Anesthesia for removal of inhaled foreign bodies in children

AMIT SOODAN M D,DILIP PAWAR M D AND RAJESHWARI

SUBRAMANIUM M D

Department of Anaesthesiology,All India Institute of Medical Sciences,New Delhi,India

Summary

Background:Foreign body aspiration may be a life-threatening emer-

gency in children requiring immediate bronchoscopy under general

anesthesia.Both controlled and spontaneous ventilation techniques

have been used during anesthesia for bronchoscopic foreign body

removal.There is no prospective study in the literature comparing

these two techniques.This prospective randomized clinical trial was

undertaken to compare spontaneous and controlled ventilation during

anesthesia for removal of inhaled foreign bodies in children.

Methods:Thirty-six children posted for rigid bronchoscopy for

removal of airway foreign bodies over a period of2years and

2months in our institution were studied.After induction with sleep

dose of thiopentone or halothane,they were randomly allocated to one

of the two groups.In group I,17children were ventilated after

obtaining paralysis with suxamethonium.In group II,19children

were breathing halothane spontaneously in100%oxygen.

Results:All the patients in the spontaneous ventilation group had to

be converted to assisted ventilation because of either desaturation or

inadequate depth of anesthesia.There was a signi?cantly higher

incidence of coughing and bucking in the spontaneous ventilation

group compared with the controlled ventilation group(P?0.0012).

Conclusion:Use of controlled ventilation with muscle relaxants and

inhalation anesthesia provides an even and adequate depth of

anesthesia for rigid bronchoscopy.

Keywords:anesthesia;anesthetic technique:bronchoscopy;ventila-

tion;foreign body aspiration

Introduction

The aspiration of a foreign body in a child is a life threatening accident.Early diagnosis and broncho-scopic removal of the foreign body would protect the child from serious morbidity and even mortality. In infants and children,removal of airway foreign body is performed under general anesthesia and through a ventilating rigid bronchoscope.Anesthe-sia for rigid bronchoscopy is a challenging proce-dure for the anesthesiologist who must share the airway with the bronchoscopist and maintain ade-quate depth of anesthesia.It is often dif?cult to maintain adequate ventilation and oxygenation in these patients.During removal of foreign body in children,Fearson et al.(1),Chatterji et al.(2),Baraka (3),Kim et al.(4),Perrin et al.(5),and Ahmed(6)

Correspondence to:Dilip Pawar,Department of Anaesthesia,All

India Institute of Medical Sciences,New Delhi110029,India

(email:dkpawar@https://www.doczj.com/doc/0117292029.html,).

Pediatric Anesthesia200414:947–952doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2004.01309.x ó2004Blackwell Publishing Ltd947

maintained spontaneous respiration whereas Koslo-ske(7),Blazer et al.(8)and Puhakka et al.(9) controlled the ventilation.Although both sponta-neous and controlled ventilation techniques have been used successfully by these workers,there is no way of knowing the superiority of one technique over the other,as there is no study comparing the two techniques in the literature.This prospective randomized clinical trial was performed to compare these two techniques,namely controlled ventilation using muscle relaxant and spontaneous ventilation with inhalational anesthesia for rigid bronchoscopy for removal of airway foreign bodies.

Methods

This study was conducted at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences,New Delhi from October1998to November2000.After approval by our institutional ethics committee and obtaining informed consent of the parents,36consecutive children who presented for rigid bronchoscopy for suspected foreign body aspiration either as routine or emergency procedure were included in the study.

All the children were premedicated with atropine 0.01mg kg)1intravenously immediately prior to induction if intravenous access was present or otherwise after induction.Anesthesia was induced either by halothane inhalation by mask or by sleep dose of thiopentone.Vocal cords were sprayed with one puff(10mg)of lidocaine10%spray.After induction,the children were randomly allocated to one of the two groups,with the help of a computer generated random table.In group I the patient’s respiration was controlled where as group II patients were breathing spontaneously.In group I,introduc-tion of bronchoscope was facilitated by suxametho-nium 1.5mg kg)1whereas in group II it was performed under deep halothane.The children were maintained on intermittent positive pressure venti-lation(IPPV)with O2,halothane0.5%and intermit-tent doses of suxamethonium in group I and on spontaneous respiration with O2and halothane1.5–3%in group II.The fresh gas?ow varied from5to 10l?min)1and was titrated so as to allow adequate ?lling of the reservoir bag.The concentration of halothane delivered to the patient was titrated to the clinical parameters of adequate anesthesia.Depth of anesthesia was assessed clinically by hemodyanamic parameters(heart rate,blood pressure),lacrimation, sweating,pattern of respiration,movement,cough-ing and bucking and tone of abdominal recti muscles.The dial setting of the vaporizer and fresh gas?ows were recorded.

Anesthesia was maintained through a‘T’piece connected to the side arm of the rigid bronchoscope (Storz,Germany).Whenever there was persistent hypoxemia(saturation<90%for>2min)or inability to maintain adequate depth of anesthesia leading to dif?culty with bronchoscopy in a particular techni-que,it was decided to interrupt the technique and institute measures to restore normoxemia.In the spontaneous ventilation group,the respiration was assisted.In the controlled ventilation group the proximal end of bronchoscope was sealed and adequate ventilation ensured.

All children were monitored continuously for heart rate(HR),electrocardiography(ECG),pulse oximetry(SpO2),and endtidal carbon dioxide (P E CO2)and noninvasive blood pressure(NIBP)at 5min intervals.A20%change in the value of heart rate,systolic and diastolic blood pressures from the basal value was taken as a signi?cant change. Arterial desaturation was de?ned as SpO2value less than90%.The severity of desaturation was graded as mild(SpO2:80–90%;severity score1),moderate (SpO2:70–79%;severity score2),and severe (SpO2<70%;severity score3).Arterial blood gas (ABG)samples were taken immediately after induc-tion and at the end of the procedure.Signi?cant events(if any),duration of anesthesia and instru-mentation,and laryngeal evaluation by the broncho-scopist and anesthesiologist at end of the procedure were recorded.Lidocaine 1.5mg kg)1was given intravenously to all patients at the end of the procedure to decrease the incidence of coughing in the postbronchoscopy period.The children were taken to the recovery room from the operating room after they achieved a Steward’s recovery score(10)of ?ve or more.The children were nursed after the procedure with humidi?ed oxygen for2h.Postop-eratively,heart rate,respiratory rate,SpO2and episodes of coughing were monitored up to1h after the procedure or as long as such care was needed. Outcome variables studied in the present study were:(a)incidence of hypoxemia(duration and degree of episodes of desaturation),(b)depth of anesthesia judged clinically,(c)evidence of pushing

948 A.SOODAN ET AL.

ó2004Blackwell Publishing Ltd,Pediatric Anesthesia,14,947–952

the foreign body deeper into the respiratory tree during controlled ventilation.

The qualitative data such as sex,number of patients with intraoperative changes in heart rate and blood pressure,number of episodes of desatu-ration and incidence of complications in both groups were compared using chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate.The quantitative data such as age,weight,severity score of desaturation, ABG results and induction and recovery times were compared using the Students t-test after determining the normal distribution of the data.The values were

represented as mean±SD.The results were consid-ered signi?cant if P-value was less than0.05. Results

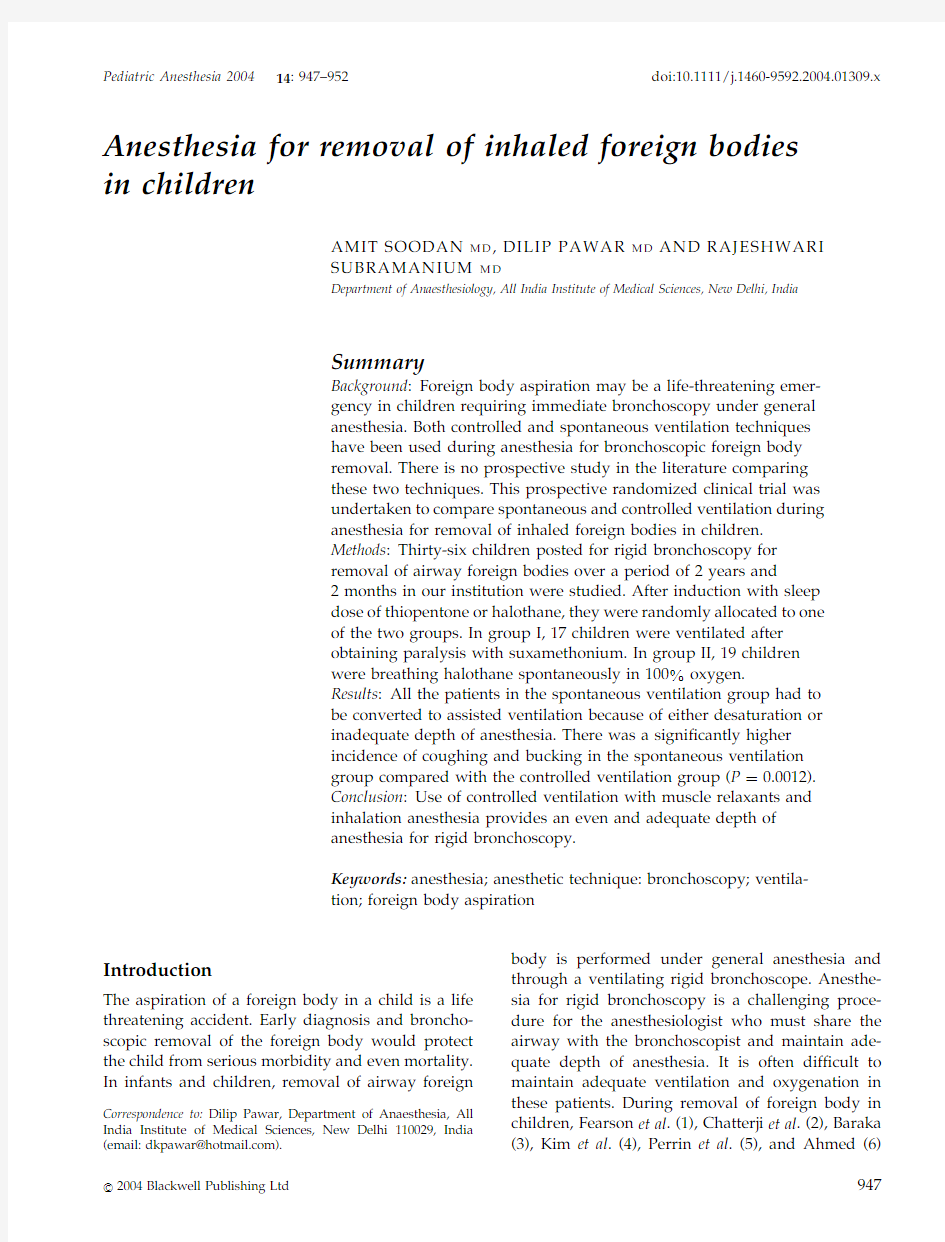

The age,weight and sex distribution in the two groups were comparable.The foreign bodies were mostly organic in nature with history of aspiration varying from1day to2months.The location of the foreign bodies was in either of the bronchi,or both the bronchi or bronchi as well as trachea(Table1). There was no statistically signi?cant difference in the number of patients with change in heart rate, systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure in the two groups.

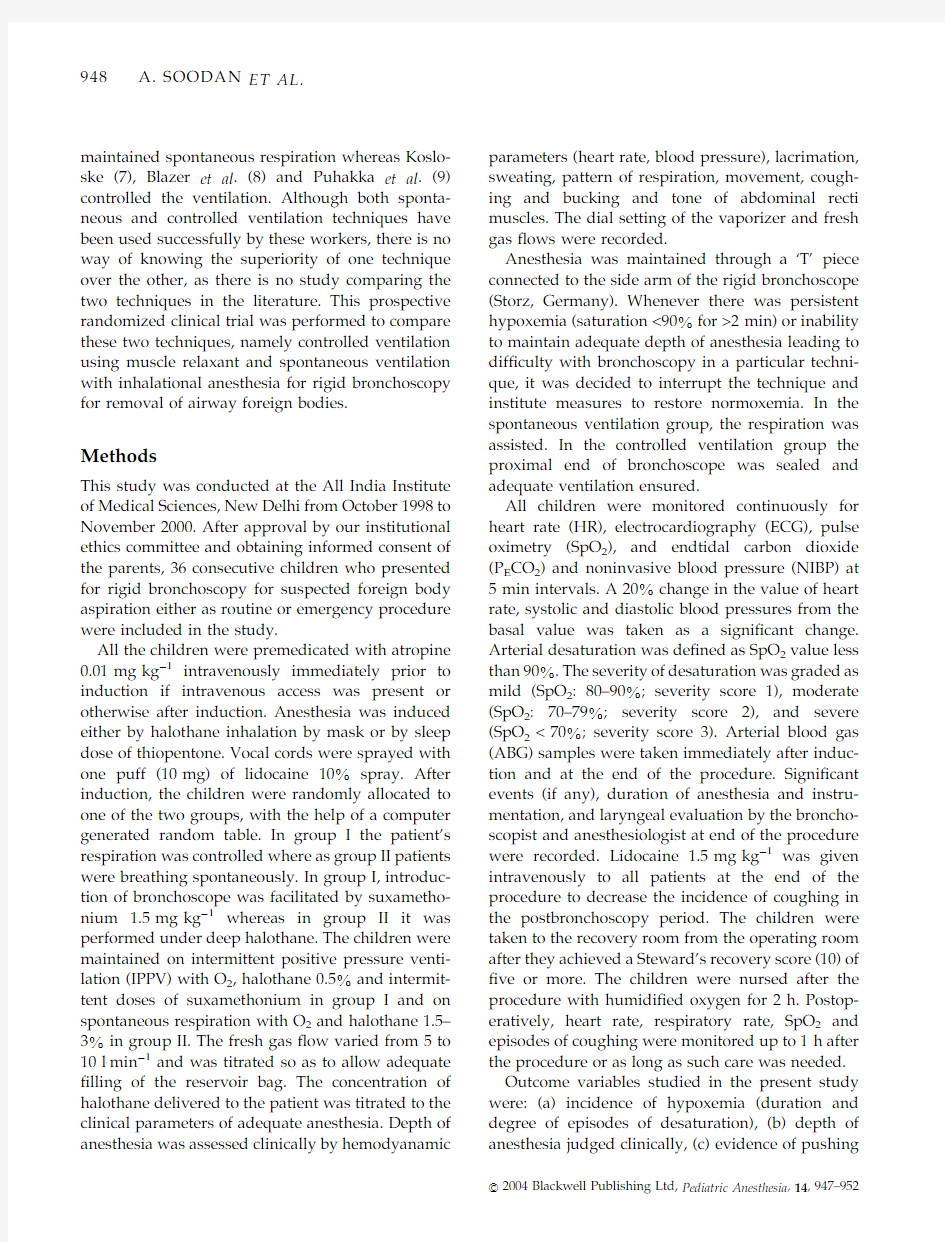

There were a total of26episodes of desaturation in17patients in group I and21episodes of desaturation in19patients in group II,giving a value of1.5and1.1episodes of desaturation per patient in groups I and II,respectively.The break down of the number of episodes of desaturation according to severity is given in Table2.The means of severity scores in groups I and II were1.5and1.1, respectively.The number of episodes of desatura-tion and the severity scores were comparable in both the groups.The episodes of desaturation in the spontaneous ventilation group were clinically asso-ciated with hypoventilation,breath holding or apnea whereas those in the controlled ventilation group were clinically associated with inability to ventilate because of gross leak at the proximal end and/or apnea when the surgeon was trying to remove or localize the foreign body in the airway.

All the patients breathing spontaneously had to be assisted to maintain adequate oxygen saturation. Two patients in the spontaneous ventilation group (group II)remained desaturated even after con-trolled ventilation throughout the procedure until the foreign body was removed from the airway.In these two patients,the respiration had to be assisted for a major duration of the procedure and later controlled.If we exclude these two patients from the spontaneous respiration group(group II),then the means of percentage time of procedure during which the patients remained desaturated in both groups were3.5±4.7%for group I and5.2±6.6%for group II.There was no statistically signi?cant difference. The complications seen in our study were intra-operative bucking and coughing,ventricular arrhythmia,laryngospasm,convulsion and post-operative laryngeal edema and severe cough (Table3).Incidence of intraoperative coughing and bucking in spontaneous group was statis-tically highly signi?cant(P?0.0012).All other complications were equally distributed between the two groups.There was no clinical evidence of pushing the foreign body deeper into the respiratory

Table1

Removed foreign bodies

Foreign body Number of patients Group I Group II Type

Organic271312 Inorganic514 Location

Right bronchus1679 Left bronchus853 Trachea413 Multiple sites419 Duration

<3Days1349

>3Days231310 Table showing the nature(organic or inorganic)and location of the foreign bodies removed and the duration of time for which these foreign bodies were in the respiratory tract in both groups.Table2

Severity of desaturation

Severity score Group I Group II 1(Mild)*1110

2(Moderate)**53

3(Severe)***108 Table showing the number of patients with mild,moderate and severe desaturations in each group.

*Severity score1(mild desaturation):SpO280–90%.

**Severity score2(moderate desaturation):SpO270–80%.

***Severity score3(severe desaturation):SpO2<70%.

INHALED FOREIGN BODIES IN CHILDREN949ó2004Blackwell Publishing Ltd,Pediatric Anesthesia,14,947–952

tree reported by any of the bronchoscopists in our study.The ABG results showed that there was mild hypercarbia and acidosis both at the start and the end of procedure in all the patients.The ABG results were comparable between the two groups.The continuous endtidal carbon dioxide data could not be obtained in all cases due to leakage of the expired gases around the bronchoscope.The time taken for induction of anesthesia was signi?cantly shorter in group I(4.4±4.0min)compared with group II(14.1±3.0min). Similarly,the recovery times were shorter in group I (9.1±4.7min)than in group II(22.4±8.6min).The differences in induction and recovery times were statistically signi?cant(P<0.001).

Discussion

The presence of foreign body in the respiratory tract is a serious and on occasion fatal condition requiring immediate intervention.For the removal of aspirated foreign bodies in children there is no substitute for a rigid ventilating bronchoscope.It provides a much higher quality image and larger channels for instru-mentation.During rigid bronchoscopy it is often dif?cult to maintain adequate ventilation and oxy-genation in these patients as pulmonary gas exchange is already deranged.It is dif?cult to maintain an adequate depth of anesthesia during the procedure,as there is a constant leak of anesthetic gases through the proximal end and around the bronchoscope. Ahmed(6)studied the records of58children who underwent rigid bronchoscopy for inhaled foreign bodies.General anesthesia was employed and spon-taneous respiration was maintained when possible. The author found that all children suffered from some respiratory embarrassment intraoperatively, although the report does not comment on the number of patients who had impaired oxygenation. Perrin et al.(5)found that they had to assist respiration in spontaneously breathing patients undergoing rigid bronchoscopy because of pro-longed apnea or oxygen desaturation.Baraka(3) used assisted ventilation in63children undergoing bronchoscopy for removal of inhaled foreign bodies. He assisted the ventilation by intermittent?ushing of oxygen via the sidearm of bronchoscope,without occluding the head of bronchoscope.In our study, we were unable to maintain any of the patients purely on spontaneous respiration and had to assist the respiration in all patients belonging to sponta-neous ventilation group.

Litman et al.(11)in a retrospective analysis of 18years’data showed that11of26cases of spon-taneous and5of18cases of assisted ventilation had to be changed to controlled ventilation.It is possible that spontaneous ventilation used at the outset was not suf?cient to maintain normoxia or paralysis was required because patients were moving.When there was a change in ventilatory technique it was always a change from spontaneous or assisted to controlled and not vice versa.In our study the respiration of all the patients in the spontaneous group had to be assisted and in two of them,later controlled. Kosloske(7),Blazer et al.(8)and Puhakka et al.(9) used controlled ventilation technique for removal of aspirated foreign bodies in children.They did not mention intraoperative problems because of positive pressure ventilation during bronchoscopy.In our study,in the controlled ventilation group patients, there was an even depth of anesthesia and there was no episode of the foreign body being dislodged or pushed distally during removal.It was possible to improve oxygenation by providing an effective seal. All the previously published reports are retro-spective data and have the inherent fault of incom-plete information of a retrospective analysis.This is the?rst prospective randomized study comparing spontaneous and controlled ventilation techniques. In our study the episodes of poor oxygenation and desaturation were because of bucking and coughing or from periods of shallow breathing,apnea or breath holding in the spontaneous respiration group. In the controlled ventilation group it was due to inadequate ventilation because of leakage of gas mixture from the proximal end of the bronchoscope or from prolonged apnea when the surgeon was

Table3

Complications

Complications Group I(n?17)Group II(n?19)

Intraop coughing and bucking112*

Ventricular arrhythmia13

Laryngospasm13

Convulsions01

Postop laryngeal edema54

Postop severe cough52

The number of patients with different complications in both

groups.*P?0.0012.

950 A.SOODAN ET AL.

ó2004Blackwell Publishing Ltd,Pediatric Anesthesia,14,947–952

attempting to localize or retrieve the foreign body from the airway.Assisting the respiration manually or sealing the proximal end of the bronchoscope improved oxygenation.The episodes of desaturation and their duration were comparable between the two groups after the respiration was assisted in group II.Had we not assisted the respiration,the duration of desaturation in these children would have been signi?cantly longer.Pawar has demon-strated in puppies that during spontaneous respir-ation,the minute ventilation decreases by50%and the lung compliance tends to be low(personal communication).This could be due to the increased resistance of the bronchoscope telescope system.The inadequate ventilation and inability to maintain oxygenation could be because of these changes in the pulmonary mechanics imposed by the introduc-tion of bronchoscope and telescope during sponta-neous breathing.During controlled ventilation,as the work of breathing is taken over by the anesthet-ist,the resistance is easily overcome and adequate volumes can be delivered.

Another cause of poor oxygenation could be inadequate depth of anesthesia,as evidenced by increased frequency of coughing and bucking.The leakage of anesthetic gases from the open end of the bronchoscope and around the bronchoscope com-bined with decreased ventilation leads to inadequate delivery of inhalational agent to maintain an even depth.

One of the reasons given by Woods et al.(12),Kim et al.(4),and Ahmed(6)for avoiding controlled ventilation during bronchoscopic removal of foreign bodies is the possible complication of forcing the foreign body further into the bronchial tree.Pawar (13)has given an account of four cases in which the foreign body was dislodged14times during removal in both spontaneous as well as controlled ventilation,but there was no incidence of the foreign body being pushed distally.In our study there was no incidence of the foreign body being pushed down the bronchial tree during removal in either of the groups.The risk of pushing down a foreign body by positive pressure ventilation seems to be overstated and unsubstantiated.

Attempts were made to maintain adequate depth of anesthesia in both groups.In the spontaneous venti-lation group,it was done by increasing the dial setting of delivered halothane from1.5to3%compared with 0.5%in the controlled ventilation group.There was even depth of anesthesia in the patients in the controlled ventilation group as evidenced by a lesser number of episodes of intraoperative coughing and bucking.This is because the patients were paralysed and constant positive pressure ventilation was provi-ded throughout the procedure delivering adequate anesthetic gases in oxygen to the lungs of the patient. Several complications are associated with rigid bronchoscopy such as coughing and bucking,pneu-mothorax,mediastinal and subcutaneous emphys-ema,laryngospasm,laryngeal edema,cardiac arrhythmia,cardiac arrest,convulsions and death (1–10,13).These could be due to many reasons such as inadequate depth of anesthesia,hypoxia,inad-equate ventilation and vagal stimulation.The com-plications reported by workers using controlled or spontaneous ventilation techniques are similar.In our study the complications in both the groups were comparable except for intraoperative coughing and bucking,which was worse in group II patients probably because of inadequate depth of anesthesia. In our study,the incidence of severe postoperative cough in the controlled ventilation group was higher although not statistically signi?cant,in spite of the same dose of intravenous lidocaine administered as in the spontaneous ventilation group probably because of early recovery and awakening.During rigid bronchoscopy the airway is manipulated repeatedly leading to airway edema and irritation. As a result,coughing is very common afterwards.It can be prevented by application of local anesthetic on the airway mucosa or by intravenous adminis-tration of lidocaine.Coughing could not have been because of pain in these patients as rigid bronchos-copy is not a painful procedure.

Convulsions under anesthesia are a serious and rare complication and can be due to factors such as hypoxia,hypercarbia or metabolic and electrolyte disturbances.In our study,one child in the sponta-neous respiration group had convulsions during bronchoscopy.This18-month-old girl was cyanosed, gasping and in respiratory distress on arrival.She had altered consciuosness with?accid limbs and low saturations(50%).She had severe hypercarbia [PaCO2:13kPa(100mmHg)]and mild acidosis(BE: )7.5).The convulsions were manifested in the lighter plane of anesthesia.The exact cause of convulsion in this patient cannot be ascribed to

INHALED FOREIGN BODIES IN CHILDREN951ó2004Blackwell Publishing Ltd,Pediatric Anesthesia,14,947–952

any particular factor as she had hypoxia,hypercar-bia,probable metabolic and electrolyte derange-ments.The lidocaine spray in to the cords might have contributed to the occurrence as its toxicity is manifested in the presence of metabolic disorders (14).It is very unlikely that the anesthetic technique contributed to the occurrence of seizures in this case. The number of patients required to identify signi?cant incidence of various complications in any technique is high.The number of patients studied and reported by different workers is small. That is why it is dif?cult to make de?nite remarks on the contribution of any particular technique to the incidence of complications.However,most of the complications of bronchoscopy reported are due to inadequate depth of anesthesia.In spontaneously breathing patients,the depth of anesthesia has been shown to be inadequate and uneven compared with those on controlled ventilation.

From this study,we conclude that it is not possible to maintain an adequate depth of anesthesia with spontaneous respiration during rigid bronch-oscopy for removal of inhaled foreign body in children and that respiration needs to be assisted. The use of controlled ventilation with muscle relax-ants and inhalational anesthesia provides an even and adequate depth of anesthesia for rigid bronch-oscopy.Considering the considerable morbidity and mortality associated with these procedures,they should not be taken lightly.We recommend routine use of controlled ventilation for bronchoscopy for the removal of inhaled foreign bodies.References

1Fearson B.Anesthesia in pediatric per oral endoscopy.Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol1969;78:470–475.

2Chatterji S,Chatterji P.The management of foreign bodies in air passages.Anaesthesia1972;27:390–395.

3Baraka A.Bronchoscopic removal of inhaled foreign bodies in children.Br J Anaesth1974;46:124–126.

4Kim G,Brummitt WM,Humphry A et al.Foreign body in the airway:a review https://www.doczj.com/doc/0117292029.html,ryngoscope1973;83:347–354. 5Perrin G,Colt HG,Martin C et al.Safety of interventional rigid bronchoscopy using intravenous anesthesia and spontaneous assisted ventilation.A prospective study.Chest1992;102: 1526–1530.

6Ahmed AA.Bronchoscopic extraction of aspirated foreign bodies in children in Harare.East Afr Med J1996;73:244–246. 7Kosloske AN.Bronchoscopic extraction of aspirated foreign bodies in children.Am J Dis Child1982;136:924–927.

8Blazer S,Naveh Y,Friedman A.Foreign body in the airway.

Am J Dis Child1980;134:68–71.

9Puhakka H,Kero P,Valli P et al.Pediatric bronchoscopy.A report of methodology and results.Clin Pediatr1989;28:253–257.

10Steward DJ.A simpli?ed scoring system for the postoperative recovery room.Can Anaesth Soc J1975;22:111–113.

11Litman RS,Ponnuri J,Trogan I.Anesthesia for tracheal or bronchial foreign body removal in children:an analysis of ninety-four cases.Anesth Analg2000;91:1389–1391.

12Woods AM.Pediatric endoscopy.In:Berry FA,ed.Anesthetic Management of Dif?cult and Routine Pediatric Patients,2nd edn.

New York:Churchill Livingstone,1990:199–242.

13Pawar DK.Dislodgement of bronchial foreign body during retrieval in children.Paediatr Anaesth2000;10:333–335.

14Englesson S,Matousek M.Central nervous system effects of local anaesthetic agents.Br J Anaesth1975;47(Suppl.): 241–246.

Accepted3December2003

952 A.SOODAN ET AL.

ó2004Blackwell Publishing Ltd,Pediatric Anesthesia,14,947–952

小儿气道异物取出术的麻醉经验总结(1) 【摘要】气道内异物尤其是小儿气道内异物吸入是一种危及生命的急重症,抢救首选方法至今仍是在硬支气管镜下行气道异物取出。手术在狭窄的气道内进行,因与硬支气管镜与通气共用一个通道,在保证患儿接受安全无痛苦的手术同时,提供手术医师良好的气道视野,是该类手术麻醉的关键和难点。术中可以利用硬支气管镜对病儿供氧或进行控制或辅助呼吸以缓解低氧血症。 【关键词】小儿气道异物麻醉 【Abstract】 Airway foreign bodies, especially pediatric airway foreign body aspiration is a severe life-threatening emergency, rescue the preferred method is still OK in hard bronchoscopic removal of airway foreign body. Surgery carried out in a narrow airway, and ventilation for rigid bronchoscopy to share a channel, in ensuring the safety of children received no painful surgery at the same time, provide a good surgeon airway vision, it is the key to such anesthesia. Intraoperative rigid bronchoscopy can be used for sick children or to control or oxygen-assisted breathing to relieve hypoxemia

小儿麻醉的气道管理 一. 小儿呼吸道的解剖生理学特点 1. 鼻孔小,是6个月内的主要呼吸通道; 2. 舌相对大,喉相对小,位置高; 3. 会厌短,常呈Ω形或U形; 4. 环状软骨是小儿喉的最狭窄处; 5. 3个月以下婴儿的气管短,平均长度仅5.7cm; 6. 小儿扁桃体和腺样体在4~6岁时达最大形状; 7. 头大,颈短; 8. 氧耗增加和氧储蓄低; 9. 面罩通气容易胃扩张,易反流误吸、FRC、肺顺应性易下降; 10.心动过缓是对缺氧的主要反应,心率是心排出量的主要决定因素;随着麻醉的加深,维持上呼吸道开放的肌肉逐渐松弛,咽气道易塌陷,导致上呼吸道梗阻; 11.小儿呼吸道开放活动的调节。 二. 面罩通气 1. 选择适合于小儿面部形状、死腔量最小的面罩 透明面罩:最常用,小儿不易惊恐,可观察患儿口鼻部情况; Rendell-Baker面罩:形状符合小儿的面部轮廓,无效腔量较小,但没有充气密闭圈; Laerdal面罩:质地柔软的硅橡胶面罩,密闭性较好,能进行煮沸和高压蒸气消毒。 2. 面罩通气的操作要点: ①正确放置面罩: ②手法: 3. 面罩通气时的监测 —监测呼吸音或呼吸运动 —监测P ET CO2波形 —监测呼吸囊的运动 4. 口咽通气道的使用: —小儿常选用Guedel和Berman口咽通气道。 注意点: 在插入口咽通气道前应达满意的麻醉深度;

选择合适的口咽通气道,长度大约相当于从门齿至下颌角的长度。 三. 气管内插管 1. 插管前器械和物品准备 气管插管基本器械的准备 预氧和通气器械 1. 麻醉机或通气装置的准备 2. 准备小、中、大号面罩 3. 准备小、中、大号口咽和鼻咽通气道 气管导管及相关物品 4. 准备小、中、大三根经口插入的气管导管 5. 准备柔韧的插管芯(大小各一) 6. 准备润滑剂(最好含局麻药) 7. 喷雾器(含局麻药) 8. 准备注气注射器 喉镜操作相关设备 9. 打开吸引器,并连续硬质 10. 插管钳 11. 光源正常的1#、2#、3#Miller喉镜片,新生儿应准备直喉镜片 12. 置病人头部呈“嗅物位”的枕头或薄垫 固定气管导管所需的物品 13. 胶布(布质或丝质为好,不用纸质)或固定带 14. 牙垫(大、小) 确定气管导管位置所需的器械 15. 听诊器 16. P ET CO2监测仪 17. 脉搏氧饱和度仪 2. 喉镜检查 ①保持头的正确位置:6岁以下小儿头置于水平位,以头圈固定,由于这种年龄组小儿喉头位置高,如有必要可在环状软骨上加压,以更好地暴露声门。 6岁以上小儿,头置于小枕头上轻度屈曲颈椎,可改善插管角度和更好地显示声门。 ②仔细检查牙齿:因许多儿童开始更换乳牙,在喉镜检查必须注意,在插管时用大拇指推开嘴唇,对牙齿不施加任何压力。术前如发现有明显松动的牙齿,需向其家长说明拔掉松动牙齿能保证小孩在麻醉中的安全,拔出的牙齿在术后归还给家长。 ③在婴幼儿和儿童

气道异物取出术麻醉专家共识(2017) ??左云霞,冯春,刘金柱,李天佐(负责人/共同执笔人),李文献(共同执笔人),李丽伟,李梅,连庆泉,吴震(共同执笔人),张旭,张诗海,张溪英,金立民,胡智勇,蔡一榕,裴凌 ??一、定义 ?? 异物( ②声门上(异物 。 ??? [1-4]。 ??? ???临床上的“气道异物”一般多指狭义的气道异物。气道异物多见于3岁以下的婴幼儿,所占比例约为70%~80%,男孩发病率高于女孩,农村儿童发病率高于城市儿童[1-4]。80%以上的气道异物位于一侧支气管内,少数位于声门下及主气道内,极少数患儿异物位于多个部位。右侧支气管异物多于左侧[1,3,4],但也有文献报道左右两侧支气管异物的发生率相似[5]。气道异物是导致4岁以下儿童意外死亡的主要

原因,国内报道的入院后死亡率在0.2%~1%[4,6],美国报道的入院后死亡率为3.4%[7]。 ???三、病理生理学 ???异物吸入气道造成的损伤可分为直接损伤和间接损伤。直接损伤又包括机械损伤(如黏膜损伤、出血等)和机械阻塞。异物吸入后可能嵌顿在肺的各级支气管,造 应[8];止回阀;球阀 )。间接损伤 ??? ???1. ??? ???2.影像学检查 ???胸透、胸片、颈侧位片、CT等影像学检查可以协助诊断。一般认为,胸透见呼吸时纵膈摆动具有较大的诊断意义[2]。约25%的患儿胸片显示正常,只有约10%的异物能在X线照射下显影,大多数情况下胸片显示的是一些提示气道异物的间接征象,如肺气肿、肺不张、肺渗出等[1,2,10]。胸片结合胸透检查可以提高早期诊断率。

颈侧位片有助于发现声门下气道异物。CT三维重建技术可以准确地识别异物,检查结果与传统硬支气管镜检查结果的符合率较高,可以作为诊断气道异物的一个选择[11-13]。 ???3.其他 ???纤维支气管镜检查(fiberopticbronchoscopy)是一种微创的诊断方法,对可疑患 ??? 但仅有 查。 ??? ???大小、性质、存留时间以及并发症不同,可导致病情进展各异。 ???1.异物进入期 ???异物经过声门进入气管时,均有憋气和剧烈咳嗽。若异物嵌顿于声门,可发生极度呼吸困难,甚至窒息死亡;若异物进入更深的支气管内,除有轻微咳嗽或憋气以外,可没有明显的临床症状。

气道异物取出术麻醉专家共识(2017) 左云霞,春,金柱,天佐(负责人/共同执笔人),文献(共同执笔人),丽伟,梅,连庆泉,吴震(共同执笔人),旭,诗海,溪英,金立民,胡智勇,蔡一榕,裴凌 一、定义 所有自口或鼻开始至声门及声门以下呼吸径路上的异物存留,都可以称之为气道异物(airway foreign body)。异物位置对于麻醉管理具有重要意义,本共识将气道异物按其所处的解剖位置分为以下四类:①鼻腔异物(nasal foreign body);②声门上(声门周围)异物(supraglottic foreign body) ;③声门下及气管异物(subglottic and tracheal foreign body);④支气管异物(bronchial foreign body)。狭义的气道异物是指位于声门下、气管和支气管的异物。 此外,按照化学性质可将气道异物分为有机类和无机类异物。有机类异物以花生、葵花籽、西瓜子等植物种子多见,无机类异物则常见玩具配件、纽扣、笔套等[1-4]。按异物来源可分为源性和外源性异物,患者自身来源或接受手术时产生的血液、脓液、呕吐物及干痂等为源性异物,而由口鼻误入的外界异物为外源性异物。医源性异物是指在医院实施诊断、手术、治疗等技术操作时造成的气道异物,常见的有患者脱落的牙齿、医用耗材和医疗器械配件等。

二、流行病学 临床上的“气道异物”一般多指狭义的气道异物。气道异物多见于3岁以下的婴幼儿,所占比例约为70%~80%,男孩发病率高于女孩,农村儿童发病率高于城市儿童[1-4]。80%以上的气道异物位于一侧支气管,少数位于声门下及主气道,极少数患儿异物位于多个部位。右侧支气管异物多于左侧[1,3,4],但也有文献报道左右两侧支气管异物的发生率相似[5]。气道异物是导致4岁以下儿童意外死亡的主要原因,国报道的入院后死亡率在0. 2%~1%[4,6],美国报道的入院后死亡率为3.4%[7]。 三、病理生理学 异物吸入气道造成的损伤可分为直接损伤和间接损伤。直接损伤又包括机械损伤(如黏膜损伤、出血等)和机械阻塞。异物吸入后可能嵌顿在肺的各级支气管,造成阻塞部位以下的肺叶或肺段发生肺不或肺气肿。异物存留会导致不同的阀门效应[8],如双向阀(bypass valve)效应,指气流可进可出但部分受限(图1A);止回阀(check valve)效应,指气流进入多于流出,导致阻塞性肺气肿(图1B);球阀(ball valve)效应,气流能进入但不能流出,导致阻塞性肺气肿(图1C);截止阀(stop valve)效应,指气流无法进出,肺气体吸收导致阻塞性肺不(图1D)。间接损伤是指存留的异物导致炎症反应、感染或肉芽形成等。 四、诊断 1. 病史、症状和体征

小儿麻醉气道和呼吸管理指南(2014) 上官王宁(共同执笔人)王英伟左云霞李师阳连庆泉(共同执笔人/负责人)姜丽华张建敏 一、目的 在已报道的与麻醉相关的并发症中,新生儿和婴幼儿、急诊手术以及合并呼吸问题(气道梗阻、意外拔管、困难插管)等仍是高危因素。气道和呼吸管理仍是小儿麻醉主要出现并发症和死亡的主要因素。小儿麻醉科医师必须了解与熟悉小儿的解剖生理特点,并根据不同年龄选用合适的器械设备,采取相应的管理措施,才能确保患儿手术麻醉的安全。 二、小儿气道解剖特点 1. 头、颈婴幼儿头大颈短,颈部肌肉发育不全,易发生上呼吸道梗阻,即使施行椎管内麻醉,若体位不当也可引发呼吸道阻塞。 2. 鼻鼻孔较狭窄,是6个月内小儿的主要呼吸通道,分泌物、粘膜水肿、血液或者不适宜的面罩易导致鼻道阻塞,出现上呼吸道梗阻。 3. 舌、咽口小舌大,咽部相对狭小及垂直,易患增殖体肥大和扁桃体炎。 4. 喉新生儿、婴儿喉头位置较高,声门位于颈3~4平面,气管插管时可压喉头以便暴露喉部。婴儿会厌长而硬,

呈“U”型,且向前移位,挡住视线,造成声门显露困难,通常用直喉镜片将会厌挑起易暴露声门。由于小儿喉腔狭小呈漏斗形(最狭窄的部位在环状软骨水平,即声门下区),软骨柔软,声带及粘膜柔嫩,易发生喉水肿。当气管导管通过声门遇有阻力时,不能过度用力,而应改用细一号导管,以免损伤气管,导致气道狭窄。 5. 气管新生儿总气管长度约4~5cm,内径4~5mm,气管长度随身高增加而增长。气管分叉位置较高,新生儿位于3~4胸椎(成人在第5胸椎下缘)。3岁以下小儿双侧主支气管与气管的成角基本相等,与成人相比,行气管内插管导管插入过深或异物进入时,进入左或右侧主支气管的几率接近。 6. 肺小儿肺组织发育尚未完善,新生儿肺泡数只相当于成人的8%,单位体重的肺泡表面积为成人的1/3,但其代谢率约为成人的两倍,因此新生儿呼吸储备有限。肺间质发育良好,血管组织丰富,毛细血管与淋巴组织间隙较成人为宽,造成含气量少而含血多,故易于感染,炎症也易蔓延,易引起间质性炎症、肺不张及肺炎。由于弹力组织发育较差,肺膨胀不够充分,易发生肺不张和肺气肿;早产儿由于肺发育不成熟,肺表面活性物质产生或释放不足,可引起广泛的肺泡萎陷和肺顺应性降低。

气道异物取出术麻醉专家共识(全文) 一、定义 广义上讲,所有自口或鼻开始至声门及声门以下所有呼吸径路上的异物存留都可以称之为气道异物(airway foreign body)。由于异物位置对于麻醉管理具有重要意义,本共识将气道异物按照异物所处的解剖位置分为以下四类:①鼻腔异物(nasal foreign body);②声门上(声门周围)异物(supraglottic foreign body);③声门下及气管异物 (subglottic and trachea foreign body);④支气管异物 (bronchial foreign body)。狭义的气道异物定义是指位于声门下及气管和支气管的异物。 气道异物还可有多种分类方法。按异物来源可分为内源性和外源性异物,血液、脓液、呕吐物及干痂等为内源性异物;而由口鼻误入的一切异物属外源性异物。按照异物的物理性质可以分为固体和非固体异物,常见的是固体异物。按照异物的化学性质又可分为有机类和无机类异物,有机类异物多于无机类异物,有机类异物中又以花生、西瓜子、葵花籽等植物种子最为多见;无机类异物中则常见玩具配件、纽扣、笔套等。 二、流行病学 文献报道中所指的“气道异物”多指狭义的气道异物,即声门下、气管和支气管的异物。气道异物多见于3岁以内的婴幼儿,所占比例约为70~80%,4~7岁的学龄前儿童约占20%。男孩发病率高于女孩。80%以上

的气道异物位于一侧支气管内,少数位于声门下及总气道内,在极少数患儿异物位于多个部位;多数回顾性调查发现右侧支气管异物多于左侧,也有文献报道左右两侧发生率相似。气道异物是导致4岁以内儿童意外死亡的主要原因。在美国,每年约有500~2000个儿童因气道异物死亡,入院后死亡率为3.4%,国内报道的入院后死亡率在0.2~1%,尚缺乏入院前死亡率的资料。 三、病理生理学 异物吸入气道造成的损伤可分为直接损伤和间接损伤。直接损伤又包括机械损伤(如粘膜损伤、出血等)和机械阻塞。异物吸入后可能嵌顿在肺的各级支气管,造成阻塞部位以下的肺叶或肺段发生肺不张、肺气肿的改变。异物存留会导致不同的阀门效应,如双向阀(bypass valve)效应,指气流可进可出但部分受限(图1A);止回阀(check valve)效应,指气流进入多于流出,导致阻塞性肺气肿(图1B);球阀(ball valve)效应,气流能进入但不能流出,导致阻塞性肺气肿(图1C);截止阀(stop valve)效应,指气流无法进出,肺内气体吸收导致阻塞性肺不张,(图1D)。间接损伤是指存留的异物导致炎症反应、感染、肉芽形成等。

小儿麻醉的气道管理 温州医学院附二院连庆泉 一. 小儿呼吸道的解剖生理学特点 1. 鼻孔小,是6个月内的主要呼吸通道; 2. 舌相对大,喉相对小,位置高; 3. 会厌短,常呈Ω形或U形; 4. 环状软骨是小儿喉的最狭窄处; 5. 3个月以下婴儿的气管短,平均长度仅5.7cm; 6. 小儿扁桃体和腺样体在4~6岁时达最大形状; 7. 头大,颈短; 8. 氧耗增加和氧储蓄低; 9. 面罩通气容易胃扩张,易反流误吸、FRC、肺顺应性易下降; 10.心动过缓是对缺氧的主要反应,心率是心排出量的主要决定因素;随着麻醉的加深,维持上呼吸道开放的肌肉逐渐松弛,咽气道易塌陷,导致上呼吸道梗阻; 11.小儿呼吸道开放活动的调节。 二. 面罩通气 1. 选择适合于小儿面部形状、死腔量最小的面罩 透明面罩:最常用,小儿不易惊恐,可观察患儿口鼻部情况; Rendell-Baker面罩:形状符合小儿的面部轮廓,无效腔量较小,但没有充气密闭圈;

Laerdal面罩:质地柔软的硅橡胶面罩,密闭性较好,能进行煮沸和高压蒸气消毒。 2. 面罩通气的操作要点: ①正确放置面罩: ②手法: 3. 面罩通气时的监测 —监测呼吸音或呼吸运动 —监测P ET CO2波形 —监测呼吸囊的运动 4. 口咽通气道的使用: —小儿常选用Guedel和Berman口咽通气道。

注意点: 在插入口咽通气道前应达满意的麻醉深度; 选择合适的口咽通气道,长度大约相当于从门齿至下颌角的长度。 三. 气管内插管 1. 插管前器械和物品准备 气管插管基本器械的准备 预氧和通气器械 1. 麻醉机或通气装置的准备 2. 准备小、中、大号面罩 3. 准备小、中、大号口咽和鼻咽通气道 气管导管及相关物品 4. 准备小、中、大三根经口插入的气管导管 5. 准备柔韧的插管芯(大小各一) 6. 准备润滑剂(最好含局麻药) 7. 喷雾器(含局麻药) 8. 准备注气注射器 喉镜操作相关设备 9. 打开吸引器,并连续硬质 10. 插管钳 11. 光源正常的1#、2#、3#Miller喉镜片,新生儿应准备直喉镜片 12. 置病人头部呈“嗅物位”的枕头或薄垫 固定气管导管所需的物品 13. 胶布(布质或丝质为好,不用纸质)或固定带 14. 牙垫(大、小) 确定气管导管位置所需的器械 15. 听诊器 16. P ET CO2监测仪 17. 脉搏氧饱和度仪 2. 喉镜检查 ①保持头的正确位置:6岁以下小儿头置于水平位,以头圈固定,由于这种年龄组小儿喉头位置高,如有必要可在环状软骨上加压,以更好地暴露声门。 6岁以上小儿,头置于小枕头上轻度屈曲颈椎,可改善插管角度和更好地显示声门。 ②仔细检查牙齿:因许多儿童开始更换乳牙,在喉镜检查必须注意,在插管时用大拇指推开嘴唇,对牙齿不施加任何压力。术前如发现有明显松动的牙齿,需向其家长说明拔掉

纤维支气管镜下小儿气管异物取出术的 麻醉处理 (作者:___________单位: ___________邮编: ___________) 【摘要】为探讨纤维支气管镜下小儿气管异物取出术的麻醉处理方法,选择34例气管异物小儿均在肌注氯胺酮2~3mg/kg基础麻醉后入室,静注地塞米松0.3~0.5mg/kg、1%利多卡因1mg/kg、丙泊酚1.5~2.5mg/kg、芬太尼1~2μg/kg诱导,麻醉维持以丙泊酚5~8mg/(kg·h)泵注。结果,麻醉前后患儿HR、MAP、SPO2变化无明显差异。有5例出现一过性呼吸抑制,2例呛咳,经静脉推注地塞米松、丙泊酚后缓解。所有患儿均在20min内清醒。利多卡因、芬太尼、丙泊酚配伍全静脉麻醉用于小儿气管异物取出术是一种比较安全且苏醒快的麻醉方法。 【关键词】儿童气管异物麻醉 小儿气管内异物取出术麻醉的主要困难在于麻醉与手术共用同一呼吸道,有相互干扰问题,手术风险性增大。因该类手术的时间不确定,对麻醉的要求高。手术期间要求维持足够的肺泡气体交换和适当的麻醉深度,减轻应激反应,术毕苏醒快、呼吸通畅。本文就纤维支气管镜下小儿气管异物取出的麻醉处理方式探讨如下。

1 资料与方法 1.1 一般资料 小儿气管异物34例,年龄1.5~6岁。男28例,女6例。体重12~25kg,ASAⅠ~Ⅱ级。 1.2 麻醉方法及用药 术前30min肌注阿托品0.02mg/kg,苯巴比妥钠2mg/kg(婴幼儿不用)。入室前肌注氯胺酮2~3mg/kg。入室后开放静脉推注地塞米松0.3~0.5mg/kg,1%利多卡因1mg/kg,丙泊酚1.5~2.5mg/kg(商品名:静安,费森尤斯-卡比公司生产),芬太尼1~2μg/kg诱导,用微量泵以5~8mg/(kg·h)泵入丙泊酚。以喉镜挑起会厌,明视下于咽喉部、声门及声门下喷2%利多卡因充分表面麻醉或经环甲膜穿刺气管内注射局麻药,面罩给氧约5min后开始手术,将高频喷射呼吸机接于纤维支气管镜上。通气频率60bpm,驱动压0.3~0.5kg/cm2,吸呼比1∶1.5~2。异物取出后停药。 1.3 观察指标 记录诱导前、置镜前、置镜后5min、术毕后5min的心率(HR)、平均动脉压(MAP)、脉搏氧饱和度(SPO2)。监测呼吸抑制、呛咳、呃逆等不良反应。 1.4 统计学方法 所有数据等用均数±标准差(±s)表示。P<0.05有统计学意义。 2 结果 34例患儿均能顺利置入纤维支气管镜。其中有5例出现一过性呼吸

小儿麻醉的气道管理 温州医学院附二院 连庆泉 一. 小儿呼吸道的解剖生理学特点 1. 鼻孔小,是6个月内的主要呼吸通道; 2. 舌相对大,喉相对小,位置高; 3. 会厌短,常呈Ω形或U 形; 4. 环状软骨是小儿喉的最狭窄处; 5. 3个月以下婴儿的气管短,平均长度仅5.7cm ; 6. 小儿扁桃体和腺样体在4~6岁时达最大形状; 7. 头大,颈短; 8. 氧耗增加和氧储蓄低; 9. 面罩通气容易胃扩张,易反流误吸、FRC 、肺顺应性易下降; 10.心动过缓是对缺氧的主要反应,心率是心排出量的主要决定因素;随着麻醉的加深,维持上呼吸道开放的肌肉逐渐松弛,咽气道易塌陷,导致上呼吸道梗阻; 11.小儿呼吸道开放活动的调节。 二. 面罩通气 1. 选择适合于小儿面部形状、死腔量最小的面罩 透明面罩:最常用,小儿不易惊恐,可观察患儿口鼻部情况; Rendell-Baker 面罩:形状符合小儿的面部轮廓,无效腔量较小,但没有充气密闭圈;

Laerdal 面罩:质地柔软的硅橡胶面罩,密闭性较好,能进行煮沸和高压蒸气消毒。 2. 面罩通气的操作要点: ① 正确放置面罩: ② 手法: 3. 面罩通气时的监测 — 监测呼吸音或呼吸运动 — 监测P ET CO 2波形 — 监测呼吸囊的运动 4. 口咽通气道的使用: — 小儿常选用Guedel 和Berman 口咽通气道。

注意点: 在插入口咽通气道前应达满意的麻醉深度; 选择合适的口咽通气道,长度大约相当于从门齿至下颌角的长度。 三. 气管内插管 1. 插管前器械和物品准备 气管插管基本器械的准备 预氧和通气器械 1. 麻醉机或通气装置的准备 2. 准备小、中、大号面罩 3. 准备小、中、大号口咽和鼻咽通气道 气管导管及相关物品 4. 准备小、中、大三根经口插入的气管导管 5. 准备柔韧的插管芯(大小各一) 6. 准备润滑剂(最好含局麻药) 7. 喷雾器(含局麻药) 8. 准备注气注射器 喉镜操作相关设备 9. 打开吸引器,并连续硬质 10. 插管钳 11. 光源正常的1#、2#、3#Miller喉镜片,新生儿应准备直喉镜片 12. 置病人头部呈“嗅物位”的枕头或薄垫 固定气管导管所需的物品 13. 胶布(布质或丝质为好,不用纸质)或固定带 14. 牙垫(大、小) 确定气管导管位置所需的器械 15. 听诊器 16. P ET CO2监测仪 17. 脉搏氧饱和度仪 2. 喉镜检查 ①保持头的正确位置:6岁以下小儿头置于水平位,以头圈固定,由于这种年龄组小儿喉头位置高,如有必要可在环状软骨上加压,以更好地暴露声门。 6岁以上小儿,头置于小枕头上轻度屈曲颈椎,可改善插管角度和更好地显示声门。 ②仔细检查牙齿:因许多儿童开始更换乳牙,在喉镜检查必须注意,在插管时用大拇指推开嘴唇,对牙齿不施加任何压力。术前如发现有明显松动的牙齿,需向其家长说明拔掉

麻醉三基考试6-小儿麻醉 姓名: 选择题 (A1~A2型题) 1、下列对小儿呼吸道的描述,不正确的是() A.婴儿舌头相对较大,使得婴儿发生呼吸道梗阻的机会较高 B.咽喉属于喉部较高的位置,因此气管插管时,较常用直喉镜片而非弯的喉镜片 C.会厌的形状与成人不同,使得以喉镜进行插管较困难 D.8岁儿童,其喉的最狭窄部位是环状软骨水平 E.婴儿气管长度是4.0~4.3cm 2、下列对小儿循环系统的描述,不正确的是() A.心排量依靠增加心率来代偿 B.6个月以下的婴儿如心率低于100次/分,应注意有无缺氧,迷走反射或麻醉过深 C.在同等深度麻醉下,新生儿压力反射较成人更易受到抑制 D.小儿血容量绝对值较成人小,但按千克体重计算并无差异 E.新生儿的心脏很难接受容量和压力的急剧变化 3、关于新生儿麻醉下列何项正确() A.中枢神经系统发育不完善,手术时没有必要采取完善的镇痛措施 B.体温调节机制已发育完善 C.新生儿麻醉中易发生低体温 D.由于细胞外液占体重的比例较成人大,对禁食及体液限制耐受性好

E.肾小球滤过率与成人相仿,不影响药物代谢 4、小儿药理学特点的叙述中,不正确的是() A.新生儿按体重给药常需较大剂量 B.新生儿肾小球滤过率低,可涌向药物排泄 C.新生儿吸入麻醉药MAC较儿童低 D.2~3个月婴儿吸入麻醉药MAC较成人高 E.新生儿肝微粒体酶系统发育已完全,药物半衰期并不延长 5、婴幼喉头最狭窄的部位是() A.声门裂处 B.咽喉部 C.环状软骨水平 D.甲状软骨水平 E.前庭裂 6、婴儿气管长度是() A.1.0~2.5cm B.2.0~3.2cm C.3.0~4.0cm D.4.0~4.3cm E.4.9~5.0cm 7、婴儿气管支气管分叉处在() A.T1 B.T2 C.T3 D.T4 E.T5 8、对于小儿麻醉前评估,不正确的是() A.特别注意近期有无上呼吸道感染病史 B.先天性疾病往往合并其它系统的异常

小儿麻醉气道和呼吸管理指南 中华医学会麻醉学分会儿科麻醉学组 一、目的 随着医疗技术及仪器设备的发展与进步,麻醉相关并发症与死亡率已明显降低。然而,在已报道的与麻醉相关的并发症中,新生儿和婴幼儿、急诊手术以及合并呼吸问题(气道梗阻、意外拔管、困难插管)等仍是高危因素。气道和呼吸管理仍是小儿麻醉主要出现并发症和死亡的主要因素。管理好围术期小儿气道和呼吸非常重要。小儿麻醉科医师必须了解与熟悉小儿的解剖生理特点,并根据不同年龄选用合适的器械设备,采取相应的管理措施,才能确保患儿手术麻醉的安全。 二、小儿气道的解剖和生理特点 (一)解剖特点 1、头、颈:婴幼儿头大颈短,颈部肌肉发育不全,易发生上呼吸道梗阻,即使施行椎管内麻醉,若体位不当也可阻塞呼吸道。

2、鼻:鼻孔较狭窄,是6个月内小儿的主要呼吸通道,且易被分泌物、粘膜水肿、血液或者不适宜的面罩所阻塞,出现上呼吸道梗阻。 3、舌、咽:口小舌大,咽部相对狭小及垂直,易患增殖体肥大和扁桃体炎。 4、喉:新生儿、婴儿喉头位置较高,声门位于颈3~4平面,气管插管时可压喉头以便暴露喉部。婴儿会厌长而硬,呈“U”型,且向前移位,挡住视线,造成声门显露困难,通常用直喉镜片将会厌挑起易暴露声门。由于小儿喉腔狭小呈漏斗形(最狭窄的部位在环状软骨水平,即声门下区),软骨柔软,声带及粘膜柔嫩,易发生喉水肿。当导管通过声门遇有阻力时,不能过度用力,而应改用细一号导管,以免损伤气管,导致气道狭窄。 5、气管:新生儿总气管长度约4~5cm,内径4~5mm,气管长度随身高增加而增长。气管分叉位置较高,新生儿位于3~4胸椎(成人在第5胸椎下缘)。3岁以下小儿双侧主支气管与气管的成

小儿麻醉的气道管理

小儿麻醉的气道管理 温州医学院附二院连庆泉 一. 小儿呼吸道的解剖生理学特点 1. 鼻孔小,是6个月内的主要呼吸通道; 2. 舌相对大,喉相对小,位置高; 3. 会厌短,常呈Ω形或U形; 4. 环状软骨是小儿喉的最狭窄处; 5. 3个月以下婴儿的气管短,平均长度仅5.7cm; 6. 小儿扁桃体和腺样体在4~6岁时达最大形状; 7. 头大,颈短; 8. 氧耗增加和氧储蓄低; 9. 面罩通气容易胃扩张,易反流误吸、FRC、肺顺应性易下降; 10.心动过缓是对缺氧的主要反应,心率是心排出量的主要决定因素;随着麻醉的加深,维持上呼吸道开放的肌肉逐渐松弛,咽气道易塌陷,导致上呼吸道梗阻; 11.小儿呼吸道开放活动的调节。

二. 面罩通气 1. 选择适合于小儿面部形状、死腔量最小的面罩 透明面罩:最常用,小儿不易惊恐,可观察患儿口鼻部情况; Rendell-Baker面罩:形状符合小儿的面部轮廓,无效腔量较小,但没有充气密闭圈; Laerdal面罩:质地柔软的硅橡胶面罩,密闭性较好,能进行煮沸和高压蒸气消毒。 2. 面罩通气的操作要点: ①正确放置面罩:

②手法: 3. 面罩通气时的监测 —监测呼吸音或呼吸运动 —监测P ET CO2波形 —监测呼吸囊的运动 4. 口咽通气道的使用: —小儿常选用 Guedel和Berman口咽通气道。 注意点: 在插入口咽通气道前应达满意的麻醉深度; 选择合适的口咽通气道,长度大约相当于从门齿至下颌角的长度。

三. 气管内插管 1. 插管前器械和物品准备 气管插管基本器械的准备 预氧和通气器械 1. 麻醉机或通气装置的准备 2. 准备小、中、大号面罩 3. 准备小、中、大号口咽和鼻咽通气道 气管导管及相关物品 4. 准备小、中、大三根经口插入的气管导管 5. 准备柔韧的插管芯(大小各一) 6. 准备润滑剂(最好含局麻药) 7. 喷雾器(含局麻药) 8. 准备注气注射器 喉镜操作相关设备 9. 打开吸引器,并连续硬质 10. 插管钳 11. 光源正常的1#、2#、3#Miller喉镜片,新生儿应准备直喉镜片 12. 置病人头部呈“嗅物位”的枕头或薄垫 固定气管导管所需的物品 13. 胶布(布质或丝质为好,不用纸质)或固定带 14. 牙垫(大、小) 确定气管导管位置所需的器械 15. 听诊器 16. P ET CO2监测仪 17. 脉搏氧饱和度仪 2. 喉镜检查 ①保持头的正确位置:6岁以下小儿头置于水平位,以头圈固定,由于这种年龄组小儿喉头位置高,如有必要可在环状软骨上加压,以更好地暴露声门。

小儿麻醉气道和呼吸管理指南(全文) 中华医学会麻醉学分会 目录 一、目的 二、小儿气道解剖特点 三、气道器具及使用方法 四、通气装置及通气模式 五、小儿困难气道处理原则和方法 一、目的 在已报道的麻醉相关并发症中,新生儿和婴幼儿、急诊手术以及合并呼吸问题(气道上梗阻、意外拔管、困难插管)等仍是高危因素。气道和呼吸管理仍是小儿麻醉主要出现并发症和死亡的主要因素。小儿麻醉科医师必须了解与熟悉小儿的解剖生理特点,并根据不同年龄选用合适的器械设备,采取相应的管理措施,才能确保患儿手术麻醉的安全。 二、小儿气道的解剖和生理特点 1、头、颈婴幼儿头大颈短,颈部肌肉发育不全,易发生上呼吸道梗阻,即使施行椎管内麻醉,若体位不当也可引发呼吸道阻塞。

2、鼻鼻孔较狭窄,是6个月内小儿的主要呼吸通道,分泌物、黏膜水肿、血液或者不适宜的面罩导致鼻道阻塞,出现上呼吸道梗阻。 3、舌、咽口小舌大,咽部相对狭小及垂直,易患增殖体肥大和扁桃体炎。 4、喉新生儿、婴儿喉头位置较高,声门位于颈3~4平面,气管插管时可压喉头以便暴露喉部。婴儿会厌长而硬,呈"U"型,且向前移位,挡住视线,造成声门显露困难,通常用直喉镜片将会厌挑起易暴露声门。由于小儿喉腔狭小呈漏斗形(最狭窄的部位在环状软骨水平,即声门下区),软骨柔软,声带及黏膜柔嫩,易发生喉水肿。当导管通过声门遇有阻力时,不能过度用力,而应改用细一号导管,以免损伤气管,导致气道狭窄。 5、气管新生儿总气管长度约 4~5cm,内径 4~5mm,气管长度随身高增加而增长。气管分叉位置较高,新生儿位于 3~4 胸椎(成人在第 5 胸椎下缘)。 3 岁以下小儿双侧主支气管与气管的成角基本相等,与成人相比,行气管内插管导管插入过深或异物进入时,进入左或右侧主支气管的几率接近。 6、肺小儿肺组织发育尚未完善,新生儿肺泡数只相当于成人的8%,单位体重的肺泡表面积为成人的 1/3,但其代谢率约为成人的两倍,因此新生儿呼吸储备有限。肺间质发育良好,血管组织丰富毛细血管与淋巴组织间隙较成人为宽,造成含气量少而含血多,故易于感染,炎症也易蔓延,易引起间质性炎症,肺不张及肺炎。由于弹力组织发育较差,肺膨