REQUIREMENTS AND BARRIERS TO ADOPTION OF LAST PLANNER COMPUTER TOOLS

Hyun Jeong Choo1 and Iris D. Tommelein2

ABSTRACT

The Last Planner methodology has been applied to construction and design. These efforts have resulted in the development of computer programs (WorkPlan and DePlan) that guide production units in creating reliable work plans. One of these programs was extended to include distributed planning and coordination and space scheduling capabilities as well (WorkMovePlan).

During and after the development of these tools, LCI member companies used them and provided valuable feedback. Some of these companies have developed in-house spreadsheet applications to meet their own particular needs. These beta-testers were familiar with the Last Planner concepts, which allowed them to make suggestions based on their conception of the Last Planner methodology.

This paper reports on the feedback from the beta-testers of WorkPlan, DePlan, and WorkMovePlan. This feedback provided a foundation for further specifying requirements for the Last Planner computer tools. The paper also discusses barriers to adoption of Last Planner tools in companies that are new to lean construction and in companies that have already started lean transformation. These findings not only assist in improving existing tools but also reveal new areas for computer tool implementation.

KEYWORDS

Last Planner methodology, lean construction, design management, construction management, production management, computer tools, distributed planning, coordination, planning, scheduling, space scheduling, WorkPlan, DePlan, WorkMovePlan, work package, assignment.

1Ph.D. Candidate, Constr. Engrg. and Mgmt. Program, Civil and Envir. Engrg. Dept., 215 McLaughlin Hall #1712, Univ. of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, choohj@https://www.doczj.com/doc/1a15650011.html,

2Professor, Constr. Engrg. and Mgmt. Program, Civil and Envir. Engrg. Dept., 215-A McLaughlin Hall #1712, Univ. of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, tommelein@https://www.doczj.com/doc/1a15650011.html,

INTRODUCTION

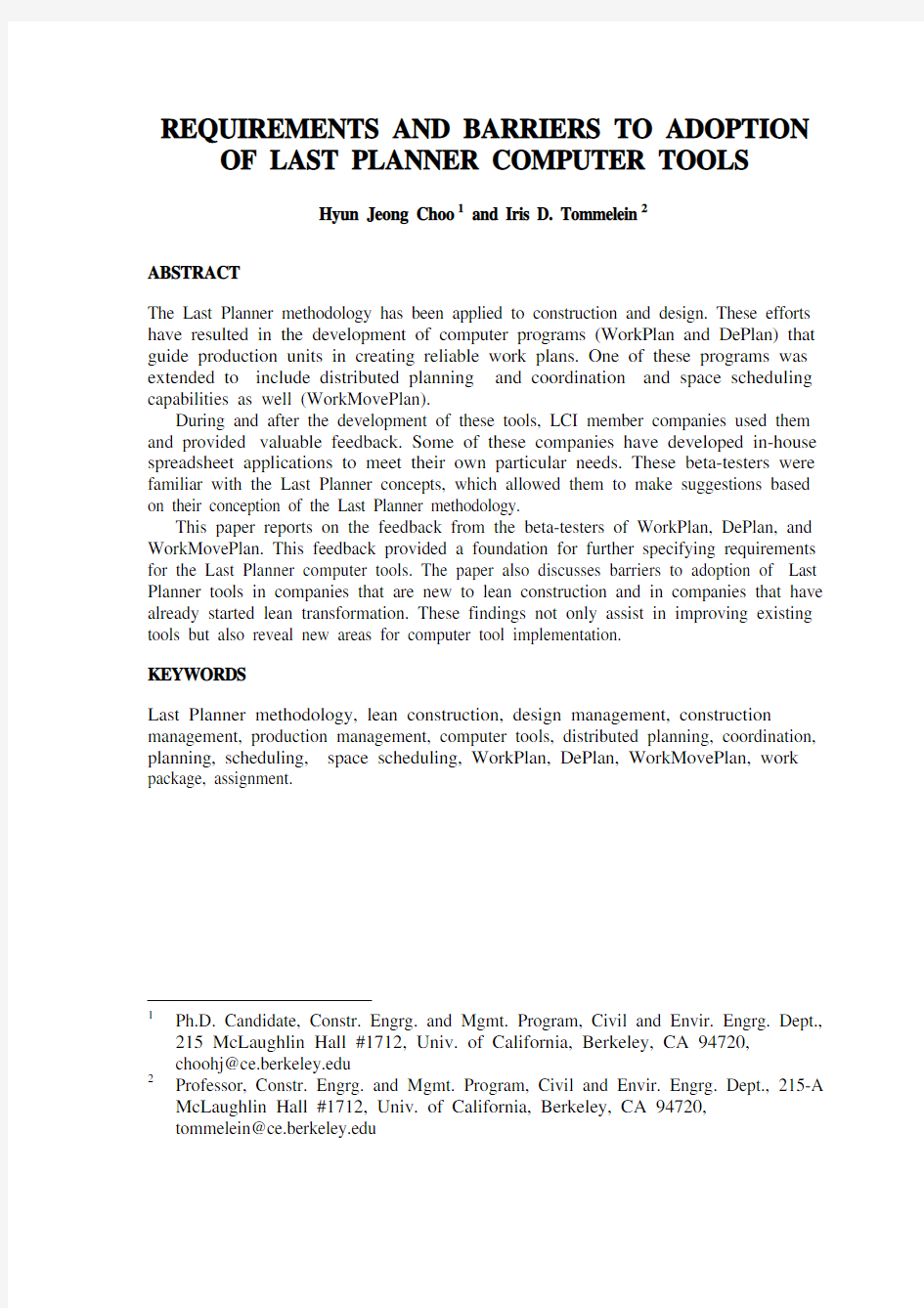

Application of the Last Planner methodology to construction and design has resulted in the development of WorkPlan (Choo et al. 1998, 1999) and DePlan (Hammond et al. 2000), respectively (Figure 1). These tools guide production units in following the Last Planner methodology to create reliable work plans.

Figure 1: Last Planner Software including WorkPlan and WorkMovePlan WorkPlan is for specialty contractors to develop weekly work plans. WorkPlan is a stand-alone program but it also allows for production units working on construction projects to import basic schedule information, such as a list of activities, precedence relationships, etc. from Microsoft Project (Microsoft Corporation 2000). DePlan combines WorkPlan

with ADePT’s (Austin et al. 1999) ability to represent design process models, perform dependency structure matrix analysis, and develop design programs for the overall projects and individual disciplines. DePlan guides production units working on design projects to import schedule information from ADePT.

WorkPlan has been extended into WorkMovePlan (Figure 1), which includes capabilities for distributed planning and coordination and space scheduling (Choo and Tommelein 1999, 2000a, 2000b). The distributed planning and coordination capabilities allow production units to increase the reliability of their plans by sharing work package, space scheduling information, and constraint information. The space scheduling capabilities allow each planner to explicitly allocate space, including workspaces, laydown areas, storage areas, and access paths.

After the development of WorkPlan, DePlan, and WorkMovePlan, beta-testers from four member companies of the Lean Construction Institute (LCI) (Pacific Contracting, Barnes Construction, Oscar J. Boldt Construction, and Gowan Inc.) and academic institutions (Loughborough University in the U.K. and Universidad Catolica de Chile) provided feedback and recommendations on their use. The beta-tests took anywhere from one day to two months. The beta-testers knew the Last Planner methodology, especially the part related to weekly work planning. Some of them had developed in-house spreadsheet applications to support the Last Planner process given their own specific needs. These applications did not necessarily meet all their needs but they provided a temporary solution. However, the main advantages of these spreadsheet tools were simplicity of interface and ease of use. The beta-testers had wish lists expressing additional, desired features. Their feedback on our tools ranged from suggestions regarding adding and deleting fields in forms and reports (sometimes to make the form s and reports resemble their own), to changing how the tools should be used or what additional capabilities they should have (implementing their own wish lists). Having understood the Last Planner methodology and having been involved in creating their own tools allowed them to focus on making suggestions on how to improve the tools, rather than needing to be convinced to adopt the Last Planner process. However, their previous knowledge of the Last Planner prevented them from assessing how well this methodology was embedded and enforced in the tools. Enforcement would be particularly helpful to newcomers who are learning to follow the Last Planner methodology.

The real challenge for the tools is to be accepted by both newcomers as well as champions of the Last Planner. Whether the tools could be used to introduce newcomers not only to the Last Planner methodology but also to lean construction remains to be seen. This paper summarizes the responses and feedback received from the beta-testers, it further specifies requirements for the Last Planner computer tools, and it describes barriers encountered when applying these tools.

FEEDBACK ON IMPLEMENTATION

During the development of WorkPlan, Glenn Ballard (developer of the Last Planner) and Todd Zabelle of Pacific Contracting (a specialty contracting firm) provided valuable input to the authors regarding the planning process as well as the functional requirements for the development of software. As the Last Planner methodology itself was (and still is) evolving during the development, WorkPlan took on many different forms as well.

W ORK P ACKAGE VS. A SSIGNMENT

A key decision to be made during the first implementation phase is whether or not to adopt “work package” as a scheduling unit. The primary reason for adopting work package rather than a more detailed, smaller unit of work, was to prevent general contractors from micro-managing specialty contractors. The specialty contractor’s concern was “if we give them too detailed a schedule, we end up creating smaller milestones for ourselves and lose the flexibility to do the job as we would like to.” Although the term work package has not survived the conceptual evolution of the Last Planner, it is still an intricate part of WorkPlan, DePlan, and WorkMovePlan.

A closer observation of the primary reason for adopting work package reveals its usefulness. The weekly work planning effort to manage production units was complicated by the need to report weekly work plans to general contractors. In order to prevent micro-management, creating big enough units of work to hide detailed processes seemed reasonable. However, if a work package is too big, it does not satisfy the sizing criterion of the Last Planner (Ballard 1997). It also makes managing a production unit less effective. This finding led to formulating an important requirement specifically for distributed planning and coordination: the size of work for work planning does not necessarily have to match the size of work for reporting. Consequently, WorkMovePlan (which tackles distributed planning and coordination—note that WorkPlan and DePlan do not) incorporates a hierarchical work package structure.

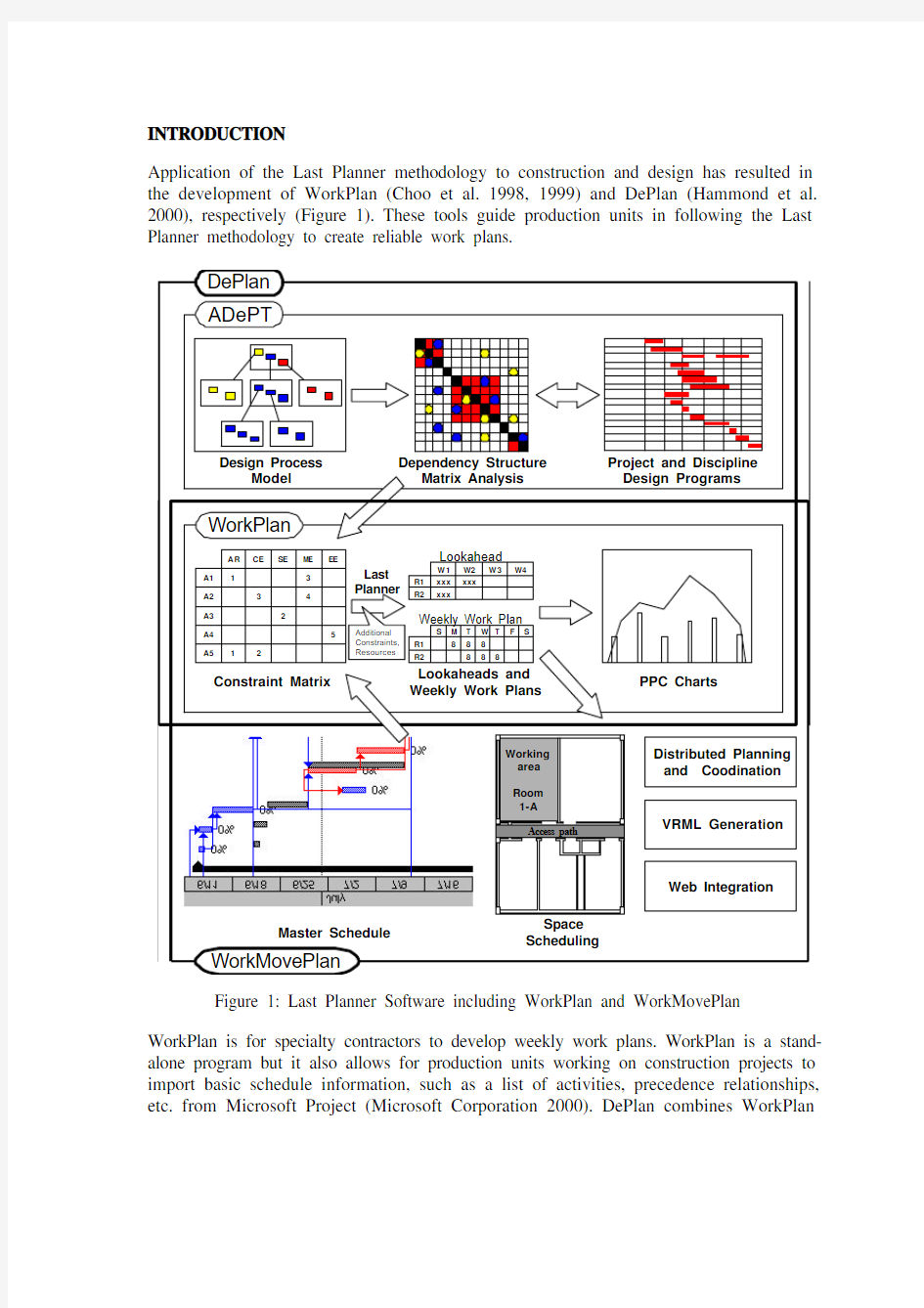

In the current Last Planner methodology, resource assignments are made at the assignment level. It is therefore necessary to maintain links between two distinctively-sized units of works, namely work packages and assignments. These links, shown in Figure 2, maintain the relationship between the project schedule and the production schedule. Work packages refer to work that is assigned (or contracted for) by a general contractor to a specialty contractor. The specialty contractor can then break these work packages down into one or more assignments using the Activity Definition Model (ADM). However, this breakdown may be made visible or invisible depending on the s pecialty contractor’s willingness to share that information. When the breakdown is made invisible, it is presented to the general contractor as aggregated data.

Figure 2: Relationship between work packages and assignments

Ballard (1997) uses lookahead schedules to link the project schedule to weekly work plans. However, maintaining an explicit link between these three requires effort. Different people use different tools to develop these schedules. Typically, project managers develop project schedules using CPM-based scheduling tools; superintendents develop lookaheads using either scheduling tools or spreadsheets; and specialty-contractor foremen develop weekly work plans using spreadsheets or mere crib sheets. Any of these may be done on a computer. Currently no single data repository or tool exists to support such different levels of scheduling by different people. A project manager who applied the Last Planner methodology to his project identified the need for explicit links: “We have convinced our subcontractors to tell us what they can do rather than give us an unrealistic schedule. However, one subcontractor is right now delaying our completion date. So we informed him that he was delaying the completion date and would be charged a penalty accordingly. However, he came back and told us that he could not be held responsible because he just did what he was told,

i.e., “tell us what you can do [according to the Last Planner concept: what is on

your weekly work plan and what is your workable backlog?].”

In the first week on the project, this subcontractor did not know the Last Planner and he submitted a schedule as usual showing what he should be doing, namely complete four walls in a week. He ended up completing only half of what he had said he was going to complete that week. So we sat down with him to develop the following week’s weekly work plan, with as aim to increase his planning reliability (PPC). He committed to completing two walls. However, it was unclear what effect this change would have on the total project duration until last week, when we updated the master schedule. It would be great if somehow the weekly work plans were linked to the master schedule.”

When we shared this case with other planners, the most common and immediate response was “The duration should have been set in the contract.” This contracting mentality does not create an environment where information can be shared freely. All too often, information regarding failure to meet a schedule then is withheld until the last moment, when it is too late to respond or inform others of the delays. In some cases, the schedule in the contract is purely for contracting purposes and it is never enforced. A project engineer on a building project presented this case:

“Completion of the building is going to be delayed by one subcontractor. They submitted a schedule to finish their portion of work within a month because that was the duration set forth by the owner’s master schedule. But there is no way they can finish that work in a month. They know it and we know it. So the schedule used for contracting sits in the cabinet and we use another schedule developed by our superintendent.”

Contracting is not an effective means to coordinate the work of specialty contractors. A hierarchical distributed planning system that effectively links project planning with production planning helps to effectively coordinate specialty contractors.

H OW T OOLS C AN B E U SED

Ballard (2000) and Fischer et al. (2000) report that most coordination-meeting time is currently spent on collecting information about the past and future, rather than on planning, i.e., figuring out the collective execution plan for the future. Some project participants are consciously trying to decrease meeting time spent on data collection.

On one project, the project manager (or the project engineer) talks to each specialty contractor in advance of the meeting, collects data, and types it into the scheduling program. The coordination meeting is then spent on informing others of the decisions made by each specialty contractor and identifying potential conflicts. Conflicts then can be resolved in separate, focused meetings involving only the affected parties. In this case, the coordination meeting is carried out at a relatively fast pace to keep all participants involved. To facilitate the meeting, a spreadsheet containing current and next week’s weekly work plans is projected onto a screen. This spreadsheet allows the participants to view the latest information, point out errors, and add and delete information as necessary. However, the project manager found that he was spending too much of his time inputting, copying, and pasting information from last week’s work plans to the next week’s work plans. Most of these activities have been automated in WorkMovePlan. The project manager and project engineer requested that WorkMovePlan be designed to support both, planning by a single planner and planning during coordination meetings.

Several project managers requested that the graphical user interface (GUI) of the tools resemble what they were used to seeing, i.e., a Microsoft Excel-like format rather than a complex form view. In response, a new GUI for the “Work Package Constraints” analysis screen (Figure 3) and other GUIs have been added. As the non-Excel-like view (Figure 4) is complementary rather than obsolete, both screens now co-exist in the program. In DePlan, the “Constraint Matrix Screen” (Figure 5) enables planners to see in a concise format the number of outstanding constraints for the whole project. Clicking on a number in a box brings up the detailed list of constraints (not shown). Similar changes were made to key interfaces, such as the “Resource Assignment Screen” (not shown). Where appropriate, old GUIs were replaced with this new Excel-like format.

Figure 3: New GUI for Work Package Constraint Analysis Screen

One project manager provided important feedback related to the distribution of information. He requested that once constraint analysis and weekly work planning is done, WorkPlan, DePlan, and WorkMovePlan would automatically categorize the information according to the responsible parties and then generate reports to send in electronic format or to print and hand out as hardcopies.

Figure 4: Non-Excel-like GUI for Constraint Analysis

Figure 5: Constraint Matrix Screen

He wanted to have an efficient way to distribute the constraints to each responsible party or person right after the coordination meeting. Specifically, he requested that the planner would be able to generate reports from the constraint list, categorized by work package and responsibility. The new buttons to generate these reports are shown in Figures 3 and 4. The “Constraint Report by Work Packages” (Figure 6) allows the planner to see all outstanding constraints for a single work package. The “Constraint Report by Responsibility” (Figure 7) prints out a separate page with outstanding constraints for each responsible party.

Many other suggestions related to additional fields were made, such as adding a responsible party to each work package and so on. Some suggested functions have not been implemented as either they exceeded the scope of our research or we determined them to be low in terms of implementation priority.

Figure 6: Constraints Report by Work Packages

Figure 7: Constraints Report by Responsibility (for responsible party BBB) REQUIREMENTS FOR LAST PLANNER TOOLS

Based on our experience in implementing and modifying WorkPlan, DePlan, and WorkMovePlan, we have identified several requirements for the Last Planner computer tools. These requirements are discussed next.

E FFECTIVE AND U NCOMPLICATED L AST P LANNER P ROCEDURE

It goes without saying that a Last Planner computer tool needs to be based on comprehensive understanding and effective translation of the Last Planner methodology. This methodology is based on a very different view of construction planning than the

view taken by traditional construction project management. It may take some time for some project participants, whether they work for the owner, engineering design firm, general contractor, specialty contractors, or vendors/suppliers, to change their traditional view of the industry.

C OORDINATION M EETING S UPPORT

Implementation of the Last Planner process relies heavily on the ability to collect information especially during the development of constraints, analysis of work package status, and formulation of reasons for failure. Information collection can occur either in a face-to-face meeting or in a distributed fashion. Regardless of how information is collected, coordination meetings will be helpful for project participants to get to know each other and establish a basis for communication, to identify and resolve conflicts, and to clear up vague items. In these meetings, the most up-to-date information needs to be available to the meeting participants in a format that they can easily recognize and interpret. Last Planner tools need to be designed to effectively support such coordination meetings.

E FFECTIVE I NFORMATION D ISTRIBUTION

Once all updates have been collected and processed, the latest information needs to be distributed either electronically or in hard-copy format. WorkMovePlan automatically synchronizes with other WorkMovePlans to ensure that every project participant has the latest information. WorkMovePlan also allows a planner to view the latest information on the web. This information is either pulled or pushed depending on the frequency of updates and their data formats. By contrast, in WorkPlan and DePlan, data needs to be sent either in electronic or in paper format. WorkPlan, DePlan, and WorkMovePlan already have many preformatted reports ready to be sent out or printed. What additional information needs to be distributed and in which form needs further study.

F AMILIAR U SER I NTERFACE AND D ATA S TRUCTURE

A familiar user interface and data structure will promote acceptance and avoid confusion when planners migrate from paper-based tools or other computer tools to Last Planner tools. As pointed out earlier, some project managers specifically asked that GUIs would look like Excel. Other project managers requested that reports would look exactly like the reports they have been using. Some but not all of these requests have been realized, depending on whether or not they met general needs. In terms of data structure, maintaining a level of detail for all information close to the level planners are used to seeing is very important, unless there is a strong reason to do otherwise.

I NTERFACE WITH L EGACY S YSTEMS

WorkPlan, DePlan, and WorkMovePlan are planning tools that are specifically designed to support the lookahead and weekly work planning process. The responsibility for master scheduling is left to CPM-based scheduling tools. However, in order to fully maintain data integrity between the project schedule and the production schedules, WorkPlan, DePlan, or WorkMovePlan, and CPM-based master scheduling tools need to work together.

Additionally, many companies have their own accounting system and are not keen on changing it in any way. Therefore, Last Planner tools must be able to interact with these systems as well. Other interfaces might include interfaces to a personnel database, an equipment maintenance database, document control tools, etc.

O THER R EQUIREMENTS

The requirements listed above are either very important or they are requirements specific to Last Planner tools. However, other generic requirements exist. For instance, computer tools should:

? be reliable, e.g., the software should not crash or compute erroneous results

? allow for collection of information once and at the source, then allow for re-use anywhere it is required

? synchronize and update information to represent only the latest information

? be able to archive and recall past information

BARRIERS TO ADOPTION

The construction industry has consistently been accused of being slow to adopt technological change. However, once a technology has been proven to deliver and accepted, industry use spreads widely. Examples are today’s common use in the United States of walkie-talkies, cellular phones, fax machines, Primavera Project Planner, and AutoCAD. Increasing numbers of PDAs are now seen at construction sites as well.

The use of Last Planner tools is closely related to the adoption of the Last Planner methodology. Currently, practitioners first adopt the Last Planner methodology, and then look for supporting computer tools. It remains to be seen whether the use of the tools, such as those presented here, can lead to the acceptance of lean construction principles with the Last Planner methodology in its broadest sense, encompassing front-end planning (Lean Construction Institute 1999, Ballard 2000) and lookahead planning (Ballard 1997, Tommelein and Ballard 1997) as well. Other researchers, including Chua, Jun, and Hwee (Chua et al. 1999, Jun et al. 2000), are also toying with computer implementations of the Last Planner methodology. We encourage others to do the same so that as a community we may speed up the practice of lean construction.

During an interview with a project manager and a superintendent of one of the largest contracting firms in California, it was clear that the notion of centralized control is still dominant in our industry. The superintendent said, “You always want to have more information than your subs, so that you have leverage over them.” This mentality is both naive and short sighted. The lack of transparency of information creates adversarial relationships. He also said, “We have a very detailed master schedule [with activity durations no more than 4 to 5 days], so we can keep tight control over the subcontractors.” When the project manager was asked to estimate their Percent Planned Complete (PPC, a concept in the Last Planner), he answered 35%. If that is indeed so, clearly, the superintendent’s “tight control” is not very tight. However, tight control is rarely criticized as being the source of the problem whereas the lack of specialty contractors’ abilities to execute as planned often is. Therefore, a “tighter control” is exercised.

A project engineer working on a construction project, which implemented the Last Planner methodology, expressed his frustration when trying to shift the subcontractors’ thinking away from centralized control to distributed control. He said that some subcontractors came back and said, “Don’t ask us what we can do, but just tell us what to do.” Where these views of construction management are predominant, acceptance of Last Planner tools will not be easy. However, he also commented that “Now they understand and they have accepted it.”

Transitioning from centralized control to distributed control is not easy. However, with the increasing specialization of specialty contractors and complexity of projects, and with the rapid advancements in information technology and communication infrastructure, the transition is well under way and it seems to be a matter of course.

CONCLUSIONS

The tools we have developed to implement the Last Planner methodology, namely WorkPlan, DePlan, and WorkMovePlan, have gone through several stages of modification from their inception until their current implementation, based on feedback from beta-testers. Between each stage, the requirements for Last Planner tools have become more clear. At the same time, the barriers to adoption have become better understood. These barriers are gradually being removed, with the spreading adoption of the Last Planner methodology, the increased acceptance of decentralized control, and the advancement of information technology. Further, deepened understanding of requirements and barriers will help in developing yet better specifications to enhance these tools.

It remains to be seen whether companies that are not on a lean journey can benefit from the Last Planner methodology as encapsulated in these computer programs, without first understanding and accepting the theory behind it. Many recent communication and computer tools do not require an explicit buy-in into any specific methodology. If the tools facilitate the adoption of the Last Planner methodology, the industry-wide practice of lean construction will grow even faster.

REFERENCES

Austin, S.A., Baldwin, A.N., Li, B., and Waskett, P.R. (1999). “Analytical Design Planning Technique (ADePT): programming the building design process.” Proc. of Institution of Civil Engineers, Structures and Buildings, 134, 111-118.

Ballard, G. (1997). “Lookahead Planning: The Missing Link in Production Control.” Proc.

5th Ann. Conf. Intl. Group for Lean Constr., Griffith Univ., Gold Coast Campus, Queensland, Australia. 13-25.

Ballard, H.G. (2000). “The Last Planner System of Production Control”, Ph.D.

Dissertation, School of Civil Engrg., Univ. of Birmingham, U.K., May, 192 pp. Choo, H.J. and Tommelein, I.D. (1999). "Space Scheduling Using Flow Analysis." Proc.

7th Ann. Conf. Intl. Group for Lean Constr., Univ. of Calif. Berkeley, CA, USA, 299-311. Available at https://www.doczj.com/doc/1a15650011.html,/~tommelein/IGLC-7/PDF/Choo&Tommelein.pdf

Choo, H.J. and Tommelein, I.D. (2000a). "WorkMovePlan: Database for Distributed Planning and Coordination." Proc. 8th Annual Conference of the International Group

for Lean Construction (IGLC-8), 17-19 July, held in Brighton, U.K., available at https://www.doczj.com/doc/1a15650011.html,/~tommelein/IGLC8-Choo&Tommelein.pdf

Choo, H.J. and Tommelein, I.D. (2000b). "Interactive Coordination of Distributed Work Plans." Proc. Construction Congress VI, ASCE, 20-22 Feb., Orlando, Florida, 11-20. Choo, H.J., Tommelein, I.D., Ballard, G., and Zabelle, T.R. (1998). “WorkPlan Database for Work Package Production Scheduling.” Proc. 6th Annl. Conf. Intl. Group for Lean Construction, IGLC-6, 13-15 August, Guaruja, Brazil, 12 pp. Available at https://www.doczj.com/doc/1a15650011.html,/~tommelein/IGLC-6/ChooEtAl.pdf

Choo, H.J., Tommelein, I.D., Ballard, G., and Zabelle, T.R. (1999). "WorkPlan: Constraint-based Database for Work Package Scheduling." J. Constr. Engrg. and Mgmt., ASCE, 125 (3) 151-160. Available at https://www.doczj.com/doc/1a15650011.html,/~tommelein/papers/QCO000151.pdf

Chua, D.K.H., Jun, S.L., and Hwee, B.S. (1999). “Integrated Production Scheduler for Construction Look-ahead Planning.” Proc. 7th Ann. Conf. Intl. Group for Lean Constr., Univ. of Calif. Berkeley, CA, USA, 287-298. Available at https://www.doczj.com/doc/1a15650011.html,/~tommelein/IGLC-7/PDF/Chua&Jun&Hwee.pdf Fischer, M.A., Liston, K., and Kunz, J. (2000). “Requirements and Benefits of Interactive Workspaces in Construction.” Proc. 8th Intl. Conf. on Computing in Civil and Building Engrg., August, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA.

Hammond, J., Choo, H.J., Austin, S., Tommelein, I.D., and Ballard, G. (2000).

“Integrating Design Planning, Scheduling, and Control with DePlan.” Proc. 8th Annual Conf. Intl. Group for Lean Construction, IGLC-8, 26-28 July, Brighton, U.K., available at https://www.doczj.com/doc/1a15650011.html,/~tommelein/IGLC8-HammondEtAl.pdf

Jun, S.L, Chua, D.K.H, and Hwee, B.S. (2000). “Distributed Scheduling with Integrated Production Scheduler.” Proc. 8th Annual Conf. Intl. Group for Lean Construction, IGLC-8, 26-28 July, Brighton, U.K., available at https://www.doczj.com/doc/1a15650011.html,/spru/imichair/iglc8/13.pdf

Lean Construction Institute. (1999). Lookahead Planning: Streamlining the Work Flow that Supports the Last Planner, Workbook T5, Lean Construction Institute, https://www.doczj.com/doc/1a15650011.html,.

Microsoft Corporation (2000). Microsoft Project 2000, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, https://www.doczj.com/doc/1a15650011.html,/office/project/default.htm.

Tommelein, I.D. and Ballard, G. (1997). “Look-Ahead Planning: Screening and Pulling.”

2nd Intl. Seminar on Lean Constr., 20-21 October, organ. by A.S.I. Conte, Logical Systems, S?o Paulo, Brazil.

--- to do与doing的区另U 一般情况下,to do 是一般将来式,是打算去做什么(未做);doing是现在进行式,是现在正在做什么,或(此事已做过或已发生、正做) like to do 和like doing 的用法有什么区别 简单的记忆方法。当表示喜欢,用like doing ,如:He likes cooking in his house. She likes singing. 表示爱好。 当表示想要,欲做某事(但还没进行)用like to do ,例如:He likes to cook in his house.- 他想在自己家做饭吃。 She likes to stay with us.- 她想和我们带一块儿。(但还没进行) 2 forget doin g/to do forget to do 忘记要去做某事。(未做) forget doing 忘记做过某事。(已做) The light in the office is stil on. He forgot to turn it off. 办公室的灯还在亮着,它忘记关了。(没有做关灯的动作) He forgot turning the light off. 他忘记他已经关了灯了。(已做过关灯的动作) Don't forget to come tomorrow. 别忘了明天来。(to come动作未做) 3 remember doin g/to do remember to do 记得去做某事(未做) remember doing 记得做过某事(已做) Remember to go to the post office after school. 记着放学后去趟邮局。 Don't you remember see ing the man before? 你不记得以前见过那个人吗? 感官动词 see, watch, observe, notice, look at, hear, listen to, smell, taste, feel +doing表示动作的连续性,进行性 I saw him working in the garden yesterday. (强调”我见他正干活”这个动作) 昨天我见他正在花园里干活。

脐带间充质干细胞的研究进展 间充质干细胞(mesenchymal stem cells,MSC S )是来源于发育早期中胚层 的一类多能干细胞[1-5],MSC S 由于它的自我更新和多项分化潜能,而具有巨大的 治疗价值 ,日益受到关注。MSC S 有以下特点:(1)多向分化潜能,在适当的诱导条件下可分化为肌细胞[2]、成骨细胞[3、4]、脂肪细胞、神经细胞[9]、肝细胞[6]、心肌细胞[10]和表皮细胞[11, 12];(2)通过分泌可溶性因子和转分化促进创面愈合;(3) 免疫调控功能,骨髓源(bone marrow )MSC S 表达MHC-I类分子,不表达MHC-II 类分子,不表达CD80、CD86、CD40等协同刺激分子,体外抑制混合淋巴细胞反应,体内诱导免疫耐受[11, 15],在预防和治疗移植物抗宿主病、诱导器官移植免疫耐受等领域有较好的应用前景;(4)连续传代培养和冷冻保存后仍具有多向分化潜能,可作为理想的种子细胞用于组织工程和细胞替代治疗。1974年Friedenstein [16] 首先证明了骨髓中存在MSC S ,以后的研究证明MSC S 不仅存在于骨髓中,也存在 于其他一些组织与器官的间质中:如外周血[17],脐血[5],松质骨[1, 18],脂肪组织[1],滑膜[18]和脐带。在所有这些来源中,脐血(umbilical cord blood)和脐带(umbilical cord)是MSC S 最理想的来源,因为它们可以通过非侵入性手段容易获 得,并且病毒污染的风险低,还可冷冻保存后行自体移植。然而,脐血MSC的培养成功率不高[19, 23-24],Shetty 的研究认为只有6%,而脐带MSC的培养成功率可 达100%[25]。另外从脐血中分离MSC S ,就浪费了其中的造血干/祖细胞(hematopoietic stem cells/hematopoietic progenitor cells,HSCs/HPCs) [26, 27],因此,脐带MSC S (umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells, UC-MSC S )就成 为重要来源。 一.概述 人脐带约40 g, 它的长度约60–65 cm, 足月脐带的平均直径约1.5 cm[28, 29]。脐带被覆着鳞状上皮,叫脐带上皮,是单层或复层结构,这层上皮由羊膜延续过来[30, 31]。脐带的内部是两根动脉和一根静脉,血管之间是粘液样的结缔组织,叫做沃顿胶质,充当血管外膜的功能。脐带中无毛细血管和淋巴系统。沃顿胶质的网状系统是糖蛋白微纤维和胶原纤维。沃顿胶质中最多的葡萄糖胺聚糖是透明质酸,它是包绕在成纤维样细胞和胶原纤维周围的并维持脐带形状的水合凝胶,使脐带免受挤压。沃顿胶质的基质细胞是成纤维样细胞[32],这种中间丝蛋白表达于间充质来源的细胞如成纤维细胞的,而不表达于平滑肌细胞。共表达波形蛋白和索蛋白提示这些细胞本质上肌纤维母细胞。 脐带基质细胞也是一种具有多能干细胞特点的细胞,具有多项分化潜能,其 形态和生物学特点与骨髓源性MSC S 相似[5, 20, 21, 38, 46],但脐带MSC S 更原始,是介 于成体干细胞和胚胎干细胞之间的一种干细胞,表达Oct-4, Sox-2和Nanog等多

脐带血造血干细胞库管理办法(试行) 第一章总则 第一条为合理利用我国脐带血造血干细胞资源,促进脐带血造血干细胞移植高新技术的发展,确保脐带血 造血干细胞应用的安全性和有效性,特制定本管理办法。 第二条脐带血造血干细胞库是指以人体造血干细胞移植为目的,具有采集、处理、保存和提供造血干细胞 的能力,并具有相当研究实力的特殊血站。 任何单位和个人不得以营利为目的进行脐带血采供活动。 第三条本办法所指脐带血为与孕妇和新生儿血容量和血循环无关的,由新生儿脐带扎断后的远端所采集的 胎盘血。 第四条对脐带血造血干细胞库实行全国统一规划,统一布局,统一标准,统一规范和统一管理制度。 第二章设置审批 第五条国务院卫生行政部门根据我国人口分布、卫生资源、临床造血干细胞移植需要等实际情况,制订我 国脐带血造血干细胞库设置的总体布局和发展规划。 第六条脐带血造血干细胞库的设置必须经国务院卫生行政部门批准。 第七条国务院卫生行政部门成立由有关方面专家组成的脐带血造血干细胞库专家委员会(以下简称专家委

员会),负责对脐带血造血干细胞库设置的申请、验收和考评提出论证意见。专家委员会负责制订脐带血 造血干细胞库建设、操作、运行等技术标准。 第八条脐带血造血干细胞库设置的申请者除符合国家规划和布局要求,具备设置一般血站基本条件之外, 还需具备下列条件: (一)具有基本的血液学研究基础和造血干细胞研究能力; (二)具有符合储存不低于1 万份脐带血的高清洁度的空间和冷冻设备的设计规划; (三)具有血细胞生物学、HLA 配型、相关病原体检测、遗传学和冷冻生物学、专供脐带血处理等符合GMP、 GLP 标准的实验室、资料保存室; (四)具有流式细胞仪、程控冷冻仪、PCR 仪和细胞冷冻及相关检测及计算机网络管理等仪器设备; (五)具有独立开展实验血液学、免疫学、造血细胞培养、检测、HLA 配型、病原体检测、冷冻生物学、 管理、质量控制和监测、仪器操作、资料保管和共享等方面的技术、管理和服务人员; (六)具有安全可靠的脐带血来源保证; (七)具备多渠道筹集建设资金运转经费的能力。 第九条设置脐带血造血干细胞库应向所在地省级卫生行政部门提交设置可行性研究报告,内容包括:

加to do 的动词 attempt企图enable能 够 neglect忽视afford负担得 起 demand要求long渴 望 arrange安排destine注 定 mean意欲,打算begin开 始 expect期望omit忽略,漏 appear似乎,显得determine决定manage设 法cease停止 hate憎恨,厌恶pretend假装 ask问dread害 怕 need需要agree同 意

desire愿望love 爱 swear宣誓volunteer志愿 wish希望bear承 受 endeavor努力offer提 供 beg请求fail不 能 plan计划 bother扰乱;烦恼forget忘 记 prefer喜欢,宁愿care关心,喜欢happen碰 巧prepare准 备decide决 定learn学 习 regret抱歉,遗憾choose选择hesitate犹 豫profess表明

claim要求hope希 望 promise承诺,允许start开始undertake承 接want想要 consent同意,赞同intend想要refuse拒 绝decide决定 learn学习vow起contrive设法,图谋incline有…倾向propose提议seek 找,寻觅 try试图 2)下面的动词要求不定式做宾补:动词+宾语+动词不定式 ask要求,邀请get请,得 到 prompt促使allow允 许 forbid禁止prefer喜欢,宁愿announce宣 布force强

迫 press迫使bride 收 买 inspire鼓舞request请求 assist协助hate憎 恶 pronounce断定,表示advise 劝告exhort告诫,勉 励pray请求 authorize授权,委托help帮 助recommend劝告,推荐bear容 忍implore恳 求remind提醒 beg请求induce引 诱 report报告compel强 迫 invite吸引,邀请,summon传 唤command命 令intend想要,企

常见的“to do”与“doing”现象 有些动词后既可接to do,也可接doing,它们后接to do与doing在意思上有时有较大的差别。因为它们也是中考的常考点之一,因而我们应该搞清楚它们的区别。 1. stop to do/stop doing sth。 解析:stop to do sth.意为“停下来(正在做的事)去做(另外的)某事”,to do sth.在句中作目的状语。而stop doing sth.意为“停止做(正在做的)某事”。如Mary stopped to speak to me.玛丽停下(手头的工作)来跟我讲话。 When the teacher came in. the students stopped talking.老师进来时,学生们停止讲话。 2. remember to do/remember doing sth 解析:remember to do sth.意为“记住要去做某事”(还没有做)。而remember doing sth.意为“记得(已经)做过某事”如: Please remember to send the letter for me.请记住为我发这封信。 I don’t remember eating such food somewhere.我不记得在哪里吃过这种食物 3. forget to do/forget doing sth 解析:forget to do sth.意为“忘记做某事”(动作还没有发生)。而forget doing sth.意为“忘记做过某事”(动作已发生)。如: Don’t forget to bring your photo here.别忘了把你的相片带来。 I have forgotten giving the book to him.我忘记我已把书给了他。 4. go on to do/go on doing sth 解析:go on to do sth.意为“做完一件事,接着做另外一件事”,两件事之间有可能有某种联系。而go on doing sth.意为“继续做下去”。如: After reading the text, the students went on to do the exercises.学生们读完课文后,接着做练习。 It’s raining hard, but the farmers go on working on the farm.虽然天正下着大雨,但农民们继续在农场干活。 5. try to do/try doing sth 解析:try to do sth.意为“尽力去做某事”,而try doing sth.意为“(用某一种办法)试着去做某事”。如: Try to come a little early next time, please.下次请尽量早点来。 You can try working out the problem in another way.你可以试试用其它的方法解答这道题目。 6. can’t help to do/can’t help doing sth 解析:can’t help to do为动词不定式结构;can’t help doing sth.意为“身不由己地去做某事”或“情不自禁地去做某事。”如: We can’t help to finish it.我们不能帮忙完成此事。 I couldn’t help laughing when I saw her strange face.当我看到她奇怪的脸时,我情不自禁地笑了。 7. hear sb. do/hear sb. doing sth 解析:hear sb. do sth.意为“听见某人做某事”,指听到了这个动作的全过程;hear sb. doing sth.意为“听到某人做某事”,指听到时候,这个动作正在发生。如: I often hear him sing in the classroom.我经常听见他在教室里唱歌。 Do you hear someone knocking at the door?你听见有人在敲门吗? 应该说明的是:和hear的用法一样的还有see、watch、notice等。

To do 和 doing的用法 1. finish, enjoy, feel like, consider, imagine, keep, postpone, delay, mind, practise, suggest, risk, quit+doing 2. 1)forget to do 忘记要去做某事(此事未做) forget doing忘记做过某事(此事已做过或已发生) 2)stop to do 停止、中断(某件事),目的是去做另一件事 stop doing 停止正在或经常做的事 3)remember to do 记住去做某事(未做) remember doing记得做过某事(已做) 4) regret to do对要做的事遗憾 regret doing对做过的事遗憾、后悔 5)try to do努力、企图做某事 try doing试验、试一试某种办法 6) mean to do打算,有意要… mean doing意味着 7)go on to do 继而(去做另外一件事情) go on doing 继续(原先没有做完的事情) 8)propose to do 打算(要做某事) proposing doing建议(做某事) 9) like /love/hate/ prefer +to do 表示具体行为;+doing sth 表示抽象、倾向概念 (注)如果这些动词前有should一词,其后宾语只跟不定式,不能跟动名词。例如: I should like to see him tomorrow. 10) need, want, deserve +动名词表被动意义;+不定式被动态表示“要(修、清理等)”意思。 Don’t you remember seeing the man before你不记得以前见过那个人吗 You must remember to leave tomorrow.你可要记着是明天动身。 I don’t regret telling her what I thought.我不后悔给她讲过我的想法。(已讲过) I regret to have to do this, but I have no choice.我很遗憾必须这样去做,我实在没办法。(未做但要做) You must try to be more careful.你可要多加小心。 Let’s try doing the work some other way.让我们试一试用另外一种办法来做这工作。 I didn’t mean to hurt your feeling.我没想要伤害你的感情。 This illness will mean (your) going to hospital.得了这种病(你)就要进医院。 3.省to 的动词不定式 1)情态动词 ( 除ought 外,ought to): 2)使役动词 let, have, make: 3)感官动词 see, watch, look at, notice , observe, hear, listen to, smell, feel, find 等后作宾补,省略to。 注意:在被动语态中则to 不能省掉。 I saw him dance.

卫生部办公厅关于印发《脐带血造血干细胞治疗技术管理规 范(试行)》的通知 【法规类别】采供血机构和血液管理 【发文字号】卫办医政发[2009]189号 【失效依据】国家卫生计生委办公厅关于印发造血干细胞移植技术管理规范(2017年版)等15个“限制临床应用”医疗技术管理规范和质量控制指标的通知 【发布部门】卫生部(已撤销) 【发布日期】2009.11.13 【实施日期】2009.11.13 【时效性】失效 【效力级别】部门规范性文件 卫生部办公厅关于印发《脐带血造血干细胞治疗技术管理规范(试行)》的通知 (卫办医政发〔2009〕189号) 各省、自治区、直辖市卫生厅局,新疆生产建设兵团卫生局: 为贯彻落实《医疗技术临床应用管理办法》,做好脐带血造血干细胞治疗技术审核和临床应用管理,保障医疗质量和医疗安全,我部组织制定了《脐带血造血干细胞治疗技术管理规范(试行)》。现印发给你们,请遵照执行。 二〇〇九年十一月十三日

脐带血造血干细胞 治疗技术管理规范(试行) 为规范脐带血造血干细胞治疗技术的临床应用,保证医疗质量和医疗安全,制定本规范。本规范为技术审核机构对医疗机构申请临床应用脐带血造血干细胞治疗技术进行技术审核的依据,是医疗机构及其医师开展脐带血造血干细胞治疗技术的最低要求。 本治疗技术管理规范适用于脐带血造血干细胞移植技术。 一、医疗机构基本要求 (一)开展脐带血造血干细胞治疗技术的医疗机构应当与其功能、任务相适应,有合法脐带血造血干细胞来源。 (二)三级综合医院、血液病医院或儿童医院,具有卫生行政部门核准登记的血液内科或儿科专业诊疗科目。 1.三级综合医院血液内科开展成人脐带血造血干细胞治疗技术的,还应当具备以下条件: (1)近3年内独立开展脐带血造血干细胞和(或)同种异基因造血干细胞移植15例以上。 (2)有4张床位以上的百级层流病房,配备病人呼叫系统、心电监护仪、电动吸引器、供氧设施。 (3)开展儿童脐带血造血干细胞治疗技术的,还应至少有1名具有副主任医师以上专业技术职务任职资格的儿科医师。 2.三级综合医院儿科开展儿童脐带血造血干细胞治疗技术的,还应当具备以下条件:

The main barriers of communication are Noise,Distortion,Gender difference,Non-verbal communication,Problems in the message,Lack of communication skills,Information overload Noise refers to the interference or distraction that is in the environment in which the communication is taking place. Distortion refers to the loss of meaning of the message in handling. This largely occurs in the encoding and decoding stages of communication. Gender differences are a common barrier of communication. Men and women communicate for different reasons with different styles. Non-verbal communication is a very important barrier as oral communication is always accompanied by non-verbal cues that have a great tendency of encumbering the right message. As for problems in the message, the message could be incorrect, irrelevant, unsuitable, incomplete or difficult to understand or decipher. Also the encoder or decoder may lack communication skills, which becomes a barrier of communication. Lots of information that is also termed as information overload can also be a big hindrance in effective communication. The barriers are as follows: 1. Poor organization of ideas, awkward structure in adequate vocabulary, empty words and phrases in a confusing manner. 2. Message flows from higher level to lower level and back. In course of its flow it often passes through different levels of organization structure. This happens sue to carelessness on the part of those responsible for communicating it. 3. Even the most properly worded message may fail to serve its relevant and important, although it is not the case. Such act is known as assumption without clarification as specific reason. It is termed as unclarified assumptions. 4. Sometimes, a subordinate assures something believing that it is relevant and important, although it is not the case. Such act is known as assumption without clarification as specific reason. 5. Message involving some basic changes in person or other things must give time to the person for whom they are meant to adjust for the change. The transfer of information, ideas or attitude from one person to another. The person who is transferring information is source and the person who is

一.To do形式 afford to do sth. 负担得起做某事 agree to do sth. 同意做某事 arrange to do sth.安排做某事 ask to do sth. 要求做某事 beg to do sth. 请求做某事 care to do sth. 想要做某事 choose to do sth. 决定做某事 decide to do sth. 决定做某事 demand to do sth. 要求做某事 expect to do sth. 期待做某事 fear to do sth. 害怕做某事 help to do sth. 帮助做某事 hope to do sth. 希望做某事 learn to do sth. 学习做某事 manage to do sth. 设法做某事 offer to do sth. 主动提出做某事 plan to do sth. 计划做某事 prepare to do sth. 准备做某事 pretend to do sth. 假装做某事 promise to do sth. 答应做某事 refuse to do sth. 拒绝做某事 want to do sth. 想要做某事 wish to do sth. 希望做某事 happen to do sth. 碰巧做某事 struggle to do sth. 努力做某事 advise sb. to do sth. 建议某人做某事allow sb. to do sth. 允许某人做某事 ask sb. to do sth.请(叫)某人做某事bear sb. to do sth.忍受某人做某事 beg sb. to do sth. 请求某人做某事cause sb. to do sth. 导致某人做某事command sb. to do sth. 命令某人做某事drive sb. to do sth .驱使某人做某事elect sb. to do sth. 选举某人做某事encourage sb. to do sth. 鼓励某人做某事expect sb. to do sth. 期望某人做某事forbid sb. to do sth. 禁止某人做某事force sb. to do sth. 强迫某人做某事 get sb. to do sth. 使(要)某人做某事hate sb. to do sth. 讨厌某人做某事 help sb. to do sth. 帮助某人做某事

识记:初中英语非谓语动词总结(中考常考) 记住:动词后面加动名词表示已经做了;加动词不定式表示将要去做。 记住:动词后面加动名词表示经常做;加动词不定式表示一次做。 * *跟动词原形的词有:“一感二听三让四看”,即:feel, // hear, listen to, // let, make, have,// look at, see, wact notice.// 一.后面可跟动词的ing形式的情况。 1.动词:*以下记住每一个词组的第一个动词。 finish doing sth.完成做某事;enjoy doing sth. 喜欢做某事; practice doing sth. 练习做某事;imagine doing,想象做某事; avoid doing sth.避免做某事;consider doing sth.考虑做某事; suggest doing sth.建议做某事;mind doing sth.介意做某事; * keep doing sth.持续做某事, miss doing错过做, advise doing建议做;* keep sb doing让某人一直做 2.固定短语: feel like doing sth.喜欢做某事;be busy doing sth.忙于做某事; be worth doing 值得做某事;spend time (in) doing sth.花费时间(金钱)做某事; have difficult/trouble in doing sth做某事有困难;have fun doing.做某事高兴 3. 介词后(on, in, of, about, at, with, without, for, from, up, by等): 如:be good at doing sth.;thank you for doing sth.;give up doing sth.;stop sb. from doing sth.;do well in do sth.; be afraid of doing sth.;be interested in doing sth.;be proud of;instead of;be fond of;what/how about doing sth?某事怎么样? 4. to作介词时,后跟动名词的情况: look forward to doing sth期望做某事;prefer doing sth. to doing sth与…相比较更喜欢…; pay attention to doing注意做某事;be/get used to doing sth.习惯于做某事; make a contribution to doing为…做贡献 No+动名词,表示禁令No smoking禁止吸烟No parking禁止停车 5. go+动名词,意思是去进行某种活动或运动: go shopping,去购物;go skating,去滑冰;go hiking去远足(旅行) 6. do some/the+动名词,指进行某种活动: do some cleaning,搞卫生;do some washing 洗衣服; 二.后面可跟动词的不定式形式的情况。 1.动词:不需要记住哪些动词后跟动词不定式。 2.句型:(1)动词: allow sb. to do sth. 允许某人去做某事(区分allow doing sth) ask sb. (not) to do sth. 叫某人做事某事(叫某人不要去做某事) tell sb. (not) to do sth. 叫某人去(不要)做某事follow sb. to do sth. 跟随某人去做某事 get sb. to do sth. 让某人去做某事warn sb. (not) to do sth. 警告某人做某事(或不要做某事) encourage sb to do鼓励某人做、expect sb to do期待某人做 invite sb to do邀请某人做、teach sb to do教会某人做 advise sb to do建议某人做(区分advise / suggest doing sth) (2) Be+形容词adj.(即:情感类的形容词)+ to do

卫生部关于印发《脐带血造血干细胞库设置管理规范(试行)》的通知 发文机关:卫生部(已撤销) 发布日期: 2001.01.09 生效日期: 2001.02.01 时效性:现行有效 文号:卫医发(2001)10号 各省、自治区、直辖市卫生厅局: 为贯彻实施《脐带血造血干细胞库管理办法(试行)》,保证脐带血临床使用的安全、有效,我部制定了《脐带血造血干细胞库设计管理规范(试行)》。现印发给你们,请遵照执行。 附件:《脐带血造血干细胞库设置管理规范(试行)》 二○○一年一月九日 附件: 脐带血造血干细胞库设置管理规范(试行) 脐带血造血干细胞库的设置管理必须符合本规范的规定。 一、机构设置 (一)脐带血造血干细胞库(以下简称脐带血库)实行主任负责制。 (二)部门设置 脐带血库设置业务科室至少应涵盖以下功能:脐带血采运、处理、细胞培养、组织配型、微生物、深低温冻存及融化、脐带血档案资料及独立的质量管理部分。 二、人员要求

(一)脐带血库主任应具有医学高级职称。脐带血库可设副主任,应具有临床医学或生物学中、高级职称。 (二)各部门负责人员要求 1.负责脐带血采运的人员应具有医学中专以上学历,2年以上医护工作经验,经专业培训并考核合格者。 2.负责细胞培养、组织配型、微生物、深低温冻存及融化、质量保证的人员应具有医学或相关学科本科以上学历,4年以上专业工作经历,并具有丰富的相关专业技术经验和较高的业务指导水平。 3.负责档案资料的人员应具相关专业中专以上学历,具有计算机基础知识和一定的医学知识,熟悉脐带血库的生产全过程。 4.负责其它业务工作的人员应具有相关专业大学以上学历,熟悉相关业务,具有2年以上相关专业工作经验。 (三)各部门工作人员任职条件 1.脐带血采集人员为经过严格专业培训的护士或助产士职称以上卫生专业技术人员并经考核合格者。 2.脐带血处理技术人员为医学、生物学专业大专以上学历,经培训并考核合格者。 3.脐带血冻存技术人员为大专以上学历、经培训并考核合格者。 4.脐带血库实验室技术人员为相关专业大专以上学历,经培训并考核合格者。 三、建筑和设施 (一)脐带血库建筑选址应保证周围无污染源。 (二)脐带血库建筑设施应符合国家有关规定,总体结构与装修要符合抗震、消防、安全、合理、坚固的要求。 (三)脐带血库要布局合理,建筑面积应达到至少能够储存一万份脐带血的空间;并具有脐带血处理洁净室、深低温冻存室、组织配型室、细菌检测室、病毒检测室、造血干/祖细胞检测室、流式细胞仪室、档案资料室、收/发血室、消毒室等专业房。 (四)业务工作区域应与行政区域分开。

The given data is only intended as a product description and should not be regarded as a legal warranty of proper-ties or guarantee. In the interest of further technical developments, we reserve the right to make design changes. ACTIVE / ELECTRONICALL Y PROTECTED BARRIERS The following barriers have built-in overvolt protection, allowing their use with unregulated power supplies. In many applications, eg, sensor inputs or controller outputs, there is insufficient power available to blow the barrier fuse and this additional protection is not necessary. However, where the barrier is connected to a power supply, eg, for energising transmitters, switches, solenoids or local alarms, overvolt protection allows the barriers to be used with unregulated supplies and also gives protection against faulty wiring during commissioning. MTL7706+ for 'smart' 2-wire 4/20mA transmitters The MTL7706+ is a 1-channel shunt-diode safety barrier, with built-in electronic overvolt protection, for energising a 2-wire, 4/20mA transmitter in a hazardous area. It is powered from a positive supply of 20–35V dc and delivers a 4/20mA signal into an earthed load in the safe area. It is proof against short circuits in the field and in the safe area and is extremely accurate. The MTL7706+ will pass incoming communication signals up to 10kHz from a ‘smart’ transmitter, while in the outgoing direction it will pass signals of any frequency likely to be encountered. Since the MTL7706+ has no return channel for energising the load, the entire output of the single ‘28V’ channel is available to power the transmitter, providing high output capability. This channel is negatively polarised, and the safe-area signal is in fact the very current that returns through it from the hazardous area, the novel circuit being energised by a built-in floating dc supply derived from the external dc source of power. To prevent any leakage through the zener diodes and maximise the output voltage available at 20mA, the floating supply is given a rising voltage/current characteristic. A separate circuit limits the current to protect the fuse in the event of a short circuit in the hazardous area.With a 20V supply, the barrier will deliver 16.2V minimum at 20mA for the transmitter and lines and consumes typically 45mA at 24V operation. BASIC CIRCUIT ADDITIONAL SPECIFICATION Safety description 28V 300Ω 93mA Supply voltage 20 to 35V dc w.r.t earth Output current 4 to 20 mA Voltage available to transmitter and lines 16.2V @ 20mA with 250Ω load (negative w.r.t. earth)11.0V @ 20mA with 500Ω load (negative w.r.t. earth)Accuracy ±2μA under all conditions ACTIVE / ELECTRONICALLY PROTECTED BARRIERS Safe-area load resistance 0 to 500 ΩSupply current 45mA typical at 20mA and 24V supply 60mA maximum at 20mA and 20V supply MTL7707+ for switch inputs and switched outputs The MTL7707+ is a 2-channel shunt-diode safety barrier similar to the MTL7787+ but with built-in electronic overvolt protection. It is intended primarily for safeguarding a hazardous-area switch controlling a relay, opto-coupler or other safe-area load from an unregulated dc supply in the safe area. The outgoing channel accepts supply voltages up to +35V and is protected against reverse voltages: the return channel is unaffected by voltages up to +250V. In normal operation the protection circuit introduces only a small voltage drop and shunts less than 1mA to earth, so its overall effect is minimal. If the supply voltage exceeds about 27V, however, causing the Zener diodes to conduct – or if the safe-area load has a very low resistance – the supply current is limited automatically to 50mA, protecting the fuse and power supply and enabling the loop to continue working. BASIC CIRCUIT ADDITIONAL SPECIFICATION Safety description 28V 300Ω 93mA, terminals 1 to 328V Diode, terminals 2 -4Supply voltage 10 to 35V dc with respect to earth Output current Up to 35mA available Maximum voltage drop (at 20oC, current not limited) Iout x 345Ω + 0.3V, terminals 1 to 3Iout x 25Ω + 0.9V, terminals 4 to 2Supply current Iout + 1.6mA, supply <26V Limited to 50mA, supply >28V or low load resistance MTL7707P+ for switch inputs and switched outputs, 2W Transmitters (IIB gases) The MTL7707P+ is a two-channel shunt-diode safety barrier similar to the MTL7787P+, but is designed for use with group IIB gases and features built-in electronic overvolt protection allowing use with unregulated power supplies up to 35V dc. It is intended primarily as a low cost solution for driving IIB certified 2-wire 4/20mA transmitters, but can also be used with controller outputs with current monitoring, solenoid valves and switches. To protect the fuse and enable the loop to continue working, the supply current is limited automatically at 50mA should the output be short-circuited or excess voltage applied.