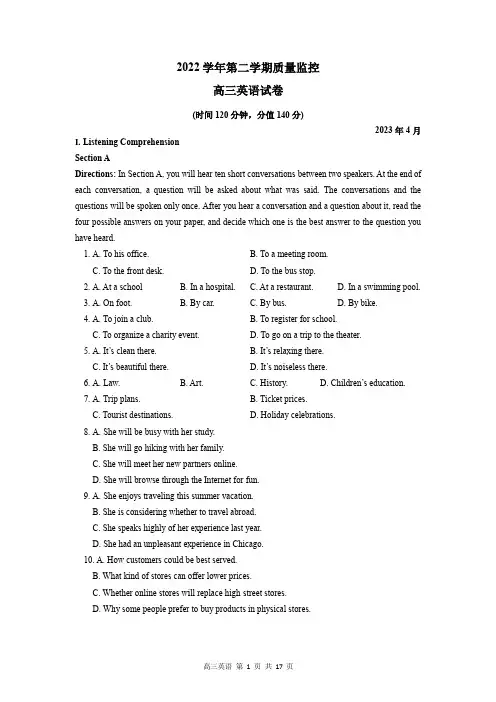

2022学年第二学期质量监控高三英语试卷(时间120分钟,分值140分)2023年4月I.Listening ComprehensionSection ADirections: In Section A, you will hear ten short conversations between two speakers. At the end of each conversation, a question will be asked about what was said. The conversations and the questions will be spoken only once. After you hear a conversation and a question about it, read the four possible answers on your paper, and decide which one is the best answer to the question you have heard.1.A. To his office. B. To a meeting room.C. To the front desk.D. To the bus stop.2.A. At a school B. In a hospital. C. At a restaurant. D. In a swimming pool.3.A. On foot. B. By car. C. By bus. D. By bike.4.A. To join a club. B. To register for school.C. To organize a charity event.D. To go on a trip to the theater.5.A. It’s clean there. B. It’s relaxing there.C. It’s beautiful there.D. It’s noiseless there.6.A. Law. B. Art. C. History. D. Children’s education.7.A. Trip plans. B. Ticket prices.C. Tourist destinations.D. Holiday celebrations.8.A. She will be busy with her study.B. She will go hiking with her family.C. She will meet her new partners online.D. She will browse through the Internet for fun.9.A. She enjoys traveling this summer vacation.B. She is considering whether to travel abroad.C. She speaks highly of her experience last year.D. She had an unpleasant experience in Chicago.10. A. How customers could be best served.B. What kind of stores can offer lower prices.C. Whether online stores will replace high-street stores.D. Why some people prefer to buy products in physical stores.Section BDirections:In Section B, you will hear two short passages and one longer conversation, and you will be asked several questions on each of the passages and the conversation. The passages and the conversation will be read twice, but the questions will be spoken only once. When you hear a question, read the four possible answers on your paper and decide which one would be the best answer to the question you have heard.Questions 11 through 13 are based on the following passage.11. A. A host. B. A patient. C. A doctor. D. A volunteer.12. A. Lawyer. B. Driver. C. Researcher. D. Government officer.13. A. By reading books regularly.B. By changing your demanding job.C. By developing some challenging hobbies.D. By exercising regularly and eating healthily.Questions 14 through 16 are based on the following passage.14. A. About 150. B. About 12. C. About 15. D. About 5.15. A. They have limited access to friends’ updates.B.They get pressure from their friends in real life.C.They make virtual friends with their employers.D.What they post online may offend their friends.16. A. Online friendship is of significance for teenagers.B.Teenagers interact with their friends mostly on line.C.Teenagers’ online friendship is superior to that in real life.D.A majority of teenagers prefer to make new friends online.Questions 17 through 20 are based on the following conversation.17. A. Repainting the walls. B. Furnishing the kitchen.C.Renting an apartment.D. Discussing the pipe system.18. A. It is in a rural area. B. The fridge works well.C. It is next to the office.D. Laundry is included in the rent.19. A. For a week. B. For a month.C.For about three years.D. For at least a year.20. A. $200. B. $180. C. $720. D. $800.II. Grammar and VocabularySection ADirections: Read the following passage. Fill in the blanks to make the passage coherent. For the blanks with a given word, fill in each blank with the proper form of the given word. For the other blanks, fill in each blank with one proper word. Make sure that your answers are grammatically correct.OpenAI Announces ChatGPT Successor GPT-4OpenAI has released GPT-4, the latest version of its hugely popular artificial intelligence chatbot ChatGPT.The new model can respond to images by providing recipe suggestions from photos of ingredients as well as writing captions and descriptions. It can also process up to 25,000 words, about eight times as many as ChatGPT. Millions of people have used ChatGPT since it (21) __________ (launch) in November 2022. Popular requests for it include writing songs, poems, marketing copy, computer code, and helping with homework, (22) __________ teachers say students shouldn’t use it. ChatGPT answers questions (23) __________ (employ) natural human-like language, and it can also imitate other writing styles such as songwriters and authors, using the Internet as its knowledge database.There are concerns that it could one day take over many jobs currently (24) __________ (do) by humans. OpenAI said it (25) __________ (spend) six months on safety features for GPT-4, and on human feedback. However, it warned that it (26) __________ still be subject to sharing disinformation.GPT-4 will initially be available to ChatGPT Plus subscribers, (27) __________ pay $20 per month for easy access to the service. It’s already powering Microsoft’s Bing search engine platform. The tech giant has invested $10b (28) __________ OpenAI.GPT-4 has “(29) __________ (advanced) reasoning skills” than ChatGPT, OpenAI said. The model can, for example, find available meeting times for three schedules.OpenAI also announced new partnerships with language learning app Duolingo and Be My Eyes, an application for the visually impaired, (30) __________ (create) AI Chatbots which can assist their users using natural language.However, like its predecessors (被替代的事物), OpenAI has warned that GPT-4 is still not fully reliable and it may invent facts or make reasoning errors.Section BDirections: Complete the following passage by using the words in the box. Each word can only be used once. Note that there is one word more than you need.A. breakthroughsB. coreC. driverD. empowerE. fullyF. increasinglyG. mountingH. potentialI. promotingJ. seeksK. servesCompanies Help Integrate (整合) Digital Real Economies Chinese platform companies are doubling down on the most advanced digital technologies to seek new drivers in revenue(财政收入)growth, as the country puts greater emphasis on (31) _________ the in-depth integration of the digital and real economies, experts and company executives said.Despite the depressing global outlook and (32) __________ uncertainties, China’s platform economy is playing a(n) (33) _________ vital role in boosting technological innovation and high-quality development.During an earnings conference with investors on Thursday, Zhang Yong, chairman and CEO of Alibaba Group, said that cloud computing is one of the company’s (34) ________ strategies for the future, and Alibaba Cloud is also the foundation through which the company (35) _________ the real economy and drives the integration of the digital and real economies.Noting that this is a critical period for technological (36) __________ and development in cloud computing and AI, Zhang said he believed in the vast (37) ____________ of industrial digitalization and the role of cloud computing as the focus of the digital economy.Revenue in the cloud business, Alibaba’s main growth (38) __________ besides e-commerce, reached 20.18 billion yuan during the October-December period, an increase of 3% year-on-year, mainly driven by public cloud growth.The company is making efforts to make use of digital technologies to help small and medium-sized enterprises and speed up industrial transformation (工业转型) in an effort to (39) __________ the real economy.The tone-setting Central Economic Work Conference in mid-December said that platform companies will be supported to “(40) _________ display their capabilities” in encouraging economic growth, job creation and international competition. The conference also emphasized the need to energetically develop the digital economy.III. Reading ComprehensionSection ADirections: For each blank in the following passage there are four words or phrases marked A, B, C and D. Fill in each blank with the word or phrase that best fits the context.It is Nobel Prize week, the one week every year when people from all corners of the globe celebrate science, read about ribosomes (核糖体), and give their best shot at trying to understand particle physics. It is also the one week when science is guaranteed some prime headline space on mainstream news outlets. And yet the science Nobels (in medicine, physics, and chemistry) present a(n) (41) ______ view of science.The problem starts with the (42) ______ of prize-winners selected every year. The rules governing the Nobel Prize (43) ______ it to just three winners in each category. This means that for every discovery that is awarded a Nobel, the majority of contributing scientists end up being (44) ______.As a matter of fact, science has never been a(n) (45) ______ effort. Isaac Newton stood on the “shoulders of giants”; Neil Armstrong’s “one small step” was a dream realized by hundreds of thousands of engineers and scientists. Science is, and always has been, and repetitive process where individuals draw on discoveries made by others to (46) ______ advance the boundaries of human knowledge. Yes, Albert Einstein famously won the Nobel Prize all by himself for a paper he alone authored, but he could not have made his discoveries without (47) ______ work by Max Planck, James Maxwell, and several others.To make matters worse, typical of the Nobel Prizes, none of the (48) ______ was a first author on any of the publications cited by the prize announcements. The first author of a scientific paper is typically the person who did the hands-on laboratory work, usually a graduate student or young post-doctoral researcher. It is precisely these (49) ______ researchers who are in greater need of the Nobel Prize money than their generally tenured (终身的) supervisors.More basically, awarding the prizes to only three scientists spreads a vision of science as an individual enterprise. By ensuring that graduate students are not given (50) ______ recognition, the prizes reinforce (加强) the mistaken image of a scientist as an old white man in a lab coat. This can only (51) ______ gender and racial inequalities in science, especially further along in an academic career.Any one of these reasons is sufficient to (52) ______ the Nobel Prizes. Here is one idea: Award the Nobel Prizes not to (53) ______ but for discoveries; donate the prize money to aninternational science fund to promote further exploration in each year’s prize-winning field of research.A science-oriented Nobel, rather than a scientist-oriented one, would educate the public in the most important scientific developments and, (54) ______, stimulate new scientific progress by using the prize money to fund the next generation of researchers. Science works best when the (55) ______ of one generation of scientists are paid forward to drive the next to even greater heights. That is to say, scientists of different generations work with joint efforts to support future scientific advancements for the betterment of society as a whole.41.A. strange B. outdated C. all-round D. advanced42.A. quality B. diversity C. discipline D. figure43.A. restrict B. extend C. relate D. apply44.A. employed B. ignored C. respected D. nominated45.A. terrific B. constant C. intellectual D. individual46.A. naturally B. rapidly C. gradually D. personally47.A. previous B. subsequent C. physical D. commercial48.A. employees B. addressees C. awardees D. refugees49.A. chief-position B. early-careerC. senior-managementD. academic-world50. A. due B. immediate C. literary D. governmental51. A. turn down B. level off C. take away D. step up52. A. claim B. reform C. present D. announce53. A. organizers B. researchers C. sponsors D. supervisors54. A. in fact B. in comparison C. in theory D. in turn55. A. legends B. spirits C. achievements D. mysteriesSection BDirections: Read the following three passages. Each passage is followed by several questions or unfinished statements. For each of them there are four choices marked A, B, C and D. Choose the one that fits best according to the information given in the passage you have just read.(A)On the track for the 400-meter dash at the 1958 British Empire and Commonwealth Games, Mikha Singh shot from the start as fast as possible, but then, in a second, sensed Malcolm Spence of South Africa over his shoulder. At the line, with six inches between them, Singh won the gold.The audience broke into applause. To them, however, he was just a village boy who ran with his arms gracefully waving. They did not know that, for him, running was not a sport. It was everything, his religion, his beloved, and his life.As a child, Singh ran to get an education outside his home village. The school was ten kilometers away. But at the age of 18, Singh ran to save his very life. In 1947, the village was being split between India and Pakistan. Crowds of Muslim outsiders suddenly arrived in his village, ordering his family to convert to Islam or die. His father, dying, shouted, “Run, Milkha, run!” He raced for the forest, crying.There followed a time when Singh hopped trains as a refugee, shoeless and starving. Eventually the army took him on. There he discovered running of a new kind, with coaching, races over set lengths, and prizes. The first race he won rewarded him with a daily glass of milk.As a result, Singh began the hard, necessary work, six hours a day. He pushed his body to the limit out of pride—and for India. His iron discipline finally paid off. In 1960, he was invited to compete against Pakistan’s champion runner. At first, Singh refused to go since his childhood home was there and now he was still covered in his mind with the blood of his family. However, the moment Singh crossed the border, to his surprise, he was welcomed with flags and flowers. When he won his race, the then Pakistani prime minister said, “Pakistan bestows on (授予) you the title of The Flying Sikh. ” Despite everything that had happened, Singh had two countries.56. Milkha Singh _________ at the 1958 British Empire and Commonwealth Games.A. narrowly won the 400-meter dashB. broke the world record for the 400 metersC. was already a household name before the 400-meter dashD. had little confidence in himself before the 400-meter dash57. Put the following things in the time order of their appearance in Singh’s life.①milk as a prize②gold medal③school education ④the title of The Flying SikhA. ①②③④B. ①③②④C. ③①②④D. ③①④②58. Singh’s success as an athlete lies in his _______________.A. good luckB. rare talentC. constant effortD. patient coaches59. What is the best title of the passage?A. War and PeaceB. Lifelong RunningC. A Fierce CompetitionD. Running for Education(B)If you have an investment portfolio (投资组合) of $500,000 or more, get...______________________________________________________________________________ About Fisher InvestmentsFisher Investments is a moneymanagement enterprise servingover 85,000 clients as well aslarge institutional investors. * Wehave been managing portfoliosthrough bull and bear markets forover 40 years. Fisher Investmentshas managed over $169 billion inclient investments. *_______________________________________________________________________________60.If Mike is considering developing a tax-efficient retirement strategy, which tip can he turn tofor reference?A.Tip #10.B. Tip #23.C. Tip #40.D. Tip #85.61.What is “Fisher Investments”?A.An app.B. A book.C. A website.D. A company.62.What is the main purpose of this passage?A.To give investment advice to anyone planning to retire.B.To provide a free guide on retirement planning to everyone.C.To seek potential customers who are interested in retirement planning.D.To offer a special bonus report on maximizing Social Security benefits for retirement.(C)A baby born today will be thirty-something in 2050. If all goes well, that baby will still be around in 2100, and might even be an active citizen of the 22nd century. What should we teach that baby to help them survive and flourish in the world of 2050 and beyond? What kind of skills will they need in order to get a job, understand what is happening around them, and navigate their tough life?At present, too many schools across the world focus on providing pupils with a set of predetermined skills, such as writing computer code in C++ and conversing in Chinese. Yet since we have no idea how the world and the job market will look in 2050, we don’t really know what particular skills people will need. We might invest a lot of effort in teaching kids how to write in C++ or to speak Chinese, only to discover sooner or later that AI will have been able to code software far better than humans, and that a new translation app will have enabled you to conduct a conversation in almost flawless Mandarin, Cantonese or Hakka, even though you only know how to say ni hao.So what should we be teaching? Many experts argue that schools should downplay technical skills and emphasize general-purpose life skills: the ability to deal with change, to learn new things, and to preserve your mental balance in unfamiliar situations. In order to keep up with the world of 2050, you will above all need to reinvent yourself again and again.To succeed in such a demanding task, you will need to work very hard on getting to know your operating system better—to know what you are and what you want from life. This is, of course, the oldest advice in the book: know thyself. This advice was never more urgent than in the mid-21st century, because unlike in the days of Laozi or Socrates, now you have serious competition. Coca-Cola, Amazon and Facebook are all racing to hack you.Right now, the algorithms (算法) are watching where you go, what you buy, and who you meet. Soon they will monitor all your steps, breaths and heartbeats. They are relying on big data and machine learning to get to know you better and better. And once these algorithms know you better than you know yourself, they could control and manipulate (操纵) you. In the end, authority will shift to them.Of course, you might be perfectly happy giving up all authority to the algorithms and trusting them to make decisions for you and for the rest of the world. If, however, you want to maintain some control over your personal existence and over the future of life in general, you have to run faster than the algorithms. To run fast, don’t take much luggage with you. Leave all your illusions(幻想) behind. They are very heavy.63.What does the underlined word “downplay” in paragraph 3 most probably mean?A.Give too much emphasis on something.B.Make people think that something is less important.C.Offer your reasons why something is right or wrong.D.Decide something in advance so that it does not happen.64.According to the article, ___________ plays a vital role in children’s bright future.A.imaginationB. adaptabilityC. self-disciplineD. a good sense of balance65.It’s important to know our operating system because ___________.A.if we don’t, algorithms will hack all our devices.B.it is an essential skill for us to succeed in the world of 2050.C.we need to learn how algorithms work and make full use of them.D.we need to outrun algorithms to keep some control over our personal life.66.The article mainly talks about _________.A.the importance of knowing yourselfB.the threats and dangers of technologyC.what kind of skills we might need in the futureD.some potential benefits algorithms would bring to humankindSection CDirections: Read the following passage. Fill in each blank with a proper sentence given in the box. Each sentence can be used only once. Note that there are two more sentences than you need.A.Tailor Vitamin C intake to your weight.B.The subjects who couldn’t perform this had a higher risk of death.C.Vitamin C supplements are always safe and effective for everyone.D.Regular exercise can improve your balance and reduce the risk of falls.E.Both are harmless and don’t require treatment unless their appearance is an issue.F. But these products can contain a large amount of salicylic acid (水水水) and could leave youwith permanent scars.News From TheWorld of MedicineThe balance challengeCan you stand on one leg for ten seconds? This question could help doctors assess the overall health of their middle-aged and older patients, argues a Brazilian-led study published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine. (67) ____________________ During a follow-up period of seven years, the researchers drew the above conclusion after accounting for basic factors like age and sex.Besides causing falls, poor balance can also signal underlying medical issues, such as declining eyesight or nerve damage caused by diabetes (糖尿病). Much like grasp strength and walking speed, balancing ability doesn’t tell the whole story of your health, but it’s a useful clue.Don’t remove skin tags and moles yourself.Two of the most common types of skin spots among adults are dark spots known as moles and the growths known as skin tags. (68) ____________________In some places, mole-and skin-tag removal kits are sold for home use. (69) ____________________ US FDA recently issued a warning about these kits after receiving reports about consumers who had injured themselves. You’re better off visiting a dermatologist, who are experts in treating skin diseases. Plus, they can perform the all-important screening for skin cancer.(70) ____________________Researchers from New Zealand recommend a 60-kilogram person consume 110 milligrams of vitamin C per day through a balanced diet, while someone weighing 90 kilograms needs 140 milligrams. That is to say, when taking vitamin C, it’s best to take your weight into account. Eating foods like oranges—which contain on average 70 milligrams of vitamin C each—can really help.IV. Summary WritingDirections: Read the following passage. Summarize the main idea and the main point(s) of the passage in no more than 60 words. Use your own words as far as possible.71.A Montessori EducationThere are now at least 60,000 schools across the world using the Montessori method. There are different kinds of Montessori schools, but certain fundamental principles have remained the same.One is the idea of teachers encouraging the children to complete the activities with as little adult involvement as possible. Take the Ecoscuola Montessori on the Italian island of Sicily. At the school, there is a subject called “Practical Life”. It involves real-life practical tasks, such as serving drinks to their classmates. For safety, teachers would take charge of boiling the water, but the children would play active roles in cleaning the work surface and then presenting the drinks to others. “During breakfast and lunch, they are also self-directed, taking it in turns to lay the tableand serve their classmates,” says Miriam Ferro, the headteacher of Ecoscuola.The method encourages not only independence, but also cooperation. Children of different ages are taught in the same classroom, so that the six-year-olds, for example, can help the three-year-olds. In addition, each session is three hours long so as to allow the children to bury themselves in what they are doing. The learning materials are also designed for being handled and explored with all the senses. For example, letters and numbers are made of sandpaper, which the child can trace with their finger.This concept may sound sensible. But does it bring about any tangible(实际的) benefits, beyond those seen in a typical classroom?Angeline Lillard, a professor of psychology, found some benefits for children’s development while looking at a Montessori school in Milwaukee, in the United States. Analyzing their progress at age five, she found that the children tended to have better literacy, numeracy, executive function and social skills, compared to those who had attended the other schools. And at age 12, they showed better story-telling abilities.V. TranslationDirections: Translate the following sentences into English, using the words given in the brackets.72.你要学会用具体的例子来更清晰地阐述你的观点。

Unit1Explain in your own words the following sentences.1.Our big old house had seen the joys and sorrows of four generations of our family.2.I planted these roses a long time ago before your mother was born.3. Many young men left home to fight against fascists.4.Take the first friendly greeting and always keep it deep in your heart.1.When I was ten I suddenly found myself faced with the anguish of moving from the only home.2.…they all share the same characteristic: sadness.3.…in that place in your heart where summer is an everlasting season.4.Don’t ever let yourself overcome by the sadness and the loneliness of that word.5.T ake that special hello and keep it in your mind and don’t ever forget it1.我十岁那年突然要搬家从我唯一知道的家搬走心中痛苦万分.2.我们似乎有许多不同的方式说再见但它们都有一个共同之处那就是令人感到悲哀.3.有一天一场可怕的战争爆发了我的儿子就像许许多多的儿子离乡背井与极大的邪恶战斗去了4.我在自己的心灵深处搜寻那些构成我们友谊的特殊感情1.He has prepared answers to the questions that he expects to confront during the interview.2.His sad story touched us so deeply that we nearly cried.3.The two of them are walking hand in hand along the riverbank, chatting and laughing.4.When he heard the exciting news, tears of joy welled up in his eyes.5.People from Shanghai can understand Suzhou dialect with ease, for Shanghai dialect and Suzhou dialect have much in common.6.Henry and his wife are looking into the possibility of buying a new house within three years. 7He finally gave in to his daughter’s repeated requests to further her education abroad.8.We locked all our valuables away before we went on holiday.9.Although we have parted from each other, I hope that we’ll remain good friends and that wewill care for and help each other just as we did in the past.10.At that critical moment, the army commander summoned all the officers to work out new strategies and tactics which would make it possible to conquer the enemyUnit31.A gracious manner adds great splendour to your image.2.I dare say the note my guest sent me didn't take long to write.3.The simple phrase "Excuse me" made most of your irritation disappear.4.Being punctual has always been considered a virtue, both in the past and at present; it has not become outdated.5You shouldn't accept the other person's presence without thinking how much it means to you.6.Good manners can be communicated from one person to another.1.become different from what it should be like2.displaying gratitude by waving a hand or nodding the head; move out onto the main road3.be of great significance4.who receives the thank-you remark5.produce a far-reaching effect6.practice good manners1. 譬如,我在纽约就看到这样的差别与我20多年前刚搬来时大不相同了:人们蜂拥走进电梯,却没有让电梯里面的人先出来;别人为他们开门时,从来不说“谢谢”;需要同事给他们递东西时,从来不说“请”;当其他开车人为他们让道时,也从不挥手或点头表示谢意。

诺贝尔名言名句经典语录1. "The greatest use of life is to spend it for something that will outlast it." - Alfred Nobel2. "If I have a thousand ideas and only one turns out to be good, I am satisfied." - Alfred Nobel3. "Contentment is the only real wealth." - Alfred Nobel4. "Hope is a good breakfast, but it is a bad supper." - Alfred Nobel5. "The surest way to remain poor is to be an honest man." - Alfred Nobel6. "The most beautiful gift of nature is that it gives one pleasure to look around and try to comprehend what we see." - Alfred Nobel7. "Courage is a virtue that can turn fear into an opportunity for development." - Alfred Nobel8. "It is the heart that makes a man rich. He is rich according to what he is, not according to what he has." - Alfred Nobel9. "Patience and perseverance have a magical effect before which difficulties disappear and obstacles vanish." - Alfred Nobel10. "A little bit of science distances you from God, but a lot brings you nearer to him." - Alfred Nobel11. "One can say of figuratively that figures don’t lie, but it is a fact that the most careful consideration of figures often does not tell the whole truth." - Alfred Nobel12. "Truth is a jewel which is found in very few hands; while the pleasuresof falsehood are spread like a weed over the whole earth." - Alfred Nobel 13. "The day has ended, and the sun has set; but the mind has not." - Alfred Nobel14. "In the house which I hope for in heaven, there are many mansions. I will ask for one close to my friends, and there we shall be together again." - Alfred Nobel15. "Progress would not have been the rarity that it is if the early food had not been the late poison." - Alfred Nobel16. "I have long been firmly convinced that in our material world the mass is everything and individual thought of little value, whereas our thinking, overemphasized and overrespected, is the greatest obstacle to material progress that exists." - Alfred Nobel17. "The real potential of the Nobel Prize is to take the focus in humanitarian contests off individuals and placed it on the needs of humanity." - Alfred Nobel18. "Happiness is the meaning and the purpose of life, the whole aim and end of human existence." - Alfred Nobel19. "The two poles of life are:Belief and a lack of belief.One side can't live without hope.The other side can't live without allegiance." - Alfred Nobel20. "Peace is the natural effect of trade." - Alfred Nobel21. "Where there's peace, there's prosperity and abundance." - Alfred Nobel22. "Wealth does not bring about happiness, but rather the hope for wealth." - Alfred Nobel23. "Science alone of all the subjects contains within itself the lesson of the happiness of the acquisition of knowledge." - Alfred Nobel24. "Prosperity is measured not by the amount of silver and gold a man has, but by how well his actions benefit others." - Alfred Nobel25. "A home with a few loving friends is better than an ornate mansion inhabited by a lone individual." - Alfred Nobel26. "A teacher in every home, a book in every hand, and a pen in every field are the arrows of light that will one day alleviate the darkness of ignorance." - Alfred Nobel27. "Laws are like spider-webs which, if anything small falls into them they ensnare it; but if anything big falls into them, it breaks through and escapes." - Alfred Nobel28. "The individual has come to set very little store by belief, and lets much negative influence in the issue of conscience, to alleviate their suffering; and their standards often tend to shift according to the situation."29. "No one who has come into contact with humanity and civilizationhas been touched by it and has not been affected by it." - Alfred Nobel 30. "One's duty is to act without being moved by the moral doubt and when such action is undertaken the responsibility for it is on the individual who acts." - Alfred Nobel31. "It is for humans to search and, if they ever find it, to support the truth." - Alfred Nobel32. "Humanity is waiting and hoping for the implementation of wisdom; those times feel distant. But humanity waits for something that's connected and established." - Alfred Nobel33. "The sacred rights of man are not to be objects of omission, if not of utmost importance." - Alfred Nobel34. "The aim of life is preservation of the species through procreation, and excelling through production." - Alfred Nobel35. "If I consider what's presented on Earth, it makes me feel like the luckiest man in the world." - Alfred Nobel36. "I'm often encroached on by the desire to absolve myself from the crimes that benefit me, even if they are not of my making." - Alfred Nobel37. "When I consider the colossal importance of superior men and PHD holders in the 21st century, something extraordinary becomes apparent." - Alfred Nobel38. "Peace is synonymous with property. Property is an offshoot ofpersonal accomplishments. It is compared more to science which works to augment human capability, and for the enrichment of labor." - Alfred Nobel39. "Duty is on man and man will have no excuse for shunning this duty." - Alfred Nobel40. "A thinking individual is bound to err. There are moments when one is moved by a deep desire to undo that which has been done mistakenly." - Alfred Nobel41. "Purpose alone cannot drive the impulse toward such a goal as goodness and truth are." - Alfred Nobel42. "We are told that knowledge is itself an end, but what's the use the unlimited knowledge avails?" - Alfred Nobel43. "Even as I lay close to my haven of rest, my thoughts will traipse the world tirelessly, searching for stronger and more unassailable liberty for those who live in it." - Alfred Nobel44. "Only once humans ascertain the loathsome damage of hatred and wish for peace and love to conquer all will they fully understand love and peace." - Alfred Nobel45. "The desire to wade in others' sea of agony was the last thing I anticipated during my life in the grand world." - Alfred Nobel46. "There are those who are often guilty and experience moralconfusion, those who are indifferent to the quagmire of disgrace, but happiness and satisfaction aren't to be found amongst them." - Alfred Nobel47. "Should it fart with knowledge, or should we act detached? The choices set forth by the future are uncertain, and only time can reveal the correct one." - Alfred Nobel48. "What a man may assume and what he may accomplish are different things." - Alfred Nobel49. "I despise with all my heart the devilish practice of attacking the reputation of a fallen foe to win kinship with the living." - Alfred Nobel 50. "A sad, tragic tribulation I regard it, and not because my fall prevails, but because my tarnish is mistaken." - Alfred Nobel51. "T o create is to innovate. We must endeavor to produce, laboring for our coexistence and with thought and action trim the outcome to uplift the essence of life." - Alfred Nobel52. "The good-hearted who, with a clear conscience, are selfless in their quest, remain strangers to sorrow whether in heaven or on Earth." - Alfred Nobel53. "The day has ended; it is no more. But my mind? It is never so." - Alfred Nobel54. "While the material temptations of the world should not exceed our expectations, the celestial aspirations of an afterlife ought to humble us."- Alfred Nobel55. "Only the sound of a heart that yearns to live can match the voice of a heart that's found love." - Alfred Nobel56. "T o be superior to all that is around us is the height of our creation and that toward which every soul strives." - Alfred Nobel57. "Arriving to bring forth, and bringing forth to preserve and repair." - Alfred Nobel58. "The awarding of the Nobel Prize can never be motivated byself-interest. It should always have the aim to improve humanity." - Alfred Nobel59. "No economics without Peace." - Alfred Nobel60. "The powerful have no right to cause suffering to others just because they possess the means to effectuate such suffering." - Alfred Nobel。

英语词汇迷宫游戏教案设计Title: English Vocabulary Maze Game Lesson Plan。

Introduction:The English Vocabulary Maze Game is a fun and interactive way for students to learn and review English vocabulary words. This lesson plan is designed for intermediate level students and can be adapted for various age groups. The game not only helps students improve their vocabulary, but also encourages teamwork and critical thinking skills.Objective:The objective of this lesson is for students to review and reinforce their English vocabulary in a fun and engaging way. By participating in the Vocabulary Maze Game, students will be able to identify and understand the meanings of various English words, while also practicingtheir reading and comprehension skills.Materials:Whiteboard or chalkboard。

Markers or chalk。

Vocabulary word cards。

获奖用英语怎么说获奖英语说法1.win a prize2.be rewarded获奖的相关短语获奖情况Awards ; Awarding ; Honors and Awards ; Prize of History获奖经历Scholarship and Awards ; honor ; Winning experience ; award winning experience获奖作品Awards ; Prize-winning works ; The award-winning works ; Winning曾经获奖The award-winning ; Previous prize ; Once award获奖建筑Awarded Architecture获奖工程award winning works ; Award-winning project获奖电影an award-winning film获奖作文Award Winning Composition获奖通知Notification of Award获奖的英语例句1. The school has won awards for its pioneering work with the community.这所学校因其针对该社区具有开创性的而获奖。

2. There is no magic formula for producing winning products.获奖电影的制作没有捷径可取。

3. He had been on the Nobel Prize committees list of possibles.他在诺贝尔委员会列出的获奖候选者名单之列.4. the award-winning TV drama获奖电视剧5. It was altogether owing it to himself that James won the prize.詹姆斯获奖完全是靠自己的努力.6. He hopes from his very heart that he will win a prize.他满心希望获奖.7. I am not the only person that has won the prize.获奖的不单是我一个人.8. He won a prize for good behaviour at school.他因在校的表现好而获奖.9. She begrudged her friend the award.她嫉妒她的朋友获奖.10. What sticks in my throat is that I wasnt able to win the trophy.令我耿耿于怀的是自己没能获奖。

Unit 6 【B卷(能力提升)】一、单项选择1.—We had an excellent physics lesson. We watched an experiment which ________ in space by Wang Yaping.—Wow, that sounds great. I will learn it on the Internet.A.teach B.taughtC.is taught D.was taught2.Not only my friends but also I ______ interested in football and Messi is our favourite star.A.be B.amC.is D.are3.—It’s said that Qin Wenjing in Nanya Middle school ________ the prize for The Most Beautiful Student in China in 2016.—Yes. We are proud of her!A.was awarded B.is awarded C.is awarding4.—It is much faster to drive from the south to the north now.—Yes, a new high way ________ last October.A.is finished B.was finished C.has been finished5.A good book is inspiring. It can make readers enjoy the ________ of reading.A.please B.pleasantC.pleasure D.pleased6.A number of new houses ________ in Wenchuan last year.A.built B.are builtC.were built D.will be built7._________ the new park _________ in Shanghai two years ago?A.Does; build B.Did; buildC.Is; built D.Was; built8.—________ Ben ________ Bob is in good health recently.—I think they both need to take more exercise.A.Neither; nor B.Both; and C.Either; or D.Not only; but also9.Brian is an honest boy. I have no reason to ________ what he said.A.introduce B.doubt C.believe D.know10.Not only my father but also I ________ good at playing basketball.A.am B.is C.are D.be 11.—Dad, the lock of my room is broken.—I’ll ________ it. I just have finished my work.A.repair B.satisfy C.divide D.break 12.The man felt terrible. He ________ by doctors.A.give first aid B.gave first aidC.was given first aid D.is given first aid13.What a bad ________! I can hardly stand it even though my nose is not sensitive.A.smell B.sound C.look D.taste 14.We _______ spend too much time in watching TV.A.told don’t B.told not toC.were told not to D.were told to not15.Each of us ________ a new schoolbag last week.A.gave B.is givenC.was given D.were given二、补全对话7选5根据对话情景选择合适的选项补全对话。

诺贝尔文学奖作文素材最新版The Nobel Prize in Literature is one of the most prestigious awards in the world. It is awarded to an author, whether they are a novelist, poet, or playwright, who has produced outstanding work in the field of literature. 诺贝尔文学奖是世界上最负盛名的奖项之一。

它授予那些在文学领域取得杰出成就的作家,无论他们是小说家、诗人还是剧作家。

The prize has been awarded since 1901 and is considered by many to be the ultimate recognition of literary talent and contribution to humanity. The award is not only a recognition of the author's work, but also a celebration of the power of literature to inspire, provoke thought, and bring about change in the world. 该奖项自1901年设立以来,被许多人认为是对文学才华和对人类贡献的最终认可。

这个奖项不仅是对作家作品的认可,也是对文学的力量的庆祝,它能激励、引发思考,并为世界带来改变。

Each year, the Nobel Committee carefully selects the recipient of the Literature Prize. The decision-making process is rigorous and the Committee seeks to award those who have made a significant impact on the literary world and contributed to the promotion of culturalunderstanding and peace. 每年,诺贝尔委员会都会仔细挑选文学奖的获得者。

高中英语阅读理解细节与推理结合题40题1. What can we know from the passage?A. The author is a famous writer.B. The story happened in a modern city.C. There are many animals in the forest.D. The main character has a special ability.答案:C。

本题主要考查对文章细节的理解。

文章中明确提到了森林里有很多动物,A 选项中作者是否是著名作家文章未提及,B 选项故事发生的地点文章没有具体说在现代城市,D 选项关于主角有特殊能力文章也没有明确表述。

2. It can be inferred from the passage that _.A. the hero will win in the end.B. the villain is very powerful.C. there will be a big battle.D. the story has a happy ending.答案:B。

根据文章中对反派的描述,可以推断出反派很强大,A 选项英雄最终是否会胜利文章未给出明确信息,C 选项是否会有一场大战也不确定,D 选项故事结局是否快乐文章也没说。

3. According to the passage, which of the following is true?A. The main character is very brave.B. The weather is always sunny.C. There are many flowers in the garden.D. The old man is very kind.答案:D。

从文章中对老人的描述可以看出老人很善良,A 选项主角是否勇敢文章没有明确说,B 选项天气是否总是晴天文章未提及,C 选项花园里有很多花文章没有具体提到。

获得诺贝尔奖的英文作文英文:Winning the Nobel Prize is a dream that many scientists and scholars aspire to achieve. It is one of the highest honors in the world and is a recognition of outstanding contributions to humanity in various fields such as physics, chemistry, medicine, literature, peace, and economic sciences.I remember the day when I received the news that I had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics. I was in complete disbelief at first, thinking it was a joke. But as thereality sank in, I was overwhelmed with emotions. It was a moment of pure joy and validation for all the years of hard work and dedication I had put into my research.The Nobel Prize not only brings prestige and recognition, but it also comes with a sense of responsibility. As a Nobel laureate, I am now in a positionto influence and inspire the next generation of scientists.I have the opportunity to use my platform to advocate for important causes and contribute to the betterment of society.Receiving the Nobel Prize has also opened up doors for me to collaborate with other brilliant minds in my field.It has given me the opportunity to exchange ideas and work on projects that have the potential to make a real impacton the world. I am grateful for the connections and opportunities that have come my way as a result of this prestigious award.Overall, winning the Nobel Prize has been a life-changing experience for me. It has given me a sense of fulfillment and purpose, and it has motivated me tocontinue pushing the boundaries of knowledge and innovation.中文:获得诺贝尔奖是许多科学家和学者梦寐以求的荣誉。

给一个名人颁布奖的英语作文英文回答:It is with great honor and admiration that we gather here today to pay tribute to an extraordinary individual whose contributions have left an indelible mark on our society. This esteemed celebrity has not only captivated hearts and minds through their exceptional talent but has also used their platform to inspire, uplift, and make a meaningful difference in the world.Throughout their illustrious career, this luminary has consistently demonstrated unwavering commitment to excellence, pushing the boundaries of their craft and setting new standards. Their passion for their work is evident in every performance, every interview, and every interaction they have with others. Their tireless dedication and unwavering determination have served as a source of inspiration for countless aspiring artists and performers.Beyond their professional achievements, this celebrity has also been a vocal advocate for important causes, speaking out against injustice, promoting equality, and using their influence to raise awareness about critical issues facing our planet. Their compassion and empathy extend far beyond the stage or screen, as they have dedicated themselves to philanthropic endeavors, supporting organizations that work to improve the lives of others.The impact of their work has been profound, not only on the entertainment industry but also on the broader cultural landscape. They have inspired a new generation of artists and performers, challenged societal norms, and sparked important conversations about the human experience. Their contributions to the arts and to society at large have earned them widespread recognition and admiration.Tonight, as we gather to celebrate their achievements, we also recognize the profound impact they have had on our lives. Their work has brought joy, laughter, and thought-provoking insights into our homes and hearts. They haveshown us the power of art to transcend boundaries, unite people, and inspire us to strive for a better world.For all that they have given us, we are eternally grateful. Please join me in giving a thunderous round of applause to our esteemed honoree, a true legend and an inspiration to us all.中文回答:今天,我们怀着崇高的敬意和钦佩的心情齐聚一堂,向一位杰出的人物致敬,他们的贡献在我们的社会中留下了不可磨灭的印记。

prize-awarding sessionThe prize-awarding session is one of the mostanticipated events in the world of academia and research. It is a culmination of years of hard work, dedication, and ingenuity that has led to groundbreaking discoveries and advancements in various fields.As the day of the prize-awarding session approaches, the excitement and anticipation among the finalists and their colleagues continue to grow. From scientists and researchers to writers and artists, everyone is eager to witness who will take home the coveted prize.The session begins with a grand ceremony, where distinguished guests, officials, and supporters gather to honor the finalists. The ceremony is marked by speeches, tributes, and performances that celebrate the outstanding achievements of the nominees.As the ceremony progresses, the tension in the airstarts to build, and the audience waits with bated breath for the announcement of the winners. The judges finally take the stage, and after a few words of congratulations and appreciation, they announce the names of the winners.The room erupts in applause as the winners walk up to the stage to receive their awards. Emotions run high as they give their acceptance speeches, thanking their mentors, colleagues, and loved ones for their support and encouragement throughout their journey.For the winners, the prize-awarding session is a moment to cherish and remember for a lifetime. It is a recognitionof their hard work, determination, and passion for their areas of expertise. For the audience, it is a reminder of the transformative power of education, research, and creativity.In conclusion, the prize-awarding session is an incredible celebration of human achievement and a testament to the power of imagination and innovation. It provides a platform for recognition and inspiration, inspiring future generations to strive towards excellence in their fields of interest.。